Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or liver cancer, is the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, with prevalence 16–32 times higher in developing countries than in developed countries. Aflatoxin, a contaminant produced by the fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus in maize and nuts, is a known human liver carcinogen.

Objectives

We sought to determine the global burden of HCC attributable to aflatoxin exposure.

Methods

We conducted a quantitative cancer risk assessment, for which we collected global data on food-borne aflatoxin levels, consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated foods, and hepatitis B virus (HBV) prevalence. We calculated the cancer potency of aflatoxin for HBV-postive and HBV-negative individuals, as well as the uncertainty in all variables, to estimate the global burden of aflatoxin-related HCC.

Results

Of the 550,000–600,000 new HCC cases worldwide each year, about 25,200–155,000 may be attributable to aflatoxin exposure. Most cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and China where populations suffer from both high HBV prevalence and largely uncontrolled aflatoxin exposure in food.

Conclusions

Aflatoxin may play a causative role in 4.6–28.2% of all global HCC cases.

Keywords: aflatoxin, global disease burden, hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, risk assessment

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or liver cancer, is the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [World Health Organization (WHO) 2008], with roughly 550,000–600,000 new HCC cases globally each year (Ferlay et al. 2004). Aflatoxin exposure in food is a significant risk factor for HCC (Wild and Gong 2010). Aflatoxins are primarily produced by the food-borne fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, which colonize a variety of food commodities, including maize, oilseeds, spices, groundnuts, and tree nuts in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Additionally, when animals that are intended for dairy production consume aflatoxin-contaminated feed, a metabolite, aflatoxin M1, is excreted in the milk (Strosnider et al. 2006).

Aflatoxins are a group of approximately 20 related fungal metabolites. The four major aflatoxins are known as B1, B2, G1, and G2. Aflatoxins B2 and G2 are the dihydro-derivatives of the parent compounds B1 and G1 (Pitt and Tomaska 2001). Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is the most potent (in some species) naturally occurring chemical liver carcinogen known. Naturally occurring mixes of aflatoxins have been classified as a Group 1 human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and has demonstrated carcinogenicity in many animal species, including some rodents, nonhuman primates, and fish [International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS)/WHO 1998)]. Specific P450 enzymes in the liver metabolize aflatoxin into a reactive oxygen species (aflatoxin-8,9-epoxide), which may then bind to proteins and cause acute toxicity (aflatoxicosis) or to DNA to cause lesions that over time increase the risk of HCC (Groopman et al. 2008).

HCC as a result of chronic aflatoxin exposure has been well documented, presenting most often in persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (Wild and Gong 2010). The risk of liver cancer in individuals exposed to chronic HBV infection and aflatoxin is up to 30 times greater than the risk in individuals exposed to aflatoxin only (Groopman et al. 2008). These two HCC risk factors—aflatoxin and HBV—are prevalent in poor nations worldwide. Within these nations, there is often a significant urban–rural difference in aflatoxin exposure and HBV prevalence, with both these risk factors typically affecting rural populations more strongly (Plymoth et al. 2009).

Aflatoxin also appears to have a synergistic effect on hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced liver cancer (Kirk et al. 2006; Kuang et al. 2005; Wild and Montesano 2009), although the quantitative relationship is not as well established as that for aflatoxin and HBV in inducing HCC. Other important causative factors in the development of HCC, in addition to HBV or HCV infection and aflatoxin exposure, are the genetic characteristics of the virus, alcohol consumption, and the age and sex of the infected person (Kirk et al. 2006).

The IPCS/WHO undertook an aflatoxin–HCC risk assessment in 1998 to estimate the impact on population cancer incidence by moving from a hypothetical total aflatoxin standard of 20 ng/g to 10 ng/g (Henry et al. 1999; IPCS/WHO 1998). Assuming that all food containing higher levels of aflatoxin than the standard was discarded and that enough maize and nuts remained to preserve consumption patterns, IPCS/WHO determined that HCC incidence would decrease by about 300 cases per year per billion people, if the stricter aflatoxin standard were followed in nations with HBV prevalence of 25%. However, in nations where HBV prevalence was 1%, the stricter aflatoxin standard would save only two HCC cases per year per billion people. This assessment associated HCC risk with particular doses of aflatoxin; however, these doses do not correspond with actual exposure in different parts of the world, and the two hypothetical values for HBV prevalence, 1% and 25%, were not intended to represent actual HBV prevalence worldwide.

Currently, > 55 billion people worldwide suffer from uncontrolled exposure to aflatoxin (Strosnider et al. 2006). What remains unknown is how many cases of liver cancer can be attributed to this aflatoxin exposure worldwide. Indeed, the Aflatoxin Workgroup (Strosnider et al. 2006), convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO, identified four issues that warrant immediate attention: quantifying human health impacts and burden of disease due to aflatoxin exposure, compiling an inventory of ongoing intervention strategies, evaluating their efficacy, and disseminating the results.

Addressing this first issue is the aim of our study. We compiled available information on aflatoxin exposure and HBV prevalence from multiple nations in a quantitative cancer risk assessment, to estimate the number of HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin worldwide per year. Shephard (2008) estimated population risk for aflatoxin-induced HCC in select African nations; we expand this to include the rest of the world. We briefly describe interventions that can either reduce aflatoxin directly in food or reduce adverse health effects caused by aflatoxin.

Materials and Methods

To perform a quantitative cancer risk assessment for aflatoxin-related HCC, we analyzed extensive data sets by nation or world region: food consumption patterns (of maize and peanuts), aflatoxin levels in maize and peanuts, HBV prevalence, and population size. Risk assessment is the process of estimating the magnitude and the probability of a harmful effect to individuals or populations from certain agents or activities. Four steps are involved in estimation of the risk: hazard identification, dose–response analysis, exposure assessment, and risk characterization (National Research Council 1983).

Hazard identification

Hazard identification is the process of determining whether exposure to an agent can increase the incidence of a particular health condition. Aflatoxin exposure is associated with an increase in incidence of HCC in humans and sensitive animal species (Groopman et al. 2008); in fact, IARC has classified AFB1 naturally occurring mixes of aflatoxins as a Group 1 carcinogen (IARC 2002).

Dose–response analysis

This second risk assessment step involves characterizing the relationship between the dose of an agent—in this case, aflatoxin—and incidence of HCC. Because of the synergistic impact of aflatoxin and HBV in inducing HCC, the assessment must be done separately for populations with and without chronic HBV infection. Although chronic HCV infection may also have synergistic effects with aflatoxin in inducing HCC, we did not include this effect in the analyses for three reasons: a) there is much less overlap worldwide between aflatoxin and HCV exposures in general; b) chronic HCV infection usually occurs later in life, whereas chronic HBV infection occurs much earlier, thus the time of overlapped exposure is less significant for aflatoxin and HCV (Groopman J, personal communication); and c) much less is known about the quantitative relationship of aflatoxin and HCV in inducing HCC.

For cancer risk assessment, it is traditionally assumed that there is no threshold of exposure to a carcinogen below which there is no observable adverse effect (National Research Council 2008). Cancer potency factors are estimated from the slope of the dose–response relationship, which is assumed to be linear, between doses of the carcinogen and cancer incidence in a population. The IPSC/WHO aflatoxin risk assessment selected two different cancer potency factors for aflatoxin: 0.01 cases/100,000/year/nanogram/kilogram body weight per day aflatoxin exposure for individuals without chronic HBV infection, and 0.30 corresponding cases for individuals with chronic HBV infection. This was based on one cohort study that estimated cancer potency in individuals positive for the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg; a biomarker of chronic HBV infection) and in HBsAg-negative individuals (Yeh et al. 1989), as well as other human studies that assessed cancer potency among either HBsAg-positive or HBsAg-negative individuals. We used these same potency factors for this risk assessment. Because only one of the studies (Yeh et al. 1989) specifically assessed cancer potency in both cohorts, considerable uncertainty may be associated with these potency factors. However, several epidemiological studies confirm that aflatoxin’s cancer potency is about 30 times greater among HBV-positive than among HBV-negative individuals (Kirk et al. 2005, Ok et al. 2007; Qian et al. 1994).

Exposure assessment

Exposure assessment involves estimating the intensity, frequency, and duration of human exposures to a toxic agent. Specifically, we sought to determine how individuals’ exposure to aflatoxin increases their risk of HCC. Aflatoxin exposure is a function not only of aflatoxin concentrations in maize and nuts but also of how much of these foodstuffs individuals consume in different parts of the world.

Aflatoxin exposure assessment has evolved significantly over the past two decades, largely due to the characterization of biomarkers for both aflatoxin exposure and effect (Groopman et al. 2005, 2008). Before these biomarkers, the primary way to estimate aflatoxin exposure was to observe how much maize and nuts people consumed on average and to measure or assume aflatoxin levels in these foods. By measuring biomarkers such as aflatoxin–albumin adducts in serum or aflatoxin-N7-guanine in urine, it is possible to improve estimations of aflatoxin exposure and how much has been biotransformed to increase cancer risk (Groopman et al. 2008).

Because aflatoxin biomarker data worldwide are limited, we collected data on estimated HBV prevalence in these countries and on maize and nut consumption patterns in different world regions and estimated average aflatoxin exposure or contamination levels in the maize and nuts in different world regions. Where aflatoxin exposure data were not already estimated, we used food consumption patterns and aflatoxin contamination levels to estimate exposure. The studies estimating HBV prevalence were based on HBsAg detection among males and among females in both urban and rural settings across all age groups. Data on maize and peanut consumption in different world regions are adapted from the WHO Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS)/Food Consumption Cluster Diets database (WHO 2006). We estimated aflatoxin exposure data in different nations from multiple sources through literature searches.

Risk characterization

This final step of risk assessment integrates dose–response and exposure data to describe the overall nature and magnitude of risk. For our study, this final step consisted of quantifying, across the globe, the burden of aflatoxin-related liver cancer. For each nation, we estimated total number of individuals with or without chronic HBV by multiplying prevalence by population size. To estimate aflatoxin-induced HCC rates within these two populations (with and without chronic HBV infection), we multiplied the corresponding cancer potency factor by aflatoxin exposure estimates. Then we multiplied these values by each nation’s HBV-positive and HBV-negative population sizes to derive total number of aflatoxin-induced HCC cases in each nation. We summed across all world regions to arrive at an estimate for global burden of aflatoxin-induced HCC.

Results

Table 1 lists the prevalence of chronic HBV infection by world region, as measured by HBsAg in different parts of the world. Although these different estimates involve uncertainty and variability, all data are from literature published in or after 2000, to ensure that the HBV prevalence estimates are as current and as relevant as possible. Countries are grouped by WHO designated regions (WHO 2005): Africa, North America and Latin America, Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, Western Pacific, and Europe. Some regions were divided into subgroups because of significantly varied aflatoxin exposure and HBV prevalence within the region.

Table 1.

Estimates of HBV prevalence in select countries based on HBsAg seroprevalence.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Table 2 provides calculations of maize and peanut consumption in select countries of the world. The GEMS/Food Consumption Cluster Diets database divides countries of the world into 13 groups based on diets. For each group cluster, the GEMS food consumption database has estimated the amount of cereals, nuts, and oilseeds consumed. We thus estimated average maize and nut consumption by individual country. There are limitations to these data because of the clustering into 13 groups (with potentially wide ranges among nations within a group), as well as variability in data quality regarding diet and aflatoxin exposure estimates.

Table 2.

Maize and peanut consumption in select countries.

| WHO region/country | Maizea (g/person/day) | Peanutb (g/person/day) |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | ||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 57 | 52 |

| Ethiopia | 83 | 13 |

| The Gambia | 57 | 52 |

| Kenya | 248 | 11 |

| Mozambique | 248 | 11 |

| Nigeria | 57 | 52 |

| South Africa | 248 | 11 |

| Tanzania | 248 | 11 |

| Zimbabwe | 248 | 11 |

| North America and Latin America | ||

| Canada | 86 | 17 |

| United States | 86 | 17 |

| Argentina | 86 | 17 |

| Brazil | 63 | 2 |

| Mexico | 300 | 5 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | ||

| Egypt | 136 | 5 |

| Iran | 32 | 2 |

| Pakistan | 35 | 18 |

| Sudan | 57 | 52 |

| Southeast Asia | ||

| India | 35 | 18 |

| Indonesia | 35 | 18 |

| Thailand | 35 | 18 |

| Western Pacific | ||

| Australia | 86 | 17 |

| China | 35 | 18 |

| Malaysia | 35 | 18 |

| Philippines | 59 | 2 |

| Republic of Korea | 59 | 2 |

| Europe | ||

| Eastern Europe | 32 | 2–10 |

| Southern Europe | 148 | 7 |

| Western Europe | 33 | 10 |

Data are adapted from GEMS/Food Consumption Cluster Diets database (WHO 2006).

Including maize, flour and germ.

Including groundnuts in shell and shelled.

We estimated (based on Tables 1 and 2) or found in the literature the average aflatoxin exposure in different world regions and then calculated the estimated incidence of aflatoxin-induced HCC, with and without the synergistic impact with HBV, in the corresponding populations of each nation and world region (Table 3). Within each WHO-designated region, we found aflatoxin exposures in the most populous nations. The “in general” rows in Table 3 represent a small proportion of each region: nations in which aflatoxin data were not available, or very small nations. For these, we assumed a range for aflatoxin exposure that incorporated the ranges of the nations within the region for which we found aflatoxin data.

Table 3.

Estimated HCC incidence attributable to aflatoxin, by WHO region.

| WHO region/country | Reference | Aflatoxin exposure (ng/kg body weight/daya) | Estimated annual HCC (per 100,000) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg-negative | HBsAg-positive | |||

| Africa | ||||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Manjula et al. 2009b | 0.07–27 | 0.0007–0.27 | 0.02–8.10 |

| Ethiopia | Ayalew et al. 2006b | 1.4–36 | 0.01–0.36 | 0.42–10.8 |

| The Gambia | Hall and Wild 1994; Shephard 2008 | 4–115 | 0.04–1.15 | 1.20–34.5 |

| Kenya | Hall and Wild 1994; Shephard 2008 | 3.5–133 | 0.04–1.33 | 1.05–39.9 |

| Mozambique | Hall and Wild 1994 | 39–180 | 0.39–1.80 | 11.7–54.0 |

| Nigeria | Bandyopadhyay et al. 2007; Bankole and Mabekoje 2004b | 139–227 | 1.39–2.27 | 41.7–68.1 |

| South Africa | Hall and Wild 1994; Shephard 2003 | 0–17 | 0–0.17 | 0–5.10 |

| Tanzania | Manjula et al. 2009b | 0.02–50 | 0.0002–0.50 | 0.06–15.0 |

| Zimbabwe | IPCS/WHO 1998 | 17.5–42.5 | 0.18–0.43 | 5.25–12.8 |

| In generalc | Hall and Wild 1994; Shephard 2008 | 10–180 | 0.10–1.80 | 3.0–54.0 |

| North America | ||||

| Canada | Kuiper-Goodman 1995 | 0.2–0.4d | 0.002–0.004 | 0.06–0.12 |

| United States | IPCS/WHO 1998 | 0.26 | 0.003 | 0.08 |

| In generalc | 0.26–1 | 0.003–0.01 | 0.08–0.3 | |

| Latin America | ||||

| Argentina | Etcheverry et al. 1999; Solovey et al. 1999b | 0–4 | 0–0.04 | 0–1.20 |

| Brazil | IARC 2002; Midio et al. 2001; Oliveira et al. 2009; Vargas et al. 2001b | 0.23–50 | 0.002–0.50 | 0.07–15.0 |

| Mexico | García and Heredia 2006; Guzmán-de-Peña and Peña-Cabriales 2005; Torres et al. 1995b | 14–85 | 0.14–0.85 | 4.20–25.5 |

| In generalc | 20–50 | 0.20–0.50 | 6.0–15.0 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | ||||

| Egypt | Anwar et al. 2008b | 7–57 | 0.07–0.57 | 2.1–17.1 |

| Iran | Hadiani et al. 2009; Mazaheri 2009b | 5–8.5 | 0.05–0.09 | 1.50–2.55 |

| Pakistan | Munir et al. 1989b | 7–50 | 0.07–0.50 | 2.10–15.0 |

| Sudan | Omer et al. 1998 | 19–186 | 0.19–1.86 | 5.70–55.8 |

| In generalc | 10–80 | 0.10–0.80 | 3.00–24.0 | |

| Southeast Asia | ||||

| India | Vasanthi 1998 | 4–100 | 0.04–1.00 | 1.20–30.0 |

| Indonesia | Ali et al. 1998; IARC 2002; Noviandi et al. 2001b | 9–122 | 0.09–1.22 | 2.7–36.6 |

| Thailand | Hall and Wild 1994; Lipigorngoson et al. 2003b | 53–73 | 0.53–0.73 | 15.9–21.9 |

| In generalc | 30–100 | 0.30–1.00 | 9.00–30.0 | |

| Western Pacific | ||||

| Australia | NHMRC 1992; Pitt and Tomaska 2001 | 0.15–0.18 | ~0.002 | ~0.05 |

| China | Li et al. 2001; Qian et al. 1994; Wang and Liu 2007; Wang et al. 2001b | 17–37 | 0.17–0.37 | 5.10–11.1 |

| Malaysia | Ali et al. 1999; IARC 2002b | 15–140 | 0.15–1.4 | 4.5–42 |

| Philippines | Ali et al. 1999; IARC 2002; Sales and Yoshizawa 2005b | 44–54 | 0.44–0.54 | 13.2–16.2 |

| Republic of Korea | Ok et al. 2007; Park et al. 2004 | 1.2–6 | 0.01–0.06 | 0.36–1.80 |

| In generalc | 15–50 (except Australia and New Zealand) | 0.15–0.50 | 4.5–15.0 | |

| Europe | ||||

| Eastern Europe | Malir et al. 2006e | 3.5–4 | 0.04 | ~1.20 |

| Southern Europe | Battilani et al. 2008; Giray et al. 2007f | 0–4 | 0–0.04 | 0–1.20 |

| Western Europe | IARC 2002 | 0.3–1.3 | 0.003–0.01 | 0.09–0.39 |

| In generalc | 0–4 | 0–0.04 | 0–1.2 | |

NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council.

Assuming 60 kg body weight per individual.

Aflatoxin exposure was estimated by multiplying aflatoxin concentrations in staple foods by consumption rates of those foods (WHO 2006).

Aflatoxin exposure estimates and consequent HCC cases for all other countries classified in the same WHO region.

Aflatoxin exposure of 1–2 ng/kg body weight/day was measured in children’s diets; here we assume the adult daily aflatoxin intake is 20% that of children.

Average daily aflatoxin intake was estimated based on AFB1 contamination levels in Czech maize, multiplied by average daily maize consumption in Eastern Europe. fAverage daily aflatoxin intake was estimated based on AFB1 contamination levels in maize of North Italy and Turkey, multiplied by average daily maize consumption in Southern Europe.

These data provide the necessary information to calculate the total estimated cases of aflatoxin-induced HCC cases annually, worldwide. Table 4 lists populations for each relevant nation and world region. Accounting for chronic HBV infection prevalence as shown in Table 1, and the risk estimates for HBV-positive versus HBV-negative individuals in Table 3, the numbers of cases of aflatoxin-induced HCC can be estimated in each world region. These are then summed to produce a global estimate of the number of annual aflatoxin-induced HCC cases. Our estimate is that anywhere from 25,200 to 155,000 annual HCC cases worldwide may be attributable to aflatoxin exposure.

Table 4.

Estimated annual global burden of HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin exposure in HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative populations.

| Annual HCC cases |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO region/country | Population (millions)a | HBsAg-negative | HBsAg-positive |

| Africa | |||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 68 | 1–173 | 1–551 |

| Ethiopia | 85 | 11–288 | 21–643 |

| The Gambia | 1.7 | 1–17 | 3–117 |

| Kenya | 38 | 11–450 | 44–2,270 |

| Mozambique | 21 | 73–361 | 111–1,200 |

| Nigeria | 149 | 1,800–2,940 | 8,200–13,400 |

| South Africa | 48 | 0–79 | 0–255 |

| Tanzania | 41 | 1–195 | 1–554 |

| Zimbabwe | 13 | 19–50 | 68–249 |

| Total region | 755 | 2,150–9,300 | 9,230–50,600 |

| North America | |||

| Canada | 33 | 1 | 1 |

| United States | 300 | 8 | 1–5 |

| Total region | 333 | 9 | 2–5 |

| Latin America | |||

| Argentina | 40 | 0–16 | 0–5 |

| Brazil | 190 | 4–930 | 3–969 |

| Mexico | 109 | 152–924 | 14–83 |

| Total region | 562 | 589–2,980 | 84–2,060 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | |||

| Egypt | 81 | 51–452 | 37–1400 |

| Iran | 66 | 33–56 | 4–9 |

| Pakistan | 172 | 116–832 | 119–851 |

| Sudan | 41 | 58–717 | 140–5,950 |

| Total region | 569 | 446–3,720 | 341–13,200 |

| Southeast Asia | |||

| India | 1,150 | 438–11,200 | 331–16,200 |

| Indonesia | 237 | 203–2,820 | 160–4,340 |

| Thailand | 63 | 307–439 | 461–1,100 |

| Total region | ~1,734 | 1,740–17,300 | 1,460–27,600 |

| Western Pacific region | |||

| Australia | 21 | 0–1 | 0–1 |

| China | 1,300 | 1,990–4,430 | 5,300–14,400 |

| Korea | 50 | 5–29 | 6–45 |

| Malaysia | 28 | 40–372 | 63–588 |

| Philippines | 90 | 333–462 | 594–2,330 |

| Total region | ~1,740 | 2,710–6,510 | 6,310–21,200 |

| Europe | |||

| Eastern Europe | 290 | 94–114 | 61–244 |

| Southern Europe | 144 | 0–56 | 0–121 |

| Western Europe | 183 | 5–24 | 1–7 |

| Total region | 617 | 99–184 | 62–372 |

| Total (world) | 6,280 | 7,700–40,000 | 17,500–115,000 |

| Total annual HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin worldwide | 25,200–155,000 | ||

Data from Central Intelligence Agency 2009.

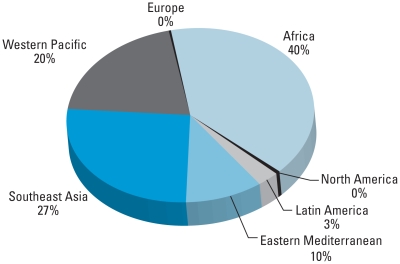

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin globally. The categories denote WHO world regions. Sub-Saharan Africa is the most important region for HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin; Southeast Asia and China (in the Western Pacific region) are also key regions where aflatoxin-related HCC is an important risk. Relatively fewer cases occur in the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, and Europe. Although Australia and New Zealand are grouped with the Western Pacific region, these nations also have low aflatoxin-induced HCC incidence. It is notable that in Mexico, where HBV prevalence is relatively low but aflatoxin contamination in food is relatively high, aflatoxin appears to be a significant risk factor for HCC among those without HBV (an estimated 152–924 HCC cases per year per 100,000 people).

Figure 1.

Distribution of HCC cases attributable to aflatoxin in different regions of the world.

Discussion

Aflatoxin contamination in food is a serious global health problem, particularly in developing countries. Although it has been known for several decades that aflatoxin causes liver cancer in humans, the exact burden of aflatoxin-related HCC worldwide was unknown. This study represents a first step in attempting to estimate that burden. We find that at its lower estimate, aflatoxin plays a role in about 4.6% of total annual HCC cases; at its upper estimate, aflatoxin may play a role roughly 28.2% of all HCC cases worldwide. This large range stems from the considerable uncertainty and variability in data on cancer potency factors, HBV prevalence, aflatoxin exposure, and other risk factors in different world regions. The most heavily afflicted parts of the world are sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and China.

As indicated in Table 3, populations in developing countries in tropical and subtropical areas are nearly ubiquitously exposed to moderate to high levels of aflatoxin. Aflatoxin is a controllable risk factor in food, yet the parts of the world in which the risk is particularly high have limited resources to implement most aflatoxin control strategies. Much agricultural land in Africa and Asia lies in climatic regions favorable for A. flavus and A. parasiticus proliferation. Suboptimal field practices and poor drying/storage conditions make crops vulnerable to fungal infection and aflatoxin accumulation. Maize and groundnuts, the two crops most conducive to Aspergillus infection, are staples in many African and Asian diets. Because the very poor in these regions cannot afford much food variety, these staples make up a significant portion of their diets, increasing aflatoxin exposure.

Even within the same nation, aflatoxin-induced HCC risk can vary significantly among different populations, hence the large national ranges for risk shown in Table 4. Rural populations generally have higher levels of aflatoxin exposure than do urban dwellers in developing countries (Wild and Hall 2000), because urban populations typically consume more diversified diets than do rural dwellers and may have food that is better controlled for contaminants. In addition, there is a strong seasonal variation in aflatoxin exposure that correlates with food availability (Gnonlonfin et al. 2008; Tajkarimi et al. 2007). Moreover, HBV prevalence is generally higher in rural areas than in urban ones, and higher among males than among females in most places (Plymoth et al. 2009). We present our collected data of HBsAg seroprevalence as a range for countries or populations (Table 1), to account for these variations.

Although many nations that suffer from both high aflatoxin exposures and high HBV prevalence have nominally established maximum allowable aflatoxin standards in food, there is little if any enforcement of these standards in many rural areas. Indeed, the food in subsistence farming and local food markets is rarely formally inspected. Strict aflatoxin standards can even lead to large economic losses for poor food-exporting nations when trading with other nations (Wu 2004). Subsistence farmers and local food traders sometimes have the luxury of discarding obviously moldy maize and groundnuts. But in drought seasons, oftentimes people have no choice but to eat moldy food or starve (Williams 2008).

Multiple public health interventions exist to control the burden of aflatoxin in the body and to prevent HCC. These interventions, described in greater detail in Wu and Khlangwiset (2010), can be grouped into three categories: agricultural, dietary, and clinical. Agricultural interventions can be applied either in the field (preharvest) or in storage and transportation (postharvest) to reduce aflatoxin levels in key crops. They can thus be considered primary interventions. Dietary and clinical interventions can be considered secondary interventions. They cannot reduce actual aflatoxin levels in food, but they can reduce aflatoxin-related illness, either by reducing aflatoxin’s bioavailability in the body or by ameliorating aflatoxin-induced damage. Because aflatoxin-mediated mutations may precede HCC by several years, the effects of reducing aflatoxin exposure on HCC incidence may take time to become apparent (Szymañska et al. 2009).

One highly effective clinical intervention to reduce aflatoxin-related HCC is vaccination against HBV. Vaccinating children against HBV has, over the past 30 years, significantly decreased HBV infection in several regions, including Europe (Bonanni et al. 2003; Williams et al. 1996), Taiwan (Chen et al. 1996), and Thailand (Jutavijittum et al. 2005). This vaccine will, over time, lessen the global carcinogenic impact of aflatoxin, because removing the synergistic impact between HBV and aflatoxin exposure would significantly reduce HCC risk. However, there are currently roughly 360 million chronic HBV carriers worldwide, and HBV vaccination is still not incorporated into many national immunization programs (Wild and Hall 2000). Thus, adopting measures to reduce dietary exposure to aflatoxins is crucial for public health.

Our study highlights the significant role of aflatoxin in contributing to global liver cancer burden. Most cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and China, where populations suffer from both high HBV prevalence and largely uncontrolled exposure to aflatoxin in the food. Not all risk factors for HCC, including synergistic roles between aflatoxin and other carcinogens, are clearly understood; hence, these estimates for number of global aflatoxin-induced HCC cases have a large range. Although it is impossible to completely eliminate aflatoxin in food worldwide, it is possible to significantly reduce levels and dramatically reduce liver cancer incidence worldwide. The challenge remains to deliver these interventions to places of the world where they are most needed.

Footnotes

We thank T. Kensler (University of Pittsburgh), J. Groopman (Johns Hopkins University), and C. Wild (International Agency for Research on Cancer) for their helpful comments.

This work was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (KL2 RR024153).

The authors’ salaries are supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

References

- Abebe A, Nokes DJ, Dejene A, Enquselassie F, Messele T, Cutts FT. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: transmission patterns and vaccine control. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131(1):757–770. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803008574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou M, Eltahir Y, Ali A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among blood donors in Nyala, South Dar Fur, Sudan. Virol J. 2009;6:146. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M, Zaidi S, Malik S, Naeem A, Shaukat S, Sharif S, et al. Serology based disease status of Pakistani population infected with Hepatitis B virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-64. [Online 27 June 2007] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N, Hashim NH, Yoshizawa T. Evaluation and application of a simple and rapid method for the analysis of aflatoxins in commercial foods from Malaysia and the Philippines. Food Addit Contam Part A. 1999;16(7):273–280. doi: 10.1080/026520399283939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N, Sardjono, Yamashita A, Yoshizawa T. Natural co-occurrence of aflatoxins and Fusavium mycotoxins (fumonisins, deoxynivalenol, nivalenol and zearalenone) in corn from Indonesia. Food Addit Contam Part A. 1998;15(4):377–384. doi: 10.1080/02652039809374655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SA, Donahue RMJ, Qureshi H, Vermund SH. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Pakistan: prevalence and risk factors. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen R, Sanad N, Al-Shemmari S, Siddique I, Chowdhury RI, Al-Hamdan S, et al. Prevalence of viral markers among first-time Arab blood donors in Kuwait. Transfusion. 2005;45(12):1973–1980. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar WA, Khaled HM, Amra HA, El-Nezami H, Loffredo CA. Changing pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and its risk factors in Egypt: possibilities for prevention. Mutat Res. 2008;659(1–2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew A, Fehrmann H, Lepschy J, Beck R, Abate D. Natural occurrence of mycotoxins in staple cereals from Ethiopia. Mycopathologia. 2006;162(1):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11046-006-0027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay R, Kumar M, Leslie JF. Relative severity of aflatoxin contamination of cereal crops in West Africa. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2007;24(10):1109–1114. doi: 10.1080/02652030701553251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole SA, Mabekoje OO. Occurrence of aflatoxins and fumonisins in preharvest maize from south-western Nigeria. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2004;21(3):251–255. doi: 10.1080/02652030310001639558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batayneh N, Bdour S. Risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus in Jordan. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2002;10(3):127–132. doi: 10.1155/S1064744902000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batina A, Kabemba S, Malengela R. Infectious markers among blood donors in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Rev Med Brux. 2007;28(3):145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battilani P, Barbano C, Piva G. Aflatoxin B1 contamination in maize related to the aridity index in North Italy. World Mycotox J. 2008;1(4):449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Behal R, Jain R, Behal KK, Bhagoliwal A, Aggarwal N, Dhole TN. Seroprevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection among general population in Northern India. Arq Gastroenterol. 2008;45(2):137–140. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032008000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanni P, Pesavento G, Bechini A, Tiscione E, Mannelli F, Benucci C, et al. Impact of universal vaccination programmes on the epidemiology of hepatitis B: 10 years of experience in Italy. Vaccine. 2003;21(7–8):685–691. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00580-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt T, Amin M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among young adult males in Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(4):791–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease Burden from Viral Hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. 2009. [[accessed 5 November 2009]]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics.htm#section1.

- Central Intelligence Agency. World Factbook. 2009. [[accessed 18 August 2009]]. Available: https:// www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

- Chen H, Chang MH, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Lee PI, Lee CY, et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in children: ten years of mass vaccination in Taiwan. JAMA. 1996;276(11):906–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C, Evans AA, London WT, Block J, Conti M, Block T. Underestimation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States of America. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15(1):12–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha L, Plouzeau C, Ingrand P, Gudo JPS, Ingrand I, Mondlane J, et al. Use of replacement blood donors to study the epidemiology of major blood-borne viruses in the general population of Maputo, Mozambique. J Med Virol. 2007;79(12):1832–1840. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custer B, Sullivan SD, Hazlet TK, Iloeje U, Veenstra DL, Kowdley KV. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus. J Clin Gastroentorol. 2004;38(10 suppl 3):S158–S168. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200411003-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Villa G, Piccinino, Scolastico C, Fusco M, Piccinino R, Sepe A. Long-term epidemiological survey of hepatitis B virus infection in a hyperendemic area (Afragola, southern Italy): results of a pilot vaccination project. Res Virol. 1998;149(5):263–270. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2516(99)89004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E. Chronic hepatitis B in the Philippines: problems posed by the hepatitis B surface antigen-positive carrier. In: Zuckerman A, editor. Hepatitis B in the Asian-Pacific Region, vol. 1— Screening, Diagnosis and Control. London: Royal College of Physicians; 1997. pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheikh R, Daak A, Elsheikh M, Karsany M, Adam I. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in pregnant Sudanese women. Virol J. 2007;4:104. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-104. [Online 24 October 2007] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry M, Nesci A, Barros G, Torres A, Chulze S. Occurrence of Aspergillus section Flavi and aflatoxin B1 in corn genotypes and corn meal in Argentina. Mycopathologia. 1999;147(1):37–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1007040123181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola F, Kotila T, Akinyemi J. Trends in transfusion-transmitted viral infections from 2001 to 2006 in Ibadan, Nigeria. Intervirology. 2008;51(6):427–431. doi: 10.1159/000209671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2002: Cancer Incidence. Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. 2004. [[accessed 27 April 2010]]. IARC CancerBase No. 5, version 2.0. Available: http://www-dep.iarc.fr. Available: http://www-dep.iarc.fr/globocan/downloads.htm.

- García S, Heredia N. Mycotoxins in Mexico: epidemiology, management, and control strategies. Mycopathologia. 2006;162(3):255–264. doi: 10.1007/s11046-006-0058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giray B, Girgin G, Engin AB, AydIn S, Sahin G. Aflatoxin levels in wheat samples consumed in some regions of Turkey. Food Control. 2007;18(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.08.002. [Online 29 September 2005] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnonlonfin GJ, Hell K, Fandohan P, Siame AB. Mycoflora and natural occurrence of aflatoxins and fumonisin B1 in cassava and yam chips from Benin, West Africa. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;122(1–2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogos CA, Fouka KP, Nikiforidis G, Avgeridis K, Sakellaropoulos G, Bassaris H, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection in the general population and selected groups in South-Western Greece. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(6):551–557. doi: 10.1023/a:1024698715741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman JD, Johnson D, Kensler TW. Aflatoxin and hepatitis B virus biomarkers: a paradigm for complex environmental exposures and cancer risk. Cancer Biomark. 2005;1(1):5–14. doi: 10.3233/cbm-2005-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groopman JD, Kensler TW, Wild CP. Protective interventions to prevent aflatoxin-induced carcinogenesis in developing countries. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:187–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust ID. Epidemiology of hepatitis B infection in the Western Pacific and South East Asia. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S18–S23. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-de-Peña D, Peña-Cabriales JJ. Regulatory considerations of aflatoxin contamination of food in Mexico. Rev Latinoam Microbiol. 2005;47(3–4):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadiani M, Yazdanpanah H, Amirahmadi M, Soleimani H, Shoeibi S, Khosrokhavar R. Evaluation of aflatoxin contamination in maize from Mazandaran province in Iran. J Med Plants. 2009;8(suppl 5):109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hahné S, Ramsay M, Balogun K, Edmunds WJ, Mortimer P. Incidence and routes of transmission of hepatitis B virus in England and Wales, 1995–2000: implications for immunisation policy. J Clin Virol. 2004;29(4):211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AJ, Wild CP. Epidemiology of aflatoxin-related disease. In: Eaton DA, Groopman JD, editors. The Toxicology of Aflatoxins: Human Health, Veterinary and Agricultural Significance. San Diego, CA: Academia Press; 1994. pp. 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa I, Tanaka Y, Kurbanov F, Yoshihara N, El-Gohary A, Lyamuya E, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in the United Republic of Tanzania. J Med Virol. 2006;78(8):1035–1042. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SH, Bosch FX, Troxell TC, Bolger PM. Policy forum: public health. Reducing liver cancer—global control of aflatoxin. Science. 1999;286(5449):2453–2454. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Zou S, Giulivi A. Hepatitis B and its control in Southeast Asia and China. [[accessed 19 May 2010]];Can Commun Dis Rep. 2001 27(suppl 3):31–33. Available: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/01vol27/27s3/27s3k_e.html. [Google Scholar]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) Some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2002;82:171–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Programme on Chemical Safety and WHO. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Safety evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. 1998. [[accessed 19 May 2010]]. WHO Food Additives Series 40. Available: http://www.inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v040je01.htm.

- Ismail AM, Ziada HN, Sheashaa HA, Shehab El-Din AB. Decline of viral hepatitis prevalence among asymptomatic Egyptian blood donors: a glimmer of hope. Eur J Int Med. 2009;20(5):490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafri W, Jafri N, Yakoob J, Islam M, Tirmizi SFA, Jafar T, et al. Hepatitis B and C: prevalence and risk factors associated with seropositivity among children in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-101. [online 23 June 2006] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilg W, Hottenträger B, Weinberger K, Schlottmann K, Frick E, Holstege A, et al. Prevalence of markers of hepatitis B in the adult German population. J Med Virol. 2001;63(2):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutavijittum P, Jiviriyawat Y, Yousukh A, Hayashi S, Toriyama K. Evaluation of a hepatitis B vaccination program in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(1):207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafi-Abad SA, Rezvan H, Abolghasemi H. Trends in prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among Iranian blood donors, 1998–2007. Transfus Med. 2009a;19(4):189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafi-Abad SA, Rezvan H, Abolghasemi H, Talebian A. Prevalence and trends of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among blood donors in Iran, 2004 through 2007. Transfusion. 2009b;49(10):2214–2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khattak M, Salamat N, Bhatti FA, Qureshi TZ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in blood donors in northern Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(9):398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiire CF. The epidemiology and prophylaxis of hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: a view from tropical and subtropical Africa. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S5–S12. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk GD, Bah E, Montesano R. Molecular epidemiology of human liver cancer: insights into etiology, pathogenesis and prevention from The Gambia, West Africa. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(10):2070–2082. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk GD, Lesi OA, Mendy M, Akano AO, Sam O, Goedert JJ, et al. The Gambia Liver Cancer Study: infection with hepatitis B and C and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in West Africa. Hepatology. 2004;39(1):211–219. doi: 10.1002/hep.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk GD, Lesi OA, Mendy M, Szymanska K, Whittle H, Goedert JJ, et al. 249(ser) TP53 mutation in plasma DNA, hepatitis B viral infection, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24(38):5858–5867. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S-Y, Lekawanvijit S, Maneekarn N, Thongsawat S, Brodovicz K, Nelson K, et al. Hepatitis B 1762T/1764A mutations, hepatitis C infection, and codon 249 p53 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas from Thailand. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(2):380–384. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper-Goodman T. Mycotoxins: risk assessment and legislation. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82–83:853–859. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansang M. Epidemiology and control of hepatitis B infection: perspective from the Philippines, Asia. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S43–S47. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman EM, Wilson ML. Epidemiology of hepatitis viruses among hepatocellular carcinoma cases and healthy people in Egypt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(3):690–697. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FQ, Yoshizawa T, Kawamura O, Luo XY, Li YW. Aflatoxins and fumonisins in corn from the high-incidence area for human hepatocellular carcinoma in Guangxi, China. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49(8):4122–4126. doi: 10.1021/jf010143k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipigorngoson S, Limtrakul P, Suttajit M, Yoshizawa T. In-house direct cELISA for determining aflatoxin B 1 in Thai corn and peanuts. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2003;20(9):838–845. doi: 10.1080/0265203031000156060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdzik W. Hepatitis B epidemiology in Poland, Central and Eastern Europe and the newly independent states. Vaccine. 2000;18(suppl 1):S13–S16. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malir F, Ostry V, Grosse Y, Roubal T, Skarkova J, Ruprich J. Monitoring the mycotoxins in food and their biomarkers in the Czech Republic. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50(6):513–518. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjula K, Hell K, Fandohan P, Abass A, Bandyopadhyay R. Aflatoxin and fumonisin contamination of cassava products and maize grain from markets in Tanzania and republic of the Congo. Toxin Rev. 2009;28:63. doi: 10.1080/15569540802462214. [Online 2 May 2009] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matee M, Magesa P, Lyamuya E. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis infections among blood donors at the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-21. [online 30 January 2006] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaheri M. Determination of aflatoxins in imported rice to Iran. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47(8):2064–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbendi Nlombi C, Longo-Mbenza B, Mbendi Nsukini S, Muyembe Tamfum JJ, Situakibanza Nanituma H, Vangu Ngoma D. Prevalence of HIV and HBs antigen in blood donors. Residual risk of contamination in blood recipients in East Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Med Trop (Mars) 2001;61(2):139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merican I, Guan R, Amarapuka D, Alexander MJ, Chutaputti A, Chien RN, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Asian countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(12):1356–1361. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.0150121356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midio AF, Campos RR, Sabino M. Occurrence of aflatoxins B1, B2, G1 and G2 in cooked food components of whole meals marketed in fast food outlets of the city of Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil. Food Addit Contam PART A. 2001;18(5):445–448. doi: 10.1080/02652030120070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Shao JF, Weaver DJ, Shimokura GH, Paul DA, Lallinger GJ. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis in Tanzanian adults. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3(9):757–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuk GY, Uhanova J. Chronic hepatitis B infection in Canada. Can J Infect Dis. 2001;12(6):351–356. doi: 10.1155/2001/650313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munir M, Saleem M, Malik ZR, Ahmed M, Ali A. Incidence of aflatoxin contamination in non-perishable food commodities. J Pak Med Assoc. 1989;39(6):154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata S, Song P, Duc DD, Nguyen XQ, Murata K, Tsuda F, et al. Hepatitis C and B virus infections in populations at low or high risk in Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi, Vietnam. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9(4):416–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. The 1990 Australia Market Basket Survey. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Noviandi CT, Razzazi E, Agus A, Böhm J, Hulan HW, Wedhastri S, et al. Natural occurrence of aflatoxin B1 in some Indonesian food and feed products in Yogyakarta in year 1998–1999. Mycotoxin Res. 2001;17(0):174–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03036430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ok HE, Kim HJ, Bo Shim W, Lee H, Bae DH, Chung DH, et al. Natural occurrence of aflatoxin B1 in marketed foods and risk estimates of dietary exposure in Koreans. J Food Protect. 2007;70(12):2824–2828. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.12.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira CA, Gonçalves NB, Rosim RE, Fernandes A. Determination of aflatoxins in peanut products in the northeast region of São Paulo, Brazil. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(1):174–183. doi: 10.3390/ijms10010174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer RE, Bakker MI, van’t Veer P, Hoogenboom RL, Polman TH, Alink GM, et al. Aflatoxin and liver cancer in Sudan. Nutr Cancer. 1998;32(3):174–180. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraná R, Almeida D. HBV epidemiology in Latin America. J Clin Virol. 2005;34(suppl 1):S130–S133. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)80022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JW, Kim EK, Kim YB. Estimation of the daily exposure of Koreans to aflatoxin B1 through food consumption. Food Addit Contam PART A. 2004;21(1):70–75. doi: 10.1080/02652030310001622782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt JI, Tomaska L. Are mycotoxins a health hazard in Australia? Food Austr. 2001;53(12):545–559. [Google Scholar]

- Plymoth A, Viviani S, Hainaut P. Control of hepatocellular carcinoma through Hepatitis B vaccination in areas of high endemicity: perspectives for global liver cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2009;286(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian GS, Ross RK, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Gao YT, Henderson BE. A follow-up study of urinary markers of aflatoxin exposure and liver cancer risk in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resuli B, Prifti S, Kraja B, Nurka T, Basho M, Sadiku E. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Albania. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(7):849–852. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman S, Panduro A, Aguilar-Gutierrez Y, Maldonado M, Vazquez-VanDyck M, Martinez-Lopez E, et al. A low steady HBsAg seroprevalence is associated with a low incidence of HBV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Mexico: a systematic review. Hepatol Int. 2009;3(2):343–355. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9115-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales AC, Yoshizawa T. Updated profile of aflatoxin and Aspergillus section Flavi contamination in rice and its byproducts from the Philippines. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2005;22(5):429–436. doi: 10.1080/02652030500058387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard GS. Aflatoxin and food safety: recent African perspectives. Toxin Rev. 2003;22:267. doi: 10.1081/TXR-120024094. [Online 8 November 2003] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard GS. Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food in Africa. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2008;25(10):1246–1256. doi: 10.1080/02652030802036222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimelis T, Torben W, Medhin G, Tebeje M, Andualm A, Demessie F, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection among people attending the voluntary counselling and testing centre and anti-retroviral therapy clinic of St Paul’s General Specialised Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(1):37–41. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovey MMS, Somoza C, Cano G, Pacin A, Resnik S. A survey of fumonisins, deoxynivalenol, zearalenone and aflatoxins contamination in corn-based food products in Argentina. Food Addit Contam Part A. 1999;16(8):325–329. doi: 10.1080/026520399283894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song E, Yun YM, Park MH, Seo DH. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in a general adult population in Korea. Intervirology. 2009;52(2):57–62. doi: 10.1159/000214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosnider H, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Banziger M, Bhat RV, Breiman R, Brune M, et al. Workgroup report: public health strategies for reducing aflatoxin exposure in developing countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1898–1903. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymañska K, Chen JG, Cui Y, Gong YY, Turner PC, Villar S, et al. TP53 R249S mutations, exposure to aflatoxin, and occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of chronic hepatitis B virus carriers from Qidong, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(5):1638–1643. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajkarimi M, Shojaee Aliabadi F, Salah Nejad M, Pursoltani H, Motallebi AA, Mahdavi H. Seasonal study of aflatoxin M1 contamination in milk in five regions in Iran. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;116(3):346–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon BN, Acharya SK, Tandon A. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in India. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S56–S59. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanprasert S, Somjitta S. Trend study on HBsAg prevalence in Thai voluntary blood donors. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1993;24(suppl 1):43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayou CT, Amadou D, Rakia Y, Marc H, Antoine N, Guy M, et al. Characteristics of blood donors and donated blood in sub-Saharan francophone Africa. Transfusion. 2009;49(8):1592–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JR. Hepatitis B and hepatitis delta virus infection in South America. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S48–S55. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres Espinosa E, Acuña Askar K, Naccha Torres LR, Montoya Olvera R, Castrellón Santa Anna J. Quantification of aflatoxins in corn distributed in the city of Monterrey, Mexico. Food Addit Contam. 1995;12(3):383–386. doi: 10.1080/02652039509374319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tswana S, Chetsanga C, Nyström L, Moyo S, Nzara M, Chieza L. A sero-epidemiological cross-sectional study of hepatitis B virus in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1996;86(1):72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuei J, Okoth F, Kasomo A, Ireri E, Kaptich D, Watahi A, et al. Prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma, liver cirrhosis and HBV carriers in liver disease patients referred to Clinical Research Centre, Kemri. Afr J Health Sci. 1994;1(3):126–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vall Mayans M, Hall AJ, Inskip HM, Chotard J, Lindsay SW, Coromina E, et al. Risk factors for transmission of hepatitis B virus to Gambian children. Lancet. 1990;336(8723):1107–1109. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92580-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hattum J, Boland GJ, Jansen KG, Kleinpenning AS, van Bommel T, van Loon AM, et al. Transmission profile of hepatitis B virus infection in the Batam region, Indonesia. Evidence for a predominantly horizontal transmission profile. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;531:177–183. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0059-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas EA, Preis RA, Castro L, Silva CMG. Co-occurrence of aflatoxins B 1, B 2, G 1, G 2, zearalenone and fumonisin B 1 in Brazilian corn. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2001;18:981. doi: 10.1080/02652030110046190. [Online 11 November 2001] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasanthi S, Bhat RV. Mycotoxins in foods—occurrence, health and economic significance and food control measures. Ind J Med Res. 1998;108:212–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Huang T, Su J, Liang F, Wei Z, Liang Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma and aflatoxin exposure in Zhuqing Village, Fusui County, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(2):143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu XM. Contamination of aflatoxins in different kinds of foods in China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2007;20(6):483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Vaccine Product Selection Menu. A Guide for National Immunization Managers when Introducing GAVI/The Vaccine Fund Supported Vaccines. 2005. [[accessed 27 April 2010]]. Available: http://www.who.int/immunization_delivery/new_vaccines/4.Coreinformation_Hepatitis%20B.pdf.

- WHO. Global Environment Monitoring System—Food Contamination Monitoring and Assessment Programme (GEMS/Food) 2006. [[accessed 20 August 2009]]. Available: http://www.who.int/foodsafety/chem/gems/en/index1.html.

- WHO. Western Pacific Regional Plan for Hepatitis B Control through Immunization. Manila, Philippines: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [[accessed 27 April 2010]]. Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP, Gong YY. Mycotoxins and human disease: a largely ignored global health issue. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:71–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP, Hall AJ. Primary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2000;462(2–3):381–393. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP, Montesano R. A model of interaction: aflatoxins and hepatitis viruses in liver cancer aetiology and prevention. Cancer Lett. 2009;286(1):22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH. Institutional stakeholders in mycotoxin issues—past, present and future. In: Leslie JF, Bandyopadhyay R, Visconti A, editors. Mycotoxins: Detection Methods, Management, Public Health and Agricultural Trade. Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International; 2008. pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Nokes DJ, Medley GF, Anderson RM. The transmission dynamics of hepatitis B in the UK: a mathematical model for evaluating costs and effectiveness of immunization programmes. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:71–89. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. Mycotoxin risk assessment for the purpose of setting international regulatory standards. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38(15):4049–4055. doi: 10.1021/es035353n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Khlangwiset P. Health economic impacts and cost-effectiveness of aflatoxin reduction strategies in Africa: case studies in biocontrol and postharvest interventions. Food Addit Contam: Part A. 2010;27:496. doi: 10.1080/19440040903437865. [Online 4 April 2010] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FS, Yu MC, Mo CC, Luo S, Tong MJ, Henderson BE. Hepatitis B virus, aflatoxins, and hepatocellular carcinoma in southern Guangxi, China. Cancer Res. 1989;49(9):2506–2509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef A, Yano Y, Utsumi T, abd El-alah EM, abd El-Hameed AE, Serwah AH, et al. Molecular epidemiological study of hepatitis viruses in Ismailia, Egypt. Intervirology. 2009;52(3):123–131. doi: 10.1159/000219385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zou S, Giulivi A. Hepatitis B in Canada. [[accessed 27 April 2010]];Can Commun Dis Rep. 2001 27(suppl 3):10–12. Available: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/01vol27/27s3/27s3e_e.html. [Google Scholar]