Abstract

Data deriving from randomized clinical trials, observational studies and meta-analyses, including treatment regimens unlicensed for use in clinical practice, clearly support that 150 mg once-monthly oral and 3 mg quarterly i.v. doses of ibandronate are associated with efficacy, safety and tolerability; notably both these marketed regimens, which largely correspond to ACE ≥10.8 mg, may in addition provide a significant efficacy on non-vertebral and clinical fracture (Fx) efficacy. The MOBILE and the DIVA LTE studies confirmed a sustained efficacy of monthly oral and quarterly i.v. regimens respectively, over 5 years. Furthermore, improved adherence rates with monthly ibandronate, deriving from studies evaluating large prescription databases, promise to enhance fracture protection and decrease the social and economic burden of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Keywords: ibandronate, bisphosphonates, osteoporosis, long-term efficacy, fracture.

Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (BPs) are standard first-line pharmacotheraphy for osteoporosis (OP), along with calcium and vitamin D supplementation, physical training and fall prevention (1-4).

BPs such as alendronate (ALN), ibandronate (IBN), risedronate (RIS) and zoledronate (ZOL), have demonstrated antifracture efficacy and represent the most widely used agents, all approved in Europe and in the USA for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO); however, in clinical practice <20% of patients receive appropriate treatments. Even when BPs are prescribed, their therapeutic benefit, also including their antifracture efficacy, may be compromised in the real world by suboptimal treatment compliance and/or failure to persist with the treatment prescribed (5-11). It is anticipated that reducing dosing frequency may improve therapeutic adherence, so that new drugs or treatment regimens that reduce the risk for osteoporotic fractures (Fx) and make the treatment of OP more convenient and suitable for patients are needed (5, 11, 12).

IBN is a nitrogen-containing BP, more potent than ALN and RIS, with enhanced affinity for bone, which is greater than that of clodronate or RIS (13, 14); its increased antiresorptive potency, together with an extended persistence in skeletal tissue, allows oral and also intravenously administration, with variable dosing intervals, even longer than 2 months (13).

The antifracture efficacy of daily oral IBN (2.5 mg) and intermittent oral IBN (20 mg every other day for 12 doses every 3 months) was assessed in a 3-year randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial (RCT), evaluating 2946 women with PMO and at least 1 prevalent Fx in the pivotal BONE study (iBandronate Osteoporosis trial in North America and Europe) (15). The two IBN regimens were associated with significant reductions in the risk of vertebral Fx vs placebo (62%, p= 0.0001, and 50%, p= 0.0006, respectively); a significant reduction in non-vertebral Fx was not seen in the overall population (mean total hip BMD T-score = -1.7). However, subgroup analyses including women at higher risk for Fx showed significant reductions in non-vertebral Fx risk (femoral neck BMD T-score < -3.0: 69%, p= 0.012; lumbar spine BMD T-score < -2.5 and a history of clinical Fx in the past 5 years: 62%: p = 0.025) (15). A post hoc analysis of the BONE trial indicated that oral IBN 2.5 mg daily significantly reduces the risk of vertebral Fx of greater severity, reporting at 1 year a reduction of 59% in the RR of combined new moderate and severe vertebral Fx (p= 0.0164) (16).

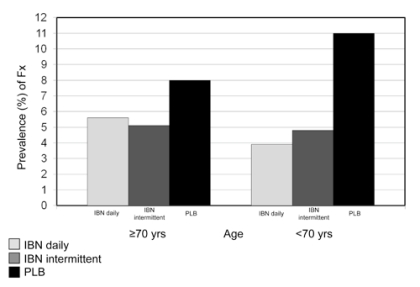

The efficacy of daily and intermittent IBN in reducing the incidence of new morphometric vertebral Fx was also evaluated in a predefined subgroup of women aged ≥ 70 and <70 years of the BONE study (Figure 1) (17). The result showed no statistically significant differences in Fx rates between the two age-groups, confirming that the efficacy of IBN was not influenced by age.

Figure 1.

- The BONE Study. Rates of new morphometric vertebral Fx in age groups ≥ 70 and < 70 according to different IBN regimens (17).

The BONE trial was the first to have reported comparable vertebral antifracture efficacy of daily and intermittent administration (with a dose-free interval of >2 months) of a BP, suggesting that IBN could be administered at intervals longer than daily or weekly.

Therefore, following the demonstration of antifracture efficacy with daily IBN, the focus became that of extending the dose-free interval to develop a more convenient regimen. As identified in an extensive modelling and simulation project, 50 + 50 mg (single doses on consecutive days), 100 and 150 mg doses of monthly IBN and daily 2.5 mg were evaluated in the Monthly Oral iBandronate In LadiEs (MOBILE) study, a 2-year, randomized, double blind, phase III, non inferiority trial (18, 19). The 150 mg dose produced the greatest gains in BMD vs daily IBN (2.5 mg) at 2 years (lumbar spine BMD: 6.6 vs 5.0%, respectively, p< 0.001) (19). All regimens reduced serum CTX (a marker of bone resorption) to within the premenopausal range by 3 months and maintained the lower levels throughout the 2-year study; the incidence of clinical Fx, reported as adverse events, was similarly low across the treatment groups. Long-term efficacy of both monthly regimens (100 and 150 mg) has been evaluated in the 3-year (5 years of treatment) extension study (MOBILE LTE) (20). The results showed that in patients receiving 5 years of continuous monthly IBN (100 or 150 mg), lumbar spine BMD increased by 8.2% and 8.4%, respectively, compared with baseline (Figure 2); a continuous BMD increase was also documented at all hip sites, although at a lesser extent (20). The reduced levels of serum CTX reported during the 2-year MOBILE study, have been maintained throughout the 3 years of the LTE (Figure 3) (20).

Figure 2.

- The MOBILE LTE Study. Lumbar spine BMD changes over 5 years (18-20). ITT population. Pooled data; subgroup of patients treated continuously with the same dose of IBN for 5 years.

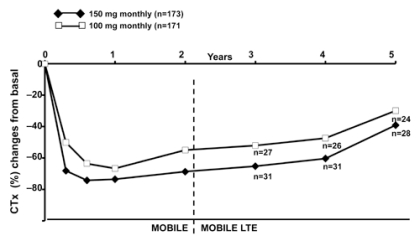

Figure 3.

- The MOBILE LTE Study. Serum CTX changes over 5 years (18-20). ITT population. Pooled data; subgroup of patients treated continuously with the same dose of IBN for 5 years.

Because IBN can also be administered by i.v. injections (given over 15-30 seconds), with extended dose-free intervals, the Dosing Intravenous Administration (DIVA) study (21) was planned to identify the optimal i.v. dosing regimen with the antifracture efficacy and safety profile similar to that of 2.5 mg orally daily. The DIVA study compared the efficacy of two regimens of intermittent i.v. injections of IBN (2 mg every 2 months and 3 mg quarterly) with a regimen of daily oral IBN (2.5 mg), the latter of which has proven antifracture efficacy. The design of DIVA was the same as MOBILE, with the exception of the different route of IBN administration. At 2 years, the 2- and 3-monthly i.v. regimens produced improvements in spinal BMD (6.4% and 6.3%, respectively) that were superior to oral IBN (4.8%; p<0.001) (22). BMD gains at all hip sites were also greater in the i.v. groups than in the oral group; serum CTX levels were markedly reduced in all treatment groups. The incidence of clinical Fx after 2 years, reported as adverse events, was similar in groups receiving i.v. and slightly, but not significantly, lower than in the daily oral group (22). As with the oral IBN MOBILE study, a 3-year (5 years of treatment) LTE of DIVA was conducted (23). In the DIVA LTE, patients received IBN i.v. injections 2 mg every 2 months and 3 mg quarterly only. Therefore, patients previously receiving 2 mg 2-monthly or 3 mg quarterly i.v. IBN injections in the 2-year DIVA study, continued to receive the same treatment in the LTE for additional 3 years; patients receiving oral IBN in DIVA were switched to i.v. IBN, according to the i.v. placebo regimen received during 2-year DIVA. In patients receiving 5 years of continuous 2 mg 2-monthly or 3 mg quarterly i.v. IBN injections, lumbar spine BMD increased by 8.4% and 8.1%, respectively, compared with DIVA baseline (pooled analysis) (Figure 4). A continuous BMD increase was also documented at all hip sites, although at a lesser extent. Both the MOBILE and the DIVA LTE studies clearly confirmed dose-related increases of BMD in all measured sites.

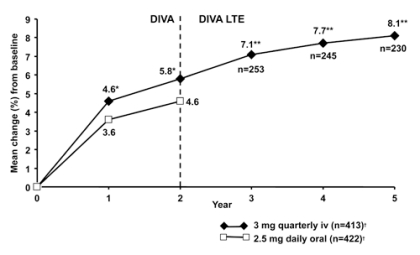

Figure 4.

- The DIVA LTE Study. Lumbar spine BMD changes over 5 years in patients treated with IBN 3 mg quarterly i.v. (21-23). ITT analysis; *p<0.001 vs IBN daily 2.5 mg; **95% CI; †At 2 years.

Two meta-analyses to assess the antifracture efficacy of different doses of IBN have recently been completed using slightly different methodologies. The first meta-analysis used individual patient data from MOBILE and DIVA trials of similar design, to assess the effect of different doses of IBN on non-vertebral Fx (24). The varying doses used in the two studies were grouped on the basis of annual cumulative exposure (ACE = dose x dose frequency/year x absorption factor e.g., 150 mg x 12 x 0.006 = 10.8 mg). This analysis showed a relative risk reduction in non-vertebral Fx rate of 38% when comparing combined doses (including monthly oral IBN 150 mg, quarterly i.v. IBN 3 mg and i.v. IBN 2 mg every 2 months) equivalent to ACE ≥10.8 mg with ACE of 5.5 mg (2.5 mg daily). Notably, a dose-response effect was noted with increasing ACE (7.2-12 mg) compared with ACE of 5.5 mg.

The second meta-analysis (25) used individual patient data from four pivotal Phase III clinical trials [i.v. Fx prevention study (26), BONE, MOBILE, and DIVA]. BONE and the i.v. Fx prevention study were 3-year placebo-controlled Fx trials; MOBILE and DIVA were 2-year BMD active-comparator studies, which collected Fx data as safety measurements. Similar to the Canadian analysis (24), annual doses were grouped by ACE: high (≥10.8 mg includes 150 mg oral monthly, 3 mg i.v. quarterly and 2 mg i.v. every 2 months), mid (5.5 - 7.2 mg) and low (≤ 4.0 mg). However, rather than comparing with the low IBN dose group, this analysis compared reductions in Fx risk with placebo, using a combined placebo group from BONE and the i.v. Fx prevention study. It was observed that the risk of clinical (vertebral and non-vertebral) and non-vertebral Fx was significantly reduced for doses of IBN with ACE ≥10.8 mg compared with placebo. A significant reduction in risk associated with IBN was also demonstrated for a subgroup of six major non-vertebral Fx (clavicle, humerus, wrist, pelvis, hip and leg).

A further meta-analysis (27) pooled data from the four Phase III clinical trials of IBN to assess the relationship between IBN dose, changes in BMD, and rates of both clinical and non-vertebral Fx. Individual patient data from four phase III clinical trials of IBN (i.v. Fx prevention study, BONE, MOBILE, and DIVA) were pooled and analyzed. Oral doses included 2.5 mg daily, 20 mg intermittent, 100 mg monthly, 2×50 mg monthly, and 150 mg monthly dose. IV doses included 0.5 mg quarterly, 1 mg quarterly, 2 mg every 2 months, and 3 mg quarterly dose. A total of 8710 patients were included in this analysis. Both lumbar spine and total hip BMD were observed to increase with increasing IBN dose; the incidence of all clinical Fx was observed to decrease as lumbar spine BMD increased. A statistically significant inverse linear relationship was observed between percent change in lumbar spine BMD and the rate of clinical Fx (p=0.005). A non-significant curvilinear relationship was observed between percent change in total hip BMD and non-vertebral Fx rate.

The findings of these meta-analyses all support that treatment with higher IBN doses was associated with larger gains in BMD, and larger gains in lumbar spine BMD were correlated with lower risk of all clinical Fx (24, 25, 27).

No prospective head-to-head trials comparing the antifracture efficacy of BPs have been conducted, and direct efficacy comparisons between BPs in randomized trials have only used surrogate efficacy markers such as BMD and markers of bone turnover, owing to the large sample size such studies would require in order to detect differences in Fx risk.

MOTION (Monthly Oral Therapy with Ibandronate for Osteoporosis iNtervention) is the first head-to-head study (28) comparing clinical outcomes of once-monthly IBN 150 mg and once-weekly ALN 70 mg. After 12 months, increases in BMD from baseline were similar in both treatment groups, as were vertebral Fx incidences (0.6% in both groups). The incidences of non-vertebral Fx with ALN and IBN were 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.

Although RCTs are considered the gold standard in clinical research, the clinical relevance of the data is limited by the strict selection of study participants and by the tightly controlled design, which is difficult to apply in the real world. Even the high level of treatment adherence seen in RCTs is often not reproduced in actual patients setting and could negatively influence the efficacy outcomes. Therefore, a better understanding of the benefits of a treatment can be provided by complementary observational database analyses on large cohorts of unselected patients, thus allowing direct insights into day-to-day clinical practice (29, 30).

The eValuation of IBandronate Efficacy (VIBE) study compared Fx rates between patients newly treated with monthly IBN and weekly oral ALN or RIS (31). The primary analysis population included 7.345 monthly-IBN and 56,837 weekly-ALN or –RIS patients, who were adherent to treatment during the first 90 days after the index date. After the 12-month observational period, Fx risk was similar between patients receiving monthly IBN or weekly BPs for hip, non-vertebral or any clinical Fx. IBN patients had a 64% lower risk of vertebral Fx than weekly-BPs patients (p= 0.006). In the intent-to-treat analysis, which included all patients who received at least one BP prescription, RRs for Fx were not significantly different between treatment groups for all Fx types.

The new treatment regimens of IBN, characterized by extended between-dose intervals, may enhance treatment adherence (compliance and/or persistence), which still remains suboptimal with once-weekly regimens (5, 8, 9, 11). Data deriving from longitudinal and retrospective analyses of pharmacy claims data comparing monthly IBN with weekly BPs (32-35) support evidence that patients prefer a further reduced dosing frequency of once-monthly IBN to a weekly regimen. This enhanced adherence to BP therapy, even in patients who previously discontinued daily or weekly treatment due to GI intolerability (36).

In terms of bone quality and strength, two recent studies have assessed these aspects in patients treated with once-monthly oral IBN (37) and in patients who had received the drug i.v. (38).

The first was a RCT that evaluated in women with PMO the effects of once-monthly oral IBN (150 mg) on the hip and lumbar spine BMD by DXA and QCT and by two novel analytical methods: FEA (finite element analysis) of QCT data and HSA (hip structural analysis) of DXA. FEA, which calculates bone strength from QCT data, strongly predicts in vitro femoral and vertebral breaking strength and can reveal when treatment increases strength beyond its BMD effect (39). HAS reconstructs femoral bone strength from DXA data and can reveal geometrical contributions to Fx risk not captured by DXA (40). The results of this study showed that once-monthly oral IBN for 12 months improved hip and spine BMD measured by QCT and DXA and strength estimated by FEA of QCT scans.

In the second study (38) single transiliac bone biopsy was performed in a subgroup (N=109) of patients from DIVA study, treated with i.v. IBN 2 mg every 2 months, 3 mg every 3 months or oral IBN 2.5 mg daily, plus oral or i.v. placebo. Following 2 years of oral or i.v. IBN treatment, histomorphometric analysis of transiliac bone biopsies demonstrated normal micro-structure of newly formed bone with normal mineralization and reduced remodeling.

In conclusion, in reviewing data deriving from RCTs, observational studies and meta-analyses, including treatment regimens unlicensed for use in clinical practice, the evidence clearly supports that 150 mg once-monthly oral and 3 mg quarterly i.v. doses of IBN are associated with efficacy, safety and tolerability; notably, both these marketed regimens, which largely correspond to ACE ≥10.8 mg, may in addition provide a significant efficacy on non-vertebral and clinical Fx. Data deriving from the MOBILE and the DIVA LTE studies confirmed a sustained efficacy of monthly oral and quarterly i.v. regimens respectively, over 5 years. Furthermore, improved adherence rates with monthly IBN, deriving from studies evaluating large prescription databases, promise to enhance Fx protection and decrease the social and economic burden of PMO.

References

- 1.Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:399–428. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0560-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller PD. Anti-resorptives in the management of osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:849–68. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geusens PP, Roux CH, Reid DM, et al. Drug Insight: choosing a drug treatment strategy for women with osteoporosis-an evidence—based clinical perspective. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:240–8. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonen S, Kay R, Cooper C, et al. Osteoporosis management: a perspective based on bisphosphonate data from randomised clinical trials and observational databases. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1792–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–60. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebaldt OI, Shane LG, Pham B, et al. Longer term effectiveness outcomes of noncompliance and nonpersistence with daily regimen bisphosphonates therapy in patients with osteoporosis treated in tertiary specialist care. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(1):S107. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:1003–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Aug;81(8):1013–22. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgström F, Herings RM, Silverman SL. Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med. 2009;122(2 Suppl):S3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reginster JY, Rabenda V. Patient preference in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis with bisphosphonates. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1:415–23. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O, et al. Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:914–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:856–61. doi: 10.4065/80.7.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papapoulos SE. Ibandronate: a potent new bisphosphonate in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nancollas GH, Tang R, Phipps RJ, et al. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone. 2006;38:617–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesnut III CH, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241–9. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenberg D, Miller P, Armbrecht G, Wilson K, Schimmer RC, Papapoulos SE. Oral ibandronate significantly reduces the risk of vertebral fractures of greater severity after 1, 2, and 3 years in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Bone. 2005;37:651–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ettinger MP, Felsenberg D, Harris ST, et al. Safety and tolerability of oral daily and intermittent ibandronate are not influenced by age. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1968–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller PD, McClung MR, Macovei L, et al. Monthly oral ibandronate therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results from the MOBILE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1315–22. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reginster JY, Adami S, Lakatos P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of once-monthly oral ibandronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2 year results from the MOBILE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:654–61. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenberg D, Czerwinski E, Stakkestad J, Neate C, Masanauskaite D, Reginster JY. Efficacy of monthly oral Ibandronate is maintained over 5 years: the MOBILE LTE study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(1):S5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delmas PD, Adami S, Strugala C, et al. Intravenous ibandronate injections in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: one-year results from the dosing intravenous administration study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1838–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisman JA, Civitelli R, Adami S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of intravenous ibandronate injections in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2-year results from the DIVA study. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:488–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bianchi G, Felsenberg D, Czerwinski E. Efficacy of i.v. Ibandronate is maintained over 5 years: the DIVA LTE study . Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(3):494. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cranney A, Wells GA, Yetisir E, et al. Ibandronate for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:291–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris ST, Blumentals WA, Miller PD. Ibandronate and the risk of non-vertebral and clinical fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: results of a meta-analysis of phase III studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:237–45. doi: 10.1185/030079908x253717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recker R, Stakkestad JA, Chesnut CH 3rd, et al. Insufficiently dosed intravenous ibandronate injections are associated with suboptimal antifracture efficacy in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2004;34:890–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sebba AI, Emkey RD, Kohles JD, Sambrook PN. Ibandronate dose response is associated with increases in bone mineral density and reductions in clinical fractures: results of a meta-analysis. Bone. 2009;44:423–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller PD, Epstein S, Sedarati F, Reginster JY. Once-monthly oral ibandronate compared with weekly oral alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from the head-to-head MOTION study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:207–13. doi: 10.1185/030079908x253889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman SL, Watts NB, Delmas PD, Lange JL, Lindsay R. Effectiveness of bisphosphonates on nonvertebral and hip fractures in the first year of therapy: the risedronate and alendronate (REAL) cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0274-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Saag KG, Delzell E. RisedronatE and ALendronate Intervention over Three Years (REALITY): minimal differences in fracture risk reduction. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:973–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0772-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris ST, Reginster JY, Harley C, et al. Risk of fracture in women treated with monthly oral ibandronate or weekly bisphosphonates: the eValuation of IBandronate Efficacy (VIBE) database fracture study. Bone. 2009;44:758–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman SL, Cramer JA, Sunyec Z, et al. Women are more persistent with monthly bisphosphonates therapy compared to weekly bisphosphonates: 12-Month results from 2 retrospective databases. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(1):S454. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emkey R, Koltun W, Beusterien K, et al. Patient preference for once-monthly ibandronate versus once-weekly alendronato in a randomized, open-label, cross-over trial: the Boniva Alendronate Trial in Osteoporosis (BALTO) Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1895–903. doi: 10.1185/030079905X74862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper A, Drake J, Brankin E. PERSIST Investigators. Treatment persistence with once-monthly ibandronate and patient support vs. once-weekly alendronate: results from the PERSIST study. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotté FE, Fardellone P, Mercier F, Gaudin AF, Roux C. Adherence to monthly and weekly oral bisphosphonates in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(1):145–55. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0930-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewiecki EM, Babbitt AM, Piziak VK, Ozturk ZE, Bone HG. Adherence to and gastrointestinal tolerability of monthly oral or quarterly intravenous ibandronate therapy in women with previous intolerance to oral bisphosphonates: a 12-month, open-label, prospective evaluation. Clin Ther. 2008;30(4):605–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewiecki EM, Keaveny TM, Kopperdahl DL, et al. Once-monthly oral ibandronate improves biomechanical determinants of bone strength in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:171–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Recker RR, Ste-Marie LG, Langdahl B, et al. Effects of intermittent intravenous ibandronate injections on bone quality and micro-architecture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: The DIVA study. Bone. 2009 Nov 10; doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.11.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez CJ, Keaveny TM. A biomechanical perspective on bone quality. Bone. 2006;39:1173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonnick SL. HSA: beyond BMD with DXA. Bone. 2007;41(1) 1:S9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]