Abstract

The human mixed lineage leukemia-5 (MLL5) gene is frequently deleted in myeloid malignancies. Emerging evidence suggests that MLL5 has important functions in adult hematopoiesis and the chromatin regulatory network, and it participates in regulating the cell cycle machinery. Here, we demonstrate that MLL5 is tightly regulated through phosphorylation on its central domain at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Upon entry into mitosis, the phosphorylated MLL5 delocalizes from condensed chromosomes, whereas after mitotic exit, MLL5 becomes dephosphorylated and re-associates with the relaxed chromatin. We further identify that the mitotic phosphorylation and subcellular localization of MLL5 are dependent on Cdc2 kinase activity, and Thr-912 is the Cdc2-targeting site. Overexpression of the Cdc2-targeting MLL5 fragment obstructs mitotic entry by competitive inhibition of the phosphorylation of endogenous MLL5. In addition, G2 phase arrest caused by depletion of endogenous MLL5 can be compensated by exogenously overexpressed full-length MLL5 but not the phosphodomain deletion or MLL5-T912A mutant. Our data provide evidence that MLL5 is a novel cellular target of Cdc2, and the phosphorylation of MLL5 may have an indispensable role in the mitotic progression.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Cell Cycle, Mitosis, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Translocation, Cdc2, MLL5

Introduction

Aberrations in chromosome 7, either due to monosomy or partial deletion of 7q, are commonly associated with myeloid malignancies, including myelodyplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and therapy-induced myeloid neoplasms (1, 2). Cytogenetic studies have delineated 7q22 as a critical region in myeloid malignancies (3–5). A search for a candidate tumor suppressor gene within this region led to the identification of a novel gene, which was later categorized as the fifth MLL/trithorax member and designated MLL5 (6). MLL1 (also known as ALL-1, HRX, and Htrx), a frequent target of chromosomal translocation in myeloid and lymphoid leukemia, is the best characterized member of the MLL protein family (7–9). Mll1 and Mll2 knock-out mice are embryonic lethal (10, 11). Mice carrying mutant Mll3 genes are partially embryonic lethal, and surviving mice are stunted in overall growth (12). Recent studies on Mll5 knock-out mice have revealed that MLL5 plays a critical role in adult hematopoiesis and appears to be dispensable for embryonic development (13–16). Although Mll5 knock-out mice do not have an increased incidence of tumors, they suffer from mild growth retardation, male infertility, and compromised immunity. Nonetheless, the physiological function of MLL5 and its cellular targets remain elusive.

A common feature of the MLL protein family is the concomitant presence of a variable number of PHD3 (plant homeodomain) zinc fingers and a single SET (Su (var) 3–9, enhancer-of-zeste and trithorax) domain. Reports have shown that PHD fingers are binding or recognition modules for histone modification (17), whereas the SET domain possesses methyltransferase activity (18, 19). MLL1 and MLL2 form a protein complex containing menin, WDR5, and chromatin-remodeling components and are implicated in the regulation of Hox gene expression (20–22). MLL3 and MLL4/ALR are found in complexes containing ASC-2 (12) where their histone lysine methyltransferase activities are often associated with H3 acetylation and H3K27 demethylation (23, 24). Whether MLL5 possesses the histone lysine methyltransferase activity is still highly debatable. Several reports suggested that MLL5 lacks such intrinsic methyltransferase activity (14, 25). However, a short N-terminal isoform of MLL5 that contains both the PHD and SET domain was recently identified in a multisubunit complex in association with nuclear retinoic acid receptor-α (26), in which the isoform acts as a mono- and dimethyltransferase to H3K4.

MLL5 is widely expressed and evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammals. A recent gene-trap study found that MLL5 regulates a transcriptional mechanism that prevents inappropriate expression of S phase-promoting genes in quiescent cells (25, 27). The intricate interplay between MLL family members and the cell cycle machinery has also been documented (28–30). Tightly controlled biphasic expression of MLL1 is conferred by specialized E3 ligases to ensure orchestrated G1/S phase entry and M phase progression (28, 29). HCF1 recruits MLL1 H3K4 methylase to E2F-responsive promoters for transcriptional activation during the G1/S phase transition (30). Knockdown of MLL4/ALR resulted in reduced growth kinetics and impaired adhesion-related cytoskeletal activities (31). We have previously reported that overexpression or knockdown of MLL5 impeded cell cycle progression, leading us to propose that MLL5 participates in the cell cycle regulatory network at multiple stages of the cell cycle (32, 33). In this study, we further examine its cellular regulatory role at G2/M phase transition and show that MLL5 is phosphorylated at the Thr-912 residue by Cdc2 at the G2/M boundary. The phosphorylated MLL5 dissociated from the condensed mitotic chromosomes and the inhibition of MLL5 phosphorylation obstructed mitotic entry. In addition, G2 arrest caused by the depletion of endogenous MLL5 could be rescued by exogenous expression of the full-length MLL5 but not the phosphorylation-deficient mutants. Taken together, these results demonstrate that MLL5, a novel substrate of Cdc2, needs to be phosphorylated, and its dissociation from chromatin at G2/M transition is essential for proper mitotic progression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction and Transfection

MLL5 deletion mutants were generated by flanking each PCR fragment of MLL5 cDNA with the FLAG sequence and cloning the fragments into the pEF6/V5-His-TOPO vector (catalog no. K9610-20, Invitrogen) in-frame with BamHI and XbaI sites. The CD-4 domain was cloned into the pEGFP-C1 vector (catalog no. 6085-1, Clontech) for GFP fusion protein expression in HEK 293T cells and cloned into pGEX-4T3 vector (catalog no. 27-4583-01, Amersham Biosciences) for the GST fusion recombinant protein expression in the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) strain. Plasmid transfection was performed using the TransIT-LT1 (catalog no. MIR2300, Mirus) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Depletion of endogenous MLL5 was achieved by transfection of small interfering RNAs (number 3, sense, 5′-CAGCCCUCUGCAAACUUUCAGAAUUdTdT, and antisense, 5′-AAUUCUGAAAGUUUGCAGAGGGCUGdTdT; number 4: sense, 5′-GCACUGGUUGGGCAUUUUAdTdT, and antisense, 5′-UAAAAUGCCCAACCAGUGCdTdT), which have been described previously (33) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (catalog no. 13778-150, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell Culture and Synchronization

Human cervical carcinoma HeLa, osteosarcoma U2OS, colorectal carcinoma HCT116, and embryonic kidney HEK 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mm l-glutamine at 37 °C with 5% CO2 (hereafter referred to as complete medium). HeLa cells were synchronized to G2/M phase by blocking with 2 mm thymidine (catalog no. T1895, Sigma) for 18 h, released in complete medium for 4 h, and then incubated in 100 ng/ml nocodazole (catalog no. M1404, Sigma) for 12 h. The HEK 293T, U2OS, and HCT116 cells were synchronized to G2/M by incubation with 100 ng/ml nocodazole, taxol (catalog no. T7402, Sigma), or vinblastine (catalog no. V1377, Sigma) for 16 h. For G1/S phase synchronization, HeLa cells were incubated with thymidine for 18 h, released for 9 h, and again incubated with thymidine for 18 h. G2 phase synchronization for HeLa and HEK 293T cells was achieved by incubation with 10 μm RO-3306 (catalog no. 217699, Calbiochem) for 16 h.

Cell Lysate Preparation, Immunoprecipitation, and Phosphatase Treatment

Asynchronous or mitotic cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Antibodies for cyclin A (sc-751), cyclin B1 (sc-245), phosphohistone H3Ser10 (sc-8656-R), Cdc2 (sc-51578), and α-actin (sc-1616) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phospho-Ser/Thr (catalog no. 05-368) and phospho-Tyr (catalog no. 16105) antibodies were from Upstate, and phospho-Cdc2 (Tyr-15) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (catalog no. 9111). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against MLL5 had been described previously (33). Anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies were purchased from Thermo Scientific (catalog no. 31238), Jackson ImmunoResearch (catalog no. 115005174), and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-2020). For immunoprecipitation studies, cells were lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 5 mm NaF). Lysates were precleared by protein A/G-agarose beads (catalog no. sc-2001 and sc-2002, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 15 min on ice. Precleared lysate was then incubated with anti-FLAG (catalog no. F3165, Sigma) or anti-MLL5 antibodies at 4 °C for 2 h, followed by a 1-h incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads. The immune complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer before elution with Laemmli sample buffer. Mitotic HeLa lysate was treated with 10 units of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (catalog no. M0290S, New England Biolabs) in the presence or absence of 10 mm Na3VO4 and 5 mm NaF. The reaction was performed at 37 °C for 30 min before analysis.

GST Pulldown and in Vitro Kinase Assay

Expression of GST-CD-4 was induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside in E. coli at 30 °C for 3 h, followed by purification with glutathione S-Sepharose beads (catalog no. 17-0756-01, Amersham Biosciences). The in vitro kinase assay was conducted at 30 °C for 30 min in a kinase buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm ATP, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 10 μCi of [32P]ATP (catalog no. NEG520A250UC, PerkinElmer Life Sciences)), 10 units of active Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex (catalog no. V2891, Promega), and 4 μg of GST or GST-CD-4. Histone H1 (catalog no. H5505, Sigma) was used as a positive control. Samples were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Subcellular Protein Fractionation

The fractionation was done essentially as described previously (34). In brief, HeLa cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS before being resuspended in cytosolic buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 340 mm sucrose, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 5 mm NaF) to a final concentration of 4 × 107 cells/ml. After a 5-min incubation on ice, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1300 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and saved as cytosolic protein fraction. The pellet was washed twice with cytosolic buffer and then lysed in nuclear lysis buffer (3 mm EDTA, 0.2 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 5 mm NaF). The lysis reaction was incubated on ice for 20 min and then centrifuged at 1700 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and kept as nuclear protein fraction, and the final pellet was washed twice with nuclear lysis buffer, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, sonicated, and kept as the chromatin-associated protein fraction.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol on ice for at least 2 h and stained in propidium iodide solution (20 μg/ml propidium iodide (catalog no. P4170, Sigma), 100 μg/ml RNase A (catalog no. R6513, Sigma), and 0.1% Triton X-100). Cell cycle progression was analyzed by Epics Altra flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter), and the data were analyzed using ModFit LTTM.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Mitotic Index Determination

HEK 293T cells were grown on polylysine-coated coverslips and transfected with MLL5 siRNA number 4 for 24 h, followed by overexpression of FLAG-MLL5, FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4, and FLAG-MLL5-T912A for 8 h. Transfected cells were synchronized to G2 phase by incubating with 10 μm RO-3306 for 16 h. G2 arrest cells were released for mitotic entry by washing out the RO-3306 and re-incubated with complete medium containing 100 ng/ml nocodazole. At 0, 20, 50, and 90 min post-release, coverslips were fixed with methanol at −20 °C for 10 min, rehydrated with PBS, and blocked in PBS, 5% bovine serum albumin. Primary antibodies (anti-FLAG and anti-phosphohistone H3Ser10) were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Samples were then washed with PBS, 0.05% Tween 20 three times and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 (catalog no. A21441 or A11004, Invitrogen) for 1 h. After washing off the unbound secondary antibodies, DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (catalog no. D1306), and the coverslips were mounted with FluorSave reagent (catalog no. 345789, Merck). Mitotic index was assessed by calculating the percentage of phosphohistone H3Ser10-positive cells, and at least 80 cells were counted for each sample in each time point. Images were acquired using inverted fluorescence microscopy (Olympus) equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (QImaging) and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (MediaCybernetics).

RESULTS

MLL5 Displays Slower Gel Mobility at the G2/M Phase Boundary

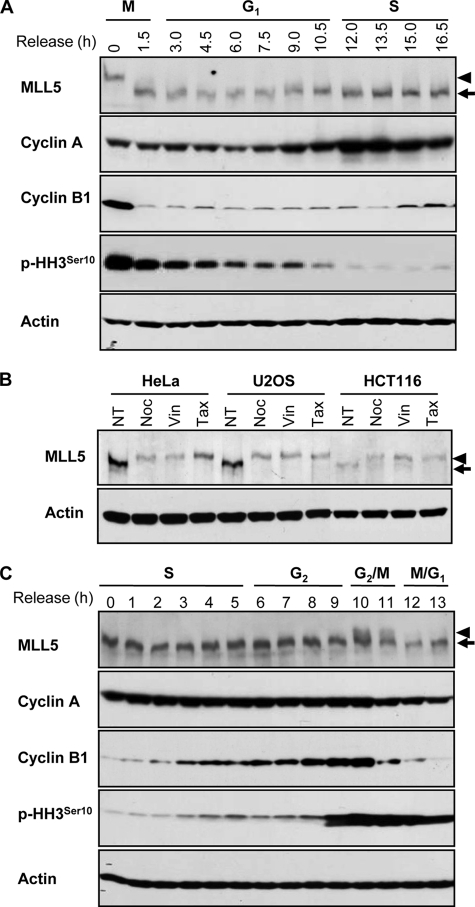

MLL5 forms intranuclear foci and both its up- and down-regulation inhibits cell cycle progression (32, 33). To further understand the potential role of MLL5 in cell cycle regulation, we investigated the expression of endogenous MLL5 throughout the cell cycle. HeLa cells were released from the G2/M boundary, and the progression of the cell cycle was monitored by measuring the cellular DNA content. At each indicated time point, the whole cell lysate was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-MLL5 polyclonal antibody. MLL5 displayed slower gel mobility at the G2/M phase boundary but converted to a faster migrating form immediately after exit from mitosis (Fig. 1A). To ensure that the observed mobility change was not cell type-specific or due to drug treatment with nocodazole, HeLa, U2OS, or HCT116 cells were synchronized to the G2/M phase boundary with two other microtubule-depolymerizing drugs, vinblastine and taxol, and the gel mobility was assessed (Fig. 1B). Consistently, a similar decrease in the electrophoretic mobility of MLL5 was detected in all three cell lines, implying that MLL5 underwent certain post-translational modifications at the G2/M phase boundary. To further confirm the observation, HeLa cells were synchronized to the G1/S phase boundary by a double thymidine block, and the expression of endogenous MLL5 protein was examined at each indicated time point after release. Cell cycle progression was again monitored by measuring the cellular DNA content. The slower migrating form of MLL5 was detected between 10 and 11 h after release from the G1/S boundary, correlating with the increase in mitotic index (phosphorylation of histone H3Ser10) and the destruction of cyclin B1 (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the observations made at release from the G2/M boundary, these data demonstrated that the post-translational modification of MLL5 was reversible and coincided with mitotic progression.

FIGURE 1.

MLL5 displays slower gel mobility at G2/M transition. A, expression of MLL5 in HeLa cells released from the G2/M boundary. B, expression of MLL5 in asynchronous (no treatment (NT)) and G2/M-arrested HeLa, U2OS, and HCT116 cells. G2/M synchronization was achieved by treatment with nocodazole (Noc), vinblastine (Vin), or taxol (Tax). C, expression of MLL5 in HeLa cells that were released from G1/S synchronization. Cyclin A, cyclin B1, and phosphohistone H3Ser10 serve as cell cycle progression markers. Actin serves as a protein loading control. Arrows indicate MLL5, and arrowheads denote the slower migrating form of MLL5 at G2/M phase.

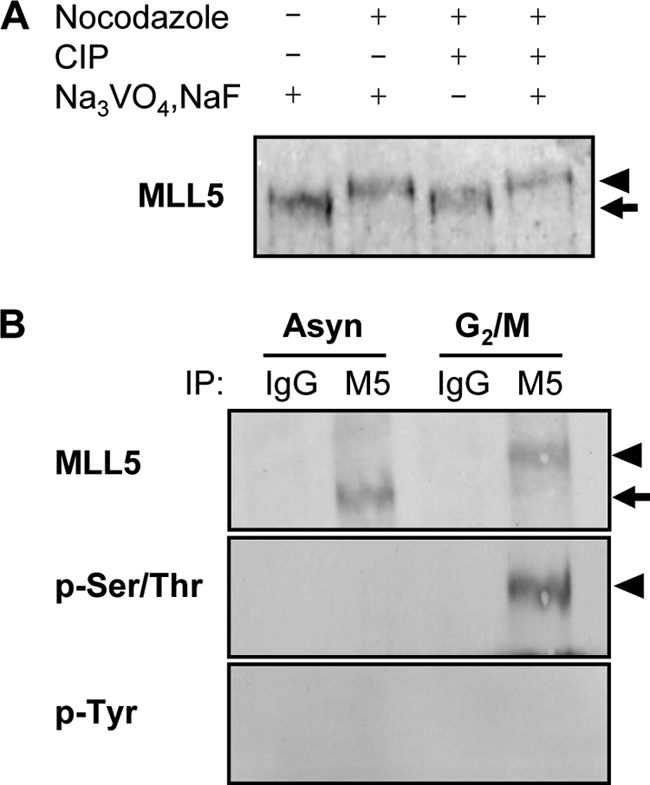

MLL5 Is Phosphorylated during Mitosis

Phosphorylation signaling is essential in the regulation of protein function, stability, localization, and protein-protein interactions. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation have been extensively studied. To investigate whether the slower migrating form of MLL5 was due to phosphorylation, mitotic extract of HeLa cells was subjected to phosphatase treatment in the presence or absence of phosphatase inhibitors. As shown in Fig. 2A, phosphatase treatment converted the slower migrating MLL5 in the mitotic extract to a faster migrating form as observed in the asynchronous cell extract. Moreover, this conversion was markedly blocked by phosphatase inhibitors, suggesting that the decreased gel mobility of MLL5 was likely due to phosphorylation. The observation was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation of the endogenous MLL5 from either asynchronous or mitotic HeLa cell lysates. A mitosis-specific phosphorylation signal was detected by anti-phospho-Ser/Thr antibodies but not anti-phospho-Tyr antibodies (Fig. 2B). The same blot was re-probed with anti-MLL5 antibodies to ensure equal loading. However, the possibility of MLL5 being phosphorylated on tyrosine residues cannot be ruled out completely, because an undetectable phospho-Tyr signal might result from less abundant tyrosine residues on MLL5 or inadequate sensitivity of Western blotting.

FIGURE 2.

MLL5 is phosphorylated at Ser/Thr residues at G2/M phase. A, alkaline phosphatase treatment of G2/M-arrested HeLa cell extract converted MLL5 to a faster migrating form that ran to the same migrating position as in the asynchronous cell extract. CIP, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. B, endogenous MLL5 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from asynchronous or G2/M-arrested HeLa cell extracts. Phosphorylated MLL5 (arrowheads) is present at G2/M phase and can be detected by anti-phospho-Ser/Thr but not anti-phospho-Tyr antibodies.

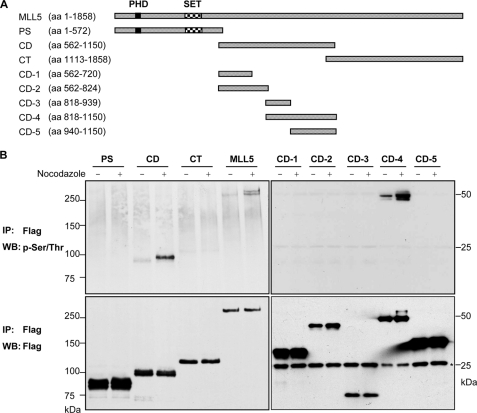

Central Domain of MLL5 Is Phosphorylated at Mitosis

To identify which of the functional domains of MLL5 is responsible for mitosis- dependent phosphorylation, three deletion mutants of MLL5, consisting of the PHD and SET domains, the central domain, or the C-terminal domain, were constructed and N-terminally tagged with a FLAG epitope (Fig. 3A). All these truncated domains contained at least one nuclear localization signal to ensure a correct nuclear expression. Nocodazole was added into the culture medium 24 h post-transfection for G2/M synchronization, followed by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Only the full-length MLL5 protein and the central domain were detectable by anti-phospho-Ser/Thr antibodies, and the phosphorylation modification was greatly increased in the presence of nocodazole (Fig. 3B, left panel). To further delineate the target site of phosphorylation, the central domain was dissected into smaller fragments (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, Western blotting revealed that the phosphorylation signal on the CD-4 (amino acid 818–1150) domain was greatly enriched upon nocodazole treatment (Fig. 3B, right panel). There was no detectable phosphorylation signal for either CD-3 or CD-5 constructs, implying that the CD-4 fragment comprised a certain conformation that must be kept intact for mitotic phosphorylation.

FIGURE 3.

CD-4 domain of MLL5 is sufficient to mediate mitotic phosphorylation. A, schematic representation of MLL5 and deletion fragments; PS, PHDSET domain; CD, central domain; CT, C-terminal domain. The central domain was further dissected into CD-1, CD-2, CD-3, CD-4, and CD-5. aa, amino acids. B, full-length MLL5 and various deletion mutants were immunoprecipitated (IP) from untreated or nocodazole-synchronized HEK 293T cell lysates with anti-FLAG antibodies and detected by anti-phospho-Ser/Thr or anti-FLAG antibodies. MLL5 was phosphorylated at Ser/Thr residues on the CD-4 domain at G2/M phase. The numbers indicate the molecular masses (kDa) of the protein standards, and the asterisk denotes the light chain of antibodies. WB, Western blot.

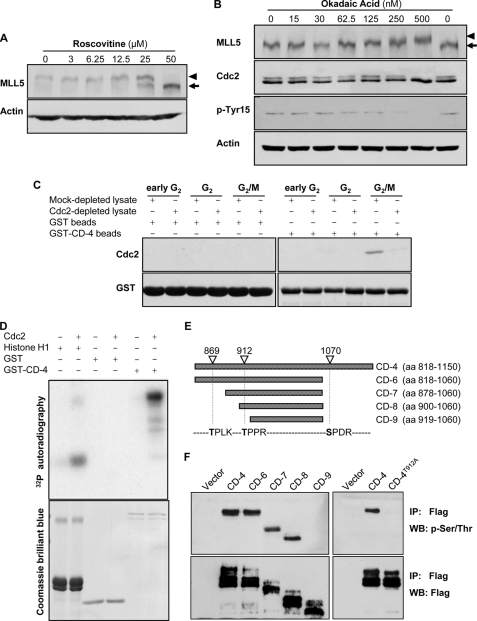

MLL5 Is Phosphorylated by Cdc2 in Vitro

Given that the Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex is the major component of the maturation-promoting factor that drives the mitotic progression (35–37), we first tested whether phosphorylation of MLL5 was affected by the Cdc2 inhibitor roscovitine or its activator okadaic acid (38, 39). When mitotic HeLa cells were treated with increasing concentrations of roscovitine, a de-phosphorylated form of MLL5 was observed in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). This suggests that the inhibition of Cdc2 activity attenuates the phosphorylation of MLL5 during mitosis. Okadaic acid, a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A, is known to induce the activation of Cdc2 through the phosphorylation of Cdc25, leading to de-phosphorylation of Cdc2 at Tyr-15. Indeed, when asynchronous HeLa cells were treated with okadaic acid, an increase in MLL5 phosphorylation was observed concomitantly with the activation of Cdc2, as indicated by the de-phosphorylation of Cdc2 at Tyr-15 (Fig. 4B). Next, a GST pulldown assay was employed to examine the interactions, if any, between MLL5 and Cdc2 (Fig. 4C). Purified GST-CD-4 glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with HeLa cell lysates, which were extracted after 8, 10, or 12 h of release from G1/S boundary, corresponding to the early G2, G2 and G2/M phases, respectively. Results demonstrated that GST-CD-4, but not GST, can be co-purified with Cdc2 only in the cell extract of the G2/M phase. The interactions diminished significantly when the extracts were depleted of Cdc2 by pre-clearing with anti-Cdc2 antibodies (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these data suggested that Cdc2 may be a likely kinase for MLL5 mitotic phosphorylation. We then explored the possibility that the Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex can phosphorylate GST-CD-4 domain in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4D, Cdc2-cyclin B1 was able to specifically confer 32P to CD-4 and histone H1 but not to GST. The data demonstrate that the central region of MLL5 (CD-4 domain) is a substrate of the Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex.

FIGURE 4.

MLL5 is phosphorylated by Cdc2 at G2/M. A, mitotic HeLa cells were treated with various concentrations of roscovitine for 4 h in the presence of nocodazole. The phosphorylation of MLL5 was inhibited by roscovitine in a dose-dependent manner. B, asynchronous HeLa cells were treated with various concentrations of okadaic acid for 4 h. The phosphorylation of MLL5 was gradually induced by okadaic acid in a dose-dependent manner. C, GST-CD-4 protein co-purified with Cdc2 in HeLa cells that were released from the G1/S phase boundary for 12 h (G2/M). D, upper panel, GST-CD-4 was phosphorylated by human recombinant Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex in an in vitro kinase assay. Histone H1 and GST served as a positive and a negative control, respectively. Lower panel, Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining for histone H1, GST, and GST-CD-4. E, schematic representation of MLL5-CD-4 domain and its deletion fragments. The potential Cdc2 targeting sites on MLL5-CD-4 domain are denoted based on the consensus motif for Cdc2 kinase ((S/T)PX(K/R)). aa, amino acids. F, left panel, CD-4 domain and deletion mutants (CD-6–9) with sequential deletion of Cdc2-targeting sites were immunoprecipitated (IP) from nocodazole-synchronized extract of HEK 293T cells using anti-FLAG antibodies and detected by anti-phospho-Ser/Thr or anti-FLAG antibodies. The phosphorylation on MLL5 is abrogated when Thr-912 residue was deleted. Right panel, mutation of Thr-912 to Ala on the CD-4 domain eliminated the phosphorylation modification, suggesting that Thr-912 is the phosphorylation targeting site by Cdc2. WB, Western blot.

To gain information on the consequence of the phosphorylation modification by Cdc2, we proceeded to determine the phosphorylation site on MLL5. The amino acid sequence of CD-4 domain was examined, and 21 Ser/Thr-Pro motifs were found within this region. Among these Ser/Thr-Pro motifs, three of them fit to the Cdc2 consensus motif (S/T)PX(K/R) (Fig. 4E) (40). Based on the sequence analysis, we further constructed MLL5 fragments that include sequential deletion of the putative Cdc2-targeting sites, and we tested whether the mitotic phosphorylation of these fragments can be abolished. As shown in Fig. 4F, left panel, removal of Ser-1070 (CD-6) or Thr-869 (CD-7 and CD-8) did not affect the phosphorylation of MLL5 in mitotic cells, although deletion of the Thr-912 site (CD-9) completely eliminated the mitotic phosphorylation on MLL5. This result suggested that the Thr-912 residue is critical for the mitotic phosphorylation of MLL5. Next, site-directed mutagenesis was carried out, and the Thr-912 residue on the CD-4 domain was replaced by Ala. Immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the CD-4T912A domain was unable to be phosphorylated upon nocodazole treatment (Fig. 4F, right panel). Taken together, these findings imply that the Thr-912 residue of MLL5 is a targeting site for Cdc2 phosphorylation in mitosis.

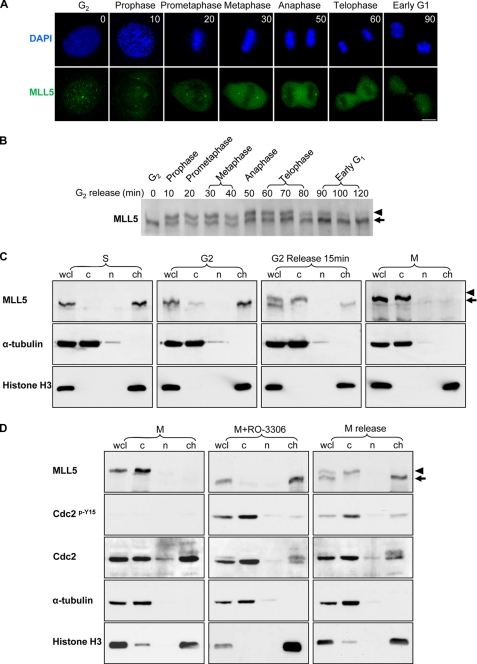

Dynamic Changes in Phosphorylation and Subcellular Localization of MLL5 during Mitosis

To elucidate the functional significance of the phosphorylation modification of MLL5, we carried out a time course study by monitoring the MLL5 phosphorylation status during the late G2 phase to G2/M transition in synchronized HeLa cells. A specific and reversible Cdc2 inhibitor RO-3306 was used to synchronize HeLa cells to the G2 phase (41). After release, mitotic progression was monitored by examining the DNA structure. The subcellular localization and the phosphorylation modification of MLL5 were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 5A, MLL5 formed nuclear speckles at the G2 phase (time 0). After 10 min of release, chromatin started to compact, and MLL5 speckles were dissolved. The disappearance of nuclear speckles coincided with the phosphorylation of MLL5 as shown by the retarded gel migration using Western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). When chromatin further condensed and the nuclear envelop broke down, MLL5 was excluded from chromosomes, resulting in cytosolic localization. As mitosis progressed, MLL5 was kept in a phosphorylated state and delocalized from condensed chromosomes. Until the DNA in the daughter cells started to relax, MLL5 was found to be dephosphorylated and re-localized to the nucleus at 90 min after release. Taken together, these data imply that the phosphorylation status of MLL5 regulates its cellular distribution at mitosis. To further examine the correlation between the phosphorylation of MLL5 and its subcellular localization, HeLa cells were synchronized to different cell cycle stages and were fractionated into cytoplasmic, nucleoplasmic, and chromatin-associated fractions. In S and G2 phases, MLL5 mainly associated with chromatin (Fig. 5C). When G2-arrested cells were released for mitotic progression (15 min), ∼50% of total cellular MLL5 was phosphorylated, and the phospho-MLL5 was seen in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 5C). As in nocodazole-arrested mitotic cells, MLL5 was fully phosphorylated and excluded from the chromosomes. These results confirmed that the phosphorylated MLL5 exhibits a distinct and dynamic subcellular localization during mitosis.

FIGURE 5.

Phospho-MLL5 dissociates from mitotic chromosomes. HeLa cells were grown on coverslips, and G2-arrested cells were released into fresh medium. Samples for immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting were collected every 10 min. A, MLL5 formed intranuclear foci in G2 phase (time 0), but it dissociated from condensed chromosomes and displayed cytosolic staining pattern during mitosis (10 min, prophase; 20 min, prometaphase; 30 min, metaphase; 50 min, anaphase; and 60 min, telophase). When cells completed mitosis (90 min), MLL5 re-localized to the nucleus. Scale bar, 10 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. B, time course study on the phosphorylation of MLL5 during mitosis. C, HeLa cells were arrested at difference cell cycle stages, and cellular fractionation was performed. Cells arrested in S phase were collected after G1/S release for 4 h; G2 phase arrest was achieved by incubation with RO-3306 for 20 h, and M phase cells were synchronized by the Thy-nocodazole method. α-Tubulin and histone H3 were employed as cytoplasmic (c) and chromatin-associated (ch) protein marker, respectively, and nucleoplasmic protein was denoted as group (n). Whole cell lysate (wcl) serves as total cellular protein control. Phosphorylation and subcellular localization of MLL5 were examined by Western blotting. MLL5 was extracted in the chromatin fraction in S and G2 phase cells (1st and 2nd panel), and in mitotic cells the MLL5 was phosphorylated and extracted in the cytoplasmic fraction (3rd and 4th panels). D, mitotic phosphorylation and localization of MLL5 were dependent on Cdc2 kinase activity. In mitosis-arrested HeLa cells, MLL5 was phosphorylated and extracted in the cytoplasmic fraction (left panel). When mitotic HeLa cells were treated with RO-3306 for 1.5 h, MLL5 was dephosphorylated and extracted in the chromatin fraction. Inhibition of Cdc2 activity was revealed by the increase in phosphorylation of Cdc2 on Tyr-15 (middle panel). When mitotic cells were released into complete medium for 1.5 h and re-entered into the G1 phase, MLL5 was dephosphorylated and associated with chromatin (right panel). Phospho-MLL5 was denoted by an arrowhead.

To further substantiate the role of Cdc2-cyclin B1 in mediating the phosphorylation of MLL5, we questioned if inhibition of Cdc2 kinase activity could influence the phosphorylation and subcellular localization of MLL5 in mitosis. As shown in Fig. 5D, when cells were arrested in mitosis, MLL5 was phosphorylated and dissociated from mitotic chromosomes. Meanwhile, Cdc2 was kept in an active state because phosphorylation on Cdc2 was undetectable with the anti-pY15-Cdc2 antibody (left panel). However, when Cdc2 kinase activity was inhibited by RO-3306 in mitotic cells for 1.5 h (Fig. 5D, middle panel), the phosphorylated form of MLL5 was not detected in the whole cell lysate and cytosolic fraction, suggesting that MLL5 is de-phosphorylated upon inhibiting Cdc2 activity. Successful inhibition of Cdc2 activity was denoted by the increase in phosphorylation of Cdc2 on Tyr-15. The dephosphorylation of MLL5 was not due to mitotic exit as the RO-3306-treated mitotic cells remained at a DNA content of 4N (data not shown). When cells were released from the M phase, the G1 phase cells displayed a de-phosphorylated form of MLL5 and re-associated with chromatin (Fig. 5D, right panel). Altogether, our data suggest that the phosphorylation and localization of MLL5 are highly dependent on the activity of Cdc2.

Phosphorylation Modification of MLL5 and Mitotic Progression

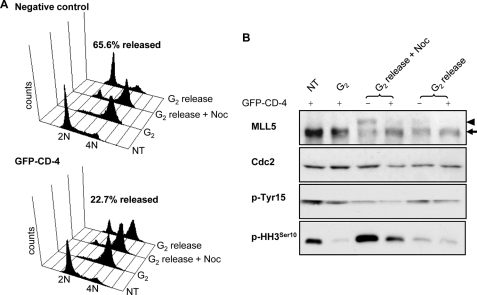

The above results demonstrate the phosphorylation modification of MLL5 regulates its cellular distribution. To further elucidate the functional consequences of MLL5 phosphorylation by Cdc2 on mitotic progression, we took advantage of the CD-4 domain that could be a competitive substrate of MLL5 for Cdc2 kinase. The GFP-fused CD-4 domain was expressed in HEK 293T cells in the presence of the G2-synchronizing drug RO-3306 for 20 h. Cells were then released in the presence or absence of nocodazole for 5 h before being harvested for Western blotting and cell cycle analysis. As shown in Fig. 6A, for both GFP-negative and GFP-CD-4 groups, the majority of cells was successfully synchronized at G2 phase by RO-3306. However, when G2-arrested cells were released into the medium containing nocodazole, a slower migrating phosphorylated form of MLL5 was detected in GFP-negative control cells but was barely seen in GFP-CD-4-expressing cells (Fig. 6B, 3rd and 4th lanes). This implies that overexpression of the CD-4 domain successfully blocked the mitotic phosphorylation of endogenous MLL5. We next asked if blocking the phosphorylation of endogenous MLL5 at the G2/M transition could affect mitotic progression. As shown in Fig. 6A, upper panel, when G2-synchronized cells were released for 5 h, a total of 65.6% GFP-negative control cells was able to pass through mitosis and re-enter into the G1 phase of the next cell cycle. In contrast, only 22.7% of GFP-CD-4-expressing cells were able to progress through mitosis and enter into the G1 phase, indicating impeded or delayed mitotic progression (Fig. 6A, lower panel). Indeed, a significant reduction in the phosphorylation of histone H3Ser10 was observed in GFP-CD-4-expressing cells (Fig. 6B), indicating that they encountered compromised mitotic entry. Notably, the failure of mitotic progression in GFP-CD-4-positive cells did not seem to be due to the loss of Cdc2 kinase activity, because no significant difference in the de-phosphorylation of Cdc2 at Tyr-15 was observed between GFP-negative and GFP-CD-4 cells (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of endogenous MLL5 phosphorylation impedes mitotic progression and arrests cells at the G2/M transition. HEK 293T cells were transfected with GFP-CD-4 in the absence (no treatment (NT)) or presence of RO-3306 for 20 h before release into complete medium or nocodazole-containing medium for 5 h. A, cell cycle analysis for GFP-negative control cells and GFP-CD-4-expressing cells. The percentage represents the population that successfully progressed through mitosis and re-entered G1 phase after 5 h release from G2 arrest. B, population of GFP-CD-4 positive or GFP-negative cells released from RO-3306 was sorted separately before harvesting for Western blotting. Phosphorylation of endogenous MLL5 at G2/M phase (G2 release + nocodazole (Noc)) was inhibited by ectopic overexpression of GFP-CD-4. Arrowhead indicates phospho-MLL5; arrow indicates MLL5.

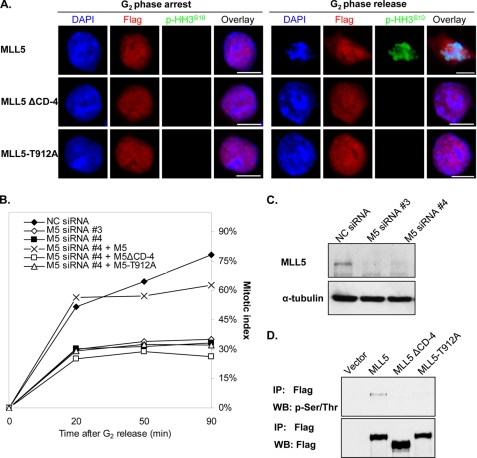

The above findings suggested that phosphorylation of MLL5 by Cdc2 might be a vital event associated with mitotic entry. This hypothesis prompted us to further investigate the causality between phosphorylation of MLL5 and mitotic progression. Recent studies on cell cycle progression have shown that the depletion of MLL5 by siRNA caused G1 and G2 arrests (33). We attempted to examine whether the phosphodomain deletion mutant (FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4) or FLAG-MLL5-T912A mutant could overcome the G2 arrest and compensate the cellular function from the loss of endogenous MLL5. To avoid the off-target effects, the endogenous MLL5 was knocked down by two different siRNA duplexes targeting at either coding region (siRNA number 3) or 3′-untranslated region (siRNA number 4), which have been described previously (33). The rescue experiment was performed in the group of cells transfected with siRNA number 4 because it was unable to affect the exogenously overexpressed FLAG-MLL5, FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4, or FLAG-MLL5-T912A mRNA. After 24 h of siRNA transfection, FLAG-MLL5, FLAG-MLL5 ΔCD-4, or FLAG-MLL5-T912A was introduced for 8 h, followed by treating with RO-3306 for another 16 h. To study the mitotic entry, cells were released into nocodazole-containing medium to assess the cumulative mitotic index at each indicated time point. Meanwhile, the localization of FLAG-MLL5 and the mutants was determined by immunofluorescence staining. As presented in Fig. 7A, FLAG-MLL5 localized to the nuclei in G2-synchronized cells. After release from G2 phase, it dissociated from condensed mitotic chromosomes that were marked by anti-phosphohistone H3Ser10 antibody. In contrast, FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 and FLAG-MLL5-T912A were found to reside in the nucleus in both G2 synchronized and released cells, and there was no phosphorylation on histone H3Ser10, suggesting that deficiency in phosphorylation restricted FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 and FLAG-MLL5-T912A to the nucleus and impeded the mitotic entry. Cumulative mitotic index was also recorded to quantify the rescue efficiency (Fig. 7B). In scrambled siRNA-transfected cells, the mitotic cells reached 78.3% after G2 release, although in the MLL5-knockdown cell, the percentage of G2 phase cells that could progress into mitosis was only 33–35%. If endogenous MLL5-depleted cells were transfected with the FLAG-MLL5 construct, the mitotic index was able to increase to 62.8%. In contrast, mitotic entry rates for FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4- and FLAG-MLL5-T912A-positive cells were only 26.4 and 32.1%, respectively. Knockdown efficiency of the endogenous MLL5 and the deficient phosphorylation of FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 and FLAG-MLL5-T912A were revealed by immunoblots in Fig. 7, C and D, respectively. Collectively, these data demonstrated that the wild type MLL5, but not the phosphorylation-deficient mutant, can rescue the G2 arrest caused by knockdown of endogenous MLL5.

FIGURE 7.

G2 arrest caused by the depletion of endogenous MLL5 can be rescued by exogenous expression of FLAG-MLL5 but not FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 or FLAG-MLL5-T912A. Endogenous MLL5 expression in HEK 293T cells were knocked down by siRNA, and FLAG-MLL5, FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4, or FLAG-MLL5-T912A was transfected to rescue the cell cycle arrest. Cells were synchronized to G2 phase and allowed for mitotic progression. MLL5 localization was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining using anti-FLAG antibodies. Mitotic index was calculated by counting the phosphohistone H3Ser10-positive cells at 20, 50, and 90 min post-release. A, FLAG-MLL5 protein dissociated from chromosomes and the cells entered mitosis after G2 release for 20 min, as shown by positive histone H3Ser10 staining and chromosome condensation (1st row). FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 and FLAG-MLL5-T912A were restricted in nuclei, and there was no visible chromatin condensation, which was marked by histone H3Ser10 phosphorylation. Scale bar, 10 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. B, cumulative mitotic index was calculated for control cells (NC siRNA), endogenous MLL5-knockdown cells (M5 siRNA #3 or M5 siRNA #4), FLAG-MLL5-positive cells (M5 siRNA #4 + M5), FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4-positive cells (M5 siRNA #4 + M5ΔCD-4), and FLAG-MLL5-T912A-positive cells (M5 siRNA #4 + M5-T912A). C, Western blotting showed the successful knockdown of endogenous MLL5 by siRNA numbers 3 and 4. D, immunoprecipitation result showed that FLAG-MLL5ΔCD-4 and FLAG-MLL5-T912A could not be phosphosphorylated upon nocodazole treatment.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have documented the dynamic phosphorylation modification on MLL5 during mitosis and the redistribution of phosphorylated MLL5 in mitotic cells. The phosphorylation and localization of MLL5 are dependent on the Cdc2 kinase activity. We further identified that the Thr-912 residue on MLL5 is important for the mitotic phosphorylation of MLL5 by Cdc2. In addition, ectopic overexpression of the Cdc2 targeting domain obstructs mitotic progression, likely through competitive inhibition of endogenous MLL5. The functional importance of phosphorylation modification is revealed by the inability of the MLL5ΔCD-4 and MLL5-T912A mutants to compensate for the loss of endogenous MLL5. We have previously shown that MLL5 participates in the cell cycle regulatory machinery at multiple stages of the cell cycle (33). The data presented here further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of MLL5 in the G2/M transition. So far, this is the only report on cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation regulation among MLL family members. The precursor MLL1 undergoes evolutionarily conserved site-specific cleavage by Taspase1. Following processing, C-terminal MLL appears to undergo phosphorylation (42). However, the regulation of MLL phosphorylation and the functional consequence of such phosphorylation remain undetermined.

Although alteration of the electrophoretic mobility of a target protein upon phosphorylation modification has been well documented, it is still quite surprising that a change in gel mobility for such a big protein (>200 kDa) could be detected by a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. One possible explanation is that the addition of a phosphate group on MLL5 not only makes changes to the molecular mass but alters the conformation of the protein, causing differential denaturation by SDS and thus inducing changes in the migration of the protein that is not strictly in line with molecular mass (43). Another possible explanation is that numerous Ser and Thr residues clustered within the CD-4 domain are phosphorylated at mitosis. Indeed, the 333-residue CD-4 domain is rich in Ser and Thr (38 Ser and 35 Thr residues). Although in this study Thr-912 was identified to be a critical Cdc2-targeting site as the mutation of Thr to Ala completely abrogated the mitotic phosphorylation of MLL5, the possibility that additional phosphorylation by other kinases may occur upon Thr-912 phosphorylation cannot be ruled out. Hence, for such a Ser/Thr-rich region, high resolution mass spectrometry will be a more systematic approach to map out the phosphorylation sites on MLL5 in mitosis (44).

Cdc2 is the main mitotic kinase controlling the onset of mitosis by phosphorylating a range of substrates involved in mitotic activation, nuclear envelope breakdown, chromosome assembly, and mitotic spindle formation. Studies have shown that phosphorylation by Cdc2 may create a docking site for other mitotic kinases, such as PLK1 to regulate mitotic progression in later stages (45, 46). Therefore, phosphorylation on the Thr-912 residue by Cdc2 may serve as a priming site on MLL5, leading to the recruitment of other mitotic kinases to participate in the downstream phosphorylation events. Upon phosphorylation, MLL5 may undergo subsequent post-translational modifications that are phosphorylation-dependent. Growing evidence has highlighted a crucial role of phosphorylation modification in signal transduction and cross-talk with other protein post-translational modifications (47). Further investigation of subsequent mitotic events upon phosphorylation of Thr-912 on MLL5, and the de-phosphorylation mechanism of MLL5 at the mitotic exit, will address in greater detail how the mitotic cascade is regulated.

MLL5 has been implicated in the cell cycle and differentiation regulation via directly binding to the regulatory region of a target gene or indirectly modulating a hierarchy of chromatin and transcriptional regulators (25). The mitotic phosphorylation modification appears to lead to the subcellular redistribution of MLL5, perhaps to prevent it from reaching downstream targets while repressing the interphase transcriptional program. Indeed, at the onset of mitosis, many transcriptional and chromatin remodeling factors are excluded from chromatin, which correlated with global transcriptional silencing and chromosome condensation (48). A common mechanism involved in the chromosomal exclusion is the intrinsic and systematic modifications on histone H3 protein, which facilitates chromatin condensation and confers the topological specificity to mitotic chromosomes (49, 50). Studies on MLL1 in the cell cycle demonstrate that in interphase MLL1 coordinates the expression of cyclins to ensure proper cell cycle transition (30) and the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors to suppress cell proliferation (51). In mitosis, most of MLL1 and MLL1-interacting proteins (CGBP, Ash2, and Rbbp5) dissociate from condensed chromatin and spread into the cytoplasm, except a small amount of MLL1 is still associated with the actively transcribed Hox gene promoter (52). A genome-wide RNA interference profiling study has suggested that MLL5 may form a protein complex, homologous to the yeast ortholog SET3 complex, with NcoR2 and TLB1X functioning as transcription repressors during cytokinesis (53). It is plausible that the phosphorylation modification on MLL5 may serve as a “molecular switch” to signal the protein complex to dissociate from mitotic chromosomes to turn on the mitotic program. Previous studies on the cell cycle suggest that overexpression or down-regulation of MLL5 inhibits cell proliferation possibly via modulating p21 and pRb pathways (33). This study demonstrates that perturbation in MLL5 phosphorylation, either by overexpression of phosphodomain deletion or T912A mutant, associates with impaired mitotic progression. Collectively, these data imply that the cell cycle regulatory function of MLL5 not only depends on protein abundance but also relies on post-translational modification.

Although the histone methyltransferase activity of MLL5 has yet to be fully characterized, a recent report by Fujiki et al. (26) suggested that a short isoform but not the full-length MLL5 possesses GlcNAcylation-dependent histone lysine methyltransferase activity, facilitating retinoic acid-induced granulopoiesis. Therefore, tightly regulated phosphorylation of MLL5 during mitosis may coordinate with its mitotic chromatin regulatory roles to ensure proper mitotic progression. It will be intriguing to test whether such a phosphorylation signal may be a fine-tuning factor for its epigenetic activity. As demonstrated by Sampath et al. (54), autocatalytic methylation of H3K9 G9a methylase is necessary to mediate in vivo interaction with heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), and this methyl-dependent interaction can be reversed by adjacent G9a phosphorylation. Similar phosphorylation at G2/M phase has been reported for PR-Set7 H4K20 methylase, and its catalytic function is known to play a critical role in mitosis and S phase progression (55–57).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that MLL5 is a novel substrate of Cdc2. The dynamic phosphorylation modification on MLL5 appears to control its subcellular localization and is required for mitotic entry. Our study provides a molecular basis to further explore the implication of such phosphorylation regulation on the potential histone methyltransferase activity of MLL5 in epigenetic control of the cell cycle.

This work was supported in part by BMRC-A*STAR, Singapore, Grant R-183-000-164-305, NMRC-A*STAR, Singapore, Grant R-183-000-149-213, and Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 2 Grant R-183-000-195-112.

- PHD

- plant homeodomain

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hasle H., Aricò M., Basso G., Biondi A., Cantù Rajnoldi A., Creutzig U., Fenu S., Fonatsch C., Haas O. A., Harbott J., Kardos G., Kerndrup G., Mann G., Niemeyer C. M., Ptoszkova H., Ritter J., Slater R., Starý J., Stollmann-Gibbels B., Testi A. M., van Wering E. R., Zimmermann M. (1999) Leukemia 13, 376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brezinová J., Zemanová Z., Ransdorfová S., Pavlistová L., Babická L., Housková L., Melichercíková J., Sisková M., Cermák J., Michalová K. (2007) Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 173, 10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luna-Fineman S., Shannon K. M., Lange B. J. (1995) Blood 85, 1985–1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson E. J., Scherer S. W., Osborne L., Tsui L. C., Oscier D., Mould S., Cotter F. E. (1996) Blood 87, 3579–3586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Beau M. M., Espinosa R., 3rd, Davis E. M., Eisenbart J. D., Larson R. A., Green E. D. (1996) Blood 88, 1930–1935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emerling B. M., Bonifas J., Kratz C. P., Donovan S., Taylor B. R., Green E. D., Le Beau M. M., Shannon K. M. (2002) Oncogene 21, 4849–4854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu Y., Nakamura T., Alder H., Prasad R., Canaani O., Cimino G., Croce C. M., Canaani E. (1992) Cell 71, 701–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayton P. M., Cleary M. L. (2001) Oncogene 20, 5695–5707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess J. L. (2004) Trends Mol. Med. 10, 500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu B. D., Hess J. L., Horning S. E., Brown G. A., Korsmeyer S. J. (1995) Nature 378, 505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser S., Schaft J., Lubitz S., Vintersten K., van der Hoeven F., Tufteland K. R., Aasland R., Anastassiadis K., Ang S. L., Stewart A. F. (2006) Development 133, 1423–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S., Lee D. K., Dou Y., Lee J., Lee B., Kwak E., Kong Y. Y., Lee S. K., Roeder R. G., Lee J. W. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15392–15397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuser M., Yap D. B., Leung M., de Algara T. R., Tafech A., McKinney S., Dixon J., Thresher R., Colledge B., Carlton M., Humphries R. K., Aparicio S. A. (2009) Blood 113, 1432–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madan V., Madan B., Brykczynska U., Zilbermann F., Hogeveen K., Döhner K., Döhner H., Weber O., Blum C., Rodewald H. R., Sassone-Corsi P., Peters A. H., Fehling H. J. (2009) Blood 113, 1444–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y., Wong J., Klinger M., Tran M. T., Shannon K. M., Killeen N. (2009) Blood 113, 1455–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H., Westergard T. D., Hsieh J. J. (2009) Blood 113, 1395–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellor J. (2006) Cell 126, 22–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura T., Mori T., Tada S., Krajewski W., Rozovskaia T., Wassell R., Dubois G., Mazo A., Croce C. M., Canaani E. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 1119–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milne T. A., Briggs S. D., Brock H. W., Martin M. E., Gibbs D., Allis C. D., Hess J. L. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 1107–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes C. M., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Milne T. A., Copeland T. D., Levine S. S., Lee J. C., Hayes D. N., Shanmugam K. S., Bhattacharjee A., Biondi C. A., Kay G. F., Hayward N. K., Hess J. L., Meyerson M. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoyama A., Wang Z., Wysocka J., Sanyal M., Aufiero D. J., Kitabayashi I., Herr W., Cleary M. L. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5639–5649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wysocka J., Swigut T., Milne T. A., Dou Y., Zhang X., Burlingame A. L., Roeder R. G., Brivanlou A. H., Allis C. D. (2005) Cell 121, 859–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nightingale K. P., Gendreizig S., White D. A., Bradbury C., Hollfelder F., Turner B. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4408–4416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M. G., Villa R., Trojer P., Norman J., Yan K. P., Reinberg D., Di Croce L., Shiekhattar R. (2007) Science 318, 447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebastian S., Sreenivas P., Sambasivan R., Cheedipudi S., Kandalla P., Pavlath G. K., Dhawan J. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4719–4724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujiki R., Chikanishi T., Hashiba W., Ito H., Takada I., Roeder R. G., Kitagawa H., Kato S. (2009) Nature 459, 455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambasivan R., Pavlath G. K., Dhawan J. (2008) J. Biosci. 33, 27–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda S., Chen D. Y., Westergard T. D., Fisher J. K., Rubens J. A., Sasagawa S., Kan J. T., Korsmeyer S. J., Cheng E. H., Hsieh J. J. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 2397–2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H., Cheng E. H., Hsieh J. J. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 2385–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyagi S., Chabes A. L., Wysocka J., Herr W. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Issaeva I., Zonis Y., Rozovskaia T., Orlovsky K., Croce C. M., Nakamura T., Mazo A., Eisenbach L., Canaani E. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1889–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng L. W., Chiu I., Strominger J. L. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 757–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng F., Liu J., Zhou S. H., Wang X. N., Chew J. F., Deng L. W. (2008) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2472–2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Méndez J., Stillman B. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8602–8612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochegger H., Takeda S., Hunt T. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 910–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glotzer M. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moseley J. B., Nurse P. (2009) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamashita K., Yasuda H., Pines J., Yasumoto K., Nishitani H., Ohtsubo M., Hunter T., Sugimura T., Nishimoto T. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 4331–4338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meijer L., Borgne A., Mulner O., Chong J. P., Blow J. J., Inagaki N., Inagaki M., Delcros J. G., Moulinoux J. P. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 243, 527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno S., Nurse P. (1990) Cell 61, 549–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassilev L. T., Tovar C., Chen S., Knezevic D., Zhao X., Sun H., Heimbrook D. C., Chen L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10660–10665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokoyama A., Kitabayashi I., Ayton P. M., Cleary M. L., Ohki M. (2002) Blood 100, 3710–3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reynolds J. A., Tanford C. (1970) J. Biol. Chem. 245, 5161–5165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou H., Watts J. D., Aebersold R. (2001) Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elia A. E., Cantley L. C., Yaffe M. B. (2003) Science 299, 1228–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neef R., Gruneberg U., Kopajtich R., Li X., Nigg E. A., Sillje H., Barr F. A. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunter T. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 730–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delcuve G. P., He S., Davie J. R. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 105, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito T. (2007) J. Biochem. 141, 609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Georgatos S. D., Markaki Y., Christogianni A., Politou A. S. (2009) Front. Biosci. 14, 2017–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milne T. A., Hughes C. M., Lloyd R., Yang Z., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Dou Y., Schnepp R. W., Krankel C., Livolsi V. A., Gibbs D., Hua X., Roeder R. G., Meyerson M., Hess J. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 749–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra B. P., Ansari K. I., Mandal S. S. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 1629–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kittler R., Pelletier L., Heninger A. K., Slabicki M., Theis M., Miroslaw L., Poser I., Lawo S., Grabner H., Kozak K., Wagner J., Surendranath V., Richter C., Bowen W., Jackson A. L., Habermann B., Hyman A. A., Buchholz F. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1401–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sampath S. C., Marazzi I., Yap K. L., Sampath S. C., Krutchinsky A. N., Mecklenbräuker I., Viale A., Rudensky E., Zhou M. M., Chait B. T., Tarakhovsky A. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 596–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Georgi A. B., Stukenberg P. T., Kirschner M. W. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rice J. C., Nishioka K., Sarma K., Steward R., Reinberg D., Allis C. D. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2225–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tardat M., Murr R., Herceg Z., Sardet C., Julien E. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 179, 1413–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]