Abstract

We reviewed long-term outcomes after open reduction by the medial approach for developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH). Forty-five hips in 43 patients with more than ten years of follow-up were assessed clinically and radiologically. The mean age at surgery was 14.0 (range 6–31) months, and the follow-up period ranged from ten to 28 years (mean 16.4 years). We compared the good (18 hips) and poor groups (27 hips) as classified by the Severin classification. The mean age at surgery was significantly older in the poor group than the good group (17.1 and 9.4 months, respectively, P < 0.001). Thirteen (29%) of 45 hips had avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head. The mean age at surgery was significantly older in the patients with AVN than without AVN (20.0 and 11.6 months, respectively, P < 0.001). Another approach, such as the wide exposure method, should be selected for DDH with increased age at operation.

Introduction

The medial approach for open reduction of developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH) was introduced by Ludloff [13] in 1908. Ludloff’s method has been described as a simple method requiring minimal dissection and tissue destruction; it allows correction of the anteroinferior tightness by releasing the tight iliopsoas tendon and the constricted antero-inferior part of the capsular ligament. Although results of this procedure have been described in many reports, the outcome remains controversial [3, 7, 9–12, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25].

Open reduction is sometimes required when the dislocation is detected after the patient has started to walk. In such cases, patients show adhesion of the postero-superior part of the capsular ligament and short external rotators because of the posterior dislocated position, and its association with weight-bearing compression.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate long-term outcomes after this approach. The relationship between age at the time of operation and radiological results were specifically evaluated.

Materials and methods

Since this is a retrospective study, our institution did not require approval from the institutional review board.

Between 1979 and 1997, 49 patients with complete hip dislocation were treated with Ludloff’s method. Of these, six patients were not followed-up after ten years because they had moved elsewhere and it was difficult to contact them. The mean age of these six patients at the time of surgery was 13.8 months (range, 6–24 months), and the mean duration of follow-up was 4.1 years (range, 1–6 years). The remaining 45 hips in 43 patients with more than ten years between surgery and our follow-up study attended clinical and radiological assessments (a recall rate of 88%). There were 36 girls and seven boys, and 24 right and 21 left hips. Two patients were affected bilaterally. The mean age at surgery was 14.0 months (range, 6–31 months), and the follow-up period ranged from ten to 28 years postoperatively (mean, 16.4 years).

Following the diagnosis of DDH, a Pavlik harness was used for the patients aged between two and seven months. In patients older than seven months of age or in whom reduction by Pavlik harness was unsuccessful, we attempted closed reduction under anaesthesia, followed by cast fixation. The indications for open reduction were as follows: the dislocated hip could not be reduced or reduction could not be maintained without a forced position (>90–100 degrees of flexion or >60 degrees of abduction) when examined under anaesthesia. Ludloff’s medial approach was used for all patients treated by open reduction during this period.

Patients were placed in supine position with the hip abducted and flexed at 90 degrees. A longitudinal skin incision was made, beginning at the origin of the adductor longus and carried distally along its tendon, and the hip was approached anteriorly to the adductor longus. The anterior part of the capsule down to the femoral neck was excised together with the hypertrophied ligamentum teres. The psoas tendon was detached near its insertion and allowed to retract proximally. The transverse ligament was divided to allow a stable reduction and the labrum was partially excised in 13 hips because concentric reduction was not obtained. Postoperatively, a hip spica cast was applied in all patients in 90–100 degrees of flexion and 70 degrees of abduction on the operated side, and in 60 degrees of abduction on the non-operated side. Extreme abduction was avoided in order to maintain blood circulation to the femoral head. After four weeks, a flexion-abduction brace was applied, and this was used for four to six months.

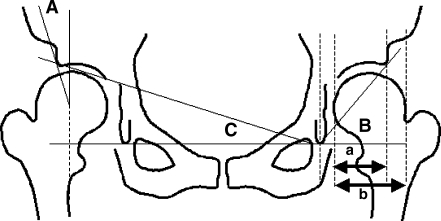

At the latest follow-up, radiological and clinical evaluations were performed using Severin [21] and McKay [17] classifications. Avascular necrosis (AVN) was classified by the criteria of Kalamchi and MacEwen [8]. To evaluate acetabular dysplasia at the time of follow-up, the centre-edge angle (CE angle) [26], acetabular head index (AHI) [6], acetabular angle [22] and acetabular roof angle [15] were calculated (Fig. 1). We defined acceptable results as those in Severin groups I and II and unacceptable results as those in Severin groups III, IV and V.

Fig. 1.

Radiographic parameters. A CE angle, AHI acetabular head index = a/b × 100, B acetabular angle, C acetabular roof angle

All radiographs were performed in the supine position. Anteroposterior radiographs were taken with a source-to-film distance of 110 cm. The patient’s feet were internally rotated with the toes at 15 ± 5 degrees to ensure that the X-ray beam was centred on the superior aspect of the pubic symphysis.

To test the reproducibility of the radiographic measurements, two authors (K.O. and H.E.) measured the CE angle, AHI, acetabular angle and acetabular roof angle in five randomly selected hips. Each hip was measured twice, with a one-week interval between measurements, and the values were then averaged. The data were analysed for intra- and interobserver variances and the coefficient of variation was calculated to be less than 5%. Therefore, we considered the reproducibility of the measurements was reasonable. To increase the accuracy and reliability of the Severin, Kalamchi and MacEwen classifications, all the roentgenograms were independently reviewed.

Differences between two means were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test. The correlation between X-ray parameters and age at operation were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (StatView software; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, California). The significance level of the hypothesis test was chosen as p < 0.05.

Results

Additional operations

Five operations that were performed later for reconstruction of the acetabulum included a Shelf operation plus derotation varus osteotomy in one hip at three years and two hips at four years, Chiari pelvic osteotomy in one hip at 11 years and a rotational acetabular osteotomy in one hip at 16 years after open reduction by medial approach.

Clinical evaluation

Two patients who had an osteotomy more than ten years after open reduction were evaluated just before the osteotomy, and three hips with osteotomy less than ten years after open reduction were excluded from clinical evaluation. Thirty-five of the remaining 39 hips were evaluated as excellent, one hip as good and three hips as fair. Two of three hips evaluated as fair were treated by osteotomy more than ten years after open reduction.

Radiological evaluation

Two patients who had an osteotomy for more than ten years after open reduction were evaluated just before the osteotomy. Severin classification was I and II in 18 hips; III, IV and V in 24 hips; and II at the final follow-up in the three hips treated by osteotomy less than ten years after open reduction (Table 1). Three patients in Severin IV and V refused to undergo additional surgery for subluxation of the femoral head and acetabular dysplasia, although it was recommended.

Table 1.

Severin classification at follow-up

| Severin class | Number of hips |

|---|---|

| I | 6 |

| II | 12 |

| III | 19 |

| IV | 3 |

| V | 2 |

| Additional operation | 3 |

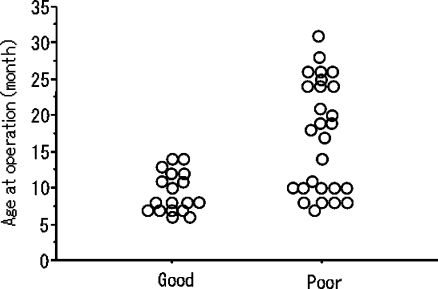

We compared the 18 hips that were classified as Severin I and II (good group) with the 27 hips from the poor group (24 classified as Severin III, IV and V at follow-up and three treated by osteotomy less than ten years after open reduction) in terms of age at surgery (Fig. 2). The mean age at surgery was 9.4 months (range, 6–14 months) for the good group and 17.1 months (range, 7–31 months) for the poor group. The mean age at the follow-up period was 16.0 years (range, 10–23 years) for the good group and 16.7 years (range, 10–28 years) for the poor group. There were significant differences in age at surgery (p < 0.001); however, there were no significant differences in the follow-up period between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

Age at operation and radiological results

Acetabular dysplasia and subluxation of the femoral head

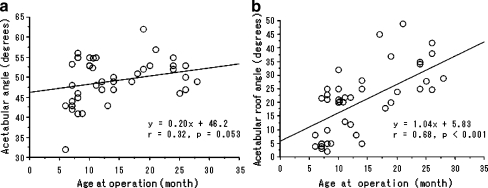

There were correlations between the age at operation and CE angle (r = –0.54, p < 0.001), and AHI (r = –0.62, p < 0.001) and acetabular roof angle (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) at follow-up. However, there was no significant correlation between age at operation and acetabular angle (r = 0.32, p = 0.053) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between age at operation and acetabular angle (a) and acetabular roof angle (b) at follow-up

Avascular necrosis

We did not include Kalamchi type I, because this does not affect radiological results at skeletal maturity. Thirteen (29%) of 45 hips had AVN of the femoral head, including ten hips in type II, one hip in type III and two hips in type IV. The mean age at surgery and during the follow-up period was 11.6 months (range, 6–28 months) and 16.2 years (range, 10–27 years), respectively, in the patients without AVN, and 20.0 months (range, 8–31 months) and 17.1 years (range, 10–28 years), respectively, in the patients with AVN. There were significant differences in age at surgery (p < 0.001), but no significant differences in the follow-up period between the two groups.

Complications

One patient had a re-dislocation diagnosed by radiograph just after the operation, and required a manual reduction and cast fixation again on the day of the operation. No major neurovascular damage or deep infections were observed in any patient.

Discussion

Some reports describe long-term results of this procedure more than ten years after surgery [11, 16, 25]. Our acceptable radiological results (40%) after open reduction by the medial approach were poorer as compared with those reported for other series. In those series, however, many patients had additional operations before the time of final evaluation. When patients treated by additional operations were classified as unacceptable, the long-term results were similar to ours. Koizumi et al. [11] reported satisfactory results in 23%, at 19 (range, 14–23) years follow-up, Matsushita et al. [16] in 34%, at 16 (range, 11–21) years follow-up and Ucar et al. [25] in 59% at 19.8 (range, 13–28) years follow-up.

Open reduction through a medial approach for DDH has been the subject of considerable controversy [3, 7, 9–12, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25]. There are several factors which are considered to influence the results.

Koizumi et al. [11] reported that poor results of this approach may come from the follow-up periods compared to other reports. In fact, the results included in our series for more than ten years follow-up were not as good as those reported for other series at less than ten years follow-up [3, 10, 14, 18].

Another factor is the age of the patients at the time of the operation. There are some reports that younger patients have good results [3, 14, 18]. In our series, the mean age at surgery was 14.0 months (range, 6–31 months), and 14 patients (31%) who were treated at more than 18 months were included.

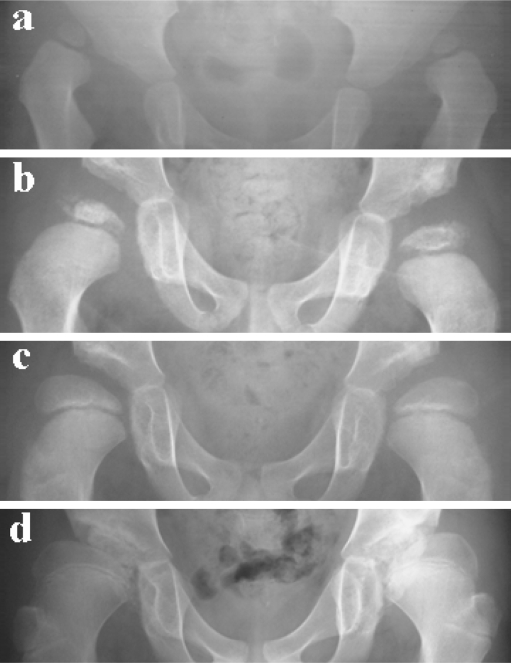

Mergen et al. [18] reported that patients between seven and 18 months of age at the time of operation had good results. Castillo et al. [3] reported that patients between five and 14 months of age at the time of operation also had good results. Mankey et al. [14] also reported that this procedure was effective in infants who were less than 24 months old. However, all studies were conducted at less than ten years average time for follow-up. On the other hand, Isiklar et al. [7] compared the radiological results for children aged 12–18 months and under 12 months at the time of surgery in a 19.6-year (range, 13–28) follow-up and reported that, although additional bone surgery is needed in a higher incidence in children 12–18 months of age, the radiological outcome is not significantly different for patients younger than 12 months. In our study, all of the patients treated at more than 17 months of age had poor results when followed-up until skeletal maturity (Figs. 2 and 4). However, improved results could be obtained by selecting patients less than 17 months of age for this approach.

Fig. 4.

a Preoperative radiograph of a 26-month-old patient with bilateral dislocations. b, c At one and three years after surgery. d At 11 years of follow-up, the radiological result was Severin group IV in both hips. The left hip was treated using the Chiari pelvic osteotomy procedure

Patients who have already started to walk with dislocation of the hip have adhesion of the posterosuperior part of the capsular ligament and short external rotators because the posterior dislocated position is associated with weight bearing compression. Matsushita et al. [16] reported good results with 84% Severin I and II in the wide exposure method for 31 hips including 15 hips (48%) aged more than 18 months at operation. They discussed that releasing the postero-superior tightness resulting from capsular adhesion to the ilium and the contracted short external rotators in a wide exposure method seems to provide a better chance of achieving an anatomically and functionally satisfactory hip.

The anterior approach has also been used for open reduction of DDH, because it provides better exposure and allows the surgeon to perform a complete capsulotomy. Several results have been reported previously after open reduction using the anterior [1, 2, 4, 5, 19, 24] and medial approaches [3, 10–12, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25] for DDH. Severin I and II observed at follow-up was 59–98% in the anterior approach [1, 2, 4, 5, 19, 24] and 45–95% in the medial approach [3, 10–12, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25], and many patients underwent additional operations prior to the final evaluation in both approaches. A prospective randomised study comparing the results of both approaches without additional operation at skeletal maturity would help determine an appropriate approach for open reduction.

A limitation of this study includes poor results observed in many patients operated at less than 17 months and because of which they could not be classified as Severin class I or II. However, no patient in this group is in Severin classes IV and V, and a correlation between X-ray parameters at follow-up and age at operation was observed in this study. Indications for this approach for DDH in patients aged less than 17 months need to be analysed further.

In this study, patients who underwent acetabular surgery less than ten years after operation were excluded from the data in order to evaluate the natural history of acetabular development after open reduction by medial approach. There are correlations between age at operation and CE angle, and AHI and acetabular roof angle at follow-up, but no significant correlation in acetabular angle (Fig. 3). Age at operation may influence the subluxation of the femoral head evaluated by CE angle, AHI and slope of the acetabulum on the weight bearing area evaluated by acetabular roof angle more strongly than the whole structure of the acetabulum evaluated by the acetabular angle at follow-up until skeletal maturity.

We used rotational acetabular osteotomy for osteoarthritis secondary to DDH, and Chiari pelvic osteotomy was selected for hips with deformed femoral heads [20]. In the future, many patients in this series will be treated by these osteotomy procedures.

We identified AVN in 13 (29%) of 45 hips after operation. An AVN rate of 0–67% has been reported after open reduction through a medial approach [3, 9–12, 14, 16, 18, 23, 25], and some describe the relationship between age at open reduction and presence of AVN at follow-up. Mergen et al. [18] reported that AVN was only observed at less than seven months and over 18 months. Castillo et al. [3] and Mankey et al. [14] reported that AVN correlated positively with increased age at surgery. In our study, age at operation was significantly higher in the patients with AVN than the patients without AVN at follow-up, and all three hips classified as Kalamchi types III and IV were operated upon at more than 17 months of age.

In conclusion, at more than ten years follow-up poor radiological results and prevalence of AVN correlated positively with increased age at open reduction by the medial approach for DDH. All the patients treated by medial approach for DDH at more than 17 months of age had unacceptable results. Another approach such as the wide exposure method should be selected for DDH in these patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Katsuro Iwasaki for assistance and advice concerning open reduction by Ludloff’s medial approach.

Footnotes

No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly to the subject of this article.

This study did not receive institutional review board approval because our institution does not require such approval for therapeutic studies.

References

- 1.Akagi S, Tanabe T, Ogawa R. Acetabular development after open reduction for developmental dislocation of the hip. 15-year follow-up of 22 hips without additional surgery. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:17–20. doi: 10.3109/17453679809002348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkeley ME, Dickson JH, Cain TE, Donovan MM. Surgical therapy for congenital dislocation of the hip in patients who are twelve to thirty-six months old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:412–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castillo R, Sherman FC. Medial adductor open reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:335–340. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordier W, Tonnis D, Kalchschmidt K, Storch KJ, Katthagen BD. Long-term results after open reduction of developmental hip dislocation by an anterior approach lateral and medial of the iliopsoas muscle. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:79–87. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhar S, Taylor JF, Jones WA, Owen R. Early open reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:175–180. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B2.2312552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyman CH, Herndon CH. Legg-Perthes disease. A method for the measurement of the rentogenographic result. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:767–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isiklar ZU, Kandemir U, Ucar DH, Tumer Y. Is concomitant bone surgery necessary at the time of open reduction in developmental dislocation of the hip in children 12–18 months old? Comparison of open reduction in patients younger than 12 months old and those 12–18 months old. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:23–27. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalamchi A, MacEwen GD. Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:876–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalamchi A, Schmidt TL, MacEwen GD. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Open reduction by the medial approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;169:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiely N, Younis U, Day JB, Meadows TM. The Ferguson medial approach for open reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip. A clinical and radiological review of 49 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:430–433. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koizumi W, Moriya H, Tsuchiya K, Takeuchi T, Kamegaya M, Akita T. Ludloff’s medial approach for open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip. A 20-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:924–929. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X78B6.6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konigsberg DE, Karol LA, Colby S, O’Brien S. Results of medial open reduction of the hip in infants with developmental dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludloff K. The open reduction of the congenital hip dislocation by an anterior incision. Am J Orthop Surg. 1913;10:438–454. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mankey MG, Arntz GT, Staheli LT. Open reduction through a medial approach for congenital dislocation of the hip. A critical review of the Ludloff approach in sixty-six hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1334–1345. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massie WK, Howorth MB. Congenital dislocation of the hip. Part I. Method of grading results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsushita T, Miyake Y, Akazawa H, Eguchi S, Takahashi Y. Open reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip: comparison of the long-term results of the wide exposure method and Ludloff’s method. J Orthop Sci. 1999;4:333–341. doi: 10.1007/s007760050113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay DW. A comparison of the innominate and the pericapsular osteotomy in the treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;98:124–132. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mergen E, Adyaman S, Omeroglu H, Erdemli B, Isiklar U. Medial approach open reduction for congenital dislocation of the hip using the Ferguson procedure. A review of 31 hips. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00395803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morcuende JA, Meyer MD, Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Long-term outcome after open reduction through an anteromedial approach for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:810–817. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okano K, Enomoto H, Osaki M, Shindo H. Outcome of rotational acetabular osteotomy for early hip osteoarthritis secondary to dysplasia related to femoral head shape: 49 hips followed for 10–17 years. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:12–17. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severin E. Contribution to the knowledge of congenital dislocation of the hip joint. Late results of closed reduction and arthrographic studies of recent cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1941;84:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharp IK. Acetabular dysplasia: the acetabular angle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sosna A, Rejholec M. Ludloff’s open reduction of the hip: long-term results. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szepesi K, Biro B, Fazekas K, Szucs G. Preliminary results of early open reduction by an anterior approach for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1995;4:171–178. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199504020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ucar DH, Isiklar ZU, Stanitski CL, Kandemir U, Tumer Y. Open reduction through a medial approach in developmental dislocation of the hip: a follow-up study to skeletal maturity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint. With special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;58:28–38. [Google Scholar]