Abstract

The goals of any treatment of cervical spine injuries are: return to maximum functional ability, minimum of residual pain, decrease of any neurological deficit, minimum of residual deformity and prevention of further disability. The advantages of surgical treatment are the ability to reach optimal reduction, immediate stability, direct decompression of the cord and the exiting roots, the need for only minimum external fixation, the possibility for early mobilisation and clearly decreased nursing problems. There are some reasons why those goals can be reached better by anterior surgery. Usually the bony compression of the cord and roots comes from the front therefore anterior decompression is usually the procedure of choice. Also, the anterior stabilisation with a plate is usually simpler than a posterior instrumentation. It needs to be stressed that closed reduction by traction can align the fractured spine and indirectly decompress the neural structures in about 70%. The necessary weight is 2.5 kg per level of injury. In the upper cervical spine, the odontoid fracture type 2 is an indication for anterior surgery by direct screw fixation. Joint C1/C2 dislocations or fractures or certain odontoid fractures can be treated with a fusion of the C1/C2 joint by anterior transarticular screw fixation. In the lower and middle cervical spine, anterior plating combined with iliac crest or fibular strut graft is the procedure of choice, however, a solid graft can also be replaced by filled solid or expandable vertebral cages. The complication of this surgery is low, when properly executed and anterior surgery may only be contra-indicated in case of a significant lesion or locked joints.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Fracture-dislocation, Anterior surgery, Upper cervical spine, Lower cervical spine

The last 20 years have shown an ongoing discussion whether anterior or posterior surgery is the treatment of choice for most of the cervical spine injuries. Attempts have been made to give either biomechanical, morbidity, simplicity of procedure or type of injury as reasons for the choice of treatment. All these arguments are valid and all taken together favour finally the anterior surgery, however, a lot of the decision, whether anterior or posterior surgery is chosen in the context of a cervical spine trauma, has to do with the surgeon’s preference.

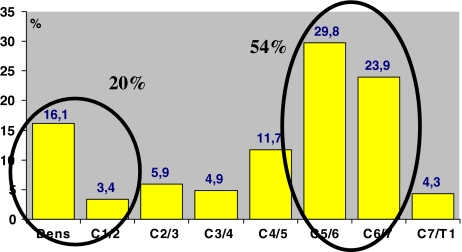

Looking at the distribution of acute cervical spine trauma 55% of the injuries is located at the level of C5/6 and C6/7 and approximately 20% are located at the level of the odontoid and the C1/2 level. The rest is more or less equally distributed over the whole cervical spine with a little preference for the level of C4/5 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of acute cervical spine trauma in 205 cases according to Blauth M, Innsbruck

While the anterior surgery at the level of C5/6 and C6/7 has become well established the approach at the upper cervical spine depends a lot from the type of injury. At the middle and lower cervical spine, the type of injury has only a subordinated role in the choice of the approach.

The goals of any treatment of cervical spine injuries be it surgically or non-surgically are return to maximum functional ability, minimum of residual pain, decrease of any neurological deficit, minimum of residual deformity and prevention of further disability.

There are some advantages of surgical treatment, which mostly are given by the ability to reach optimal reduction, immediate stability, direct decompression of the cord and the exiting roots, the need for only minimum external fixation, the possibility for early mobilisation and clearly decreased nursing problems. The question remains, how these goals and advantages can be reached. Is it through anterior or posterior surgery or even a combination of both?

In order to answer these questions there remain challenges:

Reduction of the injury: when and how?

Decompression: where, when and how? and

Stabilisation techniques: what kind of instrumentation?

One of the pre-requisite for an optimum treatment is reduction. Reduction is not only helpful for a simple surgical stabilisation procedure but also it is the best decompression. By anatomical reduction, the spinal cord usually is unloaded indirectly without doing a formal decompression procedure being a posterior laminectomy or an anterior decompression through excising the disc and possible fragments.

In more than 70%, a cervical spine injury can be reduced by traction only without any manipulation. According to the recommendations, usually the used weight for an optimum traction is 5–10% of the body weight or 5 pounds per level of injury (e.g. a lesion at the C6-level means 5 × 6 resulting in 30 pounds).

The simple traction can be applied through the installation of a Gardner–Wells tongue, which can be put on the head in the emergency room by any junior staff (Fig. 2). The placement of the pressure screws of the Gardner–Wells tongue is three fingers above the external auricular opening in line through this opening parallel to the table. If, the intention is to reduce in flexion with the traction, the entry point for these screws is a little bit in front of the mentioned line, if the intention is rather hyperextension, then the entry point is slightly behind this line. The traction manoeuvre needs to be monitored by X-ray or better by image intensifier to make sure that overdistraction does not occur. In a study in 1986, it has been demonstrated that one-third of the 60 patients with an incomplete tetraplegia showed a neurological improvement after early reduction. In 75% of these cases, the earlier reduction was performed within the first 6 h following the accident [1].

Fig. 2.

Entry point (asterisk) for the pins of the Gardner–Wells tongue (see text)

As demonstrated in animal experiments, it seems that also in the human, there is a time dependency of neurological recovery after the accident. Demonstrating the effect of the ‘trauma disease’ of the spinal cord after an injury, the damage to the spinal cord is today defined by the primary hit and damage to the cord and a secondary metabolic reactive change in the spinal cord [11].

Indications of anterior surgery in the upper cervical spine injuries

There are a variety of different injuries to the upper cervical spine some of them are rare. The most frequently encountered injuries are the odontoid fractures, the Jefferson fracture of C1, the C1/C2 dislocation due to a rupture of the transverse ligament of C1 and the traumatic spondylolysis of C2 with possible spondylolisthesis C2/C3 (Hangman fracture) [17].

The Jefferson fracture which is defined by a fracture of the arch C1 and disruption of the transverse ligament with an overall frontal widening of the arch by at least 7 mm with a dislocation in the joints C1/C2, can be treated either conservatively with a Halo or by a posterior or anterior transarticular screw fixation or as described recently through a transoral reduction and osteosynthesis of the arch C1 in the attempt to preserve the function in the joint C1/C2 [16]. Usually the complete reduction of this fracture by traction and translation, compression of the two fragments is insufficient.

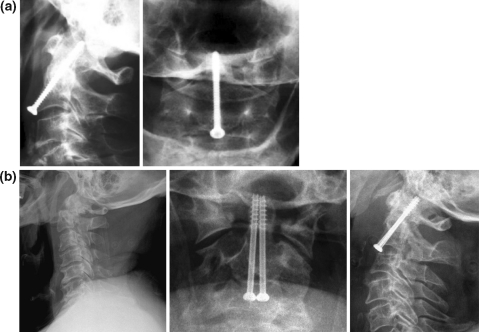

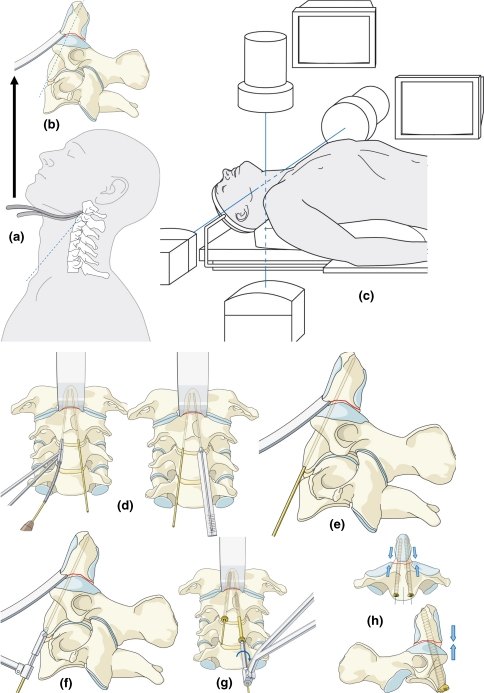

Out of the odontoid fractures, the type 2 is in most instances today a surgical indication. This is the fracture at the base of the odontoid process with dislocation of the process anteriorly or posteriorly or/and in rotation. The treatment of it is an anterior direct screw fixation of the dislocated fragment under traction and sometimes direct manipulation of the fragment transorally [2]. Sometimes, a direct screw fixation is not possible due to the shortness of the neck or the high up sternum. Then, it is not possible to incline sufficiently the direction of this screw. Also, in case of severe osteoporosis, it is advisable to use a posterior approach and fusion instead of putting a screw or two in the odontoid process. Most of the type 3 odontoid fractures may be treated conservatively with Halo, since the fracture surface is mostly cancelleous bone and the contact area quite big. In combined injuries of these odontoid fractures with dislocations in the joint C1/C2, an anterior direct screw fixation of the atlanto-axial joint may be an alternative [14, 18]. In the direct anterior odontoid screw fixation, some surgeons use just one screw and some use two screws [10, 13]. The advocates of two screws claim that by this procedure, the rotation can be better controlled (Fig. 3). The advantage of the anterior screw fixation is in the atraumatic approach and the possibility to operate the patient in supine position. The anterior screw fixation has initiated different screw technology one of them is cannulated screws over K-wires. In this latter case, once the K-wires are in proper position, the surgery is basically done [10] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Anterior odontoid screw fixation with a one screw and b two screws

Fig. 4.

a + b exposure of C2 and position of the Hohmann lever, c double image intensifier to have AP flat projection simultaneously available, d positioning of the pins and measuring, e lat. projection of the pin, f preparing the bed for the screw head, g insertion of screws, and h axial compression of the fracture AP + lat. view [4]

Complications of the odontoid screw fixation include malpositioning of these screws during surgery due to neglecting the recommended surgical principles and due to not using an AP and lateral X-ray monitoring. Screw pull out, specifically in osteopetrotic bone or when choosing the wrong entry point, may necessitate finally a combination with posterior surgery.

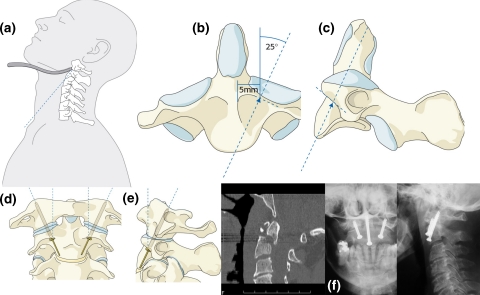

The odontoid non-union is a complication mostly of conservative treatment and usually due to an insufficient reduction of the fracture or overtraction. The treatment of odontoid non-unions can be quite challenging and, in most cases, is done by a posterior trans-articular screw fixation or fusion between C1 and C2, in extreme situations even between occiput and C2–C3. With the development of the anterior transarticular screw fixation, a combination of odontoid screw fixation with the anterior transarticular screw fixation can be chosen resulting in an atraumatic one approach surgery. The anterior transarticular screw fixation necessitates basically the same approach as an anterior direct odontoid screw fixation (Fig. 5a, b). This fixation technique is possible due to the specific anatomy of the C2/C1 joint (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Anterior transarticular screw fixation C2–C1. a Positioning of the Hohmann lever, b + c particular anatomical configuration for the entry of the screws, d + e positioning of the cannulated screws over K-wires and f case example [4]

Indications for the anterior approach in middle and lower cervical spine injuries

The anterior cervical spine surgery approach at the level of the C3 to T1 has been introduced in 1952 [6]. The addition of autologous’ bone graft for an intervertebral fusion has been proposed by Smith and Robinson in 1955 [20] and modified by Cloward in 1961 [9] and Verbiest in 1969 [21]. The anterior plate fixation has been first described by Böhler in 1964 [7] and has been developed by Orozco in Spain [12] and Sénégas in France [19]. At the beginning, standard AO-plates have been used, later in 1970 small fragment plates and in 1975 the so-called H-plate has been introduced (AO Spine Manual) [3].

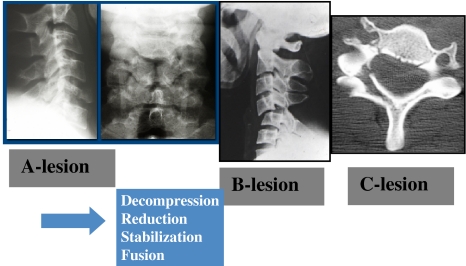

This concept has been modified in very different ways and today, there is a myriad of anterior plate systems available, but the basic principles remain the same. Since the late Seventieth, we have used the anterior plate fixation as a routine procedure and the posterior fixation in cervical spine injuries is only used in cases where anterior stabilisation cannot be performed. This is true independently from the type of lesion that means, whether there is an A-lesion with a purely anterior injury of the anterior column or whether there is a B-lesion with a predominantly posterior tension banding system damage with possible translational dislocation or hyperflexion dislocation. The same principles can be applied also in the C-lesions that means in the rotational injuries (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Typical lesions middle and lower CS. A-, B- and C-lesion

Laminectomies are almost never indicated in the cervical spine in the context of spinal cord trauma. Most of the cord compression is due to instability or dislocation of bone fragments, which come mostly from anteriorly and not from the back. Therefore, the compression of the spinal cord by bony fragments is the best treated by the anterior approach. The French orthopaedic surgeons have since long advocated also open anterior reduction [8]. This has been demonstrated successfully again in a recent paper by Reindl [15]. Only rarely and mostly in delayed cases, a posterior open reduction with an osteotomy of the facet joints or manipulation of the facet joints by instruments to reduce them, are necessary.

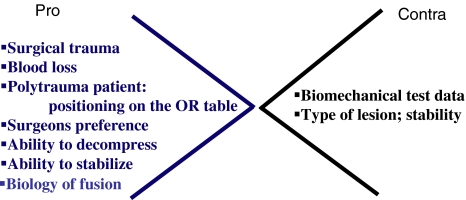

In terms of stabilisation, there is no doubt that all the biomechanical testing in the laboratory on cadavers support the superiority of the posterior instrumentation. However, there are clinical issues which support rather anterior surgery due to a minor surgical trauma, less bleeding, no need to position the patient in prone position on the table, optimal ability to decompress the spinal cord and good biomechanical conditions to put the fusion under compression. For the posterior surgery, speaks the better biomechanical test data in the cadaver, which may not necessarily be identical with the clinical need (Fig. 7] [5].

Fig. 7.

Clinical issues for or against anterior surgery in cervical spine trauma

Most of the results in the literature show that with an anterior surgery and proper application of a plate-bone construct can be reached in most instances. Complications have been advocated like dislodgement of implants, in most series reported below 5%. There is obviously a risk to penetrate the disc space or the spinal canal [1, 5, 15]. Inappropriate plate application in osteopetrotic bone may be another reason for implant failure.

In case of a completely comminuted vertebral body, a vertebrectomy may be necessary and the created defect can be filled easily by a tricortical bone graft or by even expandable small cervical cages.

Anterior surgery may be contra-indicated in case of significant posterior lesions compromising the spinal cord or roots or in clinically relevant dural leaks, in case of locked facet joints, which are unreducable by traction or even anterior open surgery, specifically, in case of delayed surgery. Furthermore, highly unstable injuries may need a combined anterior–posterior surgery or if an anterior stabilisation may appear insufficient intraoperatively. This may be the case in severely degenerated stiff C-spines creating a major lever arm on the traumatised segment.

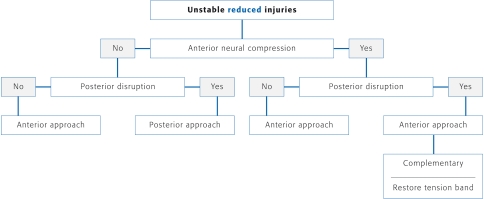

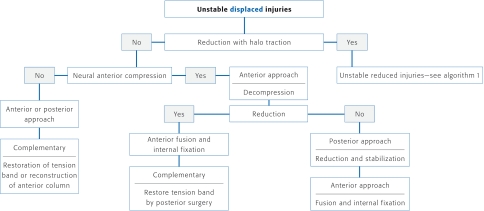

The procedure in traumatic cervical spine injuries is today quite standardised and outlined in the algorithm 1 (Table 1) and 2 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Algorithm 1 [3]

Table 2.

Algorithm 2 [3]

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Aebi M, Mohler J, Zäch G, et al. Indication, surgical technique, and results of 100 surgically-treated fractures and fracture-dislocations of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;203:244–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aebi M, Etter C, Coscia M. Fractures of the odontoid process. Treatment with anterior screw fixation. Spine. 1989;14:1065–1070. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aebi M, Webb J. The spine. In: Müller ME, editor. Manual of internal fixation. 3. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aebi M, Arlet V, Webb J (2007) AO spine manual, vol 1, Thieme Publishers

- 5.Aebi M, Zuber K, Marchesi D. The treatment of cervical spine injuries by anterior or plating. Spine. 1991;16:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey RW, Badgley GE. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg A. 1960;42:565–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böhler J, Gaudernak T. Anterior plate stabilization for fracture dislocation of the lower cervical spine. J Trauma. 1980;20:203–205. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bombart M, Roy Camille R, Castaing J, Derlon JY, Galibert P, Louis R, Saillant G, Sénégas J. Recent injuries of the lower cervical spine. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1984;70(7):501–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloward RB. Treatment of acute fractures and fracture-dislocations of the cervical Spine by vertebral-body fusion: a report of eleven cases. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:201–209. doi: 10.3171/jns.1961.18.2.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etter C, Coscia M, Jaberg H, et al. Direct anterior fixation of dens fractures with a cannulated screw system. Spine. 1991;16(3 Suppl):S25–S32. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geisler FH, Dorsey FC, Coleman WP. Recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with GM-1 ganglioside. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(26):1829–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106273242601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orozco Delcos R, Deldos R, Llovet TJ. Osteosysthesis en las fracturas de raguis cervical: nota de technica. Rev Ortop Traumatol. 1970;14:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pointillart V, Orta AL, Freitas J, Vital JM, Sénégas J, et al. Odontoid fractures: review of 150 cases and practical application for treatment. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(5):282–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02226580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reindl R, Sen MK, Aebi M. Anterior Instrumentation for traumatic C1-C2 instability. Spine. 2003;28(17):E329–E333. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000083328.27907.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reindl R, Quellet J, Harvey E, et al. Anterior reduction for cervical spine dislocation. Spine. 2006;12(6):648–652. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000202811.03476.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruf M, Melcher R, Harms J. Transoral reduction and osteosynthesis C1 as a function preserving option in the treatment of unstable Jefferson fractures. Spine. 2004;29(7):823–827. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000116984.42466.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaeren S, et al. et al. Upper cervical spine injuries. In: Aebi M, et al.et al., editors. AO spine manual clinical applications. New York: Thieme Stuttgart; 2007. pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen MK, Steffen T, Bechman L, et al. Atlanto-axial fusion using anterior transarticular screw fixation of C1/C2; technical innovation and biomechanical study. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(5):512–518. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0823-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sénégas J, Gauzière JM. In defence of anterior surgery in the treatment of serious injuries to the last 5 cervical vertebra. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1976;62(2 suppl):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith EW. The treatment of certain cervical spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40A(3):607–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verbiest H. Anterior-lateral operations for fractures and dislocations in the middle and lower parts of the cervical spine: report of a series of forty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg A. 1969;51(8):1489–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]