Abstract

The human lysosomal enzymes α-galactosidase (α-GAL, EC 3.2.1.22) and α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (α-NAGAL, EC 3.2.1.49) share 46% amino acid sequence identity and have similar folds. The active sites of the two enzymes share 11 of 13 amino acids, differing only where they interact with the 2-position of the substrates. Using a rational protein engineering approach, we interconverted the enzymatic specificity of α- GAL and α-NAGAL. The engineered α-GAL (which we call α-GALSA) retains the antigenicity of α-GAL but has acquired the enzymatic specificity of α-NAGAL. Conversely, the engineered α-NAGAL (which we call α-NAGALEL) retains the antigenicity of α-NAGAL but has acquired the enzymatic specificity of the α-GAL enzyme. Comparison of the crystal structures of the designed enzyme α-GALSA to the wild-type enzymes shows that active sites of α-GALSA and α-NAGAL superimpose well, indicating success of the rational design. The designed enzymes might be useful as non-immunogenic alternatives in enzyme replacement therapy for treatment of lysosomal storage disorders such as Fabry disease.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Complex, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Carbohydrate Processing, Enzyme Structure, Glycoprotein, Glycoprotein Structure, Lysosomal Glycoproteins, Lysosomal Storage Disease, X-ray Crystallography

Introduction

Lysosomal enzymes are responsible for the catabolism of metabolic products in the cell. Deficiencies in lysosomal enzymes lead to lysosomal storage diseases, characterized by an accumulation of undegraded substrates in the lysosome. In humans, there are at least 40 different lysosomal storage diseases (including, for example, Tay-Sachs, Sandhoff, Gaucher, and Fabry diseases), each of which is caused by a lack of a specific enzymatic activity. Fabry disease is caused by a defect in the GLA gene, leading to loss of activity in the enzyme α-galactosidase (α-GAL,3 EC 3.2.1.22, also known as α-GAL A)(1). The α-GAL enzyme cleaves substrates containing terminal α-galactosides, including glycoproteins, glycolipids, and polysaccharides. Defects in the GLA gene in Fabry patients lead to the accumulation of unprocessed neutral substrates (primarily globotriaosylceramide (Gb3)), which then leads to the progressive deterioration of multiple organ systems and premature death. Fabry disease is an X-linked inherited disorder with an estimated prevalence of ∼1 in 40,000 male births but may be highly underdiagnosed (1, 2).

The human gene most closely related to the GLA gene is the NAGA gene, encoding the enzyme α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (α-NAGAL, EC 3.2.1.49, also known as NAGA and α-GAL B) (3). The two genes are derived from a common ancestor (4), encoding proteins that share 46% amino acid sequence identity (Fig. 1A); they belong to glycoside hydrolase family 27 and clan D (5). The α-NAGAL enzyme recognizes and cleaves substrates containing terminal α-N-acetylgalactosaminide (α-GalNAc) sugars, and (less efficiently) substrates containing terminal α-galactosides. Defects in the NAGA gene lead to the lysosomal storage disease Schindler disease, characterized by the accumulation of glycolipids and glycopeptides, resulting in a wide range of symptoms, including neurological, skin, and cardiac anomalies (3).

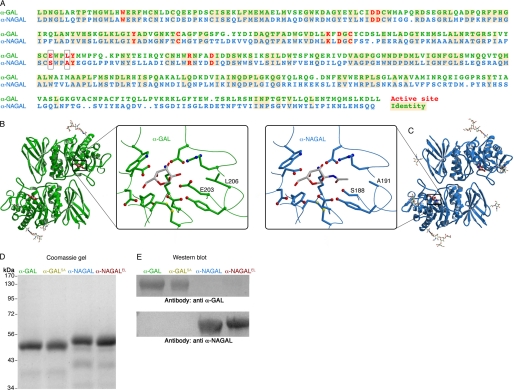

FIGURE 1.

α-GAL and α-NAGAL structural and biochemical analyses. A, sequence alignment of the α-GAL and α-NAGAL proteins. Active site residues are red, and identities have yellow backgrounds. The two active site residues that differ are boxed. B and C, ribbon diagrams of α-GAL (green) and α-NAGAL (cyan) with attached carbohydrates. Insets show the active sites of α-GAL and α-NAGAL with their catalytic products α-galactose and α-GalNAc, respectively (gray). 11 of the 13 active site residues are conserved between the enzymes, although the overall sequence identity is 46%. The two residues that differ (Glu-203 and Leu-206 in α-GAL; Ser-188 and Ala-191 in α-NAGAL) select for the substituent on the 2-position of the ligand. D, the four purified proteins are shown on a Coomassie-stained SDS gel. α-GAL and α-GALSA (with three N-linked glycosylation sites each) run smaller on the SDS gel than α-NAGAL and α-NAGALEL (with five N-linked glycosylation sites each). E, Western blots of the four proteins, detected with polyclonal anti-α-GAL (top) and polyclonal anti-α-NAGAL antibodies (bottom). The variant proteins retain the antigenicity of the original proteins.

The only approved therapy for the treatment of Fabry disease is enzyme replacement therapy, where patients are injected with recombinant enzyme purified from mammalian cell expression systems (6, 7). One problem with this treatment is that up to 88% of patients develop IgG antibodies against the injected recombinant enzyme (6, 8). In patients who make no functional α-GAL enzyme, the recombinant α-GAL used in enzyme replacement therapy can be treated as a foreign antigen. Because the GLA gene is located on the X-chromosome, hemizygous males who inherit a non-functional copy of the gene have no second copy to establish immunotolerance.

Previously, we determined the three-dimensional crystallographic structures of the human α-GAL and α-NAGAL enzymes (9, 10). As expected for two structures that share 46% sequence identity, the overall folds of the two enzymes are similar (Fig. 1, B and C). Each enzyme is a dimer where each monomer contains an N-terminal (β/α)8 barrel with the active site and a C-terminal antiparallel β domain. The monomers of the two enzymes superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 0.90 Å for 378 α carbons. The active sites of the two structures are highly similar, as 11 of the 13 active site residues are conserved. The only differences in the active sites of the two structures correspond to where the substrates are different: in α-GAL, the residues near the 2-OH on the substrate include larger glutamate and leucine, whereas in α-NAGAL, the larger 2-N-acetyl on the substrate interacts with the smaller serine and alanine residues on the enzyme (Fig. 1, B and C). As we and others have noted, in glycoside hydrolase family 27, the two residues primarily responsible for recognition of the 2-position of the ligand are both located on the same loop in the structure, the β5–α5 loop in the (β/α)8 barrel domain (9–13).

The similarities between the active sites of the enzymes in the family and the proximity of the two residues responsible for the recognition of the 2-position of the ligand led us and others to hypothesize that interconversion of the enzyme specificities would be possible (9, 14). We replaced two residues in the active site of α-GAL (E203S and L206A), leading to a new protein (α-GALSA) with the enzymatic specificity of an α-NAGAL enzyme. Additionally, we replaced two residues in the active site of α-NAGAL (S188E and A191L), leading to a new protein (α-NAGALEL) with the enzymatic specificity of an α-GAL enzyme. In this report, we show that the designed enzymes maintain the antigenicity of the original protein, but have the specificity of the other enzyme. X-ray crystallographic studies of the α-GALSA protein provide a structural basis for ligand specificity in the family of proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

Human α-GAL and human α-NAGAL were expressed in stably transfected Trichoplusia ni (Tn5) insect cells as described previously (10, 15). The α-GALSA variant was generated from the wild-type α-GAL construct using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (forward primer, 5′-G TAC TCC TGT TCG TGG CCT GCT TAT ATG TGG-3′ (substitutions in bold), and reverse primer, 5′-CAC AAT GCT TCT GCC AGT CCT ATT CAG GGC-3′), ligated, transformed into bacteria, and confirmed by sequencing. The α-NAGALEL variant was derived from the wild-type α-NAGAL construct by PCR (forward primer, 5′-CGG CCT CCC CCC AAG GGT GAA CTA-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-CC TTC ATA GAG TGG CCA CTC GCA GGA GAA-3′), ligated, transformed into bacteria, and sequenced.

Cell Transfection

Adherent Tn5 cells in SFX-Insect medium (HyClone) were transfected with plasmid DNA, and selection for stably transfected cells using 100 μg/ml blasticidin (added after 48 h and every 48 h for 10 days) was carried out. Stable adherent cells were re-suspended in SFX medium for larger scale suspension cultures.

Protein Expression and Purification

One-liter cultures of stable cells secreting α-GALSA and α-NAGALEL proteins were grown to 3 × 106 cells/ml. The supernatant was clarified and concentrated by tangential flow filtration (Millipore Prep/Scale) and exchanged into Ni2+ binding buffer (50 mm Na3PO4, pH 7.0, 250 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, and 0.01% NaN3). The retentate was loaded onto a Ni2+-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column (Amersham Biosciences) and eluted with a gradient of 0–60% elution buffer (50 mm Na3PO4, pH 7.0, 250 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, and 0.01% NaN3). Eluate fractions were pooled, desalted, and concentrated before loading onto a Source 15Q anion-exchange column (10). Fractions eluted by a linear salt gradient were screened by activity assays and by Western blots. Fractions containing pure protein were pooled and concentrated to 1.0 mg/ml for storage.

Kinetic Assays

Hydrolysis of the synthetic substrates para-nitrophenyl-α-galactose (pNP-α-Gal) and para-nitrophenyl-α-N-acetylgalactosamine (pNP-α-GalNAc) (Toronto Research Chemicals) at 37 °C were monitored by absorbance at 400 nm using an extinction coefficient of 18.1 mm−1 cm−1. 0.25–1.2 μg of enzyme in 10 μl of 100 mm citrate/phosphate buffer (pH 4.5) was added to 12 substrate concentrations (pNP-α-Gal from 0.1 to 50 mm, and pNP-α-GalNAc from 0.01 to 10 mm). Each minute for 10 min, the sample absorbance was measured after adding 200 mm Na3BO3 buffer, pH 9.8. Error bars were determined from triplicate measurements by two experimenters for each data point. Km, Vmax, kcat, and error bars were determined from a weighted fit of Michaelis-Menten hyperbola in KaleidaGraph. Substrate solubility limits prevented saturation in some experiments. Substrate specificity ratios for each enzyme were defined as (kcat/Km)pNP-α-GalNAc/(kcat/Km)pNP-α-Gal, indicating the preference of an enzyme for galactosaminide substrates.

Crystallization and X-ray Data Collection

Crystals of α-GALSA were grown as described for the D170A α-GAL variant (15). Crystals were obtained from a 1:1 mixture of reservoir solution (12% polyethylene glycol 8,000, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, and 22 mm Mg(CH3COO)2) and 7.0 mg/ml protein in 10 mm Na3PO4, pH 6.5. Crystals were transferred stepwise into reservoir solution containing 200 mm ligand (GalNAc or galactose) and then into cryoprotectant solution (15% polyethylene glycol 8,000, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 22 mm Mg(CH3COO)2, 20% glycerol, and 200 mm ligand). Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen, and x-ray data were collected at 100 K at beamline X6A at the Brookhaven National Laboratory or at the microfocus beamline NECAT 24-ID-C at Argonne National Laboratory. X-ray images were processed using HKL2000 (16) and phased by molecular replacement in AMoRe (17) or by Fourier synthesis using human α-GAL coordinates (PDB: 3HG3) (15). We selected the overall resolution limits based upon I/σI criteria. Atomic models were built using the program O (18), with refinement in REFMAC5 (17). Ramachandran plots were computed using PROCHECK (19). Coordinates were superimposed using LSQMAN (20). Figures were made in MolScript (21) and POVScript+ (22). Coordinates and structure factors are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 3LX9, 3LXA, 3LXB, and 3LXC.

RESULTS

Biochemical Characterization

We expressed the four enzymes (α-GAL, α-GALSA, α-NAGAL, and α-NAGALEL) in stably transfected Tn5 insect cells and purified protein from the supernatant. SDS-PAGE analysis shows that the purified variant proteins migrate at the same size as their wild-type equivalents, ∼50 kDa for α-GAL and α-GALSA and 52 kDa for α-NAGAL and α-NAGALEL (Fig. 1D). To test the antigenicity of the wild-type and variant proteins, we performed Western blots on all four proteins using antibodies against human α-GAL and human α-NAGAL. α-GAL and α-GALSA cross-react only with the anti-α-GAL antibody, whereas α-NAGAL and α-NAGALEL cross-react only with the anti-α-NAGAL antibody (Fig. 1E), indicating that the variant proteins retain their original antigenicity.

Enzymatic Activity

We tested the four enzymes against two synthetic substrates, pNP-α-Gal and pNP-α-GalNAc. In the wild-type enzymes, the larger active site of α-NAGAL allows it to bind and cleave both substrates, although the pNP-α-Gal less efficiently. The smaller active site of α-GAL allows for efficient catalysis of pNP-α-Gal, but no detectable activity on pNP-α-GalNAc due to steric clashes between the N-acetyl group on the 2-position of the sugar and the larger Glu-203 and Leu-206 side chains of α-GAL. Table 1 summarizes the enzyme kinetic data.

TABLE 1.

Enzymatic parameters

| Enzyme | pNP-α-Gal |

pNP-α-GalNAc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km | kcat | kcat/Km | Km | kcat | kcat/Km | |

| mm | s−1 | mm−1s−1 | mm | s−1 | mm−1s−1 | |

| α-GAL | 6.88 ± 0.07 | 37.8 ± 0.2 | 5.49 ± 0.06 | No activity detecteda | ||

| α-NAGALEL | 7.58 ± 0.07 | 13.7 ± 0.1 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | No activity detecteda | ||

| α-NAGAL | 27.5 ± 4.7 | 10.7 ± 0.9 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 22.4 ± 0.1 |

| α-GALSA | 49.1 ± 7.2 | 1.20 ± 0.14 | 0.024 ± 0.005 | 21.0 ± 0.8 | 21.5 ± 0.7 | 1.03 ± 0.03 |

a kcat < 0.01 s−1.

The variant enzymes α-GALSA and α-NAGALEL show the opposite substrate specificity compared with their starting wild-type enzymes. The α-NAGALEL enzyme shows the catalytic properties of wild-type α-GAL: it has no activity against the pNP-α-GalNAc substrate, but shows high activity against pNP-α-Gal. The α-GALSA enzyme has the catalytic properties of wild-type α-NAGAL: it has activity against pNP-α-GalNAc and reduced activity against pNP-α-Gal.

Because the enzymes in this family have overlapping substrate specificity, we used the ratio of the specificity constant kcat/Km for the two substrates as a measure of the ability of the enzymes to discriminate between the two related substrates. The substrate specificity ratios (kcat/Km)pNP-α-GalNAc/(kcat/Km)pNP-α-Gal for α-GAL and α-NAGALEL are zero, because those enzymes show no activity toward the pNP-α-GalNAc substrate. The substrate specificity ratios for α-NAGAL and α-GALSA are similar: 57.3 ± 10.3 for α-NAGAL and 42.9 ± 9.0 for α-GALSA, showing they have comparable ability to distinguish between the two substrates.

Comparison of the enzymatic parameters of α-GAL and of α-NAGALEL (the enzyme engineered to have α-galactosidase activity) shows that the Km values of the two enzymes are similar (6.9 and 7.6 mm, respectively, for the pNP-α-Gal substrate). The engineered enzyme has a turnover number kcat that is ∼one-third that of the native α-GAL enzyme (13.7 s−1 versus 37.8 s−1, respectively).

Comparison of the enzymatic parameters of α-NAGAL and of α-GALSA reveals that the Km value of the engineered enzyme against the pNP-α-GalNAc substrate is 30-fold larger than that of the wild-type enzyme (21.0 and 0.68 mm, respectively) and 2-fold larger against the pNP-α-Gal substrate (49.1 and 27.5 mm, respectively). The turnover numbers kcat of α-NAGAL and α-GALSA are similar against the pNP-α-GalNAc substrate (15.1 and 21.5 s−1, respectively) and differ 9-fold against the pNP-α-Gal substrate (10.7 versus 1.2 s−1).

Overall the kinetic parameters show that, although the engineered enzymes are not as efficient as their wild-type counterparts, they have the same ability to discriminate among different substrates as their wild-type equivalents. In particular, the α-GALSA-engineered enzyme is somewhat less effective at catalyzing the turnover of substrate compared with its wild-type equivalent, α-NAGAL.

Crystal Structures

To examine the structural basis for the reduced catalytic efficiency of the α-GALSA enzyme, we determined four crystal structures of α-GALSA in complex with three different ligands, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), galactose, and glycerol (Table 2 and Fig. 2, A–C). Superposition of α-GALSA and α-NAGAL by their (β/α)8 barrel domains results in an r.m.s.d. of 0.58 Å for 290 Cα atoms in the domain. Remarkably, the superposition of the entire (β/α)8 domains shows that the GalNAc ligands and the active site residues superimpose nearly exactly (Fig. 2D). Although 54% of the residues differ between α-NAGAL and α-GALSA, the ligands superimpose with an r.m.s.d. of 0.38 Å for the 15 atoms in the ligand.

TABLE 2.

α-GALSA data collection and refinement statistics

| Ligand |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GalNAc | Galactose | Glycerol | Glycerol | |

| PDB ID | 3LX9 | 3LXA | 3LXB | 3LXC |

| Data collection | ||||

| Beamline | APS 24-ID-C | NSLS X6A | NSLS X6A | APS 24-ID-C |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07188 | 0.98010 | 0.98010 | 1.07188 |

| Space group | C2221 | P212121 | P212121 | C2221 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50-2.05 | 50-3.0 | 50-2.85 | 50-2.35 |

| (last shell) | (2.09-2.05) | (3.11-3.0) | (2.90-2.85) | (2.39-2.35) |

| Cell parameters | 89.95, 139.49, 182.58 | 59.50, 105.85, 181.85 | 59.57, 106.92, 181.51 | 89.75, 139.77, 182.45 |

| a, b, c (Å) | ||||

| No. of observations | 481,042 | 172,299 | 136,330 | 193,566 |

| No. of unique observations | 72,009 | 23,638 | 27,897 | 47,535 |

| (last shell) | (3,354) | (2,309) | (1,334) | (2,335) |

| Multiplicity | 6.7 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 4.1 |

| (last shell) | (3.6) | (7.2) | (4.9) | (4.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.4 | 100.0 | 99.3 | 98.6 |

| (last shell) | (93.3) | (99.9) | (99.9) | (98.7) |

| Rsyma | 0.120 | 0.271 | 0.177 | 0.153 |

| (last shell) | (0.701) | (0.851) | (0.616) | (0.862) |

| I/σI | 18.6 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 12.3 |

| (last shell) | (1.6) | (1.8) | (2.2) | (2.0) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Rwork/Rfreeb (%) | 17.62/21.82 | 21.45/24.39 | 22.50/26.38 | 18.35/23.68 |

| No. of atoms | 7,057 | 6,557 | 6,657 | 7,032 |

| Protein | 6,241 | 6,303 | 6,320 | 6,241 |

| Carbohydrate | 257 | 218 | 170 | 227 |

| Water | 559 | 36 | 131 | 552 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 36 | 12 |

| Average B, Å2 | 37.5 | 34.5 | 32.5 | 45.3 |

| Protein average B, Å2 | 36.3 | 33.9 | 31.8 | 44.4 |

| Ramachandran plotc | ||||

| Favored (%) | 91.4 | 89.5 | 89.5 | 89.7 |

| Allowed (%) | 8.0 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.5 |

| Generous (%) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Forbidden (%) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| r.m.s.d. | ||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0053 | 0.0150 | 0.0088 | 0.0081 |

| Angles (°) | 1.056 | 1.502 | 1.222 | 1.172 |

a Rsym = ΣhΣi|Ih,i − 〈Ih〉|/ΣhΣi|Ih,i|, where Ih,i is the ith intensity measurement of reflection h and 〈Ih〉 is the average intensity of that reflection.

b Rwork/Rfree = Σh|FP − FC|/Σh|FP|, where FC is the calculated and FP is the observed structure factor amplitude of reflection h for the working or free set, respectively.

c Ramachandran statistics were calculated in PROCHECK.

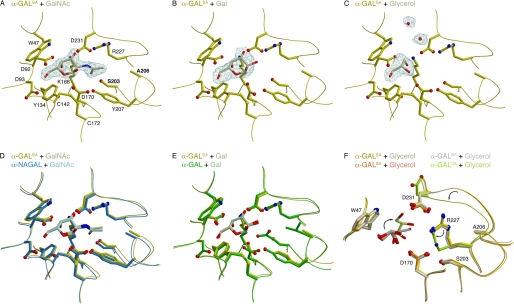

FIGURE 2.

α-GALSA crystal structures. A–C, σA-weighted 2Fo − Fc total omit electron density maps of α-GALSA calculated in SFCHECK (17). A, GalNAc-soaked crystal contoured at 2.0σ. B, galactose-soaked crystal contoured at 1.8σ. C, glycerol-soaked crystal soaked at 1.0σ. Maps have a cover radius drawn around ligands and/or waters in the active site. Active site residues are labeled in A. D, a superposition of crystal structures of the active sites of α-GALSA and α-NAGAL, each with α-GalNAc bound in the active site. When the structures are superimposed by their (β/α)8 barrels, the ligands superimpose nearly exactly. E, a superposition of crystal structures of the active sites of α-GALSA and α-GAL, each with α-galactose bound in the active site. F, a superposition of the four monomers of glycerol-soaked α-GALSA, with glycerol bound in the active site. In one of the four structures (green), the glycerol binds in a vertical orientation, and shows differences in Arg-227 and the loop containing Asp-231 (arrows).

Superposition of the (β/α)8 barrel domains of α-GALSA and α-GAL shows that the active site residues and ligands superimpose closely, except for Glu-203 and Leu-206 in α-GAL, which are replaced with Ser and Ala in α-GALSA (Fig. 2E). The structure of α-GALSA with galactose bound shows a shift in the location of the catalytic nucleophile Asp-170 relative to its location in other structures in the family. The Asp-170 nucleophile shifts into the empty space produced by the reduction in size of the side chain in the E203S substitution. This shift affects the hydrogen bonding of Asp-170 to Tyr-134 and Tyr-207, and likely contributes to the reduced catalytic efficiency of the α-GALSA variant protein.

The crystallographic experiments used the cryoprotectant glycerol, which appeared in the active site of α-GALSA. We determined two structures of glycerol-soaked α-GALSA in space groups C2221 and P212121. Because each crystal has two monomers of the protein in the asymmetric unit, we have four crystallographically independent active site complexes with glycerol. One of the four glycerol-soaked monomers shows significant changes in the active site: the glycerol binds in a different orientation, the Arg-227 side-chain rotamer changes, and the β6–α6 loop containing the catalytic acid/base Asp-231 shifts as well (Fig. 2F). This large rearrangement in the active site is unique to α-GALSA among the glycosidase family 27 structures and may also contribute to the reduced catalytic efficiency of α-GALSA.

DISCUSSION

The active site of human α-GAL is unable to accommodate 2-N-acetylated ligands due to steric clashes between the protein and the N-acetyl group on the ligand. Here, we have engineered α-GALSA, the first α-GAL enzyme capable of binding α-GalNAc ligands. In the reciprocal experiment, the engineered α-NAGALEL enzyme has lost all of its activity against α-GalNAc ligands and has enhanced activity against α-galactosides.

Enzyme Replacement Therapy

Enzyme replacement therapy can successfully treat Fabry disease. However, up to 88% of male patients develop an immune response to the injected recombinant enzyme, including both IgG- and IgE-based reactions (6, 8, 23). The antigenicity of the glycoproteins used in enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease patients might limit the effectiveness of the treatment by reducing the amount of enzyme effectively delivered to the lysosomes. We envision the α-NAGALEL molecule would have little immunogenicity in Fabry disease patients (who make typical amounts α-NAGAL glycoprotein and are thus immunologically tolerant toward α-NAGAL). Consistent with this, heterozygous female Fabry disease patients (with one wild-type copy of the GLA gene) do not make the comparable immune responses as their hemizygous male counterparts against injected enzyme during enzyme replacement therapy (24, 25).

Although patients with the severe form of Fabry disease have little or no α-GAL enzyme activity, patients with the variant forms of Fabry disease can have from 5 to 35% of wild-type enzyme activity (26, 27). This suggests that the threshold level of α-GAL enzymatic activity necessary to prevent Fabry disease symptoms is <100% wild-type activity. Although the enzymatic activity of the engineered proteins is lower than their wild-type equivalents, in enzyme replacement therapy, the reduced immunogenicity of the designed proteins might compensate for their reduced activity.

Sakuraba and colleagues have also tested this hypothesis by reporting a protein similar in design to α-NAGALEL, but expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells, leading to a different glycosylation pattern (14). When injected in a mouse model of Fabry disease, the mammalian-expressed protein led to a reduction in the amount of Gb3 in the tissues of the mouse. This further suggests that the designed enzyme might act as a useful tool for the treatment of Fabry disease.

Properties of the Engineered Enzymes

Western blotting with anti-α-GAL and anti-α-NAGAL antibodies shows that the former reacts only with α-GAL and α-GALSA, whereas the latter reacts only with α-NAGAL and α-NAGALEL. The sequence divergence between α-GAL and α-NAGAL is sufficient to show no immunological cross-reactivity. Thus, engineering the active sites of α-GAL and α-NAGAL to have novel substrate specificities leads to new enzyme activities without altering antigenicity. This approach may be useful as a general strategy for protein-based therapeutics where reducing immunogenicity is an issue, such as Gaucher disease, where 15% of patients on enzyme replacement therapy develop IgG antibodies to the recombinant enzyme (28).

The diverse sequences in glycoside hydrolase family 27 (which includes human α-GAL and α-NAGAL) show high conservation of the active site residues, indicating strong evolutionary pressure on the active site. One modular component of ligand binding in the family is the recognition of the 2-position of the sugar ring. In this family, a single loop on the protein, the β5–α5 loop in the N-terminal domain, interacts with the substituent on the 2-position of the sugar. The similarity across the members of the family allowed us to interconvert the ligand recognition through substitution of two residues in the loop. The modularity of the loop is also seen in the structures of other members of the family, including the rice and Hypocrea jecorina α-GAL structures, where one turn of helix in the β5–α5 loop is replaced with a shorter loop and a longer β5 strand (12, 29). In those structures, Cys and Trp residues fill the space of the Glu-203 and Leu-206 residue of α-GAL or the Ser-188 and Ala-191 residues in α-NAGAL.

The newly engineered enzymes α-GALSA and α-NAGALEL are not as catalytically efficient as their wild-type equivalents. The structures of α-GALSA suggest that there is considerably more flexibility in the active site of the α-GALSA enzyme when compared with α-NAGAL, the enzyme with an identical active site constellation.

The glycerol-soaked structures of α-GALSA provide a structural explanation for the reduced catalytic efficiency of the engineered enzyme. When the larger Glu-203 and Leu-206 residues of α-GAL are replaced with smaller Ser and Ala residues in α-GALSA, the active site has more open space in it. This allows the Arg-227 side chain to move toward the space vacated by the shortening of the Glu-203 side chain, and the β6–α6 loop containing Asp-231 moves toward the space vacated by the shortening of the Leu-206 side chain. The crystal structures indicate that the active site of α-GALSA is more dynamic than the active sites of the wild-type enzymes α-GAL and α-NAGAL, which might explain the reduced catalytic efficiency of the designed α-GALSA enzyme. Another indication of the higher mobility of the active site of α-GALSA appears in the glycerol-soaked α-GALSA structure, which has higher atomic B-factors in the rearranged β6–α6 loop.

In this report, we describe the first instance of bidirectional interconversion of the enzymatic activities of two human lysosomal enzymes. Rational design of enzymatic function is a challenging task and generally requires large changes in the active site: for example, the classic case of conversion of trypsin activity into that of chymotrypsin required 11 substitutions in 4 sites on the protein (30). In general, changing substrate specificity is easier than changing the reaction mechanism of an enzyme (31). The family of lysosomal glycosidases might prove to be a fruitful target for further enzyme engineering, because many glycosidases use a similar mechanism with an arrangement of two carboxylates located on opposite sides of the glycosidic linkage to be cleaved.

In conclusion, we have shown the viability of a rational design approach to engineering new functionality into human lysosomal enzymes. This approach allows for encoding new enzymatic functions into existing protein scaffolds. By reusing existing proteins in new ways, our approach avoids the immunogenicity problems that are frequently seen in enzyme replacement therapies. This approach might also be used for a wide range of protein-based therapeutics when immunogenicity problems exist.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Jean Jankonic, Marc Allaire, and Vivian Stojanoff at the National Synchrotron Light Source X6A beam line. We thank Igor Kourinov and the staff of the Advanced Photon Source Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK76877 (to S. C. G.). This work was also supported by National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship 0654128 (to N. E. C.). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3LX9, 3LXA, 3LXB, and 3LXC) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- α-GAL

- α-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.22)

- α-NAGAL

- α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (EC 3.2.1.49)

- Gb3

- globotriaosylceramide

- pNP-α-Gal

- para-nitrophenyl-α-galactose

- pNP-α-GalNAc

- para-nitrophenyl-α-N-acetylgalactosamine

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desnick R. J., Ioannou Y. A., Eng C. M. (2001) in The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (Scriver C. R., Beaudet A. L., Sly W. S., Valle D. eds) 8th Ed., pp. 3733–3774, McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spada M., Pagliardini S., Yasuda M., Tukel T., Thiagarajan G., Sakuraba H., Ponzone A., Desnick R. J. (2006) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desnick R. J., Schindler D. (2001) in The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (Scriver C. R., Beaudet A. L., Sly W. S., Valle D. eds) 8th Ed., pp. 3483–3505, McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang A. M., Bishop D. F., Desnick R. J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 21859–21866 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eng C. M., Guffon N., Wilcox W. R., Germain D. P., Lee P., Waldek S., Caplan L., Linthorst G. E., Desnick R. J. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiffmann R., Kopp J. B., Austin H. A., 3rd, Sabnis S., Moore D. F., Weibel T., Balow J. E., Brady R. O. (2001) JAMA 285, 2743–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffmann R., Ries M., Timmons M., Flaherty J. T., Brady R. O. (2006) Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21, 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garman S. C., Garboczi D. N. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 319–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark N. E., Garman S. C. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 393, 435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garman S. C., Hannick L., Zhu A., Garboczi D. N. (2002) Structure 10, 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto Z., Kaneko S., Momma M., Kobayashi H., Mizuno H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20313–20318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garman S. C. (2006) Biocat. Biotrans. 24, 129–136 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajima Y., Kawashima I., Tsukimura T., Sugawara K., Kuroda M., Suzuki T., Togawa T., Chiba Y., Jigami Y., Ohno K., Fukushige T., Kanekura T., Itoh K., Ohashi T., Sakuraba H. (2009) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85, 569–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guce A. I., Clark N. E., Salgado E. N., Ivanen D. R., Kulminskaya A. A., Brumer H., 3rd, Garman S. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3625–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) in Methods in Enzymology: Macromolecular Crystallography, part A (Carter C. W., Sweet R. M. eds) pp. 307–326, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collaborative Computational Project, N. (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D50, 760–763 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laskowski R. A., Macarthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleywegt G. J., Read R. J. (1997) Structure 5, 1557–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraulis P. J. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 946–950 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenn T. D., Ringe D., Petsko G. A. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 944–947 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodensteiner D., Scott C. R., Sims K. B., Shepherd G. M., Cintron R. D., Germain D. P. (2008) Genet. Med. 10, 353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vedder A. C., Breunig F., Donker-Koopman W. E., Mills K., Young E., Winchester B., Ten Berge I. J., Groener J. E., Aerts J. M., Wanner C., Hollak C. E. (2008) Mol. Genet. Metab. 94, 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bénichou B., Goyal S., Sung C., Norfleet A. M., O'Brien F. (2009) Mol. Genet. Metab. 96, 4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayes J. S., Scheerer J. B., Sifers R. N., Donaldson M. L. (1981) Clin. Chim. Acta 112, 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ries M., Gupta S., Moore D. F., Sachdev V., Quirk J. M., Murray G. J., Rosing D. R., Robinson C., Schaefer E., Gal A., Dambrosia J. M., Garman S. C., Brady R. O., Schiffmann R. (2005) Pediatrics 115, e344–e355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starzyk K., Richards S., Yee J., Smith S. E., Kingma W. (2007) Mol. Genet. Metab. 90, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golubev A. M., Nagem R. A., Brandão Neto J. R., Neustroev K. N., Eneyskaya E. V., Kulminskaya A. A., Shabalin K. A., Savel'ev A. N., Polikarpov I. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 339, 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perona J. J., Hedstrom L., Rutter W. J., Fletterick R. J. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 1489–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toscano M. D., Woycechowsky K. J., Hilvert D. (2007) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46, 3212–3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]