Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate sensitivity and specificity of self-administrated tests aimed at pain provocation of posterior and/or anterior pelvis pain and to investigate pain intensity during and after palpation of the symphysis. A total of 175 women participated in the study, 100 pregnant women with and 25 pregnant women without lumbopelvic back pain and 50 non-pregnant women. Standard pain provocation tests were compared with self assessed tests. All women were asked to estimate pain during and after palpation of the symphysis. For posterior pelvic pain, the self-test of P4 and Bridging test had the highest sensitivity of 0.90 versus 0.97 and specificity of 0.92 and 0.87. Highest sensitivity for self-test for anterior pelvic pain was pulling a mat 0.85. Palpation of symphysis was painful and persistency of pain was the longest among women who fulfilled the criteria for symphyseal pain. There were overall significant differences between the groups concerning intensity and persistency of pain (P < 0.001). Our results indicate that pregnant women can perform a screening by provocation of posterior pelvic pain by self-tests with the new P4 self-test and the Bridging test. Palpation of the symphysis is painful and should only be used as a complement to history taking, pain drawing and pulling a MAT-test.

Keywords: Low back pain, Pregnancy, Provocation tests, Pelvic girdle pain, Screening

Introduction

Every second woman has some type of lumbopelvic pain in pregnancy and in 75–83% of the cases, the pain is related to the pelvic girdle with or without pain in the lumbar spine region [6, 17]. The pelvic girdle includes muscles and ligaments in the pelvis as well as the posterior sacroiliac joints and the symphysis. Specific symphyseal pain affects 9.9% [3] of pregnant women, which in Sweden amounts to about 10,000 out of the 100,000 women who give birth a year.

Women with pelvic girdle pain (PGP) describe stabbing, aching pain between the posterior iliac crests and the gluteal folds, with or without radiation down the leg [13, 25]. The classification of PGP can be made only after exclusion of lumbar causes [25]. Pain in the pubic bone, sometimes reported as an unpleasant sensation of movement, may radiate to the pelvic floor and down the thigh. Pain from the symphysis, as well as from other parts of the pelvic girdle typically increases in intensity from weight-bearing activities, such as standing, rising and walking [9, 13].

The aetiology of PGP is unknown, but hormonal and biomechanical causes are discussed [11, 13, 16]. During pregnancy, there is a hormonal induced relaxation of the pelvic joints to prepare for delivery. The increased mobility may lead to higher demands on stabilizing ligaments and muscles. When the demand is not met, pain may follow.

Most women recover from pregnancy-related PGP; however, 8.6% had severe persistent pain 2 years after pregnancy [2]. Women with persistent pain report high disability and difficulties in returning to work [8]. In a 12-year follow-up study of women with some type of lumbopelvic pain severe enough to require sick leave while pregnant, 92% reported pain during a subsequent pregnancy and 86% had recurrent pain while not pregnant [4]. Pregnancy is thereby a risk factor for persistent lumbopelvic pain requiring long-term sick leave.

To study the relatively small group with risk of persisting pain, screening needs to be performed using large surveys. When evaluating PGP postpartum, many studies use questionnaires [4, 21, 24], some including a pain drawing [14, 15, 17, 23]. However, clinical experience shows that some women have difficulties in anatomically locating the pain on a pain drawing. To date, questionnaires have not included pain provocation tests, which make the identification of PGP less reliable in a large survey. In the guidelines for PGP, recommended tests for classification are: the posterior pelvic pain provocation test, Patrick’s Faber test, palpation of long dorsal sacroiliac ligament and Gaenslen’s test [25]. These tests, with exception of the Patrick’s Faber test, require that the women visit an examiner. If these tests could be modified so that the women were able to perform them as a self-test, this would help obtain information that complements surveys and longitudinal studies including questionnaires. Thus there is a need for development of self-administered tests and a need to evaluate them before they may be used as a screening tool to better understand the course of PGP.

To evaluate pain from the symphysis, the recommended tests are the modified Trendelenburg test and palpation of the joint [1]. Palpation of the symphysis was defined by Albert et al. as pain >5 s after palpation.

Our clinical experience has shown that palpation of symphysis is very painful not only for women with PGP, but also for pregnant women without symphyseal pain symptoms. There is a lack of knowledge about the pain during the palpation and persisting pain after. There is also a need for additional/modified tests for women with pain from the symphysis to determine that tests could be performed independently by the patient as a screening tool in studies.

The aim of this study was therefore twofold: (1) to investigate sensitivity and specificity of self-administrated tests aimed at pain provocation of posterior pelvis and/or anterior pelvis pain in pregnant women with or without low back pain and in non-pregnant women without low back pain. (2) To investigate the pain intensity during and persistency of pain after palpation of the symphysis in pregnant women with and without lowback pain and in non-pregnant women.

Methods

A total of 175 women participated in the study. The women included consisted of a consecutive series of 100 pregnant women with lumbopelvic pain referred to a specialist clinic and 25 pregnant women with no lumbopelvic pain recruited from prenatal healthcare clinics in the Gothenburg region. Additionally, a group of 50 non-pregnant fertile women denying lumbopelvic pain during the last 12 months were included. They were recruited among friends and staff at the hospital or students at the university. Demographic data such as age, parity and gestational weeks of all the participants are presented in Table 1. The group of pregnant women with lumbopelvic pain was well distributed concerning educational level and sedentary versus active lifestyle.

Table 1.

Age, parity and gestational weeks in the women who were tested in the study

| Pregnant women with lumbopelvic pain n = 100 |

Pregnant women without lumbopelvic pain n = 25 | Non-pregnant women n = 50 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years Mean (±SD) |

30.5 (4.8) | 30.0 (3.2) | 28.2 (8.4)* |

|

Parity Median (min–max) |

2 (1–6) | 1 (1–3)* | 0 (0–4)** |

| Gestational week Mean (±SD) (range) |

24.6 (4.1) (14–31) |

24.0 (7.5) (7–38) |

– |

* Significant difference to pregnant women with pelvic pain (P < 0.01)

** Significant difference to pregnant women with pelvic pain and without pelvic pain (P < 0.001)

The women gave their consent to participate in the study after receiving verbal and written information. To exclude women with exclusive pain from the lumbar spine, active end range movements were performed in flexion, extension, rotation and lateral flexion. If the women could perform the movements to end range without pain provocation in the lumbar spine, lumbar pain was excluded as the cause of pain. The hip was excluded as the cause of pain with end range tests of the hip joints in abduction, flexion, internal and external rotation. The women also underwent a straight leg raising test to exclude nerve-root pain. To verify the pain/absence of pain, the women were interviewed about their daily symptoms from their pelvic girdle and lower back, pain in general and specifically pain when turning in bed as this activity often provokes lumbopelvic pain. For pain location, the women also made markings on a pain drawing [20].

Subsequently, the women performed pain provocation tests of sacroiliac and symphyseal joints in a standardized order. The test protocol was assessed in seven pregnant women with low back pain before the start of the main study. Some minor adjustments were made about the order of the tests and the instructions given. The test protocol consisted of the following tests performed by the examiner and the presence/absence of pain was noted:

| The posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4 test) [18] | Lying in the supine position with 90° flexion at the hip, the examiner presses on the flexed knee, along the longitudinal axis of the femur. Positive test = reproducing the pain in the SI area |

| Patrick Faber test [1] | Lying in the supine position with one hip flexed, abducted and rotated so that the heel rests on the opposite kneecap. Positive test = reproducing the pain in the SI area |

| The modified Trendelenburg test [1] | Standing on one leg, flexing the other with the hip and knee at 90°. Positive test = reproducing the pain in the SI area |

The following self-administered tests were performed by the women and the absence or presence of familiar pain was noted:

| The self-assessed P4 | Lying in the supine position with 90° flexion at the hip the patient presses on the flexed knee, along the longitudinal axis of the femur. Positive test = reproducing the pain in the SI area |

| Four-point kneeling with extension of one leg |

In four-point kneeling, the patient extended one leg at a time Positive test = pain in the symphysis or SI area |

| Bridging with extension of one leg |

The patient lifted the buttock and extended one leg Positive test = reproducing the pain in the SI area |

| Pulling a mat (MAT-test) |

The patient performed a movement of hip abduction and adduction simulating the movement to pull a mat Positive test = pain in the symphysis |

All tests were performed once on each leg (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 1.

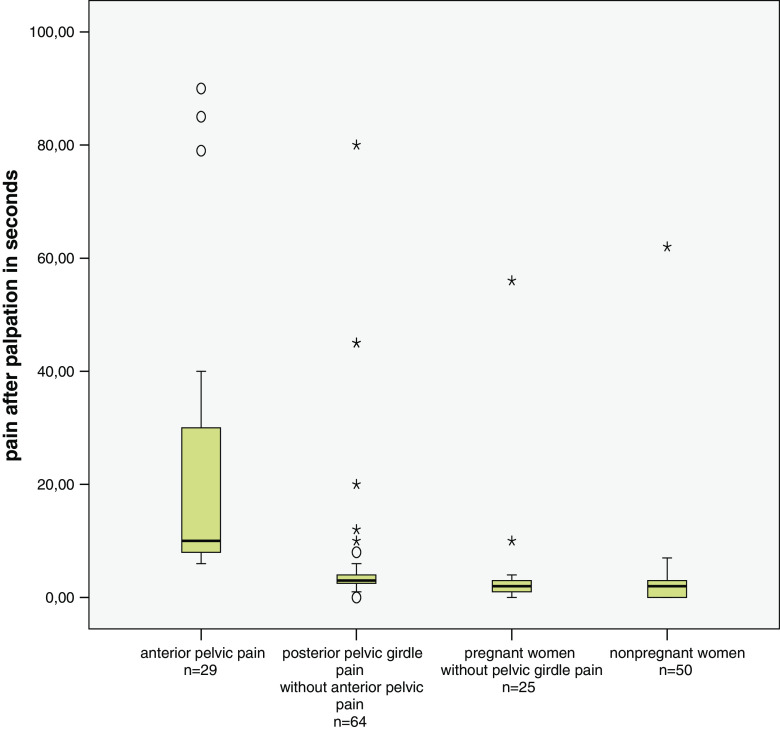

Pain after palpation of symphysis

Fig. 2.

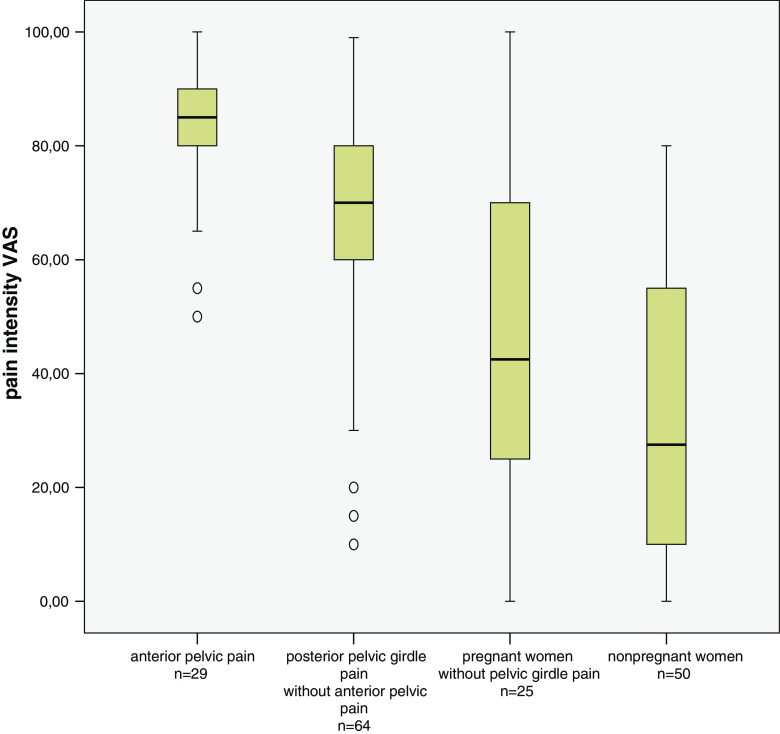

Pain intensity VAS. Asterisks and circles indicate extreme values

Fig. 3.

The self-assessed P4

Fig. 4.

Four-point kneeling with extension of one leg

The women were also asked to estimate pain intensity during the palpation of the symphysis [1] on a visual analogue scale (VAS), consisting of a 100-mm horizontal line, ranging from no pain to worst possible pain [10]. A pressure of 15 kg was applied during 5 s and persisting pain after 5 s was described as a positive test [1]. In addition to this, the time of pain persistence after palpation was documented.

To standardize the performances of the tests, examiners trained together before starting the inclusion.

As a reference standard for posterior PGP, the following definitions according to Östgaard [19] were used (All criteria had to be fulfilled):

A history of time and weight-bearing related pain in the posterior pelvis, deep in the gluteal area

A pain drawing with well-defined markings of pain in the buttocks distal and lateral to the L5-S1 area, with or without radiation to the posterior thigh or knee, but not into the foot

A positive posterior pelvic pain provocation test

Free movements in the hips and spine and no nerve-root syndrome

Pain when turning in bed.

As a reference standard for anterior pelvic pain the following definitions were used (All criteria had to be fulfilled):

A history of symphyseal pain

Pain in the pubic region during palpation of the symphysis.

For identification of posterior pelvic pain according to reference standard, the following four self-administered tests were performed: self-assessed P4, four-point kneeling with extension of one leg, bridging with extension of one leg and modified Trendelenburg test.

For identification of anterior pelvic pain according to reference standards, the following two self-administered tests were performed: pulling-a-mat test and modified Trendelenburg test.

Statistical methods

SPSS version 15.0 was used for the statistical analyses. Comparisons among the groups at baseline were performed with an ANOVA for the normally distributed continuous variables and with a Kruskal–Wallis analysis for the variables on the ordinal level.

Pain intensity between the groups after palpation of the symphysis and the duration of pain in seconds after palpation were analysed with Kruskal–Wallis test. Comparisons between two groups were performed with the Mann–Whitney U test. For multiple comparisons, Bonferroni corrections were made. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Sensitivity and specificity were analysed for PGP and anterior pelvic girdle pain with the reference standard according to the definitions described above.

The ethic research committee approved the study and all participating women gave their informed consent before entering the study.

Results

Results of the tests for all three groups are presented in Table 2. For the women who fulfilled the criteria stated as the reference standard for PGP used in this study, the sensitivity of the self-administered tests is described in Table 3. The self-test of P4 and the bridging test had the highest sensitivity. The calculation of the specificity was based on those who did not fulfil the reference standard for PGP. The specificity was high for the different tests, with scores ranging from 0.87 to 0.97 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results of the test in the three groups of women

| Test | Pregnant women with lumbopelvic pain n = 100 |

Pregnant women without lumbopelvic pain n = 25 | Non-pregnant women n = 50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior pain | |||

| History of posterior pain (n) | 96 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive pain drawing (n) | 94 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive P4 (n) | 97 | 1 | 1 |

| Positive Patrick’s Faber test (n) | 53 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive, modified Trendelenburgs test (n) | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| ASLR, 0–10 | 3 (0–9) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–3) |

| Pain while turning in bed, n | 91 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive self-assessed P4 (n) | 84 | 0 | 0 |

| Four-point kneeling with leg extension | 50 | 1 | 0 |

| Positive Bridging test (n) | 69/74a | 1 | 0 |

| Fulfilling defined criteria for posterior pain | 89 | 0 | 0 |

| Anterior pain | |||

| History of symphyseal pain (n) | 38 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive pain drawing (n) | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive palpation of the symphysis (n) | 37 | 1 | 2 |

| Positive modified Trendelenburgs test (n) | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive four-point kneeling test (n) | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive functional test ‘pulling a mat’ (n) | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Fulfilling defined criteria for anterior pain | 27 | 0 | 0 |

a n = 74

Table 3.

The sensitivity is based on the 89 women who fulfilled reference standard of PGP

| PGP including P4 test according to definition in this study | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity n = 89 |

Specificity n = 36 |

|

| Self-test P4 | 0.90 | 0.92 |

| Bridging test | 0.97a | 0.87 |

| Four-point kneeling | 0.46 | 0.88 |

| Mod Trendelenburg test | 0.6 | 0.97 |

The specificity is based on 36 women who did not fulfil the reference standard. 11 pregnant women with low back pain and 25 pregnant women with no low back pain

a69 of the 89 women performed the Bridging test in one group and 31 of 36 women in the other group

The sensitivity and specificity of the self-administered tests (and Patrick’s test performed by an examiner), using a positive P4 test as reference standard, are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

The sensitivity is based on the 98 women who had a positive P4 test performed by an examiner

| Posterior pelvic pain provocation test (4-p) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity n = 98 |

Specificity n = 27 |

|

| Self-test P4 | 0.84 | 1.0 |

| Patrick’s test | 0.55 | 0.96 |

| Bridging test | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| Four-point kneeling | 0.51 | 0.96 |

| Mod Trendelenburg test | 0.37 | 1.0 |

The specificity is based on 27 women with negative P4 test performed by an examiner. 24 pregnant women with no low back pain and 3 pregnant women with low back pain

The self-test of P4 had a sensitivity of 0.84. Notable is that Patrick’s test, performed by an examiner, had a sensitivity of 0.55.

Of the women who fulfilled the criteria of anterior pelvic pain according to the reference standard, the sensitivity for the functional test used was high for a positive pain drawing (0.96) and for the MAT-test (0.85) (Table 5). The definition used for a positive pain drawing was when the women had marked pain over the symphyseal area. The specificity based on the women who did not fulfil the reference standard was also high for the MAT-test and positive pain drawing.

Table 5.

The sensitivity is based on the 27 women who fulfilled the reference standard for anterior pelvic pain used in this study

| Anterior pelvic pain according to definition in this study | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity n = 27 |

Specificity n = 98 |

|

| Positive pain drawing | 0.96 | 0.85 |

| Pulling a mat | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| Mod Trendelenburg test | 0.48 | 0.90 |

The specificity is based on 98 women who did not meet the reference standard used in this study. 73 pregnant women with low back pain and 25 pregnant women with no low back pain

The specificity for all tests included in this study was also calculated with 50 non-pregnant women without low back pain. The results indicate high specificity for all the tests (Table 6).

Table 6.

The specificity for the functional self-tests for posterior pelvic pain and for self-tests for anterior pelvic pain including pain drawing is based on the 50 non-pregnant woman with no low back pain

| Test for posterior pelvic pain | Specificity n = 50 |

Test for anterior pelvic pain n = 50 |

Specificity n = 50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-test P4 | 1.0 | Positive pain drawing | 1.0 |

| Bridging test | 1.0 | Pulling a mat | 1.0 |

| Four-point kneeling | 1.0 | Mod Trendelenburg test | 1.0 |

| Mod Trendelenburg test | 1.0 |

Pain intensity and pain duration from the palpation are presented in Figs. 5 and 6. The test was painful in the majority of the women and the overall differences between groups were significant (P < 0.001). When performing additional multiple two-group comparisons (with Bonferroni correction), the comparisons were significant (P < 0.01) except for the difference between the pregnant women without low back pain and the non-pregnant women. The duration of pain was longest among women who fulfilled the criteria for symphyseal pain and the over-all difference between groups was significant (P < 0.001). As in the analysis for pain intensity, the additional two-group analyses were significant (P < 0.01) except for the difference between the pregnant women without low back pain and the non-pregnant women.

Fig. 5.

Bridging with extension of one leg

Fig. 6.

Pulling a mat (MAT-test)

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that women can perform the screening test for PGP at home and that the painful palpation of the symphysis may be replaced by a functional test and a pain drawing. However, due to the fact that most pregnant women were recruited from a special clinic and that most of the non-pregnant women were health care providers, future trials are needed before generalisation to other populations can be made.

Posterior pelvic pain provocation tests

The results of this study indicate that the P4 self-test and the Bridging test are accurate as an initial screening tool to classify posterior PGP. The P4 self-test and the Bridging test have high sensitivity when compared with that of the P4 test, which implies that the test identifies posterior PGP when it is present. The two new self-administered tests have high specificity when compared with that of the P4 test in all tested groups of women, with that of which implies that the tests correctly reject the classification of PGP.

In a previous trial, it was shown that the P4 test had a higher sensitivity for unilateral posterior PGP than Patrick’s test (0.84 and 0.42 respectively) [1]. The P4 self-test and the Bridging test are in accordance with the P4 test regarding sensitivity and specificity, indicating that these tests are good in spite of the moderate specificity when compared with that of the Patrick’s test. As the four-point kneeling test did not show as high sensitivity in comparison with the two recommended pain provocation tests, or in comparison with the P4 self-test and the Bridging test, the test cannot be recommended.

The aetiology of PGP is unknown and the origin of the pain is not identified. Therefore, the provoked structure of the test cannot be defined [18]. Until the aetiology is better understood, the goal of the provocation test is identification of a familiar pain. The tests still have a value in a clinical reasoning as good effect of treatment for identified PGP syndrome has been reported [25]. Additionally, if women can do the first screening at home, larger samples may be studied which is needed in future epidemiological studies.

Although the provoked structures by the P4 test are unknown, we can speculate that the test produces a ventral separation and a dorsal compression of the posterior sacroiliac joints. The same mechanism may occur during the modified pain provocation tests (the P4 self-test and the Bridging). On the contrary, during the modified four-point kneeling test, the biomechanical hypothesis of the test is that a ventral compression and dorsal separation occur in the posterior sacroiliac joints. This ought to happen due to the gravity man muscle action on the pelvis. If this theory is correct, it may explain why the sensitivity is higher for the P4 self-test and the Bridging test when compared with the four-point kneeling test.

The biomechanical hypothesis behind the Patrick’s test may be a ventral separation and a dorsal compression in the posterior sacroiliac joints. A reflection though is that a great deal of the movement occurs in the hip joint and that the load on the pelvic structures is relatively low. This may be one reason why the Patrick’s test does not have as high sensitivity as the P4 test or the P4 self-test and the Bridging test.

Anterior pelvic pain provocation tests

Palpation of the symphysis pubis is painful for most pregnant women, irrespective of the presence or absence of symphyseal pain. In addition, 35% of the non-pregnant women reported VAS ≥50 mm. A prerequisite for a positive palpation test is pain duration of more than 5 s [1]. The results of this study indicate that for most women pain persisted longer than 5 s and it persisted for the longest in the group of pregnant women with symphyseal pain. Interestingly, the palpation of the symphysis was negative in 26% of the women with symphyseal pain according to the pain history.

The high sensitivity and specificity identified for symphysis palpation indicate that it is an accurate test. A lower sensitivity (0.60 vs. 0.74) and a higher specificity (0.99 vs. 0.89–0.96), as compared to the result of this study, have been reported by Albert et al. [1]. The higher specificity in the study by Albert et al. may be explained by their larger sample size. In a recent smaller study, lower sensitivity (0.59) as well as lower specificity (0.50) was reported for the symphysis palpation [5].

The pain drawing showed the highest sensitivity, whereas the modified Trendelenburg test and four-point kneeling test had the lowest sensitivity. In a woman with a history of symphyseal pain, combining the pain drawing and pulling a MAT-test shows the same results as combining the pain drawing and symphyseal palpation. However, as the palpation test is very painful, it should be avoided if possible.

An observation by the testers was that the modified Trendelenburg test seemed to vary depending on if the subjects had time to pre-activate the stabilizing muscles before the leg lift. This indicates a need for further studies on the association of symphyseal pain and stabilizing muscles of the trunk.

Limitations in the study

Some of the pregnant women and non-pregnant women without pain were recruited from the author’s work place and from friends. This resulted in a large proportion of health care providers in the study. These women were, however, not familiar with tests used for diagnosing PGP. The majority of pregnant women without pain were recruited from one antenatal health care clinic. The variance of the sample is thereby limited and does not represent a normal population. A randomized selection would have been preferable.

Statistically significant differences were identified between groups regarding age and parity that may have influenced the result. The high sensitivity of the P4 test to the P4 self-test and the Bridging test may partly be explained by the fact that the pregnant women with pain were referred to a special clinic for PGP. If women with lower pain intensity had been included, the result might have been different. It would therefore be of value to investigate the accuracy of the modified self-tests in women with lower pain intensity.

A limitation of the tests is that it may be a problem for women to perform them correctly after only written instructions. It may for instance be difficult for the women to perform the P4 self-test with the hip in 90° flexion. The women performing the test in our study were supervised during the tests and corrected if necessary. It would be interesting to study if difference in performance could be of importance for the sensitivity, specificity, validity and reliability of the tests to see if the tests are valid also for women receiving only written instructions or only for those who have performed the tests previously under supervision.

It is desirable that the examiner is unaware of the patients’ presence of pain in a study of pain provocation tests to prevent preconceived ideas of test expectation. In the evaluation of pregnant and non-pregnant women without pain, only subjects without pain in lower back and the pelvic region were included, which might have interfered with the performance of tests.

One limitation of this study is that no repeated lumbar movements to end range were performed. This implies that women with discogenic pain might be present in the sample [12]. However, in a study of PGP, the women screening positive for PGP would be clinically thoroughly examined and could then be excluded if the pain had lumbar causes.

The subjects performed the self-administered tests before the tester did the confirmatory test. There is a possibility that the pain from the first provocation facilitated the second pain provocation. Performing the self-test and the confirmatory test on separate days would be an alternative. However, courses of pain may vary on different days and therefore this would not have been an optimal design either.

PGP and lumbar pain are probably two different syndromes as the clinical presentation and the course differ [6, 7, 22]. As women with lumbar pain were excluded, women with combined PGP and lumbar pain were excluded as well. This implies that the result of this study is generalized to women with PGP only.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that pregnant women can perform a screening of their posterior pelvic pain with the new P4 self-test and the Bridging test. Further evaluation of the self-test is required to be useful in questionnaire evaluations. Palpation of the symphysis is painful and should only be used as a complement to history taking, pain drawing and MAT-test.

References

- 1.Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s005860050228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:505–510. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080006505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG. Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Spine. 2002;27:2831–2834. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brynhildsen J, Hansson A, Persson A, Hammar M. Follow-up of patients with low back pain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:182–186. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook C, Massa L, Harm-Ernandes I, Segneri R, Adcock J, Kennedy C, Figuers C. Interrater reliability and diagnostic accuracy of pelvic girdle pain classification. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutke A, Ostgaard HC, Oberg B. Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study of the consequences in terms of health and functioning. Spine. 2006;31:E149–E155. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201259.63363.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutke A, Ostgaard HC, Oberg B. Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine. 2008;33:E386–E393. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817331a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen A, Jensen DV, Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Kaae BE, Frolich S, Thomsen HS, Hansen TM. Postpartum pelvic pain––the “pelvic joint syndrome”: a follow-up study with special reference to diagnostic methods. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen A, Jensen DV, Wormslev M, Minck H, Johansen S, Larsen EC, Wilken-Jensen C, Davidsen M, Hansen TM. Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnancy. II: symptoms and clinical signs. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:111–115. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2:1127–1131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristiansson P, Svardsudd K, von Schoultz B. Serum relaxin, symphyseal pain, and back pain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laslett M, Young SB, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Diagnosing painful sacroiliac joints: a validity study of a McKenzie evaluation and sacroiliac provocation tests. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mens JM, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Stam HJ, Snijders CJ. Understanding peripartum pelvic pain. Implications of a patient survey. Spine. 1996;21:1363–1369. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199606010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogren IM. BMI, pain and hyper-mobility are determinants of long-term outcome for women with low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson-Wikmar L, Holm K, Oijerstedt R, Harms-Ringdahl K. Effect of three different physical therapy treatments on pain and activity in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: a randomized clinical trial with 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up postpartum. Spine. 2005;30:850–856. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158870.68159.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noren L, Ostgaard S, Johansson G, Ostgaard HC. Lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy: a 3-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:267–271. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0357-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostgaard HC, Roos-Hansson E, Zetherstrom G. Regression of back and posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy. Spine. 1996;21:2777–2780. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199612010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostgaard HC, Zetherstrom G, Roos-Hansson E. The posterior pelvic pain provocation test in pregnant women. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:258–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02226575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostgaard HC, Zetherstrom G, Roos-Hansson E, Svanberg B. Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1994;19:894–900. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199404150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ransford A, Cairns D, Mooney V. The pain drawing as an aid to the psychological evaluation of patients with low-back pain. Spine. 1976;1:127–134. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197606000-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rost CC, Jacqueline J, Kaiser A, Verhagen AP, Koes BW. Prognosis of women with pelvic pain during pregnancy: a long-term follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:771–777. doi: 10.1080/00016340600626982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturesson B, Uden G, Uden A. Pain pattern in pregnancy and “catching” of the leg in pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain. Spine. 1997;22:1880–1883. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199708150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.To WW, Wong MW. Factors associated with back pain symptoms in pregnancy and the persistence of pain 2 years after pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:1086–1091. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0412.2003.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turgut F, Turgut M, Cetinsahin M. A prospective study of persistent back pain after pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;80:45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:794–819. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]