Abstract

In patients with congestive heart failure (CHF), a high prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing has been described. Cheyne-Stokes respiration (CSR) is present in up to 40% of patients with CHF. During the last decade, the medical treatment has been substantially improved. This study was designed to analyze the prognosis of CSR in modern-treated patients with CHF. For this purposes, in 57 patients with CHF who received modern treatment, a 5-year follow-up after initial full night polysomnography was performed. The mean follow-up period was 38 ± 18 months. Mean age was 62 ± 13 years and the mean ejection fraction was 25 ± 7 percent. Respiratory polygraphy revealed CSR with a respiratory disturbance index >5 per hour of sleep in 39 of 57 patients. Twelve patients died. CSR was only characterized by a tendency of worsening (log-rank test, p = 0.25). However, there was a significant difference toward positive outcome for patients who received cardiac resynchronization therapy (log-rank test, p = 0.036). Using Multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard regression with the factors resynchronization and CSR, the effect of resynchronization was almost significant (p = 0.08). In conclusion, no significant change of Cheyne-Stokes prevalence can be found in our small group of modern-treated patients with CHF. Cardiac resynchronization therapy was associated with improved patient outcome.

Keywords: Cheyne-Stokes respiration, Chronic heart failure, Prognosis, Cardiac, Resynchronization therapy

Introduction

Congestive heart failure is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries. In recent years, there has been a high prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in patients with congestive heart failure [1–4]. Since the description of waxing and waning breathing pattern by Cheyne and Stokes, the occurrence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration is well recognized in congestive heart failure [5, 6]. Several investigators have shown an increased mortality in congestive heart failure combined with Cheyne-Stokes respiration [7–9]. Possibly this is based on an increased neurohumoral stress on the heart [10]. The treatment of patients with congestive heart failure has changed during the last decade as new therapeutic standards, such as beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, have been established [11, 12]. The prognosis for patients with congestive heart failure could be substantially improved by these.

Recent investigations have focused on changes in prevalence of sleep-breathing disorders. In 203 German patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, an apnea-hypopnea index cutoff of approximately 10 per hour were seen by polygraphy in 71% with a majority in obstructive sleep apnea probably due to higher body mass index [13]. In a retrospective analysis in 450 consecutive patients with congestive heart failure with an apnea-hypopnea index cutoff of approximately 10 per hour, Sin et al. found a prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing of 72% [14]. In this retrospective analysis, the prevalence of Cheyne-Stokes respiration with 33% was comparable to the German patients with 28% [13]. In contrast, the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing according to common study criteria with an apnea-hypopnea index cutoff of approximately 10 per hour in 81 patients with congestive heart failure has been approximately 50% [1]. The differences compared to the findings of Javaheri et al. are possibly the result of a higher body mass index, leading to an increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apneas. Furthermore, there was no predefined inclusion ejection fraction in Sins’ patient collective.

However, if there is a reduction of CSR and an impact of CSR on prognosis, we would expect a reduction of mortality in modern-treated congestive heart failure. This could even be forced by a new treatment option, such as cardiac resynchronization therapy, with proven influence on prevalence of CSR [15].

This study was designed to analyze the prognosis of sleep-disordered breathing, such as Cheyne-Stokes respiration, in patients suffering from modern-treated congestive heart failure.

Methods

All patients admitted to the internal medicine department at our University Hospital with heart failure were eligible if they met the following criteria: left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, and at least one episode of cardiac decompensation in the patient’s history. They all had to be in stable cardiac conditions at NYHA-classification class 2–3 with no episode of decompensation at least during the last 6 weeks. Most patients were outpatients, but also inpatients with stable cardiac conditions were eligible. All of them had to have a beta-blocker and an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin-II-antagonist as standard medication. No primary lung dysfunction with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second <65% was accepted for participants, and no myocardial infarction should have been occurred during the last 6 months. The minimum age for patients was 18 years.

All patients provided informed consent to participate in the study, which was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee at the University of Goettingen.

Polysomnography was performed in one night at the sleep laboratory of the cardiology and pneumology department during 2003–2004. No patient had a known history of sleep-disordered breathing before our investigations. To determine the stages of sleep, an electroencephalogram, a chin electromyogram, and an electrooculogram were obtained. Thoracoabdominal excursions were measured with electrodes placed on the rib cage and abdomen. Airflow was monitored with thermocouples. All polysomnographic data were collected by computer system (Alice 4, Heinen & Löwenstein, Germany). According to the criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, there had to be at least three cycles of crescendo and decrescendo change in breathing amplitude and five or more central sleep apneas or hypopneas per hour of sleep to be scored as Cheyne-Stokes respiration [16]. Furthermore, according to common study criteria, the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of >10 per hour was defined as relevant.

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistica (GmbH Software, Germany). The Mann–Whitney test was used to assess differences between patients with and those without sleep-disordered breathing, and chi-square analysis was used to analyze proportions. Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank test were performed for mortality with censored patients due to transplantation or end of follow-up time. Finally, multivariate Cox’s Proportional Hazard Regression was used to asses the effect of CSR and biventricular pacing on survival status including age, gender, and cardiac cachexia. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Fifty-seven patients were included in the study (Table 1); 24 patients had a dilated and 4 had a hypertrophic nonobstructive, whereas 29 had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. During follow-up, 12 patients died and 4 received cardiac transplantation. No patient was lost to follow-up. Five of the 9 women and 34 of the 48 men had CSR. Only three men had predominant obstructive sleep-breathing disorders.

Table 1.

Clinical data of the patients

| Variable | Patients (n = 57) | CSR (n = 39) | NCSR (n = 18) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 62.4 ± 12.8 | 61.9 ± 13.7 | 63.3 ± 10.9 | NS |

| Height (cm) | 174.8 ± 9.5 | 176.7 ± 9.5 | 170.8 ± 8.4 | <0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/ m²) | 26.4 ± 4.2 | 25.9 ± 3.7 | 27.3 ± 5.1 | NS |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 25.3 ± 6.5 | 25 ± 6 | 26 ± 7 | NS |

| LVED (mm) | 64.4 ± 8.3 | 66 ± 7 | 61 ± 10 | <0.05 |

| VO2max (ml/min/kg) | 12.4 ± 4.1 (n = 30) | 13.3 ± 4.3 (n = 20) | 10.5 ± 3.1 (n = 10) | 0.1 |

CSR patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration according to AASM-criteria, NCSR non-Cheyne-Stokes Respiration patients; NS not significant, LVED left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; VO2max = peak oxygen consumption

Beta-blocker-medication was given to all 57 patients, and 48 were treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, whereas 9 had angiotensin-II-antagonists. All patients had diuretic medications, and 17 were treated with digitalis. Twenty patients received an aldosterone antagonist. Ongoing amiodarone treatment could be evaluated in 14 patients.

According to the mentioned AASM criteria, eight patients had an AHI of <5 per hour. If common criteria from sleep investigations were used, there would have been 22 patients (44%) with an AHI of <10 per hour. Sleep-breathing disorders defined by a respiratory disturbance index (RDI) of >5 hour were seen in 74% of our patient group; 68% of all study patients had Cheyne-Stokes breathing patterns (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients during sleep

| Variable | CSR (n = 39) | NCSR (n = 18) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep time (min) | 315 ± 64 | 288 ± 100 | NS |

| Non-REM (min) | 278 ± 56 | 256 ± 79 | NS |

| REM (min) | 53 ± 26 | 46 ± 32 | NS |

| RDI (/h TST) | 26 ± 15 | 12 ± 20 | <0.00005 |

| AHI (/h) | 22 ± 13 | 10 ± 19 | <0.00005 |

| Apnea index (/h sleep) | 12 ± 13 | 7 ± 18 | <0.0005 |

| Arousal index (/h sleep) | 25 ± 13 | 31 ± 19 | NS |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 90 ± 4 | 90 ± 3 | NS |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 81 ± 7 | 84 ± 8 | NS |

CSR patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration according to AASM criteria, NCSR non-Cheyne-Stokes respiration patients, TST total sleep time, REM rapid eye movement sleep, RDI respiratory disturbance index, AHI apnea-hypopnea index, NS not significant

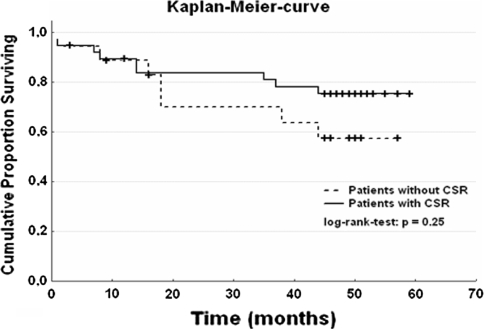

Follow-up lasted for 38 ± 18 months, and no patient was lost to follow-up. For all patients included in our analysis, the mortality tended to be lower in CSR patients than in non-CSR patients without statistical significance (log-rank test, p = 0.25; Fig. 1). Neither age nor sex showed a significant difference in both groups.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative proportion surviving for all patients. CSA = Cheyne-Stokes respiration; time = months; log-rank test, p = 0.25

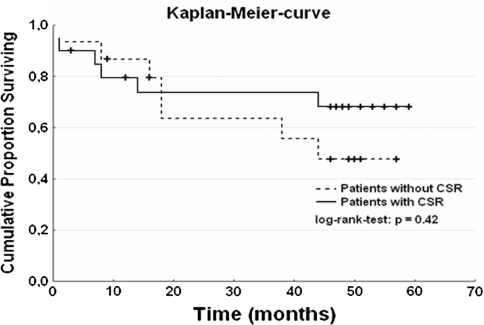

In a smaller group of 35 patients without biventricular pacing, the mortality was 6 of 15 (40%) in non-CSR and 7 of 20 (35%) in CSR patients group. Figure 2 shows the cumulative proportion that survived (log-rank test, p = 0.42).

Fig. 2.

Mortality in 35 patients without biventricular pacing. CSA = Cheyne-Stokes respiration; time = months; log-rank test, p = 0.42

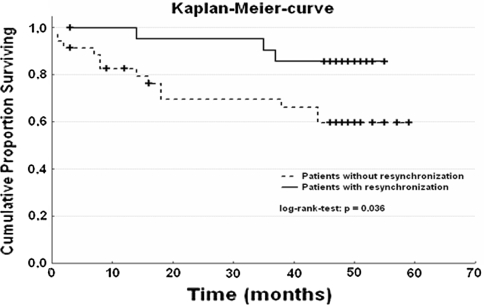

Comparison of patients with versus without cardiac resynchronization therapy revealed a significant difference in mortality (log-rank test, p = 0.036; Fig. 3). In the multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard regression, the combination of CSR and cardiac resynchronization therapy could only show a tendency for positive influence of resynchronization (hazard ratio, 0.32; 95% confidence interval, 0.09–1.16; p = 0.08).

Fig. 3.

Mortality in patients with versus without biventricular pacing. Bivent = cardiac resynchronization therapy (0 = without, 1 = with); time = months; log-rank test, p = 0.036

Discussion

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is a common sleep-breathing disorder in patients with congestive heart failure [1–4]. Previous studies also have documented poorer prognosis for this study population [7–9]. Modern medical treatment has a prognostic impact for patients with congestive heart failure [11, 12, 17, 18].

In a small study population of eight patients, Walsh and colleagues showed a reduction of apneic episodes as well as arousals and an increase of slow wave and REM sleep by treatment with captopril [19]. The prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing according to common study criteria with an apnea-hypopnea index cutoff of approximately 10 per hour in a historic collective of Javaheri et al. has been approximately 50% [1]. Still in that earlier investigation, no standard medical treatment was given as recommended by modern heart failure treatment guidelines [17]. As reported at the beginning, other investigators found a decline in prevalence by polygraphic investigation [13].

The strongest effect of modern treatment of congestive heart failure and prevalence of CSR was seen in cardiac resynchronization therapy [15]. Treatment reduction of CSR as well as an association of CSR reduction with improved sleep quality and quality of life was evident in 42 patients with heart failure by Skobel et al. [20]. A reduction in mortality for patients with congestive heart failure was described in the meta-analyses by Rivero-Ayerza et al. [21]. In our study population, this reduction in mortality during a 5-year follow-up also was shown (p < 0.04). However, no clear evidence for an association with CSR could be established from our data. Probably due to small sample size, the benefit of cardiac resynchronization showed only a tendency (p = 0.08). Furthermore, sleep investigations during follow-up for analysis of CSR reduction due to implantation of resynchronization aggregates were not obtained.

Conclusions

There appears to be no prognostic benefit for the modern medical treatment in association with CSR, although improved prognostic outcome in congestive heart failure is known. For nonpharmacologic treatments, such as cardiac resynchronization therapy, a tendency toward a beneficial influence in CSR and a significant benefit for all patients with congestive heart failure receiving resynchronization is shown. Further clinical studies have to prove this hypothesis of a significant correlation between CSR reduction and outcome in patients with congestive heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

The authors declare to have no competing interests.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, Corbett WS, Nishiyama H, Wexler L, Roselle GA. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97(21):2154–2159. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lofaso F, Verschueren P, Rande JL, Harf A, Goldenberg F. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in patients on a heart transplant waiting list. Chest. 1994;106(6):1689–1694. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findley LJ, Zwillich CW, Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke D, Tisi G, Moser KM. Cheyne-Stokes breathing during sleep in patients with left ventricular heart failure. South Med J. 1985;78(1):11–15. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreas S, Hagenah G, Moller C, Werner GS, Kreuzer H. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and prognosis in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(11):1260–1264. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00608-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheyne J. A case of apoplexy, in which the fleshy part of the heart was converted into fat. Dublin Hospital Report. 1818;2:216–223. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stokes W. The disease of the heart and the aorta. Dublin: Hodges & Smith; 1854. pp. 323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox I, McNamara SG, Wessendorf T, Willson GN, Piper AJ, Sullivan CE. Prognosis and sleep disordered breathing in heart failure. Thorax. 1998;53(Suppl 3):S33–S36. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.2008.S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanfranchi PA, Braghiroli A, Bosimini E, Mazzuero G, Colombo R, Donner CF, Giannuzzi P. Prognostic value of nocturnal Cheyne-Stokes respiration in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99(11):1435–1440. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanly PJ, Zuberi-Khokhar NS. Increased mortality associated with Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(1):272–276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreas S, Bingeli C, Mohacsi P, Luscher TF, Noll G. Nasal oxygen and muscle sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Chest. 2003;123(2):366–371. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metra M, Giubbini R, Nodari S, Boldi E, Modena MG, Dei Cas L. Differential effects of beta-blockers in patients with heart failure: a prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of the long-term effects of metoprolol versus carvedilol. Circulation. 2000;102(5):546–551. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKelvie RS, Yusuf S, Pericak D, Avezum A, Burns RJ, Probstfield J, Tsuyuki RT, White M, Rouleau J, Latini R, Maggioni A, Young J, Pogue J. Comparison of candesartan, enalapril, and their combination in congestive heart failure: randomized evaluation of strategies for left ventricular dysfunction (RESOLVD) pilot study The RESOLVD Pilot Study Investigators. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1056–1064. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz R, Blau A, Borgel J, Duchna HW, Fietze I, Koper I, Prenzel R, Schadlich S, Schmitt J, Tasci S, Andreas S. Sleep apnoea in heart failure. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(6):1201–1205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00037106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(4):1101–1106. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha AM, Skobel EC, Breithardt OA, Norra C, Markus KU, Breuer C, Hanrath P, Stellbrink C. Cardiac resynchronization therapy improves central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22(5):667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulig M, Schulte E, Willich S. Comparing methodological quality and consistency of international guidelines for the management of patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5(3):327–335. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(03)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard PA, Cheng JW, Crouch MA, Colucci VJ, Kalus JS, Spinler SA, Munger M. Drug therapy recommendations from the 2005 ACC/AHA guidelines for treatment of chronic heart failure. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(9):1607–1617. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh JT, Andrews R, Starling R, Cowley AJ, Johnston ID, Kinnear WJ. Effects of captopril and oxygen on sleep apnoea in patients with mild to moderate congestive cardiac failure. Br Heart J. 1995;73(3):237–241. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skobel EC, Sinha AM, Norra C, Randerath W, Breithardt OA, Breuer C, Hanrath P, Stellbrink C. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on sleep quality, quality of life, and symptomatic depression in patients with chronic heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Sleep Breath. 2005;9(4):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivero-Ayerza M, Theuns DA, Garcia-Garcia HM, Boersma E, Simoons M, Jordaens LJ. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on overall mortality and mode of death: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2682–2688. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]