Abstract

The human cost of advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for informal caregivers in Canada is mostly unknown. Formal care is episodic, and informal caregivers provide the bulk of care between exacerbations. While patients fear becoming burdensome to family, we lack relevant data against which to assess the validity of this fear. The purpose of our qualitative study was to better understand the extent and nature of ‘burden’ experienced by informal caregivers in advanced COPD. The analysis of 14 informal caregivers interviews yielded the global theme ‘a day at a time,’ reflecting caregivers’ approach to the process of adjusting/coping. Subthemes were: loss of intimate relationship/identity, disease-related demands, and coping-related factors. Caregivers experiencing most distress described greater negative impact on relational dynamics and identity, effects they associated with increasing illness demands especially care recipients’ difficult, emotionally controlling attitudes/behaviors. Our findings reflect substantial caregiver vulnerability in terms of an imbalance between burden and coping capacity. Informal caregivers provide necessary, cost-effective care for those living with COPD and/or other chronic illness. Improved understanding of the physical, emotional, spiritual, and relational factors contributing to their vulnerability can inform new chronic care models better able to support their efforts.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), informal caregiving, vulnerability, coping

Introduction

Any consideration of the burden of chronic disease in Western society must acknowledge the significance of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) because of its rising prevalence, morbidity, and attributable mortality.1,2 In Canada this trend will soon result in more women than men living with COPD.3,4 The cost of treatment of physical symptoms and acute exacerbations is significant,5 but ignores the hidden cost-savings realized from contributions by informal caregivers (families and/or friends) who provide the bulk of care at the cost of possible physical, psychosocial, and/or spiritual effects.6 In the US, extra hours necessitated for informal care of elderly patients with chronic lung disease have been estimated at $1.8–$3.5 billion in invisible costs per year.7 While informal caregiving undoubtedly provides value in terms of delaying or preventing costly institutionalization of those with chronic illness,8 a recent Australian study has suggested that ‘ways of better supporting caregivers is a direct challenge for health and social services, especially given the likely burden that people have with end-stage lung disease (ESLD)’.9 Despite its potential economic, personal, and institutional significance, the human cost to informal caregivers has not been well explored in Canada.

Informal caregiving refers to ‘the act of providing assistance to an individual with whom the caregiver has a personal relationship’10 and informal caregivers refers to those who ‘provide unpaid help or supervision to persons with one or more disabilities’.11 Significant but variable physical, emotional, psychosocial, and financial impact has been reported in previous studies of informal caregiving in various chronic illnesses10,12–19 but some caregivers also associate positive effects such as enhanced self-esteem and/or self-efficacy, personal growth, and insight with their role.20,21 Despite this positive potential, formal research aligned with disease theory and pathophysiology has for the most part labeled and explored the construct as ‘caregiver burden.’

Caregiver burden has been defined as ‘the strain or load borne by a person who cares for an elderly, chronically ill, or disabled family member or other person’.10 It is thought to have at least two main components: objective burden, ‘the time spent on care giving, the care-giving tasks that are performed, and possible financial problems,’ and subjective burden, ‘the physical, psychological, social, and emotional impact caregivers experience in giving care’ or how caregivers feel about providing care.22 Viewed generically, it appears to arise as part of a complex interaction affected by personal elements like caregiver personality, experience, and sense of self-efficacy; relational elements like the care recipient’s quality of life and degree of suffering, disability, adjustment, and coping, as well as the strength and nature of the relationship between caregiver and care recipient; and environmental elements such as perceived support (formal and informal) and financial resources.14,18,23

Results of US, UK, and European studies examining the nature of informal caregiving in COPD have suggested significant burden. The role can be relationally and personally demanding, at times lonely and depressing, and tends to lack professional, financial, and/or psychosocial support.24–29,88 Caring for older patients more dependent for activities of daily living, incontinent, and less financially secure has been associated with more caregiver distress.30,31 Previous studies have alluded to the significant potential for those living with COPD to experience erosion of the intimacy dimension of relationships.32,33 Negative effects on family and friendship arise in connection with increasing frustration, irritability, belligerence, emotional lability, and other mood disturbances common in those living with advancing COPD.20,33–35

In a study by Bergs,20 wives caring for spouses with advanced COPD described their role as ‘duty’ but some also alluded to a desire to ensure their dying loved one had optimal care until the end of life, factors that motivated them to persevere in revising relationships and negotiating role expectations with their spouses.20 Previous work suggests the relational demands arising from differing role expectations between care recipients and caregivers are a significant source of distress in COPD caregiving.31,34

Proot et al16 theorized that the balance between illness burden and coping capacity could reflect informal caregivers’ vulnerability to fatigue and eventual burnout.16 Further, they suggested personal, relational, and cultural factors would affect this balance and thus increase the vulnerability risk.16 Nevertheless there seems to be a disturbing but ongoing tendency to fail to appreciate the contributions of informal care-givers in COPD settings despite their obvious significance to care recipients, the health care system, and society.8,27,28,36 To begin to correct this tendency we need a better understanding of the impact of COPD on informal caregivers in Canadian settings, particularly in terms of burden, coping, and vulnerability over the longer term.

Method

Following local Research Ethics Board approval we conducted interviews with 14 informal caregivers of patients diagnosed with advanced COPD and followed by the New Brunswick Extra Mural Program (NBEMP) – a well-established, multi-disciplinary, homecare support team. We used ‘interpretive description,’ a qualitative approach that facilitates enhanced clinical understanding of complex health-related experiences with the goal of informing clinical practice related to the phenomenon of interest.37 This approach has capacity to be inclusive of constructed and contextual uniqueness as well as commonalities, thus preserving something of the complexity and messiness of human illness experience (in our case the experience of those providing informal care to patients living with advanced COPD in a nonacute, Canadian rural setting).38 Data collection included a one-on-one, hour-long interview with each informal caregiver using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix A) to encourage conversation about their informal caregiving experiences.

Using a ‘purposive’ approach, we recruited an initial, homogeneous group39 of individuals who could give us rich detail about their experience. We enrolled an informal caregiver for each of 14 eligible patients being followed by NBEMP for their severe or moderate COPD. Eligible patients were identified using a pre-defined set of criteria for advanced COPD according to CTS criteria (Appendix B). The informal caregiver was identified by the patient as the unpaid individual involved to the greatest degree in providing in-home care. Caregiver inclusion criteria included: a) English speaking; b) providing ‘informal care’ for a patient with advanced COPD for at least 6 months; c) personal health status not precluding meeting and engaging in an interview of approximately one hour. We sought to recruit 10–12 participants as the basis of a preliminary analysis,40 and this increased to 14 in line with the concept of ‘content saturation’ (when the interviewer assesses s/he is hearing few if any new findings despite additional interviewees [refer Notes]). See Table 1 for an outline of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Description of participants

| Caregiver (CG) | Gender | Age (CG) | Age (Pt) | SES1 | Education | Care recipient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMP001 | female | unknown | 56 | low | some college | husband |

| EMP002 | female | 59 | 79 | low-mid | high school grad | husband |

| EMP003 | female | 65 | 67 | low-mid | some college | husband |

| EMP004 | female | 61 | 69 | low-mid | trade school | husband |

| EMP005 | female | 62 | 61 | low | some high school | husband |

| EMP006 | female | 70 | 73 | low | high school grad | husband |

| EMP007 | female | 57 | 62 | low-mid | high school grad | husband |

| EMP008 | male | 46 | 71 | low-mid | some high school | female partner |

| EMP009 | female | 89 | 88 | low | some high school | husband |

| EMP010 | male | 57 | 87 | low | some high school | mother |

| EMP011 | male | 71 | 67 | low-mid | some high school | wife |

| EMP012 | female | 70 | 78 | low | some college | husband |

| EMP013 | female | 70 | 70+ | low-mid | high school grad | husband |

| EMP014 | female | 49 | 82 | mid-high | some college | mother |

Notes: Low: $0 ≤ $25,000; Low-Mid: $25001–50,000; Mid-high: $50,001–100,000; High: >$100,001.

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

Following verbatim transcription of digitally recorded interviews, a research assistant experienced with the NVivo 7.0™ qualitative analysis software program developed codes and initial themes using a standard constant comparison method seeking commonalities and particularities across and within transcripts.37 Using the analytic lens of ‘burden/distress’ we sought patterns and themes related to the more negative aspects of informal caregiving as described by our participants.37

We were attentive to the following criteria for judging rigor in clinically oriented qualitative studies: 1) method appropriate to the question; 2) sampling adequate and information rich; 3) iterative research process; 4) thorough and clearly described interpretative process; 5) reflexivity addressed.41 We used Attride-Stirling’s (2002) ‘thematic network’ approach to cluster codes into basic, organizing, and global themes reflecting an increasing level of abstraction.42 Interpretation was inevitably influenced by the investigators’ diverse professional backgrounds (medical [GR], respiratory therapy [JY], and psychospiritual [CS]). The discussion of interview data, contextualizing field notes, and emerging consensus from our different perspectives helped broaden and strengthen the analysis and reflexivity.

Findings

Caregivers described their experience as a series of ‘ups-and-downs.’ Their stories told of a continuing process of major and minor biographical life changes as care recipients’ illness progressed. A common response to these ongoing changes was to apply a day at a time framework to life. This became the study’s global theme as it seemed to capture something of the vulnerability we heard in their stories of unpredictable losses.

A day at a time …

It was a theme about surviving, persevering – an echo in every interview whether the interviewee’s experience of caregiving was positive or more negative. It often prefaced or summed up responses to questions about hope, fear, coping, burden, and overall assessment of the experience.

Usually if you look ahead, and then things just get messed up anyway. So you plan ahead and it don’t work. Most of the time, something either steps in the way or something like that there. So that is why I take the days as they come.

(EMP008)

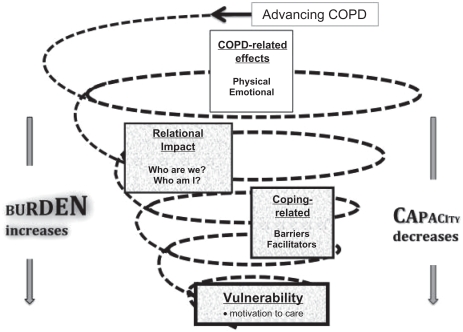

Most of our participants were females caring for male partners with advanced COPD and many seemed to be struggling. They frequently spoke of their distress in terms of relational changes. Exploring this notion of relational impact, what we heard suggested a downward spiral effect, ie, disease-related issues appeared to initiate or escalate a negative relational impact that in turn impacted coping efforts which then affected the already changing relational dynamic and so on. We identified three contributors to this spiral – relational impact influenced by disease-related factors, affecting and affected by coping-related factors. Each of these elements is pictured in Figure 1, a concept map of the interaction.

Figure 1.

Caregiver vulnerability concept map.

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Relational impact

The cumulative effect of illness-related losses for the care recipient – lung capacity, mobility, and independence – often leads to losses related to social life, personal freedom, and security/stability for the caregiver, a situation caregivers experienced as negative change in familiar partnership/relational patterns. As the disease progressed shared activities, familiar ways of being together as a couple and as family tended to dwindle and for some completely disappear. The ongoing shift/loss of previous ‘couple-hood’ identity confronted affected caregivers with the question: who are we now and who am I? We heard the effects of this obviously unexpected but ongoing issue as a range of painful emotions – anger, grief, powerlessness, loneliness, guilt, and confusion – that culminated in questions of personal identity and self-concept. For some it led to a realization that intimacy and caring feelings for their partner were quickly disappearing. For these individuals caregiving had become a demoralizing process that undermined their motivation both as partner and caregiver. Despite the burdensome nature of this reality, they persevered because of duty, a concept they often described in terms of marriage vows (for better or for worse) and societal expectations. To sum up, the burden of disease-induced relational impact for caregivers appeared to reside in the questioning/shift/loss of relational and personal identity, self-concept, and caregiving motivation. We explored each of these elements further.

Who are we now? Who am I?

These were dynamics that demanded a constant personal adjustment by caregivers to their existing relational ‘partnership.’ Often they perceived the adjustment as entirely one-sided with the caregiver feeling the burden/distress of trying to anticipate and accommodate to the constantly shifting, impoverished relational landscape. This shift toward the care recipient’s increasing dependence on the caregiver imposed a negative effect on any existing relational mutuality/reciprocity dynamics.

Companionship … everything … I don’t have a partner. I have another child. He knows that. I’ve told him, you know. and he said, “Well, I love …[pause] I need you,” and I said, “I don’t want to be needed.” and, oh, I cry a lot and then I pick up.

(EMP001)

Caregivers’ relational issues were encompassed in the questions who are we? who am I? associated with four factors: shifting roles, care recipients’ negative attitudes and behaviors, social isolation, and impact on family.

Shifting roles

These changes appeared to result from caregivers’ gradual shouldering of responsibilities previously held by care recipients. Even in cases where the caregiver seemed well adjusted to these changes, we noted an implicit acknowledgement of the additional load. Part of this dynamic for many caregivers was a perceived loss of ‘self,’ an emerging confusion about personal identity. For some a sense of grieving, for others anger and/or bitterness over the loss of relationships, roles, identity synonymous with a ‘better time’ figured in this.

Over the last 8–9 years, I feel inside that my role’s completely changed. Somewhere in all of this, I’ve lost who I am. I’m more like his nurse or ‘I need you’ kind of thing. That’s it – I need you, and I don’t know how to explain it. I just feel like somewhere me, myself, I’m lost. I don’t know who I am any more. I don’t know if anybody can understand that.

(EMP001)

Care recipients’ negative attitudes/behaviors: Caregivers described care recipients’ frequent belligerent, resistant moods, ongoing efforts to manipulate caregivers to be at their beck and call, and frustrating reluctance to participate in activities of daily living, treatment regimes, and general self-care at a level compatible with diminishing capabilities. Many found these dynamics profoundly distressing.

He’s very controlling .... he’s got me under his thumb. If he thinks I’m going to go somewhere and do something, he’ll find some way to get himself run down so I won’t be able to leave the house. He wants to know where I am 24/7 ...

(EMP007)

These behaviors left caregivers resenting the increasingly one-sided nature of the relationship and wondering why they continued to provide care since the care recipient appeared not to appreciate their efforts or even want to live. This led to a loss of caring motivation and intimacy feelings for the care recipient. Although these dynamics were most obvious in the interviews in situations where females were providing care for male spouses, most interviews alluded to it in some way.

I am living with a totally different man. My husband that I met, he was spotless clean. You know, he ate everything. He wasn’t fussy. So I mean it’s totally different, and, I mean, to be honest, I don’t have the feelings for this man. I really don’t.

(EMP004)

Social isolation

Caregivers expressed this in terms of feeling housebound and limited in companionship due to anxiety/guilt about leaving the care recipient alone, particularly when there was little family or community contact. The dwindling of relational networks also appeared to play a role in the evolution of self-concept/personal identity confusion. Caregivers experiencing this distress found it worsened as the patient’s illness advanced.

Everybody used to come here, “Can I use your garage? Can I use this tool?” You know, there was always somebody coming and going. Now, it’s like … Well, he said to one person one day, “You know, it’s not contagious what I have.”

(EMP005)

Impact on family

There were frequent comments about the negative impact of the illness on the family. Caregivers linked this to negative effects of the illness on the care recipient’s emotional/cognitive status such that s/he (and thus caregiver) experienced family visits as too stressful, or the caregiver felt unable to leave long enough to visit family. Either way it constrained caregivers’ sense of personal freedom.

Her husband said, “I can see a change in the family. The family is all going to hell” was his exact words because he said everybody always used to come home, and everybody barbequed, but now it’s just dwindling you know. So he said you fellows were so close.

(EMP004)

Disease-related factors

Caregiver distress or burden linked to this negative relational impact appeared to arise from particular disease-related elements that we categorized as physical and emotional.

Physical demands

These encompassed all the day-to-day tasks caregivers felt compelled to take on because of the patient’s illness, both direct disease-related tasks and added responsibilities from roles newly assumed due to lack of ability or willingness of care recipients. For a few, these tasks were in addition to outside employment. Within this category we identified three contributing factors. Although the list of possible COPD-specific demands such as monitoring breathlessness, medications, and treatment regimen adherence, attending to daily nutrition, helping with personal hygiene, dressing, and toileting did not apply in every case, the tasks that were perceived as additional burden particularly in cases where the care recipient refused to engage despite continuing capacity to do so. Many of the care recipients had other chronic conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and/or diabetes in addition to their COPD, and these co-morbidities added to the workload and thus the substance of caregiver burden. Finally caregiver health/fatigue was also a factor in how the burden of increasing disease-related demands was perceived and dealt with. Several of the study participants were struggling with significant diagnoses that left them feeling more physically and/or emotionally depleted than might otherwise have been the case.

I am not as good as I used to be. I don’t have the strength that I had too. We’re wondering what is going to happen because I start treatments [for stage IV cancer] again on Wednesday and I know that I am going to lose some strength and I don’t know ...

(EMP003)

Emotional demands

Caregivers exhibited and talked about their emotional reactions to the effects of worsening COPD and relational changes. One of the most distressing for caregivers was the hypervigilance that accompanied their fear and anxiety, and heightened the burdensome relational impact, even for those caregivers who experienced the role more positively.

I didn’t sleep at night. I was just afraid that he might take the oxygen off, and then like I said, the power was another thing. But I was always afraid because he’s sort of thrashy sometimes in the bed and stuff. And I’m thinking if that goes off, am I going to know that it’s off? Is he going to lay there how many hours without me knowing it? I worried about everything. So for months, I didn’t sleep.

(EMP006)

Financial implications of the disease, (medications, oxygen in some cases, loss of care recipient’s income/pension/insurance) particularly for those with little or no employment pension/income and only provincial health insurance added to the anxiety for some. As well, care recipients’ worsening illness, breathlessness, dependency, negative attitudes and behaviors often engendered feelings of helplessness/ powerlessness that were an additional source of stress. Additionally, caregivers described feelings of anger (often associated with frustration/resentment/bitterness linked to the perception of a loss of personal freedom and/or injustice), grief, sadness, depression, and/or guilt/shame, a range of emotions arising from their day-to-day experience of caregiving. The role may become an exercise in ‘duty’ and guilt leading to a coping stance of resentful perseverance.

So, it’s me and sometimes I do feel alone. I feel very alone and, so yeah, sometimes I have that resentment and I immediately feel guilty because I feel resentful.

(EMP014)

Coping-related factors

When asked about how they coped with these effects, caregivers told us about things that helped, things that hindered, and things they felt they needed but currently lacked. We categorized these coping-related factors as facilitators and/or barriers. Although these lists seemed straightforward, the fact that some issues appeared in both categories suggests something of the individual and complex nature of the needs dynamics that contributed to a sense of stress unique to each situation. An illustration of this is our finding that some caregivers described hospitalization of the care recipient as respite, others as stress.

Facilitators

Caregivers described interpersonal and intrapersonal resources they relied on to get them through. Interpersonal supports included things like family, pets, social networks, and help in terms of financial and formal medical system support such as homecare, NBEMP personnel, and caring physicians. Intra-personal factors included disease-specific skills/education, faith/spirituality resources, hope, past caregiving experience, planning and preparation, and approaches to self-care like getting out for a walk, reading, taking time for self – behaviors helpful and meaningful to individual caregivers.

I will say that without the Extra Mural Care program being in place, I would not be able to do what I am doing. Every one of them that comes in, they are excellent, and I can pick up the phone and call them any time at all.

(EMP007)

Barriers

These were factors caregivers spoke of as making coping harder and mostly were related to gaps in support services and relevant resources. In this category caregivers identified a lack of (in order of frequency): respite which they associated with preventing fatigue, preserving personal freedom, and enabling self-care; easier access to oxygen-related resources; financial support; disease-specific information, education, and skills training; accessible peer support; accessible expert support – guidance/counseling; consistency with respect to home care workers; and appropriate attention from health care particularly with respect to potential for caregiver stress in relation to care recipients’ hospitalizations. For study participants, this list of barriers was longer than the list of facilitators, a fact that reflected once again the burdensome nature of their role.

If I could get away for a week or two weeks, but, you see, what comes with that is I don’t have anywhere to go. What would I do?

(EMP001)

I don’t know where I am going. I don’t know what I am going to do. I don’t know how I am going to be financially able to keep the house up, the taxes and the mortgage, and all the things that goes with everyday life. I don’t know ...

(EMP002)

To summarize, informal caregivers of patients with advanced COPD were experiencing considerable burden connected to their role. Increasing disease-related demands contributed to the development of a negative relational impact that decreased the caring motivation and intimacy feelings of many caregivers who then experienced more stress and vulnerability in their effort to cope.

Discussion

A profound relational impact from the illness was central to their experience of burden for many informal caregivers in advanced COPD. Worsening COPD imposed an increasing physical and emotional burden on care recipients and their caregivers. These effects gave rise to stressful relational shifts/losses that challenged their coping capacity particularly for many female spousal caregivers. And these coping difficulties in turn appeared to reinforce ongoing dynamics of negative relational change. Many of our participants were feeling confused, anxious about the future and thus quite vulnerable. They had adopted a ‘one day at a time’ approach to life as a coping response in the face of a past and present reality shaped by the stressful uncertainty of ongoing disease-imposed change. ‘One day at a time’ seems to reflect efforts to avoid feelings of distress/burden linked to uncertainty and unpredictable but inevitable losses in the future. This day-to-day pursuit of coping equilibrium echoes and extends the ‘caregiver vulnerability’ framework proposed by Proot et al16 who described it in terms of a balance between caring burden and coping capacity. For many of our participants, vulnerability to fatigue, demoralization, and burnout was experienced as a downward spiral (see Figure 1) that seemed to increasingly threaten what was often an already precarious balance.

The first element in this spiral was worsening COPD-related illness effects. These impacted relational dynamics and contributed to the development of caregiver distress/burden. Care recipients’ increasing dyspnea, immobility, negative self-concept, and dependence appeared to precipitate and/or accelerate significant, often negative shifts in couples’ previous relational equilibrium. This shift was often accompanied by an alteration in their mutuality/reciprocity patterns with significant implications for partner intimacy, self-concept, and motivation. Primary factors in this relational change component of the spiral were care recipients’ negative attitudes, treatment nonadherence, and quarrelsome, reclusive behaviors. These descriptions are consistent with previous COPD research in this area.20,33–35

Depression can play a significant if often overlooked role in this negative relational impact. It is highly likely that care recipients in our study were living with some degree of depression/anxiety with all the attendant implications for relational effects on their informal caregivers. One such effect, the second contributing factor to relational impact, was an increasing social isolation that arose as care recipients became more reclusive, anxious, and dependent. This isolating effect moved them further down the spiral and for some led to decreasing contact with the wider family, exacerbating an already negative disease-related relational impact. For many, the gradual loss of family contact, social networks, and socially based activities contributed significantly to the burden of the relational impact.

This relational impact was experienced by many as a sense of loss of ‘couple’ identity and was often accompanied by personal identity confusion. These feelings emerged within a context of changing roles, added responsibilities, and expectations that left some feeling they had lost themselves in the process, a result also described by Bergs.20 In our case, caregivers blamed disease-related factors including the physical demands of disease-specific tasks as well as role and expectation changes and an array of resulting, painful emotions that further eroded caring motivation for many.

Ultimately caregivers’ struggle to assimilate evolving relational and identity shifts appeared to challenge both their motivation to care and their role satisfaction. For many, the care recipient was no longer the person they had once loved. Lack of explicit appreciation for the care provided and/or apparent devaluing of life itself by care recipients left some caregivers wondering why they were bothering. Many described their motivation in terms of a ‘duty’ to care imposed by marriage vows and/or societal norms, a reality also described by Bergs.20 Caregivers’ burden seemed largely a reflection of the stress associated with a disease-initiated process of relationship revision and negotiation that to them felt increasingly one-sided, lonely, unexpected, and unfair.

The interaction of factors related to distress/burden was uniquely expressed in each caregiver/care recipient household suggesting that burden is best understood within the context in which it arises. COPD is not an isolated phenomenon, but the result of an ongoing series of complex interactions, an evolving process superimposed on an already existing, shifting relational matrix – a family biography and ethos. Often in cases where caregivers seemed angry, frustrated, resentful, and struggling to maintain caring motivation we heard relational histories complicated by factors known to be associated with increased psychological and physical effects on caregivers such as alcoholism, emotional abuse, unemployment, poverty, other illnesses. Most of the participants reported income levels at or below poverty levels, most had less than a high school education, and many had chronic conditions of their own.43

For those with previously stable, more harmonious relationships there was more role satisfaction and less perceived burden, but the caregiving experience was not stress-free. Instead of being rooted in relational conflict and tension, distress arose from anticipatory grieving. A history of a close relationship seemed to increase the likelihood of vicarious suffering and feelings of anxiety and powerlessness in the face of increasing illness effects. Although distressing, these dynamics did not seem to adversely affect caring motivation and coping capacity. Previous relational health appears to supplement emotional capital adequately, leaving resources in the intrapersonal caring ‘bank’ sufficient to reinforce coping resiliency in the face of increasing demands imposed by relational disease-related effects.36,44

In summary, it seems reasonable to suggest that patients living with COPD have a legitimate concern about their potential to be a burden to their families45 and that the burden is real. If it is our laudable and oft stated goal to provide care that maintains these patients in their homes and decreases costly episodes of institutionalization, we have to acknowledge this burden and its resulting vulnerability for informal caregivers and begin to respond with relevant assessment and support strategies.

Conclusion

As COPD advances to late stages, it traps many patients and their caregivers in a downward spiral of physical, social, and emotional effects that exact a severe relational toll, particularly for those with a previous history of partnership stress. It appears that we (in the formal health care system) ‘use’ and in all probability ‘abuse’ informal caregivers. We do little to support this population yet expect them to cope and provide the bulk of noninstitutional care no matter what their circumstances. The result is some very vulnerable, dispirited, and fatigued care providers, particularly in the context of families we may find more challenging to deal with, but who need care sensitive to physical, emotional, social and/or spiritual dimensions. We need to recognize the justice and risk implications inherent in the ‘caregiving on the edge’ spiral and rethink models of care accordingly. By continuing to ignore the potential for substantial vulnerability in those providing informal care for patients living with COPD we will also continue our complicity in the delivery of less than adequate care to this population.

Clinical implications

The goal of avoiding institutionalization will fail without committed, capable informal caregivers to support those living with advancing COPD.

Negative relational impact associated with COPD demands is a common occurrence that increases caregiver burden and thus vulnerability to fatigue and burnout.

Caregiver vulnerability risk increases with previous history of relational stress, conflict, instability, and coexistence of social determinants such as poverty, low education level, and coexisting health conditions.

There is a role for needs assessment processes that encompass caregivers as well as patients and include a comprehensive family and psychosocial history.

Intervention strategies should address coping facilitators (respite, financial help, homecare, medical support, self-efficacy, disease-related education and experience, planning, hope/faith/spirituality resources, contact with family, friends, and/or community groups, access to social-networking technology, self-care practices); and barriers (lack of disease-specific information, education, training, emergency contact information, simpler access to oxygen-related resources, financial, consistent homecare, respite, emotional support from peers, family, and/or experts) as identified by informal caregivers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance graciously contributed by Dr Raewyn Bassett, qualitative research consultant to CDHA and Dalhousie University Faculty of Health Professions. This study was supported by funding from the Medical Research Fund of New Brunswick and by Dalhousie University’s network of end of life studies (CIHR- ICE Grant HOA-80067).

Appendix A. Preliminary interview guide

- Demographics: Your relationship to “X”? How long have you been providing care at home for “X”? Prompts:

- What sorts of care do you provide? How much of your day does it take?

- Has this changed over time?

- Do you have any help with it? What has that been like for you?

- Have you ever known anyone else with this disease? Have you ever cared for anyone with a chronic condition or who was very sick? (if yes, what was that like for you; is caring for “X” like this?)

- Were you working outside the home before “X” got sick? If yes, when and why did you stop this job?

- Was “X” working when he was diagnosed with this lung condition? If yes, how long was he able to continue working?

- Has life changed for you since you have been caring for “X” at home? Prompts:

- In what ways? Has it affected your usual daily routine (what would your day have been like before; what is it like now? How would you describe what you do? How do you feel doing this job? Are there good things about it?

- Is it becoming harder or easier to care for “X”? In what ways?

- What do you find hardest about caring for “X”? What bothers you about it?

- Loneliness?

- Vulnerability/insecurity?

- Fear/anxiety

- Isolation?

- Financial difficulties

- What worries you most?

- Do you think you have hope? – tell me about that (or lack of hope).

Is this a change? If yes, in what way(s)?

- What helps you in caring for “X”?

- What helps you cope? (supports, faith, recreation, family, other)

- Are there people or things that make it easier to do what you do for “X”? Do you get help/support from anyone?

Has the illness changed things for your family? In what ways?

What has it been like for you dealing with X’s doctors, nurses, or others you have to see for treatment or care? What about the hospital – what has that been like? What was helpful, what wasn’t? What was missing? Did you get the information you wanted/needed? Did you understand what they wanted/needed you/X to do? What would have made it better for you?

- Is there anything that would make caring for “X” easier or better for you? Is there anything “X” needs that you don’t have now? What do you need for yourself?

- Respite

- Someone to stay at night

- Home care nurses trained to care for this kind of lung condition

- Does it seem like a burden?

- How does it make you feel? eg, some have said resentful, guilty, helpless, powerless, sad?

- Do you feel you have a choice – would you be free to leave if you wanted to?

- Have you ever thought about leaving? (when, why, what stopped you)

- Why do you think you stay? Is there anything that would cause you to leave?

Summary question:

3. Is there anything else you think I should know or you would like to tell me about caring for “X”?

Appendix B. Canadian Thoracic Society Criteria for defining severe and moderate COPD

Severe: shortness of breath resulting in the patient being too breathless to leave the house, or experiencing breathlessness after dressing/undressing (Medical Research Council [MRC] score of 5), and/or the presence of chronic respiratory failure (PaCO2 > 45) or clinical signs of right heart failure.

Moderate: shortness of breath causing the patient to stop walking after 100 meters or a few minutes on the level (MRC score of 3–4) with at least one of the following: BMI < 21; post-bronchodilator FEV1 <30% predicted; one or more hospital admissions for acute exacerbation of COPD in the previous year.

Notes

One note to this observation, the researchers would have incorporated additional interviews with male caregivers and with caregivers caring for an aging parent, but we experienced difficulty finding these potential participants.

Footnotes

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this paper.

References

- 1.Gore JM, Brophy CJ, Greenstone MA. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax. 2000;55(12):1000–1006. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lung Association Women and COPD: A National Report. 2006.

- 4.Public Health Agency C Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) facts and figures. [online] Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2008. [updated 2008]. Accessed Mar 18 2010. Available from: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/crd-mrc/copd_figures-mpoc_figures-eng.php#6-1 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson AC, Rocker GM.Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: rethinking models of care QJM 2008. hcn087 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Skilbeck J, Mott L, Page H, Smith D, Hjelmeland-Ahmedzai S, Clark D. Palliative care in chronic obstructive airways disease: a needs assessment. Palliat Med. 1998;12(4):245–254. doi: 10.1191/026921698677124622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langa K, Fendrick A, Flaherty K, Martinez F, Kabeto M, Saint S. Informal caregiving for chronic lung disease among older Americans. Chest. 2002;122(6):2197–2203. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caress AL, Luker KA, Chalmers KI, Salmon MP. A review of the information and support needs of family carers of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:479–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currow DC, Agar M, Sanderson C, Abernethy AP. Populations who die without specialist palliative care: does lower uptake equate with unmet need. Palliat Med. 2008;22:43–50. doi: 10.1177/0269216307085182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasaya R, Polgar-Bailey P, Takeuchi R. Caregiver burden and burnout. Postgrad Med. 2000;108(7):119–123. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2000.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bainbridge HTJ, Cregan C, Kulik CT. The effect of multiple roles on caregiver stress outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(2):490–497. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannuscio C, Jones C, Kawachi I, Colditz G, Berkman L, Rimm E. Reverberations of family illness: A longitudinal assessment of informal caregiving and mental health status in the nurses’ health study. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(8):1305–1311. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faison K, Faria SH, Frank D. Caregivers of chronically ill elderly: perceived burden. J Commun Health Nurs. 1999;16(4):243–253. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1604_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Kim DK, Kim JH. Stress in caregivers of demented people in Korea – a modification of Pearlin and colleagues’ stress model. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:784–791. doi: 10.1002/gps.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohman M, Soderberg S. The experiences of close relatives living with a person with serious chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(3):396–410. doi: 10.1177/1049732303261692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proot I, Abu-Saad H, Crebolder H, Goldsteen M, Luker K, Widdershoven G. Vulnerability of family caregivers in terminal palliative care at home; balancing between burden and capacity. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17(2):113–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitaliano P, Katon W. Special report: Stress. effects of stress on family caregivers: Recognition and management. Psychiatr Times. 2006;23(7):24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yates ME, Tennstedt S, Chang BH. Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. J Gerontol. 1999;54B(1):P12–P22. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGarry J, Arthur A. Informal caring in late life: a qualitative study of the experiences of older carers. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(2):182–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergs D. ‘The hidden client’ – women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(5):613–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med. 2005;19:21–32. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Exel N, Brouwer W, van den Berg B, Koopmanschap M, van den Bos G. What really matters: An inquiry into the relative importance of dimensions of informal caregiver burden. Clin Rehab. 2004;18(4):683–693. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr743oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bookwala J, Schulz R. A comparison of primary stressors, secondary stressors, and depressive symptoms between elderly caregiving husbands and wives: The caregiver health effects study. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(4):607–616. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Booth S, Silvester S, Todd C. Breathlessness in cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Using a qualitative approach to describe the experience of patients and carers. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:337–344. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guthrie SJ, Hill KM, Muers MF. Living with severe COPD. A qualitative exploration of the experience of patients in Leeds. Respir Med. 2001;95:196–204. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narsavage GL, Chen K. Factors related to depressed mood in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after hospitalization. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26(8):475–482. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000335606.45977.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasson F, Spence A, Waldron M, et al. Experiences and needs of bereaved carers during palliative and end-of-life care for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Care. 2009;25(3):157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gysels M, Higginson I. Caring for a person in advanced illness and suffering from breathlessness at home: Threats and resources. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:153–162. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gysels M, Bausewein C, Higginson I. Experiences of breathlessness: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:281–302. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas S, Daly B, Kelley C, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128(6):3925–3936. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried T, Bradley E, O’Leary J, Byers A. Unmet desire for caregiver-patient communication and increased caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrieri-Kohlman V, Gormley JM, Mahler DA. Dyspnea. New York NY: Marcel Dekkers; 1998. Coping strategies for dyspnea; pp. 287–320. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolson P, Anderson P. Quality of life, distress and self-esteem: A focus group study of people with chronic bronchitis. Br J Health Psychol. 2003;8:251–270. doi: 10.1348/135910703322370842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Low G, Gutman G. Couples’ ratings of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ quality of life. Clin Nurs Res. 2003;12(1):28–48. doi: 10.1177/1054773803238739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seamark DA, Blake SD, Seamark CJ, Halpin DM. Living with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): perceptions of patients and their carers. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Palliat med. 2004;18(7):619–625. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm928oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyle AH. An integrative review of the impact of COPD on families. South Online J Nurs Res. 2009;9(3):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorne S, Reimer Kirkham S, O’Flynn-Magee K.The analytic challenge in interpretive description [online] 200431Accessed Mar 18 2010. Available from: http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/3_1/pdf/thorneetal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravenscroft EF. Diabetes and kidney failure: how individuals with diabetes experience kidney failure. Nephrol Nurs J. 2005;32(4):502–509. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Third ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. Qualitative designs and data collection. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Second ed. London: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 397–434. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytical tool for qualititative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz R, Sherwood P. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ekwall AK, Hallberg IR. The association between caregiving satisfaction, difficulties and coping among older family caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:832–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Heyland DK. Toward optimal end-of-life care for patients with advanced chronic pulmonary disease: insights from a multicentre study. Can Respirol J. 2008;15(5):249–254. doi: 10.1155/2008/369162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]