Abstract

We investigated the neural processing underlying own-age versus other-age faces among 5-year-old children and adults, as well as the effect of orientation on face processing. Upright and inverted faces of 5-year-old children, adults, and elderly adults (> 75 years of age) were presented to participants while ERPs and eye tracking patterns were recorded concurrently. We found evidence for an own-age bias in children, as well as for predicted delayed latencies and larger amplitudes for inverted faces, which replicates earlier findings. Finally, we extend recent reports about an expert-sensitive component (P2) to other-race faces to account for similar effects in regard to other-age faces. We conclude that differences in neural activity are strongly related to the amount and quality of experience that participants have with faces of various ages. Effects of orientation are discussed in relation to the holistic hypothesis and recent data that compromises this view.

Keywords: Face recognition, Inversion effect In/Out-group, Own-age bias, Experience

INTRODUCTION

The human face directs the way both children and adults react, adjust, and adapt to social and physiological demands (Harris & Aguirre, 2008), and is perhaps the most important bridge between our biology and our social relationships. It is therefore not surprising that faces are recognized using dedicated circuits in the inferior temporal cortex, i.e., fusiform gyrus (Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, 1997), in the ventral occipito-temporal regions, and also in other regions of the superior temporal sulcus (see Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini 2000 for a review). Although there has been considerable work focused on describing the development of face processing, relatively little work has focused on the mechanisms that underlie development; similarly, there is still debate as to the timing and nature of the experiences that shape the development of the neural architecture that underlies face processing (for discussion, see Nelson, 2001; de Haan, 2008). Nevertheless, it is widely acknowledged that experience does exert considerable influence over how faces are processed.

One experience that children encounter early in life are differences between own-aged individuals and other-aged individuals, a distinction that is important when, for example, preschool groups are constructed, when age-related tasks are presented in kindergarten, and when children start school.

The importance of experience

Experience modulates children’s and adults’ perception of faces along various dimensions and the tuning of the ability to process faces seems to be dependent on the social environment and contact with relevant exemplars. For example, 3-months-old infants show a preference for faces of the same gender as the primary care giver (Quinn et al., 2002). In addition, the other-race effect (for this paper; ORE), which refers to the observation that adults more accurately recognize faces from their own ethnic group, is found to be partially in place as early as 3 months of life (Sangrigoli & de Schonen, 2004). The relative plasticity and specialization of face processing is further demonstrated by studies of different kinds of “expertise” after exposure or intensive training. For example, Korean adults that were adopted by French families between 3-9 years of age recognized photos of French adults similarly to the native French population. In contrast, Korean adults who had moved to France as adults demonstrated the ORE (Sangrigoli et al., 2005). Lastly, evidence from the “other-species effect” (OSE) confirms that extended exposure within a sensitive period (e.g., between 6 and 9 months of age) to faces of other species, precisely to faces of Barbary macaques, may facilitate and endure face discrimination capabilities of such monkey faces that would be otherwise lost during development (Pascalis et al., 2005).

It is unclear if the frequency of contact — experience - is more or less important than the quality of contact (Bernstein et al., 2007; Sporer, 2001). In Sporer’s in-group/out-group model (IOM) of face processing, an attempt to account for the out-group recognition deficit and the more lax response criterion (less conservative) with respect to out-group faces is made. The IOM implies that in-group faces are processed effortlessly in a holistic manner, leading to superior recognition. Subjects will, on the other hand, spend less time attending to out-group faces, which will result in poorer recognition (Sporer, 2001). Along the lines of Sporer’s in-group model, recent empirical evidence illustrates the presence of an additional dimension, age, which influences our perception of faces.

Accordingly, if the IOM applies to own vs. other ages, the own-age effect would be dependent both on a greater perceptual expertise in processing facial features and configurations typical of in-group members (i.e. of same age), and on categorical processing that prevents encoding out-group members’ faces as individuals (Bernstein, Young, & Hugenberg, 2007; Meissner & Brigham, 2001; Sporer, 2001). A question arises of course, as to what degree this is caused by group membership alone, by experience, or by a combination of the two. Contrary to children, adults have been member of the younger age group and shared the same motivational factors, such as social demands from same age individuals, which influence social categorization and may result in biased face processing. Does this make them life-long experts of this group to which they belonged before?

Development of Face Processing

Although there is empirical evidence for a steady improvement in face encoding abilities between infancy and preadolescence. (Chance & Goldstein, 1984; Sangrigoli & de Schonen, 2004; Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004), the effect of experience with own-age faces has not yet been extensively investigated. Intensive exposure to own-age faces may confer privilege to enhanced processing for own-aged faces and imply similar mechanisms as in the ORE and OSE, resulting in preferences for own group target and an own-age bias, or “expertise” (Sporer, 2001; Wright & Stroud, 2002). In particular, much of the prior work on age differences in face recognition has commonly employed faces of college-aged students as targets while comparing other age groups to college-aged participants’ memory for faces (for reviews see Chung & Thompson, 1995; Perfect & Moon, 2005). Thus, the observed differences in children and adults’ processing and mnemonic capacities may be confounded with the stimuli typically used in face studies, resulting in data that are difficult to interpret as to whether the results reflect adults’own-age bias or a genuine superior recognition. Without a control for potential own-age bias, or an experimental design that fully controls for relevant factors, i.e., testing child and adult targets across child and adults participants, conclusions about developmental trajectories in face processing and potential own-age biases cannot be reliably made.

To our knowledge there are only a few published studies that have investigated whether an own-age bias exists in children (Anastasi & Rhodes, 2006; Anastasi & Rhodes, 2005; Chung, 1997). While Chung (1997) did not report any own-age bias for children (but did report an own-age bias for adults) and Anastasi and Rhodes’ (2006) study revealed marginally but non—significant better recognition for own-age targets (p’s ≤ .10), Anastasi and Rhodes (2005) showed an own-age bias for older adults, and an inverted own-age bias for children. Contrary to the theoretical prediction available (Meissner & Brigham, 2001) — that is, more conservative criterion to in-group faces - , Anastasi and Rhodes’ (2005) results showed that children demonstrated less conservative response bias in regard to pictures of children. As discussed by the authors, this effect might have been encouraged by the encoding instruction given to participants (e.g., to estimate the age of the individual in each photo). Additionally, the range of the children’s and the older adults’ age was quite wide (children’s age range = 5-8-years, adults age range = 55-89-years). Finally, as recognized by Kuefner Cassia, Picozzi, and Bricolo, (2008), these studies all rely on the theoretical assumption posed by Sporer (2001) regarding IOM, while in fact the amount of exposure, i.e. the experience hypothesis, may be a more valid starting point when exploring other-age effects..

Recognition of unfamiliar faces undergoes continuous development until adulthood. This leads us to ask precisely what is developing? Most studies of children’s face recognition capabilities have focused on recognition (cf. bias recognition paradigms commonly employed within the ORE and the OSE literature, which effects imply the retrieval phase), and ignored testing specific encoding processes (Anastasi & Rhodes, 2005, 2006). Available data suggests that both encoding and retrieval improve with age, but only encoding is affected by configural manipulations (Itier & Taylor, 2004a). Only one study has, to our knowledge, specifically looked into the own-age effect and its relation to encoding mechanisms exploring the experiential hypothesis (Kuefner et al., 2008). One way to study encoding processes is to manipulate the orientation of faces, such as, the “face inversion effect” (Yin, 1969).

The inversion effect

When a face is inverted, configural (or holistic) processing is disrupted and face perception and recognition are impaired (Farah, Tanaka, & Drain, 1995). Because the orientation of a face is thought to reliably predict different processing strategies (but see Harris & Aguirre, 2008), researchers have employed upright and inverted faces to study configural and featural information processing in adults (Farah, Wilson, Drain, & Tanaka, 1998; Tanaka & Farah, 1993), in children (Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004), and in infants (Webb & Nelson, 2001). A typical finding is that the inversion effect and its corresponding configural or holistic processing is present in young children and infants, as in adults, but the strength of this effect varies across studies and experimental conditions and questions have been raised as to whether this reflects different developmental trajectories of inverted and upright faces. Findings suggest a faster improvement with age in the recognition of inverted faces than with upright faces (Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004). However when working memory was controlled for, Itier and Taylor (2004b) concluded that performance increased in parallel from 8 years of age until adulthood for both upright and inverted faces. Electrophysiological evidence indicates that specific components of the event-related potential (ERP) seem to be affected by inversion at different ages. In particular, re-analyses of three studies suggest that the face-sensitive component, the N170, is influenced by inversion from mid childhood, in contrast to the P1, which seems to be task sensitive from 4 years of age (Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004). Finally, the inversion effect has also been employed in studies of the ORE. Own-race faces are generally viewed as being processed holistically, whereas other-race faces are processed analytically (as features; see Tanaka, Kiefer, & Bukach, 2004). In regard to ERPs, a more negative and delayed N170 was found for other-race faces compared to own-race faces, and the P2 component of other-race face experts (e.g., individuals with extensive experience with the other race) showed a comparable response to other-race faces as to own-race faces over right occipitotemporal regions (Stahl, Wiese, & Schweinberger, 2008).

In summary, we know that gender, species, and race all influence face processing. However, it is unclear to what degree age is an important factor in face processing. If face processing is modulated by own-age experience then we would expect similar activation patterns as has been showed for own-race faces..In regard to own-age, we still need to compare well-defined age groups, employing photos of individuals representing the different ages without any specific instruction that potentially could prime participants to bias response as in the Anastasi and Rhodes’ (2005) work cited above. As discussed, much of the face processing work published has focused on the retrieval phase. In this study we highlight the basic encoding processes of own versus other-age faces employing established paradigms (e.g., the inversion effect and the own versus other principle of testing influence of experience) in a passive viewing approach while controlling for participants’ attention to stimuli by recording eye tracking patterns and ERPs.

The present study

Whereas in-group faces (i.e. of same age) are processed in a holistic manner, leading to superior recognition, subjects process out-group members categorically, which prevents encoding out-group members’ faces as individuals and results in poorer recognition (IOM; Sporer, 2001). There are potential confounds when designing an “other-age” study. Specifically, adults have been members of younger age groups during their life span and have had significant experience and motivation to enable identification and in/out group categorization across several age groups. In this sample, the adult participants were parents of the participating children, which likely had an impact on their current experience with 5-year-old children. This fact makes it difficult to tease apart the contributions of the adults’ current and past experience with children and may potentially influence the results. To control for the amount of current experience, we estimated participants’ experience with own and other-age groups via questionnaires. We also included questions about experience with elderly adults (> 75 years of age), as both adults and children presumably have less contact and experience with such individuals. For the same reason, we included elderly faces as a control in our stimuli material (see fig. 1).

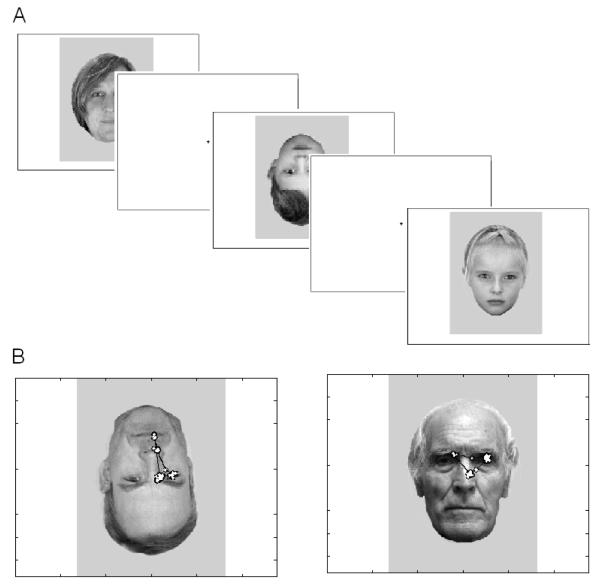

Figure 1.

Panel A shows stimuli flow used in the experiment. Pictures of children, adults, and old adults (15.2 × 10.7 visual degrees) were employed and stimuli were randomly presented up righted and inverted.

Panel B exemplifies typical scanning patterns across participants.

Our prediction related to the manipulation of facial orientation is that upright faces would encourage holistic or configural processing, while processing of inverted faces would disrupt holistic processing and result in slower processing and longer latency as evidenced by ERPs (e.g., longer latency components) (Bentin, Allison, Puce, Perez, & McCarthy, 1996). To evaluate the electrophysiological correlates of face encoding processes, electrodes over the right ventral occipital-temporal cortex around the lateral fusiform gyrus that generates P1 and P2 responses over occipital scalp were analyzed.

Electrophysiological studies using EEG have suggested that face processing activates neural systems in inferior temporal cortex between 140 and 190 ms post-stimulus onset, indexed by the N170 component (Bentin, et al., 1996; George, Evans, Fiori, Davidoff, & Renault, 1996; Taylor, Batty, & Itier, 2004). The N170 may well be used as a reliable neuropsychological correlate of face perception in developmental studies (Itier & Taylor, 2004a, 2004b).

In regard to electrophysiological markers of own-age processing and of the inversion effect, we offer several predictions. Specifically, an enhanced configural processing for own-age targets and for upright faces is expected to produce shorter N170 latencies and to generate smaller N170 amplitudes in adults compared to other-age and inverted faces. We explore whether children follow the same pattern. Because the P1 component shows sensitivity to low-level properties, such as orientation, but not to perceptual expertise, we did not predict any effect in regard to picture content. However, the P1 will be sensitive to orientation and evince slower processing and longer latency for inverted faces compared to upright faces.

For the P2 component, we expected to find smaller P2 amplitudes for own-age faces and for upright faces, however this should vary with experience such that “experts” (e.g., adults to both children and adults) shall evince similar activation to own- and other ages, i.e. their former membership in the child group and/or greater experience will result in abolishing the own-age effect, as it abolished the ORE (cf. Stahl et al., 2008).

METHODS

Participants

Nineteen healthy adults (16 female, M = 35.42 years, SD = 6.33, range = 25-53), all parents to the 19 participating 5-year-old children (9 female, M = 62.63 months, SD = 3.00, range = 59-70) consented in accordance with ethical standards (Helsinki, 1964) to participation1. All had corrected-to-normal vision, were of Scandinavian Caucasian origin, and came from similar urban areas. A brief questionnaire that mapped participants’ experiences with own and other age groups showed that the children had daily interactions with other 5-year-old mates, with their parents, and all except one met their grandparents (e.g., an elderly adult) at least once a month (range = weekly to every other month). Adults saw other adults every day, provided care to their own children on a daily basis, and all except one met with their parents (e.g., an elderly adult) at least once a month (range = weekly to once a year). Based on participants’ responses to our questionnaire, they were included if they a) had daily contact with other in-group members, and b) had considerably less contact with elderly adults. In addition, child and adult participants had daily contact with each other’s age groups (e.g., all adults were parents to 5-year-old children).

Stimuli

Caucasian individuals of each age group (i.e., 5-year-olds (range 49-60 months), 35-45-year old adults, and elderly adults all above 75 years of age) volunteered as models to create a set of neutral faces. The children were recruited from several kindergartens across an urban city, adult models worked within the university system, and old adults were all recruited from different homes for elderly people. The final set of face stimuli consisted of 120 black-and-white high-resolution photographs (40 of each age group, balanced for gender). Hair, facial marks, and jewelery were removed from the photos and pictures were resized to 358 × 432 pixels, (visual angel, vertical = 15.2° × horizontal = 10.7°), inverted by 180 degrees, and a grey background was inserted employing Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (see Fig 1A and 1B). A picture of a teddy bear holding a heart was randomly presented periodically in order to maintain attention for the child participants. These trials were discarded from further processing.

Procedure

Upon arrival at the laboratory, the purpose of the study was explained and informed consent was obtained. Parents monitored their child’s test session from a room adjacent to the test room, where they were also asked to fill out the experience questionnaire. Once the child was comfortably seated, a 128-channel HydroGel Geodesic Sensor Net v 1.0 (Electrical Geodesics, Inc., Eugene, OR) was applied. Participants were asked to look at each of five points on the screen in order to calibrate the Tobii X1750 eye tracker (Tobii, Stockholm, Sweden) used to record participants’ gaze.

Children sat 50 cm from the computer screen and were instructed to fixate the centre of the monitor and to minimize any body movements during the recording period. Subjects were encouraged to blink during the inter-stimulus interval during which time a blank slide was presented. An adult experimenter sat next to the child throughout the session to monitor the child’s attention. If the child became fussy, or moved excessively, the experimenter could pause the study. The experiment consisted of 520 total trials. Each trial included a black fixation cross presented for 900 to 1150 ms, immediately followed by a face on 480 trials (160 presentations each of child, adult, and elderly faces) and a teddy bear on 40 trials. Each face was presented twice upright and twice inverted with stimulus duration of 750 ms (see Fig. 1A). Stimuli appeared centered on a blank screen. In order to maintain attention, participants were instructed to press a button on the response box when a teddy bear appeared on the screen. Stimulus presentation was controlled by a PC running E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc, Pittsburgh, PA), employing full randomization across photo type (e.g., face age and orientation) and participants. At the conclusion of the child’s testing session, a similar testing procedure was employed with the parent participants.

Gaze recording

Gaze was measured using a Tobii 1750 near infrared eye tracker; precision 1, accuracy 0.5, and sampling rate 50 Hz. A standard five point calibration was used. The onset of trials and individual pictures as marked by E-prime and added to both the EEG and eye tracking data stream in real time. The gaze pattern of all trials were checked manually to make sure that only trials were participants watched the face (for at least 200 ms) was included. All trials where participants did not look at the face (gaze outside face by more one visual degree of the face) were removed from further analysis of both gaze and ERP data.

Analysis of gaze calculates how much gaze deviated from the mean gaze fixation, separate on each trial, measuring the distribution of gaze (Grönqvist, Gredebäck, & von Hofsten, 2006) as well as the length of participants’ fixations on each trial. None of these variables did, however, differ between conditions or ages, p’s > .05. Participants gaze was on average fixating the face for 900 ms and gaze remained stable throughout each trial (RMS were well below one visual degree, which is the accuracy of the eye tracker). Both of these measures are only reported for trials that passed the inclusion criteria defined above.

EEG recording

EEG data were collected and processed using NetStation software (Electrical Geodesics, Inc., Eugene, OR). Data were recorded continuously from 128 channels and synchronized with the onset of stimulus presentation and with eye tracking apparatus. Blinks and vertical eye movements were registered by means of electrodes below and above the eyes, and horizontal movements were recorded from electrodes near the outer canthi of the eyes, all integrated in the sensor net. Electrode impedances were considered acceptable if at or below 100 KΩ and Cz served as the reference lead during acquisition. Signals were amplified using EGI NetAmps 300, a highpass filter of 0.3Hz was applied, and data were sampled at 250 Hz. A 30-Hz lowpass filter was applied post-collection, and trials were constructed that consisted of a 100-ms baseline and 800 ms following stimulus onset. Data were baseline corrected to the average voltage during the 100 ms prior to stimulus onset. Channels contaminated with motion artifacts exceeding 80 uV (adults) or 150 uV (children) within a trial period of 800 ms were rejected via computer algorithm. Vertical ocular movements were rejected if amplitude changes of > 150 uV (adults) or 200 uV (children) were detected within the trial period and horizontal eye movements were rejected if amplitude changes exceeding 100 uV (both adults and children) were detected within the trial period. Trials were excluded if more than 12 of the sensors were rejected.

In addition, each trial was analyzed with respect to participants’ gaze and trials where participants did not fixate on the face for a minimum of 200 ms was discarded from both EEG recording and the analysis of gaze data. Of the remaining trials, individual channels containing artifact were replaced using spherical spline interpolation and data were re-referenced to an average reference. Individual subject averages were constructed separately for each face age and orientation.

The final sample consisted of 12 children (50 % female, M age = 63.33 months, SD = 3.26, range = 59-70) and 13 adults (85 % female, M age = 35.54 years, SD = 4.79, range = 25-43). Rejection of data was done in two steps. First, we employed automated algorithms to detect bad channels and trials. Second, we manually edited individual trials for artefacts as follows: Drift over at least 12 channels (noise) that spread to other channels, or undetected eye movements or blinks. In addition, 2 of the adult participants were taken out because we did not succeed in recording their eye movement fully integrated, which was a goal to do with all included participants. ERP components were labeled according to polarity-latency convention and quantified by measuring the maximum peak amplitude and latency to peak amplitude. Inspection of the grand averaged waveforms revealed three well-defined components of interest that were subsequently analyzed within the following time windows: P1 (child = 80-168 ms, adult = 52-120 ms), N170 (child =168-300 ms, adult =108-180 ms), and P2 (child = 260-388 ms, adult = 164-252 ms). As face-sensitive components are most prominent at occipitotemporal and parietal sites (Stahl, Wiese, & Schweinberger, 2008; Itier & Taylor, 2004), we created regions of interest (ROIs) by averaging over these particular arrays of electrodes (see Fig. 2). Numerous studies have shown that these components are maximal over right hemisphere therefore differences in scalp topography were not examined.ERP amplitudes and latencies were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with participant age as a between subjects factor (5-year-old children vs. adults), and face age (5-year-old children vs. adults vs., elderly adults), and orientation (upright vs., inverted) as within subjects factors. Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom and adjustments for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni) were used.

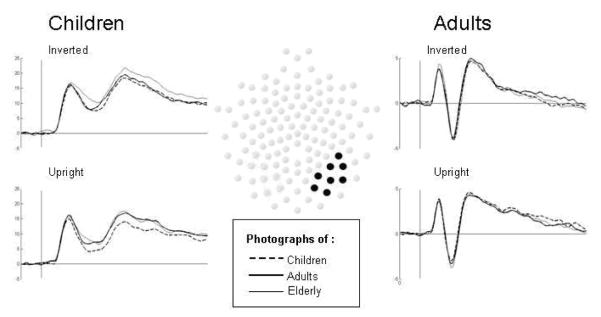

Figure 2.

Middle; particular arrays of electrodes employed to create ROI. Left; children’s grand averaged ERP’s by condition. Right; adults grand averaged ERP’s by condition.

RESULTS

Electrophysiology

Grand-averaged ERPs of the three components (e.g., P1, N170, and P2) are shown for both age groups and conditions in Fig. 2, left and right panel. Note that the maximum and minimum amplitudes shown in the table do not correspond exactly to the minimum and maximum values in the graphed grand averages because the values are computed in slightly different ways.

P1 Component

Amplitude

Inverted faces elicited larger amplitudes (M = 11.00 μV, SD = 7.93) than upright faces (M = 10.40 μV, SD = 8.04), F(1,23) = 6.75, p =.02, η2 = .23, and orientation did not interact with participant age. Although not hypothesized, a main effect of face age, F(1,23) = 4.19, p <.02, η2 = .15, was further evinced. Pairwise comparisons showed that children’s faces (M = 10.30 μV, SD = 7.66) elicited the smallest amplitudes and significantly differed from elderly faces (M = 11.13 μV, SD = 8.35), F(2,48) = 3.74, p =.03, but not from adult faces (M = 10.64 μV, SD = 8.00). Faces of adult and elderly did not differ.

Latency

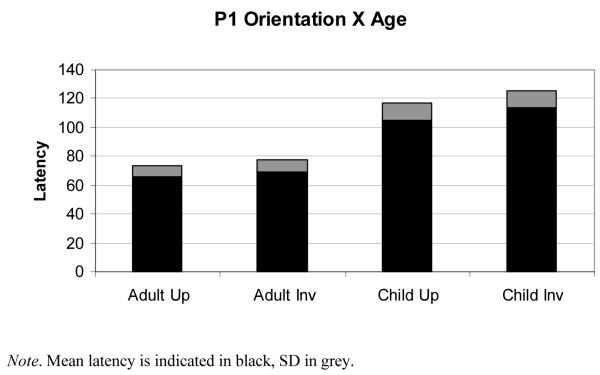

It was further predicted that shorter P1 latencies would be observed to upright faces compared to inverted faces. First, we detected a main effect of orientation in the predicted direction, F(1,23) = 39.59, p <.001, η2 = .63. However, as can be seen in Fig. 3, an interaction between orientation and participant age demonstrated that processes underlying inversion effects are strongly related to age, F(1,23) = 10.18, p <.001, η2 =.31. Children as a whole have significantly longer latencies to both upright and inverted faces, and have larger latency differences between upright and inverted faces than adults.

Figure 3.

Plot shows the interaction between orientation of picture and age of participants in the Latency P1 component.

Thus, orientation did not interact with participant age when amplitude measures were analyzed. However, orientation did interact with participant age and resulted in generally longer latencies and larger latency differences between upright and inverted faces in the child participants.

N170 Component

Amplitude

The central face component, the N170, showed an expected main effect of orientation, F(1,22) = 13.14, p =.001, η 2 = .37, however this was qualified by an interaction between orientation and participant age, F(1,22) = 27.99, p <.001, η 2 = .56. Pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences in processing for upright faces between children(M = .51 μV, SD = 3.42), and adults (M = -4.26 μV, SD = 2.22), F(1,22) = 16.94, p <.001, η 2 = .44, as well as in regard to inverted faces between children(M = 3.65 μV, SD = 3.97), and adults (M = -4.85 μV, SD = 2.24), F(1,22) = 43.51, p <.001, η 2 = .66.While children’s amplitudes significantly differed between upright and inverted faces, F(1,10) = 26.40, p <.001, η 2 = .72, adults’ amplitudes did not, F(1,12) = 2.24, p =.16, η 2 = .16.

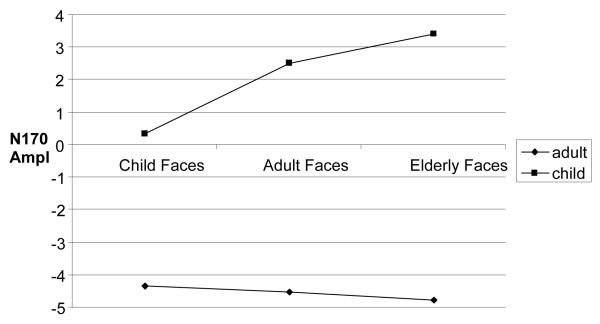

There was also a main effect of face age, F(1,22) = 8.29, p =.001, η 2 = .27, which was qualified by an interaction between face age and participant age F(2,44) = 14.03, p <.001, η 2= .39, indicating an own-age bias for child participants. Posthoc comparisons showed that child participants’ N170 amplitudes were significantly larger in response to child faces (M = .32 μV, SD = 4.01) than in response to adult faces (M = 2.50 μV, SD = 3.82) and elderly faces (M = 3.42 μV, SD = 3.54), F(2,20) = 10.55, p <.01, η 2 = .51 . However, there was no difference between adult faces and elderly faces, p = .65. Adult participants did not evince any differences between the children’s faces (M = -4.34 μV, SD = 2.22), adult faces (M = -4.53 μV, SD = 2.14), or elderly faces (M = -4.78 μV, SD = 2.12 F(2,24) = 1.19, p <.18, η 2 = .14. These analyses, depicted in fig. 4, uncover an own-age bias in children’s processing of facial information..

Figure 4.

Plot shows the interaction between picture of face and age of participants in the N170 component, expressed in Amplitude.

Latency

Analyses revealed a main effect of orientation, F(1,22) = 11.87, p =.002, η 2 =.35, qualified by an interaction between orientation and participant age, F(1,22) = 9.53, p =.005, η 2 = .30. Pairwise comparisons revealed that adults showed faster N170 latencies to upright faces (M = 115.67 ms, SD = 10.29) than to inverted faces (M = 124.49 ms, SD = 9.50), F(1,12) = 37.30, p <.001, η 2 = .76, whereas upright (M = 201.61 ms, SD = 23.34) and inverted faces (M = 202.10 ms, SD = 22.66) did not differ in regard to N170 latencies in the child participants, F(1,10) = 1.29, p =.84, η 2 = .004.

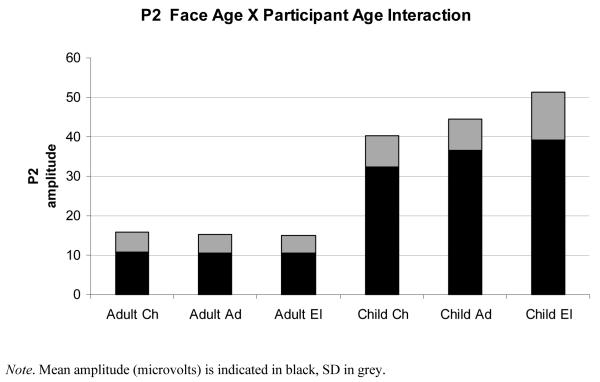

P2 Component

We predicted smaller P2 amplitudes for own-age and upright faces compared to other-age and inverted faces. With experience, however, the P2 would diminish over occipitemporal regions (Stahl et al., 2008). Thus, we might expect an ‘expert’ like response from adults, but not from children due to the fact that children never have been members of an adult group. No such effect from inverted faces was expected.

Amplitude

There was a main effect of orientation, F(1,22) = 24.30, p <.001, η2 = .53, however orientation significantly interacted with participant age, F(1,22) = 17.96, p <.001, η 2 = .45. Pairwise comparisons showed that child participants evinced smaller P2 amplitudes for upright faces (M = 16.20 μV, SD = 5.18) than for inverted faces (M = 19.81 μV, SD = 3.41), F(1,10) = 19.71, p =.001, η 2 = .66. Adults however, did not show such difference between upright faces (M = 5.17 μV, SD = 2.35) and inverted faces (M = 5.45 μV, SD = 2.32), F(1,12) = 1.35, p =.27, η 2 = .10. There was also a main effect of face age, F(2,44) = 4.51, p =.02, η 2 = .17, but this effect was qualified by a face age × participant age interaction, F(2,44) = 5.47, p <.01, η 2 = .20. Follow-up tests showed that P2 amplitudes recorded in child participants were slightly smaller in response to children’s faces (M = 32.32 μV, SD = 7.93) than for elderly faces (M = 39.24 μV, SD = 12.11), F(1,20) = 4.32, p =.03, η 2 = .30, although not significantly smaller than for adult faces (M = 36.49 μV, SD = 7.85), p = .25. In addition, child participants’ P2 amplitudes did not differ between adult faces and elderly adult faces, p = .90. Adult participants’ P2 amplitudes were not different for children’s faces (M = 10.86 μV, SD = 4.95) compared to adult faces (M = 10.44 μV, SD = 4.71), or elderly faces (M = 10.56 μV, SD = 4.31) (see fig. 5), F(1,24) = .87, p <.50, η 2= .05.

Figure 5.

Figure shows the interaction between picture of face and age of participants in the Amplitude P2 component.

Latency

There was a main effect of orientation for the P2 component, F(1,23) = 7,76, p =.01, η 2= .25, whereby faces presented upright (M = 263.77 ms, SD = 67.82) resulted in significantly shorter latencies than faces presented inverted (M = 269.49 ms, SD = 68.22).

In sum, P2 amplitude results showed only weak support for an own-age bias as illustrated by the face age × participant age interaction for child participants in relation to elderly adults of whom children have less experience. However, there was evidence for an ‘expert’ like response from adults, resulting in the abolishment of the inversion effect. P2 latencies were shorter for upright faces than for inverted faces.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was twofold: first we investigated the different neural processing underlying own-age versus other-age faces. Secondly, the effect of facial orientation in 5-year-old children and adults was examined. We found significant ERP effects of both facial type and orientation, and significant ERP interaction effects between each of these two factors and age. In the majority of our analyses, the effect size is regarded strong, which contribute to a high reliability of our results.

Neural processing underlying own-age versus other-age faces

This study is the first to our knowledge that has studied the neural processing of own-age versus other-age faces in children and adults. In regard to P1 effects, we found that orientation did not interact with participant age when amplitude measures were analyzed, but orientation did interact with participant age and resulted in generally slower processing and larger latency differences between upright and inverted faces in the child participants. Thus, we were able to show the P1’s amplitude sensitivity to low-level properties in both child and adult participants. Interestingly, we found a main effect of face age so that faces of children elicited the smallest amplitudes and significantly differed from elderly faces, but not from adult faces at the same time as faces of adult and elderly did not differ. A relevant question is whether this result could be due to low-level differences (e.g., spatial frequency differences) in the faces of different ages? Because we did not estimate the spatial frequency of the stimuli material it is hard to conclude. However, elderly faces tend to have more wrinkles and perhaps less smooth skin than 5- year-old children — differences that could impact the P1 sensitivity to lower level frequency. If so, it would support the ecological validity of our stimuli material.

With regard to the P2 component, we showed that child participants’ P2 amplitudes were slightly smaller for pictures of children than for pictures of elderly adults, although not significantly smaller than for adults. In addition, child participants’ P2 amplitudes did not differ between adults and elderly adults. Adult participants’ P2 were not different for pictures of children than of pictures of adults, or of elderly adults, and confirmed the expectation resulting from the work of Stahl et al. (2008); the assumption that expertise modulates own-age bias and results in abolishing the effect. In fact, a recent report shows that the P2 component of the own-age bias in young participants were similar to those of an own-race bias investigated in the Stahl et al. (2008) study, suggesting that similar mechanisms underlie these face memory biases (Wiese, Schweinberger, & Hansen, 2008). Unfortunately we are unable to offer an explanation as to why the ‘expert’ response occurs in relation to elderly faces, but all of the adult participants had quite extensive current experience with elderly.

In sum, P2 amplitude results showed weak support for an own-age bias by the picture × age interaction for child participants, however there was evidence for an ‘expert’ like response from adults, replicating recent reports about P2 as an expert-sensitive component to other-race faces to account for similar effects in regard to other-age faces. It is not possible to rule out whether this effect was mainly due to qualitative differences, i.e. adults’ earlier membership in a child group (cf. IOM; Sporer, 2001), or whether this effect is due to quantitative differences, i.e. more experience with children.

For the N170 component, we found an interaction between face age and age of participants, indicating an own-age bias for child participants. Child participants’ N170 amplitudes were larger for pictures of children than pictures of adults and of elderly adults, albeit there were no differences in child participants’ N170 in regard to pictures of adults versus elderly adults. These analyses uncover an own-age bias in children’s processing of facial information for the most face selective component. Interestingly, in line with the results of Anastasi and Rhodes’ (2005) study that found an inverted own-age bias for children, our results confirm their result as children in fact showed larger amplitudes for child faces than for other age faces. In relation to the theoretical prediction available (Meissner & Brigham, 2001; Sporer, 2001), this is thus the second study that finds evidence for an opposite pattern with children than what has typically been observed with adults (cf. Anastasi & Rhodes, 2005).

In all, these results suggest that the age of the face is important in regard to the experience the subject has with the target. The degrees to which subjects have been members of a specific group also affected our results, especially highlighted in the P2 adult performance. In the current study it is, however, not possible to tease apart the contribution of the adults’ current experience as parents to 5-year old children, and their past experience as being part of a child group.

Our results support a general face mechanism that is specifically biased against processing any face. Beyond this general device, with specific experience and motivational aspects however, specialized cognitive strategies -- such as configural processing that reinforces encoding of in-group members and categorical processing that prevents encoding out-group members’ faces as individuals (Bernstein, Young, & Hugenberg, 2007; Sporer, 2001) — develops. These cognitive strategies may well reinforce neural activity, and vice versa, forming a loop between social influence and neural correlates that is modulated by human cognition.

With regard to the present study, we picked 5-year-old children, because they attend preschool or kindergarten on a daily basis and need to quickly adapt to new social and cognitive demands from their preschool fellows. Dual-representational capabilities such as imaginary play, working with letters, and elaborated theory of mind skills are highly warranted in this phase of development in relation to own-age individuals (Melinder, Endestad, & Magnussen, 2006). The rational for why own-age mates would elicit central motivational factors resulting in superior encoding and recognition in 5-year-old children, is the assumption that reciprocity in play, activities, and general identification triggers social categorization. Mere social categorization has been found sufficient to elicit an own-group bias in face recognition of own versus other race (Bernstein, Young, & Hugenberg, 2007), and we found evidence for parallel effects in regard to the age of the face. This conclusion is supported by the fact that children still have an extended daily experience with adults, quantitatively actually exceeding experience with own-age peers.

Effects of Orientation

Orientation of faces had a differential effect on performances. For the P1 component, inverted faces elicited larger amplitudes than upright faces, independent of participant age. In regard to latencies, orientation did interact with participant age and resulted in generally longer latencies and larger latency differences between upright and inverted faces in the child participants compared to adult participants.

The P2 however, showed a mixed result for the interaction between orientation and age of participants. Specifically, child participants evinced smaller P2 amplitudes for upright faces than for inverted faces, whereas adults did not. By contrast, we found no differences between children and adults in regard to latencies for upright versus inverted faces. The interpretation of the child P2 amplitude findings should be carefully done because as we found a significant difference between right and left hemispheric activation. However, our interest in the P2 component was primarily driven by our prediction regarding adult participants and not children. We therefore conclude that the important finding is unaffected by the children’s hemispheric differences.

For the N170 component, child participants evinced similar latencies to inverted and upright faces, whereas adults evinced significantly shorter N170 latencies to upright faces than to inverted faces. A review of the literature suggests that it is common to find larger amplitudes for inverted faces in adults, but not in children. Actually, Itier and Taylor (2004c) found smaller amplitudes for inverted faces than for upright faces in 8-9-year old children despite the fact that in the same sample effects of orientation on accuracy and reaction times measures were observed. In terms of amplitudes, we found no differences between adults’ processing of upright and inverted faces, but we did so in regard to children’s processing.

Others have found inversion effects from an early age (Itier & Taylor, 2004c), and this has also been observed in infants as young as six months (deHaan, Pascalis & Johnson, 2002).These findings suggests an onset as early as 100 ms in ERPs over right occipital-temporal areas that are sensitive to the composition of faces. In regard to latency, adults showed an orientation effect in the N170 whereas children did not (we found an effect of orientation for children when amplitudes was measured). For the P1, we found evidence for an effect of orientation in both children and adults. Finally for P2, inverted faces were processes more slowly than upright faces. Processes underlying the inversion effect are multidimensional; on the one hand they are strongly related to development, which is in agreement with the idea of a tuning of perceptual areas towards the upright human face. On the other hand, recent fMRI evidence demonstrate that face wholes and parts elicit similar activation within face selective areas in adults (Harris & Aguirre, 2008), which argue against the idea that face parts are processed by a general object recognition system; the holistic view (Tanaka & Farah, 1993). Harris and Aguirre propose instead a unified system that is responsible for processing of faces in a holistic manner and also contains representations of individual face parts. This system was modulated by familiarity that influenced the magnitude to which holistic and part-based processing was engaged, suggesting an intimate interplay between experiences (i.e. familiarity) and neural mechanisms.

Caveats and future studies

Our original experimental design included a recognition phase that would have allowed us to understand more about memory for faces. However, after piloting we decided to omit a recognition phase as it proved too taxing for children, specifically the length of the experiment became to exhausting for the children. In the future, it would be important to reduce the length of the study phase, for example by taking out the faces of elderly people, and add a later test phase in which recognition capabilities were measured. Much in the same vein, we piloted with an elderly population to look for potential effects of their face processing. Because the data indicated impairments in sensory and cognitive capabilities, comparing elderly adults’ performance to child and adult participants’ would not give an accurate picture of age trends as the elderly group was impaired and the other two were not. A way around this issue might be to test participants for standardized criterion, i.e., employ different cut scores for floor and ceiling effects.

Another criticism of our study is that we did not control for the different aspects that the experiential hypothesis posed. For example, we did not exact estimate participants’ experience with own and other age group, and we did not measure a specific social categorization variable, except from age. Future studies should look into these issues and more explicitly measure relevant aspects of experience and social categorization. In the same line and adding to our understanding of the different possibilities launched by the experiential versus the IOM hypotheses, testing other age groups representing distinct developmental stages with clear in-group motivational drives would be informative. One such group would clearly be teenagers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have used established paradigms in a passive viewing approach to examine developmental changes of own-age and inversion effects within face-selective regions of the right ventral occipital-temporal cortex. In an advance over previous work, we have fully integrated an eye tracking camera into the EEG system. Second, we included strict age group and did not prime participants during the encoding phase to think about or evaluate the different ages of the stimuli as in the Anastasi and Rhodes’ (2005, 2006) studies. Third, by highlighting the basic encoding processes of own versus other-age faces, we contribute to the understanding how experience influences human’s attentiveness. The finding of an own-age effect in 5-year-old children provides an important constraint for models of how in- out models of face processing occur and develop within the brain as well as in relation to the social world.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grants from the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (06/34707) to the first and second authors. Charles Nelson was supported by NIH grant MH078829. We thank EKUPs assistants T. Berge, M. Huth and T. Moe.

Footnotes

Piloting with an elderly population (corresponding to the age of the faces in the photos) showed that their encoding and memory capabilities (face recognition) were significantly worse than 5-year-olds, and adults. As a rule, the data was highly variable, and indicated impairments (e.g., sensory, cognitive) that influenced their performance. To compare elderly adults to child and adult participants would therefore not give an accurate picture of age trends as the elderly group was impaired and the other two were not.

References

- Anastasi JS, Rhodes MG. An own-age bias in face recognition for children and older adults. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005;12(6):1043–1047. doi: 10.3758/bf03206441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi JS, Rhodes MG. Evidence for an own-age bias in face recognition. North American Journal of Psychology. 2006;8:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bentin S, Allison T, Puce A, Perez E, McCarthy G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1996;8:551–565. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.6.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein MJ, Young SG, Hugenberg K. The crosscategory effect: mere social categorization is sufficient to elicit an own-group bias in face recognition. Psychological Science. 2007;18(8):706–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance JE, Goldstein AG. Face recognition memory: implications for children’s eye-witness testimony. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chung MS, Thomson DM. Development of face recognition. The British Journal of Psychology. 1995;86:55–87. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1995.tb02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MS. Face recognition: effects of age of subjects and age of stimulus faces. Korean Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1997;10:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan M. Neurocognitive mechanisms for the development of face processing. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2nd edition MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2008. pp. 509–520. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan M, Nelson CA. Developmental Psychology. Vol. 35. 1999. Brain activity differentiates face and object processing in 6-month-old infants; pp. 1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan M, Pascalis O, Johnson MH. Specialization of neural mechanisms underlying face recognition in human infants. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:1–11. doi: 10.1162/089892902317236849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ, Tanaka JW, Drain HM. What causes the face inversion effect? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1995;21:628–634. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.21.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ, Wilson KD, Drain M, Tanaka JN. What is “special” about face perception? Psychological Review. 1998;105(3):482–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George N, Evans J, Fiori N, Davidoff J, Renault B. Brain events related to normal and moderately scrambled faces. Cognitive Brain Research. 1996;4:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(95)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönqvist H, Gredebäck G, von Hofsten C. Developmental Asymmetries between Horizontal and Vertical Tracking. Vision Research. 2006;46(11):1754–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Aguire GK. The representation of parts and wholes in face-selective cortex. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(5):863–878. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4(6):233. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier RJ, Taylor MJ. Effects of repetition and configural changes on the development of face recognition processes. Developmental Science. 2004c;7(4):469–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier RJ, Taylor MJ. Face inversion and contrast-reversal effects across development: in contrast to the expertise theory. Developmental Science. 2004b;7(2):246–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier RJ, Taylor MJ. Face recognition memory and configural processing: a developmental ERP study using upright, inverted, and contrast reversed faces. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2004a;16(3):487–502. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(11):4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuefner D, Cassia VM, Picozzi M, Bricolo E. Do all kids look alike? Evidence for an other-age effect in adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;34(4):811–817. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.34.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner CA, Brigham JC. Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: a meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, & Law. 2001;7(7):3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Melinder A, Endestad T, Magnusse S. Relations between Episodic Memory, Theory of Mind, Cognitive Inhibition, and Suggestibility in the Preschool Child. Journal of Scandinavian Psychology. 2006;47:485–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA. The development and neural bases of face recognition. Infant and Child Development. 2001;10:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pascalis O, Scott LS, Kelly DJ, Shannon RW, Nicholson E, Coleman M, et al. Plasticity of face processing in infancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(14):5297–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406627102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect TJ, Moon H. The own-age effect in face recognition. In: Duncan J, Phillips L, McLeod P, editors. Measuring the mind: Speed, control, and age. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P, Yahr J, Kuhn A, Slater AM, Pascalils O. Representation of the gender of human faces by infants: a preference for female. Perception. 2002;31(9):1109–1121. doi: 10.1068/p3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, De Schonen S. Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three-month-old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(7):1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, Pallier C, Argenti AM, Ventureyra VA, de Schonen S. Reversibility of the other-race effect in face recognition during childhood. Psychological Science. 2005;16(6):440–4. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporer SL. Recognizing faces of other ethnic groups: an integration of theories. Psychology, Public Policy, & Law. 2001;7:36–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl J, Wiese H, Schweinberger SR. Expertise and own-race bias in face processing: an event-related potential study. NeuroReport. 2008;19(5):583–587. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f97b4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, Farah MJ. Parts and wholes in face recognition. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1993;2:225–245. doi: 10.1080/14640749308401045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, Kiefer M, Bukach CM. A holistic account of the own-race effect in face recognition: evidence from a cross-cultural study. Cognition. 2004;98(1):B1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, Batty M, Itier RJ. The faces of development: a review of early face processing over childhood. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2004;16(8):1426–42. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Nelson CA. Perceptual priming for upright and inverted faces in infants and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2001;79:1–22. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese H, Schweinberger SR, Hansen K. The Age of the Beholder: ERP Evidence of an Own-Age Bias in Face Memory. Neuropsychologia. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.007. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DB, Stroud JN. Age differences in lineup identification accuracy: people are better with their own age. Law and human behavior. 2002;26(6):641–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1020981501383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Looking at upside-down faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1969;81:141–145. [Google Scholar]