Abstract

Understanding the mechanisms by which specific microRNAs regulate cell migration and invasion is a timely and significant problem in cancer cell biology. miR-10b is of interest in this regard because its expression is altered in breast and other cancers. Our analysis of potential miR-10b targets identified Tiam1 (T lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1), a guanidine exchange factor for Rac. We demonstrate, using an miR-10b synthetic precursor, expression vector, and antisense oligonucleotide, that miR-10b represses Tiam1 expression in breast carcinoma cells and that it interacts with the 3′-UTR of Tiam1. Consistent with the involvement of Tiam1 in cell motility, we observed that miR-10b suppresses the ability of breast carcinoma cells to migrate and invade. Importantly, we demonstrate that miR-10b also inhibits Tiam1-mediated Rac activation. These data provide a mechanism for the regulation of Tiam1-mediated Rac activation in breast cancer cells and need to be considered in the context of other reported functions for miR-10b.

Keywords: Cell Migration, MicroRNA, Rho, Tumor, Tumor Metastases, Rac, Tiam1

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)2 are a class of small noncoding RNAs that control gene expression by targeting mRNAs and triggering either translational repression or mRNA degradation (1). Convincing evidence exists that miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in human cancer (2–5) and that they can affect key cell biological processes that affect tumor progression including migration, invasion, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (6, 7), and metastasis (8–10). The challenge ahead is to elucidate specific mechanisms by which miRNAs regulate such processes.

miR-10b expression has been reported to be significantly deregulated in breast cancer (3), and recent studies indicate that it can promote the metastasis of breast carcinoma cells (11). Given the potential importance of miR-10b in breast and other cancers, a key issue is the identification of miR-10b targets that execute its biological functions. HoxD10 has been identified as a miR-10b target, a finding that is significant because HoxD10 represses expression of the prometastatic gene RHOC (11). Most likely, however, miR-10b targets additional genes that affect the behavior of breast carcinoma cells. In the current study, we sought to identify such novel targets of miR-10b and to assess their regulation by miR-10b in the context of breast cancer cell biology.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines

The SUM159PT and SUM149PT cell lines were obtained from Dr. Steve Ethier (University of Michigan). T-47D and MDA-MB-435 cells were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD).

RNA Isolation and miRNA Detection

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) detection of the mature form of miRNAs was performed using TaqMan miRNA reverse transcription kit and TaqMan human microarray assays for miR-10b and the miR-10b mutant (Ambion). U6 small nuclear RNA was used as an internal control.

Oligonucleotide Transfection

Pre-miR miRNA precursor molecules (Dharmacon) are synthetic miRNA mimics designed for functional analyses and target site validation. Cells were transfected with 20 nm pre-miR hsa-miR-10b precursor, a custom-designed miR-10b seed mutant precursor with a single base pair substitution in the seed region of the mature strand, or a pre-miR miRNA precursor nontargeting negative control at 50% confluence using DharmaFECT 4 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). 72 h after transfection, cells were plated for migration and invasion assays or harvested for Rac activity assays. A custom-designed 2′-O-methyl antisense oligonucleotide (Dharmacon) to mature miR-10b was used for loss-of-function analyses along with a control antisense oligonucleotide that targets luciferase (Dharmacon). T-47D and MDA-MB-435 cells were transfected with 20 nm antisense oligonucleotide as above. Nontargeting siRNA or siRNAs designed to target Tiam1 were SMARTPools from Dharmacon and cells were transfected with 20 nm each pool. For Tiam1 rescue experiments, cells were transfected with 20 nm miRNA precursor and 0.6 pmol of a human Tiam1 full-length construct (Kathleen O'Connor, University of Kentucky) using DharmaFECT Duo transfection reagent (Dharmacon).

Migration and Invasion Assays

For migration assays, both the upper and lower surfaces of transwell chambers (8-μm pore, Costar) were coated overnight with collagen (15 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. For invasion assays, the upper surface of the transwells was coated overnight with 0.5 μg Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Cells were harvested at 80% confluence by trypsinization and resuspended in HamsF12 or RPMI 1640 containing 0.25% heat-inactivated fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin. The coated surfaces of the transwells were blocked with media containing bovine serum albumin for 30–60 min at 37 °C. Cells (2 × 104 in a total volume of 100 μl) were loaded into the upper chamber and NIH-3T3 conditioned media was added to the lower chamber. Assays proceeded for 4 h for SUM159PT cells, 6 h for MDA-MB-435 cells, and 24 h for SUM149PT and T-47D cells at 37 °C. At the completion of the assays, the upper chamber was swabbed to remove residual cells and fixed with methanol. Cells on the lower surface of the membrane were mounted in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole mounting media (Vector Laboratories), and the number of cells was determined for five independent fields in triplicate with a 10× objective and fluorescence.

Constructs

The MDH1-PGK-GFP-premiR-10b and MDH1-PGK-GFP vectors were obtained from Addgene (11). 293T cells were transfected at 50% confluence by a Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) complex containing a ratio of envelope plasmid (1.75 μg), packaging plasmid (3.25 μg), and MDH1-PGK-GFP-2.0 vector expressing pre-miR-10b or no insert in Optimem (Invitrogen). Virus was harvested 2 days following transfection and clarified, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter to be used immediately or stored at −80 °C. Recipient SUM159PT and SUM149PT cells were plated to reach 50% confluence after 24 h, and virus was added to cells at a ratio of virus:fresh media containing polybrene (8 μg/ml) of 1:1. For luciferase assays, a 60-bp region of the Tiam1 3′-UTR containing the binding site for miR-10b was cloned into the pMIR-REPORT luciferase construct (Ambion). A second insert containing a single base pair mutation in the seed-binding site, comparable to the miR-10b mutant, was cloned into the same construct to generate a luciferase construct with a mutated miR-10b-binding site for control.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared by lysis in ice-cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. Lysates (50 μg) were separated by electrophoresis through 8 or 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20, blotted with the antibodies for Tiam1 (1:800, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), actin and tubulin (1:5000, Sigma), or Rac1 (1:1000, Transduction Laboratories) overnight, followed by secondary peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies, and detection was by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Cells in 24-well plates at 50% confluence were co-transfected with firefly luciferase reporter gene construct (200–0.5 μg) and 1–0.5 μg of Renilla luciferase construct (for normalization) using DharmaFECT Duo (Dharmacon). Cell extracts were prepared 24–48 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega).

Rac Activity Assays

Rac activity assays were based on established protocols (12, 13). The bacterially produced Rac/cdc42 binding domain of Pak (PBD)-GST fusion protein was extracted and used to coat glutathione Sepharose (GST) beads. Serum-starved cells were harvested by addition of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin). Extracts were cleared by centrifugation, and 10% of the total was removed. GST-PBD-coupled beads were added to the remaining extracts with 2 volumes of binding buffer (25 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mm dithiothreitol, 40 mm NaCl, 30 mm MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) for 30 min on a rotating platform at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times in binding buffer and eluted in 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Aliquots of both total cell extracts and the eluents from the PBD beads were immunoblotted for Rac1.

For experiments designed to test the contribution of Rac and cdc42 to miR-10b-regulated migration, MDA-MB-435 cells were transfected with control antisense or miR-10b antisense oligonucleotides as described above. After 24 h, these cells were transfected with N17Rac and N17Cdc42 constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 as described previously (14). Expression of these constructs at equivalent levels was verified by GST immunoblotting. Migration assays were performed 48 h post-transfection of the Rac and cdc42 constructs. In some experiments, cells were transfected with these constructs alone and assayed for migration.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. The Student's t test was used to assess the significance of independent experiments. The criterion p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Initially, we used computational algorithms to identify potential miR-10b target genes. The search program TargetScan revealed several predicted targets of interest in the context of cancer cell biology, including Tiam1 (T lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1) targetscan/miR10. Tiam1 was of particular interest because it is a member of the Dbl family of guanidine exchange factors (GEFs) and its acts as a GEF for the Rho GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42 (15). Its expression correlates with epithelial tumorigenicity, the metastatic potential of human breast cancer cell lines (16), and increased breast cancer grade (17). The predicted target site for miR-10b is a single 8-mer site, comprised of the seed match flanked by both the match at position 8 and the A at position 1 (18).

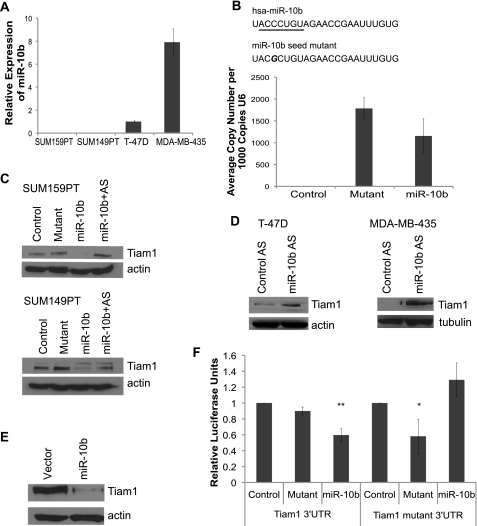

To assess the ability of miR-10b to regulate Tiam1 expression, we used a miR-10b precursor for de novo expression in breast carcinoma cell lines that either lack (SUM149PT and SUM159PT) or express (T-47D and MDA-MB-435) miR-10b (Fig. 1A). This precursor is a chemically modified, double-stranded RNA modeled on the sequence of mature miR-10b. For a control, we designed a miR-10b mutant with a single base pair substitution in the seed sequence of the mature strand (Fig. 1B). By introducing mismatch into the critical seed region, binding of the miRNA to its target genes should be reduced or abolished. A nontargeting miRNA was used as an additional negative control. To examine whether the miR-10b mutant was being expressed at the same level as miR-10b, we conducted qPCR to amplify miR-10b and the miR-10b mutant using sequence specific primers and found that the miR-10b mutant was expressed 1.5-fold higher than miR-10b (Fig. 1B), allaying concerns that the miR-10b mutant was expressed at lower levels than miR-10b.

FIGURE 1.

miR-10b suppresses Tiam1. A, analysis of miR-10b mRNA expression in four different human breast cancer cell lines using qPCR. B, schematic above the bar graph shows the sequences of mature miR-10b and miR-10b seed mutant. The seed sequence of mature miR-10b is underlined. SUM-159PT cells were transfected with nontargeting control miRNA, miR-10b mutant, or miR-10b precursor, and miR expression was quantified by qPCR. The bar graph displays expression of the mature and mutant miR-10b precursors. C, immunoblot of Tiam1 expression in SUM159PT and SUM149PT transfected with non-targeting control miRNA, miR-10b mutant, miR-10b precursor, or co-transfected with miR-10b precursor plus antisense miR-10b. D, immunoblot of Tiam1 expression in T-47D and MDA-MB-435 cells transfected either with control or antisense miR-10b oligonucleotides. E, Tiam1 immunoblot of SUM-159PT cells infected with either miR-10b-expressing or empty vector retrovirus. F, luciferase activity of a Tiam1 3′-UTR or Tiam1 mutant 3′-UTR reporter gene in SUM-159PT cells transfected with either miR-10b, miR-10b mutant, or nontargeting control miRNA. *, p < 0.02. **, p < 0.004. Data represent means ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

We observed a dramatic reduction in Tiam1 expression in both SUM159PT and SUM149PT cells expressing miR-10b, as compared with controls (Fig. 1C). Co-transfection of the miR-10b precursor with a miR-10b antisense oligonucleotide rescued expression of Tiam1. We next asked whether inhibition of endogenous miR-10b in breast carcinoma cells that express this miR would affect Tiam1 expression. Indeed, expression of a miR-10b antisense oligonucleotide increased Tiam1 expression significantly in both cell lines compared with a control oligonucleotide (Fig. 1D). We also used a miR-10b expression vector to confirm that miR-10b inhibits Tiam1 expression and that we were not observing an artifact of the miRNA precursor. This retroviral vector encodes the genomic sequence of the human miR-10b gene in the 3′-UTR of GFP and requires that mature miR-10b be generated through endogenous cellular processing. Ectopic expression of this miR-10b in SUM159PT cells resulted in a significant decrease in Tiam1 expression (Fig. 1E).

To determine whether regulation of Tiam1 expression by miR-10b is direct, we utilized a luciferase reporter gene fused to a sequence of the 3′-UTR of Tiam1 that contains the predicted miR-10b-binding site. Expression of miR-10b reduced the activity of luciferase, whereas a miR-10b seed mutant had no effect, indicating that miR-10b targets Tiam1 directly (Fig. 1F). As a control, we developed a second luciferase reporter with a single base pair mutation in the predicted miR-10b-binding site, at the site corresponding to the miR-10b seed mutant. As expected, miR-10b had no effect on the luciferase activity of this reporter, whereas the miR-10b seed mutant, a perfect match in the seed region, repressed the luciferase signal (Fig. 1F).

Given that Tiam1 can regulate the motility and invasion of tumor cells (15), we asked whether miR-10b regulation of Tiam1 affected migration and invasion. Expression of the miR-10b precursor in SUM159PT cells resulted in a 40% decrease in both migration and invasion as compared with nontargeting and mutant controls (Fig. 2A). Similarly, expression of the miR-10b vector inhibited the migration and invasion of both SUM159PT and 149PT cells significantly in comparison to expression of a control vector (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

miR-10b impedes cell migration and invasion. A, migration and Matrigel invasion assays of SUM-159PT cells transfected with nontargeting control miRNA, miR-10b mutant, or miR-10b precursor. *, p < 0.01. B, migration and Matrigel invasion assays of SUM-159PT and SUM-149PT cells infected either with miR-10b-expressing or empty vector retrovirus. *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.005. C, migration and Matrigel invasion assays of T47D cells and migration assay of MDA-MB-435 cells transfected with miR-10b antisense oligonucleotides. Antisense oligonucleotides directed against luciferase were used for negative control. *, p < 0.05. **, p < 0.005. Data for migration and invasion assays represent means ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

We next asked whether inhibition of endogenous miR-10b in T-47D and MDA-MB-435 cells would affect their motility. Indeed, expression of the miR-10b antisense oligonucleotide increased the migration and invasion of T-47D cells significantly (Fig. 2C). A similar effect of the miR-10b antisense oligonucleotide was seen for the migration of MDA-MB-435 cells (Fig. 2C).

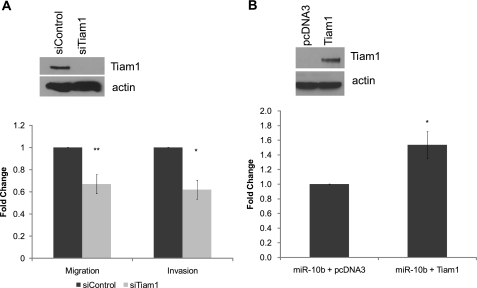

Next, we determined whether Tiam1 down-regulation is responsible for inhibition of cell motility by miR-10b. To determine whether SUM159PT cells are dependent on Tiam1 for cell motility, we silenced Tiam1 expression in these cells using a Tiam1 siRNA pool (Fig. 3A). Knockdown of Tiam1 resulted in a 40% decrease in both cell migration and cell invasion, similar to the change seen with de novo expression of miR-10b (Fig. 3A). Importantly, co-transfection of miR-10b and Tiam1 cDNA lacking the 3′-UTR was able to rescue miR-10b-induced repression of cell motility (Fig. 3B), suggesting that Tiam1 is a key factor responsible for decreased cell motility in cells expressing miR-10b.

FIGURE 3.

miR-10b regulates Tiam1-mediated motility. A, immunoblot of Tiam1 expression (upper panel) and migration and Matrigel invasion assays (lower panel) of SUM159PT cells transfected with either a Tiam1 siRNA pool or a control siRNA pool. *, p < 0.01. **, p < 0.001. Data for migration and invasion assays represent means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. B, immunoblot (upper panel) and migration assays (lower panel) of SUM159PT cells co-transfected with miR-10b and either a Tiam1 cDNA lacking the 3′-UTR or pcDNA3. *, p < 0.001. Data for migration and invasion assays represent means ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

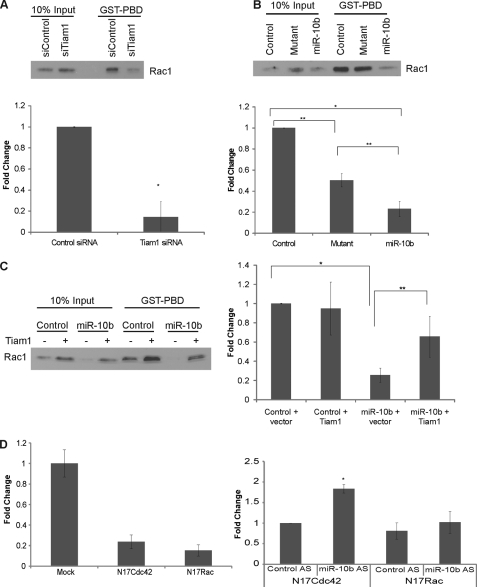

Given that Tiam1 is a GEF for Rac, we hypothesized that miR-10b-induced down-regulation of Tiam1 results in a corresponding decrease in Rac activation, thereby impairing cell motility. Decreasing Tiam1 expression in SUM159PT cells by siRNA resulted in a significant decrease in Rac activation (Fig. 4A), confirming that Tiam1 expression is necessary for optimal Rac activation. Similarly, de novo expression of miR-10b in this cell line also repressed activation of Rac as compared with both the non-targeting control and the miR-10b seed mutant (Fig. 4B). Co-transfection of miR-10b and Tiam1 cDNA partially rescued Rac activation (Fig. 4C), indicating that miR-10b represses cell motility in part via down-regulation of Tiam1, which leads to decreased activation of Rac.

FIGURE 4.

miR-10b represses Tiam1-dependent activation of Rac1. SUM159PT cells were transfected with either a Tiam1 siRNA pool or a control siRNA pool (A), with either nontargeting control miRNA, miR-10b mutant, or miR-10b precursor (B), or with nontargeting control miRNA or miR-10b precursor co-transfected with a Tiam1 cDNA lacking the 3′-UTR or empty vector pcDNA3 (C). Cell extracts were analyzed for Rac activation using the PBD assay as described under “Materials and Methods.” Graphs represent densitometric analysis of the band intensities ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.0005; **, p < 0.05. D, left graph. MDA-MB-435 cells were either mock transfected or transfected with dominant negative Rac and cdc42 constructs and assayed for migration. Right graph, MDA-MB-435 cells were assayed for migration after transfection with the miR-10b antisense or control oligonucleotides and the dominant negative Rac and cdc42 constructs as described under “Experimental Procedures.” *, p < 0.01.

The role of miR10b in regulating Rac was verified in MDA-MB-435 cells that express endogenous miR-10b. For this purpose, we used a dominant negative Rac construct (N17Rac), as well as a dominant negative Cdc42 construct (N17Cdc42) for comparison. Expression of either of these constructs inhibited the ability of MDA-MB-435 cells to migrate significantly (Fig. 4D, left panel). The ability of the miR-10b antisense oligonucleotide to increase the migration of MDA-MB-435 cells (see Fig. 2C) was abrogated by expression of N17Rac. In contrast, expression of N17Cdc42 was unable to abrogate this increase in migration caused by inhibiting miR-10b (Fig. 4D; right panel). These data argue that the ability of miR-10b to regulate migration is Rac-dependent.

DISCUSSION

We conclude from our data that Tiam1, a Rac GEF, is a target of miR-10b and that miR-10b-mediated regulation of Tiam1 in breast carcinoma cell lines influences Rac activation, migration, and invasion. These data support the emerging hypothesis that Rho GTPase signaling can be regulated by specific miRs (e.g. Ref. 19). Given that a single miR can regulate the expression of multiple proteins, however, the ability of miR-10b to target Tiam1 and influence Tiam1-mediated functions likely is to be dependent on multiple factors including cell type, pattern of miR expression and signals that regulate Tiam1 expression and function. It is intriguing to note, however, that inhibition of miR-10b function in breast carcinoma cells is sufficient to increase their migration and that this increase in migration is Rac-dependent (Fig. 4D), suggesting that Tiam1 is a key target of miR-10b in this context. In contrast to our findings, miR-10b was reported recently to promote the migration and invasion of human esophageal carcinoma cell lines by targeting KLF4, a tumor suppressor gene for esophageal carcinoma (20). These opposing findings substantiate the hypothesis that the function of specific miRNAs can differ markedly depending on oncogenic context (21).

Although Tiam1 expression correlates with breast cancer grade and progression (16, 17), little is known about how this GEF is regulated in breast tumors. The ability of miR-10b to target Tiam1 provides one such mechanism, which is substantiated by the observation that miR-10b expression in human breast carcinomas correlates inversely with tumor size and grade (22). Our data, however, must be considered in the context of the report that miR-10b promotes the migration and invasion of breast carcinoma cells and that it is causally associated with metastasis (11). In this important study, HoxD10 was identified as miR-10b target and it was proposed that HoxD10 represses expression of RHOC, which has been implicated in tumor invasion and metastasis. The ability of miR-10b to target HoxD10 could be significant, given the observation that this homeobox gene may have tumor suppressive functions in breast cancer (23). However, we question the purported role of miR-10b in inducing RhoC expression because SUM149PT and SUM159PT cells, which lack miR-10b expression (see Fig. 1 and Ref. 11) express relatively high levels of RHOC (24, 25) indicating that RHOC can be expressed in breast carcinoma cells in the absence of miR-10b. Clearly, miR-10b has significant effects on cellular functions that underlie the progression of breast and other cancers including RhoGTPase regulation, migration, and invasion. The challenge ahead is to resolve some of the discrepant observations that exist and unify the current data into a coherent mechanism of miR-10b function within the same tumor type.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phillip Zamore, Michael Horwich, Victor Ambros, Sharon Cantor, Roger Davis, and Leslie Shaw for discussions and advice and Kathleen O'Connor for the Tiam1 construct and guidance regarding Rac activation assays.

Footnotes

- miRNA

- microRNA

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- GEF

- guanidine exchange factor

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartel D. P. (2004) Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozen M., Creighton C. J., Ozdemir M., Ittmann M. (2008) Oncogene 27, 1788–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iorio M. V., Ferracin M., Liu C. G., Veronese A., Spizzo R., Sabbioni S., Magri E., Pedriali M., Fabbri M., Campiglio M., Ménard S., Palazzo J. P., Rosenberg A., Musiani P., Volinia S., Nenci I., Calin G. A., Querzoli P., Negrini M., Croce C. M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 7065–7070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calin G. A., Croce C. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 857–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu J., Getz G., Miska E. A., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Lamb J., Peck D., Sweet-Cordero A., Ebert B. L., Mak R. H., Ferrando A. A., Downing J. R., Jacks T., Horvitz H. R., Golub T. R. (2005) Nature 435, 834–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korpal M., Lee E. S., Hu G., Kang Y. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14910–14914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burk U., Schubert J., Wellner U., Schmalhofer O., Vincan E., Spaderna S., Brabletz T. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 582–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavazoie S. F., Alarcón C., Oskarsson T., Padua D., Wang Q., Bos P. D., Gerald W. L., Massagué J. (2008) Nature 451, 147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Q., Gumireddy K., Schrier M., le Sage C., Nagel R., Nair S., Egan D. A., Li A., Huang G., Klein-Szanto A. J., Gimotty P. A., Katsaros D., Coukos G., Zhang L., Puré E., Agami R. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu S., Wu H., Wu F., Nie D., Sheng S., Mo Y. Y. (2008) Cell Res. 18, 350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma L., Teruya-Feldstein J., Weinberg R. A. (2007) Nature 449, 682–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sander E. E., ten Klooster J. P., van Delft S., van der Kammen R. A., Collard J. G. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 1009–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benard V., Bohl B. P., Bokoch G. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13198–13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw L. M., Rabinovitz I., Wang H. H., Toker A., Mercurio A. M. (1997) Cell 91, 949–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michiels F., Habets G. G., Stam J. C., van der Kammen R. A., Collard J. G. (1995) Nature 375, 338–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minard M. E., Kim L. S., Price J. E., Gallick G. E. (2004) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 84, 21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam L., Vadlamudi R. K., McCrea P., Kumar R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28443–28450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2005) Cell 120, 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S. Y., Lee J. H., Ha M., Nam J. W., Kim V. N. (2009) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian Y., Luo A., Cai Y., Su Q., Ding F., Chen H., Liu Z. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7986–7994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebeshuber C. A., Zatloukal K., Martinez J. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gee H. E., Camps C., Buffa F. M., Colella S., Sheldon H., Gleadle J. M., Ragoussis J., Harris A. L. (2008) Nature 455, E8–9; author reply E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrio M., Arderiu G., Myers C., Boudreau N. J. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 7177–7185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson K. J., Dugan A. S., Mercurio A. M. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 8694–8701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleer C. G., Griffith K. A., Sabel M. S., Gallagher G., van Golen K. L., Wu Z. F., Merajver S. D. (2005) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 93, 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]