Abstract

In order to better understand and elucidate the major determinants of red and white muscle phenotypic properties, the global gene expression profiling was performed in white (longissimus doris) and red (soleus) skeletal muscle of Chinese Meishan pigs using the Affymetrix Porcine Genechip. 550 transcripts at least 1.5-fold difference were identified at p < 0.05 level, with 323 showing increased expression and 227 decreased expression in red muscle. Quantitative real-time PCR validated the differential expression of eleven genes (α-Actin, ART3, GATA-6, HMOX1, HSP, MYBPH, OCA2, SLC12A4, TGFB1, TGFB3 and TNX). Twenty eight signaling pathways including ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, TGF-beta signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, mTOR signaling pathway, insulin signaling pathway and cell cycle, were identified using KEGG pathway database. Our findings demonstrate previously unrecognized changes in gene transcription between red and white muscle, and some potential cascades identified in the study merit further investigation.

Keywords: Affymetrix, Differential transcriptional analysis, Longissimus doris, Pig, Soleus

1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle is the most abundant human tissue comprising almost 50% of the total body mass, exhibiting major metabolic activity by contributing up to 40% of the resting metabolic rate in adults and serving as the largest body protein pool 1. Skeletal muscle is a very heterogeneous tissue that is composed of a large variety of functionally diverse fiber types 2. Traditionally, skeletal muscle can be distinguished as red (type I and IIa) and white (type IIb) fibers. Red skeletal muscles, such as the soleus and psoas in the pig, have a higher percentage of capillaries, myoglobin, lipids and mitochondria than white skeletal muscles such as the gastrocnemius and longissimus doris 3. In meat animal production, favorable meat traits such as color and, in the pig in particular, tenderness have been found to closely associate with the greater abundance of red or highly oxidative fibres 4-9. In addition, individuals with muscles that are abundant in oxidative type I fibres are associated with favorable metabolic health, and are less likely to predispose to obesity and insulin resistance 10. Collectively, understanding the molecular processes that govern the expression of specific fiber types and the phenotypic characteristics of muscles is very important in agricultural and medical fields.

Microarray technology can simultaneously measure the differential expression of a large number of genes in a given tissue and may identify the genes responsible for the relevant phenotype 11. Campbell et al. identified 49 differentially expressed mRNA sequences between the white quad (white muscle) and the red soleus muscle (mixed red muscle) of female mice using Affymetrix Mu11K SubB containing 6516 probe sets 12. Bai et al. profiled the differential expression of genes between the psoas (red muscle) and the longissimus dorsi (white muscle) of a 22-week-old Berkshire pig using porcine skeletal muscle cDNA microarray comprising 5500 clones 13. The tremendous rise in porcine transcriptomic data has occurred with the development of pig cDNA microarray in the past decade. The Affymetrix porcine genome array showed particularly superior performance for swine transcriptomics 14. In this study, a genome-wide investigation of the porcine differential expression between red (soleus) and white (longissimus dorsi) muscle was conducted using the Affymetrix GeneChip® Porcine Genome Array containing oligonucleotides representing approximately 23937 transcripts from 20201 porcine genes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and tissue sampling

Three Meishan gilts from the same litter were slaughtered at 150 days by electrical stunning and exsanguination, in compliance with national regulations applied in commercial slaughtering. Immediately after slaughter, two muscles with different locations, functions, and biochemical properties were sampled: the longissimus doris at the last rib level, a fast twitch glycolytic muscle involved in voluntary movements of the back, and the deep portion of the soleus, a oxidative muscle. Samples were frozen by liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80℃ until further analysis.

2.2 Total RNA preparation and microarray hybridization

Six microarrays were used in the experiment, corresponding to the RNAs from longissimus doris and soleus of three sibling gilts. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty micrograms total RNA was suspended in RNase-free water with a final concentration of 1.5μg/μl. The RNA labelling and Affymetrix Gene Chip microarray hybridization were conducted according to the Affymetrix Expression Analysis Technical Manual (CapitalBio Corporation, Beijing, China). Array scanning and data extraction were carried out following the standard protocol.

2.3 Identification and bioinformatic analyses of differentially expressed transcripts

The probe-pair (PM-MM) data were used to detect the expression level of transcripts on the array (present call, marginal call, and absent call) by MAS 5.0 (Wilcoxon signed rank test). The signals from the probe pairs were used to determine whether a given gene was expressed and to measure the gene expression level. Raw data from .CEL files were converted to gene signal files by MAS 5.0 (Ver.2.3.1). The expression data from three pigs were loaded into GeneSpring GX 10.0 software (Agilent Technologies) for data normalisation and filtering. Differentially expressed transcripts between longissimus doris and soleus were identified by cutoff of fold-change (FC) ≥ 1.5 and p-value < 0.05 using unpaired t-test. Mean FC is the mean of three biological replicates. Molecular function of differentially expressed genes was classified according to MAS (molecule annotation system) 3.0 (http://bioinfo.capitalbio.com/mas3/). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database were used for signaling pathway analysis on differentially expressed genes. Microarray expression data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, National Center for Biotechnology Information) under accession number GSE19975.

2.4 Quantitative real time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The primer sequences, melting temperature and product sizes of analyzed genes were shown in Table 1. The correct fragment sizes of the PCR products were confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5%). Each primer set amplified a single product as indicated by a single peak during melting curve analyses. Both longissimus doris and soleus RNA prepared for microarray were also included for qRT-PCR. Total RNA were treated with DnaseI and reverse transcribed by the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed on the ABI 7300 real-time PCR thermal cycle instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using SYBR® Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd, Japan). The reactions contained 1× SYBR Green real-time PCR Master Mix, 1μl diluted cDNA template and each primer at 200 nM in a 25 μl reaction volume. After an initial denaturation at 95℃ for 3 min amplification was performed with 40 cycles of 95℃ for 15 s, 61℃ for 15 s, 72℃ for 20 s; plate read; melting curve from 55℃ to 95℃, read every 0.2℃, hold for 1 second. For each sample, reactions were set up in triplicate to ensure the reproducibility of the results. At the end of the PCR run, melting curves were generated and analyzed to confirm non-specific amplification, then the mean value of each triplicate was used for further calculation. Gene expression level was quantitated relative to the expression of the reference gene (HPRT: hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase) by employing the 2-△△Ct value models 15. For each gene, the sample with the largest ΔCt value was set as control. The expression data were calculated using the SigmaPlot version 9.0 software (Systat software Inc., USA). Expression difference of target genes between two muscles was analyzed using t-test. The p < 0.05 was deemed to be significant and p < 0.01 highly significant.

Table 1.

Specific primer sequences for qRT-PCR

| Gene symbol | Description | Reference sequence | Primer sequence (5'-3') | Tm (℃) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Actin | α-Actin | Ssc.1901 | F: GATGGCGTAACCCACAAC | 61 | 194 |

| R: AGGGCAACATAGCACAGC | |||||

| FHL1C | Four and a half LIM domains 1 protein, isoform C | Ssc.14463 | F: GCTGTGGAGGACCAGTATTA R: CCAGATTCACGGAGCATT | 61 | 175 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | Ssc.115 | F: CACTCACAGCCCAACAGCA R: GTGGTACAAGGACGCCATCA | 61 | 162 |

| TNX | Tenascin-X | Ssc.28161 | F: GCTGACAGCGACCGACATAA | 61 | 197 |

| R: CGAGCCCATACAGGACGAAT | |||||

| MYBPH | Myosin binding protein H | Ssc.20879 | F: CGTCAGGTGGGAGAAGCAA R: GAGCGGATGAAGAGGATGG | 61 | 149 |

| TGFB3 | Transforming growth factor, beta 3 | Ssc.27593 | F: TTCCGCTTCAACGTGTCG R: CGCTGCTTGGCTATGTGC | 61 | 158 |

| TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor, beta 1 | Ssc.76 | F: GCTGCTGTGGCTGCTAGTG R: TCGCGGGTACTGTTGTAAAG | 61 | 216 |

| HSP | Heat shock protein 20kDa | Ssc.13823 | F: CTACCGCCCAGGTGCCAA | 61 | 96 |

| R: CGCCAACCACCTTGACGG | |||||

| SLC12A4 | Solute carrier family 12 (potassium/chloride transporters), member 4 | Ssc.4097 | F: CAGCACAAGGTTTGGAGGAA R: CGTAGGTGGTACAGGAAGAT | 61 | 110 |

| GATA-6 | Transcription factor GATA-6 | Ssc.2258 | F: CAGAAACGCCGAGGGTGAA R: GAGGTGGAAGTTGGAGTCAT | 61 | 216 |

| OCA2 | Oculocutaneous albinism 2 | Ssc.15775 | F: CTGCCATCATCGTAGTAGTC R: CTCCAATCAGTGTCCCGTTA | 61 | 192 |

| ART3 | ADP-ribosyltransferase 3 | Ssc.15864 | F: ATGTCTATGGCTTCCAGTTCA R: CTGGCTTATGCTATACACCAC | 61 | 110 |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase | Ssc.4158 | F: GGACTTGAATCATGTTTGTG R: GTTTGGAAACATCTG | 61 | 91 |

| MyHCI | Myosin heavy chain, type I | Ssc.1544 | F: CGACACACCTGTTGAGAAG R: AGATGCGGATGCCCTCCA | 61 | 233 |

| MyHCIIa | Myosin heavy chain, type IIa | Ssc.15909 | F: GGGCTCAAACTGGTGAAGC R: AGATGCGGATGCCCTCCA | 61 | 249 |

| MyHCIIb | Myosin heavy chain, type IIb | Ssc.56948 | F: GTTCTGAAGAGGGTGGTAC R: AGATGCGGATGCCCTCCA | 61 | 234 |

| MyHCIIx | Myosin heavy chain, type IIx | Ssc.56721 | F: CTTCACTGGCGCAGCAGGT R: AGATGCGGATGCCCTCCA | 61 | 257 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Myosin heavy chain expression analysis

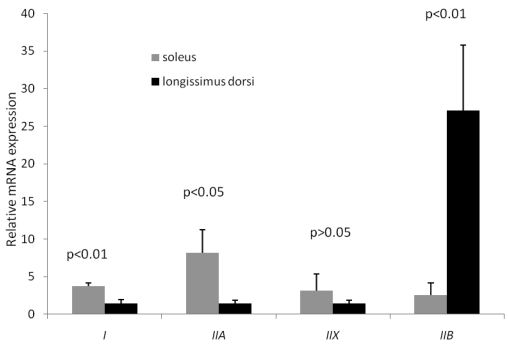

MyHC isoforms are generally considered as the molecular markers of different muscle fiber types. In postnatal growing pigs, type I, IIb, IIa and IIx MyHC are all expressed in skeletal muscle, which are encoded by a distinct gene 16, 17. In this study, MyHCI (oxidative fiber) and MyHCIIa (intermediate fiber) expressions in soleus were significantly higher than their counterparts in longissimus doris, while MyHCIIb (glycolytic fiber) expression in soleus was significantly lower than that in longissimus doris (Figure 1). In particular, the mRNA level of type IIb in longissimus doris was nearly 11 times greater than that in soleus. Therefore, the longissimus doris was composed of more glycolytic type of muscle fibers than fiber composition of soleus. The increasing percentages of type IIb fiber, and decreasing percentages of types I and IIa fibers, are related to increases in drip loss and lightness, which are deteriorative to pork quality 18.

Figure 1.

Expression of four MyHC isoforms in longissimus doris and soleus mRNA by qRT-PCR. The data presented in Y-axis were calculated using the expression values of 2−ΔΔCt of three pigs and expressed as means ± s.d.

3.2 Identification of differentially expressed transcripts between white and red skeletal muscle

The transcriptome analysis indicated that 13241 and 14433 probe sets were expressed in porcine longissimus doris and soleus, respectively. The global expression profile of longissimus doris was compared with that of the soleus group. After quantile normalization and statistical analyses, 550 transcripts with at least 1.5-fold difference were identified at the p < 0.05 significance level (p < 0.05, FC≥1.5). Compared with the expression of transcripts in longissimus doris, a set of 323 transcripts belonged to the up-regulated group, and another set of 227 transcripts belonged to the down-regulated group in soleus. Taking the FC of two or greater as the criteria (p < 0.05, FC≥2), a total of 159 transcripts showed differential expression, of which 107 transcripts were up-regulated and 52 down-regulated in soleus. The differentially expressed transcripts were involved in many functions related to contractile structure and cytoskeleton, extracellular matrix, energy metabolism, stress, transcription regulation and so on (Table 2). The microarray results confirmed several differentially expressed genes between red and white skeletal muscle in the previous studies, such as MyHCIIb, a-actin, HSP20, PGM, fibronectin and muscle LIM protein encoding genes 3, 12, 13. As expected, the expression levels of energy metabolism enzyme genes, cathepsin, collagen protein, oxygenase and slow-type muscle protein encoding genes, were significantly higher in red muscle than in white muscle, which could contribute to the better meat quality of red muscle. In addition, some important transcription factors including GATA-6, TGFB1, TGFB3, MEF2C, EGF and HMOX1 that were not previously known to be expressed in a fiber type manner, were identified as differential expression in microarray analysis. It is interesting as the newly identified factors might be candidates for transcriptional regulation of the specificity of the metabolic and contractile characteristics of different fiber types.

Table 2.

List of some differential expressed genes between red and white muscle of Meishan pigs

| Gene title | Fold change | P value | Structure and function | Unigene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle contraction and cytoskeleton genes | ||||

| myosin heavy chain IIb | -1.51 | 0.023 | striated muscle contraction, actin binding | Ssc.56948 |

| α-actin | 7.52 | 0.007 | striated muscle contraction | Ssc.1901 |

| filamin A, alpha (actin binding protein 280) | 1.83 | 0.009 | striated muscle contraction | Ssc.55452 |

| filamin B, beta (actin binding protein 278) | 1.84 | 0.030 | striated muscle contraction | Ssc.6691 |

| tubulin, beta 2B | 2.50 | 0.004 | microtubule subunit protein, bind to colchicine,vincristine | Ssc.55842 |

| tubulin, beta 6 | 2.02 | 0.046 | microtubule subunit protein, bind to colchicine,vincristine | Ssc.58401 |

| α-actinin | 2.22 | 0.030 | regulate the length of actin | Ssc.5941 |

| integrin, beta 3 | 1.76 | 0.029 | cell adhesion, integrin-mediated signaling pathway, regulation of cell migration | Ssc.44 |

| catenin (cadherin-associated protein), alpha 1 | 1.61 | 0.025 | bind to cadherin | Ssc.58861 |

| myosin binding protein C, slow type isoform 3 | 2.28 | 0.006 | bind to myosin | Ssc.13955 |

| myosin binding protein H | -2.84 | 0.035 | bind to myosin | Ssc.20879 |

| Extracellular matrix genes | ||||

| fibromodulin | 3.12 | 0.013 | protein binding | Ssc.56133 |

| fibronectin | 2.51 | 0.011 | extracellular region | Ssc.16743 |

| tenascin-X | 2.94 | 0.001 | signal transduction | Ssc.28161 |

| tenascin-C | 2.66 | 0.001 | cell adhesion, signal transduction | Ssc.16209 |

| ankyrin 1 isoform 5 | -1.51 | 0.006 | attach to cytoskeleton, membrane-associated protein | Ssc.21745 |

| collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 3.10 | 0.008 | phosphate transport, cell adhesion | Ssc.46811 |

| collagen, type V, alpha 1 | 2.54 | 0.016 | phosphate transport, cell adhesion | Ssc.54853 |

| Metabolic enzyme genes | ||||

| pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 3 | 1.9 | 0.012 | phosphorylate pyruvate dehydrogenase | Ssc.19740 |

| heme oxygenase (decyclizing) 1 | 3.25 | 0.025 | heme oxidation | Ssc.115 |

| phosphoglucomutase | -1.58 | 0.005 | phosphotransferases, carbohydrate metabolic process | Ssc.4307 |

| fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase 2 | 2.12 | 0.022 | carbohydrate metabolic, gluconeogenesis | Ssc.5127 |

| creatine kinase | 1.65 | 0.020 | transferring phosphorus-containing groups | Ssc.9914 |

| phosphofructokinase, platelet, partial | 2.31 | 0.012 | 6-phosphofructokinase activity | Ssc.862 |

| glutathione S-transferase omega | -1.55 | 0.029 | glutathione transferase activity | Ssc.183 |

| ADP-ribosyltransferase 3 | -2.68 | 0.004 | protein amino acid ADP-ribosylation | Ssc.15864 |

| AXL receptor tyrosine kinase | 2.29 | 0.010 | regulates tyrosine phosphorylation in cellular signal transduction | Ssc.6566 |

| protein tyrosine phosphatase 4a2 | -2.01 | 0.014 | dephosphorylation in cellular signal transduction, cell growth control | Ssc.54932 |

| Stress protein genes | ||||

| heat shock protein 2 | 1.91 | 0.005 | response to stress | Ssc.7654 |

| heat shock protein 20kDa | 2.15 | 0.032 | response to stress | Ssc.13823 |

| Transport protein genes | ||||

| solute carrier family 12 (potassium/chloride transporters), member 4 | 2.42 | 0.016 | ion transport | Ssc.4097 |

| aquaporin 3 | -3.66 | 0.026 | water reabsorption | Ssc.3832 |

| oculocutaneous albinism 2 | -12.6 | 0 | citrate transmembrane transport | Ssc.15775 |

| Transcription factor genes | ||||

| transforming growth factor, beta induced | 2.9 | 0.040 | binds to type I, II, IV, VI collagens and fibronectin | Ssc.16671 |

| transforming growth factor, beta 3 | 1.99 | 0.027 | cell differentiation, embryogenesis and development | Ssc.27593 |

| transforming growth factor, beta 1 | 1.85 | 0.003 | immune, regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation | Ssc.76 |

| transcription factor GATA-6 | 2.23 | 0.040 | positive regulation of transcription | Ssc.2258 |

| general transcription factor IIE, polypeptide 2, beta 34kDa | 1.69 | 0.003 | regulation of transcription initiation | Ssc.3369 |

| homeobox protein A10 | 2.27 | 0.001 | regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Ssc.26254 |

| myocyte enhancer factor 2C | 1.58 | 0.011 | regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | Ssc.34788 |

| four and a half LIM domains 1 protein, isoform C | 1.53 | 0.027 | metal ion binding | Ssc.14463 |

| epidermal growth factor | -1.57 | 0.040 | calcium ion binding, integral to membrane | Ssc.87 |

| Hormone genes | ||||

| parathyroid hormone-like hormone | 1.77 | 0.003 | hormone activity | Ssc.9991 |

| Others | ||||

| calponin 1 | 1.67 | 0.015 | actomyosin structure organization and biogenesis, actin and calmodulin binding | Ssc.9013 |

| calcyclin binding protein isoform 1 | -1.76 | 0.012 | ubiquitin-mediated degradation of beta-catenin | Ssc.10299 |

| cathepsin B | 1.59 | 0.045 | proteolysis | Ssc.53773 |

| cathepsin H | 1.83 | 0.018 | proteolysis | Ssc.3593 |

| cathepsin Z | 1.65 | 0.016 | proteolysis | Ssc.16769 |

| mitochondrial ribosomal protein S26 | -2.12 | 0.033 | catalytic function in reconstituting biologically active ribosomal subunits | Ssc.12554 |

| p53 protein | 1.64 | 0.028 | control of cell proliferation | Ssc.16010 |

| p55 TNF receptor superfamily, member 1A | 1.51 | 0.008 | cell surface receptor linked signal transduction | Ssc.4674 |

| interleukin 15 | -1.59 | 0.031 | stimulating the proliferation of T-lymphocytes | Ssc.8833 |

| cytochrome P450, family 27, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 1.73 | 0.012 | biosynthesis of steroids, fatty acids and bile acids | Ssc.3804 |

“+” and “-” indicated the up- and down- regulated expression in soleus group, respectively.

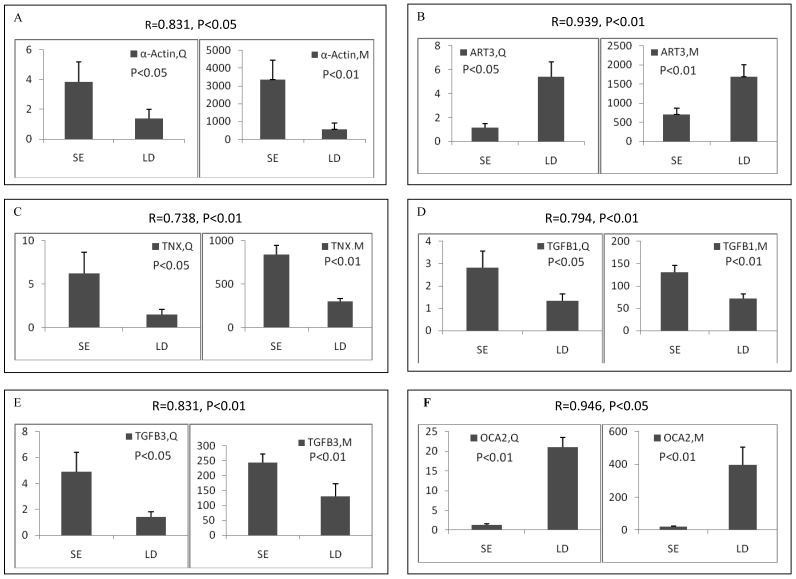

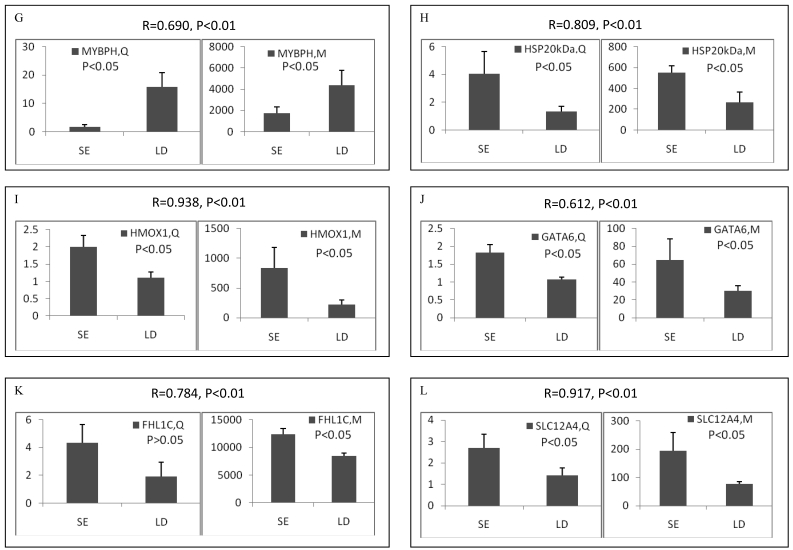

3.3 Validation of microarray data by qRT-PCR

Among the differentially expressed transcripts identified by microarray, twelve known genes were selected for validation by qRT-PCR. These genes included three down-regulated genes (ART3, MYBPH and OCA2) and nine up-regulated genes (α-actin, FHL1C, GATA-6, HMOX1, HSP, SLC12A4, TGFB1, TGFB3 and TNX) in soleus. Except for FHL1C, all the other selected genes showed significant (p < 0.05 or 0.01) differential expression between two muscles in the qRT-PCR results. Remarkably, qRT-PCR showed significant correlation with microarray analysis, with all the genes being the similar expression patterns in both methods (Pearson correlation coefficient ranged from 0.612 to 0.946) (Figure 2). The fold changes obtained by qRT-PCR were much more or less than those obtained in the microarray. This may be due to the greater accuracy of quantitation provided by qRT-PCR in comparison to microarrays, the differences in the dynamic range of the two techniques, and the lack of specificity in the primers designed to discriminate gene family members at the level of primary screening by DNA arrays 19. However, the trends were same between the results of two methods, showing the reliability of the microarray analysis.

Figure 2.

Validation of differentially expressed genes between longissimus doris (LD) and soleus (SE) by qRT-PCR. The data presented in Y-axis indicated the relative mRNA expression of both microarray (M) and qRT-PCR (Q) and expressed as means of three pigs ± s.d. The correlation coefficient (R) and the corresponding significance value (P) were shown above their respective columns.

3.4 Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

To elucidate the relationship between gene differential expression pattern and phenotypic difference of red and white muscle, we examined the functional bias of 550 differentially expressed transcripts according to Gene Ontology classifications. These differentially expressed transcripts were grouped into 404 GO terms based on biological process GO terms. The most enriched GO terms included cellular biopolymer metabolic process, protein metabolism and cellular protein metabolism (Table 3). Analyses of GO also indicated that there were 108 GO terms identified by cellular component classification, and 64 GO terms identified by molecular function classification.

Table 3.

List of the top 20 enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms based on GO classifications

| Biological process | Count | Percent | Molecular function | Count | Percent | Cellular component | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cellular biopolymer metabolic process | 41 | 3% | pyrophosphatase activity | 6 | 6% | intracellular organelle | 53 | 10% |

| protein metabolism | 23 | 2% | G-protein coupled receptor activity | 5 | 5% | intracellular organelle part | 38 | 7% |

| cellular protein metabolism | 19 | 2% | cation transporter activity | 4 | 4% | cytoplasm | 33 | 6% |

| biopolymer biosynthesis | 14 | 1% | transcription coactivator activity | 3 | 3% | cytoplasmic part | 32 | 6% |

| cellular macromolecule biosynthetic process | 14 | 1% | symporter activity | 3 | 3% | intracellular membrane-bound organelle | 31 | 6% |

| cellular biopolymer biosynthetic process | 14 | 1% | phosphoric monoester hydrolase activity | 3 | 3% | intracellular non-membrane-bound organelle | 27 | 5% |

| DNA metabolism | 13 | 1% | iron ion binding | 2 | 2% | cytoskeleton | 14 | 3% |

| regulation of cellular metabolism | 13 | 1% | carbohydrate kinase activity | 2 | 2% | nucleus | 13 | 2% |

| organ morphogenesis | 13 | 1% | protein kinase activity | 2 | 2% | nuclear part | 12 | 2% |

| regulation of macromolecule metabolic process | 13 | 1% | cysteine-type peptidase activity | 2 | 2% | cytoskeletal part | 11 | 2% |

| biopolymer modification | 12 | 1% | exopeptidase activity | 2 | 2% | chromosome | 11 | 2% |

| negative regulation of cellular physiological process | 12 | 1% | phosphofructokinase activity | 2 | 2% | chromosomal part | 9 | 2% |

| cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 12 | 1% | anion transporter activity | 2 | 2% | actin cytoskeleton | 8 | 1% |

| RNA metabolism | 11 | 1% | protein methyltransferase activity | 2 | 2% | intracellular organelle lumen | 7 | 1% |

| transcription | 11 | 1% | S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase activity | 2 | 2% | chromatin | 7 | 1% |

| regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism | 11 | 1% | peptide receptor activity, G-protein coupled | 2 | 2% | organelle envelope | 6 | 1% |

| intracellular signaling cascade | 11 | 1% | double-stranded DNA binding | 2 | 2% | contractile fiber | 6 | 1% |

| protein modification | 11 | 1% | P-P-bond-hydrolysis-driven transporter activity | 2 | 2% | endoplasmic reticulum | 5 | 1% |

| cell morphogenesis | 11 | 1% | phosphorylase activity | 2 | 2% | contractile fiber part | 5 | 1% |

| intracellular transport | 10 | 1% | copper ion binding | 1 | 1% | intrinsic to membrane | 5 | 1% |

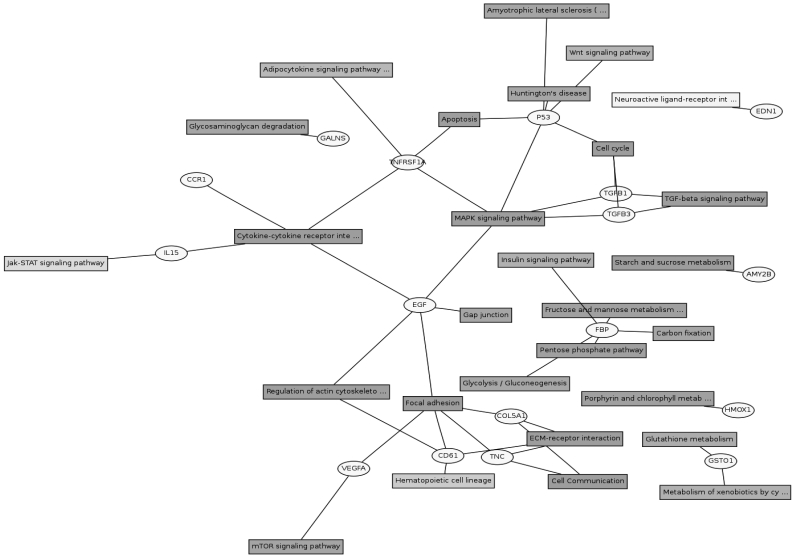

3.5 Pathway analysis

Twenty eight signaling pathways were identified using KEGG pathway database (Figure 3). The genes could be assigned into numerous subcategories including the extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction (COL5A1, COL1A2, TNC, COL1A1 and FN1), focal adhesion (COL5A1, COL1A2, TNC, FLNB, FLNA, COL1A1 and FN1), TGF-beta signaling pathway (TGFB1 and TGFB3), MAPK signaling pathway (p53, EGF, TNFRSF1A, TGFB1 and TGFB3) , cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (CCR1, IL15, EGF and TNFRSF1A), regulation of actin cytoskeleton (ITGB3 and EGF), mTOR signaling pathway (VEGFA), JAK-STAT signaling pathway (IL15), cell cycle (p53) and so on. There were cross-talks among these pathways, as one gene might participate in several signaling pathways.

Figure 3.

Gene pathway network about the differential expressed genes. The differential expressed genes and the corresponding pathways were shown in the circles and boxes, respectively.

The ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion and cell communication pathways accounted for a large part of the involved differentially expressed genes. The major constituents of the ECM are collagens, proteoglycans, and adhesive glycoproteins. In addition to being responsible for the strength and form of tissues, each collagen type has specific sequences providing them with special features such as flexibility and the ability to interact with other matrix molecules and cells 20. Specific interactions between cells and ECM mediated by transmembrane molecules or other cell-surface-associated components, lead to a direct or indirect control of cellular activities such as adhesion and migration. Focal adhesions are large, dynamic protein complexes through which the cytoskeleton of a cell connects to the ECM. They actually serve for not only the anchorage of the cell, but can function beyond that as signal carriers (sensors), which inform the cell about the condition of the ECM and thus affect their behavior 21. Collagen is an abundant connective tissue protein and is a contributing factor to variation in meat tenderness and texture. Although collagen constitutes <2% of most skeletal muscles, it is associated with background toughness and can be quite resistant to physical breakdown during cooking 22. No significant difference in total amount of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) was found, but a significant difference in the ratio of GAG/collagen was found between the tough (m. semitendinosus) and tender (m. psoas major) muscles 23. The higher expressions of some collagen encoding genes were detected in red muscle than in white muscle in this study, reflecting the composition difference of collagens in two types of muscles.

Other significant signaling pathways contained TGF-beta signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, MAPK signaling pathway, mTOR Signaling pathway and JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Two genes of the TGFB signaling pathway (TGFB1 and TGFB3) which also participated in the MAPK signaling pathway, were up-regulated in soleus. TGFB1 plays an important role in controlling the immune system, and shows different activities on different types of cell, or cells at different developmental stages. Most immune cells (or leukocytes) secrete TGFB1 24. TGFB3 is a type of protein, known as a cytokine, which is involved in cell differentiation, embryogenesis and development 25. During skeletal muscle development, TGFB1 is a potent inhibitor of muscle cell proliferation and differentiation, as well as a regulator of extracellular matrix (ECM) production 26. TGFB1 induces an incomplete shift from a slow to a fast phenotype in regenerating slow muscles and that conversely, neutralization of TGFB1 in regenerating fast muscle leads to a transition towards a less fast phenotype 27. TGFB1 is also able to induce synthesis of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in myoblasts and myotubes. CTGF induced several ECM constituents such as fibronectin, collagen type I and α 4, 5, 6, and β1 integrin subunits in myoblasts and myotubes 28. Stimulation with TGFB1 caused a 14.8-fold increase in collagen I, alpha 1 mRNA and a fourfold increase in fibronectin mRNA abundance in Human Tenon Fibroblasts 29. In this study, the expression levels of collagen I, alpha 1 and fibronectin were more 3.1- and 2.51-fold in soleus than in longissimus doris, while the expression levels of TGFB1 and TGFB3 were more 1.85- and 1.99-fold in soleus than in longissimus doris. Thus, the correlation between their expression trends was positive, which was consistent with their roles in regulating ECM production. Moreover, since TGFB1 influences some aspects of fast muscle-type patterning during skeletal muscle regeneration 27, it will be worthwhile in further investigation to determine at the cellular level how TGFB1 influences fibre type formation and characteristics.

Besides the above identified pathways, GATA-6 is another important differentially expressed transcription factor that might affect the expression of specific fiber types. GATA proteins are a family of transcription factors with two zinc fingers that directly bind DNA regulatory elements containing a consensus (A/T)GATA(A/G) motif. To date, six mammalian members of the GATA family have been identified that can be divided, on the basis of sequence and expression similarities, into two subgroups 30. The GATA-4/5/6 subfamily is expressed within various mesoderm- and endoderm-derived tissues including the heart, liver, lung, gonads, and small intestine 31. During development GATA-6 becomes the only member of the family expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and has been linked to the differentiated phenotype of these cells 32. Overexpression of GATA-6 significantly decreased endogenous telokin and 130-kDa MLCK expression in A10 vascular smooth muscle cells. In contrast, expression of the 220-kDa MLCK and calponin were markedly increased. GATA-6 has been shown to bind directly to the telokin and 130-kDa MLCK promoters at consensus binding sites 33, 34. Knockdown of endogenous GATA-6 in primary human bladder smooth muscle cells led to decreased mRNA levels of the differentiation markers: α-smooth muscle actin, calponin, and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 35. In the present study, compared with these in white muscle, the expressions of GATA-6, calponin and α-actin were all up-regulated in red muscle. Therefore, it can be inferred that GATA-6 also possibly regulates the expression of myosin light chain kinase, calponin and actin in skeletal muscle cells.

In summary, we have identified the global changes of gene expression in porcine red and white muscle. The results indicated distinguishable trends in ECM structure, contractile structure and cytoskeleton, collagen, focal adhesion, immune response and energy metabolism between two muscles. Some potential cascades identified in the study merit further investigation at the cellular level in the function of controlling the fibre type formation and characteristics. Although the work was limited to three animals in each group and to a single time point, the present microarray analysis provided new information that increased our understanding of governing the expression of specific fiber types.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported financially by National Natural Science Foundation of P. R. China (30500358), the Agricultural Innovation Fund of Hubei Province, the National High Technology Development Project (“863” project), the Creative Team Project of Education Ministry of China (IRT0831) and the National “973” Program of P. R. China (2006CB102102).

References

- 1.Matsakas A, Patel K. Skeletal muscle fibre plasticity in response to selected environmental and physiological stimuli. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:611–629. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi YM, Kim BC. Muscle fiber characteristics, myofibrillar protein isoforms, and meat quality. Livest Sci. 2009;122:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim NK, Joh JH, Park HR. et al. Differential expression profiling of the proteomes and their mRNAs in porcine white and red skeletal muscles. Proteomics. 2004;4:3422–3428. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maltin C, Balcerzak D, Tilley R. et al. Determinants of meat quality: tenderness. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:337–347. doi: 10.1079/pns2003248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang KC, da Costa N, Blackley R. et al. Relationships of myosin heavy chain fibre types to meat quality traits in traditional and modern pigs. Meat Sci. 2003;64:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(02)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang KC. Key signalling factors and pathways in the molecular determination of skeletal muscle phenotype. Animal. 2007;1:681–698. doi: 10.1017/S1751731107702070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlsson AH, Klont RE, Fernandez X. Skeletal muscle fibres as factors for pork quality. Livest Prod Sci. 1999;60:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klont RE, Brocks L, Eikelenboom G. Muscle fibre type and meat quality. Meat Sci. 1998;49:219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood JD, Nute GR, Richardson RI. et al. Effects of breed, diet and muscle on fat deposition and eating quality in pigs. Meat Sci. 2004;67:651–667. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallinson J, Meissner J, Chang KC. Calcineurin signaling and the slow oxidative skeletal muscle fiber type. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;277:67–101. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)77002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duggan DJ, Bittner M, Chen Y. et al. Expression profiling using cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 1999;21(Suppl):S10–S14. doi: 10.1038/4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell WG, Gordon SE, Carlson CJ. et al. Differential global gene expression in red and white skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:763–768. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai Q, McGillivray C, da Costa N. et al. Development of a porcine skeletal muscle cDNA microarray: Analysis of differential transcript expression in phenotypically distinct muscles. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai S, Cassady JP, Freking BA. et al. Annotation of the Affymetrix porcine genome microarray. Anim Genet. 2006;37:423–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Myosin isoforms in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:493–501. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefaucheur L, Ecolan P, Plantard L, Gueguen N. New insights into muscle fiber types in the pig. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:719–730. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu YC, Kim BC. The relationship between muscle fiber characteristics, postmortem metabolic rate, and meat quality of pig longissimus dorsi muscle. Meat Sci. 2005;71:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen HB, Li CC, Fang MD. et al. Understanding Haemophilus parasuis infection in porcine spleen through a transcriptomics approach. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uitto VJ. Extracellular matrix molecules and their receptors: an overview with special emphasis on periodontal tissues. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:323–354. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ. et al. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weston AR, Rogers RW, Althen TG. The role of collagen in meat tenderness. Professional Animal Scientist. 2002;18:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen ME, Kolset SO, Sørensen T, Eggen KH. Sulfated glycosaminoglycans and collagen in two bovine muscles (M. Semitendinosus and M. Psoas major) differing in texture. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:1445–1452. doi: 10.1021/jf980601y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letterio J, Roberts A. Regulation of immune responses by TGF-beta. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herpin A, Lelong C, Favrel P. Transforming growth factor-beta-related proteins: an ancestral and widespread superfamily of cytokines in metazoans. Dev Comp Immunol. 2004;28:461–485. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Velleman SG. Effect of transforming growth factor-beta1 on decorin expression and muscle morphology during chicken embryonic and posthatch growth and development. Poult Sci. 2009;88:387–397. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noirez P, Torres S, Cebrian J. et al. TGF-beta1 favors the development of fast type identity during soleus muscle regeneration. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2006;27:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vial C, Zúñiga LM, Cabello-Verrugio C. et al. Skeletal muscle cells express the profibrotic cytokine connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2), which induces their dedifferentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:410–421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer-Ter-Vehn T, Gebhardt S, Sebald W. et al. p38 inhibitors prevent TGF-beta-induced myofibroblast transdifferentiation in human tenon fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1500–1509. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patient RK, McGhee JD. The GATA family (vertebrates and invertebrates) Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:416–422. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molkentin JD. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38949–38952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrisey EE, Ip HS, Lu MM, Parmacek MS. GATA-6: a zinc finger transcription factor that is expressed in multiple cell lineages derived from lateral mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;177:309–322. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin F, Herring BP. GATA-6 can act as a positive or negative regulator of smooth muscle-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4745–4752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin F, Hoggatt AM, Zhou J, Herring BP. 130-kDa smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase is transcribed from a CArG-dependent, internal promoter within the mouse mylk gene. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1599–C1609. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00289.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanematsu A, Ramachandran A, Adam RM. GATA-6 mediates human bladder smooth muscle differentiation: involvement of a novel enhancer element in regulating α-smooth muscle actin gene expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1093–C1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00225.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]