Abstract

We report a case of 73-year-old man with massive hyperostosis of the cervical spine associated with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), resulting in dysphagia, hoarseness and acute respiratory insufficiency. An emergency operation was performed, which involved excision of osteophytes at the level of C6–C7, compressing the trachea against enlarged sternoclavicular joints, also affected by DISH. Approximately 3 years later, the patient sustained a whiplash injury in a low impact car accident, resulting in a C3–C4 fracture dislocation, which was not immediately diagnosed because he did not seek medical attention after the accident. For the next 6 months, he had constant cervical pain, which was growing worse and eventually became associated with dysphagia and dyspnoea, ending once again in acute respiratory failure due to bilateral palsy of the vocal cords. The patient underwent a second operation, which comprised partial reduction and combined anteroposterior fixation of the fractured vertebrae. Twenty months after the second operation, mild hoarseness was still present, but all other symptoms had disappeared. The clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of the two unusual complications of DISH are discussed.

Keywords: Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, Cervical spine fracture, Ankylosis, Acute respiratory failure

Introduction

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a degenerative disorder of unknown aetiology that most often occurs in patients over 50 and is associated with obesity, glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus [8]. DISH is a well-defined syndrome with axial and peripheral skeletal manifestations, including hyperostosis at tendon insertions and around joint capsules, and ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) of the spine [9]. Prominent osteophytes about the hips, symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints can often be found [7]. The majority of patients with DISH has a variety of insertional pain syndromes and need no surgical treatment. In rare cases of extensive ossification of the cervical spine, compression of the oesophagus and less often the trachea by ALL can lead to dysphagia, hoarseness, stridor and dyspnoea. Symptoms occur as a result of direct bony compression of the oesophagus. However, they may also be caused by compression neuropathy of laryngeal nerves [5].

Flexibility of the spinal column in DISH is markedly reduced as a result of ALL ossification. Ankylosis renders the spine susceptible to skeletal injury even after trivial trauma, cervical spine being most commonly affected [9, 13]. Spinal fractures are easily missed, because initial presentation may be limited to moderate pain without a neurological deficit [13]. Because of fracture instability, neurological deterioration usually occurs after a certain period of time. This is one of the main reasons why mortality rate in DISH patients with spinal fracture tends to be as high as 20% [13].

Case report

Part 1

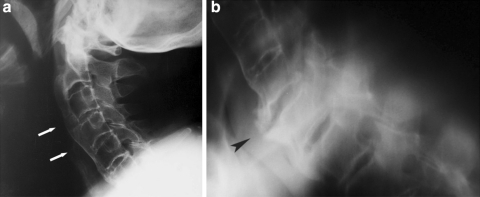

A 73-year-old obese man with type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and arterial hypertension was admitted to the Department of Pulmonary Diseases and Allergy with 2 months history of nocturnal dyspnoea, cough, stridor and hoarseness which worsened over last week. He was found to have slight normocytic anaemia and elevated CRP values (up to 24 mg/l). Lateral radiography of the cervical and thoracic spine revealed massive ossification of the ALL at the level of C2–C6 and large ventral osteophytes at the level of C6–C7 with marked compression of the trachea (Fig. 1a, b). CT of the thorax confirmed pronounced narrowing of the trachea at the level of sternoclavicular joints. Distal to the sternoclavicular joints, the trachea had a normal width (Fig. 2). The oesophagus was displaced to the left side. During the hospital stay, the patient developed acute respiratory insufficiency, requiring an emergency operation. Because of a difficult airway, awake fiberoptic intubation was performed. Following right cervicothoracotomy and partial sternotomy extending to the level of the third rib, massive anterior osteophytes were removed at the level of C6–C7, and the posterior parts of both enlarged sternoclavicular joints were resected. Because of marked intraoperative instability, segments C6 and C7 were fixed with a plate and screws.

Fig. 1.

Radiograph of the cervical and upper thoracic spine, lateral view, revealed massive ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament at C2–C6 (a) and large ventral osteophytes (arrowhead) at C6–C7 (b)

Fig. 2.

CT of the thorax confirmed pronounced narrowing of the trachea (arrowhead) caused by large ventral osteophytes at C6–C7 (arrow)

After the operation, the neck was additionally stabilized with a Philadelphia collar for 4 weeks. A postoperative CT scan of the neck revealed minimal residual compression of the trachea. The ENT consultant found partial palsy of the right vocal cord. At the time of discharge, some hoarseness was still present, but there was no dysphagia, dyspnoea or stridor. At the 2-month follow-up visit, the pulmonologist found neither hoarseness nor any other symptom or sign of respiratory dysfunction or air flow limitation.

Part 2

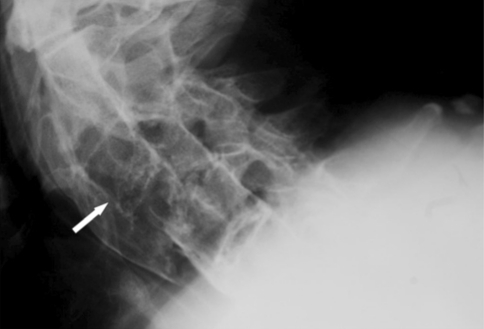

Thirty-seven months after the first operation on the cervical spine, the patient was involved in a posterior collision car accident on a parking zone, in which he probably sustained a whiplash injury. He did not seek medical attention after the injury, although he had a pain in his neck, which later grew worse. Six months after the accident, he was admitted to the ENT Department, complaining of hoarseness, dysphagia and dyspnoea. Radiography of the cervical spine showed a fracture dislocation at the level of C3–C4 (Fig. 3). The clinical status being stable, the initial treatment was conservative with a splint. Over the following week, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated, and he began to choke. On clinical examination, he was found to have bilateral palsy of the vocal cords requiring an emergency tracheotomy. A week after tracheotomy, he was seen by an orthopaedic surgeon, who established mild spastic tetraparesis due to the fracture dislocation of the cervical spine.

Fig. 3.

Radiograph of the cervical spine, lateral view, revealed a fracture dislocation at C3–C4, with anterior dislocation of C4 (arrow)

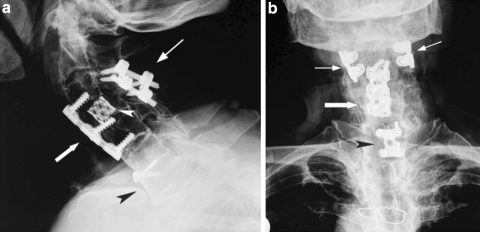

The patient underwent a second operation on the cervical spine, consisting of left-sided cervicotomy and partial resection of the body of C4, which made possible partial reduction of the fracture. A cage filled with autologous bone was inserted into the space between the bodies of C3 and C4, and the fracture was stabilized with a plate and screws, extending from C3 to C5. Additional posterior stabilization was achieved with lateral mass screws inserted at the level of C3–C4 (Fig. 4a, b). Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the ICU, where he was maintained on assisted ventilation for 2 days. The tracheostomy was closed on the fifth postoperative day. By the tenth postoperative day, the neurological deficit had resolved completely, and the patient was able to walk unaided. At discharge, 3 weeks after the operation, some hoarseness was still present, but stridor, dysphagia and dyspnoea had cleared completely.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative radiograph of the cervical spine: lateral (a) and antero-posterior views (b) show anterior stabilization of C3–C4 with a plate and screws (thick arrow) and lateral fixation with mass screws (thin arrow). Resected bone of the body of C4 was replaced by a cage filled with autologous bone (arrowhead). At C6–C7, anterior stabilization with a plate and screws (black arrowhead) was performed during the first operation

Twenty months after the second operation, additional diagnostic tests were performed to confirm the diagnosis of DISH and rule out ankylosing spondylitis, suggested in one of the previous radiographic reports. Clinical examination disclosed a stiff lumbar spine (Schober: 10/10.5 cm; finger to floor distance on forward bending: 16 cm). Spirometry revealed mildly restricted lung volumes. A chest expansion of 4 cm was measured at the fifth intercostal space. There were no neurological deficits; only mild hoarseness was still present. Laboratory tests revealed no anaemia (RBC 4.58, Hb 139) and no signs of inflammation (ESR 12, CRP < 3), but elevated glucose levels (up to 9.0). HLA-B27 was negative. Body mass index was 35.4. Radiography of the hips showed osteoarthritis on the right side and a total hip prosthesis on the left side (implanted due to osteoarthritis in September 2004), with huge heterotopic ossification around the greater trochanter and the acetabular ring. CT of the sacroiliac (SI) joints revealed ossification of the anterior joint capsule and anterior sacroiliac ligament. The cartilaginous parts of the SI joints were normal; there were no signs of erosion or sclerosis typical of ankylosing spondylitis. Cranially, within the ligamentous part of the SI joints, ossifications of interosseous ligaments were present (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

CT of the sacroiliac joints revealed normal cartilaginous parts with no signs of erosion or sclerosis (arrow). Cranially, ossifications of the interosseous ligaments were present (arrowhead)

Discussion

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis is a well-defined syndrome with axial and peripheral manifestation of hyperostosis. It occurs mainly in persons over 50 years of age, often in association with a metabolic disorder, such as glucose intolerance, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia or hypervitaminosis A [1, 12]. The prevalence, ranging up to 28%, increases with age [2] and presumably with weight [11]. For a long time, DISH was considered mainly a radiographic entity, while its clinical signs and symptoms received much less attention than those of other spinal diseases [6]. However, as pointed out recently by Mata et al. [4], DISH may cause considerable physical disability. Patients with DISH may have spinal pain of a mechanical type and a marked decrease in spinal mobility. These symptoms occur as a result of ossification of the ALL of the spine, which can lead to ankylosis of the neighbouring vertebrae. In the cervical spine, which is affected in 75% of patients with DISH [9], extensive ALL ossification can result in marked compression of anteriorly located anatomical structures. Usually the oesophagus is the first to be affected, followed by compression of the trachea and/or even direct entrapment of laryngeal nerves [5]. Symptoms resulting from massive anterior ossification include difficulty in swallowing, hoarseness, stridor and dyspnoea. In our patient, symptomatic airway compression occurred at the cervicothoracic junction, the trachea being compressed against enlarged sternocostal joints, also affected by DISH. The symptoms of airway obstruction appeared approximately 2 months before the development of acute respiratory distress. Airway decompression was performed as an emergency measure and was considered life saving. Based on this experience we recommend that diagnostic evaluation, including CT, in patients with massive cervical ossification be extended caudally to include the upper thoracic spine. Surgical treatment in patients with airway obstruction due to massive cervical hyperostosis should be undertaken as soon as possible.

Because of reduced flexibility of the spine in DISH, even minor trauma can cause spinal fracture, a condition seen most often in ankylosing spondylitis [9]. In such cases, pain can be mild and neurological deficits often nonexistent or subtle on initial presentation [13]. Therefore, injury is easily overlooked, visualization of the cervical spine on conventional radiographs being poor [10]. To avoid missing a fracture, high-resolution CT imaging of the cervical spine should be performed whenever a cervical spine injury is suspected in a patient with multilevel spinal ankylosis [3]. The second episode of acute respiratory failure in our patient, associated with a fracture dislocation at the level of C3–C4, was caused by bilateral paresis of the vocal cords due to entrapment of the laryngeal nerves. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute respiratory failure caused by laryngeal nerve entrapment in a fractured cervical spine affected by DISH. The risk of acute respiratory failure seems to be yet another hazard that calls for immediate recognition and urgent management of cervical spine fractures in DISH.

Conclusions

We describe a patient with DISH involving the cervical spine, who presented with two episodes of acute respiratory failure of different aetiology. The first was caused by massive osteophytes compressing the trachea at the level of C7–T1, and the second by a C3–C4 fracture dislocation, resulting in laryngeal nerve entrapment with vocal cord paresis. Both conditions were successfully managed with surgery.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Rok Vengust, Phone: +386-1-5224174, FAX: +386-1-5222474, Email: rok.vengust@kclj.si.

René Mihalič, Email: rene.mihalic@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Belanger TA, Rowe DE. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: musculoskeletal manifestations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:258–267. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boachie-Adjei O, Bullough PG. Incidence of ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine (Forestier’s disease) at autopsy. Spine. 1987;12:739–743. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrop JS, Sharan A, Anderson G, et al. Failure of standard imaging to detect a cervical fracture in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Spine. 2005;30:E417–E419. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000170594.45021.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mata S, Fortin PR, Fitzcharles MA, et al. A controlled study of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: clinical features and functional status. Medicine. 1997;76:104–117. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCafferty RR, Harrison MJ, Tamas LB, et al. Ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament and Forestier’s disease: an analysis of seven cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;83:13–17. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivieri I, D’Angelo S, Cutro MS, et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis may give the typical postural abnormalities of advanced ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1709–1711. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick D, Shaul SR, Robins JM. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH): Forestier’s disease with extraspinal manifestation. Radiology. 1975;115:513–524. doi: 10.1148/15.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shingyouchi Y, Nagahama A, Niida M. Ligamentous ossification of the cervical spine in the late middle-aged Japanese men: its relation to body mass index and glucose metabolism. Spine. 1996;21:2474–2478. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sreedharan S, Li YH. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis with cervical spinal cord injury—a report of 3 cases and literature review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005;34:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thumbikat P, Hariharan RP, Ravichandran G, et al. Spinal cord injury in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a 10-year review. Spine. 2007;32:2989–2995. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815cddfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utsinger PD. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Clin Rheum Dis. 1985;11:325–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vezyroglou G, Mitropoulos A, Kyriazis N, et al. A metabolic syndrome in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: a controlled study. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:672–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerveld LA, Verlaan JJ, Oner FC. Spinal fractures in patients with ankylosing spinal disorders: a systematic review of the literature on treatment, neurological status and complications. Euro Spine J. 2009;18:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0764-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]