Abstract

We have investigated the genetics and molecular biology of orange flesh colour in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). To this end the natural diversity in three genes of the carotenoid pathway was assessed by SNP analyses. Association analysis was performed between SNP haplotypes and flesh colour phenotypes in diploid and tetraploid potato genotypes. We observed that among eleven beta-carotene hydroxylase 2 (Chy2) alleles only one dominant allele has a major effect, changing white into yellow flesh colour. In contrast, none of the lycopene epsilon cyclase (Lcye) alleles seemed to have a large effect on flesh colour. Analysis of zeaxanthin epoxidase (Zep) alleles showed that all (diploid) genotypes with orange tuber flesh were homozygous for one specific Zep allele. This Zep allele showed a reduced level of expression. The complete genomic sequence of the recessive Zep allele, including the promoter, was determined, and compared with the sequence of other Zep alleles. The most striking difference was the presence of a non-LTR retrotransposon sequence in intron 1 of the recessive Zep allele, which was absent in all other Zep alleles investigated. We hypothesise that the presence of this large sequence in intron 1 caused the lower expression level, resulting in reduced Zep activity and accumulation of zeaxanthin. Only genotypes combining presence of the dominant Chy2 allele with homozygosity for the recessive Zep allele produced orange-fleshed tubers that accumulated large amounts of zeaxanthin.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11103-010-9647-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Solanum tuberosum, SNP analysis, Allele mining, Orange flesh, Carotenoids, Zeaxanthin epoxidase

Introduction

Flesh colour in most tetraploid potato cultivars ranges from white via cream and yellow to dark yellow. This yellow colour is caused by the presence of specific carotenoids. A small number of cultivars have red or blue/purple flesh, caused by the presence of anthocyanins.

The main carotenoids present in cultivated potato are lutein, violaxanthin, zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin (Breithaupt and Bamedi 2002; Brown et al. 1993; Iwanzik et al. 1983; Nesterenko and Sink 2003). Beta-carotene, the precursor of vitamin A, is almost absent in S. tuberosum genotypes or closely related Solanum species (Breithaupt and Bamedi 2002). Carotenoids are recognised as important health promoting ingredients of the human diet. Some have antioxidant properties, and are supposedly beneficial in preventing cancer, cardiac disease, and eye diseases (Krinsky et al. 2004). Lutein and zeaxanthin are thought to be important in the human diet to prevent age-related macular degeneration (AMD; Moeller et al. 2006; Seddon et al. 1994; Snodderly 1995). Lutein and zeaxanthin are components of the macula lutea in the human eye (Handelman et al. 1988), protecting the retina against damaging irradiation, but they have to be replenished constantly. As humans can not produce lutein and zeaxanthin themselves they have to be consumed by eating carotenoid-rich plant products. Lutein is present in high amounts in dark green leafy vegetables such as spinach and kale. Zeaxanthin, however, is less abundant in most vegetables (Sommerburg et al. 1998).

In tetraploid potato lutein is present in relatively large amounts, whereas zeaxanthin is present in lower amounts (Breithaupt and Bamedi 2002; Nesterenko and Sink 2003). However, some Solanum species closely related to S. tuberosum have high zeaxanthin content (Andre et al. 2007). These are known as ‘Papa Amarilla’ because of their deep yellow or orange-fleshed tubers. These landraces grown by indigenous farmers in the Andean region belong to the diploid species S. stenotomum, S. goniocalyx and S. phureja (Brown et al. 2007; Burgos et al. 2009). Brown et al. (2007) and Brown (2008) observed a relationship between ploidy level and total carotenoid content in 38 native South American cultivars. Significantly higher mean levels of total carotenoids were observed in diploid cultivars compared with tetraploid cultivars. Morris et al. (2004) describe a diploid high carotenoid-accumulating S. phureja accession (DB375\1, or ‘Inca Dawn’) that predominantly contains zeaxanthin, but has a lower yield than tetraploid S. tuberosum cultivars (Bradshaw and Ramsay 2005). Kobayashi et al. (2008) bred a diploid potato variety with orange flesh and very high zeaxanthin content. This variety was derived from S. phureja. It would be interesting to obtain high-yielding orange-fleshed tetraploid potato cultivars to aid in the recommended daily uptake of zeaxanthin, as potatoes and potato products constitute a considerable part of the human diet in the Western world.

Yellow flesh colour in potato is mainly dependent on the presence of a dominant allele (Fruwirth 1912) at the Y (Yellow) locus. The Y locus has been mapped on chromosome 3 of potato by Bonierbale et al. (1988). The most likely candidate for the gene involved in yellow flesh colour is beta-carotene hydroxylase (abbreviated to Bch or Chy2; Brown et al. 2006). This gene has been mapped at the same position as the Y locus (Thorup et al. 2000).

Until now, the gene(s) responsible for the orange tuber flesh colour in diploid Solanum species are unknown. Brown et al. (1993) observed progeny with orange flesh colour and high levels of zeaxanthin in a hybrid population of S. phureja-S. stenotomum. They suggested that the orange phenotype was caused by a dominant Or allele at or close to the Y locus on chromosome 3 of potato. However, this was not corroborated by later research, as Brown (2008) reported. Lack of transmissibility outside the immediate ‘Papa Amarilla’ gene pool negated the hypothesis that the expression of Or was consistent with a strong dominant monogenic inheritance. In cauliflower an Or gene was cloned, responsible for orange-coloured curds (Lopez et al. 2008). This gene was found not to be involved in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, but to control chromoplast differentiation, resulting in the sequestering of large amounts of carotenoids.

This paper describes DNA polymorphisms among haplotypes of three candidate genes involved in the carotenoid pathway in monoploid, diploid and tetraploid potato genotypes, and explains the inheritance of yellow and orange potato tuber flesh colour.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

For sequence analyses DNA was used from five monoploid potato genotypes: 7322 (H7322 or AM79.7322, originally from G. Wenzel, Institüt für Genetik, Grünbach, Germany, see: De Vries et al. 1987; Hovenkamp-Hermelink et al. 1988), M5 and M38 (851-5 and 851-38, Uijtewaal 1987), M47 and M133 (1022 M-47 and 1022 M-133, Hoogkamp et al. 2000). DNA from 20 monoploid S. phureja and S. chacoense clones was obtained from Richard Veilleux (Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, see Lightbourn and Veilleux 2007). DNA was isolated from eleven diploid genotypes: C (USW5337.3, Hanneman and Peloquin 1967), E (77.2102.37, Jacobsen 1980), RH88-025-50 and RH90-038-21 (Park et al. 2005), RH89-039-16 and SH83-92-488 (Rouppe van der Voort et al. 1997; Van Os et al. 2006), 87.1024/2 and 87.1029/31 (Jacobsen et al. 1989), G254 (Uijtewaal et al. 1987), R5 (EJ92-6486-19, from cross 87.1024/2× EJ91-6104-19) and 413 (transformant of interdihaploid H2260; Binding et al. 1978; De Vries-Uijtewaal et al. 1989). Three diploid orange-fleshed genotypes were analysed: cultivars ‘Papa Pura’ and ‘Andean Sunrise’ (provided by Agrico Research BV), and S. phureja ‘Yema de Huevo’ (obtained from Enrique Ritter, Vitoria, Spain, see Ritter et al. 2008). Two diploid populations were analysed in which orange-fleshed progeny segregated: the C×E population (Jacobs et al. 1995) and the IvP92-030 population (cross G254 × SUH2293, from Ronald Hutten, Lab. of Plant Breeding, Wageningen University). Furthermore, orange-fleshed diploid genotype IvP01-84-19 from the cross 96-4622-20 × IvP92-027-9 (Ronald Hutten) was included. Additionally, a set of 225 tetraploid cultivars was used (D’hoop et al. 2008; D’hoop 2009). In this set no genotypes with orange-fleshed tubers were present. Flesh colour of the tetraploids was determined in a field experiment in 2006 (D’hoop 2009). Flesh colour values were on an ordinal scale ranging from 4 (=white) to 9 (=orange) according to the Dutch Catalogue of Potato Varieties (www.nivap.nl).

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA from the monoploid and diploid genotypes was isolated from leaf tissue according to the CTAB method from Rogers and Bendich (1988). DNA from the tetraploid cultivars was isolated according to Van der Beek et al. (1992).

PCR amplification and sequencing

Amplicons for sequencing were generated from 50 ng genomic DNA template. PCR amplifications were performed in 50 or 25 μl reactions using 1 u of Taq polymerase, 1× reaction buffer, 200 nM dNTP and 250 nM of each primer. Standard cycling conditions were: 4 min initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 55°C and 30 s to 1 min extension at 72°C. Reactions were finished by 7 min incubation at 72°C. For CAPS marker analysis 30 cycles were used. Most PCRs were performed with SuperTaq Polymerase buffer and enzyme (Applied Biosystems). PCR products were examined for quality on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. PCR products were directly sequenced on ABI377 or ABI3700 sequencers at Greenomics (Wageningen University and Research Centre) using the dideoxy chain-termination method and ABI PRISM Reaction Kit. One or both of the amplification primers were used as sequencing primers. For SNP analysis of the Chy2 gene primers CHY2ex4F (5′-CCATAGACCAAGAGAAGGACC-3′) and Beta-R822 (5′-GAAAGTAAGGCACGTTGGCAAT-3′) were used. For SNP analysis of the Lcye gene primers AWLCYe1 (5′-AAAAGATGCAATGCCATTCGAT-3′) and AWLCYe2 (5′-GAAATACTCGGGGTACTTGAAC-3′) were used. For SNP analysis of the Zep gene primers AWZEP9 (5′-GTGGTTCTTGAGAATGGACAAC-3′) and AWZEP10 (5′-CACCAGCTGGTTCATTGTAAAA-3′) were used. As CAPS marker for Chy2 the 308-bp CHY2ex4F + Beta-R822 PCR product was cleaved with AluI. The 163-bp fragment was indicative for the presence of Chy2 allele 3. As CAPS marker for Lcye the AWLCYe1 + AWLCYe2 PCR product was digested with SsiI, which distinguished allele 2 from alleles 1 and 3. By digesting the AWLCYe1 + AWLCYe2 PCR product with HpyCH4IV allele 1 could be distinguished from alleles 2 and 3.

SNP analysis and bioinformatics

PCR reactions included a mixture of templates reflecting the different alleles in DNA samples from heterozygous diploid and tetraploid genotypes. Trace files from directly sequenced PCR products were analysed for secondary peaks, indicative for SNPs, with the Vector NTI software package from Invitrogen. Homology searches were performed at the NCBI webpage (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the TGI webpage (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi/Blast/index.cgi), the SGN webpage (http://sgn.cornell.edu/), and the PGSC webpage (restricted access; http://bacregistry.potatogenome.net/pgscreg/main.py). To study possible effects of amino acid changes on functionality of the protein the programs SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant, see http://sift.jcvi.org/ [Ng and Henikoff 2006]) and PolyPhen (Polymorphism Phenotyping, see http://coot.embl.de/PolyPhen/) were used. Classification of the non-LTR retrotransposon sequence in Zep allele 1 was performed at http://www.girinst.org/RTphylogeny/RTclass1.

Genetic mapping and QTL analysis in the diploid C×E population

A C×E genetic map using 94 C×E progeny was made based on an earlier version of the map (Celis-Gamboa 2002) with additional SNP markers (Anithakumari et al. 2010) using mapping software Joinmap 4.0® (Van Ooijen 2006). QTL analysis of quantitative data was performed using the software package MapQTL® Version 5.0 (Van Ooijen 2004).

Cloning of Zep promoter sequence

The promoter sequence of Zep allele 1 was obtained by Genome Walking using the Universal GenomeWalker kit (Clontech) and the BD Advantage 2 PCR Enzyme System (BD Biosciences). DNA from diploid genotype R5 (homozygous for Zep allele 1) was used as template. Four libraries were made using DraI, EcoRV, StuI and ScaI enzymes. The first PCR was performed with primer AP1 and gene-specific primer AWZEPGW1 (5′-TTCTGTGGAACCTTCAAATCACCGTTA-3′). The nested PCR was performed with primer AP2 and gene-specific primer AWZEPGW2 (5′-GCCCATTTTCCAAGCTCCTACAAGGTA-3′). The DraI- and StuI-libraries yielded a 1.1 and 1.8-kb PCR fragment, respectively. The 1.8-kb PCR fragment of the StuI library was sequenced, and proved to contain a DraI restriction site at the expected position.

Cloning intron 1 of Zep allele 1

To obtain the intron 1 sequence of Zep allele 1 primers AWZEP25 (5′-CTGGCTGCATCACTGGTCAAAG-3′) and AWZEP20 (5′-TCATTCATAATTGTATCCTCCC-3′) were used. The Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche Applied Science) was used to obtain the 4.7-kb PCR fragment. This fragment was cloned into pGEM-Teasy (Promega). Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Promega Wizard Plus minipreps DNA Purification system. DNA from three independent colonies was first sequenced using the T7, AWZEP25 and AWZEP20 primers, and subsequently with primers designed on the obtained sequences.

Measurement of carotenoids

From 94 progeny of the diploid C×E population carotenoids were extracted and analysed by HPLC with photodiode array (PDA) detection, according to the protocol described by Bino et al. (2005). In short, 0.5 g FW of ground and frozen tuber material was extracted with methanol/chloroform/1 M NaCl in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4) in a ratio of 2.5:2:2.5 (v:v:v) containing 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). After centrifugation, the samples were re-extracted with 1 ml chloroform (+BHT). The chloroform fractions were combined, dried under a flow of N2 gas and taken up in ethyl acetate containing 0.1% BHT. Carotenoids present in the extracts were separated by HPLC using an YMC-Pack reverse-phase C30 column and analysed by PDA detection with wavelength range set from 240 to 700 nm. Eluting compounds were identified based on their absorbance spectra and co-elution with commercially available authentic standards (neoxanthin, violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, ε-carotene, α-carotene, β-carotene, ζ-carotene, δ-carotene, prolycopene and all-trans lycopene. Limit of detection was about 5 μg per 100 g FW and technical variation (6 independent extractions and analyses of the same tuber powder) was less than 8%.

In addition to the measurement of individual carotenoids yellowness of the tuber flesh of the 94 C×E progeny was determined by spectrophotometry. The same carotenoid extraction used for HPLC analysis was measured with a Perkin Elmer UV/MS Spectrometer Lambda 10. The peak area from 380 to 515 nm was determined with the UV WinLab software from Perkin Elmer using the 525–580 nm measurement as baseline. The peak area in the yellow spectrum is referred to as absorbance between 380 and 515 nm.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA of 23 selected genotypes of the C×E population was isolated from mature tubers as described by Bachem et al. (1998). mRNA was purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit from Bio-Rad. Relative expression level of the Zep locus was determined by real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) on an iQ detection system (Bio-Rad) according to the Bio-rad iQ SYBR Green Supermix protocol. The primer sequences used for the analysis were StZEP_RT_F (5′-AAGTGCCGAGTCAGGAAGCC-3′) from exon 7 and StZEP_RT_R (5′-CAAGTCCGACGCCAAGATAAGC-3′) from exon 8. Potato elongation factor 1-α (EF1α) primers were used for relative quantification (Nicot et al. 2005). Relative quantification of the target RNA expression level was performed using Bio-rad iQ5 analysis program.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers HM013963 (potato Chy2 genomic sequence), HM013964 (potato Zep allele 1 genomic sequence) and HM013965 (potato Zep allele 2 genomic sequence). The potato Lcye genomic sequence is available in the Third Party Annotation Section of the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession number TPA: BK007065. The sequence of the PCR fragment obtained with primers AWLCYe1 and AWLCYe2 for allele 4 is available under accession number HM011105. Accession numbers for the BAC sequences are AC216345 (tomato BAC LE_HBa-11D12), AC238165 (potato BAC RH091F11), AC238104 (RH071N14), AC238398 (RH196E12), AC238240 (RH132J19) and AC215383 (tomato BAC C02HBa0104A12).

Results

Allelic variation for the beta-carotene hydoxylase2 gene (Chy2)

We started our investigation of the genetic requirements for orange potato tuber flesh by analysing whether orange-fleshed diploid potato genotypes contain different Chy2 alleles than white- or yellow-fleshed tetraploid cultivars. Chy2 was observed to be an important gene involved in tuber flesh colour in two separate studies performed on diploid populations (Brown et al. 2006; Kloosterman et al. 2010). RNA expression analysis using the 44 K POCI array (Kloosterman et al. 2008) resulted in the identification of an eQTL for yellow tuber flesh colour on potato chromosome 3 at a similar position as the Chy2 gene. Further analysis indicated that in the diploid C×E population the parent C-specific allele of the Chy2 gene was correlated with yellow flesh. This allele shows higher expression than the other two alleles segregating in the C×E population (Kloosterman et al. 2010). Goo et al. (2009) also observed a higher expression level of Chy2 associated with yellow flesh colour in a small number of potato cultivars.

In order to study allelic variation for the Chy2 gene in tetraploids we first determined the complete genomic sequence of the Chy2 allele in monohaploid (2n = x = 12) potato genotype 7322, as only mRNA and EST sequences were known for the potato Chy2 gene. The obtained 2,255-bp genomic sequence (Fig. 1) contains seven exons. Next, we performed direct sequencing analyses of a PCR fragment obtained with primers CHY2ex4F and Beta-R822, spanning exon 4, intron 4 and exon 5 of the Chy2 gene (Fig. 1). We used DNA of four additional potato monoploids, 20 S. phureja and S. chacoense monoploids, and 11 diploids. From these sequences in total eight different haplotypes could be determined (Supplemental Table S1; alleles 1–7 and 11).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic sequence of the potato beta-carotene hydroxylase 2 (Chy2) gene. The 2,255-bp of allele 1 of monoploid 7322 is shown. The PCR product analysed for the presence of SNPs is indicated

We observed a correlation between presence of a single haplotype—allele 3—and yellow flesh colour in a number of diploids. Heterozygosity for allele 3 is sufficient for yellow flesh colour, indicating this is a dominant allele. This observation corroborates the results of genetic analysis of the Chy2 (or Bch) gene by Brown et al. (2006). Furthermore, we observed that SNP 142C distinguished Chy2 allele 3 from all other haplotypes. As this SNP is unique to one haplotype it is a so-called ‘haplotype tag SNP’ (Johnson et al. 2001), hereafter referred to as ‘tag SNP’. Allele 3 is most probably identical to the dominant allele B described by Brown et al. (2006), because sequencing of allele 3 showed the presence of allele B-specific primer sequence YellowF1. This allele is considered to be the dominant Y allele at the Yellow (Y) locus first postulated by Fruwirth (1912).

Next, we performed a SNP analysis on the DNA of a set of 225 tetraploid potato cultivars (D’hoop 2009). This set aims to represent the most important potato cultivars of the last 150 years in terms of acreage and/or value as progenitor, mainly from Europe, but also from the USA, Canada, and some other continents. The same PCR fragment that was analysed for the monoploids and diploids was amplified in the tetraploids. Direct sequencing was performed, which resulted in the discovery of three additional alleles (Supplemental Table S1; alleles 8, 9, 10). The dosage of SNP 142C (i.e. allele 3) was determined from the sequence trace files. Dosage of allele 3 could also be estimated by using a CAPS marker assay (Supplemental Fig. S1), in which of all Chy2 alleles only allele 3 yielded a 163-bp fragment. The allele 3 dosage was related to the flesh colour value (Table 1). A flesh colour value of 5.5 or lower represents white flesh, whereas a flesh colour value higher than 5.5 indicates yellow flesh. As is shown in Table 1 presence or absence of Chy2 allele 3 is correlated with flesh colour: the group of cultivars lacking allele 3 have a mean value of 5.1 (white flesh), whereas the cultivars simplex, duplex, triplex or quadruplex for allele 3 have a mean value higher than 6 (yellow flesh). The data suggest a dosage effect of allele 3 as the quadruplex genotypes have the highest mean value. However, this group consists of only two genotypes. Although there is a clear correlation between presence of Chy2 allele 3 and yellow flesh, the intensity of the yellow flesh colour shows considerable variation within the different dosage groups, as shown in Fig. 2. This was also observed by Brown et al. (2006).

Table 1.

Relation between the number of Chy2 alleles and tuber flesh colour

| Chy2 allele 3 dosage | Mean tuber flesh colour value | Flesh colour | Number of genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0× (nulliplex) | 5.0 | White | 69 |

| 1× (simplex) | 6.3 | Yellow | 71 |

| 2× (duplex) | 6.5 | Yellow | 46 |

| 3× (triplex) | 6.6 | Yellow | 11 |

| 4× (quadruplex) | 7.4 | Yellow | 2 |

Fig. 2.

Variation in flesh colour value in classes of tetraploid potato genotypes with 0×, 1×, 2×, 3×, and 4× Chy2 allele 3. Flesh colour value equal to or below 5.5 is considered to correspond to white flesh, values above 5.5 are indicative of yellow flesh

To evaluate if Chy2 alleles other than allele 3 have a (small) influence on flesh colour the Chy2 allele composition was determined for 199 of the 225 tetraploid potato genotypes by analyzing tag SNPs. Large differences in allele frequency were observed. Four major alleles were observed: alleles 5 (35%), 3 (26%), 1 (20%) and 2 (13%). Four minor alleles were observed: alleles 6 (4%), 10 (2%), 8 (0.8%) and 9 (0.3%). Alleles 4, 7 and 11 were not observed in the tetraploid S. tuberosum cultivars and seem to be restricted to diploid germplasm. Minor allele 6 has been present in the Solanum tuberosum gene pool for a long time, as it is observed in nine cultivars released before 1900. Minor alleles 8, 9 and 10 seem to be novelties in the S. tuberosum gene pool, because these alleles are only present in cultivars released to the market after 1960, directly descending from backcross introgression material with late blight or cyst nematode resistance. For example, allele 10, containing an indel (1-nt deletion) in the analysed PCR fragment, is present in a number of cultivars derived from VTN 62-33-3 (1962), suggesting that this might be an S. vernei allele (see Kort et al. 1972).

None of the alleles 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 9 or 10 were related to yellow flesh colour. Furthermore, none of these alleles influenced flesh colour value within the white/creamy flesh colour class, nor within the yellow flesh colour class. Thus, the variation in intensity of yellow flesh colour can not be explained by the composition of the other Chy2 alleles in the simplex, duplex and triplex allele 3 groups.

Chy2 allele composition was determined in diploid orange-fleshed genotypes ‘Papa Pura’, ‘Andean Sunrise’, ‘Yema de Huevo’, IvP92-030-11 and IvP01-84-19. Although they all contained one Chy2 allele 3, they differed in the other allele, and no novel allele absent from the tetraploid gene pool was discovered. Therefore, we concluded that other genes—possibly involved in the carotenoid biosynthetis pathway—influenced the intensity of the yellow flesh colour.

Allelic variation for the lycopene epsilon cyclase gene (Lcye)

The lycopene epsilon cyclase gene product is required for the synthesis of α-carotene, the precursor of lutein (see Tanaka et al. 2008). Silencing of the Lcye gene resulted in a significant increase in the beta-carotenoids (Diretto et al. 2006). An increase in the level of beta-carotene and zeaxanthin is expected to result in a darker yellow flesh.

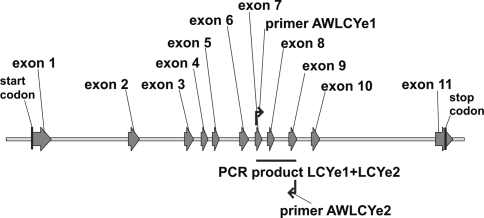

To be able to analyse allelic variation for the Lcye gene in potato we needed information on the genomic sequence of the Lcye gene. Tomato BAC LE_HBa-11D12 (from chromosome 12) contains the tomato homologue of Lcye. Using this sequence four potato BAC clones from diploid genotype RH89-039-16 containing the potato Lcye homologue were retrieved from the Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium (PGSC) database: RH091F11, RH071N14, RH196E12 and RH132J19. The 7,000-bp genomic sequence of the Lcye gene contains 11 exons (Fig. 3). Primers AWLCYe1 and AWLCYe2 were designed, which amplified a fragment spanning exon 7 to exon 9 of the Lcye genomic sequence (Fig. 3). PCR fragments from the monoploids and diploids were directly sequenced, and 5 different alleles could be observed (Supplemental Table S2). Potato BACs RH091F11 and RH071N14 contained allele 4, whereas two BACs from the homologous chromosome (RH196E12-4 and RH132J19-7) contained allele 1 of diploid genotype RH89-039-16.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the genomic sequence of the potato lycopene epsilon cyclase (Lcye) gene. A 7,000-bp sequence from BAC RH091F11 from diploid genotype RH89-039-16 is shown. The PCR product analysed for the presence of SNPs is indicated

Two alleles (allele 2 and allele 5) contain a T at SNP position 545. This nucleotide causes a change of amino acid 401 of the Lcye protein from S (serine) to F (phenylalanine). To analyse the effect of this amino acid change we consulted two software programs: SIFT and PolyPhen. According to the SIFT program an F at position 401 is not tolerated, and according to the PolyPhen program it is possibly damaging. Diploid genotype C contains Lcye alleles 2 and 3, while genotype E contains Lcye alleles 1 and 2. Thus, C and E have Lcye allele 2 in common. Therefore, 25% of the progeny of a cross between these genotypes is expected to be homozygous for allele 2. Some of the progeny of the C×E cross have a much higher flesh colour value than the yellow parent C, i.e. some have orange flesh. To investigate whether homozygosity of Lcye allele 2 leads to a difference in flesh colour 94 C×E progeny plants were analysed for their Lcye allele composition by CAPS marker assays. Data were used to localize the Lcye gene on the C×E linkage map. As expected, Lcye mapped to a position on chromosome 12 close to the STM2028 microsatellite marker and the SUS4 gene at the Southern distal end of the chromosome.

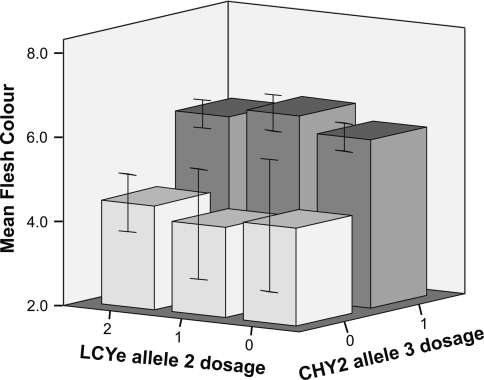

Dosage of Lcye allele 2 and dosage of Chy2 allele 3 were plotted against flesh colour value (Fig. 4). This figure shows a strong correlation between presence of Chy2 allele 3 and a high value for flesh colour, whereas dosage of Lcye allele 2 does not seem to have an influence on flesh colour. This suggests that a different gene than Lcye must have an influence on intensity of yellow flesh colour.

Fig. 4.

Relation between Chy2 allele 3 dosage, Lcye allele 2 dosage, and phenotypic value of tuber flesh colour in the diploid C×E mapping population. Error bars ±2 SE

Allelic variation for the zeaxanthin epoxidase gene (Zep)

Another candidate gene for orange tuber flesh in potato is the Zep gene. Zep is involved in the conversion of zeaxanthin into antheraxanthin, and in the conversion of antheraxanthin into violaxanthin (Tanaka et al. 2008). Silencing of the Zep gene in potato resulted in transformants with higher zeaxanthin levels, and increased total carotenoid contents (Römer et al. 2002). Similarly, Morris et al. (2004) observed an inversed trend between the level of Zep transcript and tuber carotenoid content in a range of potato germplasm.

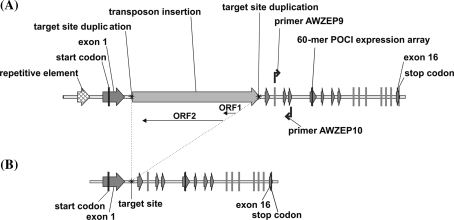

A genomic sequence of the tomato Zep gene was found to be present in BAC C02HBa0104A12.1, anchored to tomato chromosome 2 (Supplemental Fig. S2), which is in agreement with the map position of the pepper (Capsicum) Zep gene on chromosome 2 (Thorup et al. 2000). Using the tomato BAC sequence and potato Zep cDNA sequence DQ206629 primers were designed allowing amplification and sequencing of the complete potato Zep gene (Fig. 5). Using primer combination AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 five different alleles could be distinguished in the monoploid and diploid S. tuberosum genotypes (Supplemental Table S3, alleles 1–5). The AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 PCR product, spanning exon 3 to exon 5, showed the presence of a relatively large indel in intron 4. In Zep allele 1 a sequence of 49 bp is absent, which is present in alleles 2, 3, 4 and 5. Therefore, Zep allele 1 could be distinguished from the other alleles by gel electrophoresis. The AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 PCR product of allele 1 is 535 bp long, whereas this PCR product is 584 bp for the other alleles (Supplemental Fig. S3b).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the genomic sequence of the potato zeaxanthin epoxidase (Zep) gene. a 11,000-bp sequence of allele 1, including promoter and coding region; b 6,008-bp sequence of allele 2, including promoter and coding region

Recessive inheritance of orange tuber flesh

Zep allele composition was determined in diploid orange-fleshed genotypes ‘Papa Pura’, ‘Andean Sunrise’, ‘Yema de Huevo’, IvP92-030-11 and IvP01-84-19. All five genotypes proved to be homozygous for Zep allele 1. As these five genotypes are not closely related to each other this suggests the involvement of Zep allele 1 in the orange flesh phenotype.

Genetic evidence for the involvement of Zep allele 1 in orange flesh colour was obtained from cosegregation in the diploid IvP92-030 population (progeny of the cross between diploids G254 and SUH2293). This population was analysed for both Chy2 and Zep allele compositions (Supplemental Fig. S3). Parent G254 contained CHY2 alleles 2 and 6, while parent SUH2293 contained Chy2 alleles 3 and 5. Progeny with allele combinations 2 + 3, 2 + 5, 3 + 6 and 5 + 6 were observed (Supplemental Fig. S3a). Both parents G254 and SUH2293 contained Zep alleles 1 and 2. Progeny with allele combinations 1 + 1, 1 + 2 and 2 + 2 were obtained in numbers compatible with the expected 1:2:1 ratio (Supplemental Fig. S3b). Only progeny plants IvP92-030-9 and IvP92-030-11, containing Chy2 allele 3 and homozygous for Zep allele 1, showed the orange-fleshed phenotype. This suggests a model in which presence of dominant Chy2 allele 3 and homozygosity for recessive Zep allele 1 are required to obtain an orange-fleshed potato.

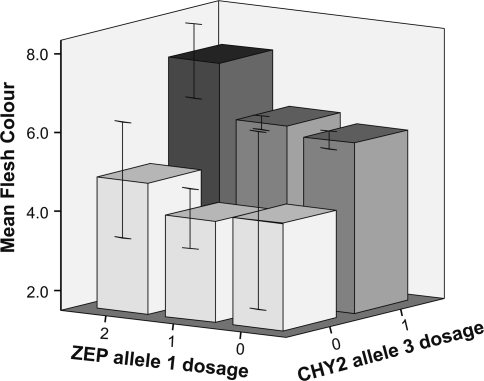

To investigate this further progeny of the C×E cross was analysed for Zep allele composition. Both C and E parents contain Zep alleles 1 and 2. A CAPS marker was developed to easily distinguish both Zep alleles. For this, PCR product AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 was digested with the enzyme Hin6I. The PCR product of Zep allele 1 remained undigested, whereas the PCR product of allele 2 was digested into fragments of 439 and 145 bp. Ninety-four C×E progeny were analysed with this CAPS marker. The Zep gene was mapped in the C×E population on chromosome 2 in a similar position as the one on tomato chromosome 2 (Supplemental Fig. S2). Dosage of Zep allele 1 and dosage of Chy2 allele 3 were related to flesh colour value (Fig. 6). This figure shows that homozygosity of Zep allele 1 in combination with presence of Chy2 allele 3 results in a significantly higher mean flesh colour value. A QTL analysis for absorbance in the yellow spectrum in the C×E population resulted in a highly significant QTL on chromosome 2, on the same position as the Zep gene (B. Kloosterman, pers.comm.).

Fig. 6.

Relation between Chy2 allele 3 dosage, Zep allele 1 dosage, and flesh colour value in the diploid C×E population. Error bars ±2 SE

Role of Zep allele 1 on zeaxanthin levels

For 88 C×E progeny the amounts of individual carotenoids were determined. A small number of progeny (10 genotypes) proved to contain relatively high levels of zeaxanthin (>250 μg per 100 g fresh weight). These progeny invariably contained Chy2 allele 3 and were homozygous for Zep allele 1. In Fig. 7 the relation between zeaxanthin content and absorbance in the yellow spectrum is displayed for four classes of genotypes. Y or y represent the dominant or recessive Chy2 allele, respectively, and Z or z represent the dominant or recessive Zep allele. Y is Chy2 allele 3, and z is Zep allele 1. This figure shows that zeaxanthin only accumulates in considerable amounts in genotypes homozygous for Zep allele 1 (zz, filled symbols). When dominant Chy2 allele 3 is present (Yyzz) the zeaxanthin level is higher than when this allele is absent (yyzz). These results suggest that orange flesh colour indicates the presence of a zeaxanthin level of more than 250 μg/100 g fresh weight tuber.

Fig. 7.

Relation between zeaxanthin content and absorbance in the yellow spectrum in the diploid C×E population. Zeaxanthin content in μg/100 g fresh weight. Four genotypic classes are indicated, with Y/y respresenting Chy2 alleles, and Z/z representing Zep alleles. Y is dominant Chy2 allele 3; z is recessive Zep allele 1

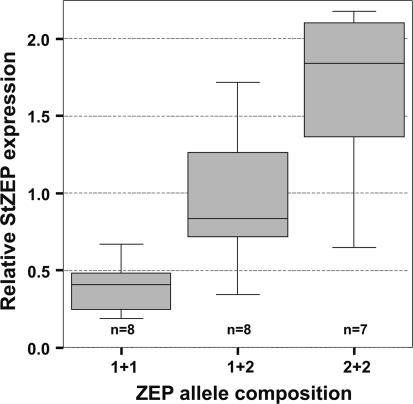

ZEP allele 1 is expressed at a low level

Expression analysis using the 44 k POCI array indicated that tuber RNA from parents C and E showed a similar level of hybridization to the Zep-derived 60-mer oligo (B. Kloosterman, pers. comm.). Both parents are heterozygous for Zep, containing alleles 1 and 2. Tuber RNA from C×E progeny homozygous for Zep allele 2 showed a higher level of hybridization with the Zep oligo than both parents, whereas tuber RNA from C×E progeny homozygous for Zep allele 1 showed a lower level of hybridization than both parents. This may reflect a difference in homology of the Zep alleles with the oligo. It was found that the 60-mer oligo on the POCI array (Kloosterman et al. 2008) is identical to a sequence in exon 6 of Zep allele 1, while there is one mismatch with the sequence in Zep allele 2. If the mismatch would result in a lower level of hybridization it would be expected that RNA from progeny homozygous for Zep allele 2 would show a lower level of hybridization. However, the opposite was observed. Therefore, the array results suggest that Zep allele 2 is expressed at a higher level than Zep allele 1. This was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 8): diploid C×E progeny homozygous for ZEP allele 1 showed a significantly lower level of expression than C×E progeny homozygous for ZEP allele 2. Heterozygous progeny displayed an intermediate level of expression. A similar observation was made by Morris et al. (2004) who found that high carotenoid-accumulating diploid S. phureja genotype DB375\1 (later renamed cultivar ‘Inca Dawn’) showed low expression of the Zep gene. They observed an inverse relationship between zeaxanthin transcript level and total carotenoid content in a range of potato germplasm.

Fig. 8.

Quantitative RT-PCR of Zep alleles. Relative expression level of the Zep gene for C×E progeny homozygous for allele 1, heterozygous (allele 1 + allele 2), or homozygous for allele 2. Zep allele 1 results in a lower expression level than Zep allele 2

To investigate the reason for the lower expression level of Zep allele 1 a 1.8-kb fragment containing the promoter of this allele was obtained by Genome Walking and was sequenced. A BLASTN analysis revealed that the 5’part of this sequence contained a repetitive element (present on several chromosomes of S. tuberosum and S. lycopersicum). An analysis of cis-regulatory elements showed that the ZEP promoter contains light-regulated, phytochrome-regulated, and water stress-regulated boxes, as well as hypo-osmolarity-responsive and sugar-repression elements. Subsequently, this sequence was compared with the promoter sequence of Zep allele 2 (as present in monoploid M133), see Supplemental Fig. S4. Although a number of SNPs was observed, no obvious differences were found that could explain the different expression levels.

Next, the complete genomic sequence, including all exons and introns, was determined for both Zep alleles 1 and 2 (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. S4). The exon sequences were translated into protein sequences and aligned to each other (Supplemental Fig. S5). Although a number of amino acid changes were observed, especially in the first exon, no obvious amino acid change was found predicting a non-functioning enzyme according to SIFT. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of Zep alleles 1 and 2 with Zep protein sequences of other Solanaceous species (Supplemental Fig. S6) indicated that the differences in amino acids between Zep alleles 1 and 2 mostly occurred in the least conserved regions.

However, we observed a large difference in size in the first intron. Intron 1 in Zep allele 2 is 389 bp in size, comparable with the 438-bp intron 1 of the tomato Zep genomic sequence. In contrast, the size of intron 1 in Zep allele 1 is 4,509 bp. By comparing the sequences of the first intron of Zep alleles 1 and 2 we observed that a 4,102-bp non-LTR retrotransposon-like sequence had integrated in intron 1 of allele 1, causing a target site duplication of 18 bp. Analysis of this sequence showed the presence of two open reading frames (ORFs) in the DNA strand antisense relative to the promoter (Fig. 5a). The first ORF contains an endonuclease/ exonuclease domain. The second ORF contains a non-LTR retrotransposon reverse transcriptase domain. Alignment of the reverse transcriptase domain of the retrotransposon in intron 1 in Zep allele 1 (ZEPphur) with the domains of LINE-1 like retrotransposons from other species is shown in Supplemental Fig. S7. Analysis of the protein sequence of ORF2 at the non-LTR retrotransposon classification webpage (Kapitonov et al. 2009) revealed that the retrotransposon in Zep allele 1 belongs to the RTE clade, and is closely related to the RTE1_ZM retrotransposon from Zea mays (Obukhanych and Jurka 2007). A BLASTN search of this retrotransposon sequence using the available potato genomic sequences at the PGSC webpage revealed homologous sequences on all 12 potato chromosomes, except chromosome 7. A similar search at the NCBI webpage using the high throughput genomic sequences (HTGS) database showed the presence of homologous retrotransposon sequences in several Solanaceous species, e.g. Solanum, Nicotiana, Petunia and Capsicum species. A BLASTN search using EST databases revealed that transcription of sequences homologous to the ZEPphur retrotransposon occurs.

Occurrence of ZEP allele 1 in the tetraploid potato gene pool

To determine the frequency of Zep allele 1 in the tetraploid potato gene pool PCR with primers AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 was performed using DNA from a set of 221 tetraploid potato cultivars (D’hoop et al. 2008) and some additional cultivars. From 230 genotypes that yielded a PCR product only 5 contained Zep allele 1, all in simplex. These were genotypes Black 1256, Prevalent (descendent from Black 1256), Producent (descendent from Prevalent), Lady Claire and Pallas (both descendents from S. phureja PHUR 71-464-7). This indicates that Zep allele 1 is a rare allele in the tetraploid potato gene pool (frequency 0.5%).

Zep allele composition was determined in 111 tetraploid potato genotypes not containing Zep allele 1, by sequencing the AWZEP9 + AWZEP10 PCR product. Four additional alleles were observed besides the alleles present in the monoploid and diploid genotypes (Supplemental Table S3). Alleles 2 (36%), 3 (25%), 4 (14%) and 5 (20%) were major alleles, whereas alleles 6 (0.9%), 7 (0.5%), 8 (1.6%) and 9 (1.6 %) were minor alleles. The minor alleles 6–9 are all present in tetraploid potato cultivars released after 1960. Alleles 3–9 had an intron 1 of similar size as intron 1 in allele 2. Therefore none of these alleles contained the transposon insertion present in allele 1.

Discussion

We conclude that homozygosity for Zep allele 1 in the presence of dominant Chy2 allele 3 is causing the orange flesh colour phenotype, due to high levels of zeaxanthin. Furthermore, we conclude that Zep allele 1 is a recessive allele. The accumulation of zeaxanthin does not seem to be caused by impaired function of the Zep protein resulting from amino acid changes, as we observed no obvious amino acid changes in allele 1 compared with allele 2. Rather, the accumulation of zeaxanthin seems to result from a lower steady state mRNA level of Zep, as determined by qRT-PCR.

Morris et al. (2004) observed an inverse relationship between the Zep transcript level and the total tuber carotenoid content. They investigated transcript level by quantitative RT-PCR using primers designed on the basis of tomato Zep cDNA sequence Z83835. However, DNA polymorphisms between potato and tomato can easily distort such analyses. Their forward primer contains an A at position 18 instead of G, as present in potato Zep cDNA DQ206629 and potato EST CK278242. We observed only G at this position in our Zep alleles, including allele 1, indicating a SNP in Zep sequences between tomato and potato close to the 3’ end of the forward primer. This mismatch may have a considerable influence on overall level of amplification in the RT-PCR experiment. We performed qRT-PCR on a diploid population segregating for Zep alleles 1 and 2, using primers without mismatches, and observed a clear difference in expression levels between genotypes homozygous for allele 1, heterozygous (allele 1 + 2) and homozygous for allele 2.

A small number of SNPs was observed in the promoter sequence of allele 1 compared with the sequence of allele 2, which may explain the difference in expression level between the two alleles. However, we think it is more plausible that the difference in expression level is caused by the large retrotransposon insertion in the first intron of allele 1. This large insertion may cause inefficient splicing of the pre-mRNA into mature mRNA, or alternative splicing caused by cryptic splice sites. Hanson (1989) reported that efficient intron splicing in plants may be constrained by intron length. Ohmori et al. (2008) reported that integration of a transposon in intron 4 of rice gene DL resulted in reduced expression of the gene. Similarly, Gazzani et al. (2003) and Michaels et al. (2003) observed that weak alleles of the Arabidopsis thaliana FLC gene showing reduced expression contained a transposon in the first functional intron. A lower expression level of the zeaxanthin epoxidase gene results in the accumulation of zeaxanthin, at the expense of antheraxanthin, violaxanthin and neoxanthin (Tanaka et al. 2008). As zeaxanthin is relatively orange coloured (depending on concentration and milieu), while antheraxanthin, violaxanthin and neoxanthin are (light) yellow, this explains the orange flesh phenotype of the potato genotypes homozygous for Zep allele 1 (and containing Chy2 allele 3).

Potato genotypes homozygous for Zep allele 1 do not show the wilty phenotype as observed in Arabidopsis, Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and tomato Zep mutants (Duckham et al. 1991; Galpaz et al. 2008; Marin et al. 1996), in which synthesis of plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA), a downstream metabolite of the carotenoid pathway, is compromised. Therefore, we conclude that the reduced expression of Zep allele 1 does not result in complete absence of ABA.

Römer et al. (2002) achieved increased zeaxanthin levels in potato tubers by genetic engineering. However, consumer acceptance of GMO cultivars is very low. Use of the natural variant Zep allele 1 allows classical breeding for orange-fleshed potato. Zep allele 1 probably is an S. phureja Zep allele, as it is almost absent in the S. tuberosum gene pool, and only present in a few tetraploid potato genotypes with S. phureja in their ancestry. This means that breeding of a tetraploid potato cultivar with orange tuber flesh (with high zeaxanthin content) is a challenging task.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Richard Veilleux for kindly sending us DNA of 20 monoploid S. phureja/S. chacoense monoploids, Dr. Enrique Ritter for providing us with small tubers of S. phureja ‘Yema de Huevo’, and Agrico Research B.V. for sending us tubers of ‘Papa Pura’ and ‘Andean Sunrise’. We thank Dr. Ric de Vos of PRI, Wageningen, for the carotenoid analysis. We thank STW for financial support of A.M.A. Wolters and J.G.A.M.L. Uitdewilligen (grant 07926), and the EU-SOL project (PL 016214-2 EU-SOL) for financial support of B.A. Kloosterman.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- Chy2

Beta-carotene hydroxylase 2

- Lcye

lycopene epsilon cyclase

- Zep

Zeaxanthin epoxidase

- AMD

Age-related macular degeneration

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait locus

- POCI

Potato oligo chip initiative

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- CAPS

Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence

- BAC

Bacterial artificial chromosome

- PGSC

Potato genome sequencing consortium

- SIFT

Sorting intolerant from tolerant

- PolyPhen

Polymorphism phenotyping

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- LTR

Long terminal repeat

References

- Andre CM, Oufir M, Guignard C, Hoffmann L, Hausman JF, Evers D, Larondelle Y. Antioxidant profiling of native Andean potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum L.) reveals cultivars with high levels of β-carotene, α-tocopherol, chlorogenic acid, and petanin. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:10839–10849. doi: 10.1021/jf0726583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anithakumari AM, Tang J, van Eck HJ, Visser RGF, Leunissen JAM, Vosman B, van der Linden CG. A pipeline for high throughput detection and mapping of SNPs from EST databases. Mol Breeding. 2010;26:65–75. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachem CWB, Oomen RJFJ, Visser RGF. Transcript imaging with cDNA-AFLP: a step-by-step protocol. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1998;16:157–173. doi: 10.1023/A:1007468801806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binding H, Nehls R, Schieder O, Sopory SK, Wenzel G. Regeneration of mesophyll protoplasts isolated from dihaploid clones of Solanum tuberosum. Physiol Plant. 1978;43:52–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1978.tb01565.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bino RJ, de Vos CHR, Lieberman M, Hall RD, Bovy A, Jonker HH, Tikunov Y, Lommen A, Moco S, Levin I. The light-hyperresponsive high pigment-2dg mutation of tomato: alterations in the fruit metabolome. New Phytol. 2005;166:427–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonierbale MW, Plaisted RL, Tanksley SD. RFLP maps based on a common set of clones reveal modes of chromosomal evolution in potato and tomato. Genetics. 1988;120:1095–1103. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.4.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JE, Ramsay G. Utilisation of the commonwealth potato collection in potato breeding. Euphytica. 2005;146:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-3881-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt DE, Bamedi A. Carotenoids and carotenoid esters in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.): new insights into an ancient vegetable. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7171–7181. doi: 10.1021/jf0257953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR. Breeding for phytonutrient enhancement of potato. Am J Pot Res. 2008;85:298–307. doi: 10.1007/s12230-008-9028-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Edwards CG, Yang CP, Dean BB. Orange flesh trait in potato: Inheritance and carotenoid content. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1993;118:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Kim TS, Ganga Z, Haynes K, De Jong D, Jahn M, Paran I, De Jong W. Segregation of total carotenoid in high level potato germplasm and its relationship to beta-carotene hydroxylase polymorphism. Am J Potato Res. 2006;83:365–372. doi: 10.1007/BF02872013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Culley D, Bonierbale M, Amorós W. Anthocyanin, carotenoid content, and antioxidant values in native South American potato cultivars. HortScience. 2007;42:1733–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos G, Salas E, Amoros W, Auqui M, Muñoa L, Kimura M, Bonierbale M. Total and individual carotenoid profiles in Solanum phureja of cultivated potatoes: I. Concentrations and relationships as determined by spectrophotometry and HPLC. J Food Compos Anal. 2009;22:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2008.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celis-Gamboa BC (2002) Life cycle of the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.): from crop physiology to genetics. Dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- D’hoop BB (2009) Association mapping in tetraploid potato. Dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- D’hoop BB, Paulo MJ, Mank RA, van Eck HJ, van Eeuwijk FA. Association mapping of quality traits in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Euphytica. 2008;161:47–60. doi: 10.1007/s10681-007-9565-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries SE, Ferwerda MA, Loonen AEHM, Pijnacker LP, Feenstra WJ. Chromosomes in somatic hybrids between Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and a monoploid potato. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;75:170–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00249160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries-Uijtewaal E, Gilissen LJW, Flipse E, Sree Ramulu K, Stiekema WJ, de Groot B. Fate of introduced genetic markers in transformed root clones and regenerated plants of monohaploid and diploid potato genotypes. Theor Appl Genet. 1989;78:185–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00288798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diretto G, Tavazza R, Welsch R, Pizzichini D, Mourgues V, Beyer P, Giuliano G. Metabolic engineering of potato tuber carotenoids through tuber-specific silencing of lycopene epsilon cyclase. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckham SC, Linforth RST, Taylor IB. Abscisic-acid-deficient mutants at the aba gene locus of Arabidopsis thaliana are impaired in the epoxidation of zeaxanthin. Plant Cell Environ. 1991;14:601–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1991.tb01531.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fruwirth C. Zur Züchtung der Kartoffel. Deutsche Landwirtschaftliche Presse. 1912;39(551–552):565–567. [Google Scholar]

- Galpaz N, Wang Q, Menda N, Zamir D, Hirschberg J. Abscisic acid deficiency in the tomato mutant high-pigment 3 leading to increased plastid number and higher fruit lycopene content. Plant J. 2008;53:717–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzani S, Gendall AR, Lister C, Dean C. Analysis of the molecular basis of flowering time variation in Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1107–1114. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo YM, Kim TW, Ha SH, Back KW, Bae JM, Shin YW, Lee CH, Ahn MJ, Lee SW. Expression profiles of genes involved in the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in yellow-fleshed potato cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.) from South Korea. J Plant Biol. 2009;52:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s12374-008-9003-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handelman GJ, Dratz EA, Reay CC, van Kuijk FJGM. Carotenoids in the human macula and whole retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:850–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman RE, Jr, Peloquin SJ. Crossability of 24-chromosome potato hybrids with 48-chromosome cultivars. Eur Potato J. 1967;10:62–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02364258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MR. Tracking down plant genes: paths, patterns and footprints. Plant Cell. 1989;1:169–172. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.2.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogkamp TJH, van den Ende RGT, Jacobsen E, Visser RGF. Development of amylose-free (amf) monoploid potatoes as new basic material for mutation breeding in vitro. Potato Res. 2000;43:179–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02357958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovenkamp-Hermelink JHM, Jacobsen E, Pijnacker LP, de Vries JN, Witholt B, Feenstra WJ. Cytological studies on adventitious shoots and minitubers of a monoploid potato clone. Euphytica. 1988;39:213–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00037098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanzik W, Tevini M, Stute R, Hilbert R. Caotenoidgehalt und–zusammensetzung verschiedener deutscher Kartoffelsorten und deren Bedeutung für die Fleischfarbe der Knolle. Potato Res. 1983;26:149–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02357477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JME, van Eck HJ, Arens P, Verkerk-Bakker B, te Lintel Hekkert B, Bastiaanssen HJM, El-Kharbotly A, Pereira A, Jacobsen E, Stiekema WJ. A genetic map of potato (Solanum tuberosum) integrating molecular markers, including transposons, and classical markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;91:289–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00220891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen E. Increase of diplandroid formation and seed set in 4x X 2x crosses in potatoes by genetical manipulation of dihaploids and some theoretical consequences. Z Pflanzenzuecht. 1980;85:110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen E, Hovenkamp-Hermelink JHM, Krijgsheld HT, Nijdam H, Pijnacker LP, Witholt B, Feenstra WJ. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of an amylose-free starch mutant of the potato. Euphytica. 1989;44:43–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00022597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GCL, Esposito L, Baratt BJ, Smith AN, Heward J, Di Genova G, Ueda H, Cordell HJ, Eaves IA, Dudbridge F, Twells RCJ, Payne F, Hughes W, Nutland S, Stevens H, Carr P, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Tuomilehto J, Gough SCL, Clayton DG, Todd JA. Haplotype tagging for the identification of common disease genes. Nat Genet. 2001;29:233–237. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Tempel S, Jurka J. Simple and fast classification of non-LTR retrotransposons based on phylogeny of their RT domain protein sequences. Gene. 2009;448:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman B, De Koeyer D, Griffiths R, Flinn B, Steuernagel B, Scholz U, Sonnewald S, Sonnewald U, Bryan GJ, Prat S, Bánfalvi Z, Hammond JP, Geigenberger P, Nielsen KL, Visser RGF, Bachem CWB. Genes driving potato tuber initiation and growth: identification based on transcriptional changes using the POCI array. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008;8:329–340. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman B, Oortwijn M, Celis-Gamboa C, Uitdewilligen J, America T, de Vos R, Visser RGF, Bachem C. From QTL to candidate gene: a genetical genomics approach using a pooling strategy for simple and complex traits in potato. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Ohara-Takada A, Tsuda S, Matsuura-Endo C, Takada N, Umemura Y, Nakao T, Yoshida T, Hayashi K, Mori M. Breeding of potato variety “Inca-no-hitomi” with a very high carotenoid content. Breed Sci. 2008;58:77–82. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.58.77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kort J, Jaspers CP, Dijkstra DL. Testing for resistance to pathotype C of Heterodera rostochiensis and the practical application of Solanum vernei-hybrids in the Netherlands. Ann Appl Biol. 1972;71:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1972.tb05098.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky NI, Mayne ST, Sies H. Carotenoids in health and disease. New York: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbourn GJ, Veilleux RE. Production and evaluation of somatic hybrids derived from monoploid potato. Amer J Potato Res. 2007;84:425–435. doi: 10.1007/BF02987188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AB, Van Eck J, Conlin BJ, Paolillo DJ, O’Neill J, Li L. Effect of the cauliflower Or transgene on carotenoid accumulation and chromoplast formation in transgenic potato tubers. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:213–223. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin E, Nussaume L, Quesada A, Gonneau M, Sotta B, Hugueney P, Frey A, Marion-Poll A. Molecular identification of zeaxanthin epoxidase of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia, a gene involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis and corresponding to the ABA locus of Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 1996;15:2331–2342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, He Y, Scortecci KC, Amasino RM. Attenuation of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity as a mechanism for the evolution of summer-annual flowering behavior in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10102–10107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531467100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SM, Parekh N, Tinker L, Ritenbaugh C, Blodi B, Wallace RB, Mares JA. Associations between intermediate age-related macular degeneration and lutein and zeaxanthin in the carotenoids in age-related eye disease study (CAREDS) Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1151–1162. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.8.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris WL, Ducreux L, Griffiths DW, Stewart D, Davies HV, Taylor MA. Carotenogenesis during tuber development and storage in potato. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:975–982. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterenko S, Sink KC. Carotenoid profiles of potato breeding lines and selected cultivars. HortScience. 2003;38:1173–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting the effects of amino acid substitutions on protein function. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:61–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot N, Hausman JF, Hoffmann L, Evers D. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:2907–2914. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obukhanych T, Jurka J. RTE1_ZM. Repbase Rep. 2007;7:988. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori Y, Abiko M, Horibata A, Hirano HY. A transposon, Ping, is integrated into intron 4 of the DROOPING LEAF gene of rice, weakly reducing its expression and causing a mild drooping leaf phenotype. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:176–1184. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TH, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Kim JB, Hutten RCB, Visser RGF. Dissection of foliage and tuber late blight resistance in mapping populations of potato. Euphytica. 2005;143:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-2658-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter E, Barandalla L, López R, Ruiz de Galarreta JI. Exploitation of exotic, cultivated Solanum germplasm for breeding and commercial purposes. Potato Res. 2008;51:301–311. doi: 10.1007/s11540-008-9109-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SO, Bendich AJ (1988) Extraction of DNA from plant tissues. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA (eds) Plant molecular biology manual. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp A6/1–A6/10

- Römer S, Lübeck J, Kauder F, Steiger S, Adomat C, Sandmann G. Genetic engineering of a zeaxanthin-rich potato by antisense inactivation and co-suppression of carotenoid epoxidation. Metab Eng. 2002;4:263–272. doi: 10.1006/mben.2002.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouppe van der Voort JNAM, van Zandvoort P, van Eck HJ, Folkertsma RT, Hutten RCB, Draaistra J, Gommers FJ, Jacobsen E, Helder J, Bakker J (1997) Use of allele specificity of comigrating AFLP markers to align genetic maps from different potato genotypes. Mol Gen Genet 255:438–447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD, Hiller R, Blair N, Burton TC, Farber MD, Gragoudas ES, Haller J, Miller DT, et al. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. JAMA. 1994;272:1413–1420. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.18.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodderly DM. Evidence for protection against age-related macular degeneration by carotenoids and antioxidant vitamins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62(suppl):1448S–1461S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1448S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerburg O, Keunen JEE, Bird AC, van Kuijk FJGM. Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:907–910. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.8.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Sasaki N, Ohmiya A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008;54:733–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorup TA, Tanyolac B, Livingstone KD, Popovsky S, Paran I, Jahn M. Candidate gene analysis of organ pigmentation loci in the Solanaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11192–11197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uijtewaal BA. Ploidy variability in greenhouse cultured and in vitro propagated potato (Solanum tuberosum) monohaploids (2n = x = 12) as determined by flow cytometry. Plant Cell Rep. 1987;6:252–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00268493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uijtewaal BA, Huigen DJ, Hermsen JGTh. Production of potato monohaploids (2n = x = 12) through prickle pollination. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;73:751–758. doi: 10.1007/BF00260786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Beek JG, Verkerk R, Zabel P, Lindhout P. Mapping stategy for resistance genes in tomato based on RFLPs between cultivars: CF9 (resistance to Cladosporium fulvum) on chromosome 1. Theor Appl Genet. 1992;84:106–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00223988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen JW. MapQTL® 5. Software for the mapping of quantitative trait loci in experimental populations. Wageningen: Kyazma BV; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen JW. JoinMap® 4. Software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps in experimental populations. Wageningen: Kyazma BV; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Os H, Andrzejewski S, Bakker E, Barrena I, Bryan GJ, Caromel B, Ghareeb B, Isidore E, de Jong W, van Koert P, Lefebvre V, Milbourne D, Ritter E, Rouppe van der Voort JNAM, Rousselle-Bourgeois F, van Vliet J, Waugh R, Visser RGF, Bakker J, van Eck HJ (2006) Construction of a 10,000-marker ultradense genetic recombination map of potato: providing a framework for accelerated gene isolation and a genomewide physical map. Genetics 173:1075–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.