Abstract

ORF73, which encodes the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), is a conserved gamma-2-herpesvirus gene. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) LANA (mLANA) is critical for efficient virus replication and the establishment of latent infection following intranasal inoculation. To test whether the initial host immune response limits the capacity of mLANA-null virus to traffic to and establish latency in the spleen, we infected type I interferon receptor knockout (IFN-α/βR−/−) mice via intranasal inoculation and observed the presence of viral genome-positive splenocytes at day 18 postinfection at approximately 10-fold-lower levels than in the genetically repaired marker rescue-infected mice. However, no mLANA-null virus reactivation from infected IFN-α/βR−/− splenocytes was observed. To more thoroughly define a role of mLANA in MHV68 infection, we evaluated the capacity of an mLANA-null virus to establish and maintain infection apart from restriction in the lungs of immunocompetent mice. At day 18 following intraperitoneal infection of C57BL/6 mice, the mLANA-null virus was able to establish a chronic infection in the spleen albeit at a 5-fold-reduced level. However, as in IFN-α/βR−/− mice, little or no virus reactivation could be detected from mLANA-null virus-infected splenocytes upon explant. An examination of peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) following intraperitoneal inoculation revealed nearly equivalent frequencies of PECs harboring the mLANA-null virus relative to the marker rescue virus. Furthermore, although significantly compromised, mLANA-null virus reactivation from PECs was detected upon explant. Notably, at later times postinfection, the frequency of mLANA-null genome-positive splenocytes was indistinguishable from that of marker rescue virus-infected animals. Analyses of viral genome-positive splenocytes revealed the absence of viral episomes in mLANA-null infected mice, suggesting that the viral genome is integrated or maintained in a linear state. Thus, these data provide the first evidence that a LANA homolog is directly involved in the formation and/or maintenance of an extrachromosomal viral episome in vivo, which is likely required for the reactivation of MHV68.

Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) is a natural rodent pathogen in the Rhadinovirus subfamily of gammaherpesviruses. Other members of this subfamily include the well-studied primate pathogen herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) and the important human virus Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (or human herpesvirus 8 [HHV-8]). These viruses are characterized by a biphasic life cycle: an acute phase of virus replication, amplification at the site of initial infection and spread to distal sites, followed by the establishment of quiescent infection (latency) that is sustained throughout the life of the host (25, 54). At various times, perhaps spontaneously or in response to certain stimuli, herpesviruses are capable of exiting latency and reentering the virus replication cycle, a process termed reactivation (33, 65, 69). There are a few genes expressed during latency, and they are not always present, depending on the time point, cell type, and host, implying that different genes are needed at different stages of latency (50, 51, 77). Some of these latency genes, most notably the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) encoded by ORF73 of rhadinoviruses (57), are robustly expressed in malignancies associated with the virus (11, 31, 59, 67, 75).

LANA is transcribed as an immediate-early (IE) gene during lytic replication and is detectable in replicating infected cells both in culture with KSHV and in vivo in mice infected with MHV68 (51, 70). In addition, LANA is detectable in every KSHV-associated malignancy (56). Thus, it seems that LANA proteins have key functions in every aspect of the rhadinovirus life cycle. Indeed, MHV68 has borne out several findings not afforded in tumor studies with other gammaherpesviruses, including the findings that MHV68 LANA (mLANA) is required for the establishment of latency after intranasal infection, that mLANA-null virus can vaccinate against wild-type (wt) infection, and that mLANA is necessary for efficient lytic replication both in the lungs of mice and in tissue culture (27, 29, 52). MHV68 has also been used to map the mLANA transcript in vivo, which is quite distinct from the KSHV LANA promoter identified from tumor cell lines (1, 13, 23, 44).

Perhaps the most well-known proposed function of LANA proteins is that of episomal maintenance. The data show that LANA is necessary to maintain an HVS minigenome as a circular, extrachromosomal plasmid when introduced into replicating cells under selection. The absence of LANA led to a loss of detectable episomal minigenomes (15). Similar data have been generated for KSHV as well (4, 5). Furthermore, it was proposed that the mechanism for this maintenance is through physically tethering the viral episome to host histones so that episomes are distributed evenly to daughter cells (6, 16). Given the variety of contexts in which LANA is transcribed during the virus life cycle, it is clear that LANA homologs also have other important functions during the rhadinovirus life cycle. These other functions include manipulating the DNA damage response and other tumor suppressor pathways (27, 45, 75), transcriptional regulation (32, 58), and loading origins (36, 40, 73).

Previously, we (52) and others (30) reported the inability of mLANA-null MHV68 mutants to establish latency following the intranasal inoculation of wild-type mice. Here we report studies demonstrating that either altering the route of inoculation in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice or intranasal inoculation of type I interferon receptor knockout (IFN-α/βR−/−) mice with an mLANA-null MVH68 mutant (73.Stop) results in animals becoming persistently infected and harboring viral genome-positive splenocytes for at least 6 months postinfection. These studies also revealed an essential role for mLANA in virus reactivation from splenocytes and a critical role in peritoneal exudate cells (PECs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and viruses.

MHV68 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-derived strains 73.Stop and 73.MR were described previously (52). Briefly, 73.Stop contains two stop codons and a frameshift early in the open reading frame to disrupt mLANA expression; 73.MR rescues 73.Stop to the wild-type sequence. Viral stocks were grown to passage two in Vero-Cre cells, and titers were determined by plaque assay on NIH 3T12 monolayers.

NIH 3T12 and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine (complete DMEM). Cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 tissue culture incubator at 37°C. MEFs were obtained from C57BL/6 mouse embryos as described previously (78). Vero-Cre cells were a gift from David Leib. Cells were passaged in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 300 μg of hygromycin B/ml.

Mice and infections.

Female C57BL/6 mice 6 to 8 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, and 129S2/SvPas.IFN-α/βR−/− mice were bred and maintained at Emory University. Mice were sterile housed and treated according to the guidelines of the Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta, GA). Mice were infected intraperitoneally with 1,000 PFU of virus diluted into 0.5 ml of complete DMEM or intranasally with 100 PFU of virus diluted into 20 μl complete DMEM.

LD analyses.

Limiting-dilution (LD) assays for the frequency of latent infection were performed as previously described (78, 80). To determine the frequency of cells harboring latent viral genomes, single-copy-sensitive nested PCR was performed. Splenocytes or PECs were plated in 3-fold serial dilutions in a background of 104 NIH 3T12 cells in 96-well plates. Cells were lysed by protease K digestion for 6 h at 56°C. Two rounds of nested PCR were performed per sample with 12 samples per dilution, and the products were resolved on 2% agarose gels. To measure the frequency of reactivating cells, splenocytes or PECs were resuspended in complete DMEM and plated in serial 2-fold dilutions on MEF monolayers in 96-well tissue culture plates. Parallel samples of mechanically disrupted cells were plated to detect preformed infectious virus. Wells were scored for cytopathic effects 14 to 21 days postexplant.

Isolation of splenocytes and peritoneal cells and purification of B cells.

Mice were sacrificed by asphyxiation at the specified days. Peritoneal cells were recovered by injecting 10 ml DMEM (without serum) into the peritoneal cavity, agitating the mouse, and recovering DMEM by using a 16-gauge needle. Spleens were Dounce homogenized into a single-cell suspension, and erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride. B cells were enriched from total splenocytes by using magnetic beads (Miltenyi B-cell isolation antibody cocktail) and an AutoMACS instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

RNA was harvested from splenocytes by lysing in TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Three micrograms of RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen), and 1.5 μg of DNase-treated RNA was reverse transcribed by use of random-hexamer-primed RNA and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Minus-RT controls were performed in parallel. The resulting cDNA was serially diluted to 1/5 and 1/25. For PCR amplification of transcripts, 1 μl of each cDNA dilution was subjected to nested PCR in a 25-μl reaction mixture using primer sets previously described (1, 22, 52, 77). The PCR program was as follows: 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. Two microliters of the product from round 1 was put into a 50-μl reaction mixture from round 2 under the same conditions for 45 cycles.

BAC transfections.

NIH 3T12 cells were plated and transfected the next day with 0.5 μg BAC DNA with Superfect (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection efficiency was monitored by the expression of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) IE promoter-driven green fluorescent protein (GFP) cassette engineered into the BAC. At 3, 7, and 9 days posttransfection, supernatants were harvested, and titers were determined by plaque assay.

Immunoblot analyses.

Cells were lysed with alternative radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4 supplemented with complete mini-EDTA-free protease inhibitors [Roche]) and quantitated by using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay prior to the resuspension of 45 μg of protein in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were heated to 100°C for 10 min and were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Resolved proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose and were identified with the indicated antibodies. Immobilized antigen and antibody were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) and ECL reagents (Amersham/GE Healthcare) and were exposed to film.

Plaque assay.

Plaque assays were performed as previously described (78). NIH 3T12 cells were plated in six-well plates 1 day prior to infection at 2 × 105 cells per well. Organs were subjected to 4 rounds of mechanical disruption of 1 min each by using 1.0-mm zirconia-silica beads (Biospec Products, Bartsville, OK) in a Mini-Beadbeater-8 instrument (Biospec Products). Serial 10-fold dilutions of organ homogenate were plated onto NIH 3T12 monolayers in a 200-μl volume. Infections were performed for 1 h at 37°C with rocking every 15 min. Immediately after infection, plates were overlaid with 1.5% methylcellulose in complete DMEM. After 6 to 7 days, cells were stained with 0.12% (final concentration) Neutral Red. The next day, methylcellulose was aspirated, and plaques were counted. The sensitivity of the assay is 50 PFU/organ.

DC-PCR.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was prepared from splenocytes using standard overnight proteinase K digestion followed by phenol-chloroform extraction. Six micrograms of gDNA was digested overnight with EcoRI or BamHI in a 100-μl reaction mixture. Enzymes were inactivated and DNA was purified by using GeneCleanII (Bio 101). A total of 10%, 1%, or 0.1% of the digested DNA was placed into a 100-μl ligation reaction mixture overnight at 16°C, with or without 2 μl T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). Following ligation, a nested PCR was performed by using the following primer sets: DCTR-Bam-Lout (5′-CTCTCAACTAACACTAACAGAGGATTT-3′), DCTR-Bam-Rout (5′-ATGTCTACACCTACATGCCCGCATC-3′), DC64-Bam-Lout (5′-CAACCACAGAATATAACACCCATCTACTG-3′), and DC64-Bam-Rout (5′-TGATTTTTGCTGGAATTGCACCTG-3′) for round 1 and DCTR-Bam-Lin (5′-GGCTTTGTGGTCGTTCACACCTC-3′), DCTR-Bam-Rin (5′-TAGCGCCACCATGGTGGTAAACAA-3′), DC64-Bam-Lin (5′-AACCAGTCCCCAACTGAAAGAACG-3′), and DC64-Bam-Rin (5′-ATTGCTGTAAGCATGTAATTAATA-3′) for round 2. Probes spanning the junctions were made from the following oligonucleotides that span the junctions created by the digestion/ligation protocol: DCTR-Bam-Probe (5′-TGCCTGGCTTTTATCGTGTTCGAACCACCGTTAACTGTGAAATTGTAGAC-3′) and DC64-Bam-Probe (5′-TGGAAATCACAGTTGCAAGAACTTGAGGAGGCTGTCAAAACTACTACACA-3′). The probes were 5′ labeled with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Gels with digestion-circularization PCR (DC-PCR) products were transferred onto nylon membranes and hybridized overnight at 42°C in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 0.02% Ficoll, 15 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 10% dextran sulfate, 0.01% denatured salmon sperm DNA, and labeled oligonucleotide. Membranes were washed in 2× SSC-0.2% SDS and visualized with a Typhoon phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Statistical analyses.

All data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism software. Titer data were statistically analyzed by using the unpaired t test. The frequencies of reactivation and genome-positive cells were statistically analyzed by using the paired t test. To accurately obtain the frequency for each limiting dilution, data were subjected to nonlinear regression (using a sigmoidal dose curve with a nonvariable slope to fit the data). Frequencies of reactivation and genome-positive cells were obtained by calculating the cell density at which 63.2% of the wells scored positive for reactivating virus based on a Poisson distribution.

RESULTS

Innate immunity prevents dissemination of mLANA-null virus from the lung.

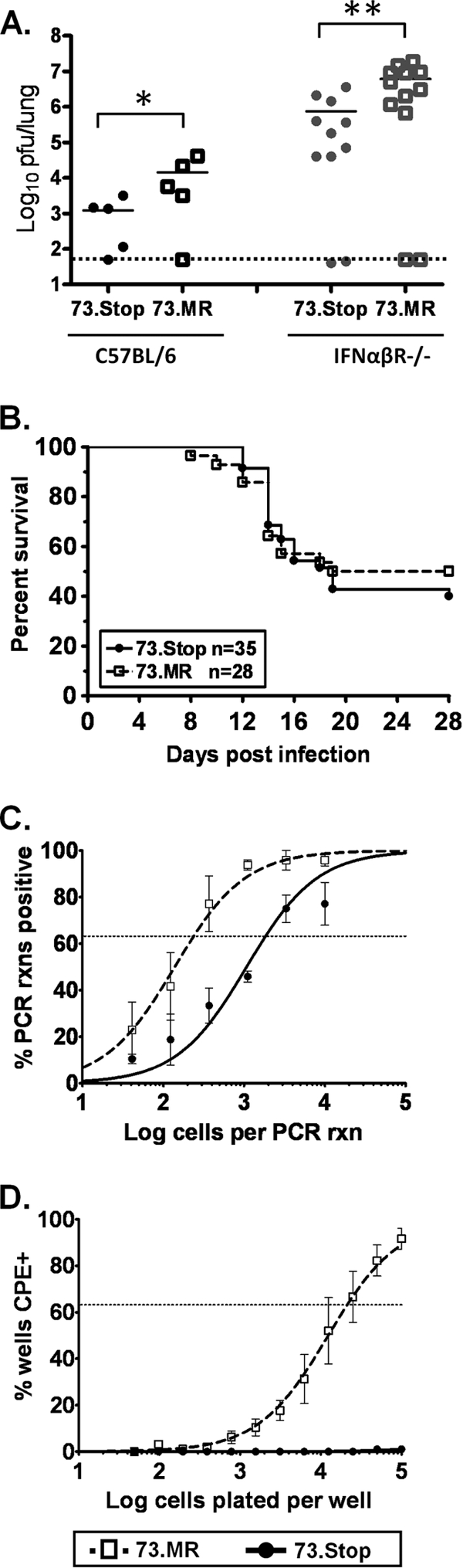

Previous studies with mLANA-deficient viruses demonstrated that mLANA is required for the establishment of latency following intranasal inoculation (30, 52). Notably, a 1- to 2-log defect in acute virus replication in the lung was also observed following intranasal inoculation (52). More recently, a replication defect was also observed in vitro at low multiplicities of infection of mouse embryo fibroblasts with an mLANA-null virus (27). Because we do not have a clear understanding of the relationship between the levels of acute virus replication in the lungs and the establishment of latency at distal sites, we initially set out to assess whether innate immunity, specifically the type I interferon response, might be involved in limiting the spread of mLANA-null MHV68 from the lung to the spleen. Type I interferon receptor knockout (IFN-α/βR−/−) and Stat1 knockout mice were previously shown to be hypersusceptible to MHV68 infection (7, 79). Thus, we inoculated IFN-α/βR−/− mice with 100 PFU of an mLANA-null virus (73.Stop) or a genetically repaired marker rescue virus (73.MR) intranasally and harvested lungs at day 9 postinfection to assess acute virus replication and spleens at day 28 postinfection to assess the establishment of latency (Fig. 1). Notably, the lack of type I interferon-mediated control of replication did not ameliorate the difference in the acute replication of 73.Stop and 73.MR, although significantly more virus production was observed in the lungs of interferon-nonresponsive animals (Fig. 1A). In addition, about half of the IFN-α/βR−/− mice succumbed to 73.Stop or 73.MR infection between days 10 and 20 postinfection, with the greatest drop at day 14 (Fig. 1B). Importantly, no differences in the kinetics of virus-induced death or the percentage of mice that survived were observed between mice infected with 73.Stop and those infected with 73.MR (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Intranasal infection of IFN-α/βR−/− mice with 73.Stop allows greater lytic replication and mLANA-independent seeding of latency in the spleen but not the reactivation of the virus. (A) Either C57BL/6 mice (black symbols) or IFN-α/βR−/− mice (gray symbols) were infected intranasally with 100 PFU of 73.Stop or 73.MR virus. Lungs were harvested 9 days later, and infectious virus titers were determined by plaque assay. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of IFN-α/βR−/− mice infected intranasally with 73.Stop or 73.MR virus. Chi-squared analysis revealed no significant difference in survival between these experimental groups. (C and D) Surviving IFN-α/βR−/− mice infected with either 73.Stop or 73.MR virus were sacrificed at day 28 postinfection, and the spleen was harvested for analysis. Splenocytes were subjected to limiting-dilution analyses to determine the frequency of cells harboring the viral genome (C) or spontaneously reactivating virus upon explant onto monolayers of mouse embryo fibroblasts (D). rxns, reactions; CPE, cytopathic effect.

To assess the establishment of latency in the spleen, we waited for lytic replication to clear, which takes 7 to 10 days longer for IFN-α/βR−/− mice (7). Of the mice that survived, spleens were harvested at day 28 postinfection and subjected to limiting-dilution PCR (LD-PCR) (Fig. 1C) and ex vivo reactivation analyses (Fig. 1D). These analyses revealed that 73.Stop can establish infection in splenocytes at a 7.7-fold-reduced frequency compared to 73.MR. However, no virus reactivation upon the explant of splenocytes from 73.Stop-infected IFN-α/βR−/− mice could be detected (Fig. 1D). This raised the question of whether we were detecting some form of detective/nonproductive 73.Stop virus infection in the spleens of IFN-α/βR−/− mice. Thus, to further address 73.Stop virus infection, we focused on infection of immunocompetent C56BL/6 mice.

Intraperitoneal inoculation of immunocompetent mice overcomes the requirement for mLANA to establish a chronic infection but reveals a role for mLANA in virus reactivation.

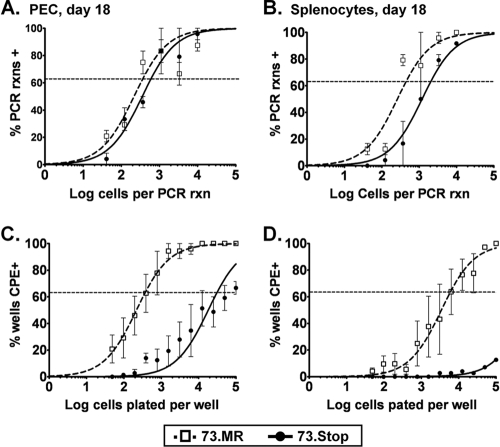

To extend the analyses of IFN-α/βR−/− mice, we investigated alternative routes of inoculation with 73.Stop virus in immunocompetent mice in an effort to overcome any restriction that virus replication in the lungs may have had on the establishment of latency. We inoculated C57BL/6 mice intraperitoneally with 1,000 PFU of either 73.Stop or 73.MR. Eighteen days postinfection, the mice were sacrificed, and peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) and spleens were harvested. LD-PCR revealed that the 73.Stop mutant established infection in both PECs and splenocytes, exhibiting 1.6-fold- and 4.6-fold-reduced frequencies, respectively, of viral genome-positive cells compared to the marker rescue virus (Fig. 2 A and B). In parallel, we assessed the capacity of splenocytes and PECs harvested from 73.Stop-infected mice to reactivate virus by plating live cells onto MEF monolayers in a limiting-dilution analysis. The 73.Stop-infected PECs demonstrated a significant, almost 2-log, decrease in the frequency of cells reactivating virus compared to PECs recovered from 73.MR-infected mice (Fig. 2C). Based on the frequency of infected cells and the frequency of reactivating cells, this means that nearly 100% of 73.MR-infected PECs reactivate virus, while only a small fraction of 73.Stop-infected PECs (1 in 51) spontaneously reactivated upon explant. Even more profound was the reactivation defect observed with splenocytes (Fig. 2D). While the frequency of splenocytes from 73.MR-infected mice that reactivated virus upon explant (1 in 5,902) was similar to that previously reported for wt MHV68, little or no virus reactivation was observed with splenocytes recovered from 73.Stop-infected mice (Fig. 2D). Attempts to stimulate 73.Stop reactivation using lipopolysaccharide (LPS) did not increase the frequency of reactivating splenocytes (C. R. Paden and S. H. Speck, unpublished observation), further highlighting this defect.

FIG. 2.

mLANA is required for efficient reactivation, but not establishment of latency, in PECs and splenocytes following intraperitoneal inoculation of immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice. Groups of three to five female C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1,000 PFU of 73.Stop or 73.MR virus. At day 18 postinfection, PECs (A and C) and splenocytes (B and D) were harvested and assayed for latency and reactivation by limiting-dilution analyses. Results are the means of data from four independent experimental groups, and error bars represent standard deviations between separate groups.

B cells are the major cell type harboring mLANA-null virus in the spleen, where it establishes an infection that persists for more than 6 months.

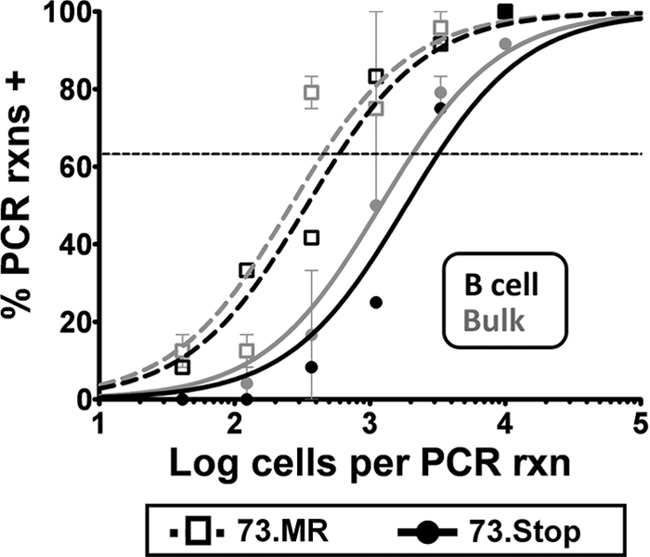

Because there are many aspects of the early establishment of latency that we do not yet understand, we asked whether there were any gross differences in the cell types that have the capacity to be latently infected in the absence of mLANA. To do this, we enriched for B cells from the spleens of mice infected with 73.Stop and 73.MR at day 18. We determined the frequency of infected B cells, using purified B cells (average, 90% purity), by LD-PCR and in parallel with analyses of the bulk unsorted populations. As expected, these analyses revealed that 73.Stop does indeed establish a chronic infection in B cells (Fig. 3) at a frequency essentially equivalent (4.5-fold decrease versus 5.4-fold decrease) to that determined for the respective unsorted splenocytes. Thus, these results demonstrate that the majority of virus infection for both 73.Stop and 73.MR viruses is in B cells, arguing against the persistence of the mLANA-null virus in a cell population that is physiologically irrelevant for the maintenance of chronic wt MHV68 infection.

FIG. 3.

B cells account for the majority of mLANA-null virus-infected splenocytes. Splenocytes were harvested from mice at day 18 postinfection and sorted into B-cell and non-B-cell populations by using a commercially available magnetic-bead-based B-cell purification kit (Miltenyi). The bulk and B-cell-positive splenocyte populations were then analyzed by limiting-dilution PCR analysis to determine the frequency of viral genome-positive cells. Purified B cells are shown as black symbols and lines, and the B-cell-depleted splenocyte population is shown as gray symbols and lines.

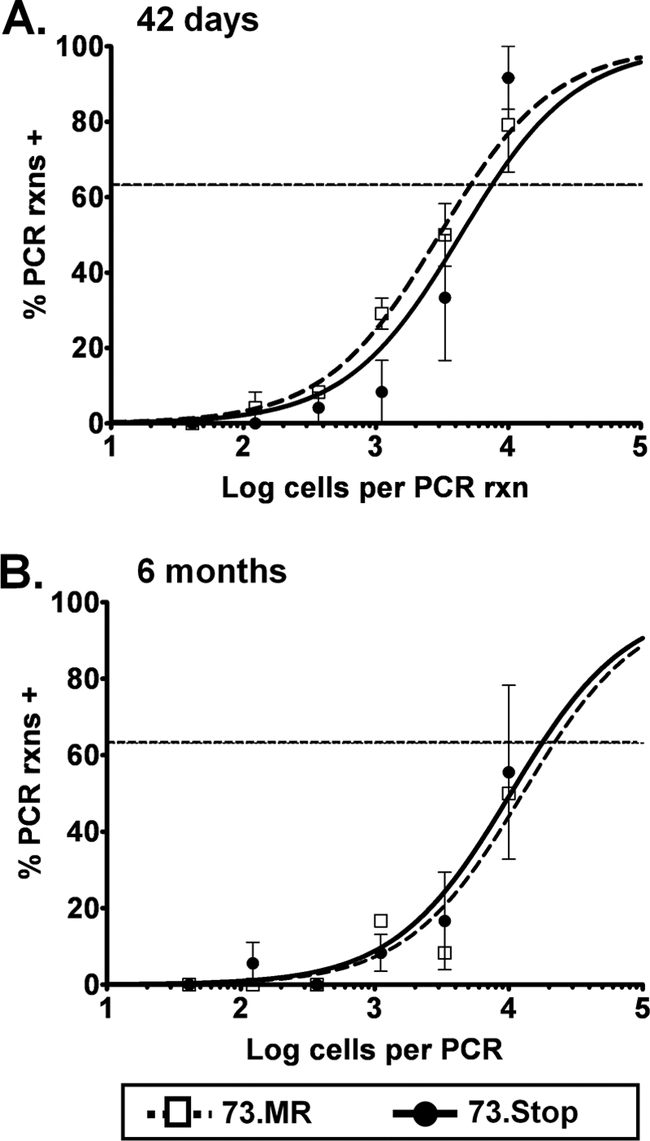

One of the many functions proposed for KSHV LANA is that of the episomal maintenance protein, which is responsible for the faithful partitioning of KSHV latent episomes to daughter cells during cell division. Fitting with this idea, we hypothesized that in the absence of mLANA, long-term MHV68 latency would not be maintained. To test this, we again infected C57BL/6 mice intraperitoneally with 73.MR or 73.Stop and sacrificed groups of mice at 6 weeks and 6 months postinfection. Unexpectedly, we observed that the frequencies of 73.Stop and 73.MR rescue viruses were equivalent at both time points (Fig. 4), demonstrating that the absence of mLANA did not lead to a loss of virus-infected splenocytes. Instead, the frequency of 73.MR-infected cells decreased to an often observed set point (71), around 1/5,000 at 6 weeks (Fig. 4A) and 1/19,000 at 6 months (Fig. 4B), where frequencies of 73.Stop-infected splenocytes also settled. This was very surprising given our previous observation that the majority of MHV68-infected B cells in the spleen are actively proliferating at 6 weeks postinfection (53) and suggests that an mLANA-independent mechanism must be involved in maintaining the viral genome.

FIG. 4.

Viral genomes are maintained long-term in mice in the absence of mLANA. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1,000 PFU of the indicated virus. At 42 days (A) and 6 months (B) postinfection, mice were sacrificed, and splenocytes were assayed by limiting-dilution PCR for the frequency of cells harboring the viral genome.

Detection of viral transcripts in splenocytes infected with mLANA-null virus.

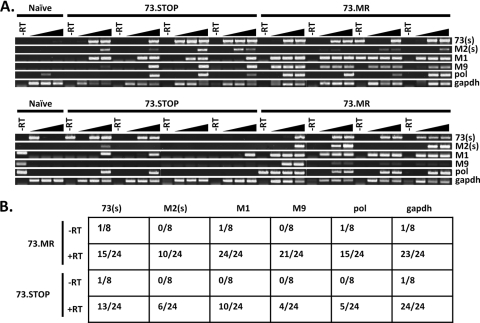

Characteristics of latent gammaherpesvirus infection include a limited expression of viral antigens, the absence of infectious virus, the capacity to reactivate, and the distinct expression of a very limited repertoire of viral transcripts (50, 66, 77). We assessed whether the 73.Stop virus-infected splenocytes express other known latency-associated viral genes in vivo. Three genes transcribed during early latency, at least in some splenocyte populations, are the unique M2 and M9 genes and ORF73 (encoding mLANA) (1, 22, 28, 60). To demonstrate an active form of latency in the absence of mLANA expression, we isolated RNA from spleens of individual mice between 25 and 28 days postinfection with 73.Stop or 73.MR and reverse transcribed it to make cDNA. To understand how levels of transcripts vary between 73.Stop and 73.MR, we assayed 5-fold serial dilutions of cDNA. PCR analysis of cDNA detected both spliced M2 and orf73 transcripts as well as M9, M1, and viral DNA polymerase transcripts in 73.MR- and 73.Stop-infected splenocytes (Fig. 5 A). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used as a control for integrity for RNA, while RNA prepared from a naïve mouse was used as a control for the specificity of RT-PCR amplification. These results demonstrate that the mLANA-null virus, although crippled for reactivation, is transcriptionally active, expressing both viral genes that are implicated in latency as well as transcripts that are upregulated during virus reactivation/replication. However, although orf73 transcripts are present, the mLANA protein is not made in the 73.Stop-infected cells.

FIG. 5.

Latency-associated MHV68 transcripts can be detected in mLANA-null virus-infected splenocytes. (A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of MHV68 latency-associated gene expression in 73.Stop- and 73.MR-infected splenocytes. RNA from individual spleens was reverse transcribed, and dilutions (undiluted or 1:5 or 1:25 dilutions) of the cDNA from each spleen were analyzed by PCR for the indicated genes. Shown are amplifications of products arising from spliced M2 or orf73 transcripts (these RT-PCR products cross the known splice junctions in these viral transcripts), M9, viral DNA polymerase (pol), M1, or the cellular GADPH transcript using RNA harvested from infected mice at days 25 to 28 postinfection. (B) Compiled data from the RT-PCR analyses shown above (A) indicating the number of PCR-positive reactions and the total number of reactions analyzed.

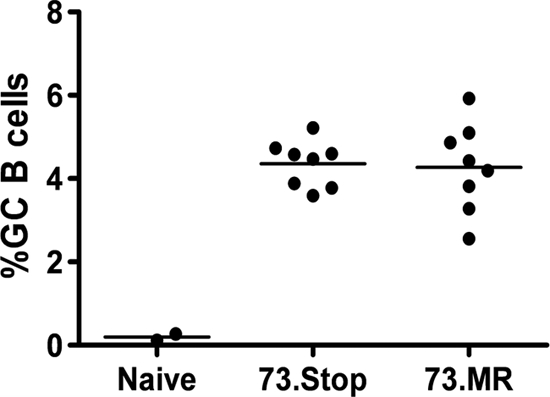

Finally, we assessed whether the initial virus-induced B-cell responses were similar between 73.Stop and 73.MR infections, since this might impact the frequency of latently infected splenocytes. MHV68 elicits a potent germinal center response, which is dependent on M2 expression (A. M. Siegel and S. H. Speck, unpublished observation). We obtained splenocytes from infected mice at day 18 postinfection and determined the frequency of CD19+ B cells that stained positive for the germinal center markers GL7 and CD95. As expected, we observed that 73.Stop and 73.MR generated similar germinal center responses: ca. 4.5% of splenic B cells harvested from either 73.Stop- or 73.MR-infected mice exhibited a germinal center phenotype, compared with ca. 0.25% of B cells harvested from naïve mice (Fig. 6). These data argue against the defect in the establishment of 73.Stop latency in the spleen being linked to a diminished germinal center response.

FIG. 6.

mLANA-deficient virus is not impaired in the induction of a strong germinal center response. Shown are compiled data from flow cytometry analyses of the germinal center (GC) response (expressed as a percentage of total B cells that exhibit a germinal center phenotype) in the spleen at 18 days postinfection. Splenocytes from individual mice were stained with anti-CD19, GL7, and anti-CD95.

Failure of mLANA-null virus to reactivate from splenocytes correlates with the absence of viral episomes.

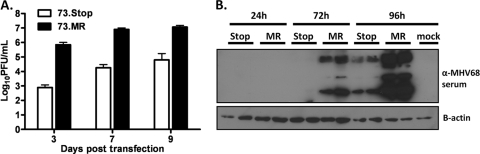

We considered two possibilities that might account for the failure of mLANA-null virus-infected splenocytes to reactivate upon explant. First, we addressed whether the absence of mLANA might impact the initiation of the viral replication cycle in the absence of virion entry and the release of tegument proteins, which would be anticipated to mimic aspects of virus reactivation. Thus, to assess the capacity of mLANA-null virus to initiate de novo virion production from naked viral DNA, we transfected either 73.Stop-BAC or 73.MR-BAC DNA into permissive Vero cells and harvested supernatants at 3, 7, and 9 days posttransfection. To control for transfection efficiency, several replicate experiments were performed, and GFP expression in the transfected Vero cells, arising from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) IE promoter-driven GFP expression cassette present in the BAC, was monitored and shown to be equivalent (data not shown). Titers of tissue culture supernatants harvested from each transfection were determined by a plaque assay on NIH 3T12 fibroblasts. Notably, the 73.Stop-BAC-transfected cells displayed a severe, 3-log replication defect at day 3 posttransfection (Fig. 7 A). Importantly, a replication defect of this magnitude was not observed for fibroblasts infected with mLANA-null virus (30, 52). The observed replication defect was slightly ameliorated by day 9, most likely due to subsequent rounds of infection with progeny virus produced from the transfected cells. To show that this effect happens very early in the transition from DNA to virus production and is not due to a failure to efficiently plaque 73.Stop virus, we transfected Vero cells with 73.Stop-BAC or 73.MR-BAC in duplicate and harvested lysates at 24, 72, and 96 h posttransfection (Fig. 7B). We observed that the LANA-null BAC displayed a significant lag in the expression of lytic antigens, consistent with the observed decrease in viral titers. This finding is in contrast to the overexpression of lytic antigens previously seen under some experimental conditions upon infection of permissive fibroblasts with the 73.Stop virus (27).

FIG. 7.

A functional mLANA gene is required for the efficient replication of MHV68 following transfection of viral DNA in permissive fibroblasts. (A) NIH 3T12 fibroblasts were transfected with 0.5 μg of either 73.Stop-BAC or 73.MR-BAC (MR) DNA. At 3, 7, and 9 days posttransfection, supernatants were harvested, and titers of infectious virus produced were determined. The data are representative of at least three replicate experiments. (B) Vero cells were transfected in duplicate as described above, and lysates were harvested at 24, 72, and 96 h. Western blots for lytic MHV68 antigen and β-actin are shown.

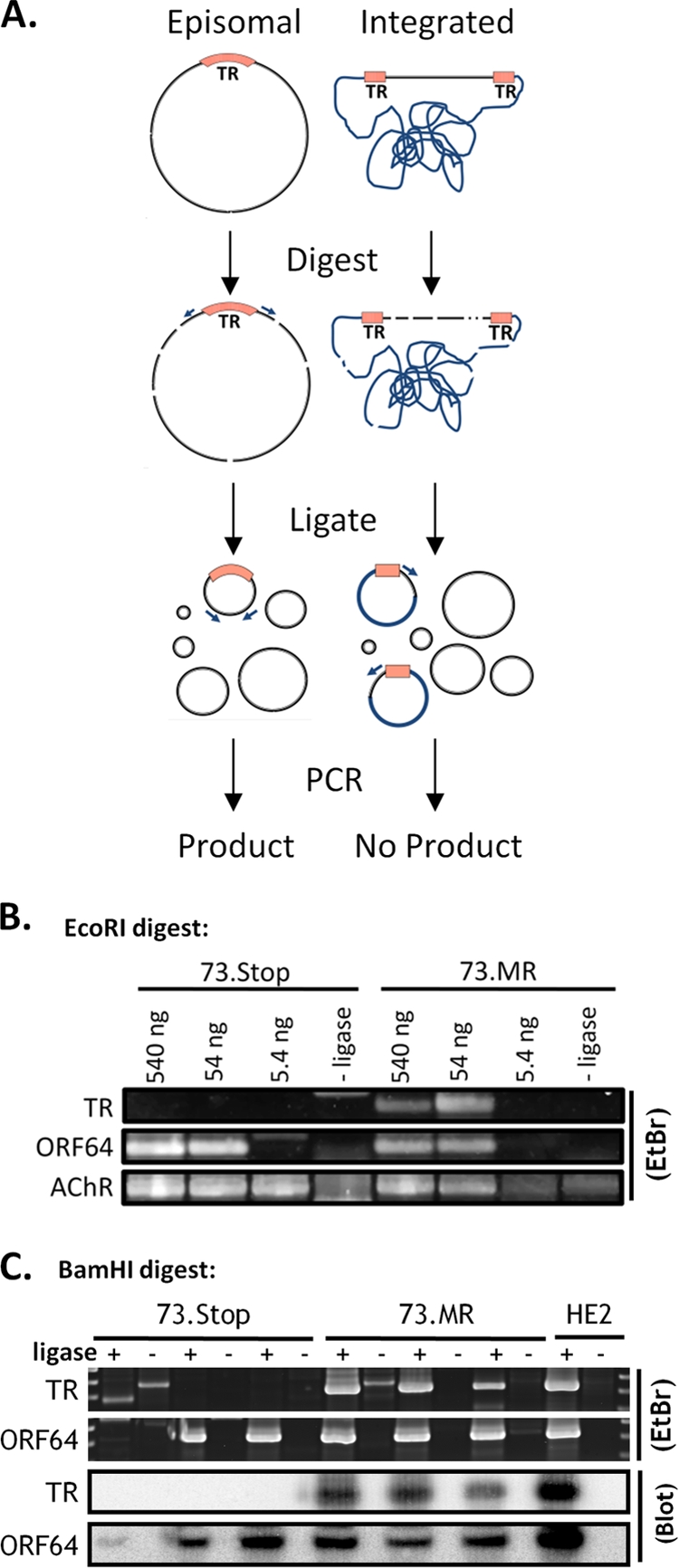

Second, we considered whether, in the absence of mLANA expression, the viral genome might integrate into the host chromosome, as it has been shown that HVS LANA and KSHV LANA are important for facilitating episomal maintenance of the viral genome in rapidly dividing cells (15, 36, 40). Furthermore, it was previously suggested that KSHV terminal repeat (TR)-containing plasmids integrate into the cellular genome under antibiotic selection when LANA is not present (36). Notably, many characterized gammaherpesvirus integration events have shown that the viral genomes preferentially integrate into chromosomes through their terminal repeats (37, 38). In contrast, episomal virus genomes have fused terminal repeats, and the left and right ends of the viral unique sequences are thus physically connected through the fusion of the terminal repeats. To assess the presence of viral episomes, we employed a digestion-and-circularization-mediated PCR (DC-PCR) strategy (12) to detect the presence of fused terminal repeats. Splenocytes from mice infected intraperitoneally with 73.Stop or 73.MR virus were harvested at day 18 postinfection, and total genomic DNA was prepared. The recovered genomic DNA was digested with either EcoRI or BamHI, neither of which cuts within the terminal repeats, followed by the dilution of the digested DNA and ligation under conditions that favor intramolecular ligation (i.e., circle formation) (Fig. 8 A). Nested sets of PCR primers were designed a short distance upstream of the respective enzyme digestion sites, oriented toward the cut site, such that a PCR product could be generated only following the ligation of each end to form a circle (Fig. 8A). One set of primers was designed to detect fused terminal repeats, and another was designed to detect the digested and circularized EcoRI-H or BamHI-A2 fragments, containing ORF64, in the middle of the unique region as a control for the detection of viral DNA following digestion and circularization. We observed in four independent sets of infections with both 73.Stop and 73.MR that we could readily detect the ORF64-containing circles (Fig. 8B and C). However, while we also consistently observed the fused terminal repeat product in splenocytes recovered from 73.MR-infected mice, we never observed the presence of the fused terminal repeat product in 73.Stop-infected splenocytes (Fig. 8B and C). This finding implies that mLANA is needed in vivo at early times of latency to facilitate the maintenance of MHV68 as a circular genome in latently infected splenocytes. However, this does not necessarily demonstrate the integration of the viral genome. Another possibility is that the virus may be present in a linear, extrachromosomal form.

FIG. 8.

Digestion-circularization PCR reveals mLANA-dependent episome formation during early latency in the spleen. (A) Diagram of the DC-PCR method. Primers are designed facing away from each other on opposite sides of the TR. After digestion and intramolecular circular formation and ligation, the primers will produce a product during PCR. If the virus is integrated, i.e., does not have fused terminal repeats, only one primer binding site will be contained in the resulting circles, and no product is formed. (B) EcoRI digestion and circularization. Numbers above the gel represent the amounts of digested DNA that went into each ligation reaction mixture. One set of mice was analyzed for 73.MR and 73.Stop infections. The murine acetyl choline receptor (AChR) was a control for digestion and intramolecular circularization. (C) BamHI digestion and circularization. Sixty nanograms of DNA was placed into each ligation reaction mixture. Each pair of lanes (ligase +/−) represents a separate group of mice. Ligase-negative reactions are used as a negative control. DNA from the latently infected HE2 (28) cell line was used as a positive control. Southern blots of the PCR products using probes that span the ligated junction further confirmed the specificity of the PCR. EtBr, ethidium bromide.

DISCUSSION

In this report we identify a role for the MHV68 LANA homolog in virus reactivation from splenocytes and PECs as well as provide initial evidence that mLANA plays a critical role in establishing and/or maintaining the viral genome as an episome in vivo. A striking finding here is the capacity of the mLANA-null virus to establish latency in the spleen following the intraperitoneal inoculation of C57BL/6 mice, in contrast to data from previous studies that demonstrated a complete failure to establish latency following intranasal inoculation (30, 52). As discussed above, we previously observed a significant acute replication defect with the mLANA-null virus in the lungs following intranasal inoculation (52). However, a substantial increase of the inoculating dose of the virus, which greatly increased the peak titers of the virus in the lungs, did not overcome the defect in the establishment of latency (52). This finding suggested a more complex relationship between the route of administration and establishment of latency in the spleen in immunocompetent mice. This complexity is underscored by the previously reported observation that the establishment of latency in the spleen following intranasal inoculation is severely impaired in B-cell-deficient mice (MuMT) but that splenic latency is robustly established in these mice following intraperitoneal inoculation (72, 78). Similarly, M2-null mutants also exhibit a more severe establishment-of-latency phenotype in the spleen following intranasal inoculation than following intraperitoneal inoculation (39, 43), and M2-null mutants also exhibit a profound defect in reactivation from B cells (39, 48). Taken together, these data suggest that latently infected B cells that traffic to the spleen and reactivate play a pivotal role in the initial establishment of latency following intranasal inoculation but not following intraperitoneal inoculation (64). Thus, the inability of mLANA-null virus to reactivate from splenocytes may be linked directly to the failure of this mutant virus to establish latency following the intranasal inoculation of immunocompetent mice.

LANA was originally identified in a KSHV latently infected tumor cell line using serum from patients with Kaposi's sarcoma (31). Subsequent studies demonstrated that LANA expression could be detected in every KS-associated tumor and proliferative disease (11, 31, 56, 59, 67, 75). Those studies and others established a correlation between LANA and KSHV disease, a notion further bolstered by studies that identified numerous functions of LANA, many of which appeared to be consistent with its putative role as a viral oncogene. Functions attributed to LANA proteins include regulating the transcription of cell cycle genes (32), blunting cellular responses to virus infection and DNA damage (27), interacting with p53 and other tumor suppressors (45, 75), and preventing its own presentation by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on infected cells (46). LANA expression is associated with these tumor-like phenotypes, and thus, much of what is known about LANA in the context of KSHV infection has been worked out with cancer cells. However, there is no basis for assuming that the constitutive expression of LANA is normal during chronic rhadinovirus infections. Like other herpesvirus latency-associated genes, including EBNA-1, another well-studied gammaherpesvirus protein suggested to promote episome maintenance (63, 83), its expression is likely tightly controlled.

As discussed above, episomal maintenance is perhaps the most well-known function attributed to LANA homologs. Similar to what has been shown for EBNA-1 of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (82, 83), it has been suggested by studies with both HVS LANA and KSHV LANA that LANA (i) maintains viral genomes or minigenomes as extrachromosomal episomes and (ii) physically associates, or tethers, the viral genome to host DNA to ensure the faithful partitioning of the viral genome into daughter cells (5, 15, 16, 76). We speculated that in the absence of LANA, the virus would integrate into host cells and/or eventually be lost with host cell division. Consistent with episome maintenance assays performed for HVS and KSHV LANA, we were unable to detect episomes with fused terminal repeats in vivo at day 18 in the absence of mLANA. At this time point, a large percentage of MHV68-positive cells exhibited a germinal center phenotype and were actively proliferating (14, 53). Thus, this may be the point at which in vitro maintenance assay data may most strongly correlate with virus infection of B cells in vivo, and in the absence of mLANA, the integrated viruses are the ones that survive the rapid cell division in the germinal center. Notably, it is the germinal center subset of B cells that have the most robust expression of orf73 transcripts (50). Furthermore, germinal center B cells that survive become either memory cells or plasma cells; memory B cells are the long-lived latency reservoir (26, 81), and plasma cells are a major cell type reactivating virus (48). It is possible that mLANA thus plays a central role in retaining the virus in a state (i.e., viral episome) that can rapidly switch from latency to reactivation.

Our data demonstrate that gammaherpesvirus infection can persist in vivo in the absence of an episomal form, either maintained as a linear piece of DNA or integrated into the host chromosome. There is precedent both for MHV68 being carried as linear DNA upon the infection of primary lymphocytes (24) and for gammaherpesvirus integration (18, 20, 42). Both possibilities may lead to a block in virus reactivation from splenocytes (which largely reflect the infection of B cells), likely due to the absence of a mechanism for the circularization or for the excision of the viral DNA from the host chromosome. Notably, 73.Stop virus can reactivate, albeit at a greatly reduced efficiency, from infected peritoneal cells and perhaps from an undetectable population of splenocytes. This minor reactivation may reflect reactivation from a population of infected macrophages that do not require mLANA to maintain the capacity of the virus to reactivate due to either the lack of the active proliferation of those cells or another cell type-specific factor. Similarly, when permissive cells are transfected with MHV68 BAC DNA, 73.STOP-BAC lags behind 73.MR-BAC in both lytic antigen production and virion production, indicating a secondary role for mLANA early in the transition from latency to reactivation.

These data may confound the working definition of latency commonly used in the herpesvirus field. It is generally accepted that a latent virus is one that “may be induced to multiply and that does not exist in an infectious form” (62). Furthermore, episomal herpesvirus genomes are associated with latently infected cells (49, 62). However, a definitive molecular definition of latency is still lacking in the gammaherpesvirus field, and although we know that there is little viral gene expression during latency, there are distinct programs of a limited number of tightly regulated genes observable in EBV-transformed cells and in disease (61, 68). It stands to reason that the transcription of viral genes must be an important aspect of the establishment and maintenance of latency, giving some advantage to virus-infected cells to survive and become a long-term reservoir for the virus. With the mLANA-null virus, we observed the presence of the viral genome in the absence of infectious virus, but the viral genome does not appear to be episomal. We did, however, observe similar patterns of viral gene expression in mutant and wild-type virus-infected cells as well as the long-term carriage of the viral genome in vivo. Thus, the mLANA-null virus is indeed present within the host indefinitely, in the preferred cell type, and at levels equivalent to those of the wild-type virus. In addition, because the mLANA-null virus-infected cells are capable of expressing viral genes, the mutant virus presumably retains the capacity to alter the cell, even though it is incapable of efficiently reentering the lytic cycle to produce progeny virions. Thus, the ability of the mLANA-null virus to ultimately access the same cellular reservoirs that are latently infected with wild-type MHV68 argues in support of a broader definition of latency.

This idea of a more complex definition of latency has been building for several years with both KSHV and EBV tissue culture models. KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cells have been treated with lentiviruses that knock down LANA, and while the genome copy number is reduced, latency persists (34). Furthermore, for both EBV (55) and KSHV (74), it was shown that viral replication origins exist and function outside the EBNA-1-dependent OriP and proposed LANA-dependent terminal repeat (TR) origin, respectively. In the same regard, it is also now appreciated that LANA itself is not sufficient to maintain a TR-containing plasmid, suggesting that specific cellular mechanisms are required for this function (35). Finally, a study using an EBV mutant lacking EBNA-1 showed that this virus not only can latently infect B cells but also can drive B-cell immortalization albeit with a significantly reduced efficiency (likely due to the need for the virus to integrate into the host genome) (41). The data presented in the present study argue that what we observed in vivo with the 73.Stop virus is a form of latency in the absence of both viral episomes and the latency maintenance protein mLANA, because (i) we observed a similar pattern of latency gene expression, (ii) the frequency of viral genome-positive cells persists and is equivalent long-term with the wild-type virus, and (iii) B cells are predominantly infected with 73.Stop, similar to the wild type.

With respect to the persistence of herpesviruses in the absence of episome formation, it was previously shown that human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), a betaherpesvirus, integrates into host chromosomes as a normal part of its life cycle (17). Furthermore, HHV-6 is apparently able to reactivate from this integrated state, as the virus is frequently detected in the saliva of healthy people and in the blood of bone marrow transplant patients (10, 47). Integrated HHV-6 was also observed in vertical transmission from parent to child, arguing for integration as an efficient mechanism of survival (2). Additionally, the alphaherpesvirus Marek's disease virus (MDV), which is highly pathogenic in chickens, is found integrated exclusively into host chromosomes but also retains the capacity to be excised and replicate (19, 21). Notably, with respect to gammaherpesvirus biology, the integration of the viral genome at the terminal repeats would prevent the expression of viral genes encoded across the fused terminal repeats (e.g., EBV LMP2a and KSHV K15) (8). The consequences of the loss of such gene products on either the establishment or maintenance of viral latency in vivo are currently unknown. In the case of LMP2a, it was hypothesized previously that it plays a critical role in the survival of EBV-infected germinal center B cells (9) and, thus, likely plays a critical role in the generation of those virus-infected memory B cells that arise from the virus-driven differentiation of infected naïve B cells (3, 9). At present, no such viral gene product encoded across the fused terminal repeats of MHV68 has been identified.

In summary, the results presented here reveal a crucial role for mLANA in reactivation and provide in vivo support for the notion that an episome is a prerequisite for virus reactivation but not the long-term carriage of MHV68. The data also show that mLANA is important early in infection both in mounting an aggressive lytic infection at the site of inoculation and in establishing episomal latency. Our data further demonstrate the resilience of herpesvirus latency: the virus can continue to persist in the host even in the absence of the proposed latency maintenance protein.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH research grants R01 CA52004 and R01 CA095318. S.H.S. was also supported by NIH research grants R01 CA058524, R01 CA087650, R01 AI58057, and R01 AI073830.

We thank members of the Speck laboratory for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, R. D., II, S. Dickerson, and S. H. Speck. 2006. Identification of spliced gammaherpesvirus 68 LANA and v-cyclin transcripts and analysis of their expression in vivo during latent infection. J. Virol. 80:2055-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbuckle, J. H., M. M. Medveczky, J. Luka, S. H. Hadley, A. Luegmayr, D. Ablashi, T. C. Lund, J. Tolar, K. De Meirleir, J. G. Montoya, A. L. Komaroff, P. F. Ambros, and P. G. Medveczky. 2010. The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:5563-5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babcock, G. J., and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. Tonsillar memory B cells, latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus, express the restricted pattern of latent genes previously found only in Epstein-Barr virus-associated tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:12250-12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballestas, M. E., P. A. Chatis, and K. M. Kaye. 1999. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science 284:641-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballestas, M. E., and K. M. Kaye. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mediates episome persistence through cis-acting terminal repeat (TR) sequence and specifically binds TR DNA. J. Virol. 75:3250-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbera, A. J., J. V. Chodaparambil, B. Kelley-Clarke, V. Joukov, J. C. Walter, K. Luger, and K. M. Kaye. 2006. The nucleosomal surface as a docking station for Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus LANA. Science 311:856-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton, E. S., M. L. Lutzke, R. Rochford, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2005. Alpha/beta interferons regulate murine gammaherpesvirus latent gene expression and reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 79:14149-14160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernasconi, M., C. Berger, J. A. Sigrist, A. Bonanomi, J. Sobek, F. K. Niggli, and D. Nadal. 2006. Quantitative profiling of housekeeping and Epstein-Barr virus gene transcription in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines using an oligonucleotide microarray. Virol. J. 3:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldwell, R. G., J. B. Wilson, S. J. Anderson, and R. Longnecker. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A drives B cell development and survival in the absence of normal B cell receptor signals. Immunity 9:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrigan, D. R., and K. K. Knox. 1994. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) isolation from bone marrow: HHV-6-associated bone marrow suppression in bone marrow transplant patients. Blood 84:3307-3310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cesarman, E., P. S. Moore, P. H. Rao, G. Inghirami, D. M. Knowles, and Y. Chang. 1995. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood 86:2708-2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu, C. C., W. E. Paul, and E. E. Max. 1992. Quantitation of immunoglobulin mu-gamma 1 heavy chain switch region recombination by a digestion-circularization polymerase chain reaction method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:6978-6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman, H. M., S. Efstathiou, and P. G. Stevenson. 2005. Transcription of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 ORF73 from promoters in the viral terminal repeats. J. Gen. Virol. 86:561-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins, C. M., J. M. Boss, and S. H. Speck. 2009. Identification of infected B-cell populations by using a recombinant murine gammaherpesvirus 68 expressing a fluorescent protein. J. Virol. 83:6484-6493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins, C. M., M. M. Medveczky, T. Lund, and P. G. Medveczky. 2002. The terminal repeats and latency-associated nuclear antigen of herpesvirus saimiri are essential for episomal persistence of the viral genome. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2269-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotter, M. A., II, and E. S. Robertson. 1999. The latency-associated nuclear antigen tethers the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome to host chromosomes in body cavity-based lymphoma cells. Virology 264:254-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daibata, M., T. Taguchi, Y. Nemoto, H. Taguchi, and I. Miyoshi. 1999. Inheritance of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 DNA. Blood 94:1545-1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delecluse, H. J., S. Bartnizke, W. Hammerschmidt, J. Bullerdiek, and G. W. Bornkamm. 1993. Episomal and integrated copies of Epstein-Barr virus coexist in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. J. Virol. 67:1292-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delecluse, H. J., and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. Status of Marek's disease virus in established lymphoma cell lines: herpesvirus integration is common. J. Virol. 67:82-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delecluse, H. J., S. Kohls, J. Bullerdiek, and G. W. Bornkamm. 1992. Integration of EBV in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 182:367-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delecluse, H. J., S. Schuller, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. Latent Marek's disease virus can be activated from its chromosomally integrated state in herpesvirus-transformed lymphoma cells. EMBO J. 12:3277-3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeZalia, M., and S. H. Speck. 2008. Identification of closely spaced but distinct transcription initiation sites for the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 latency-associated M2 gene. J. Virol. 82:7411-7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dittmer, D., M. Lagunoff, R. Renne, K. Staskus, A. Haase, and D. Ganem. 1998. A cluster of latently expressed genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 72:8309-8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutia, B. M., J. P. Stewart, R. A. Clayton, H. Dyson, and A. A. Nash. 1999. Kinetic and phenotypic changes in murine lymphocytes infected with murine gammaherpesvirus-68 in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 80(Pt. 10):2729-2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fickenscher, H., and B. Fleckenstein. 2001. Herpesvirus saimiri. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356:545-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flano, E., I. J. Kim, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2002. Gamma-herpesvirus latency is preferentially maintained in splenic germinal center and memory B cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:1363-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forrest, J. C., C. R. Paden, R. D. Allen III, J. Collins, and S. H. Speck. 2007. ORF73-null murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reveals roles for mLANA and p53 in virus replication. J. Virol. 81:11957-11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest, J. C., and S. H. Speck. 2008. Establishment of B-cell lines latently infected with reactivation-competent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 provides evidence for viral alteration of a DNA damage-signaling cascade. J. Virol. 82:7688-7699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Fowler, P., and S. Efstathiou. 2004. Vaccine potential of a murine gammaherpesvirus-68 mutant deficient for ORF73. J. Gen. Virol. 85:609-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowler, P., S. Marques, J. P. Simas, and S. Efstathiou. 2003. ORF73 of murine herpesvirus-68 is critical for the establishment and maintenance of latency. J. Gen. Virol. 84:3405-3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao, S. J., L. Kingsley, D. R. Hoover, T. J. Spira, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, P. Parry, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garber, A. C., M. A. Shu, J. Hu, and R. Renne. 2001. DNA binding and modulation of gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 75:7882-7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gargano, L. M., J. C. Forrest, and S. H. Speck. 2009. Signaling through Toll-like receptors induces murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivation in vivo. J. Virol. 83:1474-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godfrey, A., J. Anderson, A. Papanastasiou, Y. Takeuchi, and C. Boshoff. 2005. Inhibiting primary effusion lymphoma by lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA. Blood 105:2510-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grundhoff, A., and D. Ganem. 2004. Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 113:124-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grundhoff, A., and D. Ganem. 2003. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus permits replication of terminal repeat-containing plasmids. J. Virol. 77:2779-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulley, M. L., M. Raphael, C. T. Lutz, D. W. Ross, and N. Raab-Traub. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus integration in human lymphomas and lymphoid cell lines. Cancer 70:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henderson, A., S. Ripley, M. Heller, and E. Kieff. 1983. Chromosome site for Epstein-Barr virus DNA in a Burkitt tumor cell line and in lymphocytes growth-transformed in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:1987-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herskowitz, J., M. A. Jacoby, and S. H. Speck. 2005. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 M2 gene is required for efficient reactivation from latently infected B cells. J. Virol. 79:2261-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu, J., A. C. Garber, and R. Renne. 2002. The latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus supports latent DNA replication in dividing cells. J. Virol. 76:11677-11687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humme, S., G. Reisbach, R. Feederle, H. J. Delecluse, K. Bousset, W. Hammerschmidt, and A. Schepers. 2003. The EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) enhances B cell immortalization several thousandfold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:10989-10994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurley, E. A., S. Agger, J. A. McNeil, J. B. Lawrence, A. Calendar, G. Lenoir, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1991. When Epstein-Barr virus persistently infects B-cell lines, it frequently integrates. J. Virol. 65:1245-1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacoby, M. A., H. W. Virgin IV, and S. H. Speck. 2002. Disruption of the M2 gene of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 alters splenic latency following intranasal, but not intraperitoneal, inoculation. J. Virol. 76:1790-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeong, J., J. Papin, and D. Dittmer. 2001. Differential regulation of the overlapping Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGCR (orf74) and LANA (orf73) promoters. J. Virol. 75:1798-1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul, R., S. C. Verma, and E. S. Robertson. 2007. Protein complexes associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded LANA. Virology 364:317-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwun, H. J., S. R. da Silva, I. M. Shah, N. Blake, P. S. Moore, and Y. Chang. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 mimics Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 immune evasion through central repeat domain effects on protein processing. J. Virol. 81:8225-8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy, J. A., F. Ferro, D. Greenspan, and E. T. Lennette. 1990. Frequent isolation of HHV-6 from saliva and high seroprevalence of the virus in the population. Lancet 335:1047-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang, X., C. M. Collins, J. B. Mendel, N. N. Iwakoshi, and S. H. Speck. 2009. Gammaherpesvirus-driven plasma cell differentiation regulates virus reactivation from latently infected B lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindahl, T., A. Adams, G. Bjursell, G. W. Bornkamm, C. Kaschka-Dierich, and U. Jehn. 1976. Covalently closed circular duplex DNA of Epstein-Barr virus in a human lymphoid cell line. J. Mol. Biol. 102:511-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marques, S., S. Efstathiou, K. G. Smith, M. Haury, and J. P. Simas. 2003. Selective gene expression of latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 in B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 77:7308-7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez-Guzman, D., T. Rickabaugh, T. T. Wu, H. Brown, S. Cole, M. J. Song, L. Tong, and R. Sun. 2003. Transcription program of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 77:10488-10503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moorman, N. J., D. O. Willer, and S. H. Speck. 2003. The gammaherpesvirus 68 latency-associated nuclear antigen homolog is critical for the establishment of splenic latency. J. Virol. 77:10295-10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moser, J. M., J. W. Upton, R. D. Allen III, C. B. Wilson, and S. H. Speck. 2005. Role of B-cell proliferation in the establishment of gammaherpesvirus latency. J. Virol. 79:9480-9491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nash, A. A., B. M. Dutia, J. P. Stewart, and A. J. Davison. 2001. Natural history of murine gamma-herpesvirus infection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356:569-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norio, P., and C. L. Schildkraut. 2004. Plasticity of DNA replication initiation in Epstein-Barr virus episomes. PLoS Biol. 2:e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parravicini, C., B. Chandran, M. Corbellino, E. Berti, M. Paulli, P. S. Moore, and Y. Chang. 2000. Differential viral protein expression in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected diseases: Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 156:743-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rainbow, L., G. M. Platt, G. R. Simpson, R. Sarid, S. J. Gao, H. Stoiber, C. S. Herrington, P. S. Moore, and T. F. Schulz. 1997. The 222- to 234-kilodalton latent nuclear protein (LNA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) is encoded by orf73 and is a component of the latency-associated nuclear antigen. J. Virol. 71:5915-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Renne, R., C. Barry, D. Dittmer, N. Compitello, P. O. Brown, and D. Ganem. 2001. Modulation of cellular and viral gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 75:458-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rettig, M. B., H. J. Ma, R. A. Vescio, M. Pold, G. Schiller, D. Belson, A. Savage, C. Nishikubo, C. Wu, J. Fraser, J. W. Said, and J. R. Berenson. 1997. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of bone marrow dendritic cells from multiple myeloma patients. Science 276:1851-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rochford, R., M. L. Lutzke, R. S. Alfinito, A. Clavo, and R. D. Cardin. 2001. Kinetics of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 gene expression following infection of murine cells in culture and in mice. J. Virol. 75:4955-4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rogers, R. P., J. L. Strominger, and S. H. Speck. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus in B lymphocytes: viral gene expression and function in latency. Adv. Cancer Res. 58:1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roizman, B., and A. E. Sears. 1987. An inquiry into the mechanisms of herpes simplex virus latency. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41:543-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schaefer, B. C., M. Woisetschlaeger, J. L. Strominger, and S. H. Speck. 1991. Exclusive expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 in Burkitt lymphoma arises from a third promoter, distinct from the promoters used in latently infected lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:6550-6554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siegel, A. M., U. S. Rangaswamy, R. J. Napier, and S. H. Speck. 2010. Blimp-1-dependent plasma cell differentiation is required for efficient maintenance of murine gammaherpesvirus latency and antiviral antibody responses. J. Virol. 84:674-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simas, J. P., and S. Efstathiou. 1998. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68: a model for the study of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 6:276-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simas, J. P., D. Swann, R. Bowden, and S. Efstathiou. 1999. Analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus-68 transcription during lytic and latent infection. J. Gen. Virol. 80(Pt. 1):75-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soulier, J., L. Grollet, E. Oksenhendler, J. M. Miclea, P. Cacoub, A. Baruchel, P. Brice, J. P. Clauvel, M. F. d'Agay, M. Raphael, et al. 1995. Molecular analysis of clonality in Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1131-1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Speck, S. H. 2002. EBV framed in Burkitt lymphoma. Nat. Med. 8:1086-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Speck, S. H., and H. W. Virgin. 1999. Host and viral genetics of chronic infection: a mouse model of gamma-herpesvirus pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun, R., S. F. Lin, K. Staskus, L. Gradoville, E. Grogan, A. Haase, and G. Miller. 1999. Kinetics of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J. Virol. 73:2232-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tibbetts, S. A., J. Loh, V. Van Berkel, J. S. McClellan, M. A. Jacoby, S. B. Kapadia, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2003. Establishment and maintenance of gammaherpesvirus latency are independent of infective dose and route of infection. J. Virol. 77:7696-7701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Usherwood, E. J., J. P. Stewart, K. Robertson, D. J. Allen, and A. A. Nash. 1996. Absence of splenic latency in murine gammaherpesvirus 68-infected B cell-deficient mice. J. Gen. Virol. 77(Pt. 11):2819-2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verma, S. C., T. Choudhuri, R. Kaul, and E. S. Robertson. 2006. Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interacts with origin recognition complexes at the LANA binding sequence within the terminal repeats. J. Virol. 80:2243-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verma, S. C., K. Lan, T. Choudhuri, M. A. Cotter, and E. S. Robertson. 2007. An autonomous replicating element within the KSHV genome. Cell Host Microbe 2:106-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Verma, S. C., K. Lan, and E. Robertson. 2007. Structure and function of latency-associated nuclear antigen. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 312:101-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Verma, S. C., and E. S. Robertson. 2003. ORF73 of herpesvirus saimiri strain C488 tethers the viral genome to metaphase chromosomes and binds to cis-acting DNA sequences in the terminal repeats. J. Virol. 77:12494-12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Virgin, H. W., IV, R. M. Presti, X. Y. Li, C. Liu, and S. H. Speck. 1999. Three distinct regions of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 genome are transcriptionally active in latently infected mice. J. Virol. 73:2321-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weck, K. E., M. L. Barkon, L. I. Yoo, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin IV. 1996. Mature B cells are required for acute splenic infection, but not for establishment of latency, by murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 70:6775-6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weck, K. E., A. J. Dal Canto, J. D. Gould, A. K. O'Guin, K. A. Roth, J. E. Saffitz, S. H. Speck, and H. W. Virgin. 1997. Murine gamma-herpesvirus 68 causes severe large-vessel arteritis in mice lacking interferon-gamma responsiveness: a new model for virus-induced vascular disease. Nat. Med. 3:1346-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weck, K. E., S. S. Kim, H. W. Virgin IV, and S. H. Speck. 1999. B cells regulate murine gammaherpesvirus 68 latency. J. Virol. 73:4651-4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Willer, D. O., and S. H. Speck. 2003. Long-term latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection is preferentially found within the surface immunoglobulin D-negative subset of splenic B cells in vivo. J. Virol. 77:8310-8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yates, J., N. Warren, D. Reisman, and B. Sugden. 1984. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:3806-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yates, J. L., N. Warren, and B. Sugden. 1985. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 313:812-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]