Abstract

Resection arthroplasty—known as the Keller procedure—is used for the treatment of severe hallux rigidus. As a modification of this procedure, resection arthroplasty is combined with cheilectomy and interposition of the dorsal capsule and extensor hallucis brevis tendon, which are then sutured to the flexor hallucis brevis tendon on the plantar side of the joint (capsular interposition arthroplasty). In this study the clinical and radiological outcome of 22 feet treated by interposition arthroplasty were investigated and compared with those of 30 feet on which the Keller procedure was performed. The mean follow-up period was 15 months. No statistically significant difference was found between either group concerning patient satisfaction, clinical outcome and increase in range of motion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. At follow-up, patients who had undergone interposition arthroplasty did not show statistically significantly better American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) forefoot scores than those of the Keller procedure group. A high rate of osteonecrosis of the first metatarsal head was found in both groups. These radiological findings did not correlate with the clinical outcome at follow-up. In conclusion, no significant benefit in clinical or radiological outcome was found for capsular interposition arthroplasty compared with the Keller procedure.

Résumé

La résection arthroplastique de la base de P1 technique de Keller a été utilisée pour le traitement des hallux rigidus sévères. Une modification de cette technique avec chulectomie et interposition capsulaire par le tendon de l’extenseur suturé au tendon du fléchisseur a également été utilisée. 22 patients bénéficiant d’une interposition ont été comparés à 30 patients ayant bénéficié d’une intervention de Keller simple. Le suivi moyen a été de 15 mois. Il n’y a pas de différence significative entre les deux groupes en terme de satisfaction, d’évolution clinique et de mobilité de l’articulation. A la fin du suivi, les patients ayant bénéficié d’une interposition ne présentent pas un score de l’AOFAS supérieur au groupe résection simple de type Keller. Un taux important d’ostéonécrose de la première tête métatarsienne a été retrouvée dans les deux groupes. Cette découverte radiologique n’influence pas le résultat final et ne lui est pas corrélée. En conclusion, il n’y a pas de bénéfice à réaliser une interposition capsulaire dans la technique de type Keller.

Introduction

For surgical treatment of hallux rigidus many different procedures have been described, including resection arthroplasty [3, 13], tendon interposition arthroplasty [1, 4], cheilectomy [11, 16], osteotomy [19], arthrodesis [2, 15] and implant arthroplasty [5]. Resection arthroplasty (‘Keller procedure’) is a surgical procedure mostly used for older patients suffering from severe osteoarthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Numerous studies have referred to transfer metatarsalgia of the 2nd to 5th metatarsal head, weakness in plantar flexion, and shortening and elevation of the big toe [3, 6, 12, 20]. Several risk factors and causes for osteonecrosis (ON; also known as avascular necrosis) of the 1st metatarsal head are known, such as overloading of the 1st metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint [21, 25]. ON of the 1st metatarsal head has also been seen after distal osteotomies of the 1st metatarsal (in combination or without lateral soft tissue release) performed to correct hallux valgus [7, 8].

To avoid those side effects, modifications of the Keller procedure were described. Hamilton and colleagues reported promising results with a modification of resection arthroplasty called ‘capsular interposition arthroplasty’ (IA) [9, 10].

The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical and radiological outcomes of both procedures.

Materials and method

Indication for operative treatment with IA or resection arthroplasty was severe osteoarthritis of the 1st MTP joint, known as hallux rigidus. On preoperative radiographs, the extent of hallux rigidus was assessed, using Hattrup and Johnson’s classification: grade I, osteophyte formation mild to moderate, good preservation of joint space; grade II, moderate formation of osteophytes, joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis; grade III, marked osteophyte formation, loss of the visible joint space.

All patients included in this study suffered from disabling pain and limited range of motion and did not respond to non-surgical treatment. IA was carried out if patients’ radiographs showed moderate-to-severe degenerative changes in the 1st MTP joint (Hattrup and Johnson’s classification grades II or III). In our department, milder forms of hallux rigidus (grade I) were treated conservatively or by cheilectomy. IA was also not carried out in cases of rheumatoid arthritis or other systemic inflammatory diseases. In 1999, capsular interposition arthroplasty was performed on 40 feet of 27 consecutive patients suffering from osteoarthritis of the 1st MTP joint. Of 14 patients (six male, eight female), 22 feet were included in this study (group 1); the other patients were lost to follow-up (they could not be reached or they did not show up for the follow-up examination). Mean range of motion in these patients was, on average, 47.0° [standard deviation (SD) 24.9°]. On preoperative radiographs, 3/22 feet were staged as grade III, 19/22 as grade II.

These results were compared with the outcome of 30 feet of 22 patients (12 male, ten female) treated with resection arthroplasty (group 2). These patients were all surgically treated by the senior author between 1999 and 2001. A further 23 feet of 15 patients treated with resection arthroplasty by the senior author were lost to follow-up. The indication for resection arthroplasty was the same as for IA.

The mean age was 55.3 years (37.6 to 71.2 years) in group 1 and 57.8 years (43.5 to 75.6 years) in group 2. The age distribution of our patients at surgery did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.633).

The mean follow-up period was 15.1 months, range 6 to 27 months, and did not differ between groups (group 1, 16.5 months, group 2, 14.1 months; P = 0.143).

Both surgical procedures were performed under ankle block anaesthesia.

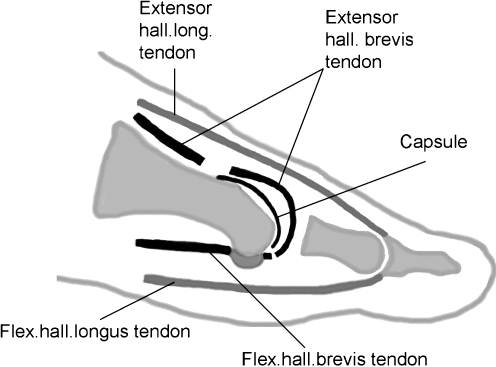

Capsular interposition arthroplasty was performed through a medial skin incision over the 1st MTP joint. The joint capsule was exposed, incised medially and mobilised. Then, cheilectomy was performed; osteophytes on the medial side of the 1st metatarsal head were removed if necessary. The base of the proximal phalanx was cleared of the joint capsule, the short flexors and extensors. Approximately one-third of the proximal phalanx was resected with an oscillating saw. The extensor digitorum brevis tendon was then identified and cut 30 mm to 40 mm proximal to the joint line. Capsular interposition was performed by further mobilisation of the dorsal joint capsule and suture fixation to the proximal stumps of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon on the plantar aspect of the joint with a non-resorbable suture material. Closure of the joint capsule was carried out without any tensioning (Fig. 1). To allow early passive mobilisation of the 1st MTP joint no K-wire fixation was performed, in contrast to the description by Hamilton and co-workers [10].

Fig. 1.

Surgical procedure of interposition arthroplasty

For resection arthroplasty, medial skin and capsular incisions were performed. After cheilectomy and removal of medial osteophytes of the 1st metatarsal head, the base of the proximal phalanx was cleared of soft tissues as described above. Approximately one-third of the proximal phalanx was resected, then the joint capsule was closed without tensioning.

Postoperative treatment was alike for both operating techniques: patients were allowed full weight-bearing from the first postoperative day using a stiff-soled shoe for 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the surgeon’s assessment of local swelling and pain 4 weeks postoperatively.

At follow-up, the patients’ satisfaction and clinical outcomes were assessed. Patients were asked to grade their satisfaction with the outcome of the surgical procedure as excellent/good/fair/poor. The range of motion of the 1st MTP joint was examined and compared with preoperative values. Pre- and postoperatively, the hallux metatarsophalangeal–interphalangeal scale, according to the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS), was used for clinical evaluation. Pain, limitation in activity, footwear requirements, MTP and interphalangeal (IP) joint motion, MTP–IP stability, tender callus and alignment contribute to this score (maximum = 100 points). For radiological evaluation, dorsal–plantar radiographs of the weight-bearing joint and radiographs of the unloaded joint in 45° pronation were assessed. Preoperatively and at follow-up the width of the joint space of the 1st MTP joint, the metatarsophalangeal angle, and the length of the proximal phalanx were evaluated. On preoperative radiographs, radiological signs of osteoarthritis were found in all patients; the average width of the joint space was 1 mm for both groups. At follow-up, radiographs were also reviewed for signs of ON of the 1st metatarsal head and they were categorised according to the classification by Meier and Kenzora [17] [mottling’ (pre-collapse phase/stage 1), and partial or total ON (collapse phase/stage 2)], depending on the size of the osteonecrotic area and the location on the 1st metatarsal head. The term ‘partial’ was used when less than 50% of the articulating surface was destroyed due to ON).

Group differences were assessed by independent sample t-tests, for quantitative data, or with cross-tables corrected for small samples (Gart’s I-test), for categorical data. The change in clinical outcome was evaluated by one-factorial analyses of variance for repeated measures. Generally, a significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Results

The result of the surgical procedure was graded as excellent or good by 77% of patients treated with IA and by 73% of patients who underwent resection arthroplasty (Keller) and did not differ significantly between either technique (P = 0.932; Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ satisfaction after interposition arthroplasty (group 1) and resection arthroplasty (group 2)

| Patients’ satisfaction | Group 1 | Group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Interposition arthroplasty n1 = 22 feet | Resection arthroplasty n2 = 30 feet | |

| Excellent | 14 feet (63%) | 19 feet (63%) |

| Good | 3 feet (14%) | 3 feet (10%) |

| Fair | 4 feet (18%) | 5 feet (17%) |

| Poor | 1 foot (5%) | 3 feet (10%) |

The metatarsal index was evaluated for all patients and, again, did not differ between groups (P = 0.890). A plus index (the 1st metatarsal was found to be longer than the 2nd on dorsoplantar radiographs of the weight-bearing joint) was found for five feet in group 1 and for eight feet in group 2, a ± index (i.e. equal lengths of the 1st and 2nd metatarsals) was seen for 11 feet for group 1 and 13 feet for group 2. A minus index was found for six feet in group 1 and for nine feet in group 2.

The range of motion (ROM) of the 1st MTP joint was examined and compared with the preoperative values. The average preoperative ROM was 47.2° (SD 25.4°) for group 1 and 28.2° (SD 15.2°) for group 2. The average increase in ROM was 19.3° (range −20° to +40°; SD 14.6°) and 24.0° for group 2 (range 0° to 60°; SD 15.7°) .The average increase did not differ significantly between either technique (P = 0.278). At follow-up, the width of the joint space was 2.4 mm for group 1 (range 1 to 6 mm; SD = 1.2) and also 2.4 mm for group 2 (range 0.5 to 4 mm; SD = 1.1); (P = 0.966).

The AOFAS hallux metatarsophalangeal–interphalangeal scale preoperatively and at follow-up did not show a significant pre- and postoperative group difference (P = 0.077). For group 1 (IA) the average preoperative score was 57 points and the average increase was 32 points (range −28 to +60 points; SD = 25.7). The preoperative score for group 2 (resection arthroplasty) was 50 points; the average increase was 38 points (range −32 to +65 points; SD = 21.6).

As the hallux metatarsophalangeal–interphalangeal scale (100 points) is composed of the categories ‘pain’ (40 points), ‘function’ (40 points) and ‘alignment’ (20 points), these three domains were analysed in detail for both groups. Although alignment is generally not considered an important factor in hallux rigidus, this part of the score was also analysed for the sake of completeness. Concerning pain, the score improved, on average, from 15 points preoperatively to 36 points at follow-up for group 1 and from 10 points to 36 points for group 2. The average increase in the category ‘function’ was from 30 to 39 points for group 1 and from 28 to 37 points for group 2. In the category ‘alignment’ the average preoperative value was 12 points in both groups, and it had changed to 15 points in group 1 and 14 points in group 2 at follow-up. All three domains did not show significant group differences (pain P = 0.256; function P = 0.067; alignment P = 0.612).

At follow-up, signs of ON of the 1st metatarsal head could be seen on radiographs. The radiographic changes according to Meier and Kenzora [20] are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Radiological changes of the 1st metatarsal head at follow-up pre-collapse-phase/stage 1 of osteonecrosis according to the Meier and Kenzora classification: mottling, collapse phase/stage 2 partial necrosis (osteonecrotic area less than 50% of the articulating surface) and total necrosis of the 1st metatarsal head

| Change | Group 1 | Group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Interposition arthroplasty n1 = 22 feet | Resection arthroplasty n2 = 30 feet | |

| Normal X-ray findings | 13 | 21 |

| Mottling | 0 | 2 |

| Partial necrosis | 6 | 5 |

| Total necrosis | 3 | 2 |

In total, radiographic sign of ON of the 1st metatarsal head were found in nine of 22 feet in group 1 and in nine of 30 feet in group 2.

Partial necrosis was found in different locations on the 1st metatarsal head. Depending on which part of the 1st metatarsal head and the articulating surface was affected, partial ON was classified as medial, lateral or central. The location of these changes did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.563).

These radiological findings were also set in relation to the AOFAS score. The outcome of patients showing radiological signs of ON of the 1st metatarsal head in both groups was compared with that of patients with normal radiograph findings. Patients with normal X-ray findings differed from patients with mottling or partial or total necroses only in that they were significantly older (P = 0.013; normal X-ray findings, mean = 58.9, SD = 8.1, minimum = 44.8, maximum = 75.6; mottling, or partial or total necrosis, mean = 51.4, SD = 8.5, minimum = 37.6, maximum = 67.0). However, the clinical outcome did not differ significantly between patients with normal X-ray results and patients with mottling, or partial or total necrosis, according to patients’ satisfaction (P = 0.495), AOFAS score (P = 0.330) and increase in the AOFAS score (P = 0.607), as summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical outcome compared with radiological findings of patients treated with either IA or resection arthroplasty

| Parameter | Radiological findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal X-ray results, n1 = 34 feet | Mottling, partial or total necrosis, n2 = 18 feet | |

| Patients’ satisfaction | ||

| Excellent | 19 (56%) | 14 (77%) |

| Good | 4 (12%) | 2 (11%) |

| Fair | 8 (23%) | 1 (6%) |

| Poor | 3 (9%) | 1 (6%) |

| AOFAS score preoperatively | 52.6 ± 13.2 points | 53.3 ± 18.8 points |

| AOFAS score postoperatively | 86.5 ± 16.4 points | 90.8 ± 7.8points |

| Increase in AOFAS score | 33.9 ± 25.3 points | 37.5 ± 19.8 points |

Complications

At follow-up, metatarsalgia of the 2nd ray was reported by three patients in group 1; one of these patients had been treated subsequently with a shortening osteotomy. Metatarsalgia was found in four patients in group 2. The development of metatarsalgia was not correlated with the metatarsal index. In these seven cases of metatarsalgia, a metatarsal +index was seen in four feet, a −index in one foot and a ±index in two feet. Morton’s metatarsalgia was found in one patient in group 2, and hypoaesthesia in the big toe was found in two patients in each group. A floating hallux was seen in one foot in group 1 and in three feet in group 2. In group 2 three patients described persisting pain in the 1st MTP joint; one patient reported mild instability in the MTP joint and had developed a mild hallux varus of 5°. Algodystrophy occurred in one patient in group 1. One patient in group 2, who had undergone operations on both feet, reported protracted night pain in both feet for approximately 2 months postoperatively. Ossification of the interposed capsule was seen in one patient in group 1, although this patient showed a good clinical result (AOFAS score 90 points).

Discussion

A variety of different surgical procedures is described for the treatment of hallux rigidus. Patients who suffer only from mild osteoarthritis of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint may benefit from cheilectomy [11, 14, 16]. In severe cases of hallux rigidus arthrodesis may relieve pain but leads to limitation of activity and footwear [2]. Implant arthroplasty preserves motion, but high rates of implant loosening and bone resorption have been reported [5].

Resection arthroplasty is a common procedure for treatment of hallux rigidus [3, 20]. Promising results with tendon interposition in the 1st MTP joint were reported by Barca [1] and Coughlin and Shurnas [4]. Hamilton and colleagues presented the ‘capsular interposition arthroplasty’ procedure [9, 10] and reported good clinical and radiological results. Transfer metatarsalgia and weakness in push-off or plantarflexion were not seen. This procedure has been recommended for younger and more active patients.

However, Lau and Daniels [14] found a poor outcome in patients treated by IA compared with those who underwent cheilectomy. Reviewing the literature, we could not find any publications comparing IA directly with resection arthroplasty.

Osteonecrosis, also known as avascular necrosis, of the 1st metatarsal head has been reported to occur under certain circumstances, such as excessive load bearing and overuse of the 1st MTP joint in dancers [21, 25]. Several authors have seen cases of ON after hallux valgus surgery, mostly distal metatarsal osteotomies (often combined with lateral soft tissue releases) or silastic spacer implantation [17, 18, 22–24].

It has been speculated that blood supply to the 1st metatarsal head is diminished in cases of severe osteoarthritis of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint [25]. At surgery, blood vessels in the periosteum or the joint capsule may be further damaged or disrupted because of excessive dissection or too much tensioning of the tendon stumps and the capsular tissue, leading to insufficient blood supply to the 1st metatarsal head and then to ON. Mobilisation of the dorsal capsule and soft tissue has to be performed to a far greater extent in IA than in resection arthroplasty. This may worsen blood supply to the 1st metatarsal head and favour ON.

In this study a short-term follow-up period of 14 to 15 months was chosen to find radiological signs of stage 1 and stage 2 of ON at their full extent before secondary changes took place (such as remodelling of the bone or progression to stage 3—persistent collapse of the 1st metatarsal head and osteoarthritis of the MTP joint) [17]. Radiographic signs of ON of the 1st metatarsal head were found after IA and after resection arthroplasty, with a slightly (but not statistically significant) higher frequency in IA. However, these radiological changes associated with ON did not correlate with the clinical outcome of patients. Only a few patients have reported clinical signs typical of ON, such as protracted night pain for some weeks or months after surgery. Both the patients’ assessments of the surgical procedure and the AOFAS scores were similar in patients with ON and in patients showing normal radiograph findings at follow-up. Our data suggests that ON of the 1st metatarsal head may take place without any major clinical symptoms in many patients and does not necessarily affect the long-term result of IA or resection arthroplasty.

Comparing IA with the well-established method of resection arthroplasty, we found no statistically significant difference in the clinical outcome for either group. The postulated clinical benefits of IA [10] were not confirmed by our findings. This could be due to necrosis or resorption of the interposed capsule and tendon tissue because of insufficient blood supply to these structures. The interposed tissues may also be mechanically unsuitable as a spacer in this joint.

On the other hand, possible disadvantages of IA are the prolonged time needed for surgery, the need for additional dissection of the extensor hallucis brevis tendon, and a possibly slightly higher rate of ON of the 1st metatarsal head.

Conclusion

We concluded that IA did not show better clinical or radiological outcomes than did the Keller procedure.

References

- 1.Barca F. Tendon arthroplasty of the first metatarsophalangeal joint in hallux rigidus: preliminary communication. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;8:222–228. doi: 10.1177/107110079701800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beauchamp CG, Kirby T, Rudge SR, Worthington BS, Nelson J. Fusion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint in forefoot arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;190:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleveland M, Winant EM. An end-result study of the Keller operation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PJ. Soft-tissue arthroplasty for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:661–672. doi: 10.1177/107110070302400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cracchiolo A, Swanson A, Swanson GD. The arthritic great toe metatarsophalangeal joint: a review of flexible silicone implant arthroplasty from two medical centers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;157:64–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhanendran M, Pollard JP, Hutton WC. Mechanics of the hallux valgus foot and the effect of Keller’s operation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:1007–1012. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Easley ME, Kelly IP. Avascular necrosis of the hallux metatarsal head. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5:591–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green MA, Dorris MF, Baessler TP, Mandel LM, Nachlas MJ. Avascular necrosis following distal Chevron osteotomy of the first metatarsal. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1993;32:617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton WG, O’Malley MJ, Thompson FM, Kovatis PE. Roger Mann Award 1995. Capsular interposition arthroplasty for severe hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:68–70. doi: 10.1177/107110079701800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton WG, Hubbard CE. Hallux rigidus. Excisional arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5:663–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattrup SJ, Johnson KA. Subjective results of hallux rigidus following treatment with cheilectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:182–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry AJ, Waugh W, Wood H. The use of footprints in assessing the results of operations for hallux valgus. A comparison of Keller’s operation and arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:478–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller WL. The surgical treatment of bunions and hallux valgus. NY Med J. 1904;80:741–742. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau JT, Daniels TR. Outcomes following cheilectomy and interpositional arthroplasty in hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:462–470. doi: 10.1177/107110070102200602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann RA, Oates JC. Arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Foot Ankle. 1980;1:159–166. doi: 10.1177/107110078000100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann RA, Clanton TO. Hallux rigidus: treatment by cheilectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier PJ, Kenzora JE. The risks and benefits of distal first metatarsal osteotomies. Foot Ankle. 1985;6:7–17. doi: 10.1177/107110078500600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meisenhelder DA, Harkless LB, Patterson JW. Avascular necrosis after first metatarsal head osteotomies. J Foot Surg. 1984;23:429–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moberg E. A simple operation for hallux rigidus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;142:55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson EG. Keller resection arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1990;13:1049–1053. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19900901-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sammarco GJ, Miller EH. Forefoot conditions in dancers: part I. Foot Ankle. 1982;3:85–92. doi: 10.1177/107110078200300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas RL, Espinosa FJ, Richardson EG. Radiographic changes in the first metatarsal head after distal chevron osteotomy combined with lateral release through a plantar approach. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:285–292. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson SV, Jones RO, Sisk LE, Sunshein KF, Manen JW. Austin bunionectomy: postoperative MRI evaluation for avascular necrosis. J Foot Surg. 1992;31:469–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams WW, Barrett DS, Copeland SA. Avascular necrosis following chevron distal metatarsal osteotomy: a significant risk? J Foot Surg. 1989;28:414–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zollinger H (1988) Osteonekrosen der Metatarsaleköpfchen. Bd 53. Enke, Stuttgart