Abstract

Community and high-risk sample studies suggest that alcohol dependence is relatively stable and chronic. By contrast, epidemiological studies demonstrate a strong age-graded decline whereby alcohol dependence tends to peak in early adulthood and declines thereafter. The authors identified the latent trajectory structure of past-year alcohol dependence to investigate (a) whether the syndrome is characterized by symptom profiles and (b) the extent to which the syndrome is stable and persistent. Data from current drinkers (N = 4,003) in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth were analyzed across two waves: 1989 (ages 24–32 years) and 1994 (ages 29–37 years). Three classes of alcohol dependence were observed; symptom endorsement probabilities increased across successively severe classes. Latent transition analyses showed high rates of stability, supporting alcohol dependence as a relatively chronic condition. Although there was evidence of progression to more severe dependence, there was greater syndrome remission. Trajectory classes and transition probabilities were generalizable across race and sex and, to a lesser extent, age cohort and family history of alcoholism.

Keywords: alcohol dependence, transition, stability, developmental

Psychometric research into the “nature” of alcohol use disorders seeks to evaluate nosologies of problematic alcohol involvement (see, e.g., Bucholz, Heath, Reich, Hesselbrock, Kramer, Nurnberger, & Schuckit., 1996; B. O. Muthen, Grant & Hasin, 1993) by describing the latent variables that underlie diagnostic data. Consideration of subtypes is informative because subtypes allow researchers to identify (and test theories regarding) specific subgroups of individuals with alcohol-related symptomatology (e.g., Babor, Hofmann, Del Boca, Hesselbrock, Meyer, Dolinsky, & Rounsaville, 1992; Bucholz et al., 1996). Alternately, approaches to characterizing trajectories (or course) of alcohol involvement have been developed, allowing researchers to characterize distinct temporal patterns of alcohol involvement over the course of time (e.g., Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002; Colder, Campbell, Ruel, Richardson, & Flay, 2002; Li, Duncan, & Hops, 2001; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996a; Tucker, Orlando, & Ellickson, 2003). Although both subtyping and trajectory studies have provided valuable perspectives on problematic alcohol involvement, each has noteworthy limitations. Typological research uses a rich level of fine-grained detail but often is limited by reliance on cross-sectional assessment. The trajectory/course literature has suffered from the inverse limitation—relying on prospective assessments of a predominantly univariate universe (e.g., repeated assessments of binge drinking). A more comprehensive approach would ideally include assessment of alcohol indicators (e.g., individual dependence symptoms) within a longitudinal framework. The integration of these two approaches is the goal of the present study.

Previous Subtyping Research

In the literature on subtyping, subgroups of individuals with alcohol involvement are identified on the basis of relations among manifest indicators of alcohol use and alcohol-related symptoms as well as related correlates (e.g., personality variables, comorbid psychopathology, family history of alcoholism). Although sometimes including information about course (e.g., age of onset or desistance in models proposed by Zucker [1986] or Babor et al. [1992]), the identification of latent subtypes has tended to focus on cross-sectional differences (e.g., Babor et al., 1992). Recent work has attempted to identify subgroups on the basis of alcohol symptom profiles endorsed by individuals in heterogeneous populations (Bucholz et al., 1996; Heath et al., 1994). The extant research using this approach suggests that classes differ in degree rather than kind (Bucholz et al., 1996; Heath et al., 1994). In a sample (n = 2,551) of relatives of individuals, Bucholz et al. (1996) found evidence for four distinct classes characterized by lifetime alcohol-related symptoms: an asymptomatic, nonproblem-drinking class followed by mild, moderate, and severe classes of alcohol dependent individuals; the likelihood of endorsing given symptom increased in successively severe classes across most indicators. Withdrawal symptoms proved to be the only exception to the monotonic increase in symptom endorsement in that endorsement of withdrawal characterized members in the most severe class only Similar findings resulted from latent class analyses of general population samples (Heath et al., 1994; Nelson, Heath, & Kessler, 1998).

Most subtyping studies have relied on cross-sectional assessments using retrospective, lifetime report. If adequate assessment of the time domain is crucial to our understanding of variability in problematic alcohol involvement, we must undertake such assessment with the broad view and increased precision that prospective methodologies alone can provide. This view is consistent with Zucker’s developmental typology of alcoholism (Zucker, 1986, 1994), which emphasizes not only the presence of an alcohol use disorder but its behavior over time by placing the timing of the disorder in a developmental context.

Furthermore, previous symptom–profile research may be limited by its reliance on lifetime assessment of alcohol-related problems (e.g., Bucholz et al., 1996). Although useful for ascertaining the largest proportion of affected relatives in proband’s family pedigree when the effects of familial–genetic risk are under investigation, meaningful information may be lost when only the occurrence and not the timing of particular symptoms is considered. Additionally, lifetime diagnosis is notoriously unreliable (e.g., see Culverhouse et al., 2005; Van diver & Sher, 1991) and this imprecision can further compromise nosologic research. Although the use of lifetime symptom endorsement may yield latent variables similar to those based on past-year endorsement (O’Neill, Sher, Jackson, & Wood, 2003), variables derived in this way are unsuitable for longitudinal analysis because it is not possible to distinguish remission from persistence and “negative prevalence” (i.e., failure to endorse previously endorsed lifetime symptoms) presents interpretive challenges.

Previous Trajectory Research

In direct contrast to the literature on subtyping, trajectories most often are identified on the basis of repeated assessments of alcohol-related behaviors. Third variables may be related to identified trajectories but typically are not used to identify the trajectories themselves. The identification of trajectories is central to resolving questions about variation in course (e.g., age of onset, persistence, and desistance), for example, those for whom alcohol problems will remit and those for whom alcohol problems represent a lifecourse persistent phenomenon. Zucker’s developmental perspective has influenced research that systematically considers the time domain in alcoholism subtypes within prospective studies (Gotham, Sher, & Wood, 2003; Schulenberg et al. 1996a; Schulenberg, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1996b). In Zucker’s view, subtypes of alcoholism are distinguished to a large extent by patterns of alcohol involvement over time. In one of the first applications of this theory, meaningful trajectories of frequent binge drinking in young adults were identified using cluster analysis (Schulenberg et al., 1996a). Six patterns of heavy alcohol involvement that differ in meaningful ways emerged: chronic (binge drinking over time), decreased, increased, fling, rare, and never. For instance, individuals in the chronic and decreased groups reported similar rates of problems and “unhealthy” attitudes at baseline but, over time, individuals exhibiting a decrease in binge drinking frequency were at lower risk for alcohol problems and other problem behaviors (Schulenberg et al., 1996b). These respective patterns are consistent, at least at a conceptual level, with the developmentally cumulative and developmentally limited alcoholism “subtypes” described by Zucker (1986, Zucker, R. A. 1994). Subsequently, other research groups have described latent trajectories and related them to etiologically relevant background variables (e.g., family history of alcoholism; delinquency; negative affect; Chassin et al., 2002; Colder et al., 2002; Jackson & Sher, 2005; Schulenberg et al., 1996b) or time-varying covariates (e.g., peer variables, family structure, deviance; Li et al., 2001; Tucker et al., 2003) and/or related use trajectories to later alcohol and other drug problems (Chassin et al., 2002; Colder et al., 2002; Li et al., 2001; B. O. Muthen & Muthen, 2000; Tucker et al., 2003). Although each of these studies has used prospective data, each has been limited to examination of adolescence and emerging adulthood. There is a deficiency in knowledge, however, in terms of alcohol dependence course in adults, and the current study aims to address this gap.

Extant research suggests that course of alcohol dependence may differ across numerous subgroups both in kind (i.e., the manifestation of alcohol dependence) and in degree (i.e., the course of alcohol dependence). Gender, age, and racial differences have been observed in rates of alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use disorders (Grant, 1997; Grant et al., 2004a, 2004b; Hasin & Grant, 2004; Kessler et al., 1994), but the extent to which the prospective characterization of alcohol dependence differs across these subgroups has scarcely been examined. In addition, positive family history of alcoholism is associated with increased risk for alcohol use disorders (Sher, 1991; Windle & Searles, 1990), and we observed in a prospective college-student sample that individuals with a family history of alcoholism were less likely to remit out of high-risk drinking (Jackson, Sher, Gotham, & Wood, 2001). However, prospective course of alcohol dependence has not yet been examined as a function of family history.

Integrating Typological and Trajectory Approaches Using Latent Transition Analysis

The previous work of our colleagues (Gotham et al., 2003; Jackson, Sher, & Wood, 2000), the Monitoring the Future group (Schulenberg et al., 1996a; 1996b), and others (Chassin et al., 2002; Tucker et al., 2003) considers trajectories of problematic alcohol involvement from a developmental perspective. However, systematic analysis of symptom configuration and stability (vs. progression or remission) has been lacking in this research. The present study sought to integrate the symptom profile (i.e., subtype) and trajectory approaches by using prospective assessments of alcohol dependence symptoms from two time points. This integration allows for a more methodologically advanced inquiry into questions that have long been of interest to researchers in the alcohol dependence area. The motivation for the current study was to examine the chronicity of alcohol dependence. Community and high-risk sample studies show that alcohol dependence tends to be relatively stable and chronic, with sizable retention of the alcohol dependence diagnoses over short-term (1-year; Hasin, Van Rossem, McCloud, & Endicott, 1997) and moderate-term (4- and 5-year; Hasin, Grant, & Endicott, 1990; Schuckit, Smith, & Landi, 2000) intervals. Yet, juxtaposed with these findings are cross-sectional epidemiological studies (e.g., Grant & Harford, 1994; Hasin & Grant, 2004) that consistently demonstrate a strong age-graded decline whereby alcohol dependence tends to peak in early adulthood (in the 20s; particularly the early 20s; Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004), suggesting that individuals developmentally mature out of alcohol dependence. Certainly there are potential confounds such as cohort effects, biased recall, and differential mortality, but these potential limitations of cross-sectional, epidemiological surveys are unlikely to explain this seeming discrepancy (e.g., if differential mortality in cross-sectional explanations were likely to the explain the large decreases in prevalence, age differences in the prevalence of alcohol dependence would be expected to be more evident in older adulthood or middle adulthood, but they are most pronounced in younger adulthood).

The goal of the current study was to examine the extent to which alcohol dependence is chronic. Specifically, we investigated patterns of individual symptom clustering (i.e., syndrome manifestation) and determined whether syndrome persistence, desistence, or progression characterizes latent person-level groups via the use of latent transition analysis. The current study undertook prospective person-level analyses to identify symptom profiles while representing persistence or desistence simultaneously. By integrating subtype and trajectory approaches, the current study sought to (a) examine the degree to which the physiological versus nonphysiological dependence distinction is useful in subtyping alcohol dependence using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM–IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) specifications and (b) investigate whether alcohol dependence is characteristically chronic and persistent in nature. We focused on alcohol dependence symptom-profiles to identify subgroups in the current study because they are consistent with the DSM–IV’s symptom focus and because they represent the current state of the art in typological research toward DSM–V. Although we could have included alternate indicators (e.g., family history of alcoholism, personality) to determine subtypes, we feel there may be heuristic advantages to distinguishing potential predictors from outcomes. In pursuing the goals of the current study, we also sought to explore whether the latent trajectory structure of past-year alcohol dependence was generalizable across subgroups known to vary in their substance use at certain points in development: men and women, Hispanics, Blacks and Whites, younger and older adults, and those with and without family history of alcoholism.

Method

Sample

The sample was drawn from a study sponsored by United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY; Center for Human Resource Research, 1993). The primary focus of the NLSY was on the labor market experiences of a large group of young men and women, diverse with regard to race, gender, and socioeconomic status. The NLSY was administered to 12,686 noninstitutionalized civilian young adults (ages 14–22 years) beginning in 1979 and annually or biannually thereafter. Using a cohort sequential design, NLSY gathered a generalizable, multistage national probability sample that oversampled women, ethnic minority groups, and military youth. The sample was stratified by dwelling units and group quarter units.

Assessments of alcohol use and alcohol use disorder were added as supplements to the study at some waves of data collection. In 1989 and 1994 (the 10th and 14th years of the study, respectively), items that represented current conceptualizations of alcohol dependence were included. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded these supplemented assessments of alcohol and drug use and problems in the NLSY.

The total sample surveyed in the initial 1979 NLSY assessment included 12,686 individuals. A total of 10,605 (83.6%) were interviewed in 1989, and 8,889 (70.1%) were interviewed in 1994; 67.5% (n = 8,560 of 12,686) of the full sample was interviewed at both 1989 and 1994. However, we were interested only in those individuals who endorsed ever consuming alcohol (94.6%, or n = 8,095 of the 8,560). We used listwise deletion. In the NLSY survey, only current (past-month) drinkers were eligible to complete the alcohol dependence items, which greatly reduced our sample size. Rates of item responding ranged from 5,013 (a withdrawal item at Time 2) to 6,628 (a reduced activities item at Time 1), although all alcohol symptom items at Times 1 and 2 were answered by only 4,003 participants, our final sample size. The final sample, hence, comprised current drinkers and was representative of both men and women (60% male, 40% female) and was racially diverse (18% Hispanic, 25% Black, 56% Non-Black, Non-Hispanic). The participants ranged in age from 24 to 32 years at Time 1 and ages 29 to 37 years at Time 2 (1994).

Attrition Analysis

We conducted attrition analyses to determine differences between those who were successfully interviewed at Time 2 and those who were not reinterviewed. Only those who endorsed lifetime drinking and responded to all alcohol symptom items were included in attrition analyses. Significant differences existed in gender, frequency of drinking, and heavy drinking at Time 1 and number of symptom domains endorsed at Time 1. White subjects were less likely to be interviewed,χ2(2, N = 6,528) = 395.578, p < .001, as were older participants, F(1, 6,527) = 61.28, p < .001 (M = 28.45 vs. M = 27.88) and heavier quantity drinkers, F(1, 6,519) = 4.04 p < .05 (M = 3.42 vs. M = 3.11 drinks on an average drinking day).

Measures

Trained interviewers assessed a number of domains in addition to alcohol and drug use (i.e., employment history, criminal record, educational attainment, etc.). Participants were asked a number of questions regarding their alcohol consumption and experiences related to drinking.

Demographics

Sex and racial group were assessed in the NLSY 1979 assessment. Participants were classified into three groups: Black, Hispanic, Non-Black/Non-Hispanic. Age was assessed as of the interview date in 1989. Because our sample was not circumscribed to a single developmental stage (the youngest participants were just moving in to the labor market whereas the oldest participants were approaching the age of 40), we created three age cohorts and investigated whether the latent trajectory structure of alcohol dependence was generalized across the three age groups. A three-level age cohort variable was created as follows: young (< 27 years old at Time 1), middle (27–29 years old), and older (>29 years old).

Alcohol dependence symptoms

We identified 16 past-year alcohol use disorder items in the NLSY that corresponded to DSM–IV alcohol dependence.1 Table 1 presents the items used to represent each of the seven broad DSM–IV alcohol symptoms in the study. The response scale was 1 = never happened, 2 = happened in lifetime other than past year, 3 = happened one time in past year, 4 = happened two times in past year, and 5 = happened three or more times in past year. Items were scored 0 and 1, where 1 indicated the presence of the symptom within the past year. When multiple alcohol dependence symptom items for a given DSM symptom were present, the DSM symptom was coded as positive if any one of the symptom items was endorsed. Items were developed for the NLSY survey as well as for the National Health Interview Survey based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–III–R; 3rd ed., revised; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria that prevailed at the time (Veazie & Smith, 2000). As noted previously, only respondents who reported having consumed a drink in the past month were eligible to complete the alcohol dependence items. Table 2 presents past-year and lifetime prevalence rates that correspond to each of the seven alcohol dependence symptoms specified in the DSM–IV as well as the rate of alcohol dependence in the sample at each time point. Because Black and Hispanic respondents were oversampled in the NLSY, the rates presented in Table 2 are presented separately by racial group.

Table 1.

Alcohol Dependence Items Used in the Study

| DSM-IV symptoms | Individual items | |

|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | T1 | Found that the same amount had less effect |

| T2 | Needed to drink more to get same effect | |

| Withdrawal | W1 | Found yourself sweating heavily or shaking after drinking or the morning after |

| W2 | Heard or seen things that weren’t really there after drinking, or the morning after | |

| W3 | Taken a drink to keep yourself from shaking or feeling sick either after drinking, or the morning after | |

| Using more or for longer than intended | C1 | Ended up drinking much more than you intended to |

| C2 | Found it difficult to stop drinking once you started | |

| C3 | Kept on drinking for a longer period of time than you intended | |

| Desire to quit/failed attempts to cut down or quit | FA | Wanted to or actually tried to cut down or stop drinking but found you couldn’t do it |

| Reduced activities | A1 | Given up or cut down on activities or interests like sports or associations with friends, in order to drink |

| A2 | Stayed away from work or gone to work late because of drinking or a hangover | |

| A3 | Lost ties with or drifted apart from a family member or friend because of drinking | |

| Continued use despite consequences | U1 | Continued to drink even though it was a threat to your health |

| U2 | Kept drinking even thought it caused you emotional problems | |

| Great deal of time spent drinking or getting over effects | TM1 | Spent a lot of time drinking or getting over its effects |

| TM2 | Hangover interfered with things supposed to do |

Table 2.

Past-Year Prevalence Rates at Time 1 (1989) and Time (1994)

| 1989 (%) | 1994 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | ||

| Hispanic | 16.5 | 17.6 |

| Black | 18.5 | 22.0 |

| White | 13.9 | 11.4 |

| Full sample | 15.5 | 15.2 |

| Withdrawal | ||

| Hispanic | 8.7 | 10.7 |

| Black | 7.5 | 9.9 |

| White | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Full Sample | 7.6 | 8.4 |

| Using more or for longer than intended | ||

| Hispanic | 19.1 | 19.0 |

| Black | 16.1 | 20.1 |

| White | 21.3 | 19.8 |

| Full Sample | 19.6 | 19.7 |

| Desire to quit/failed attempts to quit | ||

| Hispanic | 4.8 | 5.9 |

| Black | 5.8 | 8.0 |

| White | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| Full Sample | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| Reduced activities | ||

| Hispanic | 10.1 | 9.3 |

| Black | 8.8 | 9.4 |

| White | 7.9 | 7.2 |

| Full Sample | 8.5 | 8.2 |

| Continued use despite consequences | ||

| Hispanic | 8.5 | 7.8 |

| Black | 6.8 | 9.3 |

| White | 4.9 | 5.7 |

| Full Sample | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| Great deal of time spent drinking or getting over effects | ||

| Hispanic | 6.2 | 9.3 |

| Black | 7.5 | 9.4 |

| White | 7.9 | 7.7 |

| Full Sample | 7.4 | 8.4 |

| Alcohol dependence (three or more of above) | ||

| Hispanic | 10.4 | 11.3 |

| Black | 10.1 | 12.9 |

| White | 9.2 | 8.2 |

| Full sample | 9.6 | 9.9 |

Note. N = 4,003. Hispanic n = 732; Black n = 1,010; White n = 2,261.

Family history of alcoholism

The family history variable was taken from a set of items assessed in 1988. First, an item asked whether the respondent had any relatives who were “alcoholic” (50% of the sample endorsed this item). Then, respondents who endorsed this item were further probed and asked to provide the nature of their relationship with the alcoholic relative. Options included biological father/mother, step, adoptive, or foster father/mother, biological brother/sister, step, half, or adoptive brother/sister, grandfather/grandmother on father/mother side, blood uncle/aunt/cousin on father/mother side, other blood relative, current husband/wife, and ex-husband/wife. Respondents were given options for up to six relatives. Biological parents and siblings were coded as positive history of alcoholism in a first-degree relative; grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were coded as positive history of alcoholism in a second-degree relative; and all other response options were coded as family history negative. Of those who endorsed having an alcoholic relative, 54% had (at least one) first-degree alcoholic relative and 39% had (at least one) second-degree alcoholic relative (but no first-degree relatives). Given the high endorsement rate of alcoholism in first-degree relatives (presumably as the result of the imprecisely defined term alcoholic), we chose to create an extreme-groups family history variable to maximize the differential between those whose family history connoted some index of risk versus those who truly had an absence of alcoholism in their family. We defined the high-risk group as including those who indicated positive history of alcoholism among more than one relative, (at least) one of which was a first-degree relative. The low-risk group was represented by those who did not endorse having an alcoholic relative and those whose alcoholic relatives failed to meet criteria for being first or second degree.

This new variable was assessed on 65% of the sample (n = 2,593; 21% of which are henceforth referred to as family history positive; 79% which are henceforth referred to as family history negative). We compared those 2,593 respondents with a family history (FH) variable to the 1,410 without on a number of Time 1 demographic and drinking-related variables, including gender, race, age, frequency of drinking, frequency of heavy drinking, quantity of alcohol use, and number of symptom domains endorsed. There was no difference in FH variable status on gender, race, age, frequency of drinking, frequency of heavy drinking, or quantity of alcohol consumed. However, those with a FH variable did endorse more alcohol dependence symptoms at Time 1 than those without, F(1, 4001) = 7.72, p < .01 (M = 13.35 for those with FH vs. M = 13.23 for those without FH). The effect size for this finding, however, is very low (Cohen’s d = .09), and we conclude that the sample on which we had family history status was representative of the full sample.

Analytic Strategy

We identified class membership based on alcohol dependence symptoms for both Time 1 (1989) and Time 2 (1994) via latent class analysis (LCA) using Mplus Version 2.13 (L. K. Muthen & Muthen, 2001, Nelson, Heath, & Kessler, 2002). LCA is a categorical analog to factor analysis, but the observed variables and the latent variable are both categorical in nature (McCutcheon, 1987). However, instead of identifying a number of factors that account for all of the variables, LCA is used to identify a number of latent classes that accounts for the response profiles of all of the respondents. Specifically, the latent classes represent particular groups of individuals who display similar patterns of alcohol dependence symptoms. The observed variables represent the endorsement (1) or failure to endorse (0) a particular symptom. In the present case with seven dichotomous variables, there are 128 (27) possible response profiles. Most likely, however, a much smaller number of latent class constructs are necessary to explain the observed patterns. Parameters of interest include class prevalences and the respondent’s likelihood of endorsing a given symptom (symptom endorsement probabilities) given membership in a particular class. Symptom endorsement probabilities are akin to factor loadings in exploratory factor analysis. Model fit is evaluated using information criteria fit indices (i.e., Bayesian information criterion [BIC], Schwarz, 1978 and Akaike’s information criterion [AIC], Akaike, 1987), such that lower numbers indicate better-fitting models. Neuman et al. (1999) also proposed a number of considerations for adjudicating among alternative latent class models. First, they recommend considering change in fit while emphasizing parsimony. Additionally, Neuman et al. suggest the following criteria for model fit: the reasonableness of the model relative to the study’s research questions and/or previous findings (i.e., theoretical interpretability), the generalizability of the model to other populations (e.g., class prevalences that are likely to be practically meaningful), and the sample sizes used (i.e., considering issues of statistical vs. practical invariance).

After identifying the most reasonable number of latent classes given the data, we examined the transition among classes using latent transition analysis (LTA), a dynamic latent variable model for discrete longitudinal data. Using WinLTA Version 3.0 (Collins, Lanza, Schafer, & Flaherty, 2002), we extracted latent statuses from unique response profiles of endorsements based on our seven discrete alcohol dependence symptoms assessed on two measurement occasions. Again, symptom endorsement probabilities, which are termed “unconditional measurement parameters” in LTA, represent the probability of endorsing a given item. These parameters were constrained to be identical across time within a given item. Transition probabilities (i.e., probabilities of transitioning from one class to another) were estimated for the full sample and also for subgroups to permit group comparison. Data augmentation, a Gibbs sampling-based procedure (Collins, Lanza, & Schafer, 2002), was used to estimate standard errors to obtain 95% confidence intervals on the parameters. Overall model fit was estimated using a likelihood-ratio chi-square, denoted G2, which compares predicted and observed response pattern frequencies, using the following formula for degrees of freedom: the number of response patterns minus (the number of estimated parameters + 1). For comparison across subgroups, we compared nested models using a difference test where ΔG2 = (Model A G2) − (Model B G2). Given the large sample size in the current study (N = 4,003), we note that statistically significant differences in model fit could be trivial in absolute magnitude. As such, we looked for “practical invariance” by examining the size of the ΔG2 relative to the degrees of freedom (df), concluding practical invariance for ΔG2 values that were close to the df (i.e., a ratio of 2:1 for df: ΔG2). Models were estimated using listwise deletion.

Results

Latent Class Analysis

We first report the LCA on the seven symptoms at Time 1, and another LCA for the seven symptoms at Time 2, to determine the critical number of latent classes to use in the LTA. We examined two- through five-class solutions (the six-class model would not converge). We evaluated the models with reference to information criteria fit indices (AIC, BIC) as well as theoretical interpretability, class prevalence, and parsimony. For the Time 1 model, the three-class solution was best according to BIC, theoretical interpretability, and class prevalence (see Table 3, left panel). Although AIC favored the four-class solution, the largest change in value for both AIC and BIC occured between the two-class and three-class solutions. For the three-class solution, Class 1 (3%) was characterized by high symptom endorsement probabilities for nearly all symptoms (endorsement rates >78% for all symptoms except for failed attempts and give up activities), and is termed the “severe alcohol dependence” class. Class 2 (16%) was characterized by high endorsement probabilities for using more or for longer than intended and tolerance and is termed the “mild alcohol dependence” class. Class 3 (81%) was characterized by near-zero endorsement probabilities for all symptoms (with using more or for longer than intended and tolerance endorsed by 7.6% and 6.1% of the sample, respectively, and the rest of the symptoms endorsed by <2% of the sample) and is termed the “no dependence” class.

Table 3.

Fit Indices and Class Prevalences for Latent Class Analyses of Alcohol Dependence Symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2

| Time 1 |

Time 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | Class prevalences | AIC | BIC | Class prevalences | |

| Two-class | 14266.30 | 14360.72 | 0.15 0.85 |

14568.00 | 14662.42 | 0.15 0.85 |

| Three-class | 14105.66 | 14250.44 | 0.03 0.16 0.81 |

14298.06 | 14442.84 | 0.04 0.19 0.77 |

| Four-class | 14104.59 | 14299.73 | 0.02 0.03 0.16 0.79 |

14287.55 | 14482.69 | 0.02 0.04 0.16 0.77 |

| Five-class | 14108.86 | 14354.35 | 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.14 0.80 |

14284.74 | 14530.23 | 0.01 0.03 0.09 0.10 0.77 |

| Six-class | ||||||

| Model will not converge | Model will not converge | |||||

Note. N = 4,003. AIC = Akaike’s information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

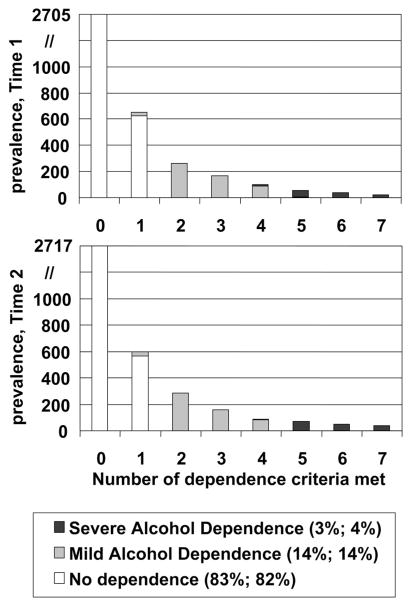

For the Time 2 data, we again selected a three-class model based on BIC, theoretical interpretability, and class prevalence (see Table 3, right panel). The classes were very similar to those at Time 1 but with a slightly lower prevalence for the no dependence group (81% at Time 1 vs. 77% at Time 2), a slightly higher prevalence for the mild alcohol dependence class (19% vs. 16%), and a slightly higher prevalence for the severe alcohol dependence class (4% vs. 3%). The symptom endorsement probabilities were nearly identical to those at Time 1. To validate our latent class variable, we examined the association between class membership and the alcohol dependence symptoms. We assigned respondents to classes on the basis of their most likely class membership.2 Examination of these posterior probabilities revealed very good classification for both Time 1 (M = 0.94; SD = 0.09; range = 0.50–0.995) and Time 2 (M = 0.93; SD = 0.11; range = 0.50–0.995). Next, we calculated the number of symptoms respondents endorsed and examined the number of symptoms endorsed as well as whether the respondent met three or more criteria for alcohol dependence (diagnostic threshold) as a function of class.3 For Time 1 classes and Time 1 symptoms, individuals in the no dependence class (83%) endorsed zero or one symptoms (mode = 0; none endorsed three or more criteria). Individuals in the mild alcohol dependence class (14%) endorsed between one and five symptoms (mode = 2; 47% endorsed three or more criteria). Finally, those in the severe alcohol dependence class (3%) endorsed between four and seven symptoms (mode = 5; 100% endorsed three or more criteria). The pattern of findings was very similar at Time 2 Figure 1 shows the number of symptoms endorsed as function of class membership for Time 1 (top panel) and Time 2 (bottom panel); note that there is very little overlap between classes (i.e., very few of those who endorsed one symptom were in the mild alcohol dependence class; like wise, very few of those who endorsed four symptoms were in the severe alcohol dependence class).

Figure 1.

Number of symptoms endorsed by class membership for Time 1 and for Time 2. N = 4,003. The top panel includes symptoms at Time 1 and class membership from the Time 1 latent class analysis; the bottom panel includes symptoms at Time 2 and class membership from the Time 2 latent class analysis. Class prevalences in the legend refer to Time 1; Time 2.

Latent Transition Analysis

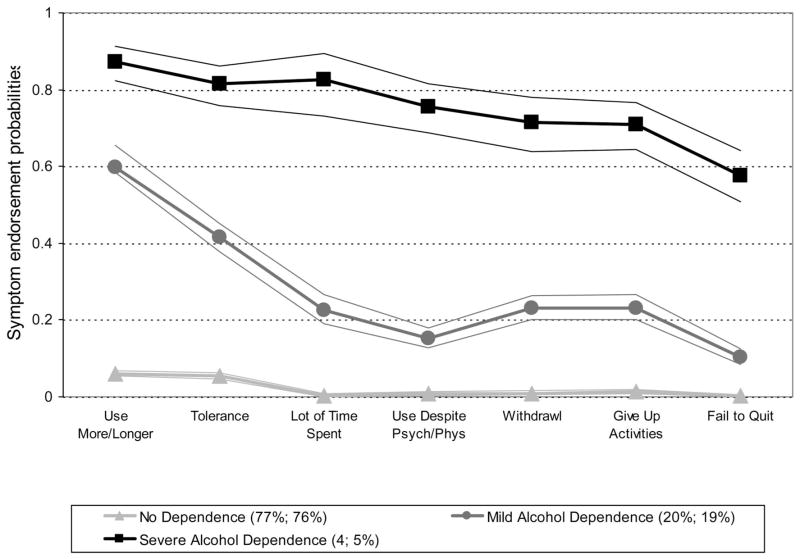

We fit a three-class (henceforth termed status) LTA model to our seven alcohol dependence symptoms, G2 (16,354, N = 4,003) = 2,771.78. Figure 2 presents the symptom endorsement probabilities (constrained to be identical across time)4 and their 95% confidence intervals for each symptom by the three latent statuses, which included (1) a no dependence status (77% of 4,003 participants at Time 1), (b) a mild alcohol dependence status (20%), and (c) an alcohol dependence status (4%). These statuses corresponded to the classes identified in the cross-sectional latent class analyses.

Figure 2.

Symptom endorsement probabilities (constrained to be identical across time) and their 95% confidence intervals for each symptom by the three latent statuses. Note. N = 4,003. Class prevalences in the legend refer to Time 1; Time 2.

As noted in our previous work using LTA (Jackson et al., 2001), interpretation of the transition probability parameters requires consideration of the proportion of respondents that belong to a given latent status at Time 1 (i.e., base rates) because in the LTA, transition probabilities are conditional on initial (Time 1) latent status. This is especially true when comparing transition probabilities that do not have the same base rate (i.e., transition probabilities that are not in the same row of the transition probability matrix). To address this issue, we provide numbers of individuals in our transition probability matrices and recommend that the reader also consider these numbers when comparing transition probabilities.

Stabilities (i.e., values on the diagonal in Table 4) were very high for the no dependence status (89%, n = 2,736) and were moderate in magnitude for the mild alcohol dependence status (50%, n = 396) and the severe alcohol dependence status (45%, n = 67). We were specifically interested in examining progression and regression across latent classes of alcohol dependence. There were as many individuals who regressed (n = 398) as progressed (n = 411). However, when we consider base rates, regression appears to be much more normative. Of the (estimated) 3,859 individuals who could have progressed (i.e., nondiagnosers and those with mild alcohol dependence at Time 1), there were 411 individuals (from Table 4, above the diagonal, 286 + 49 + 76), or 11%, who transitioned into a more severe alcohol dependence status. Conversely, of the 937 individuals who could regress (i.e., those with mild or severe alcohol dependence at Time 1), there were 398 individuals (below the diagonal, 317 + 2 + 79), or 42%, who transitioned into a less severe status. In sum, nondependent respondents tended to have high stability; those with mild alcohol dependence tended to either remain so or to regress to nondependent, and those with severe alcohol dependence were slightly more likely to regress (to mild alcohol dependence) than to persist.

Table 4.

Conditional Latent Transition Probability Estimates Shown as Row Percentages, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Estimated Cell n

| Time 1 Ages 24–32 years |

Time 2 Ages 29–37 years |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dependence | Mild acohol dependence | Severe alcohol dependence | Marginal | |

| No dependence | 89% | 9% | 2% | 77% |

| 87–91% | 7–12% | 1–2% | 74–80% | |

| 2736 | 286 | 49 | 3070 | |

| Mild alcohol dependence | 40% | 50% | 10% | 20% |

| 35–46% | 43–56% | 7–13% | 17–22% | |

| 317 | 396 | 76 | 789 | |

| Severe alcohol dependence | 2% | 53% | 45% | 4% |

| 0.4–21% | 37–65% | 34–56% | 3–4% | |

| 2 | 79 | 67 | 148 | |

| Marginala | 76% | 19% | 5% | |

| 3055 | 761 | 192 | 4,003 | |

Note. N = 4,003.

Standard errors are not computed for Time 2 marginals in WinLTA.

Cross-Group Comparisons

We conducted a series of cross-group analyses in which initial statuses and transition probabilities across age cohort, gender, race, and family history of alcoholism were compared. Preliminary analyses either failed to show, or showed only very minimal, differences in latent class structure across age cohort, gender, race, and family history.5 However, as would be expected, there were seeming differences in the prevalence of the various dependence classes as a function of group membership with younger age, negative family history of alcoholism, female sex, and European American ethnicity associated with membership in the nondependent class. These findings and those regarding between group differences in transition probabilities are described herein.

Age cohort

The age range of the NLSY dataset we were working with was, from a young adult developmental perspective, quite broad (ages 24 –32 at Time 1 and ages 29 –37 at Time 2). We first examined whether initial transition statuses and transition probabilities significantly differed across age cohort. First, initial statuses across group were freely estimated (see marginal rows in Table 5 for status probabilities for young, middle, and older). Next, we constrained initial statuses to be identical across cohort and found that model fit was significantly different across groups, ΔG2 (4, N = 4,003) = 27.54, p < .001, indicating that initial alcohol dependence statuses differed across cohort status. Visual inspection of Table 5 suggests that the young cohort was most likely and the older cohort least likely to be in the mild or severe alcohol dependence statuses. It is helpful to consider the confidence intervals (see the second row of each cell entry in Table 5) because they reflect the degree of uncertainty associated with each parameter (Hyatt, Collins, & Schafer, 1999). Comparison of confidence intervals reveals the extent to which parameters significantly differ from one another (i.e., overlapping confidence intervals indicate nonsignificant group differences). For the no dependence and mild alcohol dependence statuses, the confidence intervals for the marginal frequencies for the young cohort did not overlap with those of the middle or older cohorts (which did overlap with each other), suggesting that any group differences that did exist were due to the younger respondents being different from the rest of the respondents.

Table 5.

Conditional Latent Transition Probability Estimates for Three Cohorts (Young, Middle, Older) Shown as Row Percentages, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Estimated Cell n

| Time 1 Ages 24–32 years |

Time 2 Ages 29–37 years |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dependence |

Mild alcohol dependence |

Severe alcohol dependence |

Marginal |

|||||||||

| Young | Middle | Older | Young | Middle | Older | Young | Middle | Older | Young | Middle | Older | |

| No dependence | 88% | 88% | 92% | 10% | 11% | 6% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 70% | 78% | 81% |

| 85–92% | 86–91% | 89–95% | 6–14% | 8–12% | 3–10% | 1–4% | 1–2% | 1–4% | 68–75% | 76–82% | 78–85% | |

| 801 | 1113 | 805 | 95 | 138 | 57 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 912 | 1269 | 876 | |

| Mild alcohol dependence | 35% | 43% | 44% | 54% | 46% | 50% | 11% | 11% | 6% | 25% | 18% | 17% |

| 28–41% | 36–52% | 32–55% | 46–61% | 36–54% | 41–61% | 7–18% | 7–18% | 2–14% | 21–27% | 15–20% | 12–19% | |

| 114 | 127 | 79 | 174 | 137 | 91 | 35 | 32 | 10 | 322 | 296 | 180 | |

| Severe alcohol dependence | 0% | 5% | 0% | 59% | 46% | 53% | 41% | 50% | 47% | 5% | 4% | 3% |

| 0–24% | 0–35% | 0–39% | 43–74% | 28–70% | 26–73% | 24–55% | 27–66% | 24–69% | 3–6% | 3–5% | 2–4% | |

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 32 | 15 | 24 | 30 | 14 | 59 | 60 | 29 | |

| Marginala | 71% | 76% | 82% | 24% | 19% | 15% | 6% | 5% | 4% | |||

| 916 | 1243 | 884 | 304 | 307 | 163 | 74 | 81 | 38 | 1293 | 1625 | 1085 | |

Note. N = 4,003. Young n = 1,293; middle n = 1,625; older n = 1,085.

Standard errors are not computed for Time 2 marginals in WinLTA.

Bearing these marginal frequency differences in mind, we then examined whether transition probabilities significantly differed across cohort. Transition probabilities across cohort were freely estimated (see Table 5 for transition probabilities and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each cohort). Next, we estimated a model in which all transition probabilities were constrained to be identical across cohort. The χ2 difference test was nonsignificant, indicating invariance across cohort, ΔG2 (12, N = 4,003) = 12.39, ns. That is, although prevalence of status membership differed over the three cohorts, transitions among alcohol dependence statuses did not significantly differ across cohort status. Consistent with this finding, none of the cells in the transition probability table had nonoverlapping confidence intervals between young, middle, and older respondents. Given the few differences observed in the model parameters across the three levels of cohort, we felt that it was defensible to collapse all subsequent analyses over the full sample (rather than examining subgroups by cohort).

Gender

Next, we examined whether initial transition statuses and transition probabilities significantly differed across gender. First, initial statuses across group were freely estimated (see marginal rows in Table 6 for status probabilities for men and women). Next, we constrained initial statuses to be identical across gender and found that model fit was significantly different, ΔG2 (2, N = 4,003) = 82.71, p < .001, suggesting that the prevalence of initial alcohol dependence statuses was different for men and women. Specifically, Table 6 shows that women were more likely to be in the no dependence and less likely to be in the mild and severe alcohol dependence statuses than men (confidence intervals for these Time 1 marginals were nonoverlapping between men and women; see Table 6).

Table 6.

Conditional Latent Transition Probability Estimates for Men and Women Shown as Row Percentages, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Estimated Cell n

| Time 1 Ages 24–32 years |

Time 2 Ages 29–37 years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dependence |

Mild alcohol dependence |

Severe alcohol dependence |

Marginal |

|||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| No dependence | 85% | 93% | 12% | 6% | 2% | 1% | 70% | 85% |

| 82–88% | 91–96% | 10–15% | 4–9% | 1–4% | 0–2% | 68–74% | 83–88% | |

| 1445 | 1267 | 212 | 80 | 37 | 11 | 1694 | 1357 | |

| Mild alcohol dependence | 36% | 51% | 53% | 43% | 11% | 6% | 25% | 13% |

| 31–45% | 38–59% | 44–59% | 33–57% | 7–15% | 2–16% | 22–27% | 10–14% | |

| 219 | 102 | 315 | 87 | 65 | 12 | 599 | 201 | |

| Severe alcohol dependence | 4% | 0% | 50% | 57% | 46% | 43% | 5% | 2% |

| 0–37% | 0–22% | 32–64% | 35–74% | 36–58% | 25–62% | 4–6% | 2–3% | |

| 4 | 0 | 57 | 22 | 52 | 16 | 113 | 38 | |

| Marginala | 69% | 86% | 24% | 12% | 6% | 2% | ||

| 1668 | 1369 | 584 | 189 | 154 | 39 | 2406 | 1597 | |

Note. N = 4,003. Men n = 2,406; women n = 1,597.

Standard errors are not computed for Time 2 marginals in WinLTA.

We examined whether transition probabilities significantly differed across gender. Transition probabilities across sex were freely estimated (see Table 6 for transition probabilities and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for men and women). Next, we estimated a model in which all transition probabilities were constrained to be identical across gender. Model fit was significantly different, ΔG2 (6, N = 4,003) = 40.80, p < .001, suggesting that transitions among alcohol dependence statuses were different for men and women. Women in the no dependence status had greater stability than men (shown as nonoverlapping confidence intervals in this cell). Also, women were less likely to progress to a more severe status, particularly the transition from no dependence to mild alcohol dependence. Although women appeared to be more likely to regress to a less severe status than men, the confidence intervals for these transitions were overlapping.

Race

We also examined the extent to which initial transition statuses and transition probabilities significantly differed across race. As with cohort and gender, initial statuses across group were first freely estimated (see marginal rows in Table 7 for status probabilities for White, Black, and Hispanic subjects), and then initial statuses were constrained to be identical across race. Change in model fit indicated invariance, ΔG2 (4, N = 4,003) = 4.42, ns, suggesting that initial alcohol dependence statuses did not significantly differ across race.

Table 7.

Conditional Latent Transition Probability Estimates for Hispanic, Black, and White Respondents Shown as Row Percentages, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Estimated Cell n

| Time 1 Ages 24–32 years | Time 2 Ages 29–37 years |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dependence |

Mild alcohol dependence |

Severe alcohol dependence |

Marginal |

|||||||||

| Hisp. | Black | White | Hisp. | Black | White | Hisp. | Black | White | Hisp. | Black | White | |

| No dependence | 87% | 85% | 92% | 12% | 13% | 7% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 76% | 76% | 77% |

| 83–91% | 82–87% | 90–94% | 7–15% | 9–16% | 5–8% | 1–4% | 1–4% | 1–2% | 72–81% | 74–80% | 75–80% | |

| 482 | 657 | 1591 | 64 | 98 | 123 | 9 | 17 | 21 | 555 | 773 | 1736 | |

| Mild alcohol dependence | 46% | 32% | 42% | 40% | 56% | 51% | 14% | 12% | 7% | 20% | 19% | 20% |

| 33–55% | 20–47% | 33–50% | 29–54% | 41–68% | 42–61% | 8–25% | 8–20% | 4–11% | 15–23% | 15–22% | 18–22% | |

| 66 | 62 | 190 | 57 | 108 | 232 | 20 | 23 | 33 | 143 | 193 | 454 | |

| Severe alcohol dependence | 2% | 6% | 0% | 50% | 40% | 61% | 48% | 54% | 39% | 5% | 4% | 3% |

| 0–37% | 0–44% | 0–20% | 23–76% | 21–65% | 41–75% | 20–73% | 31–72% | 25–56% | 3–6% | 3–6% | 2–4% | |

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 17 | 18 | 43 | 16 | 24 | 27 | 34 | 44 | 70 | |

| Marginala | 75% | 71% | 79% | 19% | 22% | 18% | 6% | 6% | 4% | |||

| 549 | 722 | 1781 | 138 | 224 | 398 | 45 | 64 | 81 | 732 | 1010 | 2261 | |

Note. N = 4,003. Hispanic n = 732; Black n = 1,010; White n = 2,261. Hisp. = Hispanic.

Standard errors are not computed for Time 2 marginals in WinLTA.

Again, we next examined the extent to which transition probabilities significantly differed across race. Transition probabilities across race were freely estimated (see Table 7 for transition probabilities for Hispanic, Black, and White respondents), and then transition probabilities were constrained to be identical across race. Model fit was significantly different, ΔG2 (12, N = 4,003) = 26.39, p < .01, suggesting that transitions among alcohol dependence statuses were significantly different for Hispanic, Black, and White respondents. Upon further inspection of Table 7, it appeared that White respondents exhibited different transition probabilities than the other two racial groups. For example, White respondents in the no dependence status exhibited higher stabilities (95% confidence intervals were nonoverlapping between Whites and Black respondents) Although White respondents in the severe alcohol dependence status exhibited lower stabilities than Hispanic or Black respondents, confidence intervals were overlapping because of small cell sizes. White respondents also were less likely to progress to a more severe alcohol dependence status, particularly the transition from no dependence to mild dependence (confidence intervals were nonoverlapping between Whites and Blacks).

We constrained the transition probabilities of Black and Hispanic respondents to be identical to each other and allowed transition probabilities to be freely estimated for White respondents. Model fit was not significantly different, ΔG2 (6, N = 4,003) = 4.50, ns, suggesting that transitions among alcohol dependence statuses did not significantly differ between Black and Hispanic respondents, but both groups together differed from White respondents.

Family history

Finally, we examined whether initial transition statuses and transition probabilities significantly differed across our extreme family history groups. As with previous subgroup analyses, initial statuses across group were freely estimated (see marginal rows in Table 8 for status probabilities for family history positive and negative) Next, we constrained initial statuses to be identical across family history status and found that model fit was significantly different, ΔG2 (2, N = 2,593) = 45.25, p < .001, suggesting that initial alcohol dependence statuses were different for family history positive and negative individuals. Visual inspection of Table 8 shows that family history negative individuals were more likely to be in the no dependence and less likely to be in the mild and severe alcohol dependence statuses (with nonoverlapping confidence intervals for the no dependence and severe alcohol dependence statuses).

Table 8.

Conditional Latent Transition Probability Estimates for Family History Negative (FH−) and Family History Positive (FH+) Respondents Shown as Row Percentages, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Estimated Cell n

| Time 1 Ages 24–32 years |

Time 2 Ages 29–37 years |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dependence |

Mild alcohol dependence |

Severe alcohol dependence |

Marginal |

|||||

| FH− | FH+ | FH− | FH+ | FH− | FH+ | FH− | FH+ | |

| No dependence | 88% | 87% | 10% | 12% | 2% | 1% | 79% | 66% |

| 85–91% | 83–93% | 8–13% | 6–16% | 1–3% | 0–11% | 77–83% | 60–72% | |

| 1432 | 307 | 170 | 41 | 29 | 5 | 1631 | 352 | |

| Mild alcohol dependence | 43% | 34% | 49% | 51% | 8% | 16% | 18% | 25% |

| 34–52% | 20–44% | 39–58% | 39–65% | 5–13% | 9–29% | 15–20% | 19–31% | |

| 162 | 45 | 184 | 68 | 30 | 21 | 377 | 135 | |

| Severe alcohol dependence | 0% | 0% | 67% | 38% | 33% | 62% | 2% | 9% |

| 0–39% | 0–24% | 44–80% | 19–60% | 17–52% | 39–77% | 2–4% | 6–12% | |

| 0 | 0 | 35 | 18 | 17 | 29 | 51 | 47 | |

| Marginala | 78% | 66% | 19% | 24% | 4% | 10% | ||

| 1594 | 352 | 389 | 127 | 76 | 55 | 2059 | 534 | |

Note. N = 2,593. FH− n = 2,059; FH+ n = 534.

Standard errors are not computed for Time 2 marginals in WinLTA.

Finally, we examined the extent to which transition probabilities significantly differed across family history status. Transition probabilities across family history status were freely estimated (see Table 8 for transition probabilities and 95% confidence intervals). Next, we estimated a model in which all transition probabilities were constrained to be identical across family history status. Model fit was not significantly different, ΔG2 (6, N = 2,593) = 10.44, ns, suggesting that transitions among alcohol dependence statuses were not different for family history positive versus negative respondents. To support this finding, none of the cells in the transition probability table had nonoverlapping confidence intervals between family history positive and negative respondents.

Discussion

Our initial cross-sectional latent class models, used to determine the number of classes for use in the LTA, replicated the general trend toward a severity gradient observed in previous cross-sectional LCAs of alcohol-related consequences in age-heterogeneous samples (Bucholz et al., 1996) and a clinical sample of adolescents (Chung & Martin, 2001). This result is noteworthy given that our sample is relatively homogeneous with regard to age and suggests that the alcohol DSM–IV dependence construct is valid for individuals at this particular developmental period (i.e., early to middle adulthood). These findings provide additional evidence to support the notion of alcohol dependence as a syndrome that lies on a continuum of severity (Bucholz et al., 1996; Hasin, Muthen, Wisnicki, & Grant, 1994) as proposed by Edwards and Gross (1976). Further, these results are informative because they illustrate which symptoms distinguish mild (e.g., tolerance, using more or for longer than intended) from severe alcohol dependence (e.g., withdrawal, continued use despite recurrent physical/psychological problems, unsuccessful efforts to quit or cut down).

Consequently, our findings are not consistent with the current DSM–IV strategy of specifying or subtyping alcohol dependence on the basis of physiological versus nonphysiological dependence. Such a distinction has historically been used to designate a more versus less severe manifestation of dependence based upon signs and symptoms of neuroadaptation. In this sample, however, mild dependence was best exemplified by tolerance and using more or for longer than intended. In this same way, these data are inconsistent with previous research on the value of the physiological versus nonphysiological distinction, unless we restrict determination of physiological dependence to the presence of withdrawal symptomatology (Schuckit et al., 1998). The meaning of reported tolerance in the absence of other more “severe” dependence symptoms is ambiguous in this sample (given the identification of a mild dependence class that tended to persist only moderately over time). This finding echoes results from our previous research that challenges the relative importance of physiological symptom atology as it has been historically conceptualized in young adults (O’Neill & Sher, 2000) and adolescents (Martin, Langenbucher, Kaczynski, & Chung, 1996) but also high lights current concerns about assessing tolerance in young drinkers (e.g., high rates of endorsing tolerance symptoms by young drinkers in the absence of other severe alcohol problems; Chung, Martin, Winters, & Lanbenbucher, 2001; Martin & Winters, 1998) using the type of self-report items used here and in most studies. This result is inconsistent with the view of physiological dependence (as indicated by tolerance or withdrawal) as distinctly less prevalent and more severe than other alcohol-related disability. This conclusion must be tempered, however, because tolerance questions typically asked in population surveys may not adequately assess tolerance in the clinical sense and may reflect a more benign characteristic. This is supported by the recent work using item response theory analysis by Kahler and colleagues (Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005; Kahler, Strong, Read, Palfai, & Wood, 2004) showing that tolerance sensitive of relatively mild levels of alcohol problems and expected to appear early in the sequence of alcohol problems. Clearly, assessing tolerance by self-report is a major challenge (O’Neill & Sher, 2000).

Our results indicating that withdrawal strongly distinguishes the severe from the moderate or no-dependence classes, on the other hand, are consistent with a previously specified model of dependence that was proposed by Langenbucher and colleagues (2000) that emphasizes withdrawal (but not tolerance) symptoms in the dependence construct. In this proposed revision toward DSM–V, withdrawal symptoms are pathognomic (i.e., both necessary and sufficient) for a dependence diagnosis. In the models re ported herein, withdrawal symptoms, but not tolerance symptoms, were representative of severe dependence. Yet, we also observed that continued use despite recurrent physical/psychological problems and unsuccessful efforts to quit or cut down (and, to a lesser extent, giving up important activities because of drinking) were also indicative of severe alcohol dependence. Findings based on item response theory analysis by Krueger et al. (2004) and Langenbucher al. (2004) also suggest that continued use despite physical/psychological problems and spending a great deal of time activities related to drinking (in addition to withdrawal) are all highly discriminatory indices of severe dependence. As such, our findings are consistent with recent work by Langenbucher and others highlighting the severity of withdrawal relative to tolerance and suggesting the potential for other symptoms to increase our ability to distinguish abuse from dependence.

Our findings suggest that although there is nontrivial movement back and forth among levels of severity of alcohol dependence (observed in the transitions among our graded latent classes), with a demonstration that persistence, progression, and regression all exist, we see greater evidence of chronicity and remission than of progression, even at this relatively young age. On the basis of population based epidemiology from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (i.e., NLAES) and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (i.e., NESARC), we would expect that pattern to be even more pronounced in the early 20s. Unfortunately, the NLSY cohort data did not include measures of alcohol dependence until after most participants had already passed through their peak hazard rates for developing alcohol dependence. The most clearly progressive pattern (i.e., transitioning from nondependence into a dependence class) was observed with no greater frequency than a regressive pattern (i.e., transitioning from a dependence class to nondependence), and when baserates were considered, the percentage of regression (42%) far exceeded the percentage of progression (11%), supporting the cross-sectional epidemiological work showing an age-graded decline in alcohol dependence over adulthood (e.g., Dawson et al., 2004; Grant & Harford, 1994; Hasin & Grant, 2004). Although Hasin et al. (1990, 1997) primarily showed chronicity of alcohol dependence, they observed a sizable minority of participants who remitted, consistent with our own findings. Contrary to the popular characterization of alcoholism as recalcitrant, our results suggest that “natural” and/or treatment-related recovery may be closer to the norm than the exception in the general population of drinking adults with alcohol-related symptoms. These findings are consistent with evidence suggesting that many adults with alcohol problems remit without the aid of professional intervention (Sobell, Cunningham, & Sobell, 1996; Watson & Sher, 1998).

Perhaps more critically, our findings indicate support for the notion of alcoholism as persistent, consistent with the literature revealing relative chronicity of alcohol dependence (Hasin et al., 1997; Schuckit et al., 2000). Classes whose endorsement probabilities would be consistent with an alcohol dependence diagnosis at both time points were observed with some frequency (n = 463), and the prevalence of respondents classified in the no dependence, mild dependence, and severe dependence classes was stable during the 5-year interval. Clearly, many people in this sample struggle with alcohol problems that extend over early and middle adulthood.

Some caveats are in order. The relative prevalence of progression versus regression will vary highly as a function of stage of development, and one might expect that individuals who are assessed in early adolescence to show greater progression than is observed in the current study. We also must bear in mind that assessments do not account for alcohol involvement before ages 24 through 32 years. Clearly, Time 1 is not indicative of a true baseline. Without additional observations of alcohol dependence symptomatology before Time 1, we cannot equivocally evaluate the degree to which alcohol dependence exhibits progression or desistence. The persistently severe dependence class we observed in the current study may have experienced mild dependence symptomatology (e.g., tolerance, use more or for longer than intended) before the assessments used in the current study. Individuals who report alcohol dependence during ages 18–24 years have been observed to be more persistent in their dependence relative to individuals in older age groups (Grant, 1997). For this reason, it seems reasonable to expect that a non-negligible percent of those marked by severe alcohol dependence exhibited mild dependence symptomatology before study baseline.

Relatedly, the absence of a follow-up beyond Time 2 precludes definitive conclusions about syndrome persistence. The past-year interval in the current study (rather than a past 5-year interval that would capture the period since Time 1) would not represent the more short-lived symptoms that emerged and remitted during the follow-up interval, which might have led us to underestimate rates of progression (if the symptoms were indicative of more severe alcohol dependence) or persistence (if the symptoms were consistent with the original level of alcohol dependence). In addition, it is certainly possible that some of the regression we have observed is due to those with more severe alcohol dependence selecting (either voluntarily or involuntarily) abstinence or controlled drinking and, if presented with the opportunity to drink, their symptoms of dependence may indeed progress in a characteristic manner. Finally, patterns of problematic alcohol involvement observed in a community sample such as the NLSY may differ from that observed in treatment and other clinical samples in ways that may influence the generalizability of results from one setting to the other.

Differences as a Function of Subgroup

Race

Our data suggest that the latent structure of DSM–IV alcohol dependence is consistent across racial groups at the level of the person, which extends work by Caetano and colleagues (Caetano & Kaskutas, 1995; Caetano & Schafer, 1996) demonstrating that the latent structure of DSM–IV alcohol dependence is invariant across ethnic group at the level of the symptom (i.e., factor structure). These data suggests that these groups typically do not present with a manifestation of alcohol dependence that is distinct in kind from their peers and is consistent with the characterization of alcohol dependence as continuous in both majority and nonmajority groups. The only exception to this pattern was that Black respondents in the severe alcohol dependence class were more likely to endorse items referencing unsuccessful efforts to quit or cut down whereas their White counterparts with both mild and severe alcohol dependence were more likely to endorse symptoms reflecting impaired control. These patterns suggest that Black respondents may have more difficulty making and maintaining sustained quit attempts whereas White respondents experience more challenges around controlling the amounts of alcohol they consume during a circumscribed drinking occasion.

We observed relative consistency in initial class prevalences among the three ethnic groups. However, nondependent White respondents were more likely to remain so and were less likely to progress to mild dependence than were Black respondents. Epidemiologic data on changes in heavy drinking patterns across racial groups suggest that White respondents report heavier alcohol involvement at earlier ages than their minority peers (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1994) and that, correspondingly, White respondents report a decrease in heavy drinking by this stage of life whereas their Black and Hispanic counterparts are more stable in their heavy drinking (Caetano & Kaskutas, 1995). Our own data support the idea that by midadulthood, alcohol dependence may be observed less frequently in White than in Black and Hispanic respondents. These findings highlight the potential need for more targeted prevention (e.g., screening toward early identification of problem drinkers) and greater access to treatment in minority communities.

Age cohort

The results of the age cohort analyses indicated that, at Time 1, the younger cohort was less likely to be nondependent and more likely to be in the mild dependence class than the other two cohorts. This result is consistent with the epidemiologic literature in which higher rates of alcohol problems and alcohol use disorders are observed in younger relative to older adults (e.g., Grant, 1997; Grant & Harford, 1994; Hasin & Grant, 2004). However, these between-subjects findings at Time 1 are somewhat inconsistent with the longitudinal findings which failed to provide a within-subjects replication of the age effect. It is difficult to reconcile this apparent discrepancy. Although it is tempting to hypothesize that this apparent discrepancy is attributable to the specific age distribution of participants with most participants being assessed at the beginning of a developmental period that is characterized by rather stable population prevalences of dependence, we would still expect to see a change in the marginal probabilities for dependence in younger versus older participants; instead, these marginal base rates appear to be relatively stable over the course of 5 years. Although this suggests developmentally persistent cohort differences in prevalences, we are not aware of other data to suggest that such a difference would be operative at this historical point in time. Instead, it seems more likely that these differences are attributable to the specific methodology of the NLSY. Given this caveat, we were unable to observe practical differences in transition probabilities across cohort groups (e.g., younger adults were no more or less likely to progress from mild to severe dependence than older adults). Therefore, we feel confident in generalizing the substantive findings described herein to individuals across the full age group represented in the sample (i.e., individuals ranging in age from 24 to 37 years).

Gender

Per expectation, more men were represented in the affected classes than women. In addition, women were more likely to remain in the no dependence class and, correspondingly, were less likely to progress into the mild dependence class (and likely the severe dependence class, although cell sizes were too low to detect significant differences). Patterns of regression were roughly equivalent in men and women, although men appeared to demonstrate less stability in their patterns of problem manifestation over time.

However, our gender comparisons must be considered in light of recent findings by Chung, Langenbucher, McCrady, Epstein, and Cook (2002) that women drinkers show a later onset of symptoms, the most severe of which are unlikely to appear until they approach midlife. In their clinical sample of women, problems that occur early in the course of alcohol use disorder (e.g., hazardous use, spending a lot of time using) typically occurred 10 to 15 years after the onset of drinking (M = 16). Chung et al. (2002) found that a second “stage” of alcohol use disorder was characterized by social problems, medical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by alcohol, or attempts to quit or cut down on alcohol that typically occurred 15 to 20 years (ages 31 to 36) after onset of drinking. Symptoms of later stages included tolerance, giving up activities to drink, and withdrawal and tended not to onset until after age 36. In contrast, Langenbucher and Chung’s (1995) study using a predominately male sample showed earlier onset of and more rapid escalation through the stages, with all symptoms occurring within 12 years of regular drinking. This research suggests that adequate exploration of chronicity and persistence across men and women may be difficult because the female participants would have yet to pass into the critical period of risk for the most severe alcohol problems.

Family history of alcoholism

Not surprisingly, family history-positive individuals proved more likely to appear in the alcohol dependence statuses at Time 1. These findings are consistent with decades of research demonstrating increased risk of alcohol use problems in relatives of alcoholics (Sher, 1991). Of interest, our latent transition analyses did not find that family history-positive individuals were more or less likely to progress from a less severe class at Time 1 to a more severe class at Time 2, to regress from a more severe class to a less severe class, or to maintain the same status across the two time points. However, earlier work of ours on a younger cohort studying “effect drinking” suggested that those with a family history of alcoholism may be less likely to remit to a less severe status over time (Jackson et al., 2001). Despite the failure to find significant differences in transition probabilities between FH+ and FH− groups, those with a positive family history were approximately twice as likely to progress from mild to severe dependence and to maintain severe dependence classifications during the 5-year study interval, and the odds ratios for severe dependence, relative to no dependence, associated with a positive family history of alcoholism increased from 3.0 to 5.4. Thus, although we could not demonstrate significant family history differences in course with this approach (perhaps because of reduced power, as family history was ascertained on only 65% of the sample), the findings are clearly consistent with greater persistence and progression (and hence, less remission) among those with a positive family history.

Limitations

The relative age homogeneity in our sample allowed us to evaluate alcohol dependence within a particular developmental stage and replicate findings based on age heterogeneous and adolescent samples. Given the recent emphasis on viewing alcoholism from the perspective of developmental psychopathology (Sher & Gotham, 2000), we feel these results make a valuable contribution to the literature despite the threats to generalizability inherent in our sampling. The study’s focus on adults in early to middle adulthood (age 24–32 years at Time 1, age 29–37 years at Time 2) limits our ability to generalize to other developmental periods. However our results are consistent with those reported elsewhere (Bucholz et al., 1996), wherein respondents across the adult life span were assessed.

In addition, self-report data are subject to inherent threats to reliability. Critics have long questioned whether those with alcoholism can accurately report their alcohol consumption and problems, although recent evidence suggests that those with alcoholism (and drinkers in general) do not systematically underreport their alcohol consumption (see Sher & Epler, 2004). Limitations also exist that are associated with prospective data whereby individuals are less likely to report the same problem over time (e.g., negative incidence). Presumably, the use of past-year reports (as opposed to life-time reports) minimizes this concern.

Moreover, although the NLSY data set has numerous strengths, the measurement of dependence is limited and a less comprehensive assessment of indicators of each of the seven DSM–IV criteria for dependence precludes a more nuanced assessment of dependence. Classification of the alcohol dependence items is certainly open to interpretation, and others using the NLSY data have applied the criteria differently (e.g., Harford & Muthen, 2001). Different classifications of the NLSY items may have implications for the findings that are observed. More broadly, there is a need for research to address sensitivity, specificity, and validity of each item for assessing each of the relevant criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence.

In addition, we observed that White, older respondents, and greater-quantity drinkers were less likely to be reinterviewed in 1994. The generalizability of the present study is thus limited with respect to race. However, we note that the NLSY oversampled minorities, which somewhat attenuates this shortcoming. Also, although those who were reinterviewed were less likely to drink in large quantities, we can be reassured that they were similar to the who were lost to follow-up with regard to frequency of drinking, heavy drinking, and number of symptom domains endorsed. To the extent that attrition was related to drinking status, however, we might expect to see underestimates of progression into more severe alcohol dependence and persistence of alcohol dependence, which should be taken into account when evaluating the findings from the present study.

Finally, the NLSY requirement that only respondents who reported having consumed a drink in the past month were administered the alcohol dependence items suggests that our sample drinks more heavily than the general population. Therefore, our findings must be contextualized in the framework of respondents being current drinkers at both times. It is possible that our analysis would fail to capture those who had remitted out of drinking by stopping drinking (i.e., drank at Time 1 but not Time 2) and those who had progressed into drinking (i.e., did not drink at Time 1 but drank at Time 2), leading to an underestimation in the degree of regression or progression. However, examination of past-month drinking in the full sample from Times 1 and 2 (N = 6,814) shows little change in abstention over time (74.7% vs. 74.4% at Times 1 and 2, respectively; ns), which increases our confidence that our findings are relatively robust and are not prone to difference in abstention rates over time.

Summary

Our findings support the move to conceptualize alcohol dependence as predominantly continuous in nature by illustrating a trend toward severity during a developmental period (i.e., early to middle adulthood). Our study extends the results of previous cross-sectional latent class analyses of alcohol symptoms by considering the symptomatology of alcohol dependence prospectively, without reliance upon retrospective reporting and dating of lifetime symptoms and clinically ascertained samples. These data suggest that individuals tend to move both in and out of clinically relevant alcohol dependence (as contrasted with the popular view that individuals will persist in alcoholic drinking over time in the absence of a commitment to abstinence). In our sample, trajectory classes characterized by limited symptom endorsement after indicating extensive symptom endorsement (regression) was nearly as prevalent as classes characterized by limited symptom endorsement before extensive symptom endorsement (progression). These prospective models tended to be generalizable across gender and race and, to a lesser extent, age cohort and family history of alcoholism. Such results are somewhat at odds with the popular characterization of alcoholism as characteristically progressive, persistent, and increasingly severe over time. In sum, the current study describes prospective patterns of past-year symptomatology in a community sample at the person level. The methodological step beyond descriptions based on group averages in the present study provides a new perspective on the degree to which alcohol dependence is fluctuating versus stable and chronic in the population at large.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants K01 AA13938 (PI: K. M. Jackson), R01 AA07231 (PI: K. J. Sher), R37 AA13987 (PI: K. J. Sher), and P50 AA11998 (PI: A. Heath).

Footnotes

Our original goal was to examine all 16 alcohol dependence symptoms available to us from the NLSY assessments in 1989 and 1994. However, a current limitation of WinLTA is that it cannot allocate a vector greater than 2 to the 32nd power, which translates to 16 indicators measured twice. Although we could have estimated our full model, we would not have been able to include a grouping variable. As such, we went with the current strategy of creating composite indicators, operationalizing the seven criteria of DSM–IV alcohol dependence. Ancillary analyses revealed that cross-sectional LCAs using 16 indicators yielded very similar results to the cross-sectional LCAs described herein, with three classes characterized by severe alcohol dependence, mild alcohol dependence, and nondiagnosis.

We also examined number of symptoms endorsed and proportion who met criteria for alcohol dependence using weighted estimates (weighted by probability of group membership). Findings were very similar and, in fact, were identical for the severe alcohol dependence class (indicating that probability of class membership was a perfect 100% for individuals in this class).