Abstract

The objective of this meta-analysis was to compare the fixation outcome of the Gamma nail and dynamic hip screw (DHS) in treating peritrochanteric fractures. Relevant randomised controlled studies were included, and the search strategy followed the requirements of the Cochrane Library Handbook. Methodological quality was assessed and data were extracted independently. Seven studies involving 1,257 fractures were included which compared the effect of the Gamma nail and DHS. The results showed a higher rate of postoperative femoral shaft fracture with the Gamma nail compared to the DHS [relative risk (RR): 7.27, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.83–18.70, P < 0.0001] but no statistical differences in wound infection (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.56–1.86), mortality (RR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.81–1.24), re-operation (RR: 1.64, 95% CI: 0.91–2.95) and walking independently after rehabilitation (RR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.60–1.33). It seemed that there were no obvious advantages of the Gamma nail over the DHS in treating peritrochanteric fractures.

Introduction

An increase in the elderly population has resulted in a higher incidence of peritrochanteric fractures of the femur. To prevent the complications of prolonged immobilisation, timely management with appropriate methods providing sound stabilisation of the fracture and early mobilisation of the patients becomes increasingly important for these fractures.

Generally, Gamma nail and dynamic hip screw (DHS) internal fixation are the two primary options. For stable and minimally displaced peritrochanteric fractures, the DHS fixation produces reproducibly reliable results [1, 2]. However, in unstable fractures, the device performs less well with a relatively higher incidence of internal fixation failure [3–5]. The intramedullary nail such as a Gamma nail appears to have theoretical advantages over the DHS in the management of peritrochanteric fractures: lesser surgical trauma biologically and greater strength biomechanically [6–8].

Recently, a number of randomised trials were performed to compare the management of peritrochanteric fractures using the DHS to that using the Gamma nail [9–11]. These trials have overcome the limitations of observational studies by decreasing bias through randomisation. However, the optimal management of peritrochanteric fractures remains controversial. On the basis of other studies [12–14], modifications to the design of the Gamma nail were performed which made the insertion of the nail more and more minimally invasive and convenient. Moreover, a number of further randomised trials have since been undertaken. This has enabled a more extensive meta-analysis of prospective randomised controlled trials of the Gamma nail versus DHS devices for the fixation of peritrochanteric fractures.

Methods

We searched for relevant studies according to the search strategy of the Cochrane Collaboration. It included searching the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group Trials Register, computer searching of MEDLINE, EMBASE and Current Contents, and hand searching of orthopaedic journals. All databases were searched from the earliest records to August 2008. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used in selecting the procedure were: (1) target population: individuals with peritrochanteric fractures classified as peritrochanteric or intertrochanteric with or without subtrochanteric extension, excluding the pathological fractures; (2) intervention: DHS fixation compared with Gamma nail fixation; (3) methodological criteria: prospective, randomised or pseudo-randomised controlled trials. Duplicate or multiple publications of the same study were not included. In order to meet the constraints for the reference section of this article, studies that have not been published as complete, peer-reviewed journal articles have been referenced to the Cochrane review [15].

Data were collected by two independent researchers who screened titles, abstracts and keywords both electronically and by hand; differences were resolved by discussion. Full texts of citations that could possibly be included in the study were retrieved for further analysis. The assessment method from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was used to evaluate the studies in terms of blinding, allocation concealment, follow-up coverage and quality level [according to whether allocation concealment was adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C) or that allocation concealment was not used (D) as a criterion to assess the study quality]. The principle outcomes for the purpose of this meta-analysis were those related to fracture fixation complications during the follow-up period of each study. Wound infection rate, mortality, postoperative femoral shaft fracture, re-operation rate for fracture fixation failure and percentage of walking independently after rehabilitation were the main criteria which the meta-analysis evaluated to compare the included studies. We did not undertake a subgroup analysis for different fracture types because not all of the included studies described the fracture types.

In each study the relative risk (RR) was calculated for dichotomous outcomes, and weighted mean difference was calculated for continuous outcomes using the software Review Manager 5.0, both adopted a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity was tested for by using both the chi-square test and I-square test. A significance level of less than 0.10 for the chi-square test was interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity. I-square was used to estimate total variation across studies. When there was no statistical evidence of heterogeneity, a fixed effect model was adopted; otherwise, a random effect model was chosen. We did not include the possibility of publishing bias due to the small number of studies included.

Results

A total of 256 articles published from 1969 to August 2008 comparing the Gamma nail and DHS were retrieved: 198 were from MEDLINE, 47 from the Cochrane Library and 11 from the EMBASE Library. Among them, 20 trials met the inclusion criteria. After excluding non-randomised control trials and retrospective articles, seven randomised controlled trials were included. The number of fractures in the single study included ranged from 95 to 400. There were a total of 1,257 fractures. One research paper targeted Asian patients, and the other six targeted Caucasians. The average age was 77.9–83 and all studies but one had more female than male patients; 614 fractures were managed with Gamma nails and 643 managed with DHS. Most research evaluated mortality rate, wound infection rate, postoperative femoral shaft fracture and re-operation rate; two evaluated the percentage of walking independently after rehabilitation. The quality of the seven studies included was level B because the allocation concealment was unclear according to the evaluation criteria mentioned above (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Description of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Studies | Age (years): Gamma nail/DHS | Men (%) | Target population | Length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leung et al. [11] | 80.9 ± 8.4/78.3 ± 9.5 | 29.6 | Hong Kong | 6 months |

| Madsen et al. [16] | 78.1 ± 10.3/77.9 ± 11.0 | 16.3 | Norway | 6 months |

| O’Brien et al. [9] | 83 (57–95)/77 (39–94) | 25.7 | Canada | 2 months |

| Adams et al. [10] | 81.2 (48–99)/80.7 (32–102) | 22.0 | UK | 12 months |

| Radford et al. [13] | 83 (60–90)/78 (60–90) | 77.5 | UK | 12 months |

| Butt et al. [17] | 79 (55–92)/78 (47–101) | 30.5 | UK | NA |

| Bridle et al. [12] | 81/82.7 | 16.0 | UK | 6 months |

Table 2.

Description of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Studies | No. of fractures in each group | Outcomesa | Publication year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma nail | DHS | |||

| Leung et al. [11] | 113 | 113 | 1, 2, 3, 5 | 1992 |

| Madsen et al. [16] | 50 | 85 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | 1998 |

| O’Brien et al. [9] | 53 | 49 | 1, 3, 4 | 1995 |

| Adams et al. [10] | 203 | 197 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 2001 |

| Radford et al. [13] | 100 | 100 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1993 |

| Butt et al. [17] | 47 | 48 | 1, 2, 3 | 1995 |

| Bridle et al. [12] | 49 | 51 | 1, 2, 3 | 1991 |

a1 wound infection, 2 mortality, 3 postoperative femoral shaft fracture rate, 4 re-operation rate for fracture fixation failure, 5 percentage of walking independently after rehabilitation

Table 3.

Methodological quality of included studies

| Studies | Baseline | Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Loss to follow-up | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Fracture type | ||||||

| Leung et al. [11] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| Madsen et al. [16] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| O’Brien et al. [9] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| Adams et al. [10] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | B |

| Radford et al. [13] | Comparable | Comparable | Incomparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | B |

| Butt et al. [17] | Comparable | Comparable | Comparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | B |

| Bridle et al. [12] | Comparable | Comparable | Incomparable | Inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | B |

Wound infection

In the seven studies providing postoperative wound infection data, there were 1,213 fractures included. There were 19 cases of wound infection among the 594 fractures managed with Gamma nails, and 20 cases were observed among the 619 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity (χ2 = 6.86, P = 0.33, I2 = 13%). Data pooled by a fixed effects model indicated that there was no statistical difference in wound infection rate between the Gamma nail and DHS (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.56-1.86, P = 0.94) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of wound infection rate between the Gamma nail and DHS

Mortality

Six articles including 1,156 patients were included, providing mortality data within 12 months or less of the initial operation. One-hundred and twenty-six Among the 562 patients managed using Gamma nails 126 deaths occurred, and among the 594 patients managed using DHS 129 deaths were observed. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity. Data pooled using a fixed effects model indicated that there was no difference in mortality rate between the Gamma nail and DHS (RR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.81–1.24, P = 0.98) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mortality between the Gamma nail and DHS

Postoperative femoral shaft fracture

Seven studies provided data concerning postoperative femoral shaft fracture. Among the 594 fractures managed with Gamma nails 32 cases of postoperative femoral shaft fracture were observed, and three cases were observed among the 623 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity. Data pooled using a fixed effects model indicated a lower femoral shaft fracture rate of DHS compared to Gamma nail (RR: 7.27, 95% CI: 2.83–18.70, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of postoperative femoral shaft fracture rate between the Gamma nail and DHS

Re-operation for fracture fixation failure

Four studies provided data on re-operation rate for fracture fixation failure. Among the 405 fractures managed with Gamma nails 27 cases of subsequent operation were observed; 18 cases were observed among the 431 fractures managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated no statistical evidence of heterogeneity. Data pooled by a fixed effects model and the meta-analysis indicated a higher rate of re-operation in the Gamma nail group, but the number does not reach statistical significance (RR: 1.64, 95% CI: 0.91–2.95, P = 0.10) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of re-operation rate between the Gamma nail and DHS

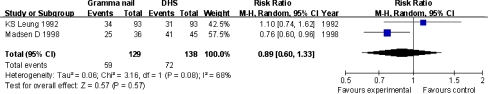

Walking independently after rehabilitation

Two studies that included 267 patients provided data on the rate of walking independently six months after the operation. Among the 129 patients managed with Gamma nails 59 cases of independent walking were observed, and 72 cases were observed among the 138 patients managed with DHS. Heterogeneity tests indicated statistical evidence of heterogeneity (χ2 = 3.16, P = 0.08, I2 = 68%). Data pooled using a random effects model indicated no statistical difference between the Gamma nail group and DHS group (RR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.60–1.33, P = 0.57) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of walking independently between the Gamma nail and DHS

Discussion

The present operative management of most of the peritrochanteric fractures is internal fixation with intramedullary implants such as the Gamma nail or extramedullary implants such as the DHS. The common merits of both devices are non-exposure of fracture ends and limited effect on blood supply to the fractures. They both keep to the dynamic compressive principle of the lag screw, firmly fixing the femoral head with the femoral shaft and thus stabilising implantation in the fracture part. Fixation is realised by applying biotype compression to enable the patients to conduct functional exercises and to recover all or part of the limb function. However, there are still disagreements over the best internal fixation in the management of peritrochanteric fractures, especially unstable types such as reverse intertrochanteric fractures [18–20].

It was previously held that the Gamma nail in the management of peritrochanteric fractures theoretically lifted the weight off the inner cortex of the femoral neck more than the outer cortex. Compared to the DHS with plates, intramedullary nails, being more recently developed, were mechanically advantageous because they were internal. The bending moment in the joint on the intramedullary nail and the screw was less than in that of the plate and the screw.

Our research method is commonly used and is designed to allow for [10] reproducible research selection and evaluation criteria, and to explore the possible reasons for the differences in research. Articles in English journals are chosen based on the theory that although meta-analysis confined to language does not cause bias [21], the possibility of bias is not excluded.

Although the search strategy is broad and extensive, not all related randomised trials are included mainly because of: publication bias, which may exclude obvious outcome differences of the two treatment methods [22], or selection bias, which may exclude selective studies that had preference for some kind of treatment [23]. Strict searches in the library and included bibliographies are conducted to reduce bias.

This meta-analysis indicates that the Gamma nail and DHS share no obvious statistical difference in the aspects of mortality rate, wound infection rate, re-operation rate for fracture fixation failure and percentage of walking independently after rehabilitation. The duration of operation with the Gamma nail is shorter, but the risk of postoperative femoral shaft fracture is greater for the Gamma nail. Our meta-analysis showed conclusively that the risk of postoperative femoral shaft fracture is greater in the Gamma nail group than DHS group. This leads us to recommend that DHS fixation is a safer and more dependable procedure than Gamma nail fixation vis-a-vis the complications after operation and that it may be the first option for the treatment of peritrochanteric fractures.

Clearly, there are serious limits to the power of our study. The quality of the trials was generally low, and the number of trials included was low. In addition to having methodological issues, the included trials had a relatively low number of patients.

In summary, although our data showed that there was a higher, statistically significant rate of postoperative femoral shaft fracture in the Gamma nail group, the overall quality of the studies and the breadth of the studies clearly indicate the need for further research. With future modifications to the design of these two kinds of devices, more high quality randomised control trials and further studies need to be run to observe whether these changes lead to outcomes for Gamma nails becoming equivalent or even superior to DHS.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by National Basic Research Program of China (Contract Grant No. G2005cb623901) and by National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (30271317).

References

- 1.Clawson DK. Trochanteric fractures treated by the sliding screw plate fixation method. J Trauma. 1964;4:737–752. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RF, Gustilo RB, Premer RF. Analysis of six hundred and twenty-two intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:216–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schipper IB, Marti RK, Werken C. Unstable trochanteric femoral fractures: extramedullary or intramedullary fixation. Review of literature. Injury. 2004;35:142–151. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis TR, Sher JL, Horsman A, et al. Intertrochanteric femoral fractures. Mechanical failure after internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:26–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B1.2298790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker MJ. Cutting-out of the dynamic hip screw related to its position. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:625. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B4.1624529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadowski C, Lübbeke A, Saudan M, Riand N, Stern R, Hoffmeyer P. Treatment of reverse oblique and transverse intertrochanteric fractures with use of an intramedullary nail or a 95 degrees screw-plate: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:372–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlowodzki M, Bhandari M, Brown GA. Misconceptions about the mechanical advantages of intramedullary devices for treatment of proximal femur fractures. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:169–170. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SR, Kang JS, Kim HS, Lee WH, Kim YH. Treatment of intertrochanteric fracture with the Gamma AP locking nail or by a compression hip screw—a randomised prospective trial. Int Orthop. 1998;22:157–160. doi: 10.1007/s002640050231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien PJ, Meek RN, Blachut PA, Broekhuyse HM, Sabharwal S. Fixation of intertrochanteric hip fractures: gamma nail versus dynamic hip screw. A randomized, prospective study. Can J Surg. 1995;38:516–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams CI, Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Prospective randomized controlled trial of an intramedullary nail versus dynamic screw and plate for intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:394–400. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung KS, So WS, Shen WY, Hui PW. Gamma nails and dynamic hip screws for peritrochanteric fractures. A randomised prospective study in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:345–351. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B3.1587874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridle SH, Patel AD, Bircher M, Calvert PT. Fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. A randomised prospective comparison of the gamma nail and the dynamic hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:330–334. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radford PJ, Needoff M, Webb JK. A prospective randomised comparison of the dynamic hip screw and the gamma locking nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(5):789–793. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aune AK, Ekeland A, Odegaard B, Grøgaard B, Alho A. Gamma nail vs compression screw for trochanteric femoral fractures. 15 reoperations in a prospective, randomized study of 378 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:127–130. doi: 10.3109/17453679408995418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker MJ, Handoll HHG (2004) Gamma and other cephalocondylic intramedullary nails versus extramedullary implants for extracapsular hip fractures (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester

- 16.Madsen JE, Naess L, Aune AK, Alho A, Ekeland A, Strømsøe K. Dynamic hip screw with trochanteric stabilizing plate in the treatment of unstable proximal femoral fractures: a comparative study with the Gamma nail and compression hip screw. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(1):241–248. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butt MS, Krikler SJ, Nafie S, Ali MS. Comparison of dynamic hip screw and gamma nail: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Injury. 1995;26(2):615–618. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00126-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ecker ML, Joyce JJ, 3rd, Kohl EJ. The treatment of trochanteric hip fractures using a compressing screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen JS, Sonne-Holm S, Tøndevold E. Unstable trochanteric fractures. A comparative analysis of four methods of internal fixation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51(6):949–962. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones HW, Johnston P, Parker M. Are short femoral nails superior to the sliding hip screw? A meta-analysis of 24 studies involving 3,279 fractures. Int Orthop. 2006;30:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Pham B, Klassen TP, Schulz KF, Berlin JA, Jadad AR, Liberati A. What contributions do languages other than English make on the results of meta-analyses? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(3):964–972. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO. Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on Meta-Analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):167–171. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00172-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailar JC., 3rd The promise and problems of meta-analysis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(8):559–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]