Abstract

Chondrocytes in articular cartilage normally exhibit high expression of collagen II and aggrecan but rapidly dedifferentiate to a fibroblastic phenotype if passaged in culture. Previous studies have suggested that the loss of chondrocyte phenotype is associated with changes in the structure of the F-actin cytoskeleton, which also controls cell mechanical properties. In this study, we examined how dedifferentiation in monolayer influences the mechanical properties of chondrocytes isolated from different zones of articular cartilage. Atomic force microscopy was used to measure the mechanical properties of superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes as they underwent serial passaging and subsequent growth on fibronectin-coated, micropatterned self-assembled monolayers that restored a rounded cell shape in 2D culture. Chondrocytes exhibited significant increases in elastic and viscoelastic moduli with dedifferentiation in culture. These changes were only partially ameliorated by the restoration of a rounded shape on micropatterned surfaces. Furthermore, intrinsic zonal differences in cell mechanical properties were rapidly lost with passage. These findings indicate that cell mechanical properties may provide additional measures of phenotypic expression of chondrocytes as they undergo dedifferentiation and possibly redifferentiation in culture.

Keywords: Atomic force microscope, Cell mechanics, Micropattern, Cartilage, Monolayer expansion, Morphology, Chondrocyte, Indentation, Differentiation

Introduction

Chondrocytes are the sole cell type in articular cartilage and exist as different subpopulations, depending on their zone of origin with respect to depth from the tissue surface.5 Innate differences in matrix structure and cell phenotype exist among the zones (superficial, middle, deep), which are believed to arise from structure–function relationships associated with location in the joint and tissue.1–3,10,23,33,41 Previous studies have shown that chondrocytes expanded in monolayer, as is often required for cell-based therapies,6,8,16 undergo “de-differentiation” and exhibit a more fibroblastic phenotype characterized by increased expression of collagen I relative to collagen II.6,8,16 However, some recovery of the chondrocytic phenotype can be achieved by restoring the rounded, three-dimensional morphology of the cell, either by encapsulation in a hydrogel or by disruption of the F-actin cytoskeleton.6,42 Other methodologies have been attempted to retain or restore normal gene and protein expression, but a spherical cell shape appears to be integral to the chondrocytic phenotype.9,30

The differentiation state of these cells generally has been assessed using phenotypic biomarkers such as gene and protein expression, cytoskeletal structure, and cell morphology. Recent studies suggest that another means of monitoring differentiation state may be through mechanical biomarkers such as the elastic or viscoelastic properties of the cell. The biomechanical properties of a cell can be recorded and analyzed through a variety of techniques.4,14,17,20,28,32,35,40 One of these techniques, atomic force microscopy (AFM), has been used previously to distinguish different cell lineages from single-cell biomechanical properties.11 Significant differences in elastic and viscoelastic properties were observed among cell types derived from the mesenchymal lineage. Furthermore, subpopulations within the chondrocytic lineage were distinguishable by their biomechanical properties alone.13 It is possible that the dedifferentiation process will affect mechanical characteristics of primary cells in a manner similar to other biological markers, providing an additional means of assessing cell phenotype.

The goal of this study was to evaluate how chondrocyte dedifferentiation affects mechanical properties associated with superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes. Past results have shown a dramatic change in the characteristic phenotypic expression of chondrocytes serially passaged in monolayer.7,8,25 A similar approach was used to monitor changes in the elastic and viscoelastic properties of passaged, zonal chondrocytes. In addition to these tests, the effect of restoring a spherical morphology on the chondrocytic phenotype was evaluated by culturing passaged cells on spatially restrictive micropatterns for either one or seven days following expansion. While serial expansion was hypothesized to cause a loss of the mechanical phenotype, induction of a spherical morphology was expected to induce re-differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Chondrocyte Isolation and Zonal Separation

Chondrocytes were isolated from articular cartilage harvested from the femoral condyles of skeletally mature, female pigs (N = 5), approximately 2 years in age, using a zonal abrasion technique to separate the superficial and middle/deep zones.10 Cells were extracted from the harvested tissue using enzymatic digestion. Briefly, the tissue was incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 1% (w/v) pronase (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and 5% (w/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) for 45 min at 37 °C and 5% (v/v) CO2. The tissue was subsequently incubated in DMEM containing 0.4% (w/v) type II collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) and 5% FBS for 90 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The resulting digest was strained through a 70-μm filter and rinsed with wash media (DMEM, 1.5× HEPES, 1× nonessential amino acids, 0.33% gentamicin (Invitrogen), 1× kanamycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 1× penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (PSF, Invitrogen)) before being counted using a hemocytometer. Cells were subsequently re-suspended in feed media (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1× PSF, 1.5× HEPES, and 1× nonessential amino acids) and plated according to described procedures. All cell expansion experiments were carried out on tissue culture-treated polystyrene.

Micropatterned Self-Assembled Monolayers (MSAMs)

To maintain chondrocytes in a rounded morphology in 2D culture, cells were grown on substrates containing micropatterned circular geometries of fibronectin that allowed attachment but not spreading of the cells. Silicon wafers with a repeating pattern of circles were fabricated in conjunction with the Center for Computer Integrated Systems for Microscopy and Manipulation at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and were used to make poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) stamps.15 Briefly, circles 8 μm in diameter and 50 μm apart, center to center, were patterned onto a chromium mask. The mask was aligned over a silicon wafer previously spin-coated with a photoresist and exposed to UV light, which cross-linked the exposed photoresist. The unexposed regions were then removed with a developer solution, resulting in holes of the desired dimensions (8 × 12 μm, diameter × depth). From these master silicon templates, a PDMS stamp was fabricated by first forming a release layer on the surface using (tridecafluoror-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)trichlorosilane (Gelest, Morrisville, PA), then pouring a 10:1 weight ratio mixture of PDMS polymer and curing agent (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) onto the template, followed by degassing and curing for 1 h at 90 °C.

MSAM substrates, consisting of protein adhesive and resistant regions, were created using these PDMS stamps following previously reported protocols.15 Briefly, glass coverslips were coated with 10 nm of titanium followed by 20 nm of gold using an electron beam evaporator. To pattern the resulting gold surfaces, PDMS stamps were sonicated in 50% ethanol for 15 min and inked with a 1 mM ethanolic solution of 1-octadecanthiol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and immediately blown dry with nitrogen gas. The stamps were backed with a glass slide and placed in conformal contact with the cleaned gold surfaces for 15 s creating patterned circles 8 μm in diameter that were protein adhesive. To create protein resistant regions, the coverslips were placed face-down on a 2 mM ethanolic solution of (1-mercapto-11-undecyl)tri(ethyleneglycol) (Asemblon, Redmond, WA). Coverslips were then incubated with fibronectin (100 μg/mL in PBS, Invitrogen) and blocked with 1% denatured bovine serum albumin (Invitrogen). Superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes were seeded immediately onto patterned coverslips and gently washed after 3 h to remove unattached cells.

Cell Passaging for Testing Without Micropatterns

Primary chondrocytes from the superficial and middle/deep zones of articular cartilage were plated separately in 35-mm Petri dishes at an initial seeding density of 100,000 cells/dish. Cells were allowed to proliferate until approximately 90% confluence, as determined visually, after which they were passaged by standard trypsinization techniques. Briefly, cells were released from surfaces by a 4–6 min treatment with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Sigma). Subsequently, passaged cells were digested with 0.4% type II collagenase for 15 min to remove any synthesized matrix, counted, and distributed accordingly. Twenty percent of the resulting cells were re-plated for continued expansion, 20% were seeded onto poly-l-lysine-coated polystyrene surfaces (PLL) for mechanical testing, and the remaining 60% were collected and lysed for gene expression analysis. For freshly harvested chondrocytes, 100,000 cells from each zone were collected for gene expression (P0). Mechanical and gene expression samples were collected for four passage points (P0, P1, P2, P3). Culture media were fully changed three times a week throughout the study.

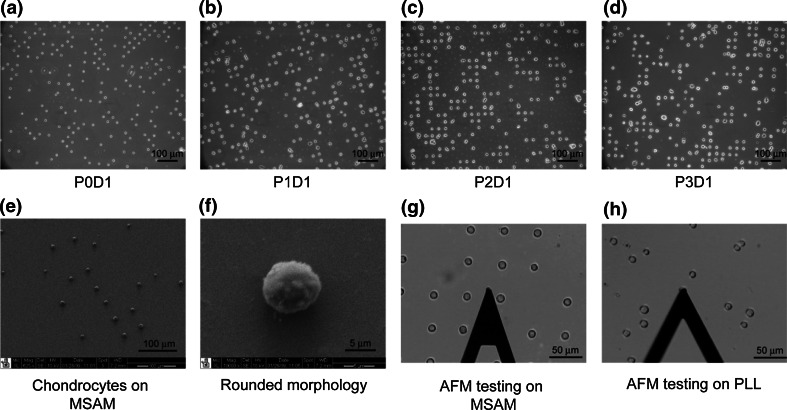

Cell Passaging for Testing on MSAMs

Primary chondrocytes from superficial and middle/deep zones were divided into three groups: 500,000 cells were plated in T75 flasks for expansion, 800,000 cells were seeded onto four MSAMs at 200,000 cells/coverslip, and 50,000 cells were lysed for gene expression analysis. For each zonal population, two MSAMs were used on Day 1 for biomechanical testing and gene analysis. This process was repeated on Day 7. When expansion cultures neared confluence, zonal chondrocytes were passaged as described previously. At each passage, 500,000 cells were re-plated in a fresh T75 flask for expansion and 800,000 cells were used to seed four new MSAMs in a manner consistent with the initial isolation and patterning procedure. Gene expressions were evaluated at Day 1 by lysing the cells on the patterned coverslips and collecting the lysate for subsequent processing. The expansion, passaging, patterning, and testing processes were repeated for three passages. MSAMs were used to restrict cell spreading to a uniform area as well as to force a spherical morphology on the seeded cells (Figs. 1a–1f).

Figure 1.

Chondrocyte culture on micropatterned self-assembled monolayers (MSAMs). Zonal chondrocytes were seeded onto MSAM surfaces after each passage, P0D1–P3D1, and cultured for 1 day before analysis (a–d). SEM images of the patterned cells indicated regular spacing (e) and a rounded morphology (f). Elastic and viscoelastic properties were measured via AFM for superficial and middle/deep zone cells on MSAMs (g) and PLL-coated polystyrene surfaces (h)

Atomic Force Microscopy

The mechanical properties of chondrocytes were measured using an atomic force microscope (MFP-3D, Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) (Figs. 1g, 1h) according to previously established techniques.11 AFM cantilevers (k ~ 0.04 N/m, Novascan Technologies, Inc., Ames, IA) were equipped with borosilicate glass spheres (5 μm diameter) and used for indentation and stress relaxation experiments on single cells. Indentations were performed over the center of the cell at 15 μm/s, chosen to approximate a step displacement appropriate for the stress relaxation model. Elastic curves were sampled at 5 kHz while viscoelastic curves were collected at 200 Hz for 60 s. A 1- to 2.5-nN force trigger was used to prescribe the point at which the cantilever approach was stopped and retracted for elastic tests or held constant for viscoelastic tests. Probe-cell contact was identified via contact point extrapolation, a method that uses the indentation portion of the approach curve to determine where probe-cell contact begins.18 The elastic modulus, E elastic, was extracted from force vs. indentation data using an appropriate thin-layer Hertz model, and E equil values were calculated from average force and indentation data at the end of the relaxation test. The parameters E R, E 0, and μ (relaxed modulus, instantaneous modulus, and apparent viscosity) were determined using a thin-layer, stress relaxation model of a viscoelastic solid.12 Following previous findings, a value of 0.38 was assumed in all calculations for the Poisson’s ratio of zonal chondrocytes.21,32,36,37

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Patterned chondrocytes were imaged using SEM to confirm cell morphologies on MSAMs (Figs. 1e, 1f). Briefly, samples were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and washed with PBS. Cells were then incubated in 1% OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 1 h and dehydrated in serial gradations of ethanol. After dehydration, the patterned cells were incubated in tetramethylsilane (TMS, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) and allowed to dry entirely. Samples were sputter coated with gold using a Desk IV sputter coater (Denton Vacuum, Moorestown, NJ) and subsequently imaged using an FEI XL30 electron scanning microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression was analyzed at each passage for zonal chondrocytes mechanically tested on PLL (superficial, middle/deep; P0, P1, P2, P3). For cells cultured on MSAMs, gene expression was analyzed for initial levels (P0D0) and Day 1 samples for the same zone/passage groups (P0D1, P1D1, P2D1, P3D1). Total RNA was isolated using the Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were lysed in the supplied lysis buffer and subsequently frozen at −20 °C. Upon thawing, ethanol was added to the homogenized lysate before the samples were purified with a spin column. Once isolated, complementary DNA was synthesized from RNA using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Total RNA and cDNA concentrations were determined by optical density measurement at 260 nm (OD260) using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop ND-1000, Wilmington, DE). Using commercially purchased primer probes from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), real-time PCR (iCycler, Bio-Rad) was used to compare transcript levels for three different genes: 18S ribosomal RNA (endogenous control; assay ID Hs99999901_s1), collagen I (COL1A1; assay ID Hs00164004_m1), and collagen II (COL2A1; custom assay: FWD primer 5-GAGACAGCATGACGCCGAG-3; REV primer 5-GCGGATGCTCTCAATCTGGT-3; probe 5-FAM-TGGATGCCACACTCAAGTCCCTCAAC-TAMRA-3).29 For each sample, qPCR was run in triplicate for each gene. Data were analyzed by determining the ratio of transcript abundance (TA) for the gene of interest (GOI) to TA for 18 s for each sample. This ratio was then normalized to the value measured for the relevant “Superficial, P0” sample.

Statistics

Past studies have shown that single-cell mechanical tests have large population variations for measured properties. To account for this, samples sizes were chosen using appropriate power analyses. For mechanical testing of cells on PLL, a sample size of n = 43–58 cells, derived from five different animals, was used for each group. For mechanical testing of cells on MSAMs, a sample size of n = 21–31 cells, derived from five different animals, was used for each group. Gene expression samples were collected from individual patterned coverslips, seeded with cells initially from five different animals, and tested in triplicate. Mechanical data were not normally distributed according to the Shapiro–Wilk test and were log-transformed before statistical analyses. Two-factor ANOVA with Newman–Keuls post hoc analysis was performed using the Statistica software package (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) to determine whether significant differences (α = 0.05) in biomechanical properties existed among passages and between zonal populations for the first experiment. Three-factor ANOVA (zone, passage, days on MSAMs) was performed for the second experiment. For graphical representations, a Dunnett post hoc test was performed to determine significance between each sample and its P0D0 control. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Mechanical Properties of Serially Expanded Chondrocytes Tested on PLL

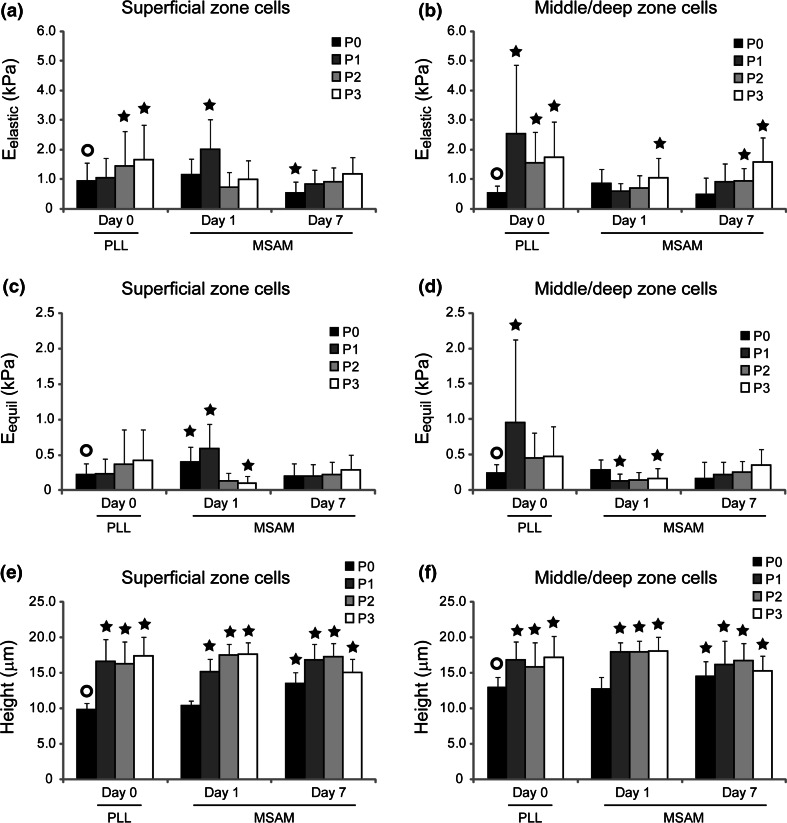

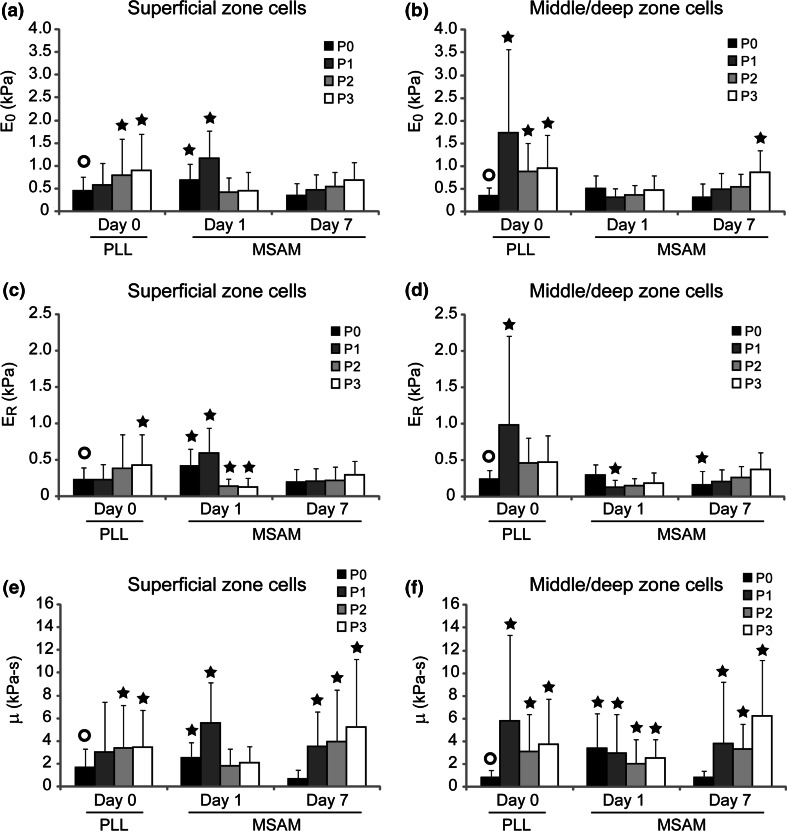

Monolayer expansion induced a significant change in the mechanical biomarkers associated with zonal chondrocytes. For superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes tested at P0–P3, E elastic values ranged from 0.53 to 2.5 kPa (Figs. 2a, 2b), E equil from 0.22 to 0.95 kPa (Figs. 2c, 2d), E 0 from 0.36 to 1.7 kPa (Figs. 3a, 3b), E R from 0.22 to 0.99 kPa (Figs. 3c, 3d), and μ from 0.86 to 5.8 kPa s (Figs. 3e, 3f). Significant differences existed for both experimental factors (zone, passage) as well as their interaction (p < 0.0001). Characteristic differences between superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes were present after initial harvest, with superficial cells exhibiting higher elastic moduli values than middle/deep cells (p < 0.0008), a correlation which held true largely independent of substrate, mechanical measure, or day. These differences rapidly disappeared with serial expansion. By P2–P3, zonal chondrocytes exhibited very similar elastic and viscoelastic properties. Concurrent with these mechanical property changes, superficial and middle/deep zone cells increased in height on the PLL substrates from 9.9 ± 0.1 and 13.0 ± 1.4 μm, respectively, to 17.4 ± 2.7 μm and 17.2 ± 2.9 μm (Figs. 2e, 2f).

Figure 2.

Elastic property changes due to monolayer expansion and MSAM culture. Mechanical property changes for E elastic (a, superficial; b, middle/deep) and E equil (c, superficial; d, middle/deep) showed an upward trend at Day 0 and Day 7 time points. For early-passage cells, zonal chondrocytes showed an ability to partially recover their mechanical phenotype if cultured for a week on restrictive MSAM surfaces. Cell heights dramatically increased after a single expansion (e, superficial; f, middle/deep) and showed minimal recovery with culture on MSAMs. Initial differences between the zonal populations disappeared by P2, with both cell types converging to a similar mechanical and morphological phenotype. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between samples and their P0D0 control (○) are indicated for each property/zone grouping (p < 0.05)

Figure 3.

Viscoelastic property changes due to monolayer expansion and MSAM culture. Superficial (a, c, e) and middle/deep (b, d, f) zone chondrocytes were mechanically tested immediately after passaging and after 1 or 7 days of culture on restrictive MSAM substrates. E 0, E R, and μ all showed an upward trend with respect to passage. As opposed to elastic property results, viscoelastic characteristics did not appear to be dramatically affected by culture on MSAM surfaces. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences between samples and their P0D0 control (○) are indicated for each property/zone grouping (p < 0.05)

Effect of MSAMs on Mechanical Properties

Zonal chondrocytes cultured on MSAMs exhibited mechanical property values in the range of 0.59–2.0 kPa for E elastic (Figs. 2a, 2b), 0.10–0.58 kPa for E equil (Figs. 2c, 2d), 0.31–1.2 kPa for E 0 (Figs. 3a, 3b), 0.12–0.54 kPa for E R (Figs. 3c, 3d), and 0.69–6.3 kPa s for μ (Figs. 3e, 3f). Significant differences were present for all experimental factors (zone, passage, days on MSAMs), including their interactions (p < 0.0001). Passaged chondrocytes cultured for one day on MSAMs showed a different trend in mechanical properties than that seen for cells tested on Day 0 (Figs. 3a, 3b). Interestingly, the Day 1 results for MSAM surfaces indicated a slight softening trend for zonal cells with respect to passage number. Relaxed and equilibrium moduli decreased significantly after three passages to approximately 20–60% of their original measured values (p < 0.05). Elastic and instantaneous moduli did not reflect this change. Apparent viscosity also remained relatively constant at Day 1 for all passages.

Chondrocytes cultured on restrictive MSAMs for 7 days showed a fairly uniform mechanical phenotype that differed from their initial characteristics. In general, elastic and viscoelastic properties were consistent across passage number at Day 7 for both superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocyte populations. Additionally, characteristic mechanical differences between zonal populations were not present at Day 7 time point comparisons. This finding held for all elastic and viscoelastic property comparisons (p > 0.10). For P0 and P1 superficial cells, elastic and viscoelastic properties at Day 7 were less than those measured at Day 1 (p < 0.0001). However, this effect was not present for P2 and P3 superficial cells. Middle/deep cells did not exhibit any dramatic changes in mechanical properties between Day 1 and Day 7 on the MSAM surface. In general, superficial cells cultured on MSAMs for a week possessed moduli ~60% their Day 1 values while middle/deep cells did not change. The disparity between zones is due in part to the higher initial properties for superficial zone cells.

Similar to the first experiment, cell height on MSAMs increased significantly from P0 to P3 (p < 0.0001, Figs. 2e, 2f). For Day 1 time points, superficial cells began with heights measuring 10.4 ± 0.7 μm and ended which heights of 17.7 ± 1.7 μm. Middle/deep cells saw a similar increase from 12.7 ± 1.7 to 17.9 ± 1.9 μm. In general, this height change occurred within a single passage, although superficial cells showed a more gradual increase over the first two passages. For Day 7 time points, an increase in cell height was observed from P0 to P1–P2, but a subsequent decrease occurred at P3 (p < 0.02). While statistically significant, these changes were generally small in magnitude. An interesting cell height change also occurred between Day 1 and Day 7 time points. For P0 and P1 superficial cells, heights increased 30 and 12%, respectively, after culture on MSAM surfaces, an effect likely caused by the in vitro culture environment. Minimal change was observed for P2 superficial cells (−3%), and a 15% decrease was measured for P3 cells. Middle/deep cells also showed an increase in height for P0 cells, with Day 7 values being 15% higher than Day 1 values. P1–P3 measurements all showed decreases in cell height (10, 6, 15%, respectively).

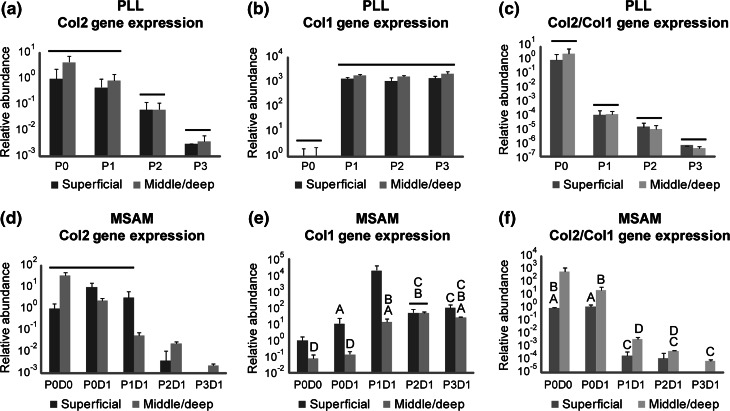

Gene Expression

Zonal chondrocytes exhibited a rapid loss of the chondrocytic phenotype over serial passages (Fig. 4). Gene expression levels for collagen I increased 102- to 103-fold after a single passage for both superficial and middle-deep zone chondrocytes (p < 0.001). Conversely, collagen II expression for both cell types decreased incrementally over serial passages to levels that were approximately 102- to 104-fold lower than P0 values (p < 0.05). Due to the inverse relationship between collagen I and II expression trends, the ratio of collagen II/collagen I gene expressions showed a dramatic 106- to 108-fold decrease from P0 to P3 (p < 0.007). These trends were observed when mRNA was collected immediately after passaging (Figs. 4a, 4b, 4c), as well as after cells had been cultured on restrictive MSAMs for one day (Figs. 4d, 4e, 4f). Insufficient cells were present on MSAMs at Day 7 for reliable gene expression analyses, so no data are shown for this time point.

Figure 4.

Loss of chondrocytic gene expression with monolayer expansion. Gene expressions for collagen II, collagen I, and the ratio of collagen II/collagen I showed dramatic changes with respect to passage for zonal chondrocytes tested immediately after passaging (a, b, c) and after 1 day in a rounded morphology on MSAM surfaces (d, e, f). All time points are normalized to their respective “Superficial, P0” data point and shown as mean relative abundance ± standard deviation. Groups not connected by bars or letters are statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Discussion

The findings of this study show that the mechanical properties of chondrocytes are altered in association with dedifferentiation and loss of phenotype that occurs with serial expansion in monolayer.6,8 These effects appear to depend on the zone of origin of the cells.13 The phenotypic and biomechanical changes occur rapidly (i.e., within one passage) and result in a more homogeneous phenotype that differs from the initial state of the cell. Superficial and middle/deep zone chondrocytes initially exhibited different elastic and viscoelastic properties but after only two passages, these differences were no longer apparent. Concurrently, zonal chondrocytes showed a loss of the chondrocytic phenotype with respect to gene expression and cell height. The loss of mechanical biomarkers occurred at a similar rate for both zonal subpopulations.

The mechanisms regulating these changes are not fully understood, but are likely interconnected, since chondrocyte mechanical properties, shape, and phenotype have all been linked to the structure of the cytoskeleton.27,38 Indeed, a relationship between the cytoskeleton and biological phenotype has been proposed in studies ranging from healthy, differentiated cells to cancer cells.22,26,27,34 In isolated chondrocytes, the cytoskeleton forms a cortical shell of F-actin.31 As chondrocytes spread, the cytoskeletal structure changes from diffuse, peripherally located fibers to large cables stretching along the entire length of the cell. Previous work by Mallein-Gerin et al. indicated that the formation of F-actin bundles in dedifferentiating chondrocytes was associated with the loss of chondrocyte phenotype as measured by collagen I expression and decreased proteoglycan synthesis.27 These findings are generally consistent with previous results showing that both the elastic and viscoelastic properties of chondrocytes are significantly altered by treatment with agents that disrupt38 or enhance24 the structure of F-actin microfilaments.

Our results suggest that the induction of a rounded morphology, using a 2D MSAM substrate, can partially ameliorate these biomechanical changes. Previous studies have shown that three-dimensional culture in a hydrogel can promote the chondrocytic phenotype.6,19,39 The mechanism underlying this effect is unclear, but may similarly entail the reorganization of the F-actin cytoskeleton. In this study, we measured collagen I and II gene expressions for dedifferentiated cells placed on MSAMs that restricted cell shape to a rounded morphology. Gene expression changes can occur rapidly in response to environmental stimuli, so it is possible that changes could be seen after only one day on a MSAM surface. However, results indicated that the chondrocytes still had abnormal expression characteristics (high collagen I, low collagen II) even in the absence of F-actin bundles, suggesting that the “redifferentiation” process may require other factors in addition to the restoration of cell shape and F-actin structure. For example, extended culture in a spherical morphology might be required to facilitate recovery of the chondrocytic phenotype. One limitation of this study was that while mechanical properties were evaluated after 7 days on these surfaces, gene expression could not be performed since the number of cells retained on the MSAM substrates after a week was insufficient for gene expression studies. Future work will investigate means to extend the culture duration of this experimental setup.

Of interest was the finding that the changes in cellular mechanical properties occurred at approximately the same rate as those for gene expression. These results suggest that alterations in mechanical biomarkers parallel the loss of cell phenotype, and thus, may provide an additional means of evaluating the differentiation state of a cell. With respect to the cells’ biomechanical phenotype, our findings showed that inducing a rounded morphology on dedifferentiated chondrocytes could partially reverse the dedifferentiated phenotype. Zonal chondrocytes cultured for 7 days on restrictive MSAMs typically exhibited mechanical properties more similar to native levels than cells cultured for only 1 day. It is possible that re-differentiation is feasible with extended culture in this setup, as observed for chondrocytes cultured in three-dimensional hydrogels.6,19,39 While current results show that cell shape induces a change in mechanical properties for dedifferentiated chondrocytes, further experiments are necessary to determine whether re-differentiation is due solely to cell morphology or a combination of factors present in three-dimensional culture environments, such as the material stiffness, binding characteristics, or ionic charge of the substrate.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants AR53448 (EMD), EB01630, AG15768, AR48182, AR50245, and EB002025 (RS) and NSF grant CMS-0507151 (RS). The authors would like to thank Drs. Ashutosh Chilkoti, Dominic Chow, David Dumbauld, and Andrés Garcia for discussions and advice on the development of micropatterned substrates. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility at Duke University for providing resources for SEM imaging.

References

- 1.Archer, C. W., J. McDowell, M. T. Bayliss, M. D. Stephens, and G. Bentley. Phenotypic modulation in sub-populations of human articular chondrocytes in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 97:361–371, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydelotte, M. B., R. R. Greenhill, and K. E. Kuettner. Differences between sub-populations of cultured bovine articular chondrocytes. II. Proteoglycan metabolism. Connect. Tissue Res. 18:223–234, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aydelotte, M. B., and K. E. Kuettner. Differences between sub-populations of cultured bovine articular chondrocytes. I. Morphology and cartilage matrix production. Connect. Tissue Res. 18:205–222, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bausch, A. R., F. Ziemann, A. A. Boulbitch, K. Jacobson, and E. Sackmann. Local measurements of viscoelastic parameters of adherent cell surfaces by magnetic bead microrheometry. Biophys. J. 75:2038–2049, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benninghoff, A. Form und Bau der Gelenkknorpel in ihren beziechungen zur funktion. I. Die modellierenden und formerhalterden Faktoren des Knorpelreliefs. Z. ges. Anat. 76:43–63, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benya, P. D., and J. D. Shaffer. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell 30:215–224, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cournil-Henrionnet, C., C. Huselstein, Y. Wang, L. Galois, D. Mainard, V. Decot, P. Netter, J. F. Stoltz, S. Muller, P. Gillet, and A. Watrin-Pinzano. Phenotypic analysis of cell surface markers and gene expression of human mesenchymal stem cells and chondrocytes during monolayer expansion. Biorheology 45:513–526, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darling, E. M., and K. A. Athanasiou. Rapid phenotypic changes in passaged articular chondrocyte subpopulations. J. Orthop. Res. 23:425–432, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darling, E. M., and K. A. Athanasiou. Retaining zonal chondrocyte phenotype by means of novel growth environments. Tissue Eng. 11:395–403, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darling, E. M., J. C. Y. Hu, and K. A. Athanasiou. Zonal and topographical differences in articular chondrocyte gene expression. J. Orthop. Res. 22:1182–1187, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darling, E. M., M. Topel, S. Zauscher, T. P. Vail, and F. Guilak. Viscoelastic properties of human mesenchymally-derived stem cells and primary osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. J. Biomech. 41:454–464, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darling, E. M., S. Zauscher, J. A. Block, and F. Guilak. A thin-layer model for viscoelastic, stress-relaxation testing of cells using atomic force microscopy: do cell properties reflect metastatic potential? Biophys. J. 92:1784–1791, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darling, E. M., S. Zauscher, and F. Guilak. Viscoelastic properties of zonal articular chondrocytes measured by atomic force microscopy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14:571–579, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans, E. E., and R. M. Hochmuth. Membrane viscoelasticity. Biophys. J. 16:1–11, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallant, N. D., K. E. Michael, and A. J. Garcia. Cell adhesion strengthening: contributions of adhesive area, integrin binding, and focal adhesion assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4329–4340, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grundmann, K., B. Zimmermann, H. J. Barrach, and H. J. Merker. Behaviour of epiphyseal mouse chondrocyte populations in monolayer culture. Morphological and immunohistochemical studies. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histol. 389:167–187, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guck, J., S. Schinkinger, B. Lincoln, F. Wottawah, S. Ebert, M. Romeyke, D. Lenz, H. M. Erickson, R. Ananthakrishnan, D. Mitchell, J. Kas, S. Ulvick, and C. Bilby. Optical deformability as an inherent cell marker for testing malignant transformation and metastatic competence. Biophys. J. 88:3689–3698, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo, S., and B. B. Akhremitchev. Packing density and structural heterogeneity of insulin amyloid fibrils measured by AFM nanoindentation. Biomacromolecules 7:1630–1636, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauselmann, H. J., M. B. Aydelotte, B. L. Schumacher, K. E. Kuettner, S. H. Gitelis, and E. J. Thonar. Synthesis and turnover of proteoglycans by human and bovine adult articular chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Matrix 12:116–129, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikai, A. A review on: Atomic force microscopy applied to nano-mechanics of the cell. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol., 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jones, W. R., H. P. Ting-Beall, G. M. Lee, S. S. Kelley, R. M. Hochmuth, and F. Guilak. Alterations in the Young’s modulus and volumetric properties of chondrocytes isolated from normal and osteoarthritic human cartilage. J. Biomech. 32:119–127, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp, M. W., and K. E. Davies. The role of intermediate filament proteins in the development of neurological disease. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 19:1–27, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, D. A., T. Noguchi, M. M. Knight, L. O’Donnell, G. Bentley, and D. L. Bader. Response of chondrocyte subpopulations cultured within unloaded and loaded agarose. J. Orthop. Res. 16:726–733, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leipzig, N. D., S. V. Eleswarapu, and K. A. Athanasiou. The effects of TGF-beta1 and IGF-I on the biomechanics and cytoskeleton of single chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14:1227–1236, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, Z., J. B. Fitzgerald, J. Xu, C. Willers, D. Wood, A. J. Grodzinsky, and M. H. Zheng. Gene expression profiles of human chondrocytes during passaged monolayer cultivation. J. Orthop. Res. 26:1230–1237, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makale, M. Cellular mechanobiology and cancer metastasis. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 81:329–343, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallein-Gerin, F., R. Garrone, and M. van der Rest. Proteoglycan and collagen synthesis are correlated with actin organization in dedifferentiating chondrocytes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 56:364–373, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConnaughey, W. B., and N. O. Petersen. Cell poker: an apparatus for stress-strain measurements on living cells. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 51:575–580, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehlhorn, A. T., P. Niemeyer, S. Kaiser, G. Finkenzeller, G. B. Stark, N. P. Sudkamp, and H. Schmal. Differential expression pattern of extracellular matrix molecules during chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Tissue Eng. 12:2853–2862, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy, C. L., and A. Sambanis. Effect of oxygen tension and alginate encapsulation on restoration of the differentiated phenotype of passaged chondrocytes. Tissue Eng. 7:791–803, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritchard, S., and F. Guilak. The role of F-actin in hypo-osmotically induced cell volume change and calcium signaling in anulus fibrosus cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32:103–111, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin, D., and K. Athanasiou. Cytoindentation for obtaining cell biomechanical properties. J. Orthop. Res. 17:880–890, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siczkowski, M., and F. M. Watt. Subpopulations of chondrocytes from different zones of pig articular cartilage. Isolation, growth and proteoglycan synthesis in culture. J. Cell Sci. 97:349–360, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suresh, S. Biomechanics and biophysics of cancer cells. Acta Biomater. 3:413–438, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tim O’Brien, E., J. Cribb, D. Marshburn, R. M. Taylor, 2nd, and R. Superfine. Chapter 16: Magnetic manipulation for force measurements in cell biology. Methods Cell Biol. 89:433–450, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trickey, W. R., F. P. Baaijens, T. A. Laursen, L. G. Alexopoulos, and F. Guilak. Determination of the Poisson’s ratio of the cell: recovery properties of chondrocytes after release from complete micropipette aspiration. J. Biomech. 39:78–87, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trickey, W. R., G. M. Lee, and F. Guilak. Viscoelastic properties of chondrocytes from normal and osteoarthritic human cartilage. J. Orthop. Res. 18:891–898, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trickey, W. R., T. P. Vail, and F. Guilak. The role of the cytoskeleton in the viscoelastic properties of human articular chondrocytes. J. Orthop. Res. 22:131–139, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Susante, J. L., P. Buma, G. J. van Osch, D. Versleyen, P. M. van der Kraan, W. B. van der Berg, and G. N. Homminga. Culture of chondrocytes in alginate and collagen carrier gels. Acta Orthop. Scand. 66:549–556, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss, L., and K. Clement. Studies on cell deformability. Some rheological considerations. Exp. Cell Res. 58:379–387, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanetti, M., A. Ratcliffe, and F. M. Watt. Two subpopulations of differentiated chondrocytes identified with a monoclonal antibody to keratan sulfate. J. Cell Biol. 101:53–59, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanetti, N. C., and M. Solursh. Induction of chondrogenesis in limb mesenchymal cultures by disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 99:115–123, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]