Abstract

Context:

SIDS remains the leading cause of postneonatal death in the US. To decrease risk, infants should be placed supine for sleep.

Objective:

Determine trends and factors associated with choice of infant sleeping position.

Design:

National Infant Sleep Position Study (NISP): Annual nationally representative telephone surveys.

Setting:

48 contiguous states of the United States.

Participants:

Nighttime caregivers of infants born within the last 7 months between 1993 and 2007. Approximately 1000 interviews each year.

Main Outcome Measure:

Infant usually placed to sleep in the supine position.

Results:

For the 15-year period, supine sleep increased (p<0.0001) and prone sleep decreased (p<0.0001) for all infants with no significant difference in trend by race. Since 2001 a plateau has been reached for all races.

Factors associated with increase supine sleep between 1993-2007 included: time, maternal race other than Black, higher maternal education, not living in Southern States, first-born infant, and full-term infant. Impact of these variables was reduced when variables related to maternal concerns about infant comfort, infant choking and advice received from doctors were taken into account.

Between 2003 and 2007, choice of infant sleep position could be explained almost entirely by caregiver concern about comfort, choking and advice. Race no longer was a significant predictor of supine sleep.

Conclusions:

Since 2001 supine sleep has reached a plateau, and there continue to be racial disparities in both sleep practice and death rates. There have been changes in factors associated with sleep position and maternal attitudes about issues such as comfort and choking concerns may account for much of the racial disparity in practice. To decrease SIDS, we must ensure that public health measures reach the populations at risk and include messages that address concerns about infant comfort or choking in the supine position.

INTRODUCTION

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome remains the leading cause of postneonatal death in the United States, accounting for approximately 2200 infant deaths each year.1 Although the etiology of SIDS is unknown, placing the infant to sleep in the supine position has been found to be significantly associated with a decrease in the SIDS rate.2

There has been a dramatic decrease in the incidence of SIDS in the United States since the Back to Sleep Campaign began in 1994. Despite this overall decrease in the incidence of SIDS, Black infants continue to have a higher incidence of SIDS, more than double that seen in White infants.1 Previous research has also shown that Black infants are less likely to be placed in the supine position for sleep when compared to White infants.3,4,5 The National Infant Sleep Position Study (NISP), an annual national telephone survey, has been designed to track national trends in infant care practices related to SIDS, including sleep position, to examine the efficacy of the Back to Sleep Campaign and other efforts to change sleep position practice. Much of what is currently known about trends in infant care practices in the United States and factors associated with these practices has been derived from the NISP surveys.4,6 The objectives of this current report is to examine trends in infant sleeping position, to understand factors associated with choice of infant sleeping position, and to identify barriers to further change in practice using data from the inception of the surveys in 1993 through 2007.

METHODS

Sample

The data used in the analysis for this study is part of the National Infant Sleep Position Study (NISP). Data Stat Inc (Ann Arbor Michigan) conducted annual telephone surveys by randomly sampling households with infants 7 months of age and younger from a nationally representative list. The list is purchased from Metromail (Lincoln, Nebraska) and is generated using public information from sources including birth records, infant photography companies and formula companies. The list is compiled to give appropriate geographic representation of the 48 contiguous states. Interviews were completed if the respondent answered “yes” to the question: “Is there an infant in the house born in the last 7 months, that is on or after (date)”. More than 80% of the respondents each year were the infants' mothers. The goal was to complete approximately 1000 calls each year. The number of calls completed ranged from 1012 to 1188 between 1993 and 2007. The response rate calculations describe in previous research ranged from 58% to 83% during the same years.6

Measures

The survey was designed for the NISP study.6 All surveys are available for viewing on the National Infant Sleep Position Study Public Access Website.7 The results presented here focus on infant sleeping position, with dependent variables based on the response to the question: “Do you have a position you USUALLY place your baby in?” Factors examined as independent variables that might influence sleep position were chosen based on previous work identifying factors associated with sleep position including year, maternal demographic variables (maternal age, race, and education, household income, region of country), child variables (child age, sex, prematurity status, and sleep location), maternal concerns about infant comfort and infant choking, and doctor's advice about sleep position (categorized as supporting supine, not supporting supine, or no advice). 2,3,4,5,6

Participants were asked about their race/ethnicity because of the health disparities seen in SIDS and in infant care practices. All participants were asked during the telephone interview: “Which of the following best describes [the mother's] racial or ethnic background? The interviewer then read: White, African American, Hispanic, Asian, Native American and Some Other Race. If they chose “Some other Race”, the participant was asked to specify. It was also documented if the participant refused to answer or said that they did not know.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated including frequencies and percentages. The main outcome variable was: usually sleeps in the supine position. Chi Square tests were used to test for differences in proportions across demographic subgroups. Trends over time in supine, prone, and lateral sleep position were examined through logistic regression fitting linear change in log-odd over time, controlling for race. Racial differences in trends over time were examined through interaction models. Plots of sleep position over time suggest a change in trend lines at 2001, and so separate models examined trends from 1993 – 2000 and from 2001 to 2007. Multiple logistic regression was also used to examine associations between supine sleep position and maternal and infant factors potentially related to sleep position, controlling for categorized year from 1993 to 2007. To better understand changes in associations between factors and sleep position over time, the data were also analyzed separately for the three five-year time periods: 1993-1997, 1998-2002, and 2003-2007.

This research study was approved by the Internal Review Boards at Boston University School of Medicine and at Yale University School of Medicine.

RESULTS

Trends in the Position Placed, 1993-2007

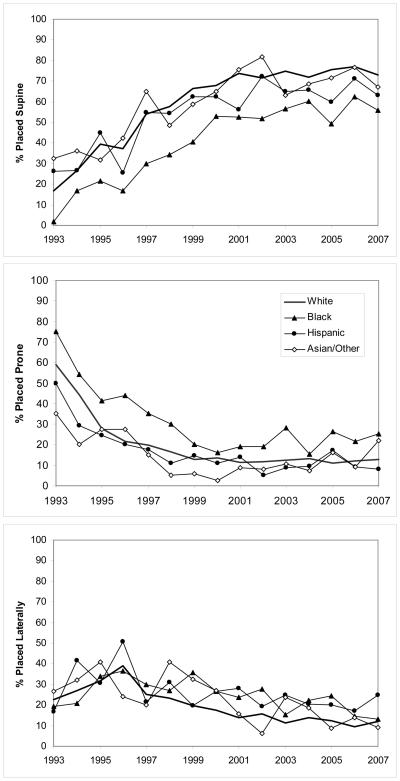

When asked “Do you have a position you usually place the baby to sleep”, ninety-nine percent replied affirmatively. Figure 1 shows the changes in usual sleeping position by race/ethnicity for the period 1993 through 2007. Between 1993 and 2000, there was a clear increase in supine sleeping and a decrease in prone sleeping in each of the racial/ethnic groups. Logistic regression models showed significant increases in supine sleep (p<0.0001) and significant decreases in prone sleep (p<0.0001), with no significant differences in the trends by race (tests for race by time interaction gave p=0.092 for supine, p=0.707 for prone position). However, the Black population has consistently had the lowest use of the supine position for sleep and the highest use of the prone position (p < 0.005 for comparison with Whites based on logistic regression analyses). Hispanics did not significantly differ from Whites on prone sleep (p=0.730). Use of the lateral sleep position has been relatively stable over the entire 15-year period with only minor differences between racial/ethnic groups. Since 2001, there has been little change in sleep position practices, with no significant change in sleep position over time (p=0.162 for supine sleep, p=0.369 for prone sleep) and no significant differences in trends over time by race (p=0.443 for interaction between race and time for supine sleep, p=0.210 for prone sleep). Supine sleep has reached a plateau of approximately 75% and 58%, and prone sleeping position has reached a plateau of approximately 10% and 20%, in the White and Black populations respectively.

Figure 1.

Percentage of study infants usually placed in the supine (top), prone (middle), or lateral (bottom) positions from 1993-2007

Factors Associated with Usual Supine Sleep Position 1993-2007

To assess the factors associated with usual supine sleep position we initially performed a multiple logistic regression analysis in which the explanatory variables included survey year, geographic region, as well as fixed characteristics of mothers and infants (maternal age, education, race, income and parity categories, and infant age and prematurity status categories). The results of this analysis are provided in Table 1, with the adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) for each variable shown in column 5. Survey year is the strongest predictor of supine sleep position, with odds ratios, compared to the reference year of 1993, steadily increasing from 1.8 in 1994 to 13 in 2001, however, there was little change between 2001 and 2007. Other characteristics associated with greater likelihood of reporting usual supine sleep position included: maternal age being older, race other than Black, higher maternal educational level, higher maternal income level, mother not having other children, geographic region other than the Southern US, infant age being older, and infant being born at >37 weeks gestation.

Table 1.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Usual Supine Sleep Position for 1993 – 2007 (N=13580)

| Variable | Total N (%) |

Usually supine N (%) |

Usually supine Adj. OR (95% CI) |

Usually Supine Adj. OR (95% CI) Behavioral Variables Added |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1993 | 905 (6.7) | 153 (16.9) | reference | reference |

| 1994 | 871 (6.4) | 232 (26.6) | 1.77 (1.40; 2.23)* | 1.72 (1.35; 2.20)* | |

| 1995 | 911 (6.7) | 348 (38.2) | 2.99 (2.40; 3.73)* | 2.45 (1.94; 3.10)* | |

| 1996 | 860 (6.3) | 298 (34.7) | 2.74 (2.19; 3.44)* | 2.14 (1.68; 2.72)* | |

| 1997 | 898 (6.6) | 484 (53.9) | 5.77 (4.63; 7.20)* | 4.25 (3.36; 5.38)* | |

| 1998 | 873 (6.4) | 494 (56.6) | 6.38 (5.10; 7.96)* | 4.14 (3.26; 5.26)* | |

| 1999 | 917 (6.8) | 601 (65.5) | 9.72 (7.76; 12.16)* | 5.49 (4.32; 6.99)* | |

| 2000 | 867 (6.4) | 584 (67.4) | 10.47 (8.34; 13.16)* | 5.81 (4.54; 7.42)* | |

| 2001 | 879 (6.5) | 635 (72.2) | 12.55 (9.95;15.82)* | 6.12 (4.76; 7.86)* | |

| 2002 | 1015 (7.5) | 723 (71.2) | 12.2 (9.75; 15.27)* | 5.76 (4.51; 7.34)* | |

| 2003 | 919 (6.8) | 673 (73.2) | 13.03 (10.35; 16.42)* | 6.77 (5.28; 8.70)* | |

| 2004 | 925 (6.8) | 655 (70.8) | 12.16 (9.68; 15.27)* | 5.38 (4.20; 6.89)* | |

| 2005 | 891 (6.6) | 649 (72.8) | 13.88 (11.00; 17.52)* | 6.47 (5.02; 8.34)* | |

| 2006 | 942 (6.9) | 723 (76.8) | 16.92 (13.38; 21.39)* | 7.26 (5.62; 9.37)* | |

| 2007 | 907 (6.7) | 650 (71.7) | 12.74 (10.11; 16.04)* | 5.13 (3.99; 6.60)* | |

|

| |||||

| Mother's Age | Less than 20 | 601 (4.4) | 303 (50.4) | reference | reference |

| 20 to 29 | 6725(49.) | 3808 (56.6 | 1.14 (0.94; 1.38) | 1.01 (0.83; 1.24) | |

| 30 or more | 6254 (46.1) | 3791 (60.6) | 1.24 (1.02; 1.52)* | 1.03 (0.83; 1.28) | |

|

| |||||

| Mother's Race | Black | 738 (5.4) | 307 (41.6) | reference | reference |

| White | 11480 (84.5) | 6767 (58.9) | 1.94 (1.65; 2.29)* | 1.83 (1.52; 2.19)* | |

| Hispanic | 814 (6.0) | 474 (58.2) | 1.73 (1.39; 2.16)* | 1.91 (1.50; 2.42)* | |

| Asian/Other | 548 (4.0) | 354 (64.6) | 2.05 (1.60; 2.63)* | 2.09 (1.60; 2.74)* | |

|

| |||||

| Mother's Education | Up to college | 7461 (54.9) | 3965 (53.1) | reference | reference |

| College/more | 6119 (45.1) | 3937 (64.3) | 1.27 (1.16; 1.38)* | 1.11 (1.01; 1.23)* | |

|

| |||||

| Household Income | Less than $20,000 | 1958 (14.4) | 939 (48) | reference | reference |

| 20,000 to $50,000 | 5348 (39.4) | 2856 (53.4) | 1.08 (0.96; 1.21) | 1.04 (0.91; 1.18) | |

| $50,000 or more | 6274 (46.2) | 4107 (65.5) | 1.22 (1.07; 1.39)* | 1.05 (0.91; 1.22) | |

|

| |||||

| US Region | South | 4661 (34.3) | 2502 (53.7) | reference | reference |

| Midwest | 4231 (31.2) | 2608 (61.6) | 1.47 (1.34; 1.62)* | 1.39 (1.26; 1.54)* | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 1870 (13.8) | 1079 (57.7) | 1.25 (1.11; 1.41)* | 1.21 (1.07; 1.38)* | |

| New England | 727 (5.4) | 446 (61.3) | 1.43 (1.20; 1.71)* | 1.33 (1.09; 1.61)* | |

| West | 2091 (15.4) | 1267 (60.6) | 1.51 (1.34; 1.69)* | 1.46 (1.28; 1.65)* | |

|

| |||||

| Parity | More than one | 6846 (50.4) | 3841 (56.1) | reference | reference |

| One | 6734 (49.6) | 4061 (60.3) | 1.31 (1.21; 1.42)* | 1.22 (1.12; 1.33)* | |

|

| |||||

| Infant's Gender | Male | 6981 (51.4) | 4027 (57.7) | reference | reference |

| Female | 6599 (48.6) | 3875 (58.7) | 1.08 (1.00; 1.16) | 1.08 (0.99; 1.17) | |

|

| |||||

| Infant's Age | Less than 8 weeks | 988 (7.3) | 511 (51.7) | reference | reference |

| 8 to 15 weeks | 4002 (29.5) | 2249 (56.2) | 1.23 (1.05; 1.43)* | 1.46 (1.23; 1.73)* | |

| 16 weeks or more | 8590 (63.3) | 5142 (59.9) | 1.47 (1.27; 1.71)* | 1.83 (1.55; 2.17)* | |

|

| |||||

| Prematurity (<37 wks) | Yes | 1487 (10.9) | 861 (57.9) | reference | reference |

| No | 12093 (89.1) | 7041 (58.2) | 1.17 (1.04; 1.32)* | 1.22 (1.07; 1.39)* | |

|

| |||||

| Sleep location | Crib | 9071 (66.8) | 5232 (57.7) | - | reference |

| Adult bed | 1286 (9.5) | 759 (59) | - | 1.06 (0.92; 1.22) | |

| Bassinet | 1793 (13.2) | 1091 (60.8) | - | 1.06 (0.93; 1.21) | |

| Other | 1430 (10.5) | 820 (57.3) | - | 0.99 (0.87; 1.14) | |

|

| |||||

| Position choice related to comfort |

Yes | 5144 (37.9) | 1972 (38.3) | - | reference |

| No | 8436 (62.1) | 5930 (70.3) | - | 3.94 (3.62; 4.29)* | |

|

| |||||

| Position choice related to choking |

Yes | 1359 (10.0) | 325 (23.9) | - | reference |

| No | 12221 (90.0) | 7577 (62) | - | 5.18 (4.46; 6.00)* | |

|

| |||||

| Advice from doctor | No advice | 4711 (34.7) | 2073 (44) | - | reference |

| Not in favor of supine | 4474 (32.9) | 2146 (48) | - | 0.92 (0.84; 1.01) | |

| In favor of supine | 4395 (32.4) | 3683 (83.8) | - | 3.05 (2.72; 3.41)* | |

95% CI does not include 1.00

To assess the extent to which certain maternal attitudes or practices may also impact usual supine sleep position we performed a second multiple logistic regression analysis in which the following potential explanatory variable were added to those described above: usual sleep location (bassinet, crib, adult bed, other), reported maternal concern about infant choking, reported maternal concern about infant comfort and reported doctor advice received (supine, non-supine, none). The adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) for this second analysis can be found in column 6 of Table 1. Three of these four added variables (i.e. all but usual sleep location) were strongly associated with usual supine sleep position. Although only 10% of mothers reported concerns about choking, mothers who did not report this concern had 5 times the odds of reporting usual supine sleep position. Almost 38% of mothers reported a concern about infant comfort, with those not reporting this concern having 4 times the odds of choosing usual supine sleep position. Only one third of mothers reported receiving positive advice from their doctor to use the supine sleep position, with one third reporting negative advice regarding supine position and one third reporting receiving no advice. Mothers receiving positive advice had three times the odds of reporting usual supine position compared to either negative advice or to receiving no advice.

When taking the four additional variables into account, the magnitude of the odds ratios of many of the other variables were reduced, such that maternal age and income no longer reached statistical significance, and the magnitude of the odds ratios for survey years 1999 – 2007 were reduced by approximately 50%.

Changes over Time in Factors Associated with Usual Supine Sleep Position

To assess the extent to which the factors associated with usual supine sleep position have changed over time, we repeated the above multiple logistic regression analyses with analyses restricted to each of three successive five-year time windows: 1993-1997, 1998-2002, and 2003-2007. Table 2 shows the results of these analyses. Important findings from these analyses include the following:

In the earliest time window, survey year is a strong predictor of supine sleep position, however the association is less strong in the middle time window and within the most recent time window there is no longer an increase over time, and there is even be a suggestion of decreasing use of supine position with time. Comparing 2003 and 2007 in the most recent time period there are statistically fewer infants placed in the supine position in 2007.

In the most recent time period (2003-2007), most of the demographic variables that were associated with supine sleep position in earlier time periods are no longer significantly associated with supine sleep position. The only variables that remains consistently significant in the time period 2003-2007 is living in a Midwestern state and Hispanic ethnicity. In the most recent time period, 2003-2007, the differences in use of supine sleep position can be explained almost entirely by the variables maternal concern about comfort, maternal concern about choking and advice from a doctor to place the infant in the supine position for sleep.

The prevalence of maternal concerns about infant comfort and infant choking with regard to sleep position have decreased over time. Concerns about infant choking decreased from 16.8% to 7.1% to 6.3% of mothers from the earliest to the most recent time period (p<0.0001 from chi-square test). Similarly, concerns about infant comfort decreased from 49.4% to 34.1% to 30.5% during these same time periods (p<0.0001). However, the importance of these factors in predicting supine sleep position increased over time, such that in the most recent time period, mothers who were not concerned about choking had 8 times the odds of reporting usual use of supine position, and mothers not concerned about comfort had 12 times the odds or reporting usual use of supine.

The prevalence of mothers reporting positive advice from a doctor regarding supine position increased over time from 5.8% in the earliest time period to 36.9% to 53.6% in the most recent time period (p<0.0001). Receiving positive advice remains important in the most recent time period, with mothers receiving positive advice having 2.6 times the odds of reporting usual supine position, compared to no advice, and those receiving negative advice having 30% lower odds of reporting usual supine position compared to those receiving no advice.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Usual Supine Sleep Position within Consecutive 5-Year Time Windows

| Variable | Usually supine Adj. OR (95% CI) 1993-1997 N=4445 |

Usually supine Adj. OR (95% CI) 1998-2002 N=4551 |

Usually supine Adj. OR (95% CI) 2003-2007 N=4584 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year** | 1 | reference | reference | reference |

| 2 | 1.60 (1.25; 2.04)* | 1.33 (1.08; 1.65)* | 0.73 (0.57; 0.93)* | |

| 3 | 2.40 (1.90; 3.03)* | 1.42 (1.14; 1.76)* | 0.82 (0.64; 1.06) | |

| 4 | 2.37 (1.87; 3.01)* | 1.50 (1.20; 1.87)* | 0.97 (0.75; 1.25) | |

| 5 | 3.97 (3.14; 5.02)* | 1.40 (1.13; 1.74)* | 0.67 (0.52; 0.86)* | |

|

| ||||

| Mother's Age | Less than 20 | reference | reference | reference |

| 20 to 29 | 1.09 (0.78; 1.53) | 0.95 (0.67; 1.34) | 1.03 (0.68; 1.57) | |

| 30 or more | 1.32 (0.92; 1.90) | 0.85 (0.59; 1.23) | 0.96 (0.61; 1.50) | |

|

| ||||

| Mother's Race | Black | reference | reference | reference |

| White | 2.02 (1.41; 2.90)* | 2.16 (1.61; 2.90)* | 1.38 (0.99; 1.92) | |

| Hispanic | 2.34 (1.47; 3.74)* | 2.03 (1.37; 30.0)* | 1.58 (1.03; 2.44)* | |

| Asian/Other | 3.23 (1.93; 5.42)* | 2.27 (1.45; 3.55)* | 1.41 (0.88; 2.28) | |

|

| ||||

| Mother's Education | Up to college | reference | reference | reference |

| College/more | 1.17 (1.00; 1.37) | 1.17 (1; 1.38) | 0.96 (0.80; 1.16) | |

|

| ||||

| Household Income | Less than $20,000 | reference | reference | reference |

| 20,000 to $50,000 | 1.00 (0.82; 1.23) | 1.03 (0.82; 1.29) | 1.22 (0.93; 1.58) | |

| $50,000 or more | 1.01 (0.80; 1.28) | 1.14 (0.89; 1.46) | 1.11 (0.84; 1.47) | |

|

| ||||

| US Region | South | reference | reference | reference |

| Midwest | 1.54 (1.29; 1.84)* | 1.22 (1.02; 1.45)* | 1.43 (1.17; 1.73)* | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 1.12 (0.89; 1.40) | 1.33 (1.08; 1.65)* | 1.15 (0.88; 1.50) | |

| New England | 1.49 (1.10; 2.03)* | 1.11 (0.80; 1.54) | 1.34 (0.89; 2.03) | |

| West | 1.66 (1.35; 2.05)* | 1.50 (1.20; 1.87)* | 1.15 (0.90; 1.47) | |

|

| ||||

| Parity | More than one | reference | reference | reference |

| One | 1.37 (1.18; 1.59)* | 1.19 (1.03; 1.38)* | 1.14 (0.96; 1.36) | |

|

| ||||

| Infant's Gender | Male | reference | reference | reference |

| Female | 1.04 (0.90; 1.19) | 1.15 (1.00; 1.32) | 1.06 (0.90; 1.24) | |

|

| ||||

| Infant's Age | Less than 8 weeks | reference | reference | reference |

| 8 to 15 weeks | 2.90 (2.02; 4.16)* | 1.37 (1.00; 1.89) | 1.02 (0.74; 1.41) | |

| 16 weeks or more | 4.26 (2.99; 6.07)* | 1.86 (1.36; 2.55)* | 0.91 (0.67; 1.24) | |

|

| ||||

| Prematurity (<37 weeks) | Yes | reference | reference | reference |

| No | 1.38 (1.08; 1.76)* | 1.3 (1.03; 1.62)* | 1.15 (0.90; 1.46) | |

|

| ||||

| Sleep location | Crib | reference | reference | reference |

| Adult bed | 1.57 (1.19; 2.07)* | 1.10 (0.88; 1.38) | 0.74 (0.57; 0.96)* | |

| Bassinet | 1.00 (0.78; 1.28) | 1.09 (0.87; 1.36) | 1.02 (0.80; 1.29) | |

| Other | 1.06 (0.84; 1.34) | 1.04 (0.82; 1.33) | 0.92 (0.71; 1.18) | |

|

| ||||

| Position choice related to comfort |

Yes | reference | reference | reference |

| No | 1.55 (1.35; 1.79)* | 4.27 (3.68; 4.94)* | 11.45 (9.66; 13.57)* | |

|

| ||||

| Position choice related to choking |

Yes | reference | reference | reference |

| No | 4.13 (3.22; 5.31)* | 4.93 (3.81; 6.38)* | 7.70 (5.76; 10.29)* | |

|

| ||||

| Advice from doctor | No advice | reference | reference | reference |

| Not in favor of supine | 1.11 (0.96; 1.28) | 0.93 (0.79; 1.09) | 0.70 (0.56; 0.86)* | |

| In favor of supine | 5.78 (4.15; 8.05)* | 2.89 (2.40; 3.47)* | 2.62 (2.17; 3.17)* | |

95% CI does not include 1.00

Year categories (1-5) for each time interval correspond to range from earliest to latest year of the time interval

DISCUSSION

While the Back to Sleep Campaign was highly successful in the initial years in increasing supine sleeping thereby decreasing the rate of SIDS2,4,6, our data show that more recently prevalence of supine sleep position has reached a plateau. The questions for public health officials then become: Who continues to place infants in the non-supine position, why do they continue and have the factors associated with non-supine sleep changed since the Back to Sleep campaign was initiated in 1994? Our research has provided some insight into the answers to these questions.

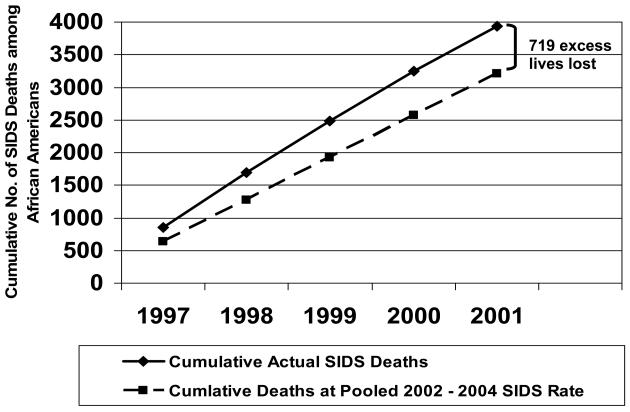

Through this current study we have learned a number of things about choice of infant sleeping position. First, in examining the graphs of the time trends, it is clear that there is a plateau for all racial/ethnic groups. It is particularly concerning that the trend could be heading in the opposite direction. Second, racial disparity continues to exist with regard to infant sleeping position. To the extent that sleep position contributes to sudden unexpected death rates, this disparity has likely led to a high number of potentially preventable deaths among Black infants. The potential impact of the slower adoption of supine sleep position among Black as compared to White families is shown in Figure 2. This figure shows the actual cumulative number of infant deaths among Black infants in the US from 1997 – 2001 and compares it to the cumulative number of deaths that would have occurred if the SIDS rate achieved for the pooled years 2002 - 2004 had been achieved as early as 1997. The pooled SIDS rate for years 2002 - 2004 (1911 deaths among 1,809,679 births for a rate of 1.056/1,000) was chosen because both the supine sleeping rate as well as the SIDS rate was stable during this period. The calculation was started beginning in 1997 because this was the year that White infants achieved a rate of supine sleeping comparable to that of Black infants in 2002 (i.e. 58% supine sleeping). From the figure one can see that had the improvement in rate of supine sleeping been achieved in Black infants by 1997, as it had in White infants, and had been accompanied by the SIDS rate that was actually observed among Black infants in 2002 - 2004, than 719 fewer Black infants would have died during this 5-year period (a decrease of 18%).

Figure 2.

Cumulative Number of SIDS Deaths Among Black Infants Actual Number of SIDS Deaths vs. SIDS Deaths Calculated Using Pooled 2002 - 2004 SIDS Rate

Third, what we have also learned related to racial disparity is that most recently, between 2003 and 2007, the difference in supine sleep between Black and White infants can be explained, at least in part, by caregiver concern about choking and comfort and whether the caregiver received doctor advice to place the infant in the supine position for sleep. While the prevalence of choice of sleep position being related to issues of comfort and choking decreased markedly over time, the relative importance of these attitudes as predictors of sleep position has increased.

Receiving advice from a doctor for supine sleep position has remained a strong predictor of supine sleeping over time and has markedly increased in prevalence. However, more than 45% of mothers reported either receiving no advice from their doctor or receiving advice to sleep in a non-supine position.

Potential limitations of this study include its reliance on telephone contact which results in under representation of minority and low-income care providers. In addition, all data are based on caretaker report, which may not accurately reflect actual behavior.

CONCLUSION

Although changing sleep position has proven to be a successful means to decrease risk is for sudden unexpected infant death, since 2001 we have reached a plateau in the number of infants who sleep in the supine position, and there continue to be large racial disparities in both sleep practice and death rates. Over time, there have been changes in the important factors associated with sleep position and it appears that maternal attitudes about issues such as comfort and choking concerns may account for much of the racial disparity in practice. If we are to further reduce death rates, we need to ensure that public health measures reach the populations at highest risk and include messages that address concerns about infant comfort or choking in the supine position. We must remain vigilant about tracking trends in infant care practices particularly as we are seeing evidence of slippage in adherence to the recommendations. Finally, we need to better define other maternal attitudes that may lead to using non-supine sleep position, and identify if there are other factors that may prevent adoption of this advice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This work was supported in part by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant U10 HD029067-09A1C. Dr. Colson and Corwin had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

We thank Timothy Hereen, PhD, Marian Willinger, PhD and Isabelle VonKohorn, MD for their thoughtful reviews of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The following specific contributions were made by the authors:

Study concept and design: Colson, Smith, Colton, Lister, Corwin

Acquisition of data: Corwin, Rybin

Analysis and interpretation of data: Colson, Rybin, Smith, Colton, Lister, Corwin

Drafting of the manuscript: Colson, Corwin

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Colson, Corwin, Rybin, Smith, Colton, Lister

Statistical analysis: Rybin, Colton

Obtained funding: Corwin

Administrative, technical, or material support: Corwin, Colson, Lister

Study supervision: Corwin

Contributor Information

Eve R. Colson, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, Eve.Colson@Yale.edu.

Denis Rybin, Data Coordinating Center, Boston University School of Public Health, DRybine@bu.edu.

Lauren A. Smith, Massachusetts Department of Health, Lauren.Smith@state.ma.us.

Theodore Colton, Department of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, TColton@bu.edu.

George Lister, Department of Pediatrics, UT Southwestern Medical Center, George.Lister@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Michael J. Corwin, Departments of Pediatrics and Epidemiology, Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health, MJCorwin@bu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality from 2004 period linked birth/death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;55:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kattwinkel J, Hauck FR, Keenan ME, Malloy MH, Moon RY. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, American Academy of Pediatrics. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1245–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colson ER, Levenson S, Rybin D, et al. Barriers to following the supine sleep recommendation among mothers at four centers for the Women, Infants, and Children Program. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e243–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willinger M, Ko CW, Hoffman HJ, Kessler RC, Corwin MJ. Factors associated with caregivers' choice of infant sleep position, 1994–1998: the National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA. 2000;283:2135–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner RA, Simons-Morton BG, Bhaskar B, et al. Prevalence and predictors of the prone sleep position among inner-city infants. JAMA. 1998;280:341–346. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willinger M, Hoffman HJ, Wu K-T, et al. Factors associated with the transition to nonprone sleep positions of infants in the United States: The National Infant Sleep Position Study. JAMA. 1998;280:329–335. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Infant Sleep Position Public Access Web Site Available at: http://dccwww.bumc.bu.edu/ChimeNisp/Main.Nisp.asp. Accessed March 3, 2009.