Abstract

Hypoxia-induced gene expression is a critical determinant of neuron survival after stroke. Understanding the cell autonomous genetic program controlling adaptive and pathological transcription could have important therapeutic implications. To identify the factors that modulate delayed neuronal apoptosis after hypoxic injury, we developed an in vitro culture model that recapitulates these divergent responses and characterized the sequence of gene expression changes using microarrays. Hypoxia induced a disproportionate number of bZIP transcription factors and related targets involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Although the temporal and spatial aspects of ATF4 expression correlated with neuron loss, our results did not support the anticipated pathological role for delayed CHOP expression. Rather, CHOP deletion enhanced neuronal susceptibility to both hypoxic and thapsigargin-mediated injury and attenuated brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced neuroprotection. Also, enforced expression of CHOP prior to the onset of hypoxia protected wild-type cultures against subsequent injury. Collectively, these findings indicate CHOP serves a more complex role in the neuronal response to hypoxic stress with involvement in both ischemic preconditioning and delayed neuroprotection.

Keywords: Apoptosis, ER Stress, Gene Expression, Hypoxia, Neuron

Introduction

Although neuronal necrosis remains an important target for stroke therapeutics, delayed apoptosis and other genetically based cell death-signaling programs figure prominently in several forms of this disease (1). In contrast to the rapid time-course characteristic of neuronal necrosis, programmed cell death, triggered under conditions of both transient focal and global ischemia, exhibits delayed kinetics making it a tractable drug target (2, 3). In humans, magnetic resonance imaging data has revealed that cell death in the ischemic penumbra and other vulnerable regions continues long after the initial insult (4). Data indicating that macromolecular synthesis inhibitors are protective in such paradigms support a pathological role for de novo gene expression (5, 6). However, although stroke studies performed using genetically manipulated mice have identified a range of putative therapeutic targets involved in delayed cell death (7), our understanding regarding the proximate transcriptional responses driving adaptive and pathological gene expression and the factors that determine the balance between these opposing programs remains incomplete.

In contrast to the extensive pattern of necrotic cell death induced after stroke, even relatively mild ischemia can exert changes in brain function ranging from reversible changes in synaptic function to selective neuron loss (8). Particularly sensitive brain structures include CA1 hippocampal neurons, pyramidal neurons in layers III and V of the cortex, and reticular neurons within the thalamus (9, 10). Not surprisingly, this pattern of injury correlates with deficits in memory, arousal, and coordination observed after cardiac arrest (11). The fact that selective neuron vulnerability can also be recapitulated in vitro indicates that this death program may be cell autonomous. A popular explanation regarding the molecular basis for this response involves differences in the relative stoichiometry of the wide variety of glutamate receptors, calcium-binding proteins, and Bcl-2-related proteins expressed in the brain (12). It is also clear that intrinsic differences in balance between survival and cell death transcripts and their gene products induced during the peri-ischemic period play a role. However, even in particularly ischemia-sensitive cell populations, de novo transcription can also promote ischemic tolerance through the regulated expression of neuroprotective factors, including erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor (13).

In the current study we used expression microarrays to study the genetic mechanisms regulating this transition from adaptive to pathological transition in hypoxic dissociated neuronal cultures. In addition to characterizing the temporal sequence of hypoxia-induced transcriptional responses, we discovered that, in contrast to ATF4, native expression of the related bZIP heterodimeric factor CHOP-10 was not predictive of in vitro neuron loss as expected from prior published observations. In fact, enforced expression of CHOP protected neurons against hypoxic injury. In addition to being potently induced by the neurotrophin BDNF,2 CHOP was required for BDNF-mediated protection. These data indicate in the neuronal response to hypoxia CHOP-10 plays a supportive and more complex role than previously appreciated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Hoechst 33342, polyethyleneimine, sodium borate, protease inhibitor mixture (P1754), DMSO, actinomycin D, cycloheximide, the sesquiterpene lactone thapsigargin, and l-glutamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Glutamic acid was purchased from RBI, Inc. (Natick, MA). Cell culture grade 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, Neurobasal® media and B27 (antioxidant-plus) supplement were purchased from Invitrogen. BDNF was obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). HEK293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and passaged in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/10% fetal calf serum. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Primary Neuronal Cultures

Culture surfaces were pretreated overnight with filter sterilized polyethyleneimine diluted 1:500 in sodium borate buffer (150 mm, pH 8.0) and washed three times with sterile ddH20 before use. All protocols were approved by the University of Rochester committee on animal resources, and complied with relevant federal guidelines. B6.129S-Ddit3tm1Dron/J chop-10 knock-out mice backcrossed to the c57BL/6J background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Cortical neuronal cultures were established from timed pregnant wild-type and chop−/− E15.5 mice using the Neurobasal/B27 media formulation. Briefly, corticies were dissected free of meninges, transferred to chilled Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline; Ca2+/Mg2+-free), and incubated in 0.25% trypsin (1 ml/hemisphere) for 15 min at room temperature. Trypsin was removed by rinsing three times with minimal essential medium, and the tissue was triturated in plating media (Neurobasal media, 1× B27 supplement, 25 mm glutamic acid, 100 mm glutamate) and seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells on 12-mm coverslips (Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) or in 60-mm tissue culture plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY) at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/well.

Cell Death Assays

Cultures maintained under ambient oxygen conditions were exposed to hypoxia (0.3–0.5% O2) in Neurobasal/B27 media (25 mm glucose) using a triple gas cell culture incubator (CB150, Binder, Tuttlingen, German). Samples were not reperfused prior to analysis unless indicated. To assess nuclear morphology cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min at room temperature, counterstained with 5 μm Hoechst 33342, and mounted in Mowiol. Nuclear pyknosis was assessed in triplicate wells by counting five to six non-overlapping fields per coverslip. Data are presented as the % pyknosis (average ± S.D.). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H- tetrazolium (MTS) assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI) in 96-well dishes with primary tissue plated at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well in a volume of 100 μl. Following either drug or hypoxia exposure, plates were returned to normoxic conditions and treated with the MTS reagent, incubated for 2 h, and analyzed on a Spectramax M5e absorbance plate reader at 492 nm (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Data represent viability relative to untreated controls.

Microarray Sample Preparation and Hybridization

Total RNA from cortical cultures was harvested using the RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen) from paired 60-mm dishes. Total RNA yield (average ± S.D.) was analyzed (0 h, 28.2 ± 4.5 mg; 3 h, 29.6 ± 5.7 mg; 12 h, 20.3 ± 2.9 mg; and 18 h, 25.0 ± 4.2 mg), and RNA integrity was confirmed by gel electrophoresis. For cDNA synthesis reactions, 10 μg of total RNA from each sample was modified at the 3′-end to contain an initiation site for T7 RNA polymerase. In vitro transcription with biotinylated UTP and CTP was carried out using 1 μg of the cDNA product. Twenty micrograms of full-length cRNA was fragmented in 200 mm Tris-acetate (pH 8.1), 500 mm KOAc, and 150 mm MgOAc at 94 °C for 35 min and analyzed by gel electrophoresis to confirm the appropriate size distribution prior to hybridization. Hybridization was performed using the Affymetrix Mu11A & B oligonucleotide arrays, and staining and washing of all arrays were performed using the Affymetrix fluidics module according to the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Arrays were stained with the florescent conjugate streptavidin phycoerythrin (SAPE, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and analyzed with the GeneArrayTM scanning each array after (S2) SAPE antibody amplification.

Analysis of Gene Expression Data

The raw images from the S2 scans were scaled to the average chip intensity to correct for differences in hybridization. dCHIP was used to analyze the data with tabulation of the data sets performed in Excel. The data sets were combined and culled of targets with detection p values of <0.05. This value is based on the difference between signals obtained from probe match and probe mismatch spotted arrays and is a statistical indicator of the likelihood that a gene is expressed in a given sample. The absolute difference values for each of three replicates, from the 0-, 3-, 12-, and 18-h time points were used to generate average difference values ± S.D. Probe identity was determined using the Netaffx engine (available on-line). Annotation was performed online via Mouse Genome Informatics (available on-line).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

Array expression data were validated by quantitative PCR using an ABI-7700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) from total RNA harvested from hypoxic cultures and transcribed using the superscript III cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Stratagene). Primer probe pairs were selected using the software program PrimerExpress® for the following targets: egr-1 (Fwd 5′-TGCCCTGTCGAGTCCTGC- 3′, Rev 5′-GGATATGGCGGGTAAGCTCA-3′, Probe 5′-ATCGCCGCTTTTCTCGCTCGG-3′), vegf (Fwd 5′-GACTCGGAATCTCTTGGTGAGTG-3′, Rev 5′-AGGAAGGTGAAGCCCGGA-3′, Probe 5′-TGGGCAGAGCGCCACCAGC-3′), glut-1 (Fwd 5′-TCCTGTTGCCCTTCTGCC-3′, Rev 5′-GGTTCTCCTCGTTACGATTGATG-3′, Probe 5′-CGAGAGCCCCCGCTTCCTGC-3′), hkII (Fwd 5′-GACTCGGAATCTCTTGGTGAGTG-3′, Rev 5′-AGGAAGGTGAAGCCCGGA-3′, Probe 5′-TGGGCAGAGCGCCACCAGC-3′), atf5 (Fwd 5′- CCTCCATTCCACTTTCCT-3′, Rev 5′-AGAAACTGACTCTGCCAAATAG-3′, Probe 5′-ATCCAGTCCATCTCTAGGCTTCCC-3′), and chop-10 (Fwd 5′-GGGACTGAGGGTAGAC-3′, Rev 5′-ACATGGACAGTAATAAACAATG-3′, Probe 5′-AGAGGGCTCGGCTTGCACATA-3′). FAM/TAMRA primer-probe sets were obtained from Synthegen (Houston, TX). Reactions were performed using AmpliTaq Gold master mix under the following thermal cycler conditions (1 cycle × 55 °C/2 min, 1 cycle × 95 °C/10 min, 40 cycles × 95 °C/15 s then 60 °C/1 min). Reactions lacking reverse transcriptase were also run to exclude genomic DNA contamination and the -fold induction calculations for each gene were made using the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method (14). Values represent the average ± S.D. across replicates (n = 6).

Western Blotting

Whole cell lysates were harvested from 2.5 × 106 neurons cultured in 60-mm dishes by first rinsing once with ice-cold PBS and then harvesting after incubation on ice for 10 min with RIPA buffer (Tris-HCl (50 mm, pH 7.4), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate (150 mm NaCl), 1 mm EDTA, 1× protease inhibitor mixture). Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C in a bench top centrifuge, and supernatants were stored at −70 °C. Aliquots of equal volume were resolved by SDS-PAGE (8–15%), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and blocked for 90 min at room temperature in wash buffer (50 mm Tris, 0.9% NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk. Primary antibodies were added with constant agitation overnight at 4 °C, blots were rinsed thee times in wash buffer, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h (diluted 1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), washed, and detected by ECL (Renaissance, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The following antibodies were used: NeuN (Chemicon, Temecula, CA); cleaved caspase-3 and PARP, eIF2α, and p-eIF2αser51 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA); ATF4 (AVIVA, San Diego, CA); Tribbles 3 (A-20 and T-15) and CHOP-10 (B-3 and F-168) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Actin (A4700) was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were rinsed with chilled PBS and fixed for 30 min at 4 °C with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then rinsed 2× with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and treated for 30 min/4 °C in blocking solution (0.15 m NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 4.5% non-fat dry milk, 0.1% Triton X-100). Coverslips were inverted on 70-μl droplets of primary antibody diluted 1:100 in Triton/blotto on Parafilm for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were rinsed three times with blotto (0.05% Triton X-100) and incubated with conjugated secondary antibodies 1 h at room temperature (1:2000, Alexa Dyes, Invitrogen). Coverslips were rinsed three times in PBS (0.05% Triton X-100) and mounted in Mowiol. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Z1 Observer, Plan-Neofluor objectives and the charge-coupled device Orca II camera (Hamamatsu, Japan).

Viral Vectors

The herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) amplicon plasmid CMVeGFPHSVprPuc expressing the enhanced GFP protein was constructed as follows. The amplicon vector HSVprPuc was linearized with AccI and ligated with a CMVeGFP fragment generated by PCR from the vector pC2eGFP (Clontech, Inc., Mountain View, CA). The cDNA for Luciferase was transferred from the pGL3Luc in a similar fashion (Promega). cDNAs for CHOP-10 and the leucine zipper-deficient mutant LZ− were generated by reverse transcription-PCR as described (Fwd 5′-GCTCTAGATGGCAGCTGAGTCCCTG-3′, Rev 5′-GGGGTACCTCATGCTTGGTGCA GGCT-3′, and LZ− Rev 5′-CCGGTACCTATAGCTGTGCCACTTTCCG-3′). Cloned cDNAs were sequence-confirmed and transferred to CMVeGFPHSVprPuc using XbaI and KpnI sites contained within the primer sequences (underlined). HSV amplicon vectors were generated as described (15). GFP titers were determined on NIH3T3 cells and ranged between 1 and 3 × 10−8 gfu/ml with amplicon to helper ratios of 1:1. Neuronal cultures were transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 0.8 12 h prior to hypoxic exposure to allow for transgene expression. The pPRIME miR-based lentiviral shRNA system has been described elsewhere (16). 97-mer antisense oligonucleotides were designed against mouse CHOP using RNAi Central (available on-line) and cloned into pPRIME-CMV-GFP. Plasmid identities were confirmed by sequencing and packaged into infectious particles using the HEK293TN line (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and packaging vectors pCMV-VSVG and pCMVΔR8.2ΔVpr kindly provided by Dr. Planelles (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). Stocks were concentrated by polyethylene glycol centrifugation (System Biosciences) and titered on DIV7 mouse cortical neuronal cultures. The vector pPRIME-CMV-GFP-FF3 containing an insert sequence complimentary to firefly luciferase was used as a vehicle control in the experiments.

Statistical Analyses

Significance testing was performed using either Student's t testing or analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test for post-hoc analyses. Results were considered significant for p values < 0.05.

RESULTS

Defining the Kinetics of Hypoxia-induced Neuron Death

To define the temporal relationship between hypoxia-induced gene expression and neuronal death, we characterized the kinetics of nuclear condensation in DIV7 cortical neuronal cultures exposed to continuous hypoxia (0.5% O2). Neuron loss began within 6 h of exposure (t = 0 versus t = 6 h; 26 ± 1% versus 35 ± 3%, p < 0.05) increasing throughout the experimental period (supplemental Fig. S1A; 24 h, 52 ± 1%, p < 0.001). To investigate the maturation kinetics of this response, we also compared death profiles between cultures fixed immediately after the hypoxic period against sister cultures returned to normoxia (i.e. reperfused) for 24 h prior to fixation and analysis (supplemental Fig. S1B). Minor differences in levels of pyknosis were observed (hypoxia alone, light bars 23.3 ± 2.6% versus hypoxia plus reperfusion, black bars, 29.9 ± 4.3%; p < 0.15). Importantly, paired cultures subjected to trypan blue staining at 24 h show only low levels of uptake (data not shown) indicating that pyknosis in this setting is a surrogate marker for programmed cell death and not cellular necrosis.

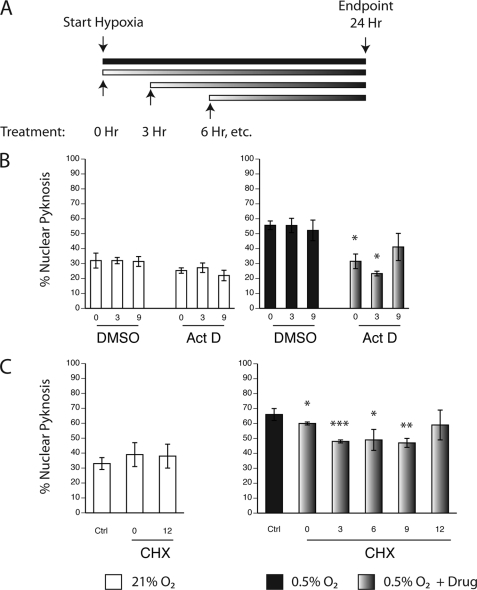

Delayed ischemic preconditioning produces potent neuroprotective effects in a variety of disease models and requires de novo gene expression (13). Reasoning that pro-survival and pro-apoptotic transcriptional responses are activated sequentially, we tested whether the inhibition of gene expression would improve survival by selecting against pathological gene expression. Using a delayed treatment paradigm we treated hypoxic cultures with either the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (ActD) or the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) before, or at various times after the onset of hypoxia (Fig. 1A). Although ActD pretreatment (1 μg/ml) was protective (hypoxia plus ActD T0Hr 31.5 ± 4.9% versus hypoxia alone 55.6 ± 2.9%, p < 0.05), delayed addition enhanced survival to a greater degree (hypoxia plus ActD T3Hr 23.3 ± 1.6 versus hypoxia 55.5 ± 4.8%, p < 0.05). Similarly, although CHX pre-treatment (200 nm) was neuroprotective (hypoxia plus CHX T0Hr, 60 ± 1% versus hypoxia alone 66 ± 4%, p < 0.05), the effect was enhanced if drug was added several hours after hypoxic exposure (hypoxia plus CHX T9Hr, 47 ± 1%, p < 0.01). However, we found that protection was lost if drug delivery was delayed beyond 9 (ActD) to 12 (CXH) h. Neither drug was toxic to control cultures (Fig. 1, B and C, open bars). Thus, continuous euglycemic hypoxia elicits temporally distinct adaptive (<9 h) and pathological (>9 h) phases of gene expression in dissociated neuronal cultures.

FIGURE 1.

Temporal analysis of adaptive and apoptotic gene expression in hypoxic neuronal cultures. A, schematic of the delayed delivery exposure paradigm. To determine the temporal window of pathological transcription and translation required to stimulate nuclear pyknosis in vitro, dissociated cortical cultures maintained under either normoxic (open bars) or hypoxic conditions (filled bars, 0.5% O2), were treated with either vehicle (DMSO), the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D (Act D), or the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) at various points after the onset of hypoxia. B and C, delayed addition of actinomycin D (1 μg/ml in DMSO), or CHX (200 nm) enhances neuronal cell survival in vitro. Cultures were assessed for levels of nuclear pyknosis after 24-h exposure; data are expressed as the absolute fraction of pyknotic nuclei with significance measured by Student's t testing (average ± S.D.; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.005).

Transcriptional Profiling Highlights Putative Survival Genes

To identify the hypoxia-induced factors involved in these responses, we analyzed mRNA expression in cultures exposed to brief (3 h), intermediate (12 h), and extended (18 h) hypoxia using expression microarrays. Because inhibition of gene expression with ActD and CHX implicated induced expression as a modulating influence in the model, we restricted our analyses to genes whose expression were increased ≥ 1.9-fold. Gene hits were annotated and grouped according to their biological function and temporal pattern of expression (Table 1). These groups were associated with transcription (21.5%), stress and oxidative responses (18.1%), carbohydrate metabolism (11.4%), and development (12.5%) consistent with the embryonic origin of the tissue used in the culture model (supplemental Fig. S2). Eight percent of genes were associated with apoptotic signaling, including ddit2 (gadd45γ), ddit3 (chop-10), ddit4 (rtp801), c/EBP-β, prkca, pten, and app (Table 1, bold). Twenty-five percent of transcripts were activated after 3-h exposure and coded for immediate early genes (egr-1, egr-2, c-Jun, ddit2, ddit4, dusp1, ier2, and ier3) or for genes regulated by the hypoxia inducible factor HIF-1α (glut-1, vegf, hmox, adm, hkII, and p4ha1). A second class of transcripts exhibited induction after prolonged exposure (18 h, 27.6%), however, most were activated by 12 h (50.6%) around the time cultured neurons activated apoptotic transition.

TABLE 1.

Results from expression array profiling of hypoxic neuronal cultures

Summary of induced transcripts in hypoxic dissociated cortical neuronal cultures. Dissociated cultures exposed to 0.5% O2 for 3, 12, and 18 h were analyzed using Affymetrix Mu11 SubA&B expression microarrays (n = 3 samples per time point). Genes up-regulated >1.9-fold using a p value cutoff of ≤0.01 comparing test and control samples were selected. Genes were grouped according to their respective MGI gene ontology functions; GenBankTM accession numbers, names, abbreviations, -fold induction (average ± S.D.) and p values are also shown. Targets identified by gene ontology to participate in cell death signaling are highlighted in bold.

| Genebank ID | Gene class/ID | Symbol | -Fold induction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-h |

12-h |

18-h |

||||||

| -fold | p value | -fold | p value | -fold | p value | |||

| Transcription | ||||||||

| NM_007913 | Early growth response 1 | Egr-1 | 7.3 | 0.001 | 8.6 | 0.001 | 6.8 | 0.0001 |

| NM_010118 | Early growth response 2 | Egr-2 | 5.5 | 0.01 | 4.8 | 0.001 | 3.1 | 0.001 |

| NM_010591 | Jun oncogene | c-Jun | 3.1 | 0.001 | 3.5 | 0.0001 | 2.8 | 0.001 |

| NM_029083 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4 | Ddit4 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 3.1 | 0.0001 | 3.0 | 0.001 |

| NM_007498 | Activating transcription factor 3 | ATF3 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_009716 | Activating transcription factor 4 | ATF4 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | 2.2 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_030693 | Activating transcription factor 5 | ATF5 | 2.2 | 0.001 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_009883 | CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β | C/EBP-B | 2.2 | 0.001 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_007837 | DNA-damage inducible transcript 3 | Ddit3 | 12.9 | 0.0001 | 15.3 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_010847 | Max interacting protein 1 | Mxi1 | 2.4 | 0.001 | 2.9 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_173001 | Jumonji domain containing 1A | Jmjd1a | 3.1 | 0.01 | 3.4 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_015786 | Histone cluster 1, H1c | Hist1h1c | 3.5 | 0.001 | 4.2 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_010592 | Jun proto-oncogene-related gene D | Jund1 | 2.9 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_011486 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | STAT3 | 2.1 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_006163 | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2), 45 kDa | NRF2/NF-E2 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_175663 | Histone cluster 1, H2ba | H2ba | 1.9 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_175088 | MyoD family inhibitor domain containing | Mdfic | 2.2 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_133784 | WW domain containing transcription regulator 1 | Wwtr 1 | 2.2 | 0.001 | ||||

| NR_001463 | Inactive X-specific transcripts | XIST | 2.1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| Cell surface/transporter | ||||||||

| NM_011400 | Facilitated glucose transporter, member 1 | Slc2a1/Glut1 | 4.6 | 0.001 | 13.2 | 0.0001 | 12.9 | 0.01 |

| NM_011401 | Facilitated glucose transporter, member 3 | Slc2a3/Glut3 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_009196 | Monocarboxylic acid transporter, member 1 | Slc16a1 | 2.2 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_009166 | Sorbin and SH3 domain containing 1 | Sorbs1 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_009768 | CD147/Basigin | Bsg | 2.7 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_008747 | Neurotensin receptor 2 | Ntsr2 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_010233 | Fibronectin 1 | Fn1 | 2.3 | 0.001 | ||||

| Kinase/phosphatase | ||||||||

| NM_009875 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27) | Cdkn1b | 3.4 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_013642 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | DUSP1/MKP1 | 2.7 | 0.001 | 2.1 | 0.001 | 1.9 | 0.01 |

| NM_130447 | Dual specificity phosphatase 16 | Dusp16/MKP7 | 2.0 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_008828 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Pgk1 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | ||||

| NM_011101 | Protein kinase C, α | Prkca | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_013767 | Casein kinase 1, ϵ | Csnk1e | 2.2 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_016854 | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 3C | Ppp1r3c | 2.7 | 0.01 | 3.6 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_008960 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Pten | 2.4 | 0.01 | ||||

| Development/differentiation | ||||||||

| NM_009390 | Tolloid-like | HMGB2 | 1.9 | 0.001 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | 2.1 | 0.01 |

| NM_009770 | B-cell translocation gene 3 | Btg3 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 2.7 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_008577 | Activator of dibasic neutral A. acid transport, member 2 | CD98/Slc3a2 | 3.0 | 0.00001 | 3.0 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_013703 | Very low density lipoprotein receptor | Vldlr | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_010014 | Disabled homolog 1 (Drosophila) | DAB1 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 2.4 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_010276 | GTP-binding protein | Gem | 3.0 | 0.001 | 2.1 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_009505 | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | VEGF | 5.6 | 0.0001 | 5.7 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_008155 | Glucose phosphate isomerase 1 | Gpi1 | 4.0 | 0.0001 | 5.0 | 0.0001 | ||

| NR_002840 | Growth arrest specific 5 | Gas5 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_013834 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 | Sfrp1 | 1.9 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_010052 | Delta-like 1 homolog (Drosophila) | Dlk1 | 2.1 | 0.01 | ||||

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | ||||||||

| NM_013820 | Hexokinase II | HK2 | 4.7 | 0.001 | 8.1 | 0.0001 | 9.2 | 0.001 |

| NM_008615 | Malic enzyme 1, NADP(+)-dependent, cytosolic | Me1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_008134 | Glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 | Glycam1 | 4.2 | 0.0001 | 3.5 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_029735 | Glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase | Eprs | 2.4 | 0.001 | 2.4 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_023418 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | Pgam1 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | 2.7 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_008826 | Phosphofructokinase, liver, B-type | Pfkl | 2.9 | 0.0001 | 2.5 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_133232 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 | Pfkfb3 | 1.9 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_008155 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | GPI | 3.9 | 0.0001 | 4.3 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_008195 | Glycogen synthase 3, brain | Gys3 | 2.1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| NM_028803 | Glucan (1,4-α), branching enzyme 1 | Gbe1 | 5.2 | 0.001 | ||||

| Stress response/redox signaling | ||||||||

| NM_010442 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | Hmox1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 6.2 | 0.0001 | 7.6 | 0.0001 |

| NM_011030 | Proline 4-hydroxylase, α 1 polypeptide | P4HA1 | 2.5 | 0.01 | 5.8 | 0.0001 | 5.3 | 0.001 |

| NM_009627 | Adrenomedullin | Adm | 3.2 | 0.0001 | 4.5 | 0.001 | 6.1 | 0.001 |

| NM_010499 | Immediate early response 2 | Ier2/pip92 | 3.6 | 0.0001 | 3.9 | 0.0001 | 2.6 | 0.0001 |

| NM_133662 | Immediate early response 3 | Ier3/Gly96 | 3.2 | 0.01 | 7.2 | 0.0001 | 10.4 | 0.000 |

| NM_009150 | Selenium binding protein 1 | Selenbp1 | 2.4 | 0.001 | 2.3 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_022331 | Homocysteine-inducible, ER-stress protein | Herpud1 | 2.2 | 0.001 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_019814 | HIG1 domain family, member 1A | HIGD1A | 2.9 | 0.0001 | 2.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_172943 | AlkB, alkylation repair homolog 5 (E. coli) | Alkbh5 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_002317 | Lysyl oxidase | Lox | 3.8 | 0.01 | 4.7 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_007508 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit A | Atp6v1a1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_027289 | 5′-Nucleotidase domain containing 2 | Nt5dc2 | 2.3 | 0.001 | 2.4 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_011817 | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 gamma | Ddit2 | 3.6 | 0.001 | 3.2 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_011032 | Prolyl 4-hydroxylase, β-polypeptide | P4hb | 1.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_029688 | Sulfiredoxin 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | SRXN1 | 2.1 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_007471 | Amyloid-β (A4) precursor protein | App | 2.2 | 0.01 | ||||

| RNA metabolism | ||||||||

| NM_007755 | Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein | Cpeb1 | 2.1 | 0.01 | 2.4 | 0.01 | ||

| NR_002922 | Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 13 | SNORA13 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 2.8 | 0.001 | ||

| NR_002563 | Small nucleolar SNORD27 | SNORD27 | 2.5 | 0.001 | 2.6 | 0.0001 | ||

| NM_031179 | Splicing factor 3b, subunit 1 | Sf3b1 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 2.2 | 0.01 | ||

| NM_009193 | Stem-loop binding protein | Slbp | 2.1 | 0.0001 | 2.2 | 0.0001 | ||

| Coagulation | ||||||||

| NM_010171 | Coagulation factor III (tissue factor) | TF | 2.6 | 0.01 | 2.6 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_023119 | Enolase 1, α non-neuron | Eno1 | 3.0 | 0.0001 | 3.3 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_008872 | Plasminogen activator, tissue | Plat | 2.3 | 0.001 | 2.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| Other | ||||||||

| NM_009510 | Ezrin/Villin 2 | Ezr/Vil2 | 2.4 | 0.001 | 2.6 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_027491 | Ras-related GTP binding D | Rragd | 3.0 | 0.001 | 2.1 | 0.001 | ||

| NM_182790 | Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor | Pbef1 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_011231 | RAB geranylgeranyl transferase, b subunit | Rabggtb | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_025927 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L45 | Mrpl45 | 2.1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| NM_175628 | α2-macroglobulin | A2m | 2.2 | 0.001 | ||||

| NM_010685 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 | Lamp2 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||

| NM_028057 | Cytochrome b5 reductase 1 | CYB5R1 | 2.6 | 0.001 | ||||

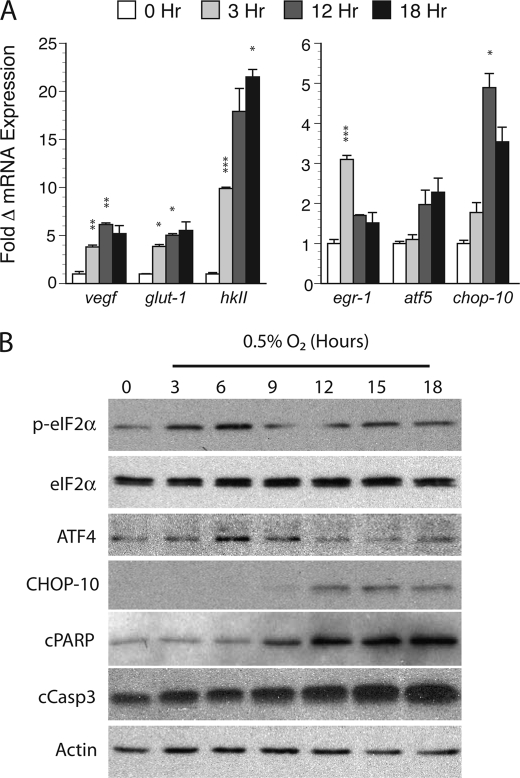

We next validated a set of microarray targets by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Fig. 2A). Expression of the adaptive genes vegf, glut-1, and hkII approximated the array data with peak values ranging between 5.1 ± 0.2-fold (glut-1, 12 h) and 21.5 ± 0.8-fold (hkII, 18 h) with levels remaining elevated throughout the exposure period. The immediate early gene egr-1 exhibited only transient induction (3.1 ± 0.1, 3 h), whereas induction of the bZIP transcription factor chop-10 exhibited delayed kinetics (4.9 ± 0.1-fold at 12 h, p < 0.05). Although induction of the related factor atf5 failed to reach statistical significance, the robust CHOP response coupled with the relative enrichment of this and other bZIP transcription factors suggested that hetero- or homodimeric interactions between the bZIP family may be particularly relevant to cell death signaling in our model (17).

FIGURE 2.

Validation of gene expression in hypoxic cortical neuron cultures. A, quantitative PCR validation of hypoxia-induced microarray targets. RNA prepared from normoxic controls (0 h) or samples exposed to between 3 and 18 h of hypoxia (0.5% O2) was subjected qPCR for the targets vegf, glut-1, hkII, egr-1, atf5, and chop-10. The -fold change in mRNA expression (average ± S.D.) relative to normoxic controls using the ΔΔCT method is shown with significance measured by Student's t testing (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.005; hypoxic versus paired normoxic controls). B, hypoxia activates ER stress and apoptotic targets in cortical cultures exposed to continuous hypoxia (0.5% O2). Samples were analyzed at the indicated times by Western blotting for the following targets: phosphorylated and total eIF2α (p-eIF2α), ATF4, CHOP-10, cleaved PARP (cPARP), cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp3), and actin.

Given the importance of CHOP-10 in ER-mediated responses after stroke (18, 19), we analyzed the temporal activation of factors involved in CHOP signaling by Western blotting. As expected, hypoxia induced both the early and reversible phosphorylation of the elongation factor eIF2α in vitro (3–6 h; Fig. 2B), as well as the induction of the CHOP heterodimeric partner ATF4, due likely to cap-independent, internal ribosome entry site-mediated expression of latent ATF4 transcripts (20, 21). Dephosphorylation of eIF2α and induction of ATF4 also preceded cleavage of both caspase-3 (cCasp3) and its target poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (cPARP). In contrast, CHOP induction occurred much later, suggesting CHOP and ATF4 may have distinct effects on survival.

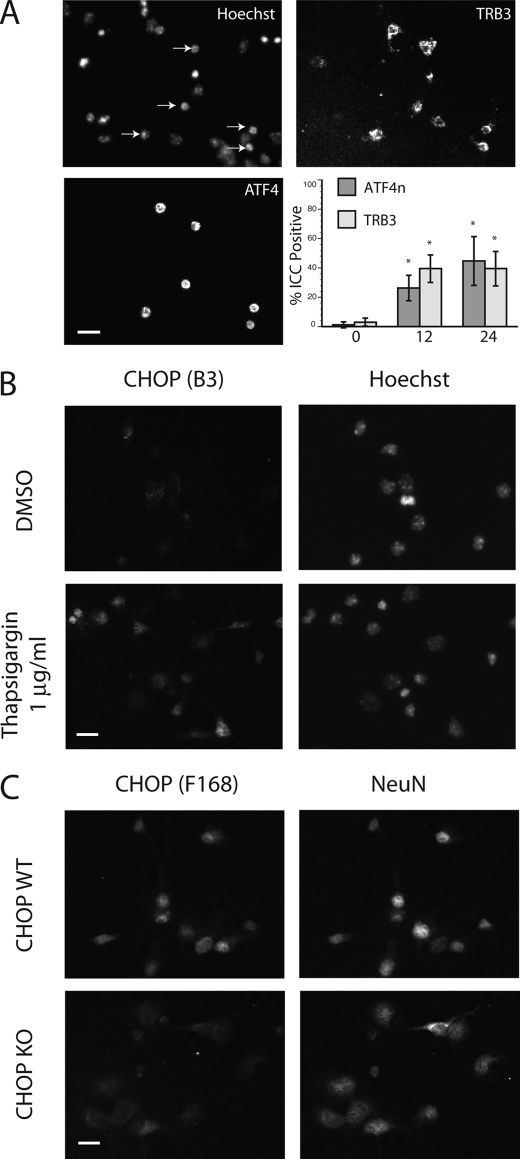

To investigate whether the expression of either ATF4 or CHOP correlated with neuron loss in vitro, we performed immunocytochemistry on dissociated cultures. We observed a time-dependent increase in the total number of neurons expressing ATF4 after hypoxia (Fig. 3A; control 1.2 ± 2% versus 12-h hypoxia 26.3 ± 8.7%). Interestingly, the majority of ATF4-positive cells contained condensed nuclei and co-expressed the ATF4 death-related target Tribbles 3 (Fig. 3A, upper right; control 3.0 ± 2.7% versus 12-h hypoxia 39.5 ± 9.4%). Although cultures exposed to the ER-stress mimetic thapsigargin (Tg, 1 μg/ml) induced nuclear CHOP levels detected using the B3 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 5B), hypoxic exposure failed to induce a comparable response (data not shown). However, using a different antibody (F-168) we identified a form of CHOP exhibiting constitutive expression in the nucleus of cultured neurons under control conditions (Fig. 3C, upper panels). The specificity of staining was confirmed in CHOP knock-out cultures, which demonstrated only faint perinuclear staining (Fig. 3C, lower panels). Although the discrete epitopes recognized by these antibodies are unknown, these results indicate that neuronal CHOP exists in both inducible and constitutively expressed forms. Moreover, unlike ATF4, neither CHOP species exhibited a significant degree of spatial overlap with other cell death markers.

FIGURE 3.

Immunocytochemical analysis of ATF4 and CHOP expression. A, hypoxia-induced ATF4 expression co-localizes with nuclear condensation in neuronal cultures (0.5% O2, 24 h, left panels). Expression of the ATF4 target Tribbles 3 (TRB3) co-localizes with nuclear ATF4 in exposed cultures (top right). Time-dependent increase in ATF4 and TRB3 expression in hypoxic cultures is shown. Data are expressed as the fraction of cells expressing ATF4 or TRB3 (12–24 h, 0.5% O2) relative to untreated controls from an average of 150 cells per coverslip (n = 3). B, broad pattern of CHOP expression in thapsigargin (Tg)-treated cortical cultures. Normoxic cultures were treated with 1 μg/ml Tg for 24 h and analyzed by immunocytochemical analysis using the B-3 monoclonal CHOP antibody. C, a distinct pool of CHOP-10 was expressed widely in cultured embryonic neurons. Double immunocytochemical analysis was performed using the CHOP-reactive polyclonal antibody F-168 and the monoclonal anti-neuronal marker NeuN. Results using CHOP knock-out cultures demonstrate only faint perinuclear staining with the F-168 antisera (scale bar = 20 μm).

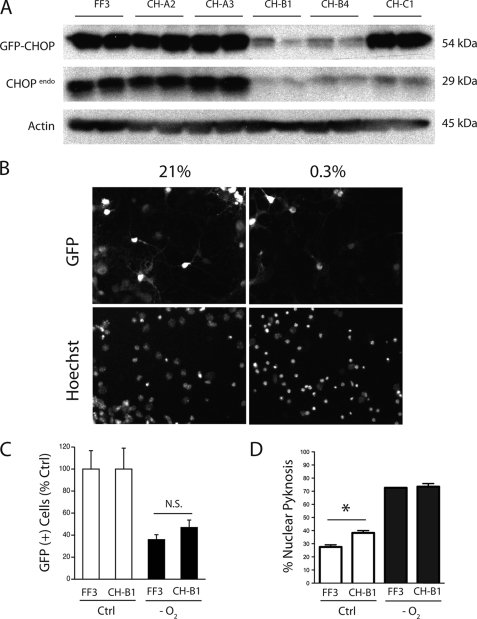

FIGURE 5.

Effects of shRNA-mediated CHOP-10 knockdown on neuron survival. A, pPRIME-CHOP lentiviral transfer vectors were transfected into N2A cells along with the expression vector eGFP-CHOP-V1 and incubated for 72 h before harvesting lysates. Levels of the expressed fusion protein and endogenous CHOP levels were measured by Western blotting and compared with the luciferase targeting control vector pPRIME-FF3 for efficiency of gene silencing. B, fluorescence analysis of GFP expression and nuclear pyknosis in cultures transduced with GFP-expressing pPRIME vectors. C, primary cultures (DIV4) were transduced with either pPRIME-FF3 or pPRIME-CH-B1 lentivirus (multiplicity of infection 0.25), exposed 2 days later to hypoxia (24 h, 0.3% O2, 24 h), and analyzed for the number of surviving GFP-positive cells. D, primary cultures (DIV4) were transduced with pPRIME-FF3 or pPRIME-CH-B1 lentivirus (multiplicity of infection 0.75) and exposed to hypoxia (DIV6, 24 h, 0.3% O2) prior to nuclear pyknosis analysis (DIV9). Results are presented as the average ± S.D. levels of nuclear pyknosis. Significance testing was performed by analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test for post-hoc analyses (*, p < 0.05).

Effect of CHOP Loss of Function on Neuronal Responses to Injury

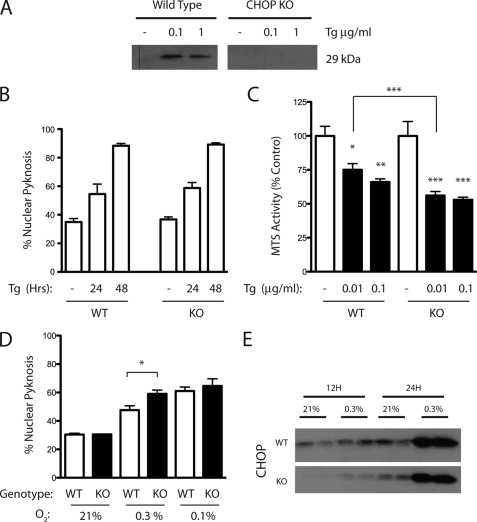

Given reports of reduced neuronal injury in chop−/− mice after stroke (19), we studied whether similar cell death responses would be observed in chop−/− cortical cultures. As expected, Tg treatment stimulated CHOP expression in wild-type but not knock-out cultures (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, CHOP loss of function had no effect on Tg-induced neuron loss measured using the nuclear pyknosis and MTS assays (Fig. 4, B and C, respectively) unless the dose of drug used was reduced from 100 to 10 ng/ml. Moreover, in this lower dose range loss of CHOP exacerbated neuronal injury (Fig. 4C, WT 75.1 ± 11.0% versus KO 56.2 ± 7.1%, p < 0.001). Similarly CHOP loss of function exacerbated levels of nuclear pyknosis after hypoxic challenge (WT 47.6 ± 6.1% versus KO 59.1 ± 5.3%, p < 0.05). Again, this difference disappeared under more extreme conditions (Fig. 4D, compare 0.3% versus 0.1% O2, WT 61.0 ± 5.5% versus KO 64.6 ± 10.1%, p < 0.56). Western analysis performed in sister cultures indicated that, although cCasp3 levels were reduced in chop−/− cultures both basally and early in the hypoxic period, cCasp3 levels in the two genotypes were equivalent after 24-h exposure (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of CHOP deletion on neuron survival. A, detection of CHOP-10 protein by Western blotting in wild-type but not knock-out (KO) cultures following Tg exposure (1 μg/ml, 24 h; DMSO vehicle control shown). B, pyknosis responses of wild-type (WT) and KO cultures exposed to DMSO (−) or Tg (1 μg/ml). C, survival analysis in WT and KO cultures exposed to DMSO (open bar) or two Tg doses (10–100 ng/ml; n = 6 per condition). D, profiles of nuclear pyknosis in WT and KO cultures induced by hypoxic challenge (0.3% versus 0.1% O2, 24 h). Results represent the average ± S.D. Significance testing as performed by analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test for post-hoc analyses is shown (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001). E, Western analysis for levels of cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp3) in WT and KO cultures.

To control for possible compensatory changes occurring in the knock-out background, we tested whether shRNA-mediated knockdown of CHOP would alter survival in wild-type cultures. Western screens in shRNA-transfected N2A cells highlighted sequences that reduced proteins levels of both a transfected exogenous GFP-CHOP fusion as well as endogenous CHOP expression by 90% (CH-B1) compared with control samples transfected with a shRNA transfer vector designed against the firefly luciferase sequence (Fig. 5A, FF3). Lentiviral vectors prepared using the FF3 and CH-B1 transfer vectors were used to infect primary cultures prior to challenge. The effects of shRNA delivery were assessed both indirectly by counting the number of remaining cells expressing GFP from the shRNA transfer vector, as well as directly by assessing fractional nuclear condensation in the entire sample (Fig. 5B). GFP survival analyses demonstrated a non-significant trend toward protection in cultures receiving the CHOP shRNA vector (FF3 35.9 ± 4.6% versus CH-B1 46.9 ± 6.8%; Fig. 5C). Similarly, while CH-B1 delivery induced low level nuclear pyknosis in normoxic cultures, CHOP knockdown had no effect on neuron survival after hypoxia (Fig. 5D).

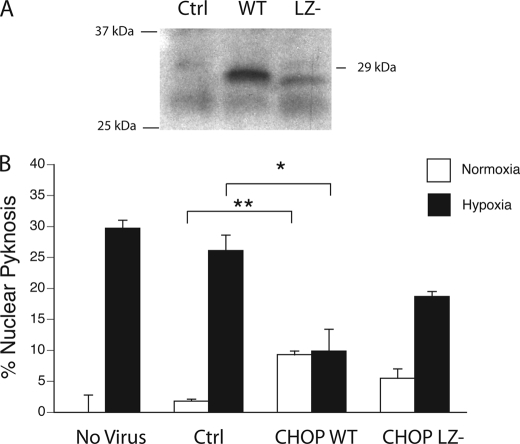

Because the results from both the knock-out and knockdown paradigms suggested that CHOP serves an adaptive role in cortical neurons, we tested whether enforced expression of CHOP could protect cells against injury in a pre-treatment paradigm. Western analysis on HEK293 cultures transfected with amplicon constructs confirmed expression of the WT and leucine zipper-deleted (LZ−) CHOP species at the expected sizes (Fig. 6A). Although control amplicon packaged into HSV-1 virus had no effect on levels of nuclear pyknosis (no virus 29.7 ± 1.2% versus Ctrl 25.7 ± 2.5%), delivery of full-length CHOP induced low level toxicity (Fig. 6B, Ctrl 2.0 ± 0.1% versus WT 9.3 ± 0.6%; p < 0.01). Nonetheless, CHOP expression protected neurons against hypoxia (Ctrl 25.7 ± 2.5% versus WT 9.7 ± 3.8%, p < 0.05). Protection was lost in cultures receiving virus expressing the LZ− construct (Ctrl 25.7 ± 2.5% versus LZ− 18.7 ± 0.6%, p = 0.056). Although this difference may be attributable in part to the relative instability of the LZ− fragment, our results support the hypothesis that CHOP-mediated protection requires protein-protein interactions encoded by the leucine zipper motif.

FIGURE 6.

Enforced CHOP-10 expression protects neurons against hypoxia. A, Western blotting confirms amplicon vectors encoding full-length (WT) and truncated forms of CHOP lacking the leucine zipper (LZ−) are expressed after transfection in HEK293 cells. B, DIV6 cortical neuronal cultures were transduced with amplicon virus (multiplicity of infection 0.7) expressing full-length CHOP, the LZ− mutant, or luciferase as a control 12 h prior to hypoxic challenge. Levels of nuclear pyknosis were assessed in non-transduced (no virus) or virally transduced cultures exposed control and hypoxic conditions (24 h, 0.5% O2). Results are presented as the average ± S.D. levels of nuclear pyknosis (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01) after subtracting background levels of spontaneous nuclear pyknosis.

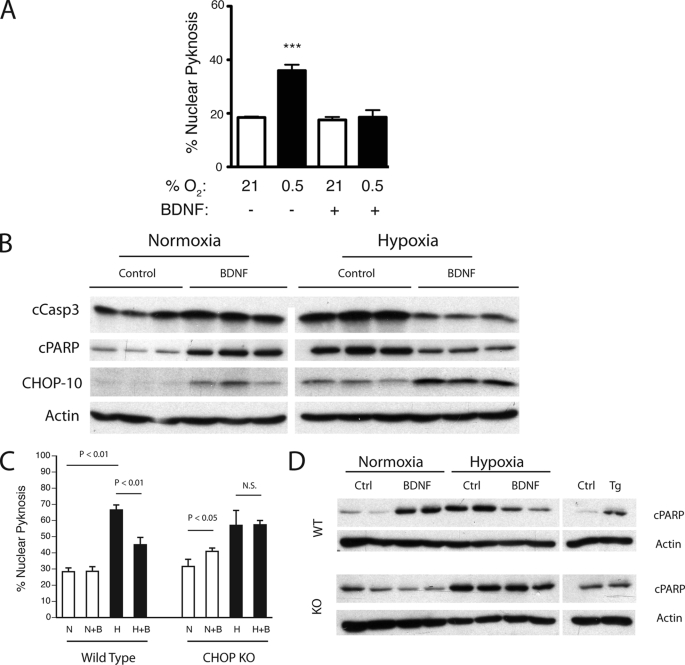

In addition to its role as a neuroprotective factor in post-treatment models of ischemia (22), BDNF pre-treatment blocks activation of caspase-3 after neonatal ischemia (23). As expected, BDNF treatment inhibited nuclear pyknosis in hypoxic cultures (Fig. 7A). To determine whether CHOP protection occurs through conserved preconditioning signaling mechanisms, we studied the effects of the BDNF in our model system. As expected, hypoxia induced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and enhanced CHOP expression. And, while BDNF had no effect on nuclear pyknosis in normoxic cultures (Fig. 7C, WT N+B versus N), BDNF stimulated cCasp3 cPARP and CHOP-10 accumulation. Interestingly, although BDNF reduced cCasp3 and cPARP levels in hypoxic cultures, the combination of hypoxia and BDNF had a synergistic effect on levels of CHOP protein (Fig. 7B, hypoxia-control versus hypoxia-BDNF). Thus, BDNF-induced CHOP accumulation correlated with enhanced neuron survival compared with untreated hypoxic controls in which lower levels of CHOP induction were observed.

FIGURE 7.

CHOP is required for BDNF-mediated protection. A, BDNF (50 ng/ml) pretreatment (12 h, n = 3) protects cortical neurons against hypoxic injury (0.5% O2, 24 h). B, Western analysis of control and BDNF-treated (50 ng/ml) wild-type primary cortical cultures before and after hypoxic challenge (0.3% O2, 24 h). C, wild-type and CHOP knock-out cultures were treated with BDNF as above and analyzed by Hoechst analysis after incubation at normoxic (N and N+B) or hypoxic (H and H+B) conditions. Survival data were derived from an average of 250 counts per coverslip (n = 3; average ± S.D.). D, analysis of lysates from C for levels of cleaved PARP and actin. Control samples exposed to either DMSO (ctrl) or thapsigargin (Tg, 100 ng/ml) are shown. Significance testing was performed by analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test for post-hoc analyses (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001).

To directly test whether CHOP is required for neurotrophin-mediated survival, we compared levels of nuclear pyknosis in hypoxic wild-type and chop−/− cultures pre-treated overnight with BDNF. Results demonstrate a small but significant increase in nuclear pyknosis in BDNF-exposed chop−/− cultures. However, CHOP loss of function attenuated BDNF-mediated hypoxic protection (Fig. 7C, compare WT versus KO, and H versus HB). Western analyses of cPARP levels from matched samples indicated that CHOP was also required for BDNF-induced PARP cleavage in normoxic samples. And although loss of CHOP had no effect on levels of cPARP in hypoxic cultures, the suppressive effect of BDNF treatment on PARP cleavage observed in wild-type hypoxic samples was severely attenuated in the knock-out cultures (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we sought to understand the molecular events controlling cell autonomous death signaling in hypoxic neurons. By correlating the temporal phases of cell death with trends in gene expression, our studies indicate that hypoxia activates temporally and qualitatively distinct gene expression patterns in vitro, and that, in general, selective inhibition of delayed gene expression enhances cell survival potentially by sparing early phase adaptive gene expression. In the course of validating results from the array screen, we also found that continuous hypoxia induced the delayed expression of the bZIP transcription factor CHOP-10, which appeared to serve a protective role in cultured neurons. These data challenge the popular notion that CHOP functions mainly as a pro-apoptotic player after ER stress and suggest that, in certain contexts, CHOP may participate in delayed adaptation in cortical neurons (24, 25).

Cell autonomous transcriptional responses may be particularly relevant in certain stroke subtypes such as neonatal hypoxia-ischemia and global cerebral ischemia (26). However, although genomic studies performed using in vivo models are information-rich and arguably more relevant to the disease in humans, understanding neuron-specific transcription is complicated by responses in glia, vascular endothelium, and immune cells among others. Additionally, discerning relevant transcriptional changes from generic transcriptional routines in such complex data sets can be time consuming, especially because up to 10% of genes in the rodent brain are ischemia-responsive (27, 28). For these reasons, we pursued a reductionist approach to study the cascade of transcriptional responses occurring in dissociated cortical neurons after a stroke-relevant stimulus. To this end, we developed a model of gradual euglycemic-hypoxia rather than use oxygen-glucose deprivation. This allowed us to study gene expression-dependent processes without the confounding influence of necrotic cell death. Although in vitro systems are by no means a surrogate for in vivo studies, this approach allowed us to isolate physiological parameters, efficiently analyze transcriptional trends, and probe for cell-type-specific differences in the regulation of candidate genes with putative adaptive and pathological properties.

In our model the initial adaptive hypoxic period (0–6 h) was characterized by immediate early gene expression, expression of HIF1-α target genes, and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α, which based on previous reports would confer cytoprotective effects (29). A second phase (6–12 h) heralded by dephosphorylation of eIF2α and recovery from translational arrest was associated with the expression of ATF4, induction of the pro-apoptotic target TRB3, and the accumulation of cCasp3, cPARP, and nuclear condensation. Functional annotation of the array results indicated that a cohort of ER stress-associated factors, including the bZIP proteins c/EBP-β, chop-10, atf3, and atf4 was also involved. This was not surprising, because hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and amino acid deprivation, which are all associated with tissue ischemia, also activate sensor proteins located in the ER (30). And although several genes implicated in apoptotic signaling were identified (ddit2, ddit3, ddit4, pten, and app) many adaptive transcripts were also discovered (herpud1 and orp150) suggesting the contemporaneous activation of survival and apoptotic transcriptional pathways in exposed cultures.

Although the hypoxia-induced expression of CHOP correlated temporally with the onset of programmed cell death in our in vitro model, we were unable to corroborate reports linking CHOP function with ischemic neuronal injury (25, 31). For example, Tajiri et al. found that CHOP deletion was neuroprotective in vitro and after transient bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. Several differences between our studies may help explain these conflicting results. Although differences in both neuronal subtype and the age of neurons in culture can produce marked effects on neuron survival, the use of transient injury models with reperfusion by Tajiri et al. is noteworthy. As we have shown, continuous hypoxia without reperfusion induced a prolonged period of eIF2α phosphorylation and presumably translational arrest. We expect that this adaptive response would not have been activated as strongly after transient exposure. Similarly, it is unlikely that a transient ischemic stimulus would stimulate early phase protective transcripts (vegf, Hexokinase II, glut-1, glut-3, etc.) to the degree observed with our paradigm. As for the results from their in vivo studies, it is possible that CHOP signaling in glia or other non-neuronal constituents could exert indirect, toxic effects on neuron survival that would not otherwise have been seen in the dissociated cultures. Future studies in conditional cell-type-specific loss of function models should shed light on this question.

There is precedent for CHOP serving an adaptive role in other CNS disorders (38). In addition, the fact that CHOP is expressed in both the selectively vulnerable (CA1) and resistant (CA3) sections of the hippocampus after transient forebrain ischemia suggests that the use of CHOP expression levels as a surrogate marker for cell death requires re-examination (32). In our system, healthy appearing neurons cultured under control conditions contained immunologically distinct pools of CHOP protein. This is not surprising, because CHOP's transcriptional potency and apoptotic potential are regulated by post-translational modification (33). Thus, the ability of CHOP to induce cellular injury would depend on the balance of adaptive versus pathological modifications to the cellular complement of CHOP. In this regard, induction of low level toxicity by expression of the transgene may have saturated the adaptive pathways required to attenuate its apoptotic potential. Alternatively, our data regarding the activity of the CHOP (LZ−) suggest that heterodimeric interactions may also be important in determining the biological effects of CHOP. Although capable of homodimerization, CHOP exhibits a higher affinity for other bZIP factors, including the CAAT-enhancer binding proteins (c/EBPβ, -γ, -δ, and -ϵ), ATF2, -3, -4, and -7, and bATF (34). Data from our laboratory and others indicate that CHOP:c/EBP-β heterodimers may be particularly important for adaptation through the induction of genes, including those involved in the amino acid starvation (asn) and heat shock responses (Cnp60/10 and orp150) (35). CHOP also activates expression of GADD34 and the ER-specific oxidoreductase ERO1-L-α and represses transcription of the pro-survival gene bcl-2, thus linking it with apoptotic signaling (36, 37). Our data regarding the expression of ATF4 and TRB3 in dying neurons is consistent with a recent report demonstrating ATF4 knock-out mice are protected from stroke (24). The ability of CHOP to participate in both adaptive and pathological transcriptional responses suggests that, although necessary, it alone is not sufficient to support neuronal apoptosis. Given the marked promiscuity between members of the bZIP family it is reasonable to assume that the stoichiometry between c/EBP-β, ATF4, CHOP-10, and other bZIP proteins will influence neuron survival in the peri-ischemic period.

Our finding that CHOP loss of function attenuated BDNF-mediated protection was unexpected. BDNF exerts potent neuroprotective effects through its actions on the Akt pathway (23). However, although BDNF influences the spatial distribution of CHOP in TrkB overexpressing cell lines (39), to the best of our knowledge our observation is the first demonstrating that BDNF increases CHOP protein levels in primary neurons. CHOP transcription is regulated in part by several bZIP proteins, including ATF4, ATF6, and Xbp-1. Because BDNF stimulates neurite outgrowth by enhancing IRE-1α-mediated splicing of Xbp-1 (40), it is likely that IRE-1α-mediated processing of Xbp-1 is involved. The recent proposal that the PERK-ATF4 signaling axis promotes cell death, whereas IRE1α-dependent activation of Xbp-1 appears to be cytoprotective (41) also raises an interesting dichotomy regarding the role of CHOP in cellular signaling. Because CHOP transcription is responsive to both ER pathways, it is interesting to speculate that, rather than exerting a qualitative influence on ER stress signaling, the delayed expression of CHOP in prolonged hypoxia may be particularly important in regulating the amplitude of the transcriptional response and its attendant cell biological actions.

Supplementary Material

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DIV

- days in vitro

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- cPARP

- cleavage of PARP

- cCasp3

- cleavage of caspase-3

- HSV

- herpes simplex virus

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- ActD

- actinomycin D

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- Tg

- thapsigargin

- WT

- wild type

- KO

- knock-out

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- Ctrl

- control.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bredesen D. E. (2007) Stroke 38, 652–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirino T., Tamura A., Sano K. (1984) Acta Neuropathol. 64, 139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du C., Hu R., Csernansky C. A., Hsu C. Y., Choi D. W. (1996) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 16, 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konaka K., Miyashita K., Naritomi H. (2007) J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 16, 82–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shigeno T., Yamasaki Y., Kato G., Kusaka K., Mima T., Takakura K., Graham D. I., Furukawa S. (1990) Neurosci. Lett. 120, 117–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum D. M., Michaelson M., Batter D. K., Doshi P., Kessler J. A. (1994) Ann. Neurol. 36, 864–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krajewski S., Mai J. K., Krajewska M., Sikorska M., Mossakowski M. J., Reed J. C. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 6364–6376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dave K. R., Raval A. P., Prado R., Katz L. M., Sick T. J., Ginsberg M. D., Busto R., Pérez-Pinzon M. A. (2004) Brain Res. 1024, 89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teschendorf P., Padosch S. A., Spöhr F., Albertsmeier M., Schneider A., Vogel P., Choi Y. H., Böttiger B. W., Popp E. (2008) Neurosci. Lett. 448, 194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross D. T., Graham D. I. (1993) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 13, 558–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khot S., Tirschwell D. L. (2006) Semin. Neurol. 26, 422–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirino T. (2000) Neuropathology 20, (suppl.) S95–S97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gidday J. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 437–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geschwind M. D., Lu B., Federoff H. J. (1994) Methods Neurosci. 21, 462–482 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stegmeier F., Hu G., Rickles R. J., Hannon G. J., Elledge S. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13212–13217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halterman M. W., De Jesus C., Rempe D. A., Schor N. F., Federoff H. J. (2008) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 38, 125–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange P. S., Chavez J. C., Pinto J. T., Coppola G., Sun C. W., Townes T. M., Geschwind D. H., Ratan R. R. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 1227–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajiri S., Oyadomari S., Yano S., Morioka M., Gotoh T., Hamada J. I., Ushio Y., Mori M. (2004) Cell Death Differ. 11, 403–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeGracia D. J., Montie H. L. (2004) J. Neurochem. 91, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bert A. G., Grépin R., Vadas M. A., Goodall G. J. (2006) RNA 12, 1074–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäbitz W. R., Sommer C., Zoder W., Kiessling M., Schwaninger M., Schwab S. (2000) Stroke 31, 2212–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han B. H., Holtzman D. M. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 5775–5781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohoka N., Yoshii S., Hattori T., Onozaki K., Hayashi H. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1243–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tajiri S., Yano S., Morioka M., Kuratsu J., Mori M., Gotoh T. (2006) FEBS Letters 580, 3462–3468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S., Shi H., Liu W., Furuichi T., Timmins G. S., Liu K. J. (2004) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24, 343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J. B., Piao C. S., Lee K. W., Han P. L., Ahn J. I., Lee Y. S., Lee J. K. (2004) J. Neurochem. 89, 1271–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin K., Mao X. O., Eshoo M. W., Nagayama T., Minami M., Simon R. P., Greenberg D. A. (2001) Ann. Neurol. 50, 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y., Fenik P., Zhan G., Sanfillipo-Cohn B., Naidoo N., Veasey S. C. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 2168–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding H. P., Calfon M., Urano F., Novoa I., Ron D. (2002) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 575–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinszner H., Kuroda M., Wang X., Batchvarova N., Lightfoot R. T., Remotti H., Stevens J. L., Ron D. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 982–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oida Y., Shimazawa M., Imaizumi K., Hara H. (2008) Neuroscience 151, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X. Z., Ron D. (1996) Science 272, 1347–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman J. R., Keating A. E. (2003) Science 300, 2097–2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aldridge J. E., Horibe T., Hoogenraad N. J. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marciniak S. J., Yun C. Y., Oyadomari S., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Jungreis R., Nagata K., Harding H. P., Ron D. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 3066–3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCullough K. D., Martindale J. L., Klotz L. O., Aw T. Y., Holbrook N. J. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 1249–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Southwood C. M., Garbern J., Jiang W., Gow A. (2002) Neuron 36, 585–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G., Fan Z., Wang X., Ma C., Bower K. A., Shi X., Ke Z. J., Luo J. (2007) J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1674–1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma Y., Hendershot L. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13792–13799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin J. H., Li H., Yasumura D., Cohen H. R., Zhang C., Panning B., Shokat K. M., Lavail M. M., Walter P. (2007) Science 318, 944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.