Abstract

Since its inauguration by Gerber in 1988, the latissimus dorsi transfer has become an established surgical option for non-reconstructable, massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. We describe 26 consecutive patients, all of whom underwent a latissimus dorsi transfer using a modified single incision mini-invasive Herzberg transfer. The primary focus of this paper was to compare the applied clinical results of this new technique with the published results of the Gerber technique. Following transfer of the latissimus dorsi to restore external rotation, 26 patients were evaluated. The mean age was 60 ± 18 years. The patients were examined after surgery at an average of 24 months (range: 12–41). The unweighted Constant score rose from 20 (range: 13–34) to 56 (range: 63–81). The acromiohumeral distance remained statistically unchanged from an initial value of 4.7 mm (1–9 mm) to a postoperative value of 4.8 (2–11 mm). In the Hamada classification the level of rotator cuff defect arthropathy increased from 1.7 (1–3) to 1.8 (1–3). On the basis of its low morbidity rate, the latissimus dorsi transfer in Herzberg’s modified technique is a sensible alternative to the technique initially described by Gerber, especially when the initial situation exhibits pre-existing weakness of the deltoid muscle.

Introduction

The indication for a latissimus dorsi transfer is found in active patients exhibiting combined defects of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons with consequent uncompensated external rotation and abduction weaknesses and desiring functional restoration. Gerber initially demonstrated the technique of the latissimus dorsi transfer in 1988 [1]. This technique currently enjoys quite a good standing and acceptance on the basis of the data and material available, the number of patients as well as the appearance in follow-up examinations [2, 3].

The aims of this technique are to cover the cranial defect, re-establish a wide range of mobility in external rotation and abduction and develop an active depressor effect. The latissimus dorsi muscle is mobilised through a dorsal incision and then reinserted at the greater tuberosity through a transacromial access.

This technique showed better clinical results in young, well motivated patients desiring a high functional restitution and an intact subscapularis tendon [3].

Alternatively to the latissimus dorsi transfer, the Celli technique can be implemented for the same indication and using the same access, the primary difference being the mobilisation and reattachment of the teres major muscle [4]. However, the teres major has a smaller pivoting radius and has a less reliable reattachment on account of its very short and weak tendon insertion. Augereau and Apoil inaugurated in 1988 the deltoid muscle flap in the treatment of massive rotator cuff tears [5], whereas other techniques like patch graft [6] have not achieved wide acceptance.

For older patients not needing such a high level of functional restitution but exhibiting a strong external rotation lag sign as well as a pathological hornblower’s sign, a further alternative is available: the modified L’Episcopo procedure. This technique involves the simultaneous transfer of both the latissimus and the teres major and aims to restore the balance between internal and external rotation while neglecting the cranial closure of the rotator cuff [7].

While originally used to treat plexus lesions occurring during birth [8], this procedure was modified within the framework of major rotator cuff tear operations. This is an especially attractive option when the acromiohumeral gap measures less than 5 mm since this lack of space makes the reinsertion at the greater tuberosity difficult and a mechanical subacromial conflict can result.

The basic principle of the L’Episcopo operation is transfer of the communal insertion tendon from the medial side of the proximal humerus to a lateral site near the surgical neck. This transforms these muscles from internal to external rotators.

Herzberg’s examinations [9] led to a further therapeutic alternative. He describes muscle excursions of the shoulder in an anatomical examination. In 2001 he also discovered superior rotation and movement resulting from the reinsertion of the latissimus dorsi at the site of the infraspinatus insertion zone [10]. Since the insertion site of the infraspinatus can easily be accessed following the muscle detachment, this transfer can be completed by means of only one incision. Preliminary results of clinical trials of the “single-incision technique” have just recently been published [11]. One study showed that the Constant score increased with a mean follow-up time of 32 months from 46.5 to 74.6 points [11]. Contraindications to all of the procedures listed above are simultaneous irreparable subscapularis tears as well as deltoid palsy and advanced osteoarthritis in elderly patients. In these cases a technique combining an inverse prosthesis and a latissimus dorsi transfer is effective in restoring active elevation and external rotation, as described in recent publications [12, 13].

Since one can largely expand without mobilisation of the latissimus dorsi, a minimally invasive alternative was developed which involves making a 6- to 8-cm incision without damaging neurovascular structures or the deltoid, thereby potentially reducing co-morbidities. In a prospective, preliminary step, the results and complications of this new technique were to be examined, prior to a randomised trial comparing this technique and the Gerber transfer.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 26 patients with irreparable, massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears were recruited from 2004 to 2007 in a prospective consecutive study and underwent transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendons according to the Herzberg technique. The average age of the patients at surgery was 64 years, ranging from 41 to 78. They exhibited the classic symptoms for an average of 30.6 months (6–120 months) and included a total of eight previous operations: two cases of arthroscopic subacromial decompression, two cases of tuberculoplasty with tenotomy of the long head of the biceps and four cases of rotator cuff reconstruction, including one patient who underwent two such reconstructions.

The preoperative phase included clinical diagnostics as well as imaging with conventional X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound. Common to all patients was therapy-resistant pain at rest and during movement as well as night time pain.

Furthermore, 22 of the patients displayed a painful loss of joint function with a positive external rotation lag sign, which is given when patients are unable to keep their arm in a previously passively rotated position. Additionally, four patients displayed a positive drop arm sign, which is given when the patient cannot hold a passively positioned arm at 90° abduction.

The criteria for inclusion in the study were unsatisfactory conservative therapy for at least six months with regularly executed physical therapy and non-steroidal anti-rheumatic (NSAR) medication.

The MRI scans of all patients showed a massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tear with involvement of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus and a third-degree retraction of the supraspinatus according to the Patte classification [14]. Furthermore, all patients displayed a fatty degeneration of the infraspinatus in the sagittal and paracoronal planes. A simple muscular atrophy of the supraspinatus according to the Thomazeau classification [15] was not a sufficient indication, as such cases can often be treated by anatomical reconstruction. Another criterion of inclusion was an intact subscapularis, demonstrated both clinically and by means of MRI.

Surgical technique

The patient was placed in a lateral decubitus position. Patients without previous arthroscopy with tenotomy or tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon received arthroscopy of the shoulder joint, while those with tendinitis, instability or partial tears received an arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps tendon.

The transfer of the tendon begins with a straight incision, beginning about 5 cm below the posterolateral edge of the acromion following the triceps for about 6–8 cm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a–c A 53-year-old patient with a massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tear, lateral decubitus position. The surgical approach was carried out reaching from the posterior deltoid approximately 5 cm below the posterolateral edge of the acromion along the triceps: a, b show the raised muscle belly of the latissimus dorsi and teres major during the operation. Please note the dorsal arthroscopy portal “loco typico”. c Intraoperative view after refixation of the tendon

The latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons were identified and the axillary nerve was displayed. The tendons were sharply dissected from the humerus while taking care to avoid damage to the radial nerve. In those cases in which separation from the teres major tendon is not possible, a combined transfer is necessary. Subsequently, one locates the previous insertion site of the infraspinatus muscle at the greater tuberosity using the same surgical access. A bony trough was prepared in abduction and external rotation at the previous insertion site of the infraspinatus muscle. After insertion of suture anchors the tendons were attached using Mersilene 2 with a Mason-Allen suture technique. Respecting the integrity of the muscle, a passage was bluntly developed underneath the posterior part of the deltoid in order to reach the insertion zone of the infraspinatus. Finally the vitality and stability were tested.

Postoperative treatment

Immediately after surgery the arm is rested on an abduction pillow for three weeks. During this period passive mobilisation was restricted to 30° abduction, 30° flexion, or in internal rotation of 60° or in neutral rotation of 0°. The range of motion was increased to 60° abduction, 90° flexion and 60° internal rotation up to the end of week six. Depending on pain a free range of motion was allowed with careful strengthening after the seventh week when the passive mobilisation was free.

Follow-up evaluation

The follow-up was performed after 24 months (range: 12–41 months, n = 26). The patients were clinically evaluated using the age- and gender-adjusted scoring system of Constant and Murley.

Standard radiography was attempted consisting of a true anteroposterior, an outlet and an axillary view.

The acromiohumeral distance was measured in the true anteroposterior view. The grade of glenohumeral osteoarthritis and cuff tear arthropathy was detected using the classification according to Hamada et al. [16]. The integrity of the muscular flap was examined either by ultrasound or in 14 cases through additional MRI.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SAS (SAS reverse 0.8). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Pre- and postoperative nonparametric data from both groups were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

The mean Constant score increased significantly (p < 0.0001) from initially 20 points (range: 13.0–34 points; adjusted Constant score: 26, range: 14–42) to 56 points (range: 23.0–81.0 points; adjusted Constant score: 70, range: 27.0–98.0 points) two years postoperatively. The patients showed a significant (p < 0.0001) improvement in all qualities including pain, activities of daily living and active range of motion. Even though significant, the strength of abduction increased merely from 0 to 1.8 points.

The implemented pain score ranging from 0 to 15 showed a significant improvement from a preoperative average of 5 to postoperative average of 11.8. The evaluation of the range of motion showed a significant increase from 10.3 to 27.9. With regard to the activities of daily living the Constant score increased from 5.3 to 14.2 points.

Of the 26 patients, 22 (85%) were also subjectively content with the results (Fig. 2). Prior to surgery 85% of the patients had a positive external rotation lag sign, which could be demonstrated in 19% after two years. A positive drop arm sign was seen in 15.4% of the patients preoperatively which resolved postoperatively in all.

Fig. 2.

a–c The same patient 12 months postoperatively demonstrating near normal shoulder joint range of motion

Imaging

Analysis of the radiographs showed preoperatively a acromiohumeral distance of 4.7 mm (range: 1–9 mm), which remained statistically unchanged at 4.8 mm (range: 2–11 mm) after two years.

Before surgery 46% of the patients had a cuff tear arthropathy: 11.5% a grade 1 and 34.5% a grade 2 according to the classification of Hamada. Each cohort increased one level from 1 to 2 and from 2 to 3 by the time of the two-year follow-up.

Nevertheless, the increase in osteoarthritis was not associated with a reduction of shoulder function as seen in a persistent Constant score.

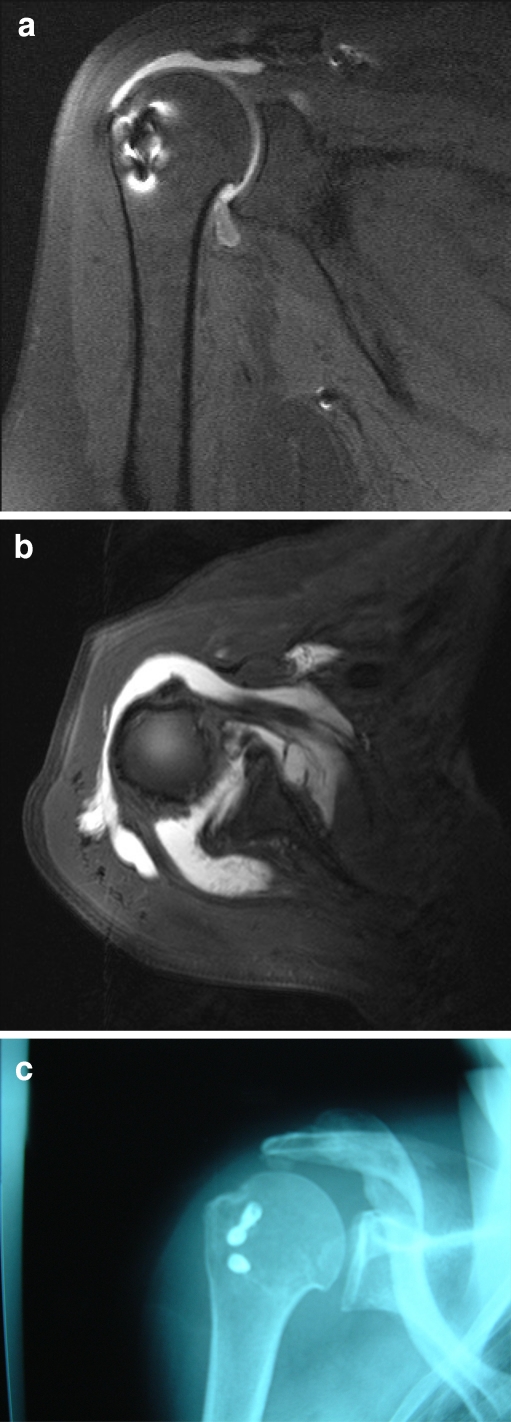

MRI (n = 14) showed consistent integrity of the latissimus dorsi and teres major flap at two years follow-up and in one case a rerupture of the reinserted latissimus dorsi tendon (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a, b Postoperative MRI with the placement of the suture anchor and the insertion of the latissimus dorsi tendon in a transverse and coronal plane. c Anteroposterior X-ray with the suture anchors at the insertion zone of the infraspinatus tendon

In one case the suture anchor failed on the second postoperative day. This was immediately reattached using transosseous refixation. The average time required for surgery was 54 min (42–102 min).

Discussion

Since its introduction by Gerber in 1988, the latissimus dorsi transfer has become an established surgical option for non-reconstructable, massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. The first systematic postoperative examination followed in 1992 and showed preliminary clinical results in over 16 patients with a 33-month follow-up. This study revealed good results with the age-adapted Constant score showing 75% [1, 2]. Other working groups have also reported similar positive results [17–21]. The largest study up till now was Gerber’s in 2006; 69 patients were examined in a follow-up examination with an average of 53 postoperative weeks. The Constant score in this collective increased from a preoperative value of 46 up to 60 at the time of the final follow-up examination [3].

The observations resulting from the modified Herzberg technique showed results comparable to other techniques in the literature in the first follow-up examinations.

Gohlke et al. examined 90% of their patients by MRI six years after surgery and discovered that the transferred muscle had grown in size, an indirect sign of muscle activity. Nonetheless, their main purpose of these MRI scans was to examine the integrity of the tendon reimplantation and to show the quality, safety and long-term results of this new technique by means of imaging.

Several authors have attempted to find sensible predictive factors which have an influence on the postoperative outcome. For example, Werner et al. focused on the function of the subscapularis and consider this muscle’s integrity to be a vital prerequisite for good clinical results [22]. We also view an intact subscapularis muscle to be a fundamental prerequisite in the indication for an operation. Consequently, all patients included in this study showed a preoperatively intact muscle on MRI scans.

Other studies have focused on the teres minor and have shown that this muscle’s integrity is a predictive factor for a positive outcome [23]. It remains uncertain if the number of previous operations in the shoulder joint is a relevant factor. While Warner and Pearson [20] demonstrated significantly poorer results in previously operated shoulders, Miniaci and MacLeod did not [19].

Irlenbusch et al. [17] also showed inferior results in the group with revisions. Our study only included eight cases who had undergone previous operations, which is too small a sample size to make any kind of sensible analysis. However, one ought to generally make a distinction between an arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps tendon or an unsuccessful open operative reconstruction of the rotator cuff.

Other factors affecting the outcome had to be considered, such as a previous osteoarthritis, which obviously limits expectations, especially in the long run. It does not seem very plausible to expect a muscle transfer to positively influence pain caused by arthritis.

The limitations of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer include weakness of abduction, because a muscle transfer alone may not restore active abduction and is contraindicated in cases of associated advanced osteoarthritis which can addressed by a reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer as recently shown by Gerber et al. [12] and Boileau et al. [13]. In elderly patients especially and in cases with concomitant subscapularis insufficiency reverse total shoulder arthroplasty is a treatment option due to the fact that the latissimus dorsi transfer has not been observed to increase internal rotator weakness.

However, the positive drop arm sign, which was seen in 15.4% of the patients preoperatively, resolved postoperatively in all cases; nonetheless, the strength of the patients did not improve. Although external rotation deficit and drop arm sign can be successfully treated with a tendon transfer, such a muscle transfer alone may be inadequate to enhance the strength of external rotation and elevation against resistance.

In our study, the presence of early osteoarthritis was not associated with a reduction of shoulder function. Of the 26 patients in this study, nine had X-rays displaying Hamada grade 2 preoperatively. Whether or not these individuals will have a worse outcome can only be shown in the course of time. Nonetheless, they do not have inferior results as of yet.

Iannotti et al. [18] came to the conclusion that the preoperative range of motion is a significant factor in determining the postoperative outcome, since the shoulder may go from weak to worse through the transfer of an already weakened muscle.

Each additional trauma to a weak deltoid muscle or compromise of the coracohumeral arch can lead to a worse result. In this regard Gumina et al. described deltoid detachment as one of the most common complications [24]. Otherwise, good to excellent results are described in a long-term follow-up of over ten years in patients treated by a deltoid flap reconstruction [25]. However, it should be borne in mind that other techniques are possible without detachment of the deltoid muscle.

It is on the basis of this consideration that Habermeyer modified the L’Episcopo transfer—often implemented following plexus lesions occurring during birth—for use in non-reconstructable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. With an average follow-up of 70 months, these findings are comparable with published results.

Herzberg et al. were able to show superior rotation movement of the arms following the insertion of the latissimus dorsi at the site of the infraspinatus at the greater tuberosity across from the insertion site of the supraspinatus [9].

Habermeyer et al. consider a major benefit of the single-incision technique to be abandonment of the need for transacromial access with a detachment of the deltoid. In contrast to Habermeyer et al.’s [11] single-incision technique published in 2006, we specifically opted not to expand the operative access to include the latissimus dorsi muscle and to release the muscle from there. Our access is limited to clearly showing the humeral tendon origin and the site of reinsertion. This has the potential drawback that the origins of latissimus dorsi and teres major may not always be cleanly isolated and separated. On the other hand, a potential benefit lies in the minimal time and effort required during the operation. The operations in this study required an average of 54 minutes. Furthermore, one can directly work towards the humeral shaft lateral to the long head of triceps, and there is no danger of damaging the axillary nerve.

Clinical examinations directly comparing the reinsertion at the previous infraspinatus or supraspinatus insertion site do not exist as of yet.

Following the increase of the acromiohumeral distance in the first two years of this study, this recentralising effect will most likely be lost and the osteoarthritis will increase—as shown by other working groups.

Aside from biomechanical factors, progression of osteoarthritis must be viewed as a multifactorial process. Similarly, pre-existing damage definitely shows progression, as has been confirmed by Gerber and in this study.

This study shows that, on the basis of preliminary results and the low morbidity of the operation, latissimus dorsi transfer in the modified Herzberg technique is a sensible alternative to the technique initially described by Gerber. It could not be shown that this is a superior method. Following the clinical observations, it is now possible to carry out a randomised prospective comparison.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celli L, Rovesta C, Marongiu MC, Manzieri S. Transplantation of teres major muscle for infraspinatus muscle in irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:485–490. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augereau B, Apoil A. Repair using a deltoid flap of an extensive loss of substance of the rotary cuff of the shoulder (in French) Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1988;74:298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito J, Morioka T. Surgical treatment for large and massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2003;27:228–231. doi: 10.1007/s00264-003-0459-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Lichtenberg S (2002) The modified L’Episcopo procedure to reconstruct masive rotator cuff tears—a prospective study. AAOS Congress 2002

- 8.Beauchamp M, Beaton DE, Barnhill TA, Mackay M, Richards RR. Functional outcome after the L’Episcopo procedure. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:90–96. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzberg G, Urien JP, Dimnet J. Potential excursion and relative tension of muscles in the shoulder girdle: relevance to tendon transfers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:430–437. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(99)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoierer O, Herzberg G, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J, Aswad R, Morin A. Anatomical basis of latissimus dorsi and teres major transfers in rotator cuff tear surgery with particular reference to the neurovascular pedicles. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23:75–80. doi: 10.1007/s00276-001-0075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Rudolph T, Lichtenberg S, Liem D. Transfer of the tendon of latissimus dorsi for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff: a new single-incision technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:208–212. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Lingenfelter EJ, Sukthankar A. Reverse Delta-III total shoulder replacement combined with latissimus dorsi transfer. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:940–947. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Bicknell RT, Rochet N, Trojani C. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a modified latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer for shoulder pseudoparalysis associated with dropping arm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:584–593. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patte D. Classification of rotator cuff lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomazeau H, Rolland Y, Lucas C, Duval JM, Langlais F. Atrophy of the supraspinatus belly. Assessment by MRI in 55 patients with rotator cuff pathology. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:264–268. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irlenbusch U, Bensdorf M, Gansen HK, Lorenz U. Latissimus dorsi transfer in case of irreparable rotator cuff tear–a comparative analysis of primary and failed rotator cuff surgery, in dependence of deficiency grade and additional lesions (in German) Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141:650–656. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iannotti JP, Hennigan S, Herzog R, Kella S, Kelley M, Leggin B, Williams GR. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:342–348. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miniaci A, MacLeod M. Transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle after failed repair of a massive tear of the rotator cuff. A two to five-year review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1120–1127. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner JJ, Parsons IM., 4th Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer: a comparative analysis of primary and salvage reconstruction of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:514–521. doi: 10.1067/mse.2001.118629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zafra M, Carpintero P, Carrasco C. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2009;33:457–462. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0536-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner CM, Zingg PO, Lie D, Jacob HA, Gerber C. The biomechanical role of the subscapularis in latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:736–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costouros JG, Espinosa N, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Teres minor integrity predicts outcome of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumina S, Giorgio G, Perugia D, Postacchini F. Deltoid detachment consequent to open surgical repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Int Orthop. 2008;32:81–84. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandenbussche E, Bensaida M, Mutschler C, Dart T, Augereau B. Massive tears of the rotator cuff treated with a deltoid flap. Int Orthop. 2004;28:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]