Abstract

Multiple Ca2+ release and entry mechanisms and potential cytoskeletal targets have been implicated in vascular endothelial barrier dysfunction; however, the immediate downstream effectors of Ca2+ signals in the regulation of endothelial permeability still remain unclear. In the present study, we evaluated the contribution of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) as a mediator of thrombin-stimulated increases in human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) monolayer permeability. For the first time, we identified the CaMKIIδ6 isoform as the predominant CaMKII isoform expressed in endothelium. As little as 2.5 nm thrombin maximally increased CaMKIIδ6 activation assessed by Thr287 autophosphorylation. Electroporation of siRNA targeting endogenous CaMKIIδ (siCaMKIIδ) suppressed expression of the kinase by >80% and significantly inhibited 2.5 nm thrombin-induced increases in monolayer permeability assessed by electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS). siCaMKIIδ inhibited 2.5 nm thrombin-induced activation of RhoA, but had no effect on thrombin-induced ERK1/2 activation. Although Rho kinase inhibition strongly suppressed thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability, inhibiting ERK1/2 activation had no effect. In contrast to previous reports, these results indicate that thrombin-induced ERK1/2 activation in endothelial cells is not mediated by CaMKII and is not involved in endothelial barrier hyperpermeability. Instead, CaMKIIδ6 mediates thrombin-induced HUVEC barrier dysfunction through RhoA/Rho kinase as downstream intermediates. Moreover, the relative contribution of the CaMKIIδ6/RhoA pathway(s) diminished with increasing thrombin stimulation, indicating recruitment of alternative signaling pathways mediating endothelial barrier dysfunction, dependent upon thrombin concentration.

Keywords: Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase (CaMK), Endothelium, ERK, Rho, Thrombin

Introduction

Endothelial cells line the luminal surface of blood vessels where they regulate the flux and/or transport of fluid, macromolecules and white blood cells from the vascular space to the interstitium. A loss of barrier function as found with inflammation leads to the accumulation of fluid that can disrupt tissue function. Thrombin, a key pro-coagulant serine-protease, is a well known inflammatory mediator that induces endothelial barrier dysfunction by activating endothelial expressed protease-activated receptors (PARs), resulting in activation of key signaling pathways, including increases in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), that mediate cytoskeletal reorganization through myosin light chain (MLC)-dependent EC contraction (1) and the disassembly of VE-cadherin containing adherent junctions (2). Multiple Ca2+ release and entry mechanisms may contribute to agonist-dependent increases in [Ca2+]i in endothelial cells including Oria1/STIM1-mediated pathways (3) and various TRP channels (4), including TRPC4 plasma membrane channels (5, 6). However, the immediate downstream effectors of Ca2+ signaling pathways in the regulation of EC permeability still remain unclear.

A number of Ca2+/calmodulin activated serine/threonine protein kinases, including Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII),2 have been reported to mediate diverse actions of Ca2+ signals in various types of cells (7). CaMKII is a ubiquitous multifunctional protein kinase, with complex structural and autoregulatory properties. Four primary isoforms are encoded by separate homologous genes (α, β, δ, γ), each of which is alternatively spliced to produce a larger number of isoform variants. Evidence suggests structural diversity in CaMKII isoform variants is an important determinant of cellular function (8, 9). We have established that CaMKII plays important roles in regulation of contraction, proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle (VSM) (10–15). In pulmonary artery endothelial cells, CaMKII has been linked to thrombin-induced increases in monolayer permeability (hyperpermeability) (16) through activation of ERK1/2 (17) and filamin phosphorylation (16). However, these conclusions are based largely on pharmacological approaches (KN-62, KN-93) aimed at selectively inhibiting CaMKII activity and/or consequences of CaMKIIα isoform overexpression, an isoform mainly restricted to neuronal tissue (18). Because of the lack of knowledge on which isoforms predominate in endothelial cells, and potential non-specificity of KN62/KN93, the role and mechanisms of endogenous CaMKII isoforms in endothelial barrier function still remains unclear. Characterization of the endogenous CaMKII isoform(s) expressed in endothelium followed by specific molecular approaches, such as loss-of-function small interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing, would provide a valuable approach to resolve the functional importance of endogenous CaMKII in regulating thrombin-induced EC barrier dysfunction.

In the present study, we identified the δ6 isoform as the predominant endogenous CaMKII isoform in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). CaMKIIδ6 lacks an alternatively spliced 21 amino acid C terminus present in the more common CaMKIIδ variants such as the δ2 and δ3 (δC and δB, by alternative nomenclature) expressed, for example, in VSM or heart. Loss-of-function siRNA approaches were used to evaluate the functional role of the CaMKIIδ6 isoform in thrombin-induced HUVEC signaling and hyperpermeability (or barrier dysfunction). Our data indicate that CaMKIIδ6 mediates thrombin-induced HUVEC barrier dysfunction through RhoA/Rho kinase as downstream intermediates. In contrast to previous studies using alternative approaches to manipulate CaMKII activity in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BPAEC) (17), we found that in HUVECs ERK1/2 activation in response to thrombin stimulation was not mediated by CaMKII and was not involved in thrombin-induced hyperpermeability. The relative contribution of the CaMKII/RhoA pathway(s) was only significant in response to low concentration thrombin (2.5 nm) stimulation indicating recruitment of alternative signaling pathways mediating endothelial barrier dysfunction, dependent upon thrombin concentration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from Cascade Biologics (cat. C-015-5C, Portland, OR) and used between passages 3–12. Cells were seeded at 4 × 104 cells/cm2 in HUVEC culture medium (cat. cc-4176, LONZA, Walkersville, MD) and passed every other day. For all experiments, HUVEC were seeded at confluency (1 × 105 cells/cm2) and grown for 3 days to form mature monolayers. Primary cultures of dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMEC) were isolated from human foreskins and grown in HDMEC culture medium (cat. cc-4177, LONZA, Walkersville, MD). Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BAEC) were obtained from Vectec (Rensselaer, NY) and cultured in MEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Rat VSM cells were enzymatically dispersed from thoracic aortas of 200–300 g male Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described (19, 20). Rat VSM were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin.

Antibodies and Reagents

Creation and specificity of the antipeptide polyclonal antibodies recognizing all CaMKII isoforms (panCaMKII), δ isoform variants with the 21-amino acid C terminus (CaMKIIδ2), γ isoforms, and autophosphorylated CaMKII on Thr287 (pCaMKII), were described previously (20–22). The antigen for the antibody selectively recognizing CaMKIIδ variants lacking the 21-amino acid C-terminal tail (CaMKIIδ6) was CaMKIIδ aa465–477 (L13406, BC107562). Other antibodies used include anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling), anti-β-actin (Sigma), and anti-RhoA (Cytoskeleton). All cell culture medium and supplies were from Fisher Scientific unless otherwise specified. Other reagents used include thrombin (Sigma), U0126 (Calbiochem), Y27632 (Krackeler Scientific, Albany, NY), Ionomycin (Calbiochem), and Fura-2AM (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA).

Measurement of Transendothelial Electric Resistance (TEER)

ECIS 1600R (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY), electric cell-substrate impedance sensing system, was used to measure TEER (a measure of endothelial barrier integrity) of HUVEC monolayers as described in detail by Giaever and Keese (23). Briefly, HUVEC (1 × 105 cells/cm2) were plated in a well containing 10 small gold electrodes and a larger counter electrode. After attachment to ECIS, cells were allowed to equilibrate in serum-free medium (EBM-2, LONZA, Wakersville, MD) for 4 h. Once resistances were relatively constant (1400–1700 Ω), treatments (thrombin, U0126. or Y27632) were added directly to the wells at the indicated times. Resistance was measured every 3 min for the duration of the experiments. Data were normalized to the mean resistance over the course of 1 h immediately before thrombin addition and after preincubation with DMSO (vehicle), U0126, and Y27632 for different purposes of experiments.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from HUVEC, HDMEC, BAEC, or rat VSM using the mirVana miRNA Isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA concentration was measured by absorbance at 260/280 nm with a Beckman Coulter DU 640 spectrophotometer. RNA (1 μg) was converted to cDNA using reverse transcriptase (RT) and 0.2 μg of random hexamer primers (Invitrogen) with Ready-TO-Go beads (Amersham Biosciences). cDNA (1 μl of reverse transcription products per 20-μl PCR reaction) was amplified on an Tetrad Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) using TaqPCR Master Mix kit(Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with the standard protocol defining cDNA, primer, distilled H2O, and Master Mix concentrations. Based on the human/rat CaMKII δ sequences (NM_001221, NM_012519), PCR primers specifically targeting δ-gene products were designed as following: primers for targeting TV1 exon: 5′-forward primers (human & rat: 5′-GCC ATC TTG ACA ACT ATG CTG GCT); 3′-reverse primers (human: 5′-CGT GCT TTC ACA TCT TCA TCC TCA; rat: CGT GCT TTC ACG TCT TCA TCC TCA); Primers for targeting TV2 exon: 5′-forward primers (human: 5′-TAG GCT CAC ACA GTA CAT GGA TGG; rat: 5′-TCG GCT CAC ACA GTA CAT GGA TGG) are located upstream of δ-specific C terminus; 3′-reverse primers (human: 5′-ACA TGC ATG AAG AGG AGG AGA GGA; rat: 5′-GAA ACA TGC ATG AAG AGG AGA GGA) are located in the untranslated region beyond the TV2 alternatively spliced exon encoding the δ-specific C terminus (Fig. 1B). PCR products were analyzed by 2 or 4% agarose gel. The identity of purified PCR products was confirmed by DNA sequencing from GENEWIZ (South Plainfield, NJ) with our relative 5′-forward primers.

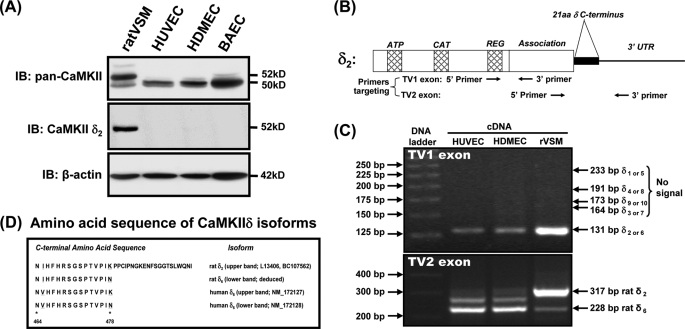

FIGURE 1.

CaMKIIδ6 isoform expression in endothelial cells. A, confluent endothelial monolayers from human umbilical vein (HUVEC), human dermal microvasculature (HDMEC) bovine aorta (BAEC), or control rat aortic vascular smooth muscle (ratVSM), were lysed and immunoblotted with antibodies recognizing; all CaMKII isoforms (IB: pan-CaMKII), the alternatively spliced C-terminal sequence in CaMKIIδ2 (IB: CaMKIIδ2), or β-actin as a loading control. B, location of PCR primers targeting TV1 and TV2 exons were designed based on human and rat CaMKIIδ (NM_001221, NM_012519). C, RT-PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Top panel: for TV1 exon primers, products from HUVEC share the same TV1 domain of rat δ2 with a predicted product of 131 bp. Bottom panel: for TV2 exon primers, the main products differed in size between VSM and endothelial cell sources. The predicated sizes of rat δ2 (317 bp) and rat δ6 (228 bp) are indicated. D, predicted C-terminal amino acid sequences of the main products confirm δ2 expression in rat VSM (with a small amount of δ6). Two δ6 transcript variants ending with different amino acids (K or N) were identified as the predominant isoforms in HUVECs.

siRNA Electroporation

Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool (cat. L-004042-00-0020; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO) siRNA specifically targeting human CaMKIIδ were electroporated in HUVEC cells. Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL Nontargeting siRNA No. 1 (cat. L-001810-01-20) was used as control siRNA. Electroporation was performed as follows: subconfluent HUVEC cells were removed from the culture dish by addition of trypsin, washed, and resuspended in siPORT siRNA Electroporation Buffer (Ambion) at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/cuvette with 10 μg of the respective siRNA. Cells were electroporated with one 0.15-ms pulse of 300 V (Gene Pulser II, Bio-Rad). After an additional incubation for 10 min at 37 °C, cells were plated on the appropriate culture dishes and on the following day, medium was removed and replaced by fresh HUVEC culture medium. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blot 48 h, 96 h after electroporation.

Western Blotting

Cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 during the pretreatment. Reactions were stopped by removal of HBSS++ and transfer of the dishes to ice, and cells were lysed (0.25 ml/35-mm dish) in a modified radioimmune precipitation assay buffer composed of 10 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm NaF, 20 mm Na4P2O7, 2 mm Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 10% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.2 units/ml aprotinin. The lysates were collected into ice-cold 1.5-ml tubes and cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. Lysates were resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TBST) and 5% nonfat dry milk. After blocking, the membranes were incubated in primary antibody for 1 h at 22 °C, washed three times with TBST, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h at 22 °C followed by washing (three times) with TBST. Membranes were developed using chemiluminescence substrate (Amersham Biosciences); signal intensity was measured with a Fuji LAS4000 Imaging Station, and band intensity was compared using Multi Gauge V3.1. All blots shown are representative of at least three experiments.

Calcium Measurements

Intracellular calcium measurements were performed as described previously (3). Briefly, serum-starved confluent HUVEC monolayers were loaded with 4 μmol/liter Fura-2AM (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min at 37 °C and washed three times with HBSS (GIBCO) containing (mm): NaCl, 140; KCl, 3; MgSO4, 1.2; HEPES, 10; Ca2+, 2; and glucose, 10 (pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Fluorescence was recorded in the absence or presence of different concentrations thrombin incubation and analyzed using a digital fluorescence imaging system (Intracellular Imaging, OH) to measure intracellular free Ca2+ signal (ratio F340/F380) in individual cells in the mature monolayer. Ionomycin (0.5 μm) was added at the end of experiment to establish maximum fluorescence ratios.

RhoA Activation Assay

Rho G-LISA Activation Assays Biochem kitTM (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver CO), was used to measure Rho A activity according to manufacturers recommendations. siRNA electroporated or non-electroporated HUVECs were seeded at confluency and grown for 3 more days to form mature confluent monolayers in 35-mm dishes. Monolayers were washed twice with room temperature EBM and incubated for 4 h before stimulation with HBSS (with 2 mm Ca2+ and 10 mm HEPES) followed by thrombin addition. After indicated time course of thrombin incubation, solutions were aspirated and cell lysis buffer (4 °C) was added to culture dishes placed on ice. Cell lysates were centrifugation at 14,000 (<15,000 × g) at 4 °C for 2 min and an aliquot removed for protein determination. Following adjustment for protein concentration, cell lysates were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C. After thawing, 50 μl of lysate was added to the wells of plates coated with Rho A-binding domain peptides. Additional wells were filled with lysis buffer or non-hydrolysable constitutive active RhoA as negative and positive controls, respectively. Plates were placed immediately on an orbital shaker at 400 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min, washed twice with RT buffer, and 200 μl of antigen-presenting buffer was added to each well for 2 min at room temperature. After three washes, 50 μl of Rho A primary antibody (diluted 1:200 in antibody dilution buffer) was added for 45 min with shaking. Following three washes, 50 μl of secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled antibody (diluted 1:100) was added to each well for 45 min), followed by three washes and addition of 50 μl of HRP detection reagent at 37 °C for 15 min. Finally, 50 μl of HRP stop buffer was added, and the signal measured immediately at 490 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer.

Statistics

Values throughout were expressed as mean ± S.E. Mean values of groups were analyzed using GraphPad PRISM version 4.0, and compared by ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls post-hoc analysis to determine significant differences between groups. For all comparisons, p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of CaMKIIδ6 as the Endogenous HUVEC Isoform

To design specific molecular approaches for probing functions of endogenous CaMKII in endothelial cells, we first identified the CaMKII isoform(s) expressed in several cell lines by Western blotting with CaMKII subtype-specific antibodies. Blotting with a antibody recognizing all CaMKII isoforms (11–14, 19, 22), indicated that the predominant isoform expressed in primary cultures of endothelial cells has an apparent molecular mass of 50 kDa, smaller than the predominant 52-kDa isoform in cultured rat VSM, which we previously identified as the CaMKIIδ2 variant (11, 12, 14, 15) (Fig. 1A, top panel). Blotting with an antibody that specifically recognizes an alternatively spliced 21-amino acid C-terminal domain in CaMKIIδ2 and related δ-gene variants (19, 24, 25) failed to recognize the predominant endothelial isoform (Fig. 1A, middle panel). Western blotting with an antibody recognizing the C terminus of CaMKIIγ gene products, identified a number of higher molecular mass bands (54–64 kDa) in both VSM and endothelial cells (supplemental data S1), but based on corresponding pan-CaMKII signals these were minor isoforms and none corresponded to the predominant 50-kDa band expressed in endothelial cells.

Based on these results and literature indicating restricted expression of CaMKII α and β isoforms in neuronal tissues (18), we postulated that the predominant endothelial isoform was an atypical CaMKIIδ variant, similar to CaMKIIδ2 but lacking an alternatively spliced 21-amino acid C terminus (24, 25). This hypothesis was tested by RT-PCR and sequence analysis of amplified targets using mRNA extracts from human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and δ-gene specific PCR primers spanning the two transcript variable (TV) regions, including TV1 exon, where δ2 differs from δ1,3,4,9 isoforms, and TV2 exon, the alternatively spliced C-terminal exon (24, 25) (Fig. 1B). Analysis of cultured rat VSM mRNA was used as a positive control for CaMKIIδ2 expression (11, 12, 15, 26). Our data showed that the predominant isoform in HUVEC shares the same TV1 exon structure with δ2 in rat VSM (Fig. 1C, top panel) but lacks the TV2 exon at the C terminus in δ2 (Fig. 1C, lower panel). Deduced amino acid sequences of the major endothelial cell TV2 PCR products (and the minor VSM product) identified δ-gene variants lacking the 21-amino acid C terminus (Fig. 1D). The alternative C-terminal lysine (K) and asparagine (N) found on the variants here corresponds with human transcripts reported in GenBankTM (NM_172127; NM_172128).

Finally, to confirm that the predominant expressed CaMKII isoform in endothelial cells was a δ- gene product, we (a) Western blotted with an anti-peptide antibody raised against a conserved C-terminal domain sequence found in all CaMKIIδ variants, and (b) used siRNAs specifically targeting the human CaMKIIδ gene. The δ-specific antibody recognized a 50-kDa band in endothelial cell lysates (supplemental data S1B), precisely corresponding to the band identified with the pan-CaMKII antibody (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, this antibody did not recognize the 52-kDa CaMKIIδ2 variant expressed in VSM, suggesting that the antibody epitope was masked by inclusion of the additional 21-amino acid C-terminal domain, a result that we have confirmed using recombinant CaMKIIδ2 and CaMKIIδ6 protein standards (not shown). Finally, introduction of siRNAs specifically targeting human CaMKIIδ isoforms for 56–96 h down-regulated total CaMKII expression in HUVECs by greater than 80% (Fig. 2, A and B), confirming predominant expression of an endogenous CaMKIIδ isoform in HUVECs.

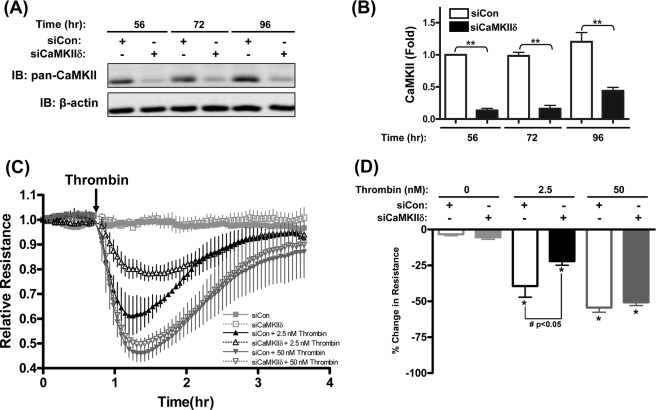

FIGURE 2.

CaMKIIδ mediates low concentration thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability. A, time-dependent siRNA-mediated suppression of endogenous HUVEC CaMKII. siRNAs specific to human CaMKIIδ subunit (siCaMKIIδ, Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool) or scrambled control siRNA (siCon, Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL) were introduced into suspended HUVEC by electroporation cells and seeded at confluency on gelatin-coated dishes for 56, 72, and 96 h in growth medium. Representative immunoblots with pan-CaMKII are shown. B, quantification of siRNA suppression efficacy. The bar graph quantified results from three individual experiments with pan-CaMKII signals normalized to β-actin signals and expressed relative to control siRNA value at 56 h. **, p ≤ 0.01 compared with the siRNA control at the same time point. C, TEER of HUVECs electroporated with siRNAs targeting CaMKIIδ (siCaMKIIδ) or control siRNA (siCon) and stimulated with 2.5 or 50 nm thrombin. Resistance values were normalized to the baseline before thrombin addition, and are plotted as relative resistance units compared with the baseline value set at 1.0. Symbols and ticks indicate the mean and S.E. of relative resistances from three independent experiments, respectively. Decreased resistance reflects increases in permeability. D, quantification of maximal changes in monolayer resistance in experiments shown in C. Peak % changes are relative to baselines prior to addition of thrombin or vehicle control. Data values are means ± S.E. from three independent experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05 effects of thrombin compared with vehicle controls; #, p ≤ 0.05 compared between siCon and siCaMKIIδ groups.

CaMKIIδ Mediates Low Concentration Thrombin-induced HUVEC Hyperpermeability

To determine the effects of thrombin concentration on endothelial monolayer permeability, post-confluent serum-starved HUVEC monolayers were exposed to 1–50 nm (0.0022–0.1100 IU/ml) thrombin and trans-endothelial electric resistance (TEER) was monitored as described in methods. Preliminary experiments determined concentration-dependent responses, with a threshold response of 1 nm thrombin and maximal response at 50 nm thrombin (supplemental data S2A). Thrombin-induced increase in permeability (or hyperpermeability), as reflected by decline of TEER, was transient upon addition of thrombin with maximal responses at 15–20 min followed by a recovery toward control levels over 2 h (supplemental data S2, B and C). Based on these initial experiments, 2.5 nm and 50 nm concentrations of thrombin were chosen as representative low and high concentrations, respectively, for subsequent studies.

siRNA-mediated suppression of CaMKIIδ was used to elucidate the role of this signaling molecule in thrombin-induced HUVEC monolayer hyperpermeability (or barrier dysfunction). As shown in Fig. 2, C and D, siRNA silencing of CaMKIIδ (siCaMKIIδ) significantly inhibited low concentration (2.5 nm) thrombin-induced decreases in HUVEC resistance by 44.0%. Interestingly, siCaMKIIδ had no effect on high concentration (50 nm) thrombin-induced increases in HUVEC permeability. These data confirm a role for endogenous CaMKIIδ6 in mediating thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability (16, 17), but indicate that the relative contribution of CaMKIIδ6 is thrombin concentration-dependent, with alternative CaMKIIδ-independent pathways recruited in response to high concentrations of thrombin.

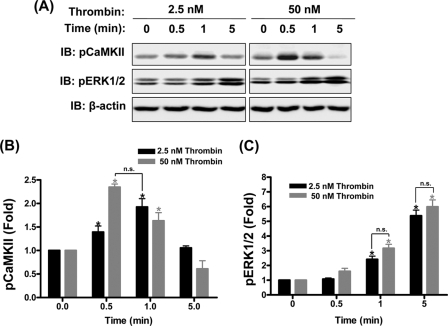

Thrombin Activates Endogenous CaMKIIδ6 and ERK1/2 in HUVEC

Thrombin-induced endothelial permeability is reported to depend upon Ca2+ signaling (1, 27) and ERK1/2 signaling (16, 17). Moreover, ERK1/2 activation in endothelial cells has been reported to be downstream of Ca2+ signals and mediated by activation of CaMKII (16, 17). However, Ca2+ signals in HUVECs in response to low and high concentrations of thrombin were observed to be markedly different, with low concentrations eliciting repetitive Ca2+ transients and high concentrations of thrombin producing sustained increases in free intracellular Ca2+ (supplemental data S3). These data suggested that the kinetics and/or extent of CaMKII and therefore ERK1/2 activation in response to thrombin might vary as function of thrombin concentration. Activation of endogenous CaMKII and ERK1/2 were assessed by measuring Western blot signals of phospho-Thr287 CaMKII and phospho-Tyr44/42 ERK1/2 (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly (given the distinct differences in patterns of Ca2+ signals), both low and high concentrations of thrombin stimulated comparable transient increases in CaMKII activation, although the kinetics were different with CaMKII activation peaking earlier (0.5 min) following addition of high concentration compared with low concentration (1 min) thrombin (Fig. 3B). ERK1/2 activation lagged CaMKII activation with a gradual increase over the 5-min period studied. However, there was no significant difference in the extent of ERK1/2 activation between thrombin concentrations (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that CaMKIIδ6 and ERK1/2 are maximally activated in response to a low concentration of thrombin which induces only submaximal changes in HUVEC permeability.

FIGURE 3.

Thrombin-induced CaMKIIδ6 and ERK1/2 activation in HUVEC. A, 3-day confluent HUVEC monolayers were serum starved for 4 h and treated with low concentration (2.5 nm) or high concentration (50 nm) of thrombin. Endogenous activated CaMKII was assessed by autophosphorylation on residue Thr287 as detected by immunoblotting with a phospho-Thr287-specific antibody (top panels, pCaMKII) and endogenous activated ERK1/2 was detected with a phospho-ERK specific antibody (middle panels, pERK). β-Actin loading controls are shown in the lower panels. Blots are representative of n = 5 independent experiments. B, densitometric quantification of pCaMKII immunoblots. pCaMKII signals were normalized to β-actin signal to account for variability in loading and expressed as fold increases of the control prestimulus signals. C, densitometric quantification of pERK1/2 signals. pERK1/2 signals were normalized to β-actin signals and expressed as fold increases of control prestimulus signals. Data in B and C are mean ± S.E. from five independent experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05 compared with no thrombin stimulus. n.s. reflects no statistically significant difference between indicated groups.

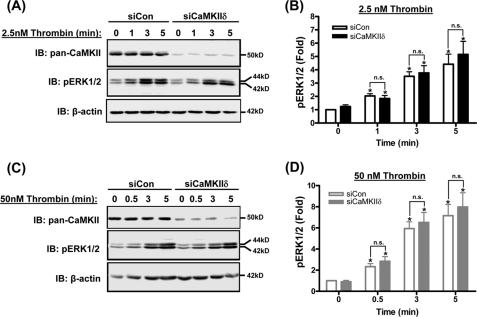

Thrombin Stimulates CaMKIIδ-independent ERK1/2 Activation and ERK1/2-independent HUVEC Hyperpermeability

Because the endogenous CaMKII autophosphorylation in HUVECs preceded ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3), consistent with a previously reported model of CaMKII coupling to ERK1/2 activation in endothelial and other cell types (10, 12, 17, 26), we tested the effects of CaMKIIδ silencing on ERK1/2 activation by thrombin. Unexpectedly, siRNA silencing of CaMKIIδ in HUVECs had no effect on ERK1/2 activation in response to either low concentration (Fig. 4, A and B) or high concentration (Fig. 4, C and D) thrombin. These data clearly indicate CaMKIIδ and ERK1/2 activation are not coupled in HUVECs and may be acting independently to regulate endothelial permeability.

FIGURE 4.

Thrombin induces CaMKIIδ-independent ERK1/2 activation in HUVEC. Representative immunoblots of CaMKII (IB: pan-CaMKII) and activated, phosphorylated ERK1/2 (IB: pERK1/2) in lysates of HUVECs treated with siRNA targeting CaMKIIδ (siCaMKIIδ) or scrambled control siRNA (siCon) and in response to 2.5 nm (A) and 50 nm (C) Thrombin. B and D, densitometric quantification of immunoblots using β-actin signals to normalize for loading and expressed as fold change compared with untreated siCon. Values are means ± S.E., n = three independent experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05 compared with no thrombin (0 min) within each siRNA group. n.s., not statistically significant between siRNA groups.

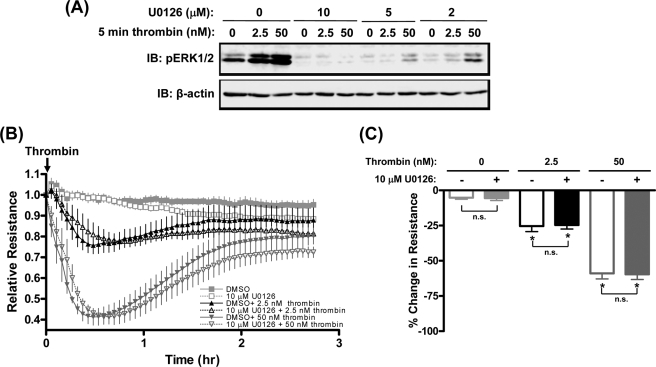

To evaluate the contribution of ERK1/2 signaling pathways to thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability, monolayers were pretreated with 2–10 μm U1026, a selective MEK1/2 inhibitor (28). Fig. 5A shows that thrombin-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was markedly inhibited by pretreatment with U1026 in a dose-dependent manner with complete inhibition after treatment with 10 μm U1026. However, preincubation with the maximally effective concentration of U0126 (10 μm) failed to inhibit either low or high concentration thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability (Fig. 5, B and C). These findings indicate that ERK1/2 activation is not coupled to regulation of thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability.

FIGURE 5.

Thrombin induces ERK1/2-independent HUVEC hyperpermeability. A, immunoblot of activated ERK1/2 (IB: pERK1/2) in lysates from thrombin-stimulated HUVECs for 5 min following 30-min pretreatment with 0–10 μm of the MEK inhibitor U0126. B, effects of 10 μm U0126 or vehicle control (DMSO) on HUVEC monolayer resistance following stimulation with 2.5 and 50 nm thrombin. Symbols and ticks indicate the mean and S.E. of relative resistance from four independent experiments, respectively. C, quantification of maximal changes in monolayer resistance from experiments shown in B. Peak % changes is relative to baselines prior to addition of thrombin. Data values are means ± S.E. from four independent experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05 effects of thrombin on HUVEC resistance compared with vehicle controls; n.s., not significantly different between U0126-treated and vehicle control groups.

CaMKIIδ Mediates Thrombin-induced HUVEC Hyperpermeability through RhoA/Rho Kinase Signaling Pathways

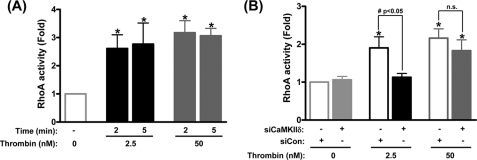

The studies thus far indicate that there are alternative (to ERK1/2) downstream targets for CaMKII in mediating thrombin-induced hyperpermeability. Thrombin-induced RhoA activity has been reported to be important for human endothelial permeability and at least partially dependent on Ca2+ entry (27). A primary target and mediator of RhoA signaling in a number of systems is Rho kinase (ROCK), which has been previously established as a major regulator of endothelial permeability (27, 29). Because it has been reported that Ca2+-induced RhoA activation requires a basal activity of CaMKIIα in neurons (30), we hypothesized a role for the endogenous CaMKIIδ in coupling Ca2+ signals to RhoA activation in HUVECs.

To test this, siCaMKIIδ was used to suppress expression of HUVEC CaMKII and the effect on thrombin-induced RhoA activation was determined (Fig. 6). Like the CaMKIIδ and ERK1/2 activation responses, levels of RhoA activation were comparable in response to both low and high concentration thrombin (Fig. 6A). Silencing CaMKIIδ expression with siRNA strongly inhibited RhoA activation by 40.7% in response to low concentration thrombin, but had no significant effect on high concentration thrombin (Fig. 6B). These data indicate a positive role of CaMKIIδ in mediating low concentration thrombin-induced RhoA activation, with recruitment of non-CaMKII-dependent pathways in response to higher levels of thrombin stimulation concentration thrombin-induced RhoA activation.

FIGURE 6.

CaMKIIδ mediates low concentration thrombin-induced RhoA activation. A, RhoA activation (G-LISA RhoA activity, Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO) in HUVEC monolayers in response to 2.5 nm and 50 nm addition of thrombin for the indicated times. RhoA activity is expressed as fold changes relative to untreated controls. B, effect of siRNAs targeting CaMKIIδ (siCaMKIIδ) on thrombin stimulated RhoA activation. Control cells without siCaMKIIδ were treated with scrambled control siRNA (siCon). Data values are means ± S.E. from five independent experiments. *, p ≤ 0.05 effects of thrombin on RhoA activity; #, p ≤ 0.05 compared between siRNA groups; n.s., no significant differences.

Preincubation with Y27632 (1–5 μm), a well established ROCK inhibitor (28, 29), resulted in concentration-dependent inhibition of thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability confirming this function of ROCK (supplemental data S4). 5 μm Y27632 almost completely abolished low concentration thrombin-induced hyperpermeability but only partially inhibited responses to high concentration thrombin, suggesting recruitment of ROCK-independent pathways with increasing concentrations of thrombin.

DISCUSSION

Thrombin, as a vasoactive mediator, has long been known to increase both endothelial [Ca2+]i and endothelial permeability in vivo (5, 6) and in vitro (1, 27). How the downstream effectors of Ca2+ fit into current paradigms of endothelial permeability mechanisms is still unclear. In this study, we tested regulation of thrombin-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction by CaMKII, a direct downstream effector of intracellular Ca2+ signals, as well as ERK1/2 and RhoA, two indirect effectors of Ca2+ signals, previously implicated as mediators of thrombin-induced endothelial permeability.

For the first time, we defined the predominant endogenous CaMKII isoform in HUVEC and several other primary endothelial cell lines as the CaMKIIδ6 isoform, identical to the δ2 isoform primarily expressed in cultured VSM but lacking an alternatively spliced 21-amino acid C-terminal (6, 11, 12, 14, 15). Limited CaMKII δ6 expression has been reported in mouse gastric mucosal cells (31), but to the best of our knowledge, endothelial cells are the first identified cell type where the δ6 isoform is the predominant endogenous CaMKII. The immediate significance of this observation was that it allowed us to rationally target the bulk of endogenous HUVEC CaMKII with δ-isoform specific siRNA silencing approaches. Importantly, small amounts of δ2 and γb isoforms were detected by RT-PCR and Western blotting with subtype-specific antibodies and our studies do not rule out their potential functional significance from the standpoint of CaMKII holoenzyme subcellular targeting or specific protein interactions.

CaMKII is one of several upstream signaling pathways known to converge on mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability (32). Consistent with earlier reports suggesting a dependence of thrombin-induced EC permeability on CaMKII (16, 17), we documented thrombin-induced activation of CaMKII in HUVECs, inferred by assessing autophosphorylation on Thr287. Thr287 autophosphorylation is known to be a result of Ca2+/CaM-dependent activation of individual kinase subunits and intersubunit phosphorylation within the large CaMKII holoenzyme (15, 21, 26). Surprisingly, the extent and kinetics of CaMKII activation were not markedly dependent upon thrombin concentration over the range used and activation appeared maximal in response to the lowest concentration tested. Functional coupling of this signal to increases in permeability, as determined by siRNA mediated suppression of CaMKIIδ, was only significant in response to low concentrations of thrombin, inferring recruitment of alternative CaMKII-independent pathways by increasing concentrations of thrombin. While it is difficult to judge how the concentrations of commercial thrombin used in our in vitro experiments relate to physiological and pathophysiological relevant thrombin concentrations in vivo, thrombin concentrations reported in blood plasma following venipuncture (0.08–2.4 nm) are in the low range of concentrations used in the present study (33, 34). Thus, the selective function of a CaMKIIδ6-mediated pathway in response to 2.5 nm thrombin could be significant under physiological or pathophysiological conditions of thrombin stimulation. Although it remains to be tested, other Ca2+-dependent endothelial cell stimuli may also be found to be partially or fully dependent upon this signaling pathway.

Given the reported dependence of endothelial cell permeability on ERK1/2 activation (16, 17), as well as our and others previous studies indicating ERK1/2 activation as a point of convergence of multiple proximal signaling pathways, including CaMKII in other cell systems (10, 12, 26), CaMKII-dependent ERK1/2 activation was logically proposed to contribute to thrombin-induced HUVEC hyperpermeability. However, our results clearly demonstrate independent activation of CaMKII and ERK1/2 in response to thrombin in HUVEC. This is in marked contrast to our previous studies using cultured vascular smooth muscle where Ca2+ stimulus-dependent ERK1/2 activation is partially CaMKII δ2-dependent (12, 26, 35). To the extent that the alternatively spliced 21-amino acid C terminus present in the δ2 but not the δ6 isoform may result in specific CaMKII targeting or function, that specificity would not be a property of the kinase expressed in endothelial cells and may explain the difference in coupling of Ca2+ signals to ERK1/2 activation in the two cell types.

Borbiev et al. (17) previously reported that the CaMKII-selective inhibitor KN-93 inhibited ERK1/2 activation in response to thrombin and over-expression of constitutively active CaMKIIα increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in BAEC, suggesting a role for CaMKII in regulating endothelial ERK1/2 activation. Although the reasons for the differences between the results in that study and the current results are not known, there are reported non-selective effects of KN-62 and KN-93 on other CaM kinases, including CaMKIV (36), and nonspecific inhibitory effects of these drugs on membrane ion channel activities (37). In addition, overexpression of a constitutively active or wild-type multifunctional protein kinase, especially an isoform (CaMKIIα) not endogenously expressed, could result in nonspecific activation of signaling pathways due to loss of temporal and spatial control of activity. We believe that the molecular loss-of-function approach used here is a more conservative and specific approach targeting the predominant endogenous endothelial CaMKII δ isoform, and our results effectively rule out involvement of this specific isoform in regulating ERK1/2 in HUVECs. However, we cannot yet formally exclude the possibility that an alternative weakly expressed CaMKII isoform, such as CaMKIIγb, which is detectable in HUVECs, could potentially mediate thrombin-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Both ERK1/2 and ROCK have been reported to mediate thrombin-induced actin cytoskeleton rearrangement in endothelial cells and contribute to increases in monolayer permeability in response to thrombin (17, 38). However, in our studies the widely used and effective ERK1/2 activation inhibitor, U0126, had no effects on thrombin-induced HUVEC permeability. The differences in ERK1/2 dependence reported here might be due to variability across endothelial cell types with respect to the relative importance of various thrombin-induced signaling pathways. For example, Cai and Garcia (32) proposed that ERK1/2 might play a major role in microvascular endothelium and a minor role in macrovascular endothelial cells.

A recent study reported that thrombin-induced Ca2+ entry causes RhoA/ROCK activation leading to increases of human endothelial cell permeability (27). However, the downstream effectors of Ca2+ signals, which lead to activation of RhoA/ROCK signaling were not identified in that study. Our results indicate a role for endogenous CaMKIIδ6 in regulating thrombin-induced RhoA activation. This function of CaMKIIδ6 was also thrombin concentration-dependent with additional non-CaMKII-dependent pathways leading to RhoA activation recruited with higher levels of thrombin stimulation. This scenario is consistent with previous studies showing high thrombin concentration-induced RhoA activation which was only partially calcium-dependent (27). Based on sensitivity to the ROCK inhibitor Y27632, our data confirm ROCK as a downstream mediator of thrombin signaling leading to increases in HUVEC permeability. While low concentration thrombin-induced increases in HUVEC permeability were almost completely abolished by as little as 1 μm Y27632, permeability in response to high concentration thrombin was only partially inhibited by 5 μm Y27632. This suggested that there might be additional RhoA/ROCK-independent pathways culminating in increased permeability that are activated as a function of increasing concentration of thrombin.

Downstream targets of RhoA/ROCK signaling were not evaluated in the present studies. However, there are numerous studies implicating likely cytoskeletal targets which could affect endothelial cell mechanics, cell/cell interactions and ultimately monolayer integrity. Possibilities include RhoA-dependent regulation of actin filament dynamics (39), focal adhesions (40), and adherens or tight junctions (41). It would be interesting to determine if CaMKIIδ6-dependent activation of RhoA selectively contributed to the regulation of one or more of these likely cytoskeletal targets in a thrombin-concentration dependent manner. Given this possibility and the observation that less than a third of individual cells from one confluent HUVEC monolayer displayed Ca2+ responses upon low concentration thrombin stimulation (supplemental data S3), an important consideration in future experiments will be potential localization of CaMKIIδ6/RhoA signaling in a subset of endothelial cells and in discrete subcellular compartments.

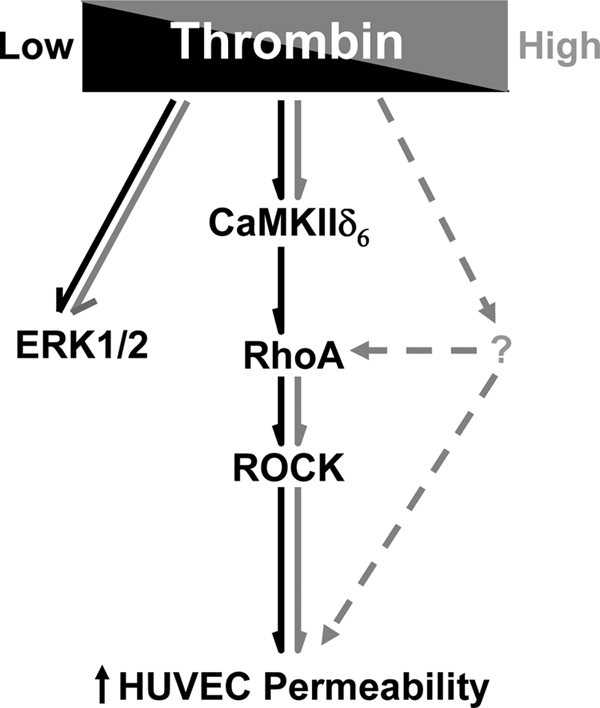

Taken together, the present studies provide a new perspective on thrombin-induced endothelial barrier function that is summarized in a model depicted in Fig. 7. The key findings are: 1) a function for the CaMKIIδ6 isoform in mediating thrombin-induced increases in endothelial barrier permeability, dependent upon the level of thrombin stimulation; 2) the CaMKIIδ6-dependent pathway mediating HUVEC permeability involves downstream activation of RhoA and consequently ROCK; 3) redundant CaMKIIδ6-independent pathways recruited by increasing concentrations of thrombin resulting in Rho/ROCK activation; 4) RhoA/ROCK-independent pathways leading to thrombin-induced endothelial permeability may be recruited by increasing levels of thrombin stimulation; and 5) ERK1/2 activation in response to thrombin in HUVEC independent of CaMKIIδ6 and not involved in regulating thrombin-induced increases in permeability. Stimulus-dependent complexities in endothelial signaling should be kept in mind when designing and interpreting permeability experiments in vitro and when designing inhibitory approaches to attenuate endothelial barrier dysfunction in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

Model depicting signaling intermediates in response to thrombin stimulation leading to increases in HUVEC permeability (hyperpermeability or barrier dysfunction). Dark arrows reflect pathways observed in response to low concentration (2.5 nm) thrombin, and light arrows in response to high concentration (50 nm) thrombin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dee Van Riper and Edward Lewis for production and purification of pCaMKII antibody, Ginny Foster for the technical assistance for cell culture, and Wendy Vienneau for administrative support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL-049426 (to H. A. S.) and RO1 HL-077870 (to P. A. V.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental data S1–S4.

- CaMKII

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- ECIS

- electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing

- VSM

- vascular smooth muscle

- TEER

- transendothelial electric resistance

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ROCK

- RhoA/Rho kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sandoval R., Malik A. B., Naqvi T., Mehta D., Tiruppathi C. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 280, L239–L247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiruppathi C., Ahmmed G. U., Vogel S. M., Malik A. B. (2006) Microcirculation 13, 693–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Trebak M. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 1289–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cioffi D. L., Lowe K., Alvarez D. F., Barry C., Stevens T. (2009) Antioxid. Redox. Signal 11, 765–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaumer L. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiruppathi C., Freichel M., Vogel S. M., Paria B. C., Mehta D., Flockerzi V., Malik A. B. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderling T. R., Stull J. T. (2001) Chem. Rev. 101, 2341–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudmon A., Schulman H. (2002) Biochem. J. 364, 593–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayer K. U., Schulman H. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 917–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rokolya A., Singer H. A. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278, C537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfleiderer P. J., Lu K. K., Crow M. T., Keller R. S., Singer H. A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu K. K., Armstrong S. E., Ginnan R., Singer H. A. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 289, C1343–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.House S. J., Singer H. A. (2008) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.House S. J., Ginnan R. G., Armstrong S. E., Singer H. A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C2276–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercure M. Z., Ginnan R., Singer H. A. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C1465–C1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borbiev T., Verin A. D., Shi S., Liu F., Garcia J. G. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 280, L983–L990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borbiev T., Verin A. D., Birukova A., Liu F., Crow M. T., Garcia J. G. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 285, L43–L54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobimatsu T., Fujisawa H. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 17907–17912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schworer C. M., Rothblum L. I., Thekkumkara T. J., Singer H. A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 14443–14449 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geisterfer A. A., Peach M. J., Owens G. K. (1988) Circ. Res. 62, 749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Riper D. A., Schworer C. M., Singer H. A. (2000) Mol. Cell Biochem. 213, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer H. A., Benscoter H. A., Schworer C. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9393–9400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giaever I., Keese C. R. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 7896–7900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer P., Möhlig M., Idlibe D., Pfeiffer A. (1995) Basic Res. Cardiol. 90, 372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer P., Möhlig M., Schatz H., Pfeiffer A. (1994) Biochem. J. 298, 757–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginnan R., Singer H. A. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C754–C761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavard J., Gutkind J. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29888–29896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies S. P., Reddy H., Caivano M., Cohen P. (2000) Biochem. J. 351, 95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clements R. T., Minnear F. L., Singer H. A., Keller R. S., Vincent P. A. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 288, L294–L306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin M., Guan C. B., Jiang Y. A., Chen G., Zhao C. T., Cui K., Song Y. Q., Wu C. P., Poo M. M., Yuan X. B. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 2338–2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chew C. S., Chen X., Zhang H., Berg E. A. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 295, G1159–G1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai H., Liu D., Garcia J. G. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 77, 30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shuman M. A., Levine S. P. (1978) J. Clin. Invest. 61, 1102–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuman M. A., Majerus P. W. (1976) J. Clin. Invest. 58, 1249–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham S. T., Benscoter H., Schworer C. M., Singer H. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2506–2513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao L., Blair L. A., Marshall J. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345, 1606–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rezazadeh S., Claydon T. W., Fedida D. (2006) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 317, 292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birukova A. A., Smurova K., Birukov K. G., Kaibuchi K., Garcia J. G., Verin A. D. (2004) Microvasc. Res. 67, 64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wójciak-Stothard B., Potempa S., Eichholtz T., Ridley A. J. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 1343–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Nieuw Amerongen G. P., Natarajan K., Yin G., Hoefen R. J., Osawa M., Haendeler J., Ridley A. J., Fujiwara K., van Hinsbergh V. W., Berk B. C. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1041–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiasson C. M., Wittich K. B., Vincent P. A., Faundez V., Kowalczyk A. P. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1970–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.