Abstract

Both bipolar and hemiarthroplasty have been used to treat rotator cuff arthropathy (RCA) of the shoulder in patients with low functional demands. In this study, 41 patients treated with either a bipolar or hemiarthroplasty were selected retrospectively to detect possible differences in the functional outcome and to evaluate radiological properties of the implants. Patients were examined before and 30 ± 6 months after surgery. There were no differences in the Constant scores between the groups treated with hemiarthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty, 58.9 ± 13.1 points and 55.8 ± 13.5 points, respectively (P = 0.457). We found a significant increase in abduction postoperatively in both groups (P = 0.041 bipolar, P = 0.000 hemiarthroplasty) but without statistical significance between the hemiarthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty groups (P = 0.124, F = 2.6). This result is related in the bipolar group due to movement between the shell and inner head (P = 0.042) and in the hemiarthroplasty group due to movement between the humeral head component and the glenoid (P = 0.000). In conclusion, we found that both hemiarthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty are effective treatment options for carefully selected patients with RCA and low functional demands, with no differences between the groups.

Résumé

Pour traiter les lésions dégénératives de l’épaule avec lésions de la coiffe (RCA), on a pu proposer chez des patients dont la demande fonctionnelle était peu importante soit une prothèse totale, soit une prothèse unipolaire. 41 patients ont ainsi été traités. Dans le cadre d’une étude rétrospective, nous avons voulu mettre en évidence les différences fonctionnelles de ces patients ainsi que l’évolution radiologique de ces implants. Ces patients ont été examinés avant l’intervention et en moyenne 30 mois ± 6 mois après la chirurgie. Il n’y avait pas de différence dans le niveau du score de Constant dans le groupe traité par hémi arthroplastie ou par prothèse totale. 58.9 ± 13.1 et 55.8 ± 13.5, P = 0.457. Nous avons par contre trouvé une amélioration de l’adduction post opératoire dans les deux groupes de patients, P = 0.041 prothèse totale, P = 0.000 hémi arthroplastie mais sans différence significative entre les deux groupes, P = 0.124 et F = 2.6. Ces résultats sont secondaires dans le groupe des prothèses totales au mouvement constitué entre cupule glénoïdienne et la tête (P = 0.042) et, dans le groupe d’hémi arthroplastie entre la tête humérale et la glène (P = 0.000). En conclusion, chez les patients présentant une RCA avec une demande fonctionnelle peu importante un traitement par prothèses totales ou prothèses unipolaires est possible avec un résultat significativement satisfaisant sans différence entre les deux groupes.

Introduction

The current surgical management of a rotator cuff arthropathy (RCA) offers a wide range of options, such as arthroscopic debridement [1], arthroplasty [7, 23, 24], fusion and resection arthroplasty [2], with variable results.

Good short- and mid-term results for pain relief and improved function have been reported with the use of a reversed total shoulder prosthesis, developed by Grammont and Baulot [7]. The design of the implant leads to a medialised and distalised centre of rotation of the gleno-humeral joint and, subsequently, to an increased lever arm and pretension of the deltoid muscle. However, several problems have been reported with the use of a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, e.g. glenoid component fixation [5], infection [12] or inferior notching [17], which may lead to early failure of the prosthesis. Therefore, and because of the absence of long-term results, reverse shoulder total prostheses are mainly recommended for elderly patients and for the treatment of severe shoulder dysfunction [8].

Shoulder hemiarthroplasty has been one alternative surgical treatment of RCA. However, the functional results are inferior when compared with patients with an intact rotator cuff and they may be complicated by a progressive glenoid erosion, subacromial wear and instability [13].

The development of bipolar shoulder replacements, first described by Swanson et al. [19, 20], was aimed at minimising these complications [24]. The theoretical advantages of the birotational design of this prosthesis was denoted in an improved function, reduced bone loss of the glenoid and acromion when compared with shoulder hemiarthroplasty and a relatively simple implantation technique. Despite the claimed potential advantages, the functional results reported following bipolar arthroplasty have been inconsistent [4, 20, 22, 24].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the clinical results of a bipolar shoulder arthroplasty with those of hemiarthroplasty in patients treated for RCA. Furthermore, we investigated the intraprosthetic movement during abduction to provide a better understanding of the course of motion of both the prosthesis and the potential effects of glenoid and acromion wear.

Material and methods

Patients

The basis of this investigation was a series of 58 arthroplasties performed from 1st May 2001 to 30th October 2004 for the diagnosis of RCA. In 17 patients, reversed shoulder prostheses were implanted. Due to the risk of an unstable fixation of the glenoid component of the reversed shoulder prosthesis (preoperative radiological evaluation), the remaining 41 patients received either a bipolar shoulder arthroplasty (group 1) or a hemiarthroplasty (group 2). The decision of which patient received which prosthesis was made according to their medical record numbers. Patients with odd medical numbers were placed in group 1 and patients with even medical numbers were placed in group 2. The indications for operation were pain, loss of function and failure of conservative treatment. Preoperative confirmation of a massive and irreparable rupture of the complete cuff was made by a magnetic resonance scan. Additionally, conventional radiographs of the shoulder (see below) demonstrating RCA were graded I A, I B and II A, as described by Seebauer et al. [16] and Visotsky et al. [21].

In the group 1, there were 14 woman and 7 men. At the time of surgery, patients ranged in age from 56 to 79 years (mean 67.8 years; SD±7.8). Twelve right shoulders and 9 left shoulders were treated and 13 of the shoulders were on the dominant side.

Group 2 consisted of 13 woman and 7 men. Their age ranged from 56 to 79 years (mean 66.2 years; SD±7.8) Ten right shoulders and 10 left shoulders were treated and the right side was dominant in all patients.

None of the shoulders had undergone previous surgical procedures and no other significant neuromuscular or skeletal pathologies were present.

Surgical technique

All patients were operated on in a beach chair position with the use of a combination of general and regional anaesthesia. All operations were performed by the two authors via a standard deltopectoral approach. After incision, a debridement of irreparable rotator cuff tissue was done. After preparation of the humerus, either a hemiarthroplasty (Aequalis prosthesis, Tornier, Montbonnot, France) or a bipolar shoulder arthroplasty (Bipolar prosthesis, Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) was implanted. The glenoid was not reamed. All prostheses were inserted with cement.

After surgery, all patients were immobilised in a sling and they gradually discontinued using it over a period of 5 weeks. All patients underwent the department’s standard inpatient rehabilitation program for 7 days and an additional outpatient rehabilitation program continued for 6 weeks after discharge.

Radiological assessment

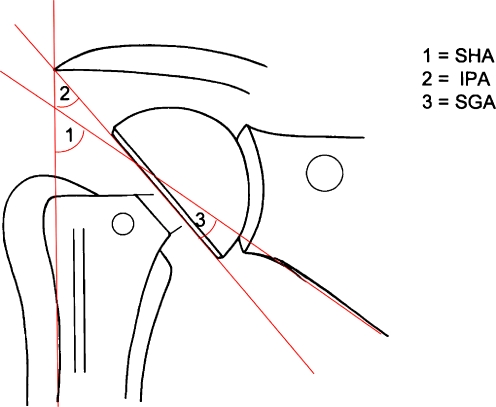

All patients were evaluated preoperatively with radiographs of the shoulder in the antero-posterior view with the humerus in neutral rotation, and axillary and scapular view confirming the presence of bony changes. Immediately after surgery, the patients had true antero-posterior radiographs in neutral rotation of the humerus. Additionally, axillary radiographs were performed during the follow-up to assess component position and check for signs of prosthetic loosening. Patients with a bipolar shoulder replacement were investigated fluoroscopically in abduction. The position of the implants of the bipolar prosthesis were assessed at 0° and 90° (or maximal abduction). Radiographic angles were measured according to the study of Hing et al. [9] (Fig. 1). The lateral border of the scapula and the lateral border of the humeral stem were used to determine the extent of the gleno-humeral range during movement (scapular-humeral angle, SHA). The base of the shell of the bipolar prosthesis and the lateral border of the humeral stem were used to determine the movement between the stem and the shell in the neutral position and full abduction (intraprosthetic angle, IPA). The angle between the lateral border of the scapula and the base of the shell was used to calculate the shell–glenoid range in both positions of the arm (shell–glenoid angle, SGA) movement.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the measured angles. SHA=scapular-humeral angle, IPA=intraprosthetic angle, SGA=shell–glenoid angle

Clinical evaluation

All patients in this study were evaluated with use of the Constant score, adjusted to age and gender [3] and the DASH (disability of the arm, shoulder and hand) score [10]. In addition, the active anteversion, the active abduction and the active external rotation with the arm at the side were recorded. Complications were noted.

The follow-up in group 1 ranged from 25 to 56 months (mean 33.1 months; SD±7.3) and in group 2 from 30 to 54 months (mean 35.6 months; SD±4.3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired two-tailed t-test to assess differences between the groups and a paired two-tailed t-test was used to compare the pre- and postoperative values for both groups. With regard to the radiological assessment, the statistical analysis was performed with a repeated measurement analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the SHA and SGA in both groups. The inner subject factor was task (0° and maximal abduction) and group (hemiarthroplasty or bipolar arthroplasty). A paired two-tailed t-test was used to compare the measurements of intraprosthetic movement (IPA). A significance level less than 0.05 was assumed. We used SPSS statistical software, version 13.0, for Windows, for all calculations. Unless specified otherwise, the results are given as mean±standard deviation (SD).

Results

Subjects

There were no significant differences between the groups with regard to age (P = 0.564), gender (P = 0.585) and follow-up (P = 0.186). The preoperative functional status of the patients in both groups are represented in Table 1, which also shows no differences.

Table 1.

Preoperative and postoperative values of Constant score, DASH score and range of movement in both groups

| Preoperative | Postoperative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | P value | Bipolar arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | P value | |

| Pain (points) | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 1.5 ± 2.3 | 0.664 | 8.9 ± 3.8 | 7.3 ± 3.0 | 0.137 |

| Activity (points) | 5.8 ± 2.7 | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 0.237 | 9.3 ± 3.4 | 10.8 ± 2.6 | 0.121 |

| Motion (points) | 14.3 ± 4.7 | 16.0 ± 4.5 | 0.245 | 20.9 ± 6.3 | 18.9 ± 6.1 | 0.298 |

| Strength (points) | 4.4 ± 3.4 | 5.3 ± 2.2 | 0.338 | 5.1 ± 4.2 | 6.3 ± 3.5 | 0.324 |

| Total (points) | 25.7 ± 7.7 | 29.5 ± 6.4 | 0.099 | 44.3 ± 10.6 | 42.8 ± 10.2 | 0.656 |

| Total adjusted (points) | 34.6 ± 11.1 | 39.6 ± 9.8 | 0.136 | 58.9 ± 13.1 | 55.8 ± 13.5 | 0.457 |

| DASH (points) | 61.4 ± 12.5 | 62.8 ± 10.8 | 0.711 | 46.4 ± 14.7 | 47.6 ± 11.9 | 0.772 |

| Anteversion (°) | 58.1 ± 20.7 | 67.7 ± 21.7 | 0.154 | 69.3 ± 22.4 | 78.5 ± 25.8 | 0.230 |

| Abduction (°) | 52.6 ± 20.2 | 55.75 ± 16.1 | 0.589 | 60.5 ± 23.3 | 66.0 ± 19.3 | 0.415 |

| External rotation (°) | 17.8 ± 14.2 | 21.7 ± 18.0 | 0.448 | 34.3 ± 18.6 | 37.0 ± 12.6 | 0.589 |

Data are given as mean±standard deviation

Clinical results

The postoperative results demonstrated highly significant improvements compared with the preoperative values in most parameters following both types of shoulder arthroplasty (Table 2). However, we could not detect an improvement of strength during the follow-up in the entire series.

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative values of Constant score, DASH score and range of movement in the entire series

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain (points) | 1.38 ± 2.1 | 7.9 ± 3.5 | 0.000 |

| Activity (points) | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 9.7 ± 3.3 | 0.000 |

| Motion (points) | 14.6 ± 4.9 | 19.3 ± 6.6 | 0.000 |

| Strength (points) | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 5.6 ± 3.7 | 0.197 |

| Total (points) | 26.7 ± 8.2 | 42.1 ± 12.3 | 0.000 |

| Total adjusted (points) | 35.9 ± 11.6 | 55.5 ± 15.6 | 0.000 |

| DASH (points) | 59.8 ± 15.2 | 45.4 ± 14.4 | 0.00 |

| Anteversion (°) | 60.9 ± 22.3 | 71.6 ± 25.4 | 0.007 |

| Abduction (°) | 52.5 ± 18.9 | 61.3 ± 22.2 | 0.004 |

| External rotation (°) | 19.6 ± 15.4 | 34.7 ± 15.6 | 0.000 |

Data are given as mean±standard deviation

There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups after surgery with respect to the Constant score, DASH score and active range of motion (Table 1).

The mean operative time was 116 ± 41 min for the bipolar shoulder arthroplasty group and 125 ± 25 min for the hemiarthroplasty group (P = 0.151).

Complications

Postoperatively, a haematoma of the shoulder developed in one patient in the bipolar group, which resolved without operative treatment (an aspiration was performed). One patient in the hemiarthroplasty group had a temporary incomplete brachial plexus neuropathy, possibly caused by a local haematoma after the plexus anaesthesia, which resolved 2 months after surgery.

Radiological results

There have been no radiolucent lines around the humeral implant or an osteolysis. In 4 patients of the hemiarthroplasty group and 3 patients in the bipolar arthroplasty group, we could detect a mild gleno-humeral subluxation, which means that there was an anterior translation of less than 25% with respect to the amount of translation of the centre of the prosthetic head relative to the centre of the glenoid.

Four shoulders in group 1 and 6 shoulders in the group 2 had erosion of the glenoid. We detected a superior migration of the humeral component with an erosion of the acromion in 4 patients in the hemiarthroplasty group and in 2 patients in the bipolar group. Despite the radiological findings and a moderate complaint of pain, no patients required a reoperation during the follow-up.

The results of the evaluation of the SHA, IPA and SGA with the shoulder positioned either in 0° abduction or in 90° abduction are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of scapular-humeral angle (SHA), intraprosthetic angle (IPA) and shell–glenoid angle (SGA) in the patients in neutral position (0° abduction) and 90° abduction (or maximal abduction)

| Bipolar arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° abduction | 90° abduction | 0° abduction | 90° abduction | |

| SHA (°) | 61.7 ± 12.4 | 70.2 ± 10.3 | 50.5 ± 5.2 | 71.8 ± 12.2 |

| IPA (°) | 26.5 ± 14.8 | 36.9 ± 15.8 | n. a. | n. a. |

| SGA (°) | 39.3 ± 16.4 | 35.0 ± 11.9 | 9.5 ± 6.9 | 28.5 ± 6.1 |

Data are given as mean±standard deviation (n.a.=not applicable)

We demonstrated a significant increase of the SHA in both groups (P = 0.041 group 1, P = 0.000 group 2) but without statistical significance between the hemiarthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty groups (P = 0.124, F = 2.6). With respect to the SGA, measurements obtained in the bipolar group show no differences between the neutral position and maximal abduction of the shoulder (F = 0.464). In contrast, the SGA measurements were significantly higher in maximal abduction of the shoulder when compared with the neutral position in the hemiarthroplasty group (F = 0.000). In the bipolar group, the IPA in maximal abduction of the shoulder was higher than at 0° abduction (F = 0.042).

Discussion

Today, despite new concepts, the surgical treatment of patients with RCA with shoulder arthroplasty is, at least in part, an unsolved problem. Shoulder replacement in cases with a deficient cuff requires the restoration of shoulder function and stable fixation of prosthesis components. Total shoulder arthroplasty has been shown to fail as a result of glenoid loosening, instability and subacromial wear [6, 14]. As an alternative, hemiarthroplasty has been reported to provide acceptable clinical results in elderly patients with low functional demands [23] and to avoid the problems of an early failure of the prosthesis due to the glenoid component loosening. On the other hand, the humeral head component can also lead to a progressive glenoid and/or acromion erosion and, subsequently, to a failure of the prosthesis. As a consequence, the modification of shoulder hemiarthroplasties with the concept of a specially designed cuff tear arthropathy head (CTA, De Puy) was developed with the theoretical advantages of an increased surface area for the osseous contact and an decreased impingement of the greater tuberosity [21]. This design can also provide a reduction of pain and preserve shoulder function, although the results are inferior when compared to patients with an intact rotator cuff [13].

In this study, we compared the clinical results of patients with RCA who were surgically treated either with a bipolar arthroplasty or a hemiarthroplasty. Additionally, we performed a radiological investigation of both types of prostheses in the neutral position and in maximal abduction of the shoulder to provide a better understanding of the movement of the implants.

To our knowledge, this is the first age—and gender—matched study comparing the results of hemi- or bipolar arthroplasty in patients with RCA. In accordance with several other studies [11, 13, 23, 24], our results show a significant improvement of shoulder function and pain relief in the entire investigation series. However, we could not detect a superiority of the bipolar prosthesis with regard to shoulder function or pain relief when compared with the hemiarthroplasty group. In particular, we could not detect an improved strength in the bipolar group as evidence for an improved deltoid function based on a large humeral head and increased lateral offset. Therefore, the potential advantages of an improved function due to the birotational design are not supported by our investigation.

Few studies deal with the radiographic evaluation of the movement of the bipolar prosthesis and the results are controversial [9, 18]. The radiological investigation of the movement in the bipolar group demonstrated an increase of the intraprosthetic angle of about 10° during abduction of the arm. Although relatively small, this result supports the assumption that a motion occurred between the bipolar cup and the inner head articulation. Similar to our results, Hing et al. detected intraprosthetic movement even 3 years after surgery, although they showed that the range of motion at the interprosthetic interface significantly decreased during the follow-up period [9]. These data point towards a potential conceptual weak point of the bipolar design. The small radius of the inner head, which serves as the primary centre of rotation, restricts the gleno-humeral motion due to the small radius of gyration. Furthermore, we found that the angle between the bipolar shell and the glenoid remains unchanged during abduction, which indicates that no movement occurred between the shell and the glenoid. In contrast, the radiological investigation in the hemiarthroplasty group shows an increase of gleno-humeral abduction of about 20°, which was based on a movement between the humeral head component and the scapula. However, in our study, we did not find that superior bone wear was increased in the hemiarthroplasty group when compared with the bipolar group. Therefore, the postulated reduced glenoid wear and subsequently lower rate of failure of bipolar prostheses could not supported by our results.

However, our investigation has some limitations. First, our follow-up assessment at 35 months prevents any conclusion with respect to the long-term results of both prostheses. We cannot exclude the fact that our follow-up was too short to detect possible differences in the survivorship of both prosthesis.

Another critical notation is the limited number of patients in both groups. However, the number of patients in our investigation is comparable with that of other studies [4, 13, 15, 23, 25], which indicate a proper selection of comparable subjects.

In summary, this study demonstrates that bipolar arthroplasty as well as hemiarthroplasty are effective treatment options for carefully selected patients with RCA and low functional demands. During the follow-up in our study, we could not detect any differences with regard to shoulder function, pain relief and rate of complications between both replacement types.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Deutsche Arthrose-Hilfe e.V., Frankfurt, Germany.

References

- 1.Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic treatment of massive rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;390:107–118. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cofield RH. Shoulder arthrodesis and resection arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 1985;34:268–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duranthon LD, Augereau B, Thomazeau H, et al. Bipolar arthroplasty in rotator cuff arthropathy: 13 cases (in French) Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot. 2002;88:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, et al. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1697–1705. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FA., 3rd Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty. Association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplast. 1988;3:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(88)80051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics. 1993;16:65–68. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1742–1747. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hing C, Boddy A, Griffin D, et al. A radiological study of the intraprosthetic movements of the bipolar shoulder replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DH, Niemann KM. Bipolar shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:17–22. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.110515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1814–1822. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW, Rowland CM, Cofield RH. Instability after shoulder arthroplasty: results of surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:622–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarris IK, Papadimitriou NG, Sotereanos DG. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty for chronic rotator cuff tear arthropathy. J Arthroplast. 2003;18:169–173. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seebauer L, Walter W, Keyl W. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of defect arthropathy. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00064-005-1119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, et al. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:388–395. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stavrou P, Slavotinek J, Krishnan J. A radiographic evaluation of birotational head motion in the bipolar shoulder hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson AB, Groot Swanson G, Maupin BK, et al. Bipolar implant shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1986;9:343–351. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19860301-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson AB, Groot Swanson G, Sattel AB, et al. Bipolar implant shoulder arthroplasty. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:227–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visotsky JL, Basamania C, Seebauer L, et al. Cuff tear arthropathy: pathogenesis, classification, and algorithm for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(Suppl 2):35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vrettos BC, Wallace W, Neumann L. Bipolar shoulder arthroplasty for rotator cuff arthropathy: a preliminary report and video fluoroscopy study [abstract] J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80-B(Supplement I):106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams GR, Jr, Rockwood CA., Jr Hemiarthroplasty in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:362–367. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(96)80067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worland RL, Jessup DE, Arredondo J, Warburton KJ. Bipolar shoulder arthroplasty for rotator cuff arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:512–515. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(97)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuckerman JD, Scott AJ, Gallagher MA. Hemiarthroplasty for cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:169–172. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(00)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]