Abstract

Pure spinal epidural cavernous angiomas are extremely rare lesions, and their normal shape is that of a fusiform mass in the dorsal aspects of the spinal canal. We report a case of a lumbo-sacral epidural cavernous vascular malformation presenting with acute onset of right-sided S1 radiculopathy. Clinical aspects, imaging, intraoperative findings, and histology are demonstrated. The patient, a 27-year-old man presented with acute onset of pain, paraesthesia, and numbness within the right leg corresponding to the S1 segment. An acute lumbosacral disc herniation was suspected, but MRI revealed a cystic lesion with the shape of a balloon, a fluid level and a thickened contrast-enhancing wall. Intraoperatively, a purple-blue tumor with fibrous adhesions was located between the right S1 and S2 nerve roots. Macroscopically, no signs of epidural bleedings could be denoted. After coagulation of a reticular venous feeder network and dissection of the adhesions the rubber ball-like lesion was resected in total. Histology revealed a prominent venous vessel with a pathologically thickened, amuscular wall surrounded by smaller, hyalinized, venous vessels arranged in a back-to-back position typical for the diagnosis of a cavernous angioma. Lumina were partially occluded by thrombi. The surrounding fibrotic tissue showed signs of recurrent bleedings. There was no obvious mass hemorrhage into the surrounding tissue. In this unique case, the pathologic mechanism was not the usual rupture of the cavernous angioma with subsequent intraspinal hemorrhage, but acute mass effect by intralesional bleedings and thrombosis with subsequent increase of volume leading to nerve root compression. Thus, even without a sudden intraspinal hemorrhage a spinal cavernous malformation can cause acute symptoms identical to the clinical features of a soft disc herniation.

Keywords: Cavernous malformation, Venous angioma, Spinal epidural mass, Acute radiculopathy

Introduction

Pure spinal epidural cavernous angiomas (PSECAs) not originating from the vertebral bone are rare with less than 100 reported cases [11]. They differ from hemangiomas of infancy, which are benign vascular tumors that usually regress spontaneously. Current classification defines PSECAs as congenital vascular malformations and not tumoral lesions [10]. Nevertheless, they bear a tendency to growth, and an essential feature of the natural biology of these benign hamartomatous vascular anomalies are acute bleedings with subsequent compression of the adjacent nervous structures within the spinal canal or the neural foramina. Local back or neck pain, radiculopathy, and myelopathy are typical sequelae of their increasing mass effect.

Case report

History

The 27-year-old male patient presented with acute onset of right leg pain radiating to the lateral aspect of the right foot, and the little toe. The symptoms had started suddenly during a longer car drive 48 h ago and pain intensity increased despite pain medication. Additionally, he noted continuous tingling and a feeling of numbness within the dorso-lateral aspects of the right leg that occured 24 h earlier. Back pain was absent. Neurological examination was inconspicuous. Except for a slight S1 hypästhesia on the right side, there was no motor deficit and no affection of the tendon reflexes. Because of the typical short history and the typical clinical presentation of a clear radicular S1 affection, an acute lumbosacral soft disc herniation was suspected.

Preoperative imaging

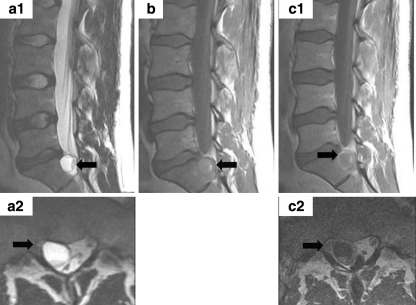

The contrast-enhanced MRI (Fig. 1) revealed a round cystic lesion within the right epidural space of the upper sacral canal. The content of this lesion consisted predominately of a light fluid in the middle and the top of the lesion with a T2 signal isointense and a T1 signal slightly hyperintense to the cerebrospinal fluid. Additionally, a second fluid level due to deposition of heavier particles at the bottom of the pathology was denoted. This minor content showed a T2 signal hypointense and a T1 signal hyperintense to the cerebrospinal fluid (a1, b: red arrow). The mass effect of the lesion led to compression of the right S1 nerve root (a2, c2: blue arrow). After Gadolinium administration, a solid ring enhancement (c1: orange arrow) indicative of a thick and circumscribed outer wall was observed.

Fig. 1.

Pure Cavernous vascular malformation, MR-imaging features: sagittal and axial T2 (a1, a2), sagittal T1 (b) and Gd enhanced sagittal and axial T1w MRI (c1, c2) demonstrates a cystic lesion with a fluid level (arrowa1, b) located posterior to the upper sacrum. The content predominantly consists of a fluid with deposition of the corpuscular blood particles at the bottom of the lesion. The lesion occupies the right half of the spinal canal and leads to compression of the right S1 nerve root (arrowa2, c2) laterally at the recess. Note the lesion’s circumscribed, relatively thick external wall that shows a ring enhancement (arrowc1)

The procedure

Because of the surprising imaging results the suspected diagnosis was changed from soft disc herniation to cavernous malformation. Resection of the pathology was performed via a microsurgical right lumbo-sacral fenestration as it is usually employed for removal of caudally dislocated sequestrae of the lumbosacral disc. Intraoperatively, a purple-blue tumor with strong fibrous adhesions to the dura and the posterior longitudinal ligament was found between the right S1 and S2 nerve root. No signs of fresh epidural bleedings were found and the lesion showed a relatively smooth surface with an elastic resistance during manipulation resembling a rubber ball. There was a reticular network of small epidural venous vessels predominantly arising from the attachment to the posterior longitudinal ligament. These feeders were fragile during manipulation and because of a tendency towards repeated and strong bleedings the intraoperative blood loss of 450 ml was relatively high for a microsurgical operation. After dissection of the fibrous adhesions to the dura and the nerve roots and intensive coagulation of the surrounding vessel network the lesion was resected in total. It had a diameter of 13 mm, an elastic resistance to pressure like a ballon, and appeared macroscopically like the aneurysma sack of an arterial vessel.

Histology

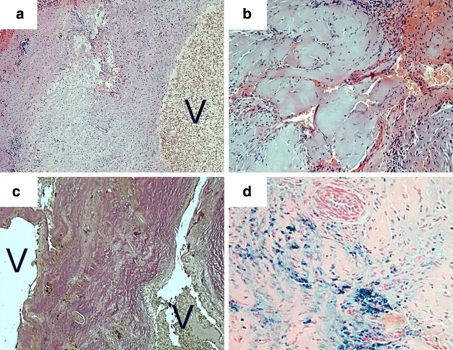

The specimen (Fig. 2) revealed a vascular malformation that contained a prominent venous vessel with a pathologically thickened, amuscular wall (a). This vessel was surrounded by a compact mass of smaller, hyalinized, venous vessels arranged in a back-to-back position typical for the histopathological diagnosis of cavernous angioma (b, c). Lumina were partially occluded by thrombi. The surrounding fibrotic and gliotic tissue showed signs of recurrent bleeding with fresh hemorrhage and segregation of the red and white blood cells as well as hemosiderin deposition (d). Vessels that had the media and the elastic laminae of arteries could not be detected within the malformation.

Fig. 2.

Cavernous vascular malformation, histopathological features: prominent venous vessel with an excessively thickened, amuscular wall (a, H&E). Hyalinized vessels (b, H&E) are arranged in a back-to-back fashion (c, Elastica van Gieson stain) as typical for cavernous angioma. Signs of recurrent hemorrhage with fresh bleedings (b) and residues of older bleedings in form of hemosiderin deposition (d, Berlin blue stain). Magnification of images a and c, ×100; magnification of images b and d, ×200; V vessel lumina

Outcome

Postoperatively the radicular leg pain vanished immediately, while the sensory deficits and the residual wound pain regressed completely within 6 days. A control MR scan was not done because the pathology was resected in toto. At the 6-month-control the patient was still without complaints.

Discussion

Although pure spinal epidural cavernous angioma (PSECAs) are rather vascular malformations than tumoral lesions they have a tendency to grow, and bleedings with subsequent compression of the adjacent nervous structures within the spinal canal or the neural foramina are typical for the natural biology of these benign hamartomatous vascular anomalies. Repetitive intra- or paralesional microhemorrhages usually lead to slow growth over years and intermittent or chronic progressive symptoms are the normal course of the disease [6, 10, 11, 14]. Thrombotic venous occlusion, compression of draining vessels, or sudden rupture of the amuscular wall with extralesional hematoma can lead to an acute increase in volume and sudden onset of clinical symptoms. Nevertheless, rapid clinical deterioration including sudden para- or tetraparesis generally is a rare event and usually caused by massive bleeding and compressive epidural hematoma [5, 7–9] or even intramedullary hematoma [4].

The typical clinical characteristics and imaging features of PSECAs have been evaluated by Aoyagi et al. [2] in review comprising a large series of 54 cases published between 1932 and 2001. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the diagnostic method of choice in PSECAs, and the normal appearance is that of a fusiform or lobulated epidural mass partially encircling the spinal cord. Most PSECAs were found in the thoracic spine (80%) and nearly all were located dorsally of the dural sack (93%), usually with lateral extension to the neuroforamina. MRI usually shows a T1 signal isointense to the spinal cord and a T2 signal isointense or slightly hypointense to the cerebrospinal fluid. There is always a homogeneous enhancement after gadolinium application, which becomes heterogeneous after recurrent bleeding [1–3, 10, 12–14].

The treatment of choice is a microsurgical total removal of the lesion. The recovery after complete resection of PSECAs is good to excellent in patients with slowly progressive clinical course. The rare patients with acute and severe clinical deterioration often suffer from permanent disability [2, 13].

The interesting features in the presented case are (1) the rubber ball like appearance of the cavernous angioma and (2) the clinical presentation with acute radiculopathy. (1) The normal shape of a pure spinal epidural cavernous angioma is that of a fusiform or multilobulated mass. In this case the lesion appeared as a perfectly round ballon with a thick elastic wall which had not yet been reported in the literature. (2) The acute onset of an S1 radiculopathy with leg pain and sensory deficit in a young and otherwise healthy man is usually pathognomonic for soft disc pathology. Obviously, our patient presented with an occult small cavernous angioma between the right S1 and S2 nerve root.

Histology revealed hemosiderin deposits as remnants of former microhemorrhages as well as fibrotic adhesions. While the mass effect of the lesion seemed not big enough to cause clinical symptoms in the past, now the lesion most likely experienced a sudden increase of volume due to a combination of intralesional thromboses and hemorrhage without rupture of the thick elastic wall. This is supported by histology, imaging, and intraoperative findings: Histology revealed lumina partially occluded by thrombi and fresh hemorrhage with segregation of the blood cells. The MRI showed a fluid level with deposition of the heavier blood cells at the bottom of the lesion. Intraoperative signs of a rupture of the cavernous angioma were absent: There was no epidural blood and the lesion exhibited an intact wall. Thus, most unusually, clinical symptoms in this patient were caused by the intact lesions sudden gain of volume, and not by rupture and extralesional hemorrhage.

Conclusions

Acute radiculopathy is caused by sudden mass effect usually because of soft disc herniation or in rare cases by spontaneous intraspinal hemorrhage. In very rare cases, a pure intralesional hemorrhage and thrombosis (without rupture) in an epidural cavernous angioma can lead to an acute increase in volume with subsequent nerve root compression.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Akiyama M, Ginsberg HJ, Munoz D. Spinal epidural cavernous hemangioma in an HIV-positive patient. Spine. 2009;9(2):E6–E8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyagi N, Kojima K, Kasai H. Review of spinal epidural cavernous hemangioma. Neurol Med Chir. 2003;43(10):471–475. doi: 10.2176/nmc.43.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlier R, Engerand S, Lamer S, Vallee C, Bussel B, Polivka M. Foraminal epidural extra osseous cavernous hemangioma of the cervical spine: a case report. Spine. 2000;25(5):629–631. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caruso G, Galarza M, Borghesi I, Pozzati E, Vitale M. Acute presentation of spinal epidural cavernous angiomas: case report. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(3):E575–E576. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255345.48829.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daneyemez M, Sirin S, Duz B. Spinal epidural cavernous angioma: case report. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2000;43:159–162. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal A, Singh AK, Gupta V, Tatke M. Spinal epidural cavernous haemangioma: a case report and review of literature. Spinal Cord. 2002;40(4):200–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jo BJ, Lee SH, Chung SE, Paeng SS, Kim HS, Yoon SW, Yu JS. Pure epidural cavernous hemangioma of the cervical spine that presented with an acute sensory deficit caused by hemorrhage. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47(6):877–880. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.6.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kivelev J, Ramsey CN, Dashti R, Porras M, Tyyninen O, Hernesniemi J. Cervical intradural extramedullary cavernoma presenting with isolated intramedullary hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8(1):88–91. doi: 10.3171/SPI-08/01/088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathews MS, Peck WW, Brant-Zawadzki M. Brown-Séquard syndrome secondary to spontaneous bleed from postradiation cavernous angiomas. AJNR. 2008;29(10):1989–1990. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagi S, Megdiche H, Bouzaïdi K, Haouet S, Khouja N, Douira W, Sebai R, Caabene S, Zitouna M, Touibi S. Imaging features of spinal epidural cavernous malformations. J Neuroradiol. 2004;31(3):208–213. doi: 10.1016/S0150-9861(04)96993-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satpathy DK, Das S, Das BS. Spinal epidural cavernous hemangioma with myelopathy: A rare lesion. Neurol India. 2009;57(1):88–90. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.48805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin JH, Lee HK, Rhim SC, Park SH, Choi CG, Suh DC. Spinal epidural cavernous hemangioma: MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25(2):257–261. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200103000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talacchi A, Spinnato S, Alessandrini F, Iuzzolino P, Bricolo A. Radiologic and surgical aspects of pure spinal epidural cavernous angiomas. Report on 5 cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1999;52(2):198–203. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(99)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zevgaridis D, Büttner A, Weis S, Hamburger C, Reulen HJ. Spinal epidural cavernous hemangiomas. Report of three cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;88(5):903–908. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.5.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]