Abstract

We conducted an up-to-date meta-analysis of 20 eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) containing 3,109 patients to compare arthroplasty with internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures regarding the effect on clinical outcomes. Computerised databases were searched for RCTs published from January 1979 to May 2008. The results showed that compared to internal fixation arthroplasty led to significantly fewer surgical complications at two and five years postoperatively and reduced the incidence of reoperation at one, two and five years postoperatively (P < 0.001). However, arthroplasty was associated with greater risk of deep wound infection, longer operating time and greater operative blood loss. Arthroplasty substantially increased the risk of reoperation following deep wound infection (P < 0.05). For mortality, there was increased postoperative risk for arthroplasty compared with internal fixation, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at the different follow-up times. For pain at one year postoperatively, the result showed no statistically significant difference.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00264-009-0763-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Introduction

Displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures are very common orthopaedic injuries in elderly patients [7] and account for approximately 50% of hip fractures [13, 24]. As the geriatric population and average life expectancy are increasing, the prevalence of these fractures is steadily increasing throughout the world. When femoral neck fractures occur, they cause considerable disability, increased dependence and death for the injured patient and have provided major challenges for health care systems.

Operative alternatives for displaced femoral neck fractures differ greatly throughout the world, but mainly include prosthetic replacement (arthroplasty) and internal fixation (IF). Options for arthroplasty include unipolar hemiarthroplasty, bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. Options for internal fixation include multiple screws, a compression screw and side plate or an intramedullary hip screw device. However, whether arthroplasty or IF is more appropriate for displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients is still being debated [12, 25, 26]. IF preserves the femoral head; in addition, it has shorter operative time, less blood loss and operative trauma, while arthroplasty might increase operative mortality [14, 16, 31]. However, some authors favour arthroplasty because the replacement of the femoral neck can decrease the rate of revision surgery and the complications related to healing of the fracture [2, 5, 17, 23].

A number of clinical studies comparing arthroplasty with IF have been undertaken. They include observational studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews. The first RCT was performed by Söreide et al. [26] in 1979, followed by the studies of Sikorski et al. [23] and Skinner et al. [25]. Most of these RCTs are relatively small. A meta-analysis by Lu-Yao et al. [14] is mainly based on observational studies. There are a few RCTs collected in two other systematic reviews conducted by Bhandari et al. [1] and Rogmark et al. [22].

These studies have mainly focused on the short-term mortality, rates of reoperation and surgical complications and did not refer to the general medical complications, such as thromboembolic complications, pressure sores and cerebrovascular accidents, although these are equally important. In this paper we address these issues by conducting an up-to-date meta-analysis of RCTs published up to May 2008. The purpose is to evaluate the clinical outcomes comparing arthroplasty with IF, including the long-term mortality, revision surgery rates and surgical complications, as well as general medical complications. It is hoped that the findings will improve our understanding of the treatment for displaced femoral neck fracture in elderly patients.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

We included only studies meeting the following criteria: randomised controlled trails comparing IF with arthroplasty; included patients aged 60 years or over with an acute displaced fracture of the femoral neck (Garden stage III or IV fractures) [28]; reported clinical outcomes, such as mortality, the rates of general complications, fracture-related complications and revision surgery. No language restriction was applied. We also allowed “quasi-randomised” trials in which patients were allocated according to known characteristics such as their date of birth, hospital chart number or day of presentation. All studies included patients having surgery for the first time.

Publication selection

A literature search of four computerised databases (PubMed, EMBASE, BIOSIS and Ovid) from January 1979 to May 2008 was carried out. Specific search terms (femoral neck fractures, IF, prosthetic replacement or arthroplasty, elderly or aged) were used. Titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two of us; all relevant articles were then retrieved and read to determine their eligibility. We also examined the reference lists of eligible studies for potentially relevant reports and searched for reference in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The searches were supplemented with manual searches of bibliographies of the published articles and major orthopaedic textbooks and personal files.

Data extraction

All relevant data from papers that met the initial inclusion criteria were extracted independently by two of the authors (JW and PZ). Disagreement was resolved by discussion. We sought the following summary data from each study: (1) information on general characteristics of participants that are listed in Table 1; (2) operative details (length of surgery, operative blood loss, blood transfusion units); (3) the postoperative general medical complications that are listed in Table 2; (4) other complications resulting directly from the surgical procedure, which we refer to as “surgical complications” and which include: non-union or early redisplacement, avascular necrosis, fracture below or around the implant, dislocation, loosening of the prosthetic, acetabular erosion, fracture below or around the implant and other surgical complications; (5) hip function (pain, walking and movement) and the health-related quality of life.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 20 studies used in the meta-analysis

| Authors | Year | Country | Follow-up (months) | Interventions | Number of patients | Age (years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasty | IF | Arthroplasty | IF | |||||

| Blomfeldt et al. [2] | 2005 | Sweden | 48 | THR | Two cannulated screws | 49 | 53 | ≥70 |

| Blomfeldt et al. [3] | 2005 | Sweden | 24 | Hemi- | Two cannulated screws | 30 | 30 | >70 |

| Davison et al. [4] | 2001 | UK | 60 | Hemi- | ‘Ambi’ compression hip screw and 2-hole plate | 187 | 93 | 65–79 |

| Frihagen et al. [5] | 2007 | Norway | 24 | Hemi- | Two parallel cannulated screws | 110 | 112 | ≥60 |

| Jensen et al. [8] | 1984 | Denmark | 24 | Hemi- | 4 AO screws | 52 | 50 | >70 |

| Johansson et al. [9] | 2000 | Sweden | 24 | TRH | 2 parallel Olmed screws | 68 | 78 | ≥75 |

| Jonsson et al. [10] | 1996 | Sweden | 24 | TRH | Hansson hook pins | 23 | 24 | 67–89 |

| Keating et al. [11] | 2006 | UK | 24 | Hemi- & TRH | Cancellous screws or sliding hip screw | 180 | 118 | ≥60 |

| Neander et al. [15] | 1997 | Sweden | 18 | TRH | 2 parallel Olmed screws | 10 | 10 | 79–94 |

| Parker et al. [16] | 2002 | UK | 12 | Hemi- | 3 AO screws | 229 | 226 | >70 |

| Puolakka et al. [18] | 2001 | Finland | 24 | Hemi- | 3 Ullevaal screws | 15 | 16 | >75 |

| Ravikumar and Marsh [19] | 2000 | UK | 156 | Hemi- & TRH | Richards compression screw and plate | 180 | 91 | >65 |

| Rödén et al. [20] | 2003 | Sweden | 60 | Hemi- | 2 von Bahr screws | 47 | 53 | >70 |

| Rogmark et al. [21] | 2002 | Sweden | 24 | Hemi- & TRH | Hansson hook pins or Olmed screws | 192 | 217 | ≥70 |

| Sikorski and Barrington [23] | 1981 | UK | 12 | Hemi- | Garden screws | 114 | 76 | ≥70 |

| Söreide et al. [26] | 1979 | Norway | 12 | Hemi- | Von Bahr screws | 53 | 51 | ≥67 |

| Svenningsen et al. [27] | 1985 | Norway | 36 | Hemi- | Compression screw versus McLaughlin nail plate | 59 | 110 | >70 |

| Tidermark et al. [29] | 2003 | Sweden | 24 | THR | Two cannulated screws | 49 | 53 | ≥70 |

| van Dortmont et al. [30] | 2000 | Netherlands | 24 | Hemi- | 3 AO/ASIF screws | 29 | 31 | >70 |

| van Vugt et al. [31] | 1993 | Netherlands | 36 | Hemi- | Dynamic hip screw | 22 | 21 | 71–80 |

IF internal fixation, THR total hip replacement, Hemi- hemiarthroplasty

Table 2.

The incidence of general medical complications with arthroplasty and internal fixation

| General medical complication | Studies | Participants | RR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasty | IF | |||||

| Superficial wound infection | 14 | 30/1,038 | 23/948 | 1.17 (0.72–1.90) | 0.52 | 0.37 |

| Deep wound infection | 15 | 31/1,487 | 15/1,334 | 1.82 (1.03–3.21) | 0.04 | 0.74 |

| Pneumonia | 5 | 27/475 | 25/528 | 1.18 (0.71–1.97) | 0.52 | 0.25 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 9 | 14/780 | 13/781 | 1.01 (0.51–2.00) | 0.98 | 0.65 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 9 | 10/780 | 13/781 | 0.77 (0.35–1.68) | 0.51 | 0.79 |

| Thromboembolic complications combined | 13 | 30/1,076 | 33/1,101 | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 0.60 | 0.61 |

| Cardiac failure | 4 | 17/512 | 16/545 | 1.14 (0.59–2.20) | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 | 10/559 | 4/509 | 1.73 (0.66–4.53) | 0.26 | 0.50 |

| Stroke | 9 | 16/812 | 13/833 | 1.17 (0.59–2.33) | 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Gastrointestinal complications | 3 | 13/349 | 7/354 | 1.84 (0.77–4.41) | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Pressure sores | 7 | 13/679 | 15/704 | 0.90 (0.45–1.80) | 0.76 | 0.61 |

RR relative risk, 95% CI 95% confidence interval, P significance of the statistical test

Statistical analysis

We used a fixed effects model in the meta-analysis unless there was significant heterogeneity (P < 0.01) between studies, when we used the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird. We tested for heterogeneity using the Breslow-Day test; we report relative risks (RR) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each clinical outcome and standardised mean difference (SMD) or weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous variables. Subgroup analyses were carried out according to the different types of internal fixation—whether multiple screws or a compression screw and side plate—to assess the clinical outcomes between arthroplasty and various internal fixation devices. Publication bias was tested by funnel plots. The meta-analysis was performed by RevMan4.2 software; for outcome measures, a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

There were 180 potentially relevant papers. By screening the title, reading the abstract and the entire article, 20 published studies [2–5, 8–11, 15, 16, 18–21, 23, 26, 27, 29–31] met all the inclusion criteria and proved eligible for this investigation. They included a total of 3,109 patients. Table 1 provides a summary of the studies, author, year of publication, their location, sample size, follow-up period, interventions and age of patients. Internal fixation was mostly performed with multiple screws, but in five studies [4, 11, 19, 27, 31] a compression screw and plate were used.

Complications

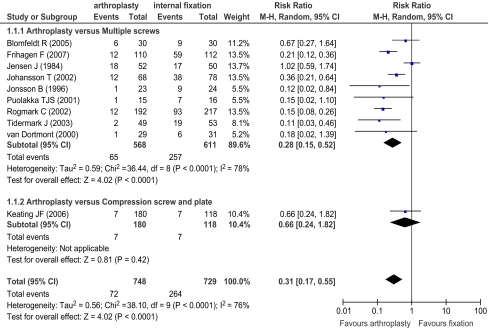

Ten of the eligible studies, including a total of 1,477 patients, reported information on surgical complications at two years postoperatively. The results are presented in Fig. 1. The study rates ranged from 3.5 to 34.6% in the arthroplasty groups and from 5.9 to 52.7% in the IF groups. Five of the ten studies were not significant (P > 0.05), but all relative risks were below 1. The pooled result showed a reduced risk of surgical complications with arthroplasty in comparison with IF (RR = 0.31), which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). There was a lower risk of surgical complications for arthroplasty compared with multiple screws (RR = 0.28, P < 0.001) and a similar reduction for a compression screw and plate, although the result was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Surgical complications reported postoperatively after 2 years follow-up

Surgical complications at five years postoperatively were reported in only two studies, including a total of 380 patients. There was, however, a statistically significant difference between arthroplasty and IF (RR = 0.18, P < 0.001).

Table 2 shows that for all general medical complications except for deep wound infection there were no statistically significant differences between arthroplasty and IF (P > 0.05), although generally arthroplasty marginally increased the risk. Fifteen trials reported the number of patients with deep wound infection. For arthroplasty, there were 31 of 1,487 patients with deep wound infection and for IF, 15 of 1,334 patients. Arthroplasty substantially increased the risk (RR = 1.82, P = 0.04) of deep wound infection, and the results were consistent in all studies included.

Finally, considering pain as a complication, only five studies, with 750 patients, reported detailed data on residual pain at one year postoperatively. There was no statistically significant difference between the IF and arthroplasty groups (P > 0.05).

Reoperation

Table 3 shows results of the necessity for reoperation at different time points. There was a statistically significant difference between arthroplasty and IF (P < 0.001). Generally, taking the inverse relative risk, patients having IF are about four times more likely to need a second operation. Subgroup analysis also showed that, in comparison with all types of internal fixation, arthroplasty substantially reduced the risk of reoperation. As for reoperation following deep wound infection, 12 studies provided the number of patients receiving reoperations. There were 20 of 1,329 patients in the arthroplasty group requiring reoperation and five of 1,121 patients in the IF group. The pooling of data showed that arthroplasty substantially increased the risk of reoperation following deep wound infection (RR = 2.40, P = 0.03).

Table 3.

Reoperations at 1, 2 and 5 years postoperatively with arthroplasty and internal fixation

| Reoperation | Studies | Events | RR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasty | IF | |||||

| 1 year | 3 | 15/177 | 39/137 | 0.29 (0.17–0.49) | <0.001 | 0.41 |

| 2 years | 10 | 68/748 | 316/729 | 0.22 (0.17–0.28) | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| 5 years | 2 | 16/234 | 62/146 | 0.20 (0.12–0.32) | <0.001 | 0.22 |

Mortality

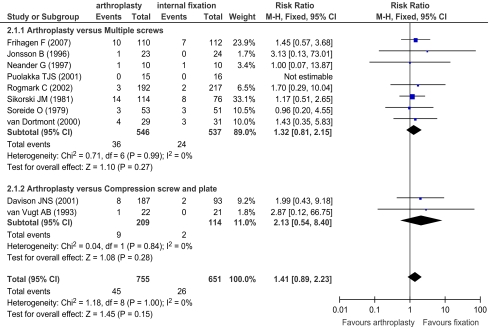

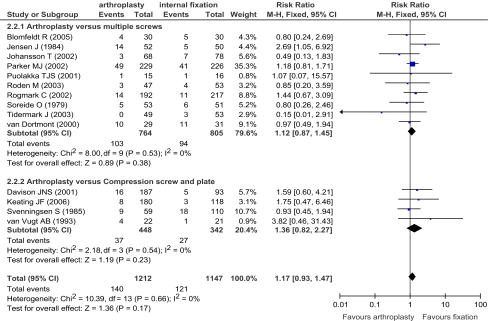

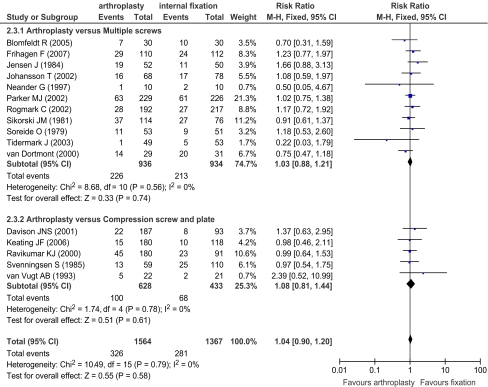

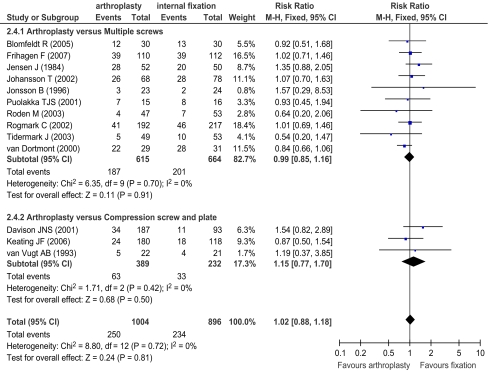

Figure 2 shows a forest plot of mortality rates at one month postoperatively in the ten studies in which it was reported, including a total of 1,406 patients. Overall there was greater mortality by arthroplasty (RR = 1.41), though not statistically significant. Figure 3 shows a corresponding plot for mortality at 4–6 months postoperatively in the 14 studies in which it was reported involving 2,359 patients. It shows only a small increase in mortality due to arthroplasty (RR = 1.17). Extending the period of follow-up, Figs. 4 and 5 show mortality at one and two years, respectively. In neither case was there any difference in mortality rates. The mortality at three years postoperatively was reported just in four of the selected studies, but again showed no difference. Subgroup analysis also showed that there was no significant difference in comparison of arthroplasty with either multiple screws or a compression screw and plate at different time points. In summary, the results show that initially postoperative mortality is greater for arthroplasty, but in time there are no differences.

Fig. 2.

Mortality at 1 month postoperatively reported in ten studies

Fig. 3.

Mortality at 4–6 months postoperatively reported in 14 studies

Fig. 4.

Mortality at 1 year postoperatively reported in 16 studies

Fig. 5.

Mortality at 2 years postoperatively reported in 13 studies

Operative details

Table 4 summarises the findings: operation time, the degree of blood loss and the mean number of blood transfusion units required. Arthroplasty took about 30 min longer than IF, involved greater blood loss and required more units of blood transfusion.

Table 4.

Summary of three outcomes directly related to the nature of the operations

| Outcome | Studies | Participants | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasty | IF | |||||

| Operation time (min) | 8 | 680 | 634 | 34.86 (20.80–48.92) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 7 | 500 | 516 | 311.22 (199.85–422.59) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Mean units blood transfused | 2 | 270 | 276 | 0.57 (0.04–1.10) | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Discussion

Our meta-analysis has provided evidence that in comparison with IF, arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures has lower long-term risks of surgical complications at two and five years postoperatively and also reduces the incidence of reoperation at one, two and five years postoperatively. However, arthroplasty was associated with greater risk of general medical complications, in particular of deep wound infection, and substantially increased the risk of reoperation following deep wound infection. Arthroplasty was also associated with a longer operating time and greater operative blood loss. As to mortality, there was increased postoperative risk for arthroplasty compared with IF, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at different follow-up times. Arthroplasty and IF do not differ with regard to their impact on postoperative pain.

Meta-analysis of RCTs is generally considered to provide the strongest evidence [6] of clinical interventions and has more advantages than observational research studies and single randomised trials. Observational research studies, regardless of the integrity and care with which they are conducted, are open to bias and single randomised trials are often limited by relatively small sample sizes and resulting imprecision in the estimates of treatment effects. In our meta-analysis, according to explicit inclusion criteria, we included only 20 eligible RCTs and believe our results to be valid. The number of studies is more than that of previous similar reviews [1, 22]. Nevertheless, there are limitations to meta-analysis. One is that of publication bias. Insofar as funnel plots could show, our study is not subject to this bias. Another issue is study heterogeneity, both in the nature of the studies themselves and in the statistical heterogeneity of individual relative risks. Concerning the latter, there was no apparent heterogeneity. There were though differences in the protocols of the studies identified. For example, although all studies included elderly patients, there were differences in age ranges (Table 1) in the studies included. It is possible that there may be effect modification by age, but we could not determine this from the data available.

According to the best estimates from our meta-analysis, arthroplasty significantly reduced the risk of reoperation. The relative risk for reoperation at one, two and five years was 0.29, 0.22 and 0.20, respectively. Or, put another way, IF has about a fourfold increased risk. As the follow-up period of most of the studies was one to three years, the overall reoperation rate is lower than would occur in clinical practice. This may be particularly relevant for the long-term revision rate of the arthroplasties, which was not well documented. Another reason is that our meta-analysis only pooled the data on the number of patients who underwent secondary operations from selected studies. In fact, a number of these patients would have more than one secondary operation; for example, a patient initially had an IF device removed and later an arthroplasty was performed. In addition, dislocation of an arthroplasty may have occurred more than once in some patients, particularly for those with arthroplasty. The number of times that recurrent dislocation occurred was often not reported. This meant that we were not able to present results for the total number of reoperations for the different treatment methods. Ravikumar et al. [19], with the longest follow-up period of 13 years, showed a reoperation rate of only 7% after arthroplasty. This reduced long-term risk might be due to the higher mortality in elder femoral neck fracture patients aged 60 years or over.

As to mortality rate, our pooled results show that there was an increased risk for arthroplasty compared with IF, but there was essentially no longer term difference between groups at four to six months, one, two and three years postoperatively. In the studies of Jensen et al. [8] and Parker et al. [16], there was a trend to a lower early mortality for those treated by IF. In addition, the majority of studies did not undertake an intention to treat analysis and might bias the outcome of mortality in favour of arthroplasty; for example, Rogmark et al. [21] stated that ten patients were excluded after randomisation as they were considered unfit for arthroplasty. The outcomes for these patients should have been included within the group to which they were randomised, but were in fact excluded from the analysis. This means that potentially sicker patients were removed from the arthroplasty group.

The important final outcome measure of pain was poorly reported or not even mentioned in many studies. In our study, only five studies with 750 patients covered the detailed data on residual pain at one year postoperatively; the pooled result of these data showed no statistically significant difference. Most of the RCTs found less pain and better function after cemented arthroplasty than after IF. The explanation may be that during the time it takes to heal a fracture treated with IF pain prevents the patient from successful rehabilitation. In contrast, cemented arthroplasty gives skeletal stability immediately and allows patients to move more freely.

We examined three outcomes directly related to the nature of the operations: its length, the degree of blood loss and the mean number of blood transfusion units required. In total, there were eight studies that reported length of the operation in minutes, seven studies that reported intraoperative blood loss in ml and only two studies reporting mean units blood transfused. The pooled results showed that arthroplasty took about 30 minutes longer than IF, involved greater blood loss and required more units of blood transfusion.

In summary, we believe the analysis offers useful conclusions, comparing arthroplasty with IF in displaced femoral neck fractures, and shows that for surgical complications as well as for reoperation with open surgery there is an advantage to performing arthroplasty. One concern has been increased mortality at each different follow-up time postoperatively, but there was no significant difference in both groups. Arthroplasty increased risk of deep wound infection. For better health, we need to more carefully consider issues of long-term outcomes and intraoperative and preoperative factors and report them in a reliable, consistent and standardised manner.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 24 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 24 KB)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Projects in the National Science & Technology Pillar Program in the Eleventh Five-year Plan Period in the People’s Republic of China (Grant No.: 2007BAI04B00). We would like to thank the authors who provided additional data and the staff for help with the literature search in Peking University Health Science Library, and we thank Feng Wang, Ph.D. for his support.

References

- 1.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P, III, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, Nork S, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1673–1681. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Söderqvist A, Tidermark J. Comparison of internal fixation with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures. Randomized, controlled trial performed at four years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1680–1688. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Söderqvist A, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:523–529. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison JN, Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Ward G, Jagger C, Harper WM, Gregg PJ. Treatment for displaced intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. A prospective, randomised trial in patients aged 65 to 79 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:206–212. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen JE. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:1251–1254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39399.456551.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. The basics of evidence based medicine. London: BMJ Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedlund R, Lindgren U, Ahlbom A. Age- and sex-specific incidence of femoral neck and trochanteric fractures. An analysis based on 20,538 fractures in Stockholm County, Sweden, 1972–1981. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;222:132–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen J, Rasmussen T, Christensen S, Holm-Moller S, Lauritzen J. Internal fixation or prosthetic replacement in fresh femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:712. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson T, Jacobsson SA, Ivarsson I, Knutsson A, Wahlström O. Internal fixation versus total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomized study of 100 hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:597–602. doi: 10.1080/000164700317362235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson B, Sernbo I, Carlsson A, Fredin H, Johnell O. Social function after cervical hip fracture. A comparison of hook-pins and total hip replacement in 47 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:431–434. doi: 10.3109/17453679608996662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keating JF, Grant A, Masson M, Scott NW, Forbes JF, on behalf of the Scottish Orthopaedic Trials Randomized comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. Treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fractures in healthy older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:249–260. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan RJ, MacDowell A, Crossman P, Datta A, Jallali N, Arch BN, Keene GS. Cemented or uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures. Int Orthop. 2002;26:229–232. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lofthus CM, Osnes EK, Falch JA, Kaastad TS, Kristiansen IS, Nordsletten L, Stensvold I, Meyer HE. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Oslo, Norway. Bone. 2001;29:413–418. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, Wennberg JE. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:15–25. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neander G, Adolphson P, Sivers K, Dahlborn M, Dalén N. Bone and muscle mass after femoral neck fracture. A controlled quantitative computed tomography study of osteosynthesis versus primary total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116:470–474. doi: 10.1007/BF00387579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MJ, Khan RJ, Crawford J, Pryor GA. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised trial of 455 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:1150–1155. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B8.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partanen J, Jalovaara P. Functional comparison between uncemented Austin-Moore hemiarthroplasty and osteosynthesis with three screws in displaced femoral neck fractures—a matched-pair study of 168 patients. Int Orthop. 2004;28:28–31. doi: 10.1007/s00264-003-0517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puolakka TJ, Laine HJ, Tarvainen T, Aho H. Thompson hemiarthroplasty is superior to Ullevaal screws in treating displaced femoral neck fractures in patients over 75 years. A prospective randomized study with two-year follow-up. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2001;90:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur—13 year results of a prospective randomised study. Injury. 2000;31:793–797. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00125-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rödén M, Schön M, Fredin H. Treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomized minimum 5-year follow-up study of screws and bipolar hemiprostheses in 100 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:42–44. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogmark C, Carlsson A, Johnell O, Sernbo I. A prospective randomised trial of internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the neck of the femur. Functional outcome for 450 patients at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:183–188. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B2.11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogmark C, Johnell O. Primary arthroplasty is better than internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies with 2,289 patients. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:359–367. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikorski JM, Barrington R. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty for the displaced subcapital fracture of the femur. A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:357–361. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B3.7263746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer BR, McLauchlan GJ, Robinson CM, Christie J. Epidemiology of fractures in 15,000 adults: the influence of age and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:243–248. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B2.7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner P, Riley D, Ellery J, Beaumont A, Coumine R, Shafighian B. Displaced subcapital fractures of the femur: a prospective randomized comparison of internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty and total hip replacement. Injury. 1989;20:291–293. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Söreide O, Mölster A, Raugstad TS. Internal fixation versus primary prosthetic replacement in acute femoral neck fractures: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Br J Surg. 1979;66:56–60. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800660118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svenningsen S, Benum P, Nesse O, Furset OI. Femoral neck fractures in the elderly. A comparison of 3 therapeutic methods (in Norwegian) Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:492–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomsen NO, Jensen CM, Skovgaard N, Pedersen MS, Pallesen P, Soe-Nielsen NH, Rosenklint A. Observer variation in the radiographic classification of fractures of the neck of the femur using Garden’s system. Int Orthop. 1996;20:326–329. doi: 10.1007/s002640050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Söderqvist A, Törnkvist H. Internal fixation compared with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly. A randomised, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:380–388. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B3.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dortmont LM, Douw CM, Breukelen AM, Laurens DR, Mulder PG, Wereldsma JC, Vugt AB. Cannulated screws versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures in demented patients. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 2000;89:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vugt AB, Oosterwijk WM, Goris RJ. Osteosynthesis versus endoprosthesis in the treatment of unstable intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1993;113:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00440593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 24 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 30 KB)

(DOC 24 KB)