Abstract

Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) is the predominant form of brain injury and the leading known cause of cerebral palsy and cognitive deficits in premature infants. The number of low-birth-weight infants who survive to demonstrate these neurologic deficts is increasing. Magnetic resonance imaging–based neuroimaging techniques provide greater diagnostic sensitivity for PVL than does head ultrasonography and often document the involvement of telencephalic gray matter and long tracts in addition to periventricular white matter. The neuropathologic hallmarks of PVL are microglial activation and focal and diffuse periventricular depletion of premyelinating oligodendroglia. Premyelinating oligodendroglia are highly vulnerable to death caused by glutamate, free radicals, and proinflammatory cytokines. Studies in animal models of PVL suggest that pharmacologic interventions that target these toxic molecules will be useful in diminishing the severity of PVL.

Ischemic and inflammatory injuries to the developing brain can lead to devastating neurologic consequences. The pattern of perinatal brain injury is highly age-dependent. In term infants, such injuries predominantly affect neurons in the cerebral cortex, yielding watershed or stroke-like distributions of damage, whereas in premature infants, immature oligodendroglia in the cerebral white matter and subplate neurons immediately below the neocortex are especially vulnerable, resulting in periventricular leukomalacia (PVL).1,2

The magnitude of the problem posed by brain injury in the premature infant is extraordinary. Improved neonatal intensive care has led to nearly 90% survival of the approximately 50 000 infants in the United States yearly with birth weight less than 1500 g. Between 5% and 10% of survivors subsequently exhibit substantial motor defects, and 25% to 50% of the remainder exhibit sensory, cognitive, and behavioral deficits. Periventricular leukomalacia is the predominant form of brain injury underlying this neurologic morbidity and is the most common cause of cerebral palsy in premature infants.

BRAIN IMAGING IN PVL

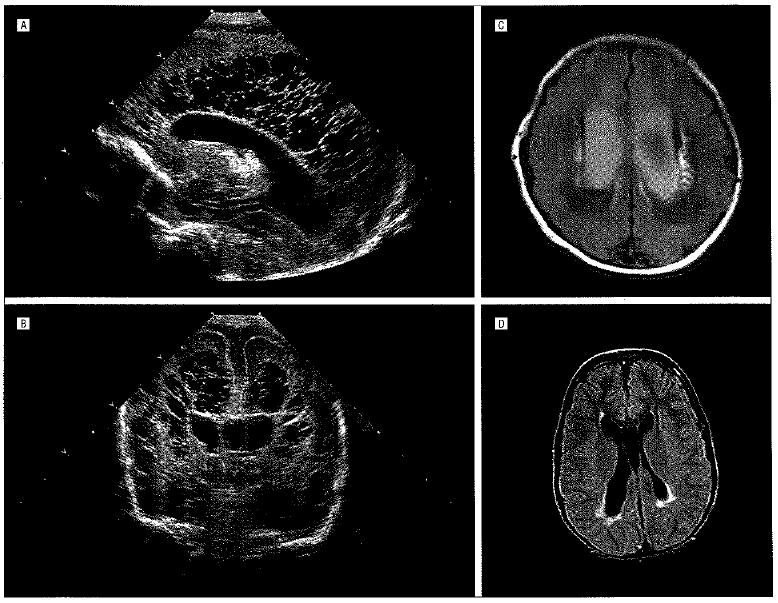

Periventricular leukomalacia is most often diagnosed in the neonatal intensive care unit by means of head ultrasonography, which demonstrates increased periventricular white matter echogenicity with or without cystic abnormalities (Figure 1). Occasionally, PVL is detectable by means of ultrasonography at birth or even in utero; however, cystic abnormalities often do not become visible at ultrasonography until 1 week or longer after birth. Periventricular leukomalacia can be all but excluded with normal findings at postnatal cranial ultrasonographic examinations performed at 1 week and 1 month after birth. In premature infants in whom repeated ultrasonography shows only increased periventricular echogenicity without cysts, less than 5% will subsequently develop overt cerebral palsy, although substantially more will show evidence of cognitive dysfunction. The incidence of cerebral palsy, sometimes complicated by refractory complex partial seizures, is much higher in infants with ultrasonically demonstrable cystic lesions.3

Figure 1.

Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL). Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) cranial untrasonograms obtained at age 2 days. Images exemplify extensive bilateral cystic PVL. This twin born at 29 weeks of gestation had fetal heart rate decelerations and Apgar scores of 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, related to his role as donor in twin-twin transfusion syndrome. C, Magnetic resonance image (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) obtained at age 10 days in an infant born at 34 weeks of gestation. Image shows bilateral enlarged, blood-filled ventricles and prominent bilateral periventricular high-signal areas in the white matter lateral to the ventricles, consistent with PVL. The mother, who had diabetes, had pregnancy-induced hypertension, which was treated with magnesium sulfate. The baby, with Apgar scores of 2 and 2 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, developed status epilepticus that responded to treatment with phenobarbital sodium. Shortly after birth, he developed severe bilateral intraventricular hemorrhages with posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus, a frequent concomitant of PVL. D, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) in a 9-year-old girl with intractable complex seizures since infancy. There are peritrigonal high-signal areas, consistent with PVL. She had been born at 37 weeks of gestation to a mother with diabetes, and developed severe hypoxia. which was treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Magnetic resonance imaging, while not always feasible in unstable premature infants, is often successful in visualizing PVL even earlier in the neonatal period than ultrasonography and, especially with repeated studies and diffusion tensor imaging, can provide prognostic information by documenting gray matter atrophy and tract degenerations.4,5 In such patients, PVL is clearly a disease of both gray matter and white matter.

Premature infants, in particular, those born before 32 weeks of gestation, are vulnerable to germinal matrix hemorrhages, which often occur in conjunction with PVL. Hemorrhages confined to germinal matrix do not have a major effect on prognosis; however, if blood penetrates into the ventricles, cerebrospinal fluid dynamics may be impaired, giving rise to hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus, if severe, can distort the corticospinal tracts and intensify the spastic diplegia that is a frequent consequence of PVL.3,6

PATHOGENESIS OF PVL: OBSERVATIONS IN HUMAN BEINGS

Epidemiologic studies indicate that the incidence of PVL is highly correlated with prematurity and less strongly correlated with chorioamnionitis. Neonatal hypocarbia and hypotension increase the incidence of PVL in premature infants.7,8 Prolonged cardiac surgery is associated with a high incidence of PVL even in term infants.9,10

Continuous near-infrared spectroscopic recording demonstrates frequent episodes of failure of arteriolar autoregulation of cerebral perfusion in sick premature infants; this increases their vulnerability to forebrain ischemia when systemic blood pressure decreases as a result of sepsis or other causes.11 Vulnerability of periventricular white matter to impaired perfusion in premature infants is compounded by the relative sparseness of periventricular vascularity during the third trimester of gestation.12

Most cells of oligodendroglial lineage in the human telencephalon in the third trimester of gestation are premyelinating oligodendroglia; these cells are selectively depleted in the periventricular regions in premature infants with PVL. Microglia are numerous in human telencephalic periventricular and subplate regions in the third trimester of gestation13,14 and become activated in PVL. Toxic products of these activated microglia likely contribute to death of premyelinating oligodendroglia. The failure of reconstitution of the periventricular oligodendroglial lineage from spared germinal matrix progenitors after the acute phase of PVL is as vet unexplained.

Subplate neurons, which lie just below the developing cerebral cortex until removed by a normal process of programmed apoptosis during the third trimester of gestation, have an essential role in the axonal targeting required for formation of mature thalamocortical connections. These neurons, like premyelinating oligodendroglia, are vulnerable to ischemia, and accelerated loss of subplate neurons in PVL may contribute substantially to subsequent motor, visual, and cognitive deficits.2

PREVENTION OF PVL: CURRENT CLINICAL PRACTICE

Careful attention to blood gas values is valuable in diminishing the severity of PVL; prevention of arterial Pco2 levels that fall below 35 mm Hg substantially lowers the risk of cerebral palsy.7,8 In one large study, the incidence of PVL in low-birth-weight infants with respiratory failure was also substantially reduced by inhalation of low concentrations of nitric oxide,15 possibly owing to improved oxygenation resulting from this therapy. Magnesium sulfate administered shortly before delivery of premature infants does not substantially diminish the incidence of cerebral palsy.16 Cooling of the head or whole body may reduce neurologic disability in moderately asphyxiated full-term neonates,17 but has not yet been critically evaluated in premature infants. Clearly, new approaches are needed to diminish PVL and the burden of neurologic disability it causes in premature infants. Attention has turned, therefore, to studies of the pathophysiology and therapy of PVL in experimental animals.

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS OF PVL

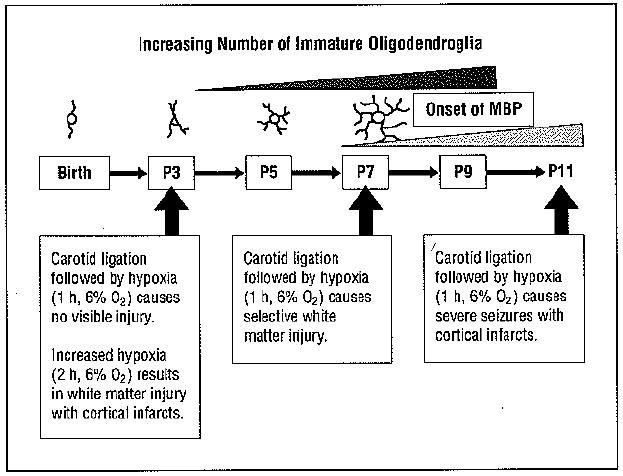

Two methods elicit selective periventricular white matter lesions in the forebrains of immature experimental animals: induction of central nervous system hypoxiaischemia, customarily by combining unilateral carotid occlusion and reduced ambient oxygen (Figure 2), and activation of the innate immune system by administration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Both approaches elicit diffuse microglial activation, overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, and depletion of periventricular premyelinating oligodendroglia.

Figure 2.

Rodent model of periventricuiar leukomalacia. The pattern of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury is both highly age-specific and dependent on the severity of the insult. The complexity of processes elaborated by cells of the oligodendroglial lineage as a function of developmental stage is shown in schematic fashion, ranging from the 1 or 2 processes characteristic of motile oligodendroglial progenitors to the complex process network of premyelinating oligodendroglia. MBP indicates myelin basic protein; P, postnatal day.

Unlike in human beings, in whom mature oligodendroglia begin to appear in forebrain and initiate myelination in the third trimester of gestation, terminal oligodendroglial differentiation and myelination in the mouse and rat begin postnatally. Most neonatal mouse and rat telencephalon oligodendroglial lineage cells are premyelinating oligodendroglia. Like human premyelinating oligodendroglia, these cells have exited the mitotic cycle, elaborated multiple processes, and synthesized galactolipids characteristic of myelin but have not yet translated substantial amounts of structural myelin proteins such as proteolipid and myelin basic protein. Premyelinating oligodendroglia are more susceptible than oligodendroglial progenitors or mature oligodendroglia to glutamate-induced calcium loading and excitotoxic death. This is a consequence of their heightened assembly of edited GluR2-free, calcium-permeable α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate receptors (AMPARs).18 Oligodendroglial progenitors also persist in the third trimester of gestation in human and neonatal rat and mouse telencephalon. These motile, actively mitosing cells, though less susceptible to glutamate toxicity than premyelinating oligodendroglia, are especially vulnerable to the toxic effects of proinflammatory cytokines produced by activated microglia.l9

As in PVL in human beings, experimental PVL involves neurons and glia. Subplate neurons undergo premature apoptosis in neonatal rodents subjected to ischemic injury.20 In addition, whereas routine magnetic resonance images in these animals demonstrate only bilateral periventricular lesions, manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance images reveal that small cortical lesions are also present ipsilateral to the carotid occlusion. These cortical lesions, at histologic analysis, are depleted of neurons.21

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS IN RODENT MODELS OF PVL

Pharmacologic manipulation of premyelinating oligodendroglial glutamate receptors is a promising method of PVL therapy. In neonatal rats subjected to hypoxia after unilateral carotid occlusion, the severity of periventricular depletion of premyelinating oligodendroglia is diminished by systemic administration of NBQX (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sullamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione) or topiramate immediately after the hypoxic episode.22,23 Both of these drugs inhibit AMPAR–mediated calcium loading and mitochondrial dysfunction. In vitro experiments with oligodendroglial lineage cultures have shown marked antiexcitotoxic effects of specific inhibitors of GluR2-free AMPARs18 and activators of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors24; however, the in vivo efficacy of these drugs in PVL models has not yet been evaluated. The recent discovery that cells of the oligodendroglial lineage in vivo, though not in vitro, express, highly calcium-permeable N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptors (NMDARs)25 and that ischemia in adult white matter causes NMDAR-mediated calcium accumulation in myelin and myelin disruption26 argues that NMDAR blockers should also be evaluated in PVL. A cautionary note, however, is that in vivo administration of high affinity NMDAR blockers can induce apoptosis of immature neurons. Low-affinity use-dependent NMDAR blockers such as memantine may be safer.

A second potential method of PVL therapy is prevention of free radicals and inflammatoy mediators from killing premyelinating oligodendroglia. For example, pretreatment in the third trimester of gestation of maternal rats with the antioxidant and glutathione precursor N-acetylcysteine inhibits central nervous system induction of proinflammatory cytokines and diminishes loss of oligodendroglial progenitors elicited by administration of lipopolysaccharide.27

Because glutamate, free radicals, and proinflammatory cytokines all have a role in the pathophysiology of PVL, treatments that inhibit microglial activation and thereby prevent production of these toxic molecules might be particularly useful in preventing or ameliorating PVL. Minocycline, a second-generation tetracycline derivative, crosses the blood-brain barrier and has a proved clinical track record as an antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drug. Minocycline suppresses microglial activation and has demonstrated neuroprotective qualities in a variety of neurologic disease models including experimental PVL.28,29 However, 2 observations argue for caution before administering minocycline to prevent PVL in premature infants. First, minocycline suppresses oligodendroglial regeneration from progenitors in a myelinotoxic model system,30 and second, in a large stage 3 trial in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, weakness unexpectedly progressed more rapidly in patients receiving minocycline than in control subjects receiving placebo.31

Rather than inhibiting microglial activation, which may exert deleterious as well as desired consequences for the oligodendroglial lineage, a more desirable approach may be to identify drugs that exert exclusively trophic effects on premyelinating oligodendroglia and immature neurons, thus enhancing their capacity to resist oxidant, excitotoxic, and inflammatory mediator-induced damage. A candidate for this role is erythropoietin, which antagonizes the toxic effects on oligodendroglial and neuronal lineages of free radicals, excitotoxins, and inflammatory mediators and is efficacious in both lipopolysaccharide- and ischemia-induced PVL models.32,33

TRANSLATION OF PVL THERAPIES FROM ANIMAL MODELS TO PREMATURE INFANTS

In comparison with PVL therapeutic investigations in large animals such as fetal lambs and newborn piglets, modeling the effects of interventions on PVL in rodents is straightforward and inexpensive. Mouse PVL models, in particular, have the important advantage that contributions of specific genes to the disease process can readily be investigated by knockout and overexpression techniques. However, a significant limitation of rodent PVL models is that cerebral white matter in rats and mice comprises less than 15% of the brain volume, whereas white matter in human beings or nonhuman primates comprises more than 50% of the brain volume. For faithful preclinical modeling of novel therapeutic interventions such as glutamate receptor antagonists, inhibitors of microglial activation, and oligodendrotrophic proteins in PVL, the animal chosen ideally should have a large enough volume of cerebral hemispheric white matter to enable study of both focal and diffuse components of PVL at acute, organizing, and chronic phases of evolution because the pathogenetic mechanisms in play at each stage may be different. In addition, the anatomic and functional maturation of cerebral vasculature should mirror that in the human infant. Functional studies of surviving animals should quantify motor and perceptual deficits to round out the suitability of the model. Only when the preponderance of these features is present can we be confident that results obtained with a given model will be translatable to premature infants at risk of PVL.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (Dr Deng) and by grants RO1 ES015988 (Dr Deng) and RO1 NS025044 (Dr D. Pleasure) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Deng had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Acquisition of data: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Analysis and interpretation of data: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Drafting of the manuscript: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Statistical analysis: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Obtained funding: Deng and D. Pleasure. Administrative, technical, and material support: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure. Study supervision: Deng, J. Pleasure, and D. Pleasure.

Additional Contributions: Sandra Gorges, MD, Department of Radiology, UC Davis School of Medicine provided the radiologic images.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

References

- 1.Back SA, Riddle A, McClure MM. Maturation-dependent vulnerability of perinatal white matter in premature birth. Stroke. 2007;38(2 suppl):724–730. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254729.27386.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuillen PS, Ferreiro DM. Perinatal subplate neuron injury: implications for cortical development and plasticity. Brain Pathol. 2005;15(3):250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vries LS, Van Haastert I-LC, Rademaker KJ, Koopman C, Groenendaal F. Ultrasound abnormalities preceding cerebral palsy in high-risk preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2004;144(6):815–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inder TE, Huppi PS, Warfield S, et al. Periventricular white matter injury in the premature infant is followed by reduced cerebral cortical gray matter volume at term. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(5):755–760. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<755::aid-ana11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagae LM, Hoon AH, Jr, Stashinko E, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in children with periventricular leukomalacia: variability of injuries to white matter tracts. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(7):1213–1222. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vollmer B, Roth S, Baudin J, Stewart AL, Neville BG, Wyatt JS. Predictors of long-term outcome in very preterm infants: gestational age versus neonatal cranial ultrasound. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1108–1114. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins MP, Lorenz JM, Jetton JR, Paneth N. Hypocapnia and other ventilation-related risk factors for cerebral palsy in low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(6):712–719. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200112000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiswell TE, Graziani LJ, Kornhauser MS, et al. Effects of hypocarbia on the development of cystic periventricular leukomalacia in premature infants treated with high-frequency jet ventilation. Pediatrics. 1996;98(5):918–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galli KK, Zimmerman RA, Jarvik GP, et al. Periventricular leukomalacia is common after neonatal cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(3):692–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.09.053. published correction appears in J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(3):498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinney HC, Panigrahy A, Newburger JW, Jonas RA, Sleeper LA. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in infants with congenital heart disease dying after cardiac surgery. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110(6):563–578. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soul JS, Hammer PE, Tsuji M, et al. Fluctuating pressure-passivity is common in the cerebral circulation of sick premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(4):467–473. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31803237f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. Anatomic analysis of blood vessels in germinal matrix, cerebral cortex, and white matter in developing infants. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(1):117–124. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000130472.30874.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billiards SS, Haynes RL, Folkerth RD, et al. Development of microglia in the cerebral white matter of the human fetus and infant. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497(2):199–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.20991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monier A, Adle-Biassette H, Delezoide AL, Evrard P, Gressens P, Verney C. Entry and distribution of microglial cells in human embryonic and fetal cerebra cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(5):372–382. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180517b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinsella JP, Cutter GR, Walsh WF, et al. Early inhaled nitric oxide therapy in premature newborns with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):354–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowther CA, Hilier JE, Doyle LW, Haslam RR Australasian Collaborative Trial of Magnesium Sulphate (ACTOMg SO4) Collaborative Group. Effect of magnesium sulfate given for neuroprotection before preterm birth: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2669–2676. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyatt JS, Gluckman PD, Liu PY, et al. Determinants of outcomes after head cooling for neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):912–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh T, Beesley J, Itoh A, et al. AMPA glutamate receptor-mediated calcium signaling is transiently enhanced during development of oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem. 2002;81(2):390–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horiuchi M, Itoh A, Pleasure D, Itoh T. MEK-ERK signaling is involved in interferon-gamma-induced death of oligodendroglial progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(29):20095–20106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQuillen PS, Sheldon RA, Shatz CJ, Ferreiro DM. Selective vulnerability of subplate neurons after early neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3308–3315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03308.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Wu EX. Detection of cortical gray matter lesion in the late phase of mild hypoxic-ischemic injury by manganese enhanced MRI. Neuroimage. 2008;39(2):669–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Follett PL, Rosenberg PA, Volpe JJ, Jensen FE. NBQX attenuates excitotoxic injury in developing white matter. J Neurosci. 2000;20(24):9235–9241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09235.2000. published correction appears in J Neurosci. 2001;21 (5):1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Follett PL, Deng W, Dai W, et al. Glutamate receptor-mediated oligodendrocyte toxicity in periventricular leukomalacia: a protective role for topiramate. J Neurosci. 2004;24(18):4412–4420. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0477-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng W, Wang H, Rosenberg PA, Volpe JJ, Jensen FE. Role of metabotropic glutamate receptors in oligodendrocyte excitotoxicity and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(20):7751–7756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307850101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziskin JL, Nishiyama A, Rubio M, Fukaya M, Bergles DE. Vesicular release of glutamate from unmyelinated axons in white matter. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(3):321–330. doi: 10.1038/nn1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Káradóttir R, Cavelier P, Pergersen LH, Attwell D. NMDA receptors are expressed in oligordendrocytes and activated in ischaemia. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paintlia MK, Paintlia AS, Barbosa E, Singh I, Singh AK. N-acetylcysteine prevents endotoxin-induced degeneration of oligodendrocyte progenitors and hypomyelination in developing rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78(3):347–361. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan LW, Pang Y, Lin S, et al. Minocycline reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced neurological dysfunction and brain injury in the neonatal rat. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82(1):71–82. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai Z, Lin S, Fan LW, Pang Y, Rhodes PG. Minocycline alleviates hypoxic-ischemic injury to developing oligodendrocytes in the neonatal rat brain. Neuroscience. 2006;137(2):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li WW, Setzu A, Zhao C, Franklin RJM. Minocycline-mediated inhibition of microglia activation impairs oligodendrocyte progenitor cell responses and remyelination in a non-immune model of demyelination. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;158(1-2):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon PH, Moore DH, Miller RG, et al. Western ALS Study Group. Efficacy of minocycline in patients with amyptrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase III randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. (12) doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller M, Yang J, Griesmaier E, et al. Erythropoietin is neuroprotective against NMDA-receptor-mediated excitotoxic brain injury in newborn mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24(2):357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumral A, Baskin H, Yesilirmak DC, et al. Erythropoietin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced white matter injury in the neonatal rat brain. Neonatology. 2007;92(4):269–278. doi: 10.1159/000105493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]