Abstract

Dysregulation of transformation growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling has been reported in human psoriasis. However, the causal role of TGFβ in psoriasis has not been given attention until our recent report that the transgenic mice expressing wild-type TGFβ1 in the epidermis using a keratin 5 promoter (K5.TGFβ1wt) developed psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Additional experimental data further support the causal role of TGFβ1 overexpression in psoriasis. First, we temporally induced TGFβ1 expression in keratinocytes in our gene-switch-TGFβ1wt transgenic mice and found that inflammation severity correlated with on-and-off switch of TGFβ1wt transgene expression. Second, deletion of T cells in K5.TGFβ1wt mice significantly delayed the development of psoriatic lesions. Third, therapeutic approaches effective for human psoriasis, i.e. Enbrel and Rosiglitazone (Avandia®), are also effective in relieving the symptoms seen in K5.TGFβ1wt mice. Future studies will dissect specific mechanisms and identify key factors in the TGFβ1-induced skin inflammation. Our mouse models will provide a useful tool to test novel therapeutic interventions and help to design specific therapeutic approaches for inflammatory skin disorders, including human psoriasis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease seen in dermatology clinics. The most frequently seen form of psoriasis is psoriasis vulgaris, occurring in 90% of all cases. Psoriasis vulgaris is characterized by scaly papulosquemous plaque lesions. Less common types of psoriasis including psoriatic erythroderma, pustular psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are usually thought to be more severe entities of psoriasis (Griffiths and Barker, 2007). Psoriasis is rarely life-threatening; however, it has a severe negative impact on the patient's quality of life and can be an economic burden. Therefore, research on the pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis has long been a focus in the field of cutaneous disease studies. Histologically, psoriasis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and parakeratosis, dilated and prominent blood vessels in the upper dermis, and leukocyte infiltration in dermis and epidermis (Griffiths et al., 2007;Gudjonsson et al., 2007). In line with these alterations, psoriatic keratinocytes exhibit increased proliferation and reduced differentiation. Also, studies suggest that local infiltrated T-cells and macrophages in the psoriatic lesion play a key role in the development of psoriasis through the release of numerous cytokines and chemokines. Furthermore, anti-T-cell and anti-TNF-α therapy for psoriasis patients demonstrated considerable clinical efficacy in relieving the severity and symptoms of psoriasis (Sabat et al., 2007). The accumulated evidence supports a crucial role for the immunological response in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, but the details of this mechanism still remain to be elucidated.

TGFβ signaling pathway

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is a multipotent cytokine that regulates both cell growth and differentiation. Three isoforms of TGFβ (TGFβ1, 2 and 3) have been documented in human tissues. In most cell types, all three forms share similar biological activities; TGFβ1 is the predominant isoform in the majority of tissues, including the skin. All isoforms of TGFβ are secreted in biologically latent forms, which must be activated before exerting their effect on target cells. TGFβ is activated when its C-terminal mature form is cleaved from the N-terminal latency-associated peptide (LAP) (Lawrence, 1991). The active TGFβ ligand binds to a heterodimeric receptor complex comprised of type I and type II TGFβ receptors (TGFβRI and TGFβRII). TGFβRI then phosphorylates the downstream molecular mediators Smad2 and Smad3. Phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 enter the nucleus to complex with Smad4 and regulate TGFβ responsive genes (Wrana et al., 1994). The function of TGFβ varies with its target tissue origin or cell types. Skin has been shown to be an important target tissue of TGFβ. The expression of TGFβ receptors and Smads are all detected in epidermal keratinocytes (Lange et al., 1999;Quan et al., 2002;Han et al., 2005). In the skin, TGFβ has been demonstrated to inhibit the growth of keratinocytes but stimulate the growth of fibroblasts (Pittelkow et al., 1988;Cutroneo, 2007).

Alteration of TGFβ1 in human psoriasis

In human psoriasis, there is a significant reduction of TGFβ receptors in psoriatic epidermis (Leivo et al., 1998;Doi et al., 2003). Since TGFβ1 is a potent growth inhibitor for keratinocytes, it has been suspected that reduced TGFβ signaling potentiates keratinocyte hyperproliferation in psoriasis epidermis. However, reduced TGFβ receptors could also be a result of increased TGFβ1 ligand. Increased TGFβ1 in the epidermis and the serum has been found in psoriatic patients (Flisiak et al., 2002) and the TGFβ1 serum level was closely correlated with disease severity (Nockowski et al., 2004;Flisiak et al., 2008). In contrast, TGFβ1 is barely detectable in normal skin epidermis because of its short half-life time(Wakefield et al., 1990;Wataya-Kaneda et al., 1994;Quan et al., 2002;Han et al., 2005). Successful treatment resulted in reduced serum levels of TGFβ1 in patients with psoriasis (Flisiak et al., 2003). The mechanism for increased serum levels of TGFβ1 in patients with psoriasis remains unclear. In other diseases, TGFβ1 polymorphisms significantly affect serum levels of TGFβ1 (Akhurst, 2004;Mao et al., 2006). It remains to be determined whether these polymorphisms correlate with psoriasis. The increased TGFβ1 could also come from activated endothelial cells, fibroblasts, or inflammatory cells in psoriasis patients; all of which can produce more TGFβ1 (Flisiak et al., 2008). However, based on clinical data, it is difficult to determine if increased TGFβ1 plays a causal role in psoriasis, or it is simply a consequence of psoriasis pathogenesis.

Causal Role of TGFβ1 in psoriasis pathogenesis

We developed TGFβ1 transgenic mice, in which wild-type human TGFβ1 cDNA was targeted to the epidermis using the keratin 5 (K5) promoter (K5.TGFβ1wt). In this transgenic model, latent TGFβ1 was overexpressed in the epidermis at levels similar to peak expression during cutaneous wound healing (Li et al., 2004). K5.TGFβ1wt transgenic mice surprisingly developed a severe inflammatory skin disorder mimicking the characteristics of human psoriasis both grossly and microscopically. The phenotypes of K5.TGFβ1wt mice included psoriasis-like plaques and Koebner's phenomenon around one month of age and generalized scaly erythema when skin inflammation progressed. Histologically, K5.TGFβ1wt transgenic skin developed significant epidermal hyperplasia with inflammatory cell infiltration and neovascularization. Molecular mechanism analysis showed that Th1 type cytokines including IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α predominated in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. Therefore, these mice provide a mouse model mimicking human psoriasis (Li et al., 2004).

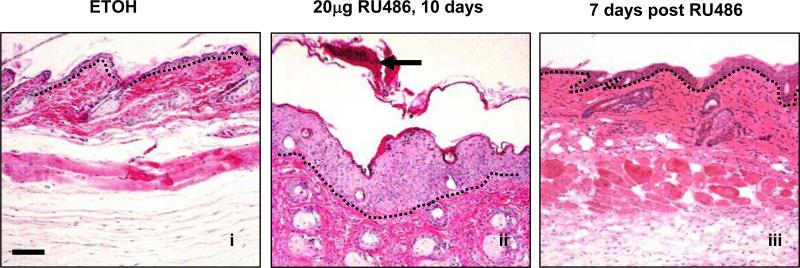

To further assess whether psoriasis phenotypes found in K5.TGFβ1wt mice represent a direct effect of TGFβ1 overexpression, we induced TGFβ1 in the epidermis in our gene-switch transgenic mice, in which transgene expression can be turned on-and-off, and the levels of transgene expression can be regulated by topical application of RU486 (Lu et al., 2004;Li et al., 2005). When RU486 was topically applied daily on dorsal skin for 10 days, scaly erythema and papules were seen on RU486-treated skin of bigenic mice, but not in control mice. Histopathology revealed that bigenic skin recapitulated pathological alterations seen in K5.TGFβ1wt skin, e.g., epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, leukocyte infiltration, and microabscesses (Fig.1). Continuous RU486 application maintained the psoriasis-like inflammation, and the phenotype severity correlated with TGFβ1 expression levels in bigenic mice (not shown). Immunostaining using antibodies against a variety of leukocyte surface markers demonstrated a similar infiltration pattern in bigenic skin to that of K5.TGFβ1wt skin. Particularly, CD4+ T cells resided in the dermis, whereas CD8+ T cells predominantly infiltrated the epidermis. Increased BM8+ macrophages and angiogenesis were also prominent in the bigenic skin as compared to control skin (not shown). Interestingly, epidermal thickness and leukocyte infiltration in bigenic skin declined dramatically one week after withdrawal of RU486 (Fig.1). This experiment provided strong evidence that psoriasis-like skin inflammation is closely correlated with TGFβ1 expression in the skin.

Fig. 1. Effects of TGFβ1wt transgene induction in gene-switch-TGFβ1wt skin.

The H&E staining of dorsal skin from TGFβ1wt gene-switch mice treated with ETOH (i) or RU486(ii) for 10 days. Epidermal hyperplasia and corneal microabscess (arrow) were noticed upon TGFβ1wt induction (ii) and recovered to normal skin after withdrawal of RU486 (iii). The bar in panel (i) represents 100μm for all sections. The dotted line in each section highlights the epidermal-dermal junction.

Deletion of T cells delays but cannot prevent TGFβ1-induced inflammation

In the past three decades, T lymphocytes have been thought to play a crucial role in the initiation and maintenance of psoriatic lesions. The evidence first came from the efficiency of cyclosporine-A therapy in relieving or clearing the lesion of psoriatic patients. Furthermore, bone marrow transplantation from a psoriatic patient to a nonpsoriatic patient could trigger psoriasis in the recipient; otherwise the psoriasis disappeared when psoriasis patients received bone morrow transplants from healthy donors. Finally, uninvolved skin of psoriatic patients grafted onto immunodeficient mice could initiate psoriatic lesions with the injection of autologous immune blood cells, but psoriasis is not initiated when a healthy skin graft was replaced in the xenograft. Moreover, a recently developed anti-T-cell biologic agent showed efficiency in relieving symptoms of psoriasis, although it is less effective than those targeting TNF-α (Gudjonsson and Elder, 2006;Sabat et al., 2007).

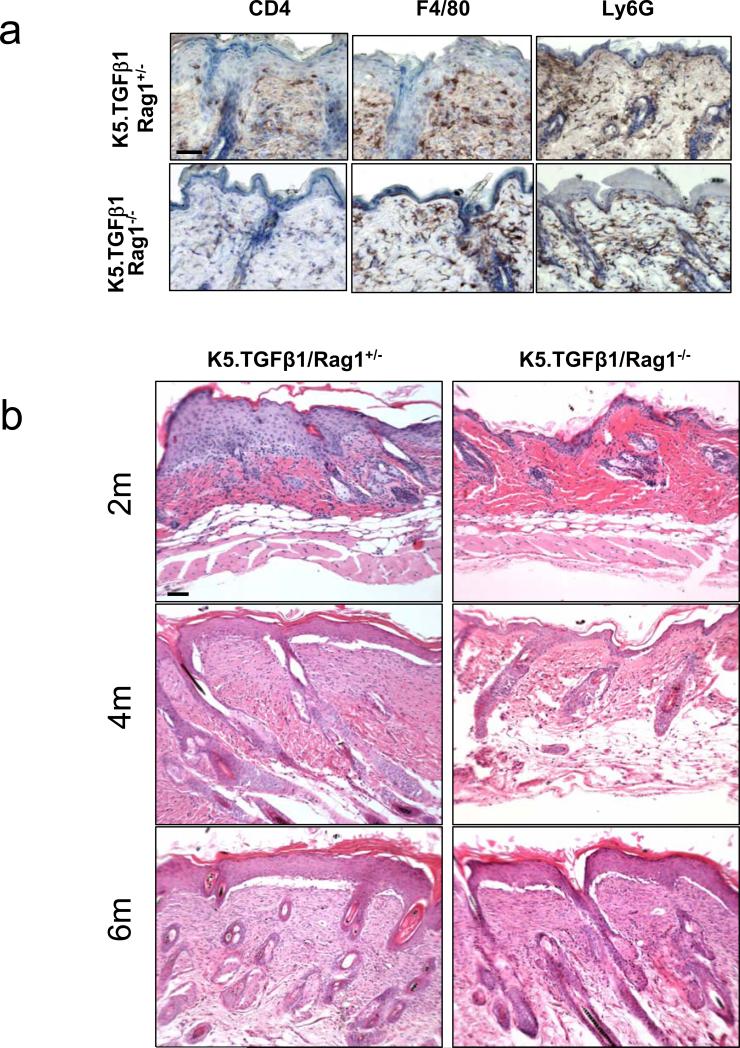

In the past, TGFβ1 was considered a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine with strong immune suppressive effects, as TGFβ1 knockout mice died of autoimmune diseases (Shull et al., 1992;Kulkarni et al., 1993). Therefore, at first glance, it is surprising that K5.TGFβ1wt mice developed psoriasis-like phenotypes. However, TGFβ1 also exerts a pro-inflammatory effect. For instance, in the skin, TGFβ1 is required for Langerhans cell development and maturation(Borkowski et al., 1996;Borkowski et al., 1997) which can trigger skin inflammation. Recently, several studies suggested that TGFβ1 is required for the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into pro-inflammatory interleukin 17-producing T helper cells (Th17 cells) (Bettelli et al., 2006;Mangan et al., 2006;Veldhoen et al., 2006;Yang et al., 2008). Th17 cells have recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and other autoimmune inflammatory disease(Wilson et al., 2007;Lowes et al., 2008;Blauvelt, 2008). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are found in large numbers in the dermis and at the dermal-epidermal junction in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. Also, Th1-type cytokines were predominant in the skin of K5.TGFβ1wt mice. These findings prompted us to determine whether infiltrated T cells contribute to TGFβ1-mediated psoriasis phenotypes. To test this hypothesis, we generated K5.TGFβ1wt mice deficient in mature T and B cells (K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/-) through cross mating K5.TGFβ1wt mice with Rag1-/- mice, which lack mature T and B lymphocytes (Mombaerts et al., 1992). Immunohistochemical staining showed CD4 positive T cells were largely depleted in the K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin, but total leukocytes (CD45+, not shown), which are mainly macrophages (F4/80) and granulocytes (Ly6G+) (Fig. 2a) in K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin were similar to K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- skin (Fig. 2a). This finding suggests that overall leukocyte infiltration was not a secondary event of T cell activation, but rather the direct chemoattractant effect of TGFβ1 on leukocyte infiltration in this model. Histologically, a significant reduction in epidermal hyperplasia and inflammation has been observed as early as 3 weeks in K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- compared to K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- littermates, and this effect is sustained over 4 months (Fig.2b). In accordance with the phenotype changes, expression levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β in skin as determined by quantitative RT-PCR were significantly decreased in K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin compared with K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- skin (not shown). However, the anti-inflammatory effect of T cell depletion was gradually lost after 6 months of age in K5.TGFβ1wt /Rag1-/- mice (Fig. 2b). The above data suggest that T cells are an important driver of the inflammation responsible for the psoriasis-like phenotype, especially at the early stage of psoriasis initializations. However, accumulated pro-inflammatory cytokines or chemokines from other inflammatory cells may be crucial in maintaining skin psoriasis-like inflammation. Similar to our current findings, a limited effect of T cells in psoriasis-like skin inflammation was also noticed in mice with JunB and C-Jun double knockout mice (Zenz et al., 2005), although it has been questioned whether this mouse model mimics human psoriasis (Gudjonsson et al., 2006;Nickoloff, 2006). Nevertheless, the limited role of T cells in the development of psoriasis was also evidenced by clinical trials showing that anti-TNF-α therapy is more effective than anti-T-cell therapy in relieving the severity and symptoms of psoriatic patients, as TNF-α producing-cells in psoriasis are not limited to T cells but also include other cells, such as monocytes and keratinocytes (Sabat et al., 2007;Thaci, 2008).

Fig. 2. T cell depletion delays TGFβ1-induced inflammation.

(a) Immunohistochemical staining for T (CD4+) cells, macrophages (F4/80+) and granulocytes (Ly6G+) in K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- and K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin. CD4+ T cells were largely depleted in the K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin. No significant difference in macrophage (F4/80+) and granulocyte (Ly6G+) staining was observed between K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- and K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- skin. (b) Histological analysis of skins from K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- and K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- mice at 2, 4, 6 months (2m, 4m, 6m) of age. Skin from K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1+/- mice shows profound inflammatory cell infiltration, epidermal hyperplasia and basement membrane degradation at 2m and 4m of age, but the phenotype was almost reversed in K5.TGFβ1wt.Rag1-/- mice. Skins from both genotypes showed similar histological alteration at 6m of age. The bar in panel (a) and (b) represents 40μm.

Therapeutic approaches effective for human psoriasis are also e ffective in K5.TGFβ1wt mice

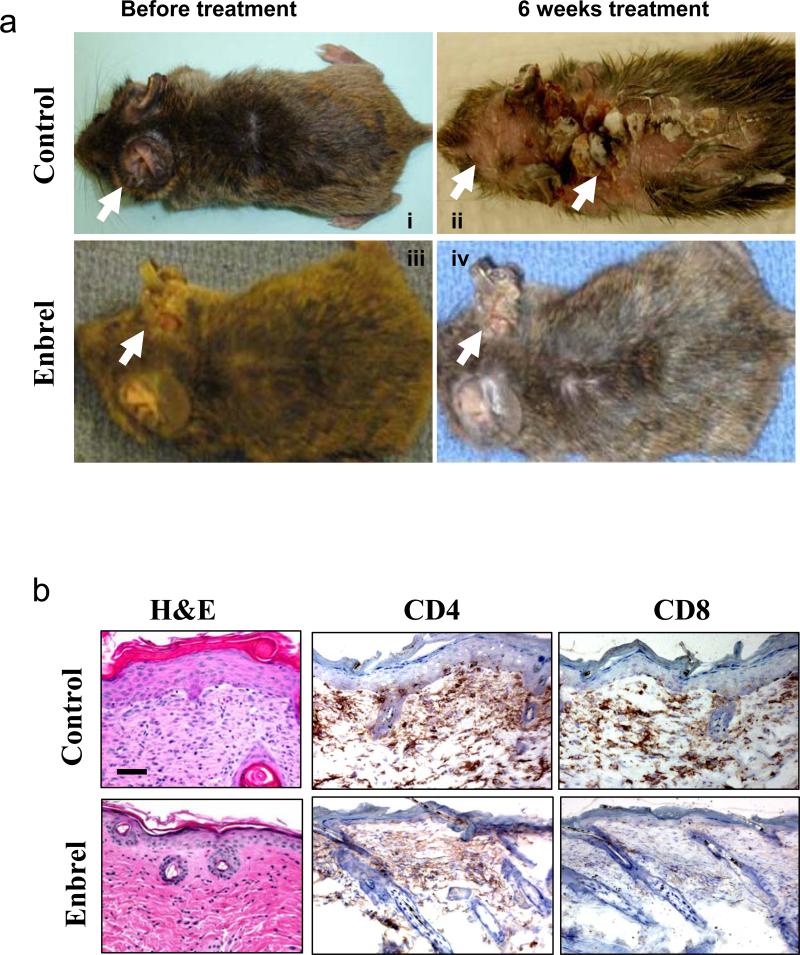

To further evaluate if K5.TGFβ1wt mice truly mimic human psoriasis pathology and therefore can be used in the future for testing therapeutic intervention, we tested two psoriasis therapeutics used clinically on K5.TGFβ1wt mice. First, we tested if Enbrel (Etanercept) could relieve the inflammation of K5.TGFβ1wt mice. Enbrel is an FDA-approved drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. It is a soluble fusion protein composed of TNF-α receptors and the Fc portion of human IgG1. Enbrel competitively binds to TNF-α, preventing TNF-α from binding to endogenous receptors, thereby blocking TNF-α mediated inflammation (Zeichner and Lebwohl, 2007). Clinical trials on human psoriasis showed that 34-49% or 44-59% psoriatic patients achieved 75% PASI score improvement when Enbrel was administrated to patients for 12-16 weeks or 24 weeks respectively (Thaci, 2008). Continuation of Enbrel treatment for up to 60 weeks results in improvement of symptoms for 63% patients (Thaci, 2008). To evaluate the therapeutic effect of Enbrel on K5.TGFβ1wt mice, mice at 6 weeks of age, when the psoriasis phenotype began to develop, were treated with Enbrel. Enbrel was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) to K5.TGFβ1wt mice at the dosage of 0.4 mg/mouse every other day for up to 6 weeks, and controls were treated with normal saline i.p. at the same time. Beginning 3 weeks after Enbrel treatment, the reduction of psoriasis phenotype was observed by histology analysis with reduced epidermal hyperplasia and fewer numbers of infiltrated T-cells by comparison with control mice (Fig. 3b). The improvements of gross appearance in Enbrel-treated mice were obvious after 6 weeks of treatment (Fig. 3a, 3b). Without treatment, the phenotype worsened as evidenced by an increased skin area covered with psoriatic plaques or psoriasis-like inflammation. In contrast, 6 weeks after Enbrel treatment, K5.TGFβ1wt mice exhibited few psoriatic plaques or only mild skin inflammation. Histology shows the treated skin exhibited a dramatic reduction in epidermal hyperplasia (Fig.3b). The results confirmed that anti-TNF-α therapy could relieve the inflammatory symptoms of K5.TGFβ1wt mice, much like the efficacy of anti-TNF-α therapy on human psoriasis.

Fig. 3. Enbrel therapy relieve the inflammatory symptoms of K5.TGFβ1wt mice.

(a) Typical gross appearances of K5.TGFβ1wt mice before and after Enbrel treatment for 6 weeks. Normal saline treated mice were used as controls. Minor skin inflammation appeared on the ear of K5.TGFβ1wt mice at the age of 6 weeks (i & iii) and progressed to spread over most of the body area with psoriatic plaques or skin inflammation at the age of 12 weeks (ii). Enbrel therapy prevented acceleration of skin phenotypes (iv). Arrows point to inflammation sites. (b) H&E staining of K5.TGFβ1wt skin sections 6 weeks with and without Enbrel treatment (left) revealed significant reduction of epidermal thickness. However, K5.TGFβ1wt skin exhibited alleviative infiltration of CD4 and CD8 T cells and mild reduction in epidermal thickness as early as 3 weeks after starting Enbrel therapy (middle and right panels). The bar in panel (b) represents 40μm.

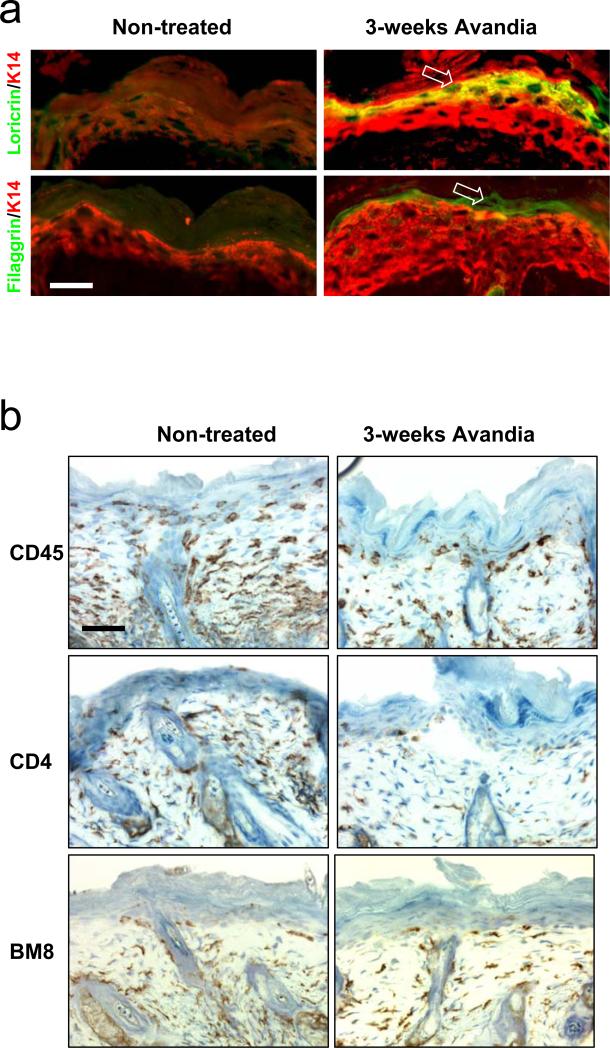

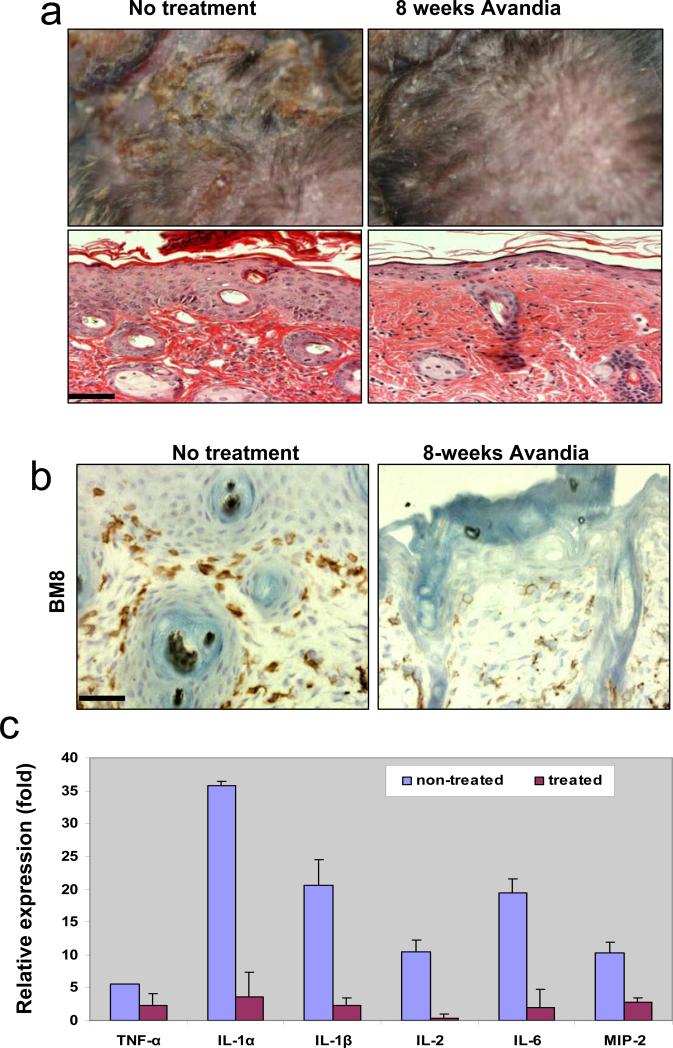

Second, we tested the efficacy of Rosiglitazone (Avandia®) on K5.TGFβ1wt mice. Avandia® is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) agonist approved for the treatment of type II diabetes mellitus. Previous studies revealed that Avandia® has properties of anti-inflammation (Pershadsingh, 2004) and antagonizing TGFβ signaling (Ghosh et al., 2004). Avandia® has also been reported to be effective in treating other diseases, such as autoimmune (e.g., multiple sclerosis), atopic (e.g., asthma, atopic dermatitis) and other inflammatory diseases (e.g., psoriasis, ulcerative colitis) (Pershadsingh, 2004). We gave Avandia® at the concentration of 0.04mg/ml in drinking water, starting 2-3 months old K5.TGFβ1wt mice or RU486-treated gene-switch-TGFβ1 mice when psoriasis-inflammation was well developed, up to 1 year of age. Transgenic littermates that received no Avandia® in drinking water were used as controls. Terminal differentiation markers of the epidermis, loricrin and fillagrin, which were lost in TGFβ1wt skin, were restored after only 3 weeks of Avandia® treatment (Fig.4a). At this stage, the gross phenotype has yet to improve (not shown). Immunostaining shows that total (CD45+) leukocytes and CD4+ lymphocytes were reduced whereas BM8+ macrophages were only slightly reduced in TGFβ1wt skin 3 weeks after Avandia® treatment (Fig.4b). With additional treatment for 8 weeks, skin inflammation including gross phenotype and histology in K5.TGFβ1wt mice improved significantly (Fig.5). For example, the lesions over treated transgenic mice were much less severe than non-treated mice, and epidermal hyperplasia was appreciatively reduced (Fig.5a). Interestingly, at this stage, in addition to a considerable reduction of T cells and leukocytes in the lesion (not shown), the number of macrophages stained by BM8 was significantly decreased in the skin of K5.TGFβ1wt mice (Fig.5b). These data further suggest that activated macrophages contribute greatly to the maintenance of TGFβ1-mediated skin inflammation. Notably, mRNA expression levels of many pro-inflammatory molecules, e.g., TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6 and MIP-2 (IL-8 homolog), which were expressed at an increased level in the skin of K5.TGFβ1wt mice, were drastically reduced after an 8-week treatment with Avandia® (Fig.5c). Since many of these inflammatory cytokines can be produced in multiple cell types, including inflammatory cells, keratinocytes and fibroblasts, it is likely that Avandia® targets more than one cell population, which appears to be more effective than depleting only T cells. Indeed, the anti-inflammatory effect of Avandia® in K5.TGFβ1wt mice persisted during treatment for up to 1 year of observation.

Fig. 4. Restoration of abnormal epidermal differentiation and reduction of lymphocytes and leukocytes in K5.TGFβ1wt mice skin after short term Avandia@ treatment.

(a) Staining of epidermal differentiation marker in K5.TGFβ1wt skin with and without Avandia@ treatment. Note that the loricrin and fillagrin lost in K5.TGFβ1wt skin reappeared (arrows) after 3 weeks Avandia@ treatment. (b) Short term Avandia@ treatment significantly reduced the infiltration of total leukocytes (CD45) and T lymphocytes (CD4), but not macrophages (BM8) in the skin from K5.TGFβ1wt mice. The bar in panel (a) and (b) represents 40μm.

Fig. 5. Attenuation of the inflammatory phenotype in K5.TGFβ1wt mice with Avandia@ treatment.

(a) K5.TGFβ1wt mice with 8-weeks of Avandia@ treatment showed a significant reduction in skin inflammation as compared to non-treated transgenic mice. H&E staining shows reduced epidermal thickness with Avandia@ treatment. (b) The number of macrophages stained by BM8 was significantly decreased in the skin of K5.TGFβ1wt mice treated with Avandia@ for 8 weeks. (c) mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were all significantly reduced (n=5, p<0.01) in the skin of K5.TGFβ1wt mice treated with Avandia@ for 8-weeks, in comparison with non-treated K5.TGFβ1wt skins. The bar in panel (a) and (b) represents 40μm.

Summary and Future directions

Although the effects of TGFβ are diversified due to its target tissue or cells-specificity, our experiments provided strong evidence that psoriasis-like skin inflammation is closely correlated with the overexpression of latent TGFβ1 in epidermis. The phenotype of K5.TGFβ1wt mice is substantially alleviated upon treatment with therapeutic approaches effective for human psoriasis, such as Enbrel or Avandia®. Also, these models will be used to test novel therapeutic intervention, particularly when considering anti-TGFβ1 as a therapeutic approach. More studies will dissect the specific mechanism of TGFβ1 induced skin inflammation; for example, the involvement of a Smad or non-Smad pathway. Furthermore, the effects of TGFβ1 on macrophages and the differentiation and activation of Th17 cells in the transgenic mice will be examined. Without a doubt, the identification of key factors mediating TGFβ1 induced inflammation will help to design specific therapeutic approaches to treat psoriasis.

Acknowledgements

The original work performed in this laboratory was supported by NIH grants to XJW. The study for the effect of Avandia® was partially supported by GSK. CW is a trainee of the NIH training grant.

Abbreviations

- TGFβ

transformation growth factor β

- TGFβRI

Type I TGFβ receptor

- TGFβRII

Type II TGFβ receptor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IL

interleukin

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- Th

T helper

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhurst RJ. TGF beta signaling in health and disease. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:790–792. doi: 10.1038/ng0804-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blauvelt A. T-helper 17 cells in psoriatic plaques and additional genetic links between IL-23 and psoriasis. J. Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1064–1067. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Farr AG, Udey MC. A role for endogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor beta 1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2417–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Mackall CL, Saitoh A, Farr AG, Wang XJ, Roop DR, Gress RE, Udey MC. Langerhans cells in the TGF beta 1 null mouse. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997;417:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutroneo KR. TGF-beta-induced fibrosis and SMAD signaling: oligo decoys as natural therapeutics for inhibition of tissue fibrosis and scarring. Wound. Repair Regen. 2007;15(Suppl 1):S54–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doi H, Shibata MA, Kiyokane K, Otsuki Y. Downregulation of TGFbeta isoforms and their receptors contributes to keratinocyte hyperproliferation in psoriasis vulgaris. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2003;33:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(03)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flisiak I, Chodynicka B, Porebski P, Flisiak R. Association between psoriasis severity and transforming growth factor beta(1) and beta (2) in plasma and scales from psoriatic lesions. Cytokine. 2002;19:121–125. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flisiak I, Porebski P, Flisiak R, Chodynicka B. Plasma transforming growth factor beta1 as a biomarker of psoriasis activity and treatment efficacy. Biomarkers. 2003;8:437–443. doi: 10.1080/13547500310001599061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flisiak I, Zaniewski P, Chodynicka B. Plasma TGF-beta1, TIMP-1, MMP-1 and IL-18 as a combined biomarker of psoriasis activity. Biomarkers. 2008;13:549–556. doi: 10.1080/13547500802033300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Lakos G, Chen SJ, Mori Y, Varga J. Disruption of transforming growth factor beta signaling and profibrotic responses in normal skin fibroblasts by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1305–1318. doi: 10.1002/art.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Mouse models: psoriasis: an epidermal disease after all? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:2–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudjonsson JE, Johnston A, Dyson M, Valdimarsson H, Elder JT. Mouse models of psoriasis. J. Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1292–1308. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han G, Lu SL, Li AG, He W, Corless CL, Kulesz-Martin M, Wang XJ. Distinct mechanisms of TGF-beta1-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis during skin carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1714–1723. doi: 10.1172/JCI24399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange D, Persson U, Wollina U, Ten Dijke P, Castelli E, Heldin CH, Funa K. Expression of TGF-beta related Smad proteins in human epithelial skin tumors. Int. J. Oncol. 1999;14:1049–1056. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence DA. Identification and activation of latent transforming growth factor beta. Methods Enzymol. 1991;198:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)98033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leivo T, Leivo I, Kariniemi AL, Keski-Oja J, Virtanen I. Down-regulation of transforming growth factor-beta receptors I and II is seen in lesional but not non-lesional psoriatic epidermis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1998;138:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li AG, Lu SL, Han G, Kulesz-Martin M, Wang XJ. Current view of the role of transforming growth factor beta 1 in skin carcinogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2005;10:110–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.200403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li AG, Wang D, Feng XH, Wang XJ. Latent TGFbeta1 overexpression in keratinocytes results in a severe psoriasis-like skin disorder. EMBO J. 2004;23:1770–1781. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes-Duculan J, Cardinale I, Zaba LC, Haider AS, Bowman EP, Krueger JG. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J. Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1207–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu SL, Reh D, Li AG, Woods J, Corless CL, Kulesz-Martin M, Wang XJ. Overexpression of transforming growth factor beta1 in head and neck epithelia results in inflammation, angiogenesis, and epithelial hyperproliferation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4405–4410. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Wahl SM, Schoeb TR, Weaver CT. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao JH, Saunier EF, de Koning JP, McKinnon MM, Higgins MN, Nicklas K, Yang HT, Balmain A, Akhurst RJ. Genetic variants of Tgfb1 act as context-dependent modifiers of mouse skin tumor susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:8125–8130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602581103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickoloff BJ. Keratinocytes regain momentum as instigators of cutaneous inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nockowski P, Szepietowski JC, Ziarkiewicz M, Baran E. Serum concentrations of transforming growth factor beta 1 in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2004;12:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pershadsingh HA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: therapeutic target for diseases beyond diabetes: quo vadis? Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:215–228. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittelkow MR, Coffey RJ, Jr., Moses HJ. Keratinocytes produce and are regulated by transforming growth factors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988;548:211–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb18809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quan T, He T, Kang S, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Ultraviolet irradiation alters transforming growth factor beta/smad pathway in human skin in vivo. J. Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:499–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabat R, Sterry W, Philipp S, Wolk K. Three decades of psoriasis research: where has it led us? Clin. Dermatol. 2007;25:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thaci D. Long-term data in the treatment of psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008;159(Suppl 2):18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakefield LM, Winokur TS, Hollands RS, Christopherson K, Levinson AD, Sporn MB. Recombinant latent transforming growth factor beta 1 has a longer plasma half-life in rats than active transforming growth factor beta 1, and a different tissue distribution. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;86:1976–1984. doi: 10.1172/JCI114932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wataya-Kaneda M, Hashimoto K, Kato M, Miyazono K, Yoshikawa K. Differential localization of TGF-beta-precursor isotypes in normal human skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1994;8:38–44. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(94)90319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Basham B, Smith K, Chen T, Morel F, Lecron JC, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ, McClanahan TK, Bowman EP, de Waal MR. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Wieser R, Ventura F, Massague J. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-beta receptor. Nature. 1994;370:341–347. doi: 10.1038/370341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher-Allan C, Hastings WD, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK, Hafler DA. IL-21 and TGF-beta are required for differentiation of human T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;454:350–352. doi: 10.1038/nature07021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeichner JA, Lebwohl M. Potential complications associated with the use of biologic agents for psoriasis. Dermatol. Clin. 2007;25:207–13. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zenz R, Eferl R, Kenner L, Florin L, Hummerich L, Mehic D, Scheuch H, Angel P, Tschachler E, Wagner EF. Psoriasis-like skin disease and arthritis caused by inducible epidermal deletion of Jun proteins. Nature. 2005;437:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nature03963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]