Abstract

The bone surrounding a prosthetic implant normally experiences a progressive quantitative reduction as a result of stress shielding and wear debris production, that can lead to the aseptic loosening of the implant. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), using software algorithms, can ensure a surrogate measure of load redistribution after the implant of the prosthetic components and can be a valid tool to evaluate the efficacy of pharmacological therapy to reduce the periprosthetic bone loss. In several animal and human studies DXA has been able to quantify antiresorptive action of bisphosphonates in the periprosthetic area.

Keywords: DXA, periprosthetic bone loss, pharmacological treatment.

Introduction

Hip and knee arthroplasties are common procedures for the treatment of degenerative disease of these joints. They are successful orthopaedic surgical interventions with an optimal cost-effectiveness rate, although no prosthesis has an unlimited duration and often does not even cover the patient’s life expectancy. The life of the prosthetic implants has increased over time, nowadays the survival time is over 15 years for the 80%-95% of the implanted hip arthroplasties (1).

The implantation of foreign materials in the human body generates a series of modifications and adaptations in the host tissue. The type and extent of these modifications depend on different factors: biocompatibility of the material, interference with the biomechanical characteristics of the host tissue, wear and wear debris rate of the components of the implanted material, state of the host tissue, local and general reactivity. Therefore the bone surrounding a prosthetic implant normally experiences a progressive quantitative reduction (bone loss) as a result of two main factors: stress shielding and wear debris production (2, 3).

Stress shielding involves the physical phenomenon of subtraction of a part of the bone from the physiological load and thus the mechanical strains which determine a normal remodeling. This is due to the different stiffness of the implanted material compared to the surrounding bone. This phenomenon occurs most frequently with femoral stems of a greater size and rigidity, and normally involves the proximal third or half of the femur. In cemented implants, the cement creates a better distribution of the stresses and as such the phenomenon is less relevant. The periprosthetic bone responds to these modifications of the mechanical stress with an adaptive bone remodeling, thus leading, in case of hip arthroprosthesis, to a relevant bone resorption at the calcar and trochanter regions, and with a neoapposition in the distal diaphyseal region (4).

Recently it has been postulated that the pathogenesis of bone resorption related to stress shielding is due to the activity of osteocytes. These cells are interconnected with each other and with osteoblasts and lining cells via dendritic processes forming a communication network throughout the bone matrix and the bone surface. It has been hypothesized that osteocytes mediate bone adaptation to mechanical strain. This theory is supported by recent evidences demonstrating that ablation of osteocytes result in lack of responsiveness of the skeleton to strain (5). Sclerostin, produced by osteocytes, is a molecule that stimulates osteoblasts to produce the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANK-L) leading to an increase of osteoclastic activity. Sclerostin expression decreases following mechanical strain (bone anabolic process) (6), while it increases in unloading conditions (6, 7). This suggests that sclerostin suppression might be required to enable local bone-forming responses to mechanical strain. Blocking sclerostin action could be promising to prevent bone loss related to stress shielding phenomena.

Osteolysis, induced by the presence of wear debris, leads to the aseptic loosening of the implant (8). Particulate debris originates from the attrition of the prosthetic surfaces. This debris is normally made up of particles of polyethylene which are the principal components of the acetabular cup (9, 10). Wear debris causes a flogistic response with the production of mediators of the inflammation and cytokines, with activation of the RANK/RANK-L axis, which is indicated by expression of RANK, RANK-L, and osteoprotegerin (OPG) in periprosthetic membranes (11, 12).

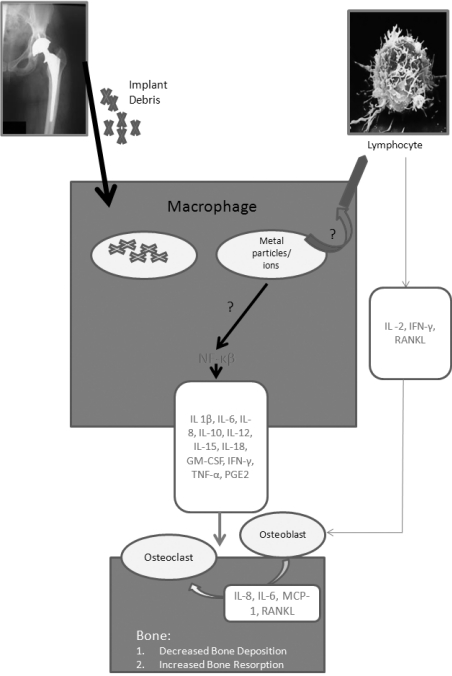

This activation culminates in an enhanced osteoclast recruitment and activity adjacent to bone-implant interfaces, leading to osteolysis and loosening of the implant. The presence of particles is not in itself sufficient to justify the foreign body reaction. This will, in fact, occur when there is enough mobility of the prosthetic implant to increase the “effective articular space”, enabling the migration of the particles in the bone-prosthesis interface, with a pump mechanism, determined by the pressure cycles induced by movement during joint motion (13). Periprosthetic osteolysis is thus the result of the combined action of an increase in bone resorption, stimulated directly by the particles or through a process of inflammation, associated to reduced bone neoformation caused by a depression of the osteoblastic activity as a result of the toxicity of the debris (14) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

- Macrophage as the pivotal cell of wear debris induced inflammation.

Measure of the bone response to implant

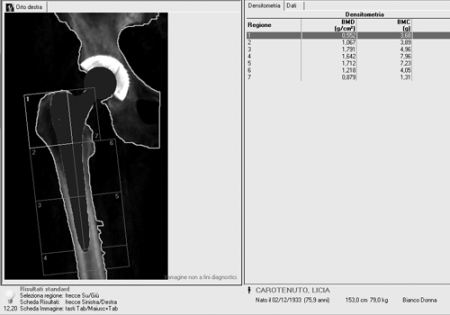

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) can ensure a surrogate measure of load redistribution after the implant of the prosthetic components. Traditionally, bone resorption has been assessed by visual interpretation of radiographs; however, quantitative studies employing X-ray densitometry have demonstrated that changes in density as large as 20% can be due to differences in film response, exposure variations, and positional inaccuracies. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was developed to measure the bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, the femoral neck and the total body, with a minimal radiation exposure for the patients. The technique has been extended to the measurement of periprosthetic bone density using software algorithms for the detection of the bone around the implant. With this technique it is possible to have information about BMD measured in the seven Gruen zones (Figure 2). The reproducibility of the measurements (coefficients of variation) is in the range 1.8 to 7.5%. Measurement of bone mineral density is an indirect index of distribution of mechanical burden, induced by a particular prosthetic design, and of consequent bone biological response. DXA can easily adapt its periprosthetic analysis algorithm to the specific requirements of new implant designs (15).

Figure 2.

- Seven Gruen zones in DXA periprosthetic evaluation.

There are many studies supporting the precision of BMD measurements by Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at the proximal femur, before and after implantation of an uncemented prosthesis. DXA periprosthetic analysis is an accurate and reproducible procedure when leg positioning and rotation are precisely maintained (16). Being periprosthetic BMD directly related to the implant design, it is possible to compare the effects of different implants on periprosthetic bone remodeling (17). It might be useful to perform a preoperative DXA analysis to support the choice of implant components.

Periprosthetic BMD and drug therapy

The hypothesis that a pharmacological intervention can interfere with the process of bone loss around the implant, and therefore prevent or delay its loosening has been the aim of several studies (18). The rationale consists of the possibility of blocking the osteoclastic activation which follows both the reduction of the mechanical stress in some areas, as well as the release of local factors, in particular RANK-L, produced during the inflammatory process that is triggered by the presence of debris. Moreover there is also a rationale in favouring the osteoblastic activity and, therefore bone ingrowth.

Suitable drugs to inhibit bone resorption around the implant, are the bisphosphonates (BPs). These drugs reduce bone turnover, inhibiting the osteoclastic resorption, preserve the existing bone architecture and reduce the incidence of osteoporotic fractures, but have a limited action on bone neoformation, as documented by a poor osteoid surface, a low percentage of mineral apposition and a low frequency of activation (19). Several studies demonstrated that bisphosphonates can modulate periprosthetic bone loss related to osteoclastic activity enhanced by cytokines produced during flogistic response to wear debris. BPs can reduce, in a selective way, the osteoclast activity via inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPs) enzyme with consequent decrease of levels of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) enzyme, necessary to prenylation of some Guanosine-5’-triphosphate (GTP) proteins that are essential for cell life (20). BPs also seem to enhance osteocalcin levels, collagen type I and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), that are products of osteoblastic activity in colture. Alendronate, risedronate and zoledronate can increase proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells with a demonstrated upregulation of the genes that codified for BMP-2 and CBFA-1 (Core-Binding Factor A-1) (21). These data seem to support the hypothesis that BPs could have a weak anabolic effect.

Another potential prophylactic approach to reduce periprosthetic bone loss is the use of anabolic agents that could enhance osteointegration by increasing bone formation around the implant.

Teriparatide (1-34-PTH) and parathyroid hormone (1-84-PTH) have been licensed to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis. These anabolic agents exert their action essentially enhancing the number, activity and survival of the osteoblastic cells. For these reasons they seem to represent ideal drugs to increase periprosthetic bone ingrowth (22).

Strontium ranelate demonstrated an action on bone remodelling with a particular mechanism, in fact, it can inhibit bone resorption and, at the same time, stimulate bone formation (23, 24, 25). It has been postulated that Strontium modulates the RANK-L/OPG pathway through its affinity for the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) on the osteoblastic cells. This dual mechanism of action seems to be very interesting in order to enhance periprosthetic bone mass.

Furthermore, other agents such as non steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists (eg, etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab) and interleukin-1 antagonists (eg, anakinra) could be active in preventing osteolysis progression. Etanercept (humans TNF receptor: Fc protein therapy) can reduce osteoclastic bone resorption in vitro and in the mouse calvarial osteolysis model, but it failed to demonstrate an obvious effect in a small sample of patients with osteolysis (26).

RANK-L antagonists (denosumab) are now considered to be the most promising candidates for nonsurgical management of osteolysis. They are potent inhibitors of osteoclasts even more than the bisphosphonates and may offer another future approach to the treatment of established implant loosening or its prevention (27) (Table I).

Table I.

- Potential Drugs for Aseptic Loosening.

| Drug Class | Drug | Approved Indication |

| Bisphosphonates | Alendronate, Risedronate, Zoledronate | Inhibition of osteoclastic activity |

| Anabolic Agents | PTH, Teriparatide, | Stimulation of osteoblastic activity |

| Dual agents | Strontium Ranelate | Inhibition of osteoclastic activity and stimulation of osteoblastic activity |

| NSAIDs | Celecoxib | Inhibition of COX2 and PG2 |

| TNF-antagonists | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab | Inhibition of osteoclastic activity |

| IL-1 Antagonists | Anakinra | Inhibition of osteoclastic activity |

| RANKL- Antagonists | Denosumab | Inhibition of osteoclastic activity |

Animal and Human studies

Numerous studies on animal models demonstrated that bisphosphonates inhibit bone resorption even in the periprosthetic area (28, 29, 30).

Fokter et al. (31) studied the effects of etidronate on periprosthetic, controlateral hip, and spinal bone mineral density in a one-year, perspective, placebo randomized, double-blind study on 46 patients treated with cemented hip arthroplasty. There were no significant differences between mean periprosthetic BMD scores in the two groups, with the exception of the Gruen zone 3 at six months. These findings suggest that cyclic etidronate therapy has no significant effect in suppressing periprosthetic bone loss following cemented hip arthroplasty.

Also pamidronate seems to be uneffective in reducing periprosthetic bone loss. In a case-control study on an animal model, Xing et al. demonstrated that it didn’t enhance osteointegration, measuring bone density around the implant (32).

Shanbhag et al. showed alendronate efficacy to reduce periprosthetic bone loss induced by debris in a canine model of hip arthroplasty (30). Nehme et al. reported that administration of alendronate led to a significant reduction in peri-prosthetic bone loss at 2 years follow-up (33).

Bhandari et al. (34) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo controlled trials to determinate the effect of bisphosphonates on BMD following total joint arthroplasty. By applying strict eligibility criteria only 6 studies were selected. Of these only two were blind. Of the 6 studies, two were related to cementless hip arthroplasties, one to cemented hip prostheses, one to hybrid hip prostheses and two to cemented knee arthroplasties. In 5 of the studies alendronate had been used while pamidronate had been used in the other. BMD decreased in all cases after the third month, but in a significantly lesser percentage in the patients treated with bisphosphonates. This difference persisted at the densitometric evaluation at the 6th month and was confirmed in the cases controlled at 12 months.

Ching-Jen et al. demonstrated that, also in knee arthroplasty, alendronate was active in reducing periprosthetic bone, with persistence of the effect for two years when oral alendronate was given for 6 months (35).

More recently, Arabmotlagh et al. (36) demonstrated, using DXA, that patients treated postoperatively with alendronate (10 mg/day oral alendronate for 10 weeks or with 20 mg/day for 5 weeks) have a beneficial effect that persists at six years after total hip arthroplasty, with no significant changes detected in femoral periprosthetic BMD when compared with results at 1 year. These results suggest that the prevention of femoral periprosthetic bone loss following total hip arthroplasty (THA) achieved by postoperative alendronate is of long-standing effect, and further bone loss does not occur after the first year.

Yamasaki et al. (37) evaluated the effects of risedronate on periprosthetic bone loss after cementless THA. At 6 months postoperative decrease of BMD in the risedronate group was significantly lower than in the placebo group.

Recently it has been demonstrated by Goodship et al. that perioperative administration of zoledronate (10 microg/kg) reduced calcar osteopenia and maintained functional integration of the femoral component in an ovine hemiarthroplasty model (38).

There are few studies investigating the efficacy of bisphosphonates locally delivered by an hydroxyapatite-based site-specific system (39, 40). Suratwala et al. (40) demonstrated that a hydroxyapatite-bisphosphonate composite improves periprosthetic bone quality and osteo-integration of an intramedullary implant even in the presence of ultra-high-molecular weight polyethylene particles in an experimental rat femur model. Periprosthetic bone mass was analyzed by DXA and microcomputed tomography. The results showed a greater BMD in the periprosthetic bone region in the hydroxyapatite-zoledronate group than in the control group. Regression analysis demonstrated a high correlation between periprosthetic bone mass and peak pullout forces.

Conclusions

DXA represents an easy and reliable option to follow the natural history of the bone around a prosthetic implant. At an early stage, it allows to quantify the amount of bone loss at a local level due to the modifications of mechanical loads, related to stress shielding. Moreover in case of wear debris osteolysis, DXA could be useful to study its evolution and the response to the conservative treatment.

References

- 1.Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, et al. The Swedish Total Hip Replacement Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(2):2–20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200200002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kröger H, Venesmaa P, Jurvelin J, et al. Bone density at the proximal femur after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998 Jul;(352):66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santavirta S, Hoikka V, Eskola A, et al. Aggressive granulomatous lesions in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990 Nov;72(6):980–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarmiento A, Gruen TA. Radiographic analysis of a low-modulus titanium-alloy femoral total hip component. Two to six-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Jan;67(1):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatsumi S, Ishii K, Amizuka N, et al. Targeted ablation of osteocytes induces osteoporosis with defective mechanotransduction. Cell Metab. 2007 Jun;5(6):464–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robling AG, Niziolek PJ, Baldridge LA, et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J Biol Chem. 2008 Feb 29;283(9):5866–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin C, Jiang X, Dai Z, et al. Sclerostin mediates bone response to mechanical unloading via antagonizing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 Oct;24(10):1651–61. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris WH. The problem is osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995 Feb;(311):46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasty M. Clinical reviews: particulate debris and failure of total hip replacements. J Appl Biomater. 1993;4(3):273–6. doi: 10.1002/jab.770040310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amstutz HC, Campbell P, Kossovsky N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of wear de- bris-induced osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 Mar;(276):7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotti TN, Smith MD, Findlay DM, et al. Factors regulating osteoclast formation in human tissues adjacent to peri-implant bone loss: expression of receptor activator NFkappaB, RANK ligand and osteoprotegerin. Biomaterials. 2004;25:565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehrke T, Sers C, Morawietz L., et al. Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand is expressed in resident and inflammatory cells in aseptic and septic prosthesis loosening. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:287–294. doi: 10.1080/03009740310003929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmalzried TP, Callaghan JJ. Wear in total hip and knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81:115–136. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang ML, Sharkey PF, Tuan RS. Particle bioreactivity and wear-mediated osteolysis. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albanese V, Santori F, Pavan L, et al. Periprosthetic DXA after total hip arthroplasty with short vs. ultra-short custom-made femoral stems 37 patients followed for 3. Acta Orthopaedica. 2009;80(3):291–297. doi: 10.3109/17453670903074467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franz Martini, Carmen Lebherz, Frank Mayer, et al. Precision of the measurements of periprosthetic bone mineral density in hips with a custom-made femoral stem. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2000;82-B:1065–71. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b7.9791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.B.C. Hendrikus van der Wal, Ali Rahmy, Bernd Grimm, et al. Preoperative bone quality as a factor in dual-energy X-rayabsorptiometry analysis comparing bone remodeling between two implant types. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2008;32:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venesmaa PK, Kröger HP, Miettinen HJ, et al. Alendronate reduces periprosthetic bone loss after uncemented primary total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:2126–131. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arlot M, Meunier PJ, Boivin G, et al. Differential effects of teriparatide and alendronate on bone remodeling in postmenopausal women assessed by histomorphometric parameters. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1244–1253. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luckman SP, Hughes DE, Coxon FP, et al. Nitrogen-containing biphosphonates inhibit the mevalonate pathway and prevent post-translational prenylation of GTP-binding proteins, including RAS. J Bone Min Res. 1998;13:581–589. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Knoch F, Jaquiery C, Kowalsky M, et al. Effects of bisphosphonates on proliferation and osteoblast diffentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6941–6949. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsiridis E, Gamie Z, Conaghan PG, et al. Biological options to enhance periprosthetic bone mass. Injury. 2007 Jun;38(6):704–13. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marie PJ, Hott M, Modrowski D, et al. An uncoupling agent containing strontium prevents bone loss, depressing bone resorption and maintaining bone formation in estrogen-deficient rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:607–15. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marie PJ, Ammann P, Boivin G, et al. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential of strontium in bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:121–29. doi: 10.1007/s002230010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkins GJ, Welldon KJ, Halbout P, et al. Strontium ranelate treatment of human primary osteoblasts promotes an osteocyte-like phenotype while eliciting an osteoprotegerin response. 2009. Osteoporos Int. 20:653–664. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edward M Schwarz, R John Looney, Regis J O’Keefe. Anti-TNF-therapy as a clinical intervention for periprosthetic osteolysis. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:165–168. doi: 10.1186/ar81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsumi R, Hock C, Bechtold CD, et al. Differential effects of biologic versus bisphosphonate inhibition of wear debris-induced osteolysis assessed by longitudinal micro-CT. J Orthop Res. 2008 Oct;26(10):1340–6. doi: 10.1002/jor.20620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandey R, Quinn JM, Sabokbar A, et al. Bisphosphonate inhibition of bone resorption induced by particulate biomaterial-associated macrophages. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:221–228. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millett PJ, Allen MJ, Bostrom MP. Effects of alendronate on particle-induced osteolysis in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84:236–249. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanbag AS, Hasselmann CT, Rubash HE. Inhibition of wear debris mediated osteolysis in a canine total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1997;344:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fokter SK, Komadina R, Repše-Fokter A., et al. Etidronate does not suppress periprosthetic bone loss following cemented hip arthroplasty International Orthopaedics (SICOT) Int Orthop. 2005 Dec;29(6):362–7. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0018-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Z, Hasty KA, Smith RA. Administration of Pamidronate alters bone-titanium attachment in the presence of endotoxin-coated polyetilene particles. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;83(2):354–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nehme A, Maalouf G, Tricoire JL. Effects of alendronate on periprosthetic bone loss after cemented primaty total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice App Mot. 2003;89(7):593–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhandari M, Bajammal S, Guyatt GH, et al. Effect of bisphosphonates on periprostethic bone mineral density after total joint arthroplasty. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:293–301. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ching-Jen Wang, Jun-Wen Wang, Jih-yang Ko, et al. Three-Year changes in bone mineral density around the Knee after a six-month course of oral alendronate following total knee arthroplasty. A Prospective, Randomized Study. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88A:267–272. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arabmotlagh M, Pilz M, Warzecha J, et al. Changes of femoral periprosthetic bone mineral density 6 years after treatment with alendronate following total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res. 2009 Feb;27(2):183–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamasaki S, Masuhara K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Risedronate reduces postoperative bone resorption after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodship AE, Blunn GW, Green J., et al. Prevention of strain-related osteopenia in aseptic loosening of hip prostheses using perioperative bisphosphonate. J Orthop Res. 2008 May;26(5):693–703. doi: 10.1002/jor.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanzer M, Karabasz D, Krygier JJ, et al. The Otto Aufranc Award: bone augmentation around and within porous implants by local bisphosphonate elution. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005 Dec;441:30–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194728.62996.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suratwala SJ, Cho SK, van Raalte JJ, et al. Enhancement of Periprosthetic Bone Quality with Topical Hydroxyapatite-Bisphosphonate Composite. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Oct;90(10):2189–96. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]