Abstract

To evaluate the outcome of the excisional surgeries (en bloc/debulking) in spinal metastatic treatment in 10 years. A total of 131 patients (134 lesions) with spinal metastases were studied. The postoperative survival time and the local recurrence rate were calculated statistically. The comparison of the two procedures on the survival time, local recurrence rate, and neurologic change were made. The median survival time of the en bloc surgery and the debulking surgery was 40.93 and 24.73 months, respectively, with no significant difference. The significant difference was shown in the local recurrence rate comparison, but not in neurological change comparison. 19.85% patients combined with surgical complications. The en bloc surgery can achieve a lower local recurrence rate than the debulking surgery, while was similar in survival outcome, neurological salvage, and incidence of complications. The risk of the excisional surgeries is high, however, good outcomes could be expected.

Keywords: Spinal metastasis, Surgical treatment, Prognosis

Introduction

In the past, the aims of surgery for spinal metastases were largely confined in decompression for the compressed spinal cord and/or nerve roots [4, 7, 17]. Other common indications for surgery include intractable pain, pathologic fracture, and spinal instability caused by the lesion [8]. Laminectomy, the most frequently adopted traditional procedure in early time, has been proved to be mediocre in outcome and not more beneficial than radiotherapy alone [3, 25]. Due to the improvement of the surgical techniques, more and more aggressive surgeries were adopted in spinal metastatic treatment [11, 18, 22]. Nowadays, the superiority of surgery in management of spinal metastases has been supported by a number of documentaries, in spite of the long-existing controversies [9, 11, 15].

We have performed excisional en bloc and debulking surgeries in selected spinal metastatic cases since more than 10 years ago. We conducted this retrospective study to evaluate the outcome of excisional surgeries for the patients with spinal metastases in duration of 10 years.

Materials and methods

During the time from January 1997 to December 2006, 157 spinal metastatic patients with 167 lesions were treated primarily with en bloc/debulking surgeries at the orthopedic and traumatology department of the Ospedale Maggiore, Bologna. There were 93 of male and 64 of female. The average age of the patients was 57 (range 20–79) years. Due to variable reasons, 26 patients failed in postoperative follow-ups. There were 131 patients with 134 treated lesions followed up with duration of at least 6 months except for the patients dead during the time of follow-up and these cases were all included in this study. Among these patients, there were 26 patients with 28 metastatic lesions located in the cervical spine, 52 patients with 53 lesions in the thoracic spine, and 53 patients with 53 lesions in the lumbar spine. The metastases of sacrum and coccyx were excluded in this study because of the particular anatomy in these sites. Pathologic fractures were found in 36 lesions and non-spinal skeletal metastases in 14 patients, lung metastases in 14 patients, liver metastases in 4 patients, and cerebral metastases in 2 patients. A clear diagnosis was made in 110 lesions before the operations with 65 lesions diagnosed after a CT-guided trocar biopsy. In other cases, four lesions were diagnosed after an open biopsy and four lesions after surgery. And 16 lesions were pathologically examined to be metastatic tissues without definite histological diagnoses. The profiles of the primary tumors (lesions) were listed in Table 1. The multiple myeloma and lymphoma were excluded in the understanding that these were parts of special systemic diseases rather than metastases from primary tumors. The kidney, lung, and breast accounted for the three most primary lesions with percentages of 32.84, 14.93, and 12.69%, respectively.

Table 1.

Profile of primary lesions

| Primary lesions | No. of lesions | |

|---|---|---|

| En bloc | Debulking | |

| Kidney | 19 | 25 |

| Lung | 2 | 18 |

| Breast | 1 | 16 |

| Unkown | 3 | 13 |

| Thyroid | 1 | 7 |

| Colon | 0 | 5 |

| Melanoma | 1 | 3 |

| Leiomiosarcoma | 0 | 4 |

| Schwannoma | 2 | 0 |

| Pancreas | 0 | 2 |

| Uterus | 0 | 2 |

| Bladder | 0 | 1 |

| Cordoma | 0 | 1 |

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 1 | 0 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 | 0 |

| Intestine | 0 | 1 |

| Liposarcoma | 0 | 1 |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 0 |

| Prostate | 0 | 1 |

| Rectum | 0 | 1 |

| Testis | 0 | 1 |

Significant difference was found in the statistical comparison between the histology breakdowns of the two groups (Chi-square = 3.35, P = 0.02)

The neurologic statuses of the patients were also evaluated preoperatively according to the Frankel scale system. There were 87 patients evaluated Frankel E who were neurologically intact. And 73 patients were Frankel D, among whom 11 patients were scaled Frankel D3, 8 patients Frankel D2, and 12 patients Frankel D1. The seriously neurologically impaired cases included 10 Frankel C, 2 Frankel B, and 1 Frankel A.

All the patients were subject to en bloc or debulking surgeries after evaluated to be operable by anesthetists. The management patterns were determined according to the algorithm developed by us [9]. The option of whether the debulking or en bloc resection to be performed was decided mainly on the possibility of en bloc surgeries according to WBB staging system [5, 6]. Highly vascularized tumors like metastases from kidney were preferred to en bloc resection. Three en bloc resection methods were performed according to the WBB staging system as vertebrectomy (en bloc resection of the vertebral body), sagittal resection (en bloc resection of combined part the vertebral body and part of the posterior arch), and resection of the posterior arch. Some lesions might undergo more than one operation because of local recurrence, but the subsequent surgeries were always palliative and not considered as an important factor in this study.

The radiological re-examinations including X-ray, CT scan, and/or MRI were taken and evaluated for changes of the treated segments and lesions in other sites periodically for all the patients after treatment. For each lesion, the occurrence of local recurrence was investigated and recorded at follow-up. Meanwhile the postoperative Frankel scale and surgical complications were also recorded for every patient.

Statistical analysis was performed to compare the pre- and postoperative Frankel scales of the patients using Wilcoxon signed ranks test. The postoperative survival time and the cumulative local recurrence rate of the patients were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method or 1 minus Kaplan–Meier method. The comparison of survival time and local recurrence rate between the two procedures was made by Log-Rank method. The comparison of incidence of complications was made by Chi-square test. Other comparisons of numerical variables were made by t test. P value <0.05 (two tailed) was considered significant.

Results

In the cases included in this study, 32 patients with 32 lesions received the primary procedures of en bloc surgery and 99 patients with 102 lesions were primarily subject to surgeries of debulking. Of the en bloc surgeries, there were 26 cases of vertebrectomy, 3 of sagittal resection, and 3 of posterior resection. Forty-six lesions received preoperative selective artery embolization. A total of 110 patients (83.97%) received preoperative or/and postoperative adjuvant therapies (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, etc).

The mean operative time and blood loss in the en bloc surgeries were 7.67 h and 1536.56 ml, respectively, while the mean operative time and blood loss in the debulking surgeries were 4.32 h and 954.22 ml, respectively. Both the operative time and the blood loss were significantly different between the two groups (t = −7.20, P < 0.01; t = −4.10, P < 0.01).

There was no patient dead during the operation in this study. And 2 patients (1.53%) including 1 patient of debulking surgery and 1 of en bloc surgery died within 1 month after operation. There were totally 12 patients (9.16%) dead within 6 months after operation. The median postoperative follow-up time was 18.53 months. There were 71 patients dead and 60 patients alive until the latest follow-ups. The median postoperative survival time in the whole was 26.67 ± 2.44 (95% confidence interval: 21.90–31.44) months, calculated statistically by Kaplan–Meier method. The survival plot is shown in Fig. 1. The plot showed an expected high survival possibility of 20% even after 10 years (120 months). At the same time, the median survival time was calculated, respectively, and compared according to two different surgical procedures. The median survival time of the debulking surgery was 24.73 ± 3.49 (17.90–31.56) months and that of the en bloc surgery seemed even longer, which was 40.93 ± 12.72 (16.00–65.86) months. However, there was no significant difference (Chi-square = 1.32, P = 0.25) shown in the comparison of survival time between the two different procedures. The two survival plots are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curve

Fig. 2.

Survival curves of the two surgeries

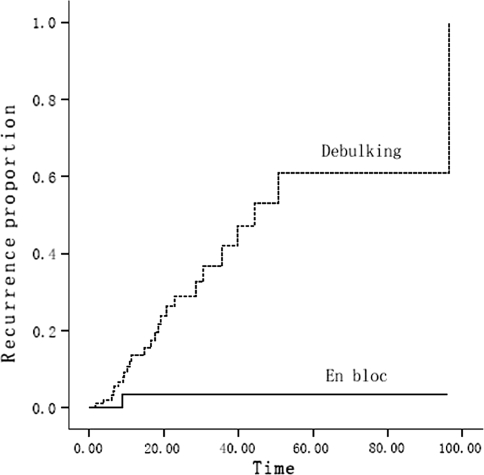

There were 26 lesions suffered from local recurrences accounting for 19.85% of all the cases followed up. The cumulative local recurrences were analyzed by 1 minus Kaplan–Meier method and the comparison between the two different procedures was made further by Log-Rank method. The time of recurrence was the duration from the date of operation to the diagnosis of recurrence at first time (because a few lesions underwent recurrence more than one time). The curves of the cumulative local recurrences are shown in Fig. 3. The significant difference (Chi-square = 8.37, P = 0.004) was shown in the comparison. The plot showed that the local recurrence rate of the en bloc surgery was steadily less than 20% after 20 months, while, that of the debulking surgery was much higher at anytime postoperative and nearly 100% local recurrence was estimated at 100 months after operation.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative local recurrence curves of the two surgeries

There was no difference between the patients’ neurologic functions in the two subgroups according to the statistic comparison of the patients’ preoperative Frankel grades (Z = −1.36, P = 0.17). There were 35 patients (26.72%) whose immediate postoperative neurologic function was improved than preoperative, 93 patients (70.99%) who maintained the neurologic function after operation, and other 3 patients (2.29%) deteriorated in the neurologic status immediately postoperatively. The statistic comparison between the preoperative and the immediate postoperative neurological function of all patients was significant different (Z = −4.55, P < 0.001). In the other hand, there were 8 patients (6.11%) whose latest postoperative neurologic function was better than immediate postoperative and 94 patients (71.76%) whose latest neurologic function was the same as that of immediate postoperation. Other 29 patients (22.14%) whose neurologic function got worse at the postoperative follow-up and among these patients, 6 were caused by the local recurrence, and 2 were relative with the implant failure. The statistic comparison between the immediate postoperative and the latest postoperative neurological function also showed significant difference (Z = −3.93, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the comparisons of changes of either immediate or latest neurological function between the two managements both showed no significant difference (Z = −0.96, P = 0.74; Z = −0.06, P = 0.95).

The surgical complications happened in 26 patients, accounting for 19.85% of all the patients. There were two different complications happened in 6 patients and three complications in 1 patient. The complications were divided to major complications, which were fatal or irreversible illnesses, requiring emergent salvage or surgical management and minor complications, which were usually encountered and reversible illnesses, not necessary for surgical treatment. The profiles of the surgical complications are shown in Table 2. There were 6 patients (18.75%) by en bloc surgery and 13 patients (12.75%) by debulking surgery underwent major complications. And 3 patients (9.38%) by en bloc surgery and 11 patients (11.11%) by debulking surgery had minor complications. The statistic comparison of the two surgical procedures showed no significance either in major complication or in minor complication (Chi-square = 0.62, P = 0.43; Chi-square = 0.08, P = 0.78, respectively).

Table 2.

Profiles of surgical complications

| Complications | En bloc | Debulking |

|---|---|---|

| Major | ||

| Pericardiac tamponade | 0 | 1 |

| Aorta lesion | 1 | 0 |

| Vena cava lesion | 1 | 0 |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 2 |

| Hemothorax | 1 | 0 |

| Paraplegia | 0 | 1 |

| Massive hemorrhage | 1 | 6 |

| Infection under diaphragm | 1 | 0 |

| Laparocele requiring surgery | 0 | 1 |

| Superficial wound infection (requiring surgery) | 1 | 0 |

| Implant failure requiring revision | 0 | 2 |

| Minor | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary infection | 0 | 1 |

| Respiratory dysfunction | 1 | 0 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leakage | 1 | 2 |

| Superficial wound infection (not requiring surgery) | 0 | 3 |

| Superficial wound necrosis (not requiring surgery) | 1 | 3 |

| Asymptomatic implant failure | 0 | 1 |

Case presentations

Case 1

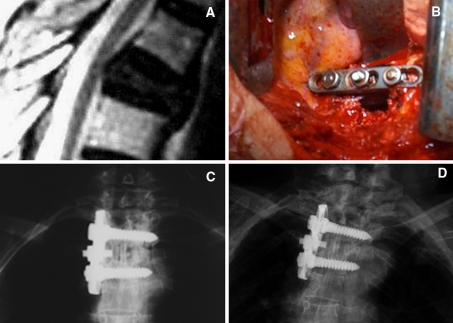

R.L. Female. She was 53-years-old when admission to our department on April 1998 because of back pain. And she received mastectomy because of breast cancer in 1989. Her neurologic function was intact. After workup, an isolated T4 metastatic lesion was found. Then a procedure of debulking with instrumentation through anterior approach was performed. Her back pain relieved and neurologic function maintained immediately after operation. The patients received radiotherapy after operation. She underwent local recurrence 14 months later and was found new lesions of metastasis in other segments, then received vertebroplasty and radiotherapy for many times. However, she was still alive at the latest follow-up and had survived for almost 10 years (119 months) since the primary operation (Fig. 4a–d).

Fig. 4.

a The preoperative T2 weighted MR image. b The photograph during the operation. c The postoperative roentgenogram. d The roentgenogram 8 years after surgery

Case 2

R.M. Female. She was 64-years-old when admission to our department on June 2000 because of incomplete paraplegia. She received nephrectomy because of renal cell carcinoma in 1998. Her preoperative Frankel scale was evaluated to be “C”. An isolated T5 metastatic lesion was found and the spinal cord had been compressed by the invasion of the lesion. An en bloc surgery of sagittal resection through posterior approach with transpedicular instrumentation plus reconstruction with mesh in emergency was performed for her. Immediately after the operation her neurologic function recovered to Frankel E. She received postoperative radiotherapy. She had maintained neurologic function and had survived continuously disease free for 95 months before the latest follow-up (Fig. 5a–e)

Fig. 5.

a The preoperative CT scan. b The roentgenogram of the specimen. c The postoperative CT scan. d The postoperative roentgenogram. e The CT scan 5 years after surgery

Discussion

Nowadays, the management of spinal metastases should still be a multidisciplinary collaboration. The treatment for spinal metastases is a synthesis of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immune therapy, and other applicable conservative treatments. At the same time, surgical treatments have been evaluated to be important and effective in some recent studies [11, 13, 14].

Many new surgical concepts and procedures for management of the spine tumor have been greatly developed in recent years. These developments made the spinal metastatic treatments more safe and effective. Tomita et al. [21] designed the special surgical procedure so-called total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) and used it on the spinal metastatic cases with a quite good outcome [22]. Although the WBB surgical staging system was initially designed for primary spine tumors [6], we successfully utilized this system in planning for the en bloc surgery of spinal metastases.

The survival outcomes of debulking and en bloc surgeries in treatment of spinal metastatic diseases were variable, but mostly seem desirable. The survival outcomes of the literatures are presented in Table 3. It can be seen that the median/mean survival of the en bloc surgeries always achieved good survival outcomes, which varied from more than 1 year to more than 3 years. While the debulking surgeries were mostly more than 1 year, but not as good as more than 2 years. In our study, the median postoperative survival time of the patients after en bloc or debulking surgeries was also very exciting, which was longer than 2 years. Although no significant difference was found in the comparison of survival time between the two procedures, the en bloc surgery showed a longer median survival time than the debulking surgery, which was also concluded by Ibrahim et al. [11] through an international multicenter prospective observational study.

Table 3.

Survival outcomes of excisional surgeries

| Techniques | References | Procedures | Series | Survival outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| En bloc | Tomita et al. [23] | Total en bloc spondylectomy (posterior approach) | 24 patients with thoracolumbar spine metastases | 12 patients (50%) survived after a median follow-up period of 14.1 months |

| Akeyson et al. [1] | Vertebrectomy (posterior approach) | 25 patients with thoracolumbar spine metastases | Mean survival after surgery was 29.5 ± 8.2 weeks | |

| Tomita et al. [22] | Total en bloc spondylectomy (posterior approach) | 28 patients with spinal metastases | Mean survival was 38.2 months | |

| Sakaura et al. [16] | Total en bloc spondylectomy (posterior approach) | 12 patients with solitary spinal metastases | 7 have survived for an average of 61 months, 5 died with a mean survival of 23 months after surgery | |

| Ibrahim et al. [11] | En bloc surgery (anterior/posterior approach) | 28% of 223 patients with spinal metastases | Median survival was 18.8 months | |

| Debulking | Timlin et al. [19] | Intralesional excision (anterior approach/combined anterior-posterior approach) | 28 patients with thoracolumbar spine metastases | Postoperative survivorship was an average of 6.4 months |

| Walsh et al. [24] | Anterior resections (anterior approach) | 61 patients with thoracic spine metastases | 1-year cumulative survival for the entire group was 60% | |

| Gokaslan et al. [10] | Transthoracic vertebrectomy (anterior approach) | 72 patients with spine metastases involved thoracic spine | 1-year survival rate for the entire study population was 62% | |

| Tomita et al. [22] | Intralesional excision (posterior approach) | 13 patients with spinal metastases | Mean survival was 21.5 months | |

| Ibrahim et al. [11] | Intralesional excision (anterior/posterior approach) | 46% of 223 patients with spinal metastases | Median survival was 13.4 months |

Furthermore, the cumulative local recurrence rate of the en bloc was calculated to be much lower than the debulking. Because the en bloc surgery is a highly demanding technique, we always discussed and planned carefully before the operation. Much indebted to the existed WBB surgical staging system [5, 6], we could efficiently design the operations and appropriately determine the surgical margins. Therefore, the en bloc surgery achieved the outcome as expected and effectively avoided local recurrence in most cases. And the postoperative neurologic function changes of the patients showed that the neurologic function of most patients could be salvaged or maintained immediately after operation, but many deteriorated later. The statistic results also showed that the debulking and the en bloc surgery were equally effective in the neurologic function salvage.

It also should be admitted that the aggressive surgeries for treatment of spinal metastases are very demanding and risky. The risks include neurologic deterioration, excessive bleeding, healthy tissue contamination, etc., that may weaken the immune system, cause infection, speed the metastatic process, and even lead to direct death. It can be seen in the study that the operative time were always long and the blood loss were frequently substantial in the excisional surgeries. The differences of operative time and blood loss between the two subgroups noted that the en bloc surgeries were even more risky than the debulking surgeries. Furthermore, in excisional surgeries, early mortality is high, with a 6-month mortality rate of up to 50% according to some studies [2, 12], and both of the excisional surgical procedures have a high incidence of complications. Although in our study, the mortality in the perioperative period (9.16%) was not high, the incidence of surgical complications was as high as nearly 20%. So the doctors should weigh the benefits and the risks carefully before submitting a patient to en bloc/debulking surgeries, in the other hand, the excisional surgeries should be performed by experienced doctors.

In order to achieve the best outcome, it is crucial to select the primary treatment exactly for the spinal metastases. The already existed scoring systems could help in the selection of the reasonable treatment [20, 22]. However, we did not indicate surgeries merely on these scoring systems. Instead, a step-by-step judgment process was adopted in our clinical practice [9]. The desirable outcome of the excisional surgeries, to some extent, validated the effectiveness of our treatment algorithm.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carlo Piovani for his graphic support.

Contributor Information

Haomiao Li, Email: hamsli@sohu.com.

Alessandro Gasbarrini, Phone: +39-328-8424400, FAX: +39-051-6478948, Email: alessandro.gasbarrini@yahoo.com, Email: boova@libero.it.

Stefano Boriani, Email: stefanoboriani@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Akeyson EW, McCutcheon IE. Single-stage posterior vertebrectomy and replacement combined with posterior instrumentation for spinal metastasis. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:211–220. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.2.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argenson C, Cordonnier D, Enkaoua E, Laredo JD, Onimus M, Resbeut M, Alzieu C, Hannounn-Levi JM, Noirclerc M, Cowen D (1997) Place de la chirurgie dans la traitement des me′ tastases du rachis. SOF. COT Reunion Annuelle, Novembre 1996. Rev Chir Orthop 83(suppl):109–174

- 3.Bednar DA, Brox WT, Viviani GR. Surgical palliation of spinal oncologic disease: a review and analysis of current approaches. Can J Surg. 1991;34:129–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benzel EC. The lateral extracavitary approach to the spine using the three-quarter prone position. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:837–841. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.6.0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boriani S, Weinstein JN (1997) Differential diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary benign and malignant neoplasms. In: Frymoyer JW (ed). The adult spine: principles and practice, 2nd edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

- 6.Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine. 1997;22:1036–1044. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne TN. Spinal cord compression from epidural metastases. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:614–619. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208273270907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWald RL, Bridwell KH, Prodromas C, Rodts MF. Reconstructive spinal surgery as palliation for metastatic malignancies of the spine. Spine. 1985;10:21–26. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Mirabile L, Bandiera S, Terzi S, Barbanti Bròdano G, Boriani S. Spinal metastases: treatment evaluation algorithm. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2004;8:265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gokaslan ZL, York JE, Walsh GL, McCutcheon IE, Lang FF, Putnam JB, Jr, Wildrick DM, Swisher SG, Abi-Said D, Sawaya R. Transthoracic vertebrectomy for metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:599–609. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim A, Crockard A, Antonietti P, Boriani S, Gasbarrini A, Grejs A, Harms J, Kawahara N, Mazel C, Melcher R, Tomita K (2008) Does spinal surgery improve the quality of life for those with extradural (spinal) osseous metastases? An international multicenter prospective observational study of 223 patients. Invited submission from the joint section meeting on disorders of the spine and peripheral nerves, March 2007. J Neurosurg Spine 8:271–278 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Klekamp J, Samii H. Surgical results for spinal metastases. Acta Neurochir. 1998;140:957–967. doi: 10.1007/s007010050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klimo P, Jr, Thompson CJ, Kestle JR, Schmidt MH. A meta-analysis of surgery versus conventional radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic spinal epidural disease. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:64–76. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liljenqvist U, Lerner T, Halm H, Buerger H, Gosheger G, Winkelmann W. En bloc spondylectomy in malignant tumors of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:600–609. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryken TC, Eichholze KM, Gerszten PC, Welch WC, Gokaslan ZL, Resnick DK. Evidence-based review of the surgical management of vertebral column metastatic disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaura H, Hosono N, Mukai Y, Ishii T, Yonenobu K, Yoshikawa H. Outcome of total en bloc spondylectomy for solitary metastasis of the thoracolumbar spine. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:297–300. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000096269.75373.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundaresan N, Digiancinto GV, Hughes JE, Cafferty M, Vallejo A. Treatment of neoplastic spinal cord compression: results of a prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:645–650. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundaresan N, Rothman A, Manhart K, Kelliher K. Surgery for solitary metastases of the spine. Rationale and results of the treatment. Spine. 2002;27:1802–1806. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timlin M, Thalgott J, Ameriks J, Jordan F, Kabins M, Gardner V, Fritts K. Management of metastatic tumors to the spine using simple plate fixation. Am Surg. 1995;61:704–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Oda H, Oshima M, Ryu J. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine. 2005;19:2186–2191. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180401.06919.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, Tsuchiya H, Fujita T, Toribatake Y. Total en bloc spondylectomy: a new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine. 1997;22:324–333. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Kobayashi T, Yoshida A, Murakami H, Akamaru T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine. 2001;26:298–306. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200102010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomita K, Toribatake Y, Kawahara N, Ohnari H, Kose H. Total en bloc spondylectomy and circumspinal decompression for solitary spinal metastasis. Paraplegia. 1994;32:36–46. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh GL, Gokaslan ZL, McCutcheon IE, Mineo MT, Yasko AW, Swisher SG, Schrump DS, Nesbitt JC, Putnam JB, Jr, Roth JA. Anterior approaches to the thoracic spine in patients with cancer: indications and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1611–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)01034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young RF, Post EM, King GA. Treatment of spinal epidural metastases: randomized prospective comparison of laminectomy and radiotherapy. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:741–748. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.6.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]