Abstract

The reductive carboxylation of ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru5P) by 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH) from Candida utilis was investigated using kinetic isotope effects. The intrinsic isotope effect for proton abstraction from Ru5P was found at 4.9 from deuterium isotope effects on V and V/K and from tritium isotope effects on V/K. The presence of 6-phosphogluconate (6PG) in the assay mixture changes the magnitude of the observed isotope effects. In the absence of 6PG D(V/K) and D(V) are 1.68 and 2.46, respectively, whereas the presence of 6PG increases D(V/K) to 2.84 and decreases D(V) to 1.38. A similar increase of T(V/K) is observed as 6PG builds up in the reaction mixture. These data indicate that in the absence of 6PG, a slow step, which precedes the chemical process, is rate-limiting for the reaction, whereas in the presence of 6PG, the rate-limiting step follows the isotope-sensitive step. Kinetic analysis of reductive carboxylation shows that 6PG at low concentrations decreases the Km of Ru5P, whereas at higher concentrations, the usual competitive pattern is observed. These data indicate that full activity of 6PGDH is achieved when one subunit carries out the catalysis and the other subunit carries an unreacted 6PG. Thus, 6PG is like an allosteric activator of 6PGDH.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Cooperativity, Enzyme Catalysis, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Mechanisms, Enzymes, Isotope Effects, Isotope Exchange, Pentose Pathway, 6-Phosphogluconate Dehydrogenase

Introduction

6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGDH)2 catalyzes the reversible oxidative decarboxylation of 6-phosphogluconate (6PG) to ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru5P) and CO2. The enzyme from Candida utilis is a dimer with identical subunits that strictly requires NADP+, and the reduced coenzyme has also been shown to have a nonredox role (1, 2).

The catalytic mechanism of 6PGDH has been widely investigated. The enzyme follows a rapid equilibrium bi-ter sequential mechanism, with a random order of substrate addition both in the direct reaction, oxidative decarboxylation, and, in the reverse reaction, reductive carboxylation (3).

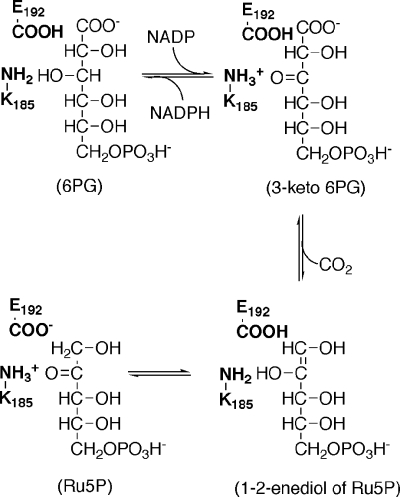

The chemistry of the reaction can be described as a three-step mechanism (Scheme 1). The first step is the oxidation of 6PG to a 3-keto intermediate, the second step is the decarboxylation of the intermediate to the dienol form of Ru5P, and the last step is the conversion of dienol to Ru5P. The catalytic residues were identified by inspecting the three-dimensional structure (4) and by site-specific mutagenesis (5, 6) of the sheep liver enzyme. A conserved lysine (Lys183 in the sheep enzyme) is the acid/base group that accepts an H+ in the dehydrogenation and enolization steps and donates an H+ in the decarboxylation step. A conserved glutammic acid (Glu190 in the sheep enzyme) is the acid that donates an H+ at C1 of the dienol form of Ru5P at the enolization step.

SCHEME 1.

6PGDH-catalyzed reaction and the two main amino acid residues involved.

2H and 13C isotope effects have shown that both dehydrogenation and decarboxylation steps are partially rate-limiting, whereas solvent isotope effects have highlighted a kinetically significant isomerization step preceding dehydrogenation (7–9). This isomerization could correlate with previously reported data supporting a “half of the sites” mechanism in 6PGDH (10).

The least studied step of the reaction catalyzed by 6PGDH was the last step, the conversion of dienol intermediate into Ru5P. The enzyme catalyzes stereospecific keto-enol conversion even in the absence of CO2 (11). It has been shown that this reaction has an absolute requirement of NADPH, which does not have a redox role and can be substituted by nonreducing analogues (1). In kinetic studies, the decarboxylation is assumed to be accompanied by the irreversible release of CO2, so the weight of the last steps in terms of overall kinetics is somewhat shielded. Here, we reported a study of the kinetic isotope effects on the reverse reaction, reductive carboxylation. Our data show that even in the reverse reaction an isomerization step preceding the chemical steps is partially rate-limiting and that 6PG changes the rate-limiting step of the reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

6PGDH from Candida utilis was purified as described previously (12). The specific activity of the purified enzyme was 46 μmol min−1 mg−1. Stereospecifically labeled [1H]-, [2H]-, and [3H]-Ru5P (Ru5P-1-h, Ru5P-1-d, and Ru5P-1-t) were prepared enzymatically from 6PG as described previously (11). Ru5P-1-t was prepared in tritiated water, and the specific activity of purified Ru5P was 55 cpm/nmol. For Ru5P-1-d preparation, buffer was prepared in 99.9% D2O, lyophilized twice to remove exchangeable hydrogen, and redissolved in D2O. The pH (pD) was calculated from a pH meter reading +0.4. The enzymes used in the preparation were precipitated previously by 70% saturated ammonium sulfate, washed twice with 70% saturated ammonium sulfate in D2O, and finally dissolved in the buffer. The isotopic substitution was estimated by NMR and was found to be 94%. Ru5P was purified from the reaction mixture by Dowex 1 ion exchange chromatography and was used within 2 days. Ru5P concentration was determined colorimetrically (13). 1,6-NADPH was prepared by the NaBH4 reduction of NADP+ and purified by DEAE-Sepharose chromatography as reported previously (1).

Isotope Exchange Measurements

Tritium release from Ru5P-1-t was measured as reported previously (1). For tritium uptake measurements, Ru5P-1-h and Ru5P-1-d were dissolved at the desired concentrations in Hepes buffer, pH 6.9, containing tritiated water (specific radioactivity of 9.7 cpm/nmol H+). Contaminating CO2 was removed from the buffer by purging the solution with helium. Enzyme (0.062 mg) and NADPH (0.1 mm) were added, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at 24 °C for 30 min. The samples were then frozen, lyophilized, redissolved in water, and loaded onto a small (cm 0.5 × 4.0) Dowex 1 column. The resin was washed extensively with water to remove any unbound radioactivity, and Ru5P was eluted with 4 × 0.5 ml of NaCl 0.5 m. The eluate was assayed for radioactivity and Ru5P.

Reverse Reaction Measurements

The effect of isotope substitution on Ru5P in reductive carboxylation was measured by comparing the relative reaction rates of Ru5P-1-h and Ru5P-1-d. The reaction was carried out in 0.1 m NaHCO3 saturated with CO2, pH 6.9, 0.15 mm NADPH, and 0.062 mg/ml of 6PGDH by measuring the decrease in NADPH absorbance. The tritium isotope effect was measured in the same NaHCO3 and CO2 buffer, pH 6.9, with 1 mm NADPH, 0.02 mg/ml of 6PGDH, 10 mm isocitrate, and 10 units of isocitrate dehydrogenase. At the desired times, 0.1-ml samples were withdrawn from the reaction mixture, diluted to 0.5 ml, and loaded onto a small Dowex 1 column. The column was washed extensively, and Ru5P was eluted with 0.5 m NaCl, assayed, and counted as described above. A blank reaction without 6PGDH was carried out to verify the stability of NADPH at pH 6.9 during the assay time.

Data Treatment

Nonlinear least-square data fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.02) for Windows, GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA).

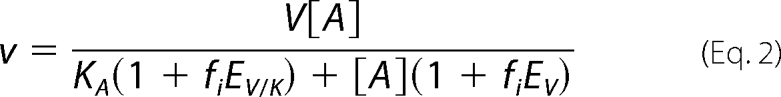

Data were fitted with Equations 1 and 2 for Ru5P-1-h and Ru5P-1-d, respectively,

|

|

where v and V are the initial and maximal velocity, A and KA are the concentration, and the Michaelis constant for Ru5P, fi, is the fraction of deuterium label in the substrate, and EV and EV/K are the isotope effects −1 on V and V/K (14).

Isotope effects are expressed using the nomenclature developed by Cook and Cleland (15). Deuterium and tritium isotope effects are written with a leading superscript D or T, e.g. a primary deuterium isotope effect on V/K is written as D(V/K).

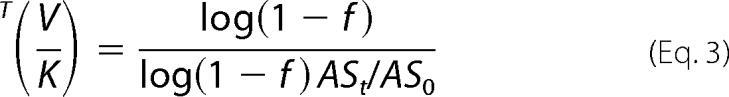

T(V/K) was calculated from Equation 3 at 7.0, 10.2, 23.5, 36.0, 44.1, 56.0, and 64.1% of substrate conversion,

|

where ASt and AS0 are the specific radioactivity at time t and time 0, respectively, and f is the fraction of substrate conversion.

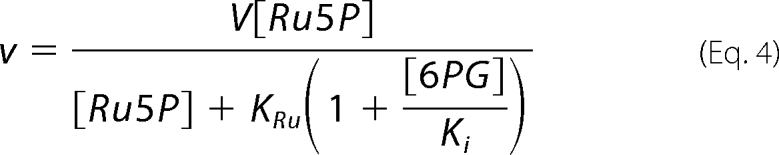

Inhibition of reductive carboxylation by 6PG was determined by fitting Equation 4 for each 6PG concentration.

|

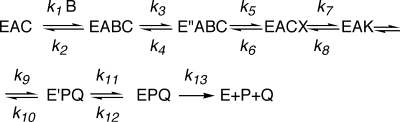

The overall kinetic mechanism is described in Scheme 2, where A is NADPH, B is Ru5P, C is CO2, and P and Q are 6PG and NADP, respectively. X represents the enol form of Ru5P and K represents the 3-keto-6PG. k3/k4 and k11/k12 are isomerization steps.

SCHEME 2.

The overall kinetic mechanism of 6PGDH.

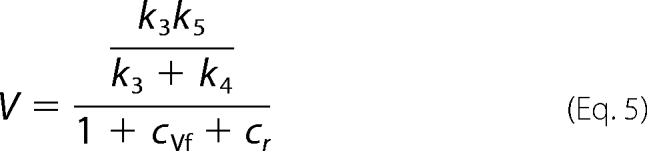

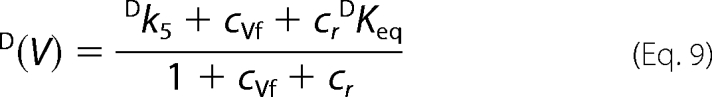

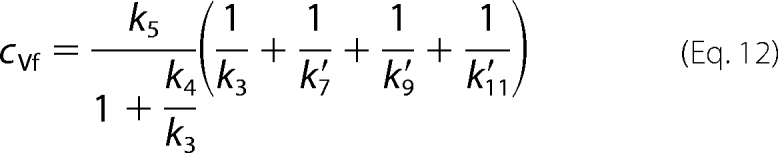

V and V/K are as follows.

|

|

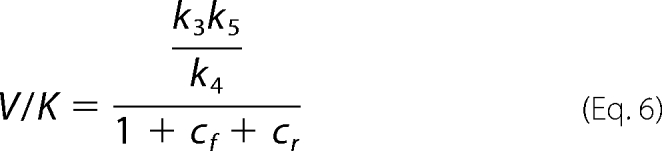

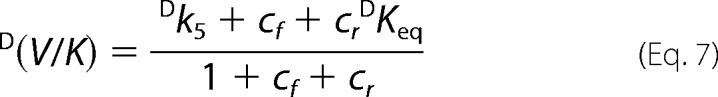

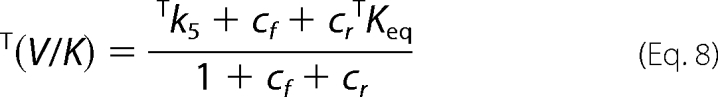

The isotope effects are shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

The terms containing 1/k2 and 1/k13 were not included because the enzyme displays a rapid pre-equilibrium sequential mechanism, and the release of substrate and products is fast. DKeq was assumed to be 0.99 (16).

The intrinsic isotope effect was calculated by setting arbitrary cr values in the following equation.

|

RESULTS

Isotope Effects in Hydrogen Exchange Reaction

The first step of the reductive carboxylation of Ru5P to 6PG catalyzed by 6PGDH is the conversion of Ru5P into dienol, with the release of the proR hydrogen from Ru5P. This reaction requires the presence of NADPH but occurs even in the absence of CO2, and the hydrogen is exchanged with the medium (a so-called tritium exchange reaction) (1, 11). Therefore, we first measured the rate of hydrogen exchange between Ru5P and tritiated water by using Ru5P-1-h and Ru5P-1-d. Both substrates showed the same rate of tritium uptake, resulting in a vH/vD 0.99 ± 0.04. This means that the isotope-sensitive step is not rate-limiting in the tritium exchange reaction. The rate of exchange of Ru5P-1-h, based on the specific radioactivity of tritiated water, was 0.28 ± 0.03 μmol min−1 mg−1. A similar value, 0.27 ± 0.02 μmol min−1 mg−1 was obtained measuring the release of tritium from Ru5P-1-t. These values, measured using a Ru5P concentration of 10-fold Km, are one order of magnitude lower than the rate of tritium release observed during reductive carboxylation (see below). These data suggest that a slow step, which is not present in reductive carboxylation, cancels the isotope effect on proton abstraction from Ru5P.

Effects of CO2 on Hydrogen Exchange Reaction

The carboxylation reaction occurs with the inversion of the Ru5P C1 configuration (11), and it is possible that hydrogen abstraction from Ru5P could require (or could be facilitated by) the presence of CO2. To verify whether CO2 plays a direct role in the first steps of the reaction, we studied the rate of tritium release by Ru5P-1-t in the presence and in the absence of CO2 by using 1,6-NADPH as a coenzyme, which is a nonreducing analogue of NADPH. This analogue can replace natural coenzyme in tritium exchange and in decarboxylation (2, 17) so that the reaction can move up to the 3-keto intermediate. Our experiments show that the presence of CO2 does not modify the rate of tritium exchange, ruling out any role for CO2 in the first step of the reaction.

Reductive Carboxylation

CO2 affinity for 6PGDH is low, ∼50 mm (3), meaning that the rates of reductive carboxylation are measured at nonsaturating CO2 concentrations. To ensure relatively high CO2 concentrations with moderate ionic strength, reductive carboxylation was measured in NaHCO3 saturated with CO2 at pH 6.9.

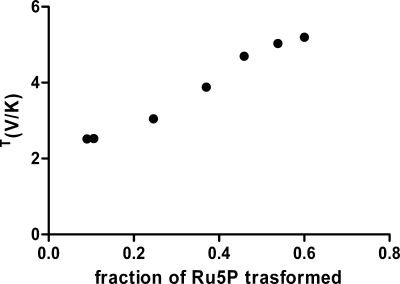

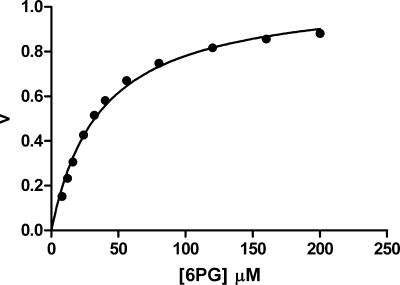

The rate of the reductive carboxylation of Ru5P shows that heavy isotopes slow down the reaction rate. T(V/K) was measured by determining the specific radioactivity of residual Ru5P. At low conversion (<10%), T(V/K) was 2.52; however, T(V/K) calculated from Equation 3 appears to increase by increasing the fraction of Ru5P transformed, reaching 5.2 when the extent of the reaction is >50% (Fig. 1). The only change that occurs during the measurements is the accumulation of 6PG in the reaction mixture. This suggests that the presence of significant amounts of 6PG might change some rate-limiting steps, either by decreasing the commitment factors or by decreasing the rate of the isotope-sensitive step. For this reason, the deuterium isotope effects were measured both in the absence and in the presence of 6PG.

FIGURE 1.

Dependence of the calculated tritium isotope effect on the extent of the reaction. T(V/K) was calculated from the change in Ru5P specific activity at different conversion grades from Ru5P to 6PG (Equation 3).

The isotope effects on V and V/K are different and, in the absence of 6PG, D(V/K) is lower than D(V). (Table 1). The reductive carboxylation rate with Ru5P-1-h and Ru5P-1-d was measured at different CO2 concentrations. Despite the large error, due to few data points, a limiting value D(V) 3.7 ± 0.7 was found.

TABLE 1.

Deuterium and tritium isotope effects on the reductive carboxylation of Ru5P by 6PGDH

D(V) and D(V/K) are the deuterium (D) isotope effects on V and V/K in the presence and in the absence of 6PG.

| Isotope effect | −6PG | +6PG |

|---|---|---|

| D(V) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 1.38 ± 0.16a |

| D(V/K)Ru5P | 1.68 ± 0.13 | 2.84 ± 0.21 |

| T(V/K)Ru5P | 2.55 ± 0.22b | 5.2 ± 0.38c |

a The reported isotope effect was measured at 30.0 mm CO2.

b T(V/K) are the tritium isotope effects at low substrate conversion.

c T(V/K) are the tritium isotope effects at high substrate conversion.

In the presence of 6PG, at 30 mm CO2, D(V/K) increases from 1.68 to 2.84, and D(V) decreases from 2.46 to 1.38. The change in D(V/K) confirms that the observed change in T(V/K) is due to an accumulation of 6PG in the reaction mixture. Efforts to measure D(V) dependence on CO2 concentrations were unsuccessful because the data are scattered, probably due to the combined inhibitory activating effects of 6PG (see below). The changes induced by 6PG on both D(V/K) and D(V) suggest a shift in the rate-limiting step from the early to late steps of the reaction.

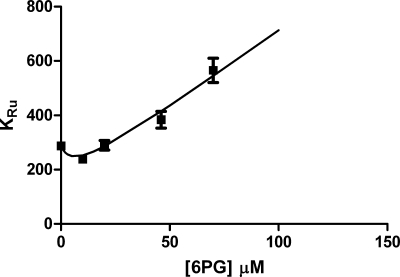

To verify how 6PG affects the kinetic mechanism of 6PGDH, the rate of reductive carboxylation was investigated in the presence of different 6PG concentrations. 6PG is reported to be a competitive inhibitor toward Ru5P (3); thus, Vmax should be constant, and Kapp should increase by increasing the concentrations of 6PG as Kapp = KRu(1 + [6PG]/Ki6PG). Instead, increasing concentrations of 6PG cause anomalous Kapp behavior. For a competitive inhibition, the plot of Kapp against 6PG concentrations is expected to be linear, whereas a biphasic curve is observed (Fig. 2), showing a decrease of Kapp at low 6PG concentrations and the usual competitive pattern at high 6PG concentration. After extrapolation to zero [6PG], the linear part suggests that 6PG could decrease KRu up to 2.4-fold. Also, Vmax appears to be affected by the presence of 6PG; however, the increase is small (<20%) and not statistically significant.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of 6PG on the reductive carboxylation of Ru5P. Effects of 6PG on Kapp, where Kapp = KRu5P(1 + [6PG]/Ki6PG). Squares, experimental points; line: interpolated curve assuming that Ki6PG = 11 μm, KRu5P = 287 μm in the absence of 6PG and 117 μm in the presence of 6PG.

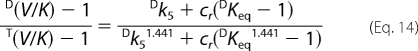

Calculating the Intrinsic Isotope Effect

Taking T(V/K) at low conversion (<10%) as indicative of the tritium isotope effect in the absence of 6PG, and T(V/K) at high conversion as indicative of the tritium isotope effect in the presence of 6PG, we have two sets of three equations (D(V), D(V/K), and T(V/K)). Taking the mean values, for each set of equations, there are four unknown factors (Dk5, cf, cr, and cVf), and estimated Dk5 and commitment factors can be obtained by setting arbitrary values of cr in Equation 14 (Table 2). Both in the absence and in the presence of 6PG, the range of permitted cr values is small, 0 to 0.3 and 0 to 1.1, respectively, and larger values generate negative cVf values (in the absence of 6PG) or cf (in the presence of 6PG). The intrinsic isotope effect for proton abstraction from Ru5P appears unchanged by the presence of 6PG, 4.90–4.92 or 4.93–4.94, and is close to the isotope effect for keto-enol conversion in non enzymatic reactions.

TABLE 2.

Calculated ranges of intrinsic isotope effect and commitment factors

Intrinsic isotope effect and commitment factors are calculated from the average values for D(V), D(V/K) and T(V/K) by setting arbitrary values of cr. Higher values of cr generate negative values for cVf or cf.

| −6PG | +6PG | |

|---|---|---|

| Dk5 | 4.9–4.92 | 4.92–4.94 |

| cf | 4.76–4.43 | 1.14–0.03 |

| cr | 0–0.3 | 0–1.1 |

| cVf | 0.05–0.35 | 8.23–9.37 |

DISCUSSION

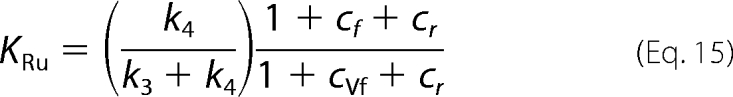

The first concern in the study of the isotope effects on the reverse reaction of 6PGDH is the weight of the isotope exchange reaction that precedes reductive carboxylation. Compared with reductive carboxylation, hydrogen exchange shows a slower rate and the absence of isotope effects. The differences in reaction rate and isotopic effects between the two reactions could be related to the CO2, which is present in the reductive carboxylation but absent in the hydrogen exchange. However, the presence of CO2 does not change the rate of hydrogen exchange, suggesting that the hydrogen ion that comes from the Ru5P is shielded from the solvent. The most surprising result from the measurements of the isotope effects on the reverse reaction catalyzed by 6PGDH is the effect of 6PG on the kinetics of the reaction. In fact, the presence of 6PG, which competes with Ru5P for the same active site, causes a decrease in KRu (Fig. 2). This decrease in KRu is consistent with the calculated values of cf and cVf induced by 6PG. Indeed, KRu is the ratio between V and V/K (Equations 5 and 6),

|

and in the presence of 6PG, cf decreases and cVf increases, resulting in a decrease in the second term of the equation.

The effect of 6PG on the kinetics of the reaction cannot be observed in the forward reaction assays of oxidative decarboxylation, as the forward reaction obviously cannot be studied in the absence of 6PG. Nevertheless, an unexpected 6PG effect has already been reported on the decarboxylation of the 3-keto 2-deoxy 6-phosphogluconate, an analogue of the reaction intermediate 3-keto-6PG. It has been shown that although 6PG at high concentrations in 6PGDH from sheep liver inhibits decarboxylation by competing with the keto intermediate, at low concentrations, it greatly increases the rate of decarboxylation (18). A similar increase in the rate of decarboxylation also has been observed in 6PGDHs from different sources (19). These data indicate that after the dehydrogenation step, the enzyme works more efficiently when one subunit is still occupied by the substrate. This could correlate with the half-site reactivity observed for the coenzyme binding in the ternary complex enzyme-6PG-NADP (10, 20, 21). In fact, if only one NADP is bound to the dimeric enzyme in the ternary complex, a second 6PG could remain unchanged on the second subunit to assist the subsequent reaction steps.

An analysis of isotope effects could help to better understand the role of 6PG in the kinetics of the reaction. A range of values for Dk5, cf, cr, and cVf were obtained (Table 2) from tritium isotope effects at low and high substrate conversion and from deuterium isotope effects.

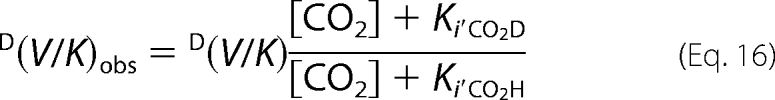

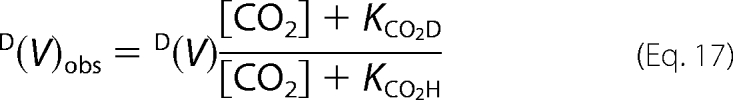

These values are obtained from the isotope effects at 30 mm CO2, but the true values for D(V) should be obtained with all of the reagents at saturating concentrations. If a rapid pre-equilibrium, random ter-bi mechanism holds (3),3 the observed isotope effect on V/KRu5P, at saturating NADPH, is as follows.

|

Ki'CO2 is the dissociation constant of CO2 from the enzyme-NADPH complex and is independent of the isotope substitution on Ru5P, i.e. Ki'CO2H = Ki'CO2D. From the above cited equation, it follows that D(V/K) is independent from the CO2 concentrations.

The observed isotope effect on D(V) at saturating NADPH and Ru5P is as follows,

|

where KCO2 is the Michaelis constant that is dependent on the isotope composition. Thus, the observed isotope effect on V is dependent on the CO2 concentrations. From the above equation, it follows that D(V)obs is comprised within two limiting values: D(V) at infinite CO2, and D(V/K) at 0 CO2. In the absence of 6PG, at 30 mm CO2, D(V)obs > D(V/K) (Table 1), meaning that the true D(V) is higher than that observed. In fact, an approximate value of 3.7 was found. In the presence of 6PG, at 30 mm CO2, D(V)obs < D(V/K), meaning that the true value for D(V) is lower than D(V)obs.

The Dk5 values are calculated by setting arbitrary values of cr (Equation 14) and discharging the values that generate negative values for cf or cVf. The range of permitted cr values in the presence of 6PG is limited by the negative cf values; thus, the estimated values for cr, cf, and Dk5 are still valid. The cVf value is calculated from Equation 9; thus, if D(V) is lower than D(V)obs, the true value for cVf is larger that that reported in Table 2.

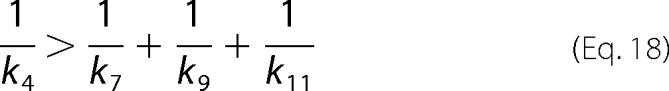

The intrinsic isotope effect in the enolization of Ru5P is lower than the theoretical value of 7–10, suggesting a nonsymmetrical transition state. In the absence of 6PG only cr values <1 and cf values >1 are permitted, meaning that k6 < k7 and that k4 < k5. 6PGDH displays a random bi-ter mechanism with the rapid binding/release of substrates/products (3), so it is unlikely that k4 could be the Ru5P release step. To explain the high cf value, a slow step preceding the isotope-sensitive step has been inserted into the mechanism. This step is likely to be an isomerization of the enzyme-substrate complex, similar to the partially limiting isomerization observed in the forward reaction (9). D(V/K) is smaller than D(V), meaning that cf is greater than cVf, and from the definition of cf and cVf (Equations 10 and 12) it follows that,

|

or, in other words, not only is k4 lower than k5, but it is also lower than all other steps following proton abstraction from Ru5P. Furthermore, k6 < k7, as required by cr < 1, indicates that Ru5P enol-keto conversion is slower than decarboxylation. Taking all of this evidence into account, it appears that the isomerization of the enzyme-Ru5P complex is rate-limiting, and the enolization of Ru5P is partially rate-limiting, resulting in D(V) ≈ 3.7, whereas the intrinsic isotope effect Dk5 is estimated at 4.9. These conclusions conflict with previous observations that the rate-limiting steps of oxidative decarboxylation are the isomerization of the enzyme-6PG complex and, to a lesser extent, dehydrogenation and decarboxylation (9). Thus, evidence from the kinetic isotope effects suggests different rate-limiting steps in the forward and reverse reactions, being contradictory with the principle of microscopic reversibility. However, the contradiction could result from different experimental conditions or, in this case, from some peculiar property of the enzyme that provokes unexpected differences in the forward and reverse reaction assays. A primary difference is the reaction pH. In fact, Rendina et al. (7) measured deuterium and tritium isotope effects on the forward reaction in Hepes, pH 8.0, whereas the reverse reaction is here performed in the HCO3 buffer, pH 6.9. But the greatest difference is that the forward reaction assay is obviously carried out in the presence of 6PG, and the presence of 6PG in the incubation mixture of the reverse reaction causes an increase in D(V/K) and a decrease in D(V). Under these different conditions, cf < cVf; thus, inequality (Equation 18) is reversed. Furthermore, when 6PG is present, the permitted values of cf become < 1, and the isomerization preceding Ru5P enolization is not rate-limiting. Thus, the isomerization, which is the last step preceding Ru5P release into the forward reaction, is not rate-limiting under normal assay conditions for 6PGDH. The increase in cVf simply could be due to an increase in the k3k5/(k3 + k4) ratio, although the wider range of permitted values for cr could suggest a higher weight in the steps following the enolization in determining the rate of the reaction. In other words, in the presence of 6PG, the step(s) following proton abstraction from Ru5P, either the carboxylation, reduction, or isomerization of the enzyme-6PG complex, become rate-limiting, and the principle of microscopic reversibility is satisfied.

For the principle of microscopic reversibility, the 6PG effect on the reverse reaction should find a counterpart in the forward reaction. Therefore, at 6PG concentrations lower than its Kd, when the enzyme is mainly occupied by the substrate with only one subunit, the reaction rate must be lower than that observed when both subunits are occupied by 6PG, one acting as a substrate and the other one as an allosteric effector. This has never been observed, but it is easy to explain how these differences have escaped researchers. In fact, simulation of a cooperative behavior with a 2.4-fold change in Km (as observed in the reverse reaction), shows that in the substrate range from 0.2 to 5 times the apparent Km, the expected data are well fitted with the normal Michaelis-Menten kinetics, with an r2 of 0.9921 (Fig. 3). Otherwise, there is abundant evidence that 6PG modulates 6PGDH activity. In the forward reaction, it suppressed inhibition by NADP and decreases inhibition by NADPH by increasing the Kd of the reduced coenzyme 6-fold (10), it increases the rate of decarboxylation of the 3-keto intermediate (18, 19), whereas in the reverse reaction, it decreases the Km and removes the slow step.

FIGURE 3.

Cooperative versus Michaelian behavior of 6PGDH. Squares, cooperative behavior assuming Km 70 μm and Vmax 1.0 for the dimeric enzyme with one 6PG bound, and Km 44 μm and Vmax 1.0 for the dimeric enzyme with two 6PG bound; line: nonlinear fit according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics giving Vmax 1.01 and Km 38 μm.

The significance of 6PGDH activity modulation by 6PG is unclear; however, an attractive hypothesis can be formulated. 6PG is an inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and an activator of phosphofructokinase (22, 23), and the fine tuning of the steady-state concentrations of 6PG could allow cross-talking between glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway.

The general rate equation for the reductive carboxylation of Ru5P by 6PGDH (3) is v=VABC/(Ki,AKi'BKC + Ki'CKBA + Ki'AKCB + Ki'AKBC + KABC + KCAB + KBAC + ABC), where A is NADPH, B is Ru5P, and C is CO2. Ki, Ki, and K are the dissociation constants from the binary complexes, the dissociation constants from the ternary complexes, and the Michaelis constants, respectively. At saturating NADPH (A) the equation is reduced to: v =VBC/(Ki'CKB + KCB + KBC + BC). For B → 0, v = VBC/[KB(Ki'C + C)] or (V/KB)obs = (V/KB)C/(Ki'C + C). For B → ∞ v = VC/(KC + C) or Vobs = VC/(KC + C).

- 6PGDH

- 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase

- 6PG

- 6-phosphogluconate

- Ru5P

- ribulose-5-phosphate

- Ru5P-1-h

- 1-R-[1H]-Ru5P

- Ru5P-1-d

- 1-R-[2H]-Ru5P

- Ru5P-1-t

- 1-R-[3H]-Ru5P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rippa M., Signorini M., Dallocchio F. (1972) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 48, 764–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rippa M., Signorini M., Dallocchio F. (1973) J. Biol. Chem. 248, 4920–4925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berdis A. J., Cook P. F. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 2036–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams M. J., Ellis G. H., Gover S., Naylor C. E., Phillips C. (1994) Structure 2, 651–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karsten W. E., Chooback L., Cook P. F. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 15691–15697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L., Chooback L., Cook P. F. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 11231–11238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rendina A. R., Hermes J. D., Cleland W. W. (1984) Biochemistry 23, 6257–6262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang C. C., Berdis A. J., Karsten W. E., Cleland W. W., Cook P. F. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 12596–12602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang C. C., Cook P. F. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 15698–15702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallocchio F., Matteuzzi M., Bellini T. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 10778–10780 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lienhard G. E., Rose I. A. (1964) Biochemistry 3, 190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rippa M., Signorini M. (1975) Methods Enzymol. 41, 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dische Z. (1962) Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry 1, 481–482 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L., Dworkowski F. S., Cook P. F. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25568–25576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook P. F., Cleland W. W. (1981) Biochemistry 20, 1790–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleland W. W. (1980) Methods Enzymol. 64, 104–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanau S., Dallocchio F., Rippa M. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1122, 273–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanau S., Dallocchio F., Rippa M. (1993) Biochem. J. 291, 325–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rippa M., Giovannini P. P., Barrett M. P., Dallocchio F., Hanau S. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1429, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanau S., Dallocchio F., Rippa M. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1159, 262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montin K., Cervellati C., Dallocchio F., Hanau S. (2007) FEBS J 274, 6426–6435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noltmann E. A. (1972) The Enzymes (Boyer P. D. ed) 3rd Ed., Vol. 6, pp. 272–354, Academic Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommercorn J., Freedland R. A. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 9424–9428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]