Abstract

Primary spinal malignant melanoma is an extremely rare condition. We here describe a case of a 71-year-old Asian female presenting with left upper extremity tingling sensation. Computed tomography (CT) showed a homogeneously enhanced mass occupying the left neural foramen at the C6-7 level. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed enhanced mass in intra- and extradural space compressing the spinal cord at this level. It also widened the neural foramen mimicking neurofibroma or schwannoma. Partial resection of the mass was performed. Pathologic diagnosis of the mass was malignant melanoma. Postoperative whole body positron emission tomography/CT scan demonstrated an intense 18F-FDG uptake at the residual mass site without abnormal uptake at other sites in the body.

Keywords: Primary malignant melanoma, Computed tomography, MR imaging, PET, Extramedullary intradural, Extradural, Cervical spine

Introduction

Primary malignant melanomas involving the central nervous system are unusual, and account for approximately 1% of all cases of melanoma [5]. Only a few cases of primary malignant melanomas limited to the cervical spinal nerve root have been reported. To our knowledge, there is only one previous report in the literature of cervical spinal malignant melanoma in intra- and extradural space [10]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) alone has been used for radiologic diagnosis in such cases. Furthermore, there appear to be no previous studies of such cases using positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging of the primary malignant melanoma. We present here a case of primary malignant melanoma in intra- and extradural space at the C6-7 level with CT, MRI, and PET/CT imaging findings and pathologic confirmation.

Case report

A 71-year-old woman presented with a 12-month history of left-sided motor weakness and radiculopathy. During the previous 2 months, the symptoms had progressively worsened. Upon neurological examination, she presented with numbness on the left C6 and C7 dermatomes. The neurological examinations were consistent with compression of the cervical cord and nerve roots.

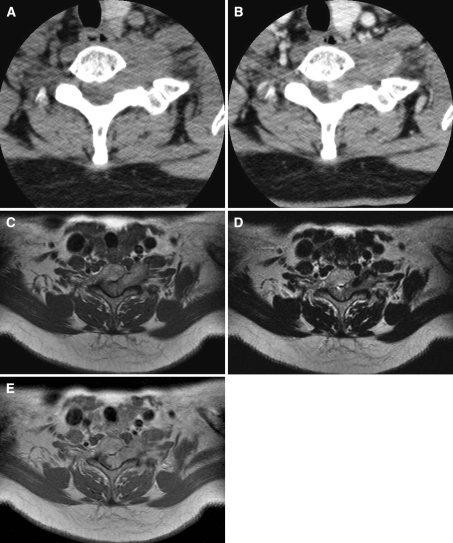

Non-enhanced CT of the cervical spine demonstrated a well-defined mass, located in the left-side neural foramen, with neural foraminal widening, at the C6-7 level. The lesion showed homogeneous iso-attenuation, compared with the adjacent skeletal muscle (Fig. 1a). After the intravenous administration of contrast material, the mass revealed mild heterogeneous enhancement (Fig. 1b). Cervical spinal MR imaging showed a well-demarcated, dumbbell-shaped mass of approximately 3.8 × 2.2 × 1.9 cm in size with neural foraminal widening in intra- and extradural space. On axial T1-weighted images, the mass revealed a hyperintense signal relative to the signal intensity of the spinal cord (Fig. 1c). Heterogeneous hypointensity was noted on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1d). There was a portion of dark signal intensity at the anterolateral aspect of the mass. After intravenous injection of a gadolinium-based contrast agent, a heterogenous enhancement of the lesion was noted (Fig. 1e). Preoperative clinical and radiological diagnosis was of neurofibroma or schwannoma.

Fig. 1.

a Non-enhanced axial CT demonstrates a well-defined mass with neural foraminal widening at C6–7. The mass shows similar homogenous density, relative to the skeletal muscle. b Contrast-enhanced axial CT shows heterogeneous, well-enhanced mass at same levels. c Axial T1-weighted image shows a dumbbell-shaped, homogeneous mass with slight hyperintensity, compared with the spinal cord at the C6–7 level. d Axial T2-weighed MR images show a slightly hypointense mass with a dark signal portion at the anterolateral aspect of the mass. e Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image show mild heterogeneous enhancement of the mass

The patient underwent partial resection of the mass. After total laminectomy, a dark encapsulated tumor was noted. It was firmly attached to the cervical nerve root and spinal cord. Intradural extension was noted. No clear limits of the tumor could be found in the intradural space. Postoperatively, her neuralgia was improved and the motor deficiency disappeared.

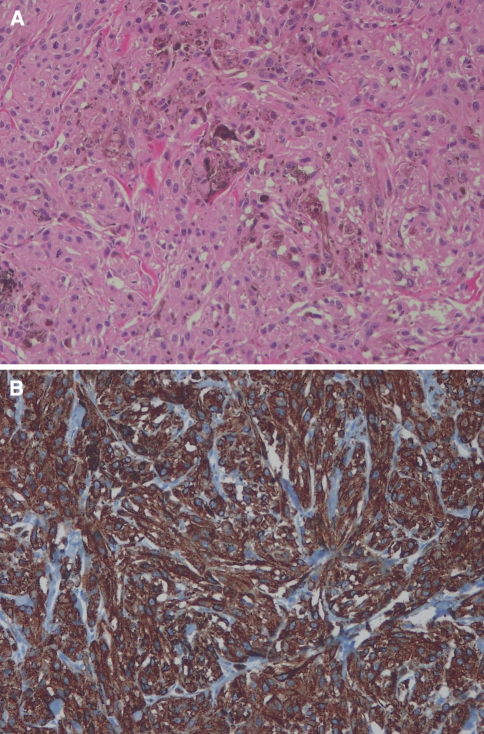

Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Histological analysis revealed highly cellular plump spindle cells and prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm was filled with compact melanosomes and several rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). There was no evidence of schwannian differentiation, such as external lamina and complex cytoplasmic processes. Strong immunohistochemical reactions for S100 protein and HMB45 confirmed the diagnosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a H&E (×200) shows the tumor consisted of clusters of tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm. The tumor cells had pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Melanin pigmentation was present. b HMB45 (×200) reveals that tumor cells showed positive reaction for HMB-45

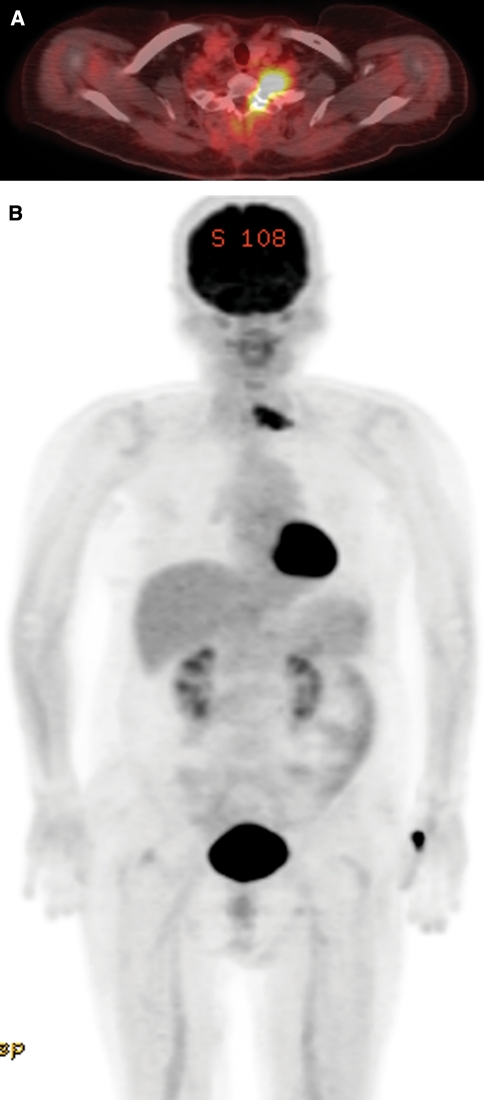

Because of relatively high prevalence of metastasis in pigmented tumor, we performed PET/CT for tumor staging procedure. Postoperative whole body PET/CT scan demonstrated an intense 18F-FDG uptake at the residual mass site, without abnormal uptake at other sites in the body (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PET/CT results. a Transverse fused PET/CT image shows intense FDG uptake in the mass of the left neural foramen at the level of C6–7. b Coronal maximum intensity projection image demonstrates FDG uptake at the tumor site, without abnormal uptake at other sites in the body. Normal physiologic intense FDG activity is seen in the brain, myocardium, and bladder. Note also the focal high accumulation of FDG in the left thumb region of the site of FDG injection

Discussion

Primary melanotic neoplasms of the CNS may arise from either melanocytes or Schwann cells, and they have a common embryological origin in the neural crest [9]. As a general rule, melanocytic tumors in the CNS are as a result of metastasis. Primary malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 1% of all CNS melanomas [2]. Several cases of primary spinal melanomas have been reported in the literature, including intramedullary, intradural, and extradural lesions [2]. To the best of our knowledge, only Skarli et al. [11] have reported case of primary melanoma arising in a cervical nerve root and involving the intradural portion. However, MRI alone was used for radiologic diagnosis in that case. We have presented here a primary malignant melanoma involving both intra- and extradural space in the cervical spinal neural foramen with PET/CT scan finding, as well as CT and MRI findings. The differential diagnosis of primary melanoma of the nerve root from schwannoma is extremely difficult because of the similarity in radiological findings, as well as its rarity. In general, spinal cord melanoma is usually revealed at high signal intensity on T1-weighted images. This is also the case at the same or lower signal intensities on T2-weighted images, relative to that of the spinal cord, using mild homogeneous enhancement [2]. The characteristic signal intensity of melanoma is thought to be caused by the paramagnetic susceptibility effect of the melanin pigment or hemorrhagic foci [6]. However, the different amounts of hemorrhage, differences in duration and degree of melanin in the malignant melanoma, may influence the variable of signal intensity from the tumor during MR imaging [2]. Thus, the differentiation of such a tumor from other malignancies is difficult. Therefore, final diagnosis is based on the results of pathologic examination. In our patient, the MRI findings were compatible with the previously reported characteristics in the literature. The region demonstrated dark signal intensity on T2-weighted images, suggesting a melanin or intratumoral hemorrhagic foci. Melanocytes arise from the neural crest during embryogenesis, and migrate to the skin, mucous membranes, and central nervous system [9]. It is important to differentiate primary melanoma from metastatic lesions, because primary malignant melanomas have a prognosis of better, long-term patient survival than have metastatic melanomas of the central nervous system [7]. Therefore, careful physical and radiological examination of the squamous mucosa, eyes, and skin, as well as of other CNS sites must be performed to exclude metastatic melanoma as a factor. In our patient, we could not detect any other tumor or pigmented skin outside of the CNS or other sites in the CNS, upon clinical and radiological examination, including PET/CT. The lesion was confirmed from pathological studies. Therefore, according to the Hayward classification criteria [3], our case was thought to involve a primary malignant melanoma.

Metabolic imaging with the radiolabeled glucose analog F-18-2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG)-PET has recently been shown to be a useful imaging modality for several malignancies, and is widely used in the staging and follow-up procedures for several types of cancer [8]. FDG accumulation in tumor cells is an increased expression of function and metabolic activity of glucose transporter proteins and of the glucose phosphorylating enzyme hexokinase in neoplastic tissues as well as metabolic trapping of FDG within the tumor cells because of the lack of further metabolic pathways for FDG [4]. In addition, distribution of FDG follow glucose utilizing cells and organs closely, there are several sites of normal physiologic FDG accumulation, including the brain, myocardium, urinary tract, brown adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, salivary glands, thyroid gland, and gonadal tissues. High level of FDG uptake can be detected in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum, because the brain is exclusively dependent on glucose metabolism. The myocardium has insulin-sensitive glucose transporters, and recent meal can increased FDG uptake in the myocardium. Contrary to glucose, only little tubular reabsorption, therefore, high FDG accumulation is seen in the intrarenal collecting systems, ureters, and bladder [4]. Some authors found PET to be highly accurate (91%) for diagnosing locoregional involvement of melanoma. Therefore, the whole-body PET scan may have a role as a staging procedure, because of the fact that melanoma may metastasize to anywhere in the body [1, 10, 12]. In our case, the whole-body PET/CT scan demonstrated an intense 18F-FDG uptake in the remaining mass, without FDG uptake in other sites in the body, suggestive of a primary lesion.

Because of the rarity of these lesions, the prognosis and the proper adjuvant therapies, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, have not been established yet [1, 6, 11]. We have presented here a rare case of primary malignant melanoma in intra- and extradural space at the C6–7 level. CT, MRI, and PET/CT scan findings were used, as well as CT and MRI findings, which confirmed by the pathologic examination.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fuster D, Chiang S, Johnson G, Schuchter LM, Zhuang H, Alavi A. Is FDG-PET more accurate than standard diagnostic procedures in the detection of suspected recurrent melanoma? J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1323–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrokh D, Fransen P, Faverly D. MR findings of a primary intramedullary malignant melanoma: case report and literature review. AJNR. 2001;22:1864–1866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayward RD. Malignant melanoma and the central nervous system. A guide for classification based on the clinical findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:526–530. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.6.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostakoglu L, Hardoff R, Mirtcheva R, Goldsmith SJ. PET-CT fusion imaging in differentiating physiologic from pathologic FDG uptake. Radiographics. 2004;24:1411–1431. doi: 10.1148/rg.245035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kounin GK, Romansky KV, Traykov LD, Shotekov PM, Stoilova DZ. Primary spinal melanoma with bilateral papilledema. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107:525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon SC, Rhim SC, Lee DH, Roh SW, Kang SK. Primary malignant melanoma of the cervical spinal nerve root. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:345–348. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihara M, Sasayama T, Kondoh T, Tanaka K, Kohmura E, Kudo H. Long-term survival after surgical resection of primary spinal malignant melanoma. Neurol Med Chir. 2009;49:546–548. doi: 10.2176/nmc.49.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbaum SJ, Lind T, Antoch G, Bockisch A. False-positive FDG PET uptake—the role of PET/CT. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1054–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider SJ, Blacklock JB, Bruner JM. Melanoma arising in a spinal nerve root. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:923–927. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.6.0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schöder H, Larson SM, Yeung HW. PET/CT in oncology: integration into clinical management of lymphoma, melanoma, and gastrointestinal malignancies. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:72S–81S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skarli SO, Wolf AL, Kristt DA, Numaguchi Y. Melanoma arising in a cervical spinal nerve root: report of a case with a benign course and malignant features. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:533–537. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199403000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner JD. A role for FDG-PET in the surgical management of stage IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:721–722. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.06.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]