Abstract

A prospective study is presented of 87 unstable intertrochanteric fractures treated with the proximal femoral nail anti-rotation (PFNA) with a follow-up of one year. Of the patients 76% were female. The average age was 75.3 years. The fracture was treated by closed reduction and intramedullary fixation. Pre-injury activity level was recovered in 77% of the patients. Fractures united in all patients. Mechanical failure and cut-out were not observed. A technical problem related to the mismatch of the proximal end of the nail was observed in 11 cases. Nine patients presented with thigh pain due to the redundant proximal end of the nail. The results of the PFNA were satisfactory in most elderly Chinese patients. However, the proximal end of the nail was not matched with the specific anatomy of some short elderly patients. Further modifications of the nail are necessary for the elderly Chinese population.

Introduction

The intertrochanteric femoral fracture is common in elderly patients. With societies growing continuously older, the incidence has increased markedly in recent years [7]. Due to their poor bone quality, it is very difficult to achieve and maintain a stable fixation in elderly patients [6, 7]. The aim of surgery is to achieve early mobilisation and prompt return to pre-fracture activity level. The treatment of this fracture remains a challenge to the surgeon.

Several clinical and biomechanical studies have analysed the results of different implants such as the dynamic hip screw (DHS), the Gamma nail (GN) and the proximal femoral nail (PFN). Those devices have suffered cut-out, implant breakage, femoral shaft fractures and subsequent loss of reduction in the clinical practice [1, 3, 5, 13, 14]. The proximal femoral nail anti-rotation (PFNA) system is a new device introduced by the AO/ASIF in 2003. It shares the advantage of the small distal shaft diameter with the PFN [15]. The major development is the helical blade which is supposed to compress the surrounding cancellous bone in the femoral neck and stabilise the head and neck fragment during insertion of the blade [4, 16].

To our knowledge, there are few studies on the PFNA available in the Chinese population. The purpose of this study was to report our results of the PFNA fixation in elderly Chinese patients and to observe its advantages and limitations.

Materials and methods

From January 2006 to December 2007, 125 consecutive unstable intertrochanteric fractures were treated with the PFNA (Synthes GmbH, Oberdorf, Switzerland). Ten patients were lost to follow-up. Twenty eight patients were excluded for being younger than 60 years. A total of 87 patients were available for the outcome analysis in this study. The fractures were classified as 31.A2 or 31.A3 according to the AO classification [12]. The preoperative variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Preoperative data of the patients

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 75.3 |

| Sex (male/female) | 21/66 |

| Side (left/right) | 56/31 |

| Fracture classifications | |

| A2 | 59 |

| A3 | 28 |

| Mechanisms of injury | |

| Simple fall at home | 63 |

| Traffic accident | 24 |

| ASA classificationsa | |

| 1 | 25 |

| 2 | 42 |

| 3 | 12 |

| 4 | 8 |

a American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) rating of operative risk [9]

The PFNA is available in four different sizes: the standard version (length 240 mm), a small version (length 200 mm), a very small version (length 170 mm) and a long version (length 300–420 mm). The proximal diameter is 17 mm and the diameter is 10 mm. The length of the helical blade is from 85 to 125 mm. The caput-collum-diaphysis (CCD) angle is 130 degrees. The distal part of the nail contains one oval hole for either dynamic or static locking purposes.

During surgery, all fractures were treated by closed reduction under C-arm fluoroscopy control. Spinal anaesthesia was used in all patients. All operations were performed by the same group of experienced surgeons. The surgical technique followed the manufacture’s instructions. The operative time, blood loss during surgery, fluoroscopy time, and the amount of transfused blood were recorded. The reposition of the head and neck fragment was evaluated by the Garden alignment index (GAI) and the position of the blade was evaluated by the tip apex distance (TAD) [2, 10].

In all cases antithrombotic prophylaxis was given using low molecular weight heparin (Fraxiparine), and antibiotic prophylaxis was provided (Cefazolin). The rehabilitation protocol was identical, and the patients were mobilised on the first postoperative day. Partial weight bearing as tolerated or restricted weight bearing was allowed according to the surgeon’s recommendation on the following day.

The average follow-up period was 12 months (range 9–18 months). Clinical and radiographic examinations were performed at the time of admission and at three, six and 12 months postoperatively. We noted any change in the position of the implants and the progress of fracture union.

Results

The average age of the patients was 75.3 years (range 60–93 years), of which 76% were female. According to the AO system [12], 59 fractures were type 31-A2 (67.8%) and 28 cases type 31–A3 (32.2%).

The small version PFNA (200 mm length) was the favourite and used in 50 cases (57.5% of the patients), the standard version in 16 cases (18.3%), the very small version in 14 cases (16.1%) and the long version in seven cases (8.1%). Hand reaming of the proximal femoral canal 17 mm and a 10 mm distal diameter nail was used in all fractures. The favoured length of the helical blade was 85–95 mm which was used in 77 (88%) cases. All distal locking was performed static or dynamic by means of one 4.9 mm screw.

The mean duration of surgery (skin to skin) was 53 min for the A.2 fractures and 78 min for A.3 fractures. Peroperative fluoroscopy screening took a mean time of 128 seconds for A.2 fractures and 159 seconds for A.3 fractures. The mean blood loss was 80 ml in A.2 fractures and 200 ml in A.3 fractures. Thirty-eight percent of patients required blood transfusion with a mean volume of 1.5 units in A.2 fractures and 2.5 units in A.3 fractures.

Postoperative X-rays showed a near-anatomical fracture reduction in 80% of patients. According to the Garden alignment index, 69 cases were classified as very good, ten cases good and eight cases satisfactory. Implant positioning with an average TAD of 18.9 mm (range 9–30 mm) was acceptable.

In most cases the placement of the PFNA nail was perceived as ‘‘ideal’’, in the lower half more to the centre of the femoral neck. However, in some short elderly patients, we observed 11 cases with a mismatch between the proximal end of the nail and proximal femur. For example, in nine patients, the helical blade was placed in the ideal position, but the proximal end of the nail was not completely inserted into the tip of the greater trochanter and the end remained 1–2 cm outside the bone (Fig. 1). For another, in two patients, when the proximal end of the nail was wholly inserted into the tip of the greater trochanter, the position of the helical blade was not ideally placed and the blades were placed in the lower third of the femoral neck (Fig. 2). Moreover, we noticed one case of excessive anterior bowing of the femur, and a relatively short nail was chosen during insertion of the nail (Fig. 3).

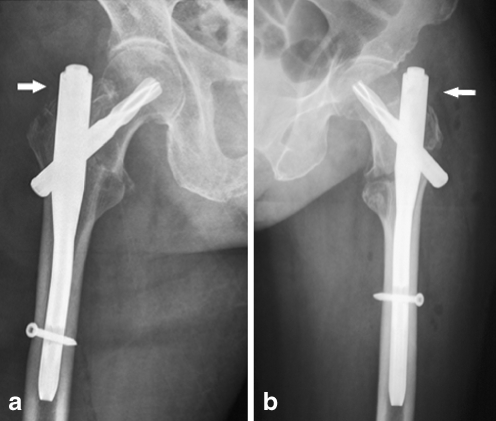

Fig. 1.

a The proximal end of the nail remained 1 cm outside the greater trochanter when a very small nail (length 170 mm) was used in a short elderly patient. b A small version nail (length 200 mm) remained 2 cm outside of the bone, the arrow indicates the redundant proximal end of the nail

Fig. 2.

The helical blades were placed in the lower third of the femoral neck, when the proximal end of the nail was wholly inserted into the tip of the greater trochanter. a A very small version nail (length 170 mm). b A small version nail (length 200 mm)

Fig. 3.

X-ray shows excessive bowing of the femoral shaft with the tip of the nail abutting the lateral wall. A small version nail was chosen to avoid passing beyond the apex of the curvature of the natural anterior bow of the femur. a Anteroposterior (AP) view. b Axial view

The mean hospital stay was 11 days. During the postoperative period, systemic complications occurred in nine patients including one pneumonia, one myocardial ischaemia, three urinary tract infections, one case of deep vein thrombosis and three cases of hypoproteinemia. The systemic and local complications are reflected in Table 2. The most frequent local complications were mismatch of proximal end of the nail and thigh pain due to the protruding proximal end of the nail. Any haematomata of the surgical wound resolved satisfactorily. Cases of superficial infection also resolved favourably once the appropriate antibiotic treatment was instituted. Mechanical failures such as bending or breaking of the implant were not seen and cut-outs were not observed.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications

| Complications | Cases |

|---|---|

| Systemic complications | |

| Pneumonia | 1 |

| Myocardial | 1 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 |

| Hypoproteinemia | 3 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 |

| Local complications | |

| Haematoma | 5 |

| Superficial infection | 3 |

| Shaft fractures at the nail tip | 1 |

| Mismatch of proximal end of the nail | 11 |

| Thigh pain (due to proximal end of the nail) | 9 |

| Limb shortening within 2 cm | 1 |

At the time of final follow-up, 67 patients (77%) were fully weight-bearing and recovered their pre-injury activity levels, ten (11.5%) walked with two crutches and two (2.3%) used a wheelchair; fracture union occurred in all patients. Eight patients (9.2%) died during the follow-up period due to causes unrelated to the fracture.

Discussion

In this study, although follow-up times were not adequate to obtain long-term outcomes, the 12-month results of the PFNA fixations were satisfactory. The results showed that the PFNA provided reliable fixation for the elderly Chinese patients. The operative procedure for the PFNA was easily performed, thus reducing the blood loss and operative time. In our study the intraoperative variables and the systemic complications were similar to those encountered by other authors [15, 16]. Most patients (77%) recovered their pre-injury walking ability, and fracture healing occurred in all patients at the final follow-up. There were few postoperative complications associated with mechanical failure. No cases of implant breakage and fatigue were seen during the follow-up period. The helical blade effectively decreased the incidence of cut-out.

In our series, 11 cases of mismatch between the proximal end of the nail and proximal femur were encountered in the short elderly patients. As the height in a Chinese population on average is less than that of Europeans and Americans, the proximal femoral length and femoral neck diameter are relatively shorter [11]. When the PFNA was used in short elderly Chinese patients, the length of the proximal end of the nail proved to be too long, resulting in inappropriate placement of the spiral blade or redundancy of the proximal end of the nail. Therefore, when the patients started to walk or mobilise, the redundant proximal end of the nail irritated the soft tissue of the hip resulting in the thigh pain and discomfort. This kind of mismatch has rarely been reported in recent literature.

Leung et al. [11] reported the geometric mismatch between the gamma nail and the Chinese femur. A relatively shorter femur and excessive anterior bowing in the older Chinese population lead to the tip of the standard nail or even the shortest nail usually passing beyond the most convex part of the anterior bow. Therefore, Leung et al. suggested that the distal tip of the nail should not pass beyond the apex of the curvature of the natural anterior bow of the femur. Jin et al. [8] considered the long nail with a curvature could be useful when the mismatch between PFNA nail and medullary canal caused difficulty in nailing of the pertrochanteric fractures. In this study, we also noticed this phenomenon of the excessive anterior bowing in the older Chinese population. In order not to pass beyond the apex of the curvature of the natural anterior bow of the femur, a relatively shorter nail should be chosen at the time of insertion of the nail.

Baumgaertner et al. [2] described a lower complication rate for implant tips placed close to the subchondral bone of the femural head and recommended bringing the tip of the helical blade up to 5 mm distance from the subchondral area. Brunner et al. [4] reported three cases of postoperative perforation of the helical blade through the femoral head into the hip joint, and in cases of severe osteoporosis they believed that prereaming of the blade 5 mm below the joint should not be performed. When using the PFNA in osteopoenic patients it is advisable to use a blade that is shorter than recommended to avoid collapse with subsequent head perforation. Although our results differed from those of Baumgaertner et al. [2], a shorter helical blade worked better in the elderly Chinese patients. We considered that it was safe to bring the tip of the helical blade up to within 10 mm of the subchondral area as recommended in the operation guidelines.

In conclusion, the results of the PFNA were satisfactory in most elderly Chinese patients. However, the proximal end of the nail is not matched with the specific anatomy of some short elderly patients. Further modifications of the nail are necessary for the elderly Chinese population.

Acknowledgments

Statement on conflict of interest The authors have not received nor will receive benefits from any source for this study.

References

- 1.Andreas A, Norbert S, Martin B, et al. Complications after intramedullary stabilization of proximal femur fractures: a retrospective analysis of 178 patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2007;33:262–267. doi: 10.1007/s00068-007-6010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM, et al. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995;78:1058–1064. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatrix H, Andre G. Complications following the treatment of trochanteric fractures with the gamma nail. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:692–698. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner A, Jockel JA, Babst R. The PFNA proximal femur nail in treatment of unstable proximal femur fractures—3 cases of postoperative perforation of the helical blade into the hip joint. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:731–736. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181893b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingo L, Cecilia D, Herrera A, et al. Trochanteric fractures treated with a proximal femoral nail. Int Orthop. 2001;25:298–301. doi: 10.1007/s002640100275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans PJ, Mcgory BJ. Fractures of the proximal femur. Hospital Physician. 2002;38(4):30–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felix B, Henry Z, Christoph L, et al. Treatment strategies for proximal femur fractures in osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:S93–S102. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin HH, Jong KO, Sang HH, et al. Mismatch between PFNa and medullary canal causing difficulty in nailing of the pertrochanteric fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(12):1443–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0736-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keats AS. ASA classification of physical status: a recapitulation. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:233–236. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenich A, May E, Rüter A, et al. First results with the trochanter fixation nail (TFN): a report on 120 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126:706–712. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung KS, Procter P, Robioneck B, et al. Geometric mismatch of the Gamma nail to the Chinese femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;323:42–48. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker J. The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. Berlin: Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papasimos S, Koutsojannis CM, Panagopoulos A. A randomised comparison of AMBI, TGN and PFN for treatment of unstable trochanteric fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:462–468. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schipper IB, Steyerberg EW, Castelein RM, et al. Treatment of unstable trochanteric fractures: Randomised comparison of the gamma nail and the proximal femoral nail. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004;86:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmermacher RKJ, Bosch AM, Werken C. The AO/ASIF proximal femoral nail (PFN): a new device for the treatment of unstable proximal fractures. Injury. 1999;30:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmermacher RKJ, Ljungqvist J, Bail H, et al. The new proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) in daily practice: results of a multicentre clinical study. Injury. 2008;39:932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]