Abstract

In previous studies we observed a proximo-distal gradient of lesion frequencies along the limb, with the distal joints being the most often affected. This suggests an associated effect of environmental factors on the most exposed joints. On a population of 820 children (mean age 13 years) of endemic areas distributed in groups of healthy and severity stages I to III of KBD (Kashin-Beck disease), the effects of different working activities were studied. Heavy work like that of a ploughman were compared to light physical work, e.g. school children, and exposure to cold and history of frostbite were also considered. The most severe stages, II and III, were present in 72% of the ploughman vs. 29% of the schoolchildren, 70% of the shepherds vs. 30% (p < 0.001) of the schoolchildren, and in 65% of the shepherds working in winter vs. 40% of those working in the other seasons (p < 0.001). In the group with history of frostbite, 58% present the severest stages vs. 40% without (p < 0.001). The results confirm a highly significant relation between microtrauma and cold and the severity of the KBD alterations.

Résumé

Dans nos précédentes études, nous avions observé un gradient de fréquence proximo-distale des lésions le long des membres, les articulations distales étant les plus souvent atteintes. Ceci suggère un effet associé des facteurs environnementaux sur les articulations les plus exposées. Sur une population de 820 enfants (âge moyen 13ans) provenant de régions endémiques et distribués en groupes sains et de stades de gravité de la maladie de KASHIN-BECK s´échelonnant de I à III, nous avons étudié les effets de différents types d´activités. Les travaux lourds, comme celui de laboureur, ont été comparés à une activité plus légère telle que celle d´écolier. Les stades les plus sévères (II et III) sont présents chez 72% des laboureurs contre 29% chez les écoliers, chez 70% des bergers contre 30% des écoliers (p<0.001) et chez 65% des bergers travaillant en hiver contre 40% chez ceux travaillant pendant les autres saisons (p<0.001). Dans le groupe présentant des antécédents de gelure, 58% présentent les stades les plus sévères contre 40% dans le groupe sans antécédents (p<0.001). Ces résultats confirment une relation très hautement significative entre les microtraumas et l´exposition au froid et la sévérité des lésions de la maladie de Kashin-Beck..

Introduction

Kashin-Beck disease (KBD) is an endemic disabling osteoarticular disease involving growth cartilage and resulting in severe alterations of the joints [1, 10, 15]. The clinical manifestations appear between five and 15 years old. Three million people are affected in Tibet, China and south-east Siberia. Aetiological hypotheses include micotoxin in stored barley grains [2, 3, 5, 6], Selenium (Se) deficiency [4, 12, 13] and excess of fulvic acid in drinking water [9].

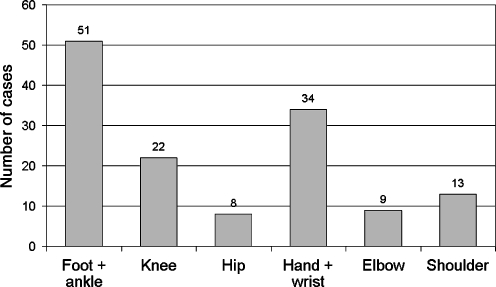

The clinical manifestations and radiological lesions in Kashin-Beck disease in the Tibet Autonomous Region were described with their gravity scale in previous papers [7, 8, 11]. One of the most characteristic observations is the proximo-distal gradient along the apendicular skeleton in terms of frequency and severity of joint involvement [7]. The most distal joints of the upper and lower limbs are the most often and most severely affected, especially noticeable in the lower limb (Fig. 1). These observations, in parallel with the histological findings, suggest an effect of the exposure of the distal joints to environmental factors which could aggravate the lesions of the disease.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of the radiological alterations by anatomic location on a population of 105 Kashin-Beck disease (KBD) cases [3]

Materials and methods

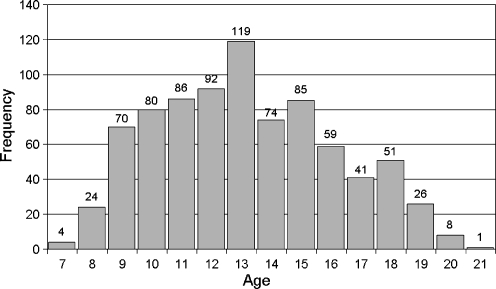

The population studied includes 820 inhabitants from three prefectures and five counties in endemic areas distributed as follows: prefecture of Shigatse, county Shetome 197; prefecture of Lhoca, counties Neudong 259 and Sangri 42; and the prefecture of Lhasa, counties Lundrup 101 and Nyemo 221. The whole population includes 24% healthy people, 33% stage I, 18% stage II and 25% stage III, following our clinical grading [11]. The mean age was 13 years (range 7–21; Fig. 2). There were 397 girls (48%) and 423 boys (52%). In an attempt to identify the effect of the environment on the evolution of KBD, we selected different activities which represent different levels of exposure to cold and microtrauma (light or heavy work). For the different working habits, the seasons were recorded. History of frostbite was also considered. The survey was conducted systematically in the villages by members of the research team and an interpreter. Statistical analyses were conducted with the t-test and chi-squared test.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of ages in the population studied (n = 820)

Results

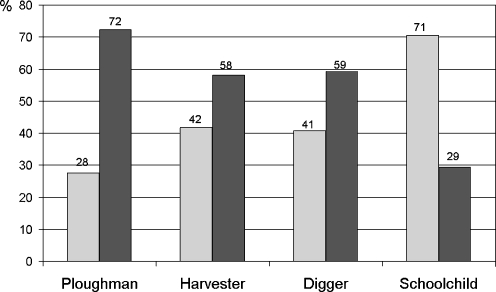

A first analysis compares the different working habits prevailing for each individual without consideration of the seasons. The whole population was divided into two groups. The first group (n = 472) includes no symptoms and stage I KBD (early manifestation of the disease) [11], and the second group (n = 348) includes stages II and III KBD. The prevalence of those groups was compared among ploughmen, harvesters, diggers and school children. The chi-squared test on the proportions gives a p -value less than 0.001. Figure 3 gives the percentage of each group (stages 0–I compared to stages II–III) in the different activities.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of stages 0 and I (grey) compared to stages II and III (black) in the different populations of workers (n = 820)

Clearly, the heaviest work, ploughman, gives the highest percentage of severe grading of KBD and, conversely, for the school children.

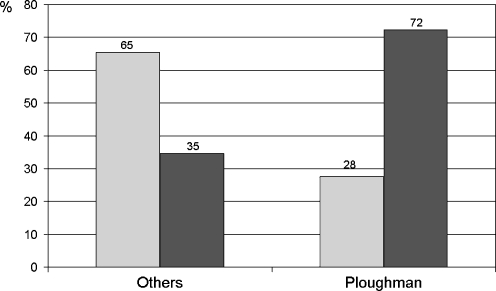

Comparison between the ploughmen and all other activities confirms the role of the workload (p < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of stages 0 and I (grey) compared to stages II and III (black) in the population of ploughmen and in the total population of the other workers

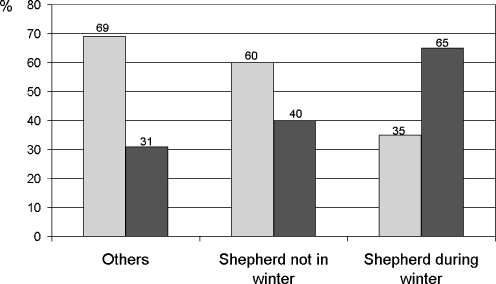

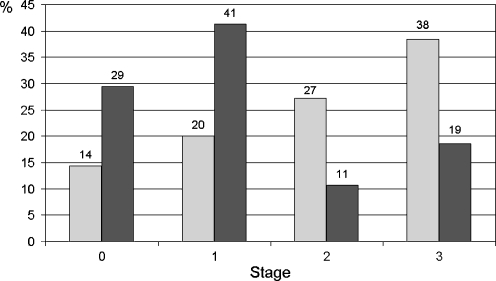

To analyse the impact of the seasons, we compared the shepherds working in all seasons except winter with those working in winter and with the others activities. Figure 5 illustrates the differences with a p < 0.001. The shepherds working in winter suffer from the most severe lesions. Figure 6 compares the prevalence of the different stages (0–III) among shepherds and school children active during the winter. A clear trend shows the increasing prevalence of the late stage of the disease for the shepherds and the opposite situation for the school children (p < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the different percentages of the stages 0–I and II–III in the groups of shepherds active in winter, shepherds working in other seasons, and the other workers (n = 820)

Fig. 6.

Distribution of the shepherds (grey) as percentage of all the shepherds among the different stages of severity compared to the distribution of the schoolchildren (n = 658)

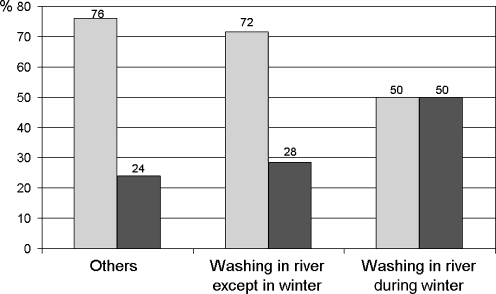

The same trend is observed with the villagers washing their clothes in the river in different seasons (p < 0.001; Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Percentage of stages 0–I (grey) and stages II–III (black) in population doing the laundry in the river during the winter, in the other seasons, and the other workers (n = 820)

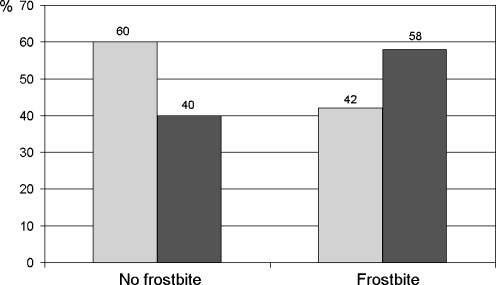

Finally, the consequences of a history of frostbite are compared with the prevalence of the lesions. The results show an increased severity staging for those mostly exposed to frost (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Percentage of stages 0–I (grey) and stages II–III (black) in the population with and without a history of frostbite (n = 820)

Conclusions

The mechanisms of Kashin-Beck disease are not yet clearly identified. However, the histological observation of small necrotic lesions in the cartilage of the growth plate [14] may explain the evolution of the disease. Also, since a good relation exists between mycotoxins produced by fungi in barley grain and the prevalence of KBD [2, 3, 5, 6], it is clear that a multifactorial aetiology should be considered.

The observation of a proximo-distal gradient of the lesions and their severity show that the most exposed joints to environmental factors present the worst lesions. This observation initiated this survey, aiming to compare the effects of cold exposure and microtrauma generated by heavy work. The results confirm a highly significant relation between environmental conditions such as microtrauma and frost and the severity of the lesions. These factors are not at the origin of the disease, but they appear to be responsible for its aggravation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to ackowledge the KBD Foundation.

References

- 1.Allander E (1994) Kashin-Beck disease. An analysis of research and public health activities based on a bibliography. Scand J Rheumatol (23):1849–1992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Chasseur C, Suetens C, Nolard N, Begaux F, Haubruge E. Fungal contamination in barley and Kashin-Beck disease in Tibet. Lancet. 1997;350:1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chasseur C, Suetens C, Michel V, Mathieu F, Begaux F, Nolard N, Haubruge E. A 4-year study of the mycological aspects of Kashin-Beck disease in Tibet. Int Orthop. 2001;25(3):154–159. doi: 10.1007/s002640000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chasseur C, Suetens C, Begaux F, Haubruge E, Wangla R, Rinchen L, Wangdu L, Claus W, Mathieu F (2008) The mineral deficiency hypothesis. In: Malaisse F, Mathieu F (eds) “Big Bone Disease”. Presse Agro de Gembloux, pp 101–103

- 5.Chasseur C, Lognay G, Suetens C, Rapten S, Gillet P, Kanyandekwe P, He L, Drolkar P, Wangla R, Begaux F, Haubruge E, Rinchen L, Wangdu L, Claus W, Mathieu F (2008) The fungal hypotheses. In: Malaisse F, Mathieu F (eds) “Big Bone Disease”. Presse Agro de Gembloux, pp 85–99

- 6.Haubruge E, Chasseur C, Debouck C, Begaux F, Suetens C, Mathieu F, Michel V, Gaspar C, Rooze M, Hinsenkamp M, Gillet P, Nollard N, Lognay G. The prevalence of mycotoxins in Kashin-Beck disease. Int Orthop. 2001;25(3):159–162. doi: 10.1007/s002640100240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinsenkamp M, Rippens F, Begaux F, Mathieu F, Maertelaer V, Lepeire M, Haubruge E, Chasseur C, Stallenberg B. The anatomical distribution of radiological abnormalities in Kashin-Beck disease. Int Orthop. 2001;25(3):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s002640100236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinsenkamp M, Mathieu F, Begaux F, Samdrup T, Stallenberg B (2008) Radiologic study. In: Malaisse F, Mathieu F (eds) “Big Bone Disease”. Presse Agro de Gembloux, pp 57–59

- 9.Grange M, Mathieu F, Begaux F, Durand MC. Kashin-Beck disease and drinking water in Central Tibet. Int Orthop. 2001;25(3):167–169. doi: 10.1007/s002640000194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathieu F, Hinsenkamp M (2008) Kashin-Beck disease. In: Malaisse F, Mathieu F (eds) “Big Bone Disease”. Presse Agro de Gembloux, pp 11–18

- 11.Mathieu F, Begaux F, Lan Z, Suetens C, Hinsenkamp M. Clinical characteristics of Kashin-Beck disease in Nyemo Valley, Tibet. Int Orthop. 1997;21(3):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s002640050139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno-Reyes R, Suetens C, Mathieu F, Begaux F, Zhu D, Rivera MT, Boelaert M, Neve J, Perlmutter N, Vanderpas J. Kashin-Beck osteoarthropathy in rural Tibet in relation to selenium and iodine status. New Engl J Med. 1998;339(16):1112–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno-Reyes R, Mathieu F, Boelaert M, Begaux F, Suetens C, Rivera MT, Nève J, Perlmutter N, Vanderpas J. Selenium and iodine supplementation of rural Tibetan children affected by Kashin-Beck osteoarthropathy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(1):137–44. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasteels JL, Liu F-D, Hinsenkamp M, Rooze M, Mathieu F, Perlmutter N. Histology of Kashin-Beck lesions. Int Orthop. 2001;25(3):151–154. doi: 10.1007/s002640000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokoloff L. The history of Kashin-Beck disease. NY State J Med. 1989;89(6):343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]