Abstract

Rheumatology nursing supports patients to manage their lives and live as independently as possible without pain, stiffness and functional restrictions. When conventional drugs fail to delay the development of the rheumatic disease, the patient may require biological treatment such as self-administered subcutaneous anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. It is therefore important that the patient perspective focuses on the life-changing situation caused by the administration of regular subcutaneous injections. The aim of this study was to describe variations in how patients with rheumatic diseases experience their independence of a nurse for administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy. The study had a descriptive, qualitative design with a phenomenographic approach and was carried out by means of 20 interviews. Four ways of understanding the patients' experience of their subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy and independence of a nurse emerged: the struggling patient; the learning patient; the participating patient; the independent patient. Achieving independence of a nurse for subcutaneous anti-TNF injections can be understood by the patients in different ways. In their strive for independence, patients progress by learning about and participating in drug treatment, after which they experience that the injections make them independent.

Keywords: Independence, patient, phenomenography, rheumatology nurse, self-administration, subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy

The intention of rheumatology nursing is to support patients to manage their lives and live as independently as possible (Ryan & Oliver, 2002), as well as to master their disease and improve their quality of life. The treatment of patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases is intended to minimise joint pain and swelling in order to reduce the risk of permanent joint damage and prevent functional impairment (Bykerk & Keystone, 2005). For the last 10 years, biological medications, of which some are specifically formulated to block the cytokine tumour necrosis factor-alfa (TNF-α), such as Remicade, Enbrel and Humira, have been used within rheumatology. These are administered either by the patient giving him/herself a subcutaneous injection or in a polyclinic by means of an intravenous infusion (Furst et al., 2010). Patients have a preference when it comes to administration method and should be given an opportunity to participate in such decisions. Subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy allows the patient to control his/her injections without extra cost to him/her and dispensing with the need for time to visit the hospital. Self-administered subcutaneous anti-TNF injections can be difficult for patients whose hands are deformed. The pre-filled syringes lead to limited flexibility in terms of dosage and thus there is a risk of non-adherence (Schwartzman & Morgan, 2004).

A goal of nursing care is well-informed patients who have sufficient knowledge to participate in decisions about their disease and treatment. It is important for nurses to strengthen patients' independence, thus allowing them to take responsibility for their own health (Hill, 2006). In a study by Larsson, Arvidsson S, Bergman, and Arvidsson B (2010), patients confirmed that information about medications provided by a nurse led to autonomy, power and security. Furthermore, patients have differing expectations of biological medications. Their experience of anti-TNF medications is that they increase physical and social functioning, reduce morning stiffness and pain as well as enhancing well-being and improving quality of life, especially in relation to increased physical ability that in turn leads to independence in everyday life (Davis, van der Heijde, Dougados, & Woolley, 2005; Marshall, Wilson, Lapworth, & Kay, 2004). The intravenous infusions involve regular contact with a nurse, which is conceived as secure, invigorating and leading to involvement. Security includes continuity, competence and information provided by a nurse. Patients report participation in the treatment as well as freedom in the sense that they do not have to attend to their medication between infusions and that the time at the hospital when the infusion is administered as invigorating as well as an opportunity to relax and rest in a calm environment (Larsson, Bergman, Fridlund, & Arvidsson, 2009). Due to the poor outcome of this treatment, only 36% of patients still receive intravenous anti-TNF infusions after 5 years (Kristensen, Saxne, Nilsson, & Geborek, 2006) and many start self-administration by means of subcutaneous injections (Keystone, 2006; Laas, Peltomaa, Kautiainen, & Leirisalo-Repo, 2008). Nevertheless, some express worries about what is to them a new and unknown medication and about administering the injections themselves (Marshall et al., 2004).

When developing the rheumatology care of those who are treated with biological medications, patients' needs should be the most important aspect. Jacobi, Boshuizen, Rupp, Dinant, and van den Bos (2004) emphasised the importance of the patient perspective for improving and adapting the care to patients' needs. Hill (2007) emphasised the need to educate patients and increase their knowledge of the treatment. When meeting “new” patients and assisting them to administer the therapy themselves, knowledge about the qualitative variation in patient needs could serve as a very powerful tool for rheumatologists and rheumatology nurses. It is therefore necessary to investigate how patients themselves understand the phenomenon of independence when their life situation involves regular administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. Schwartzman and Morgan (2004) argued that both the quantitative and qualitative investigations are required to study the two methods of administering anti-TNF medication. A literature review revealed no study that explored patients' conceptions of their independence of a nurse due to self-administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections in the field of rheumatology. A phenomeno-graphic study contributes to such knowledge, as it produces a variation in patient conceptions. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to describe variations in how patients with rheumatic diseases conceive their independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy.

Method

Design and method description

The study employed a qualitative descriptive design with a phenomenographic approach (Marton, 1981) in order to describe variations in conceptions of the phenomenon investigated. In order to grasp the variation in how patients experience their independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections, we need to understand what they experience differently. Phenomenography, which was chosen as the approach in this study, was developed in the early 1970s in Sweden within the domain of learning. It has since spread from the educational context to that of health science research (Sjöström & Dahlgren, 2002). The intention is to identify variations in conceptions of a specific phenomenon and to describe the qualitatively different ways in which a group of people makes sense of, experiences and understands the phenomenon in the world around them (Marton, 1981; Marton & Booth, 1997). The idea of variations in conceptions is important, because individuals will have different experiences depending on their various relationships to the world (Marton, 1992; Wenestam, 2000). It is important to be aware of conceptions relating both to our social reality and to ourselves. These two factors help to explain our everyday lives and the way in which we deal with them guide our opinion and direct our search for knowledge (Barnard, McCosker, & Gerber, 1999). Phenomenography places the focus on the analysis of the how aspect with the aim of identifying qualitatively different conceptions that cover the major part of the variation in a population. Several ways of understanding a phenomenon can be found in a group of people. Descriptions of what and how an individual conceives a phenomenon are not psychological or physical in nature, but concern the relationship between an individual and the phenomenon. These descriptions form descriptive categories, which are composed of a number of aspects of that which the participants experience in relation to the phenomenon (Marton & Booth, 1997).

Context

The study was based on interviews with patients conducted at a hospital in southern Sweden specialising in rheumatology diseases (Arvidsson et al., 2006). A nurse-led rheumatology unit handles parenteral biological medications for 225 patients who are prescribed subcutaneous treatment and 140 patients who receive intravenous infusions. The nurses provide patients with information about both subcutaneous and intravenous medications as well as support, monitoring and administration of the regular intravenous infusions. Patients who have opted to administer their biological medications by means of subcutaneous injections are allocated a personal support nurse after 1 or 2 months. Self-administration takes place once in a week or every other week depending on the medication prescribed.

Participants

The participants comprised of 20 patients undergoing self-administered subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy. In accordance with the phenomenographic tradition, the participants were strategically selected to obtain variation (Marton & Booth, 1997) with regard to sex (10 women, 10 men), age (17–79 years), civil status (eight single, 12 married/cohabiting), education (three primary school, 12 secondary school, five third-level education), employment status (12 employed, eight on sick leave or retired), duration of disease (1–42 years), length of treatment with the medication (0.25–10 years), previous treatment with intravenous infusions (seven patients) and being born outside Sweden (three patients).

Data collection

Data collection took place in the first half of 2009. The main author (IL), who works parttime as a nurse in a rheumatology clinic contacted the nurses in the nurse-led rheumatology unit in order to identify patients who met the study criteria. The patients selected for inclusion were asked whether they were willing to participate, and the nurses provided them with oral and written information about the aim of the study. When the patient had agreed to take part and signed the consent form, a time and place for the interview was decided upon in consultation with him/her. The patients were guaranteed confidentiality and informed that they could withdraw at any time without giving an explanation and without any consequences for their future care.

The interview started with the main author clarifying the aim of the study. An open interview guide with opening questions was employed as a means of ensuring that similar data were gathered from all patients (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). The following opening questions were used:

What does the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections involve for you?

How do you conceive the independence provided by the fact that you yourself can administer subcutaneous anti-TNF injections?

How do you conceive the fact that you are not dependent on a nurse for taking your anti-TNF injections?

In order to encourage the patient to probe more deeply into a question, he/she was asked to “tell more”, or questions such as “how do you mean?” or “what are you thinking of when you say…” were posed. Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 min, and was audio-taped. Two pilot interviews were conducted to check the questions. As no revision was necessary, these interviews were included in the analysis.

Data analysis

The aim of the phenomenographic method is to identify various ways of understanding a phenomenon (in this case patients' independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections). The analysis was performed by the main author and the fourth author (BA) acted as co-assessor. The main author transcribed the interviews as verbatim. The data analysis was performed in seven steps (Larsson & Holmström, 2007).

Reading the whole text several times, on the first few occasions in conjunction with listening to the audio-taped interviews.

Rereading the whole text, this time identifying and marking conceptions that corresponded to the aim of the study.

-

Searching for conceptions of what patients focus on and how they described their experiences of being independent of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. Formulating a preliminary description of each patient's dominant way of understanding his/her independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous injections (Figure 1). This can be illustrated by a quotation from the patient:

It's fantastic not to have to travel, because it takes time. It takes just a few minutes to make the necessary preparations here at home. You take out the syringe, pull it down and then administer it. So there is no problem. Otherwise you have to drive to the hospital or the district nurse, although I don't know if they [district nurses] do things like that, well I suppose they do. But it's good to be spared the trouble, and injecting myself is no problem.

Grouping the descriptions based on similarities and differences in meaning resulted in descriptive categories. These categories were compared in order to establish that each of them had a unique character and the same level of description. Quotations were selected in order to illustrate the connection between the participants' statements and the respective descriptive category.

-

Searching for non-dominant ways of understanding the phenomenon, i.e., statements in which the patients described other ways of understanding the phenomenon. This was undertaken to ensure that no aspect was overlooked (Figure 1). The following examples are from the same participant as above:

I had problems because we were going to South Africa and would be away for three weeks. And then my big problem was what to do with these syringes because they have to be stored in a cool place?

I phone if I think that I'm about to develop a cold and explain how I feel, in order to make certain about whether or not to take the shot. When you have a cold the nurses said that if the discharge is green then [one should not take the injection], but it's a bit tricky to tell, as you are a little afraid of doing the wrong thing. So I have phoned on one or two occasions and sometimes I did not take the injections until I was fully recovered.

Creating a structure out of the resulting descriptive categories, i.e., their outcome space. Together, the descriptive categories, the outcome space, constitute the result of a phenomenograpic study, which is reported in the form of text that is illustrated by means of anonymised quotations.

Assigning a metaphor for each descriptive category.

Figure 1.

Dominating (+ +) and non-dominating (+) ways of understanding how 20 patients with self-administered subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy experience their independence of a nurse. Figures in brackets: duration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injection (years).

Ethics

The study adhered to the four main requirements on research: information, consent, confidentiality and use (The Swedish Research Council, 2002). The participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time and given the opportunity to discuss any feelings and thoughts that had arisen during the interview. The regional Ethics Committee at Lund University approved the study (Grant No. 594/2008).

Findings

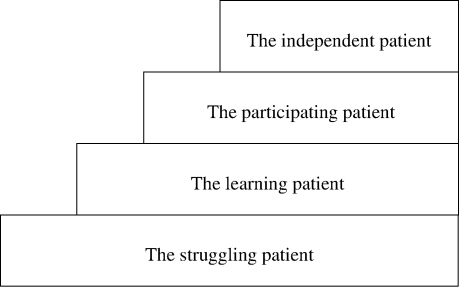

The following metaphors emerged from the four ways of understanding the patients' experiences of their subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy and independence of a nurse: the struggling patient; the learning patient; the participating patient; and the independent patient.

The numbers within brackets (No.) refer to a particular patient's statement.

The struggling patient

The patients experienced a struggle as well as limitations in their lives due to the self-administration of the subcutaneous injections. They strived to achieve independence and described being restricted by the injections. They worried that the injections would go wrong and missed the contact with a nurse. There was also a wish to be alone when administering the injections, as it was considered a private matter. The injections were painful and caused bruising, but the effect was good. They were grateful for this new, expensive medication. The subcutaneous injections meant a restriction in life, as they needed to be stored in a cool place, which created problems when travelling.

Now it's close in between, it's every week. I don't know, it's hard work actually. I have only one goal in life: to manage it myself. I don't want to become dependent on anyone. So I'm struggling on my own behalf. (No. 2)

The only problem is if you are going away somewhere for a longer period of time you have to bring it with you. That's always a problem. I was away once and brought a syringe with me but it was difficult, as it has to be kept cool and that's not always easy when you are travelling. (No. 4)

In this descriptive category, the conceptions were focused on the striving for independence. Injecting a medication into their own body and the pain involved gave rise to worry and influenced their motivation. There was a willingness to administer the subcutaneous injections themselves, as the result of the medication was good, but the discomfort it caused them made every injection a struggle between reason and emotion. “My brain wants me to do it, but not my hand”. The metaphor of the struggling patient emerged.

The learning patient

The patients experienced that self-administration of the subcutaneous injections was a learning process. Learning to administer the injections themselves increased their knowledge and competence. The patients experienced secure with this form of treatment, and their independence of others for the administration of their medication made them grow as human beings. When they needed information, they contacted a nurse and self-administration became a habit and a routine.

It's a habit. I have done so for many years now. (No. 7)

I do exactly as she (the nurse) showed me, wash and clean it sort of. That's what I've been taught to do and I don't do anymore than that. (No. 6)

Patients who described their independence of a nurse in the administration of subcutaneous injections in this way placed the emphasis on learning. They experienced increasingly secure in their self-administration of the medication, as their knowledge and competence improved with the training that repeated injections gave them. Self-administration became a routine and was carried out without reflection. “The things you know how to do are easy”. The metaphor of the learning patient emerged in this descriptive category.

The participating patient

Patients experienced control over their lives by administering the subcutaneous injections themselves. They took part in the treatment by self-administration and adhering to the prescription. Their involvement provided security both in terms of the treatment and their own decisions. They emphasised the importance of flexibility. Prescriptions and purchase of the medication required planning. In addition, correct disposal of the waste was highlighted as part of the treatment.

It feels good to be involved and not to be left out, like when they say: “I think you should do this” but instead they said: “There is a preparation that you might like to consider, and if so, you can read about it and then we can use it”. For my part I think it has been super, the fact that they never said: “I think you should take this”, but instead: “we have this, would you like to think about it?” Being given the opportunity to reflect on it. Then you are ready when it's time. (No. 11)

That I myself am involved, contribute to and influence how I feel. That's the implication of taking the shots because if I don't, I feel most unwell. (No. 10)

The focus of this descriptive category was patient participation in the form of treatment that provided independence. The most important aspect of participation was the decision to start self-administration and the practical tasks associated with the injections. Participation was interpreted as the opportunity to influence one's life by taking control of the administration of the injections as well as by complying with instructions. “I instantly took the decision that I was going to self-inject”. The metaphor of the participating patient emerged.

The independent patient

Patients experienced that they could manage their lives and live independently by administering the subcutaneous injections themselves. They stressed that managing the treatment gave them a feeling of freedom, which included independence of other people and not having to plan their lives according to appointments with a nurse. The responsibility for one's own treatment and thus one's own life was highlighted. The injections were easy to take and user friendly.

You have a complete new sense of freedom, you don't need to plan journeys, you do it when it suits you and you try to inject yourself on a Saturday or Sunday … It feels good for me because I don't need to plan my life according to appointments with a nurse. (No. 20)

It's a good thing that you can take the shot yourself and do it at home without the need to allocate extra time to go somewhere, and you might as well do it yourself as it's so simple. (No. 15)

The conceptions in this descriptive category focused on the freedom provided by self-administration. Independence of a nurse was conceived as liberating. The patients' lives were not governed by the administration of medication, which they controlled themselves. This meant autonomy and independence, which is a matter of course for those who do not need regular medication. “Self-injection makes you very independent; you are free to do what you want and to inject yourself at your leisure”. The metaphor of the independent patient emerged.

Outcome space

The qualitative analysis describes the different ways in which patients experience and manage their independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. The meaning of these different experiences can be identified by the researcher by the fact that they are related in certain ways, like the parts of a whole. Differences in the experiences of the phenomenon are merged together into four ways of understanding, which comprise the study's outcome space. These four ways of understanding represent the variation in the phenomeno-graphic analysis at a collective descriptive level and not the individual variation between patients. There were patients who moved between different dominant ways of understanding, while others retain the same level of understanding (Figure 1). Furthermore the meaning of the variation that emerged from the qualitative analysis is described as four different ways of understanding that are not hierarchically related, as they are more or less complex and developed (Marton & Booth, 1997). Instead, they can be regarded as a structure for describing variation and are illustrated as a staircase (Figure 2). The first way of understanding reveals how patients struggle to achieve independence of the nurse. This struggle can affect their lives to a greater or lesser degree. The second way focuses on learning, where the patients' knowledge and skills increase. The third way concerns participation in treatment and patient involvement that contributes to independence. The fourth way of understanding focuses on the patients' independence in the self-administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. Independence means that the patients have the ability to manage their lives and live independently. The relationship between the four different ways of understanding is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The outcome space illustrated by a staircase, representing the collective understanding of 20 patients' independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy.

Discussion

Independence of a nurse for regular subcutaneous anti-TNF injections can be understood in different ways. The patients are striving for independence when learning about and participating in their treatment, and the experience of being able to administer the injections themselves leads to a sense of freedom and independence. Patients can move between different ways of understanding as they experience various ways of becoming independent in terms of their subcutaneous anti-TNF injection therapy. The way of understanding how each individual patient finds him/herself is not related to how long they have been administering the injections themselves.

The results describe patients' conceptions of their independence of a nurse for subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy. The struggling patient strives for independence of a nurse and to administer subcutaneous anti-TNF injections him/herself. These patients want to be experts with respect to their own bodies and be respected for this. The possibility of not having to rely on other people is important for these patients, but they have to struggle for their independence, a finding supported by Ahlmén et al. (2005). They initially experience anxiety about their ability to administer subcutaneous injections themselves, which is linked to their awareness of the high cost of the medication also revealed in the study by Sanderson, Calnan, Morris, Richard, and Hewlett (2009). Any problems that arise during the initial period of self-administration can be resolved with support from the nurse. While most patients receive such support, rheumatology clinics nevertheless need to develop a follow-up of self-administration for individual patients (Brod, Rousculp, & Cameron, 2008). Patients who have regular contact with a nurse report a sense of security due to receiving support from him/her (Arvidsson et al., 2006; Larsson et al., 2009). Security evaporates when the patient becomes independent of the nurse and administers the medication him/herself. Thus, for patients, independence can also involve insecurity. The patients in our study described missing the contact with a nurse, when injecting themselves caused them pain and they had to struggle to administer the subcutaneous injection. This struggle is more or less apparent for patients during their treatment. The nature of the struggle varies, from dominating the patients' lives and restricting everyday activities, to minor limitations associated with keeping the syringes in a cool place while on holiday. The finding that the necessity to keep the medication cool restricts the patients' everyday lives is also supported by Hiley, Homer, and Clifford (2008), who hold that patients feel more independent and find it easier to travel when they do not have to worry about ensuring that their medications are stored in a cool place.

The learning patient increases his/her knowledge and competence, and learns how to manage a life that involves subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. The injections become a routine and thus a part of life. The patients reported that they obtained the necessary information and knowledge, and contacted the nurse at the rheumatology clinic on their own initiative when the need arose. A competent rheumatology nurse can support the patients during their learning process (Sanderson et al., 2009), although accessibility is an important factor (Larsson et al., 2010). Learning becomes a process in which basic knowledge is combined with actual experience, thus leading to a development in each individual patient, which Ingadottir and Halldorfsdottir (2008) also revealed to be relevant in the case of patients suffering from diabetes who administered subcutaneous injections on a daily basis. Regular subcutaneous injections form an integral part of the overall life situation of patients who require this type of therapy. Self-administered subcutaneous injections become a habit and routine for many patients and have a relatively limited subjective impact on their everyday life, which equally applies to patients suffering from HIV who also require injections on a daily basis (Cohen et al., 2003).

The participating patient takes part in his/her treatment in terms of the practical tasks involved in the administration as well as decisions related to the therapy. The patients wish to be involved in their drug treatment as supported by Chilton and Collett (2008). They should be encouraged to participate fully in the treatment of their condition (Hill & Reay, 2002) in accordance with Kjeken et al. (2006), who revealed that patients' ability to influence medical decisions needs to be further developed. Participation is important for patients with a rheumatic disease, as it contributes to security and control in their striving for a normal life (Sällfors & Hallberg, 2009). The level of participation varies and implies the need for trust, understanding and knowledge of their bodies, disease and treatment as well as providing control over the management of everyday life. Participation is characterised by respect for the individual and the fact that the patient is an active partner in planning the care (Eldh, Ekman, & Ehnfors, 2006). There were patients who rely totally on their doctor's knowledge and for them participation is of the greatest importance in decisions related to everyday life (Neame, Hammond, & Deighton, 2005). It is essential to encourage the patients to participate in as many treatment decisions as possible. When patients make a conscious decision, they experience a sense of control and their adherence to the treatment becomes greater, even when the effect of the medication is not immediately apparent (Ryan, 2006). Another factor that is important for adherence to the administration of subcutaneous medication is the patient's motivation (Brod et al., 2008).

The independent patient is capable of managing his/her life and medication. The freedom to care for him/herself and be independent of other people makes the patient's life easier. In society today, time is in short supply and it is thus extremely important to be able to cope with all aspects of life in a quick and easy manner. Ease of administration is of major importance for patients suffering from a rheumatic disease who require regular medication, which is supported by the patients in Chilton and Collett's (2008) study. Autonomy provides a sense of freedom. It is therefore vital to be independent and have self-control. The need for independence and autonomy is closely linked to the need for support and respect from other people, but also to responsibility and the ability to control one's treatment and thus one's everyday life. The need for independence differs between individuals, and therefore accessibility and sensitivity on the part of nurses are key factors for the provision of support. This also applies to other groups of patients with chronic diseases that are treated by means of regular subcutaneous injections, for example diabetes (Ingadottir & Halldorfsdottir, 2008). Patients who experience a positive effect from their subcutaneous anti-TNF injections obtain double freedom, as they can care for themselves and are independent of a nurse. When the treatment leads to elimination of the symptoms of their disease and the patients feel fit, they also experience freedom from pain, stiffness and sleep problems. They become independent in everyday life and feel like a “normal” person with an increased ability to cope with the various difficulties in life (Marshall et al., 2004). The design of the syringe makes it easy for the patient to administer the subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. This is in accordance with Sanderson et al. (2009), who hold that patients who administer their anti-TNF medication by means of subcutaneous injection are worried that they might have to change to intravenous infusions and thus become dependent on a nurse. In contrast, Larsson et al., (2009) described that patients treated by means of intravenous anti-TNF infusions reported a sense of freedom, despite being dependent on a nurse. In the latter case, the freedom involved not being obliged to take responsibility and not having to think about medication between infusion sessions (Larsson et al., 2009).

Reflection on the methodology

According to Polit and Beck (2010), the results of a qualitative study are assessed by means of four quality criteria: credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability.

In the data collection and analysis, credibility was strengthened by the use of an open interview guide, which was employed to assist the participant to reflect on the phenomenon of the independence of a nurse for the self-administration of anti-TNF injections from his/her own perspective. The main researcher asked the participant to reflect on his/her experience of the object of study and each participant was invited to explain his/her understanding in more detail. Follow-up questions were posed in order to avoid misunderstanding and the participants were encouraged to talk openly. The interview guide guaranteed that the same opening questions were posed to all participants. The interviews were conducted in an undisturbed location chosen by the participants. The main author was familiar with the subject area and conducted all the interviews. The fact that two pilot interviews were conducted and that no new dominant descriptive categories emerged after the 16th interview also strengthens credibility. Each conception was described by several participants, which also increases credibility. A characteristic of phenomenography is the search for variation, and every conception that emerges is relevant and important (Marton & Booth, 1997).

Dependability was strengthened by the fact that the data analysis sought to identify patients' dominant and non-dominant ways of understanding independence of a nurse in relation to subcutaneous anti-TNF injections. The main author attempted to be open to all variations in conceptions that corresponded to the aim. Dependability was also increased by the fact that the co-researchers were familiar with the method and that the researchers engaged in on-going discussions. The conceptions were compared and revised until the final classification was agreed on.

Confirmability of the results is considered relevant due to the way in which the data were systematically and carefully handled: repeated readings, identification and reflection on the resulting conceptions. All steps of the analysis have been conscientiously reported and confirmability is enhanced by the fact that the interviews were both conducted and transcribed by the main author. The conceptions are described in as much detail as possible and quotations strengthen and elucidate their content. The results reveal that, although the descriptive categories are positioned at the same contextual level, their meanings are clearly separate. The main author's pre-understanding can influence the results, because in her clinical work she meets patients who administer their subcutaneous anti-TNF injections themselves. An awareness of pre-understanding helped the researcher to bracket it, while the co-researchers did not possess such pre-understanding, thus the risk of influence was avoided. The researchers tried to be aware of their attitudes and be attentive to how these might affect their own interpretations. As a phenomenographic researcher, it is important to reflect on one's own interpretations, perspectives and values. It also means being open to the research and seeing research as a learning process. In a successful phenomenographic research process, the relationship between the researcher and the phenomenon being explored as well as the researcher's understanding of it develops.

In this study, transferability was strengthened by the method and recruitment process, which were intended to provide maximum information. Phenomenography is a method with high applicability for identifying variations in human conceptions of a phenomenon. In qualitative research, the meaning of applicability is that the study identifies and actually investigates that which it sets out to study. A strategic selection in line with the phenomenographic approach was made with the aim of obtaining maximum variation among the participants (Marton & Booth, 1997). Applicability can be deemed to be ensured due to the fact that the selection took account of several variables, such as sex, age, civil status, education, employment status, duration of disease, length of treatment with the medication, previous treatment with intravenous infusions and born outside Sweden. A limitation of the study may be that the participants only came from one hospital in Sweden. It is possible that the results might have been different had participants from other hospitals taken part, as it is likely that all hospital activities are not structured in the same way. However, in order for the material in a phenomenographical study to be manageable, the number of participants has to be limited (Larsson & Holmström, 2007). In this study 20 participants were relevant because the material was manageable and provided variation in conceptions. The results can be transferred to a wider group, provided that the strategic selection in this study represents the variation in the group and that patients at other hospitals are not in regular contact with a nurse for subcutaneous anti-TNF treatment.

Conclusion

The result of this study has provided insight into life with regular subcutaneous injections without the ongoing support of a nurse. Independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF injections can be understood in different ways and patients can move between various dominant ways of understanding. There is a struggle for independence, where patients improve their competence by learning and participating in drug treatment, after which they experience that self-administration of the subcutaneous injections provides independence. This knowledge can be used by the nurse in his/her work to support patients. The opportunity for regular contact with a nurse in the form of a nurse-led clinic for patients undergoing regular subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy might be one way of achieving security in terms of treatment. It would be interesting to investigate whether or not patients undergoing regular anti-TNF therapy experience increased security and participation by replacing every second visit to a doctor with a visit to a nurse.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from The Swedish Rheumatism Association.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors had no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ahlmén M., Nordenskiöld U., Archenholtz B., Thyberg I., Rönnqvist R., Lindén L., et al. Rheumatology outcomes: The patient's perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2005;44(1):105–110. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson B., Petersson A., Nilsson I., Andersson B., Arvidsson B., Petersson I., et al. A nurse-led rheumatology clinic's impact on empowering patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2006;8(3):133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard A., McCosker H., Gerber R. Phenomenography: A qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qualitative Health Research. 1999;9(2):212–226. doi: 10.1177/104973299129121794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brod M., Rousculp M., Cameron A. Understanding compliance issues for daily self-injectable treatment in ambulatory care settings. Journal of Patient Preference and Adherence. 2008;2(1):129–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykerk V. P., Keystone E. C. What are the goal and principles of management in the early treatment of rheumatoid arthritis? Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2005;19(1):147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton F., Collett R. Treatment choices, preferences and decision-making by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2008;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/msc.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C., Hellinger J., Johnson M., Staszewski S., Wintfeld N., Patel K., et al. Patient acceptance of self-injected enfuvirtide at 8 and 24 weeks. HIV Clinical Trials. 2003;4(5):347–357. doi: 10.1310/1W4A-R6MN-99Q4-1GNM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., van der Heijde D., Dougados M., Woolley M. Reductions in health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and improvements with etanercept therapy. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;53(4):494–501. doi: 10.1002/art.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldh A.C., Ekman I., Ehnfors M. Conditions for patient participation and non-participation in health care. Nursing Ethics. 2006;13(5):503–514. doi: 10.1191/0969733006nej898oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst D., Keystone E., Fleischmann R., Mease P., Breedveld F., Smolen J., et al. Update consensus statement on biological agents for treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2009. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(Suppl. 1):2–29. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiley J., Homer D., Clifford C. Patient self-injection of methotrexate for inflammatory arthritis: A study evaluating the introduction of a new type of syringe and exploring patients' sense of empowerment. Musculoskeletal Care. 2008;6(1):15–30. doi: 10.1002/msc.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. Patient education. In: Hill J., editor. Rheumatology nursing. A creative approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: Whurr Publisher Limited; 2006. pp. 435–458. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. The role of the rheumatology nurse specialist. Rheumatology in Practice. 2007;5(2):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J., Reay N. Rheumatology. The diagnosis, assessment and management of complex rheumatic disease. Nursing Times. 2002;98(9):41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingadottir B., Halldorfsdottir S. To discipline a “Dog”: The essential structure of mastering diabetes. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(5):606–619. doi: 10.1177/1049732308316346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C. E., Boshuizen H. C., Rupp I., Dinant H. J., van den Bos G. A. M. Quality of rheumatoid arthritis care: The patient's perspective. International Journal for Health Care. 2004;16(1):73–81. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keystone E. Switching tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: An opinion. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology. 2006;11(2):576–577. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeken I., Dagfinrud H., Mowinckel P., Uhlig T., Kvien T. K., Finset A. Rheumatology care: Involvement in medical decisions, received information, satisfaction with care, and unmet health care needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2006;55(3):394–401. doi: 10.1002/art.21985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen L. E., Saxne T., Nilsson J. A., Geborek P. Impact of concomitant DMARD therapy on adherence to treatment with etanercept and infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a six-year observational study in southern Sweden. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2006;8(6):R174. doi: 10.1186/ar2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S., Brinkmann S. InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laas K., Peltomaa R., Kautiainen H., Leirisalo-Repo M. Clinical impact of switching from infliximab to etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;27(7):927–932. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson I., Arvidsson S., Bergman S., Arvidsson B. patients' perceptions of drug information given by the rheumatology nurse. A phenomenographic study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2010;8(1):36–45. doi: 10.1002/msc.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson I., Bergman S., Fridlund B., Arvidsson B. patients' dependence on a nurse for the administration of their intravenous anti-TNF therapy: A phenomenographic study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2009;7(2):93–105. doi: 10.1002/msc.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J., Holmström I. Phenomenographic or phenomenological analysis: Does it matter? Examples from a study on anaesthesiologists' work. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2007;2(1):55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall N. J., Wilson G., Lapworth K., Kay L. J. Patients' perceptions of treatment with anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Rheumatology. 2004;43(8):1034–1038. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marton F. Phenomenography – describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science. 1981;10(2):177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Marton F. Phenomenography and “the art of teaching all things to all men”. Qualitative Studies in Education. 1992;5(3):253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Marton F., Booth S. Learning and awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Naeme R., Hammond A., Deighton C. Need for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A questionnaire survey. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;53(2):249–255. doi: 10.1002/art.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T. Essentials of nursing research. Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. The psychological aspect of rheumatic disease. In: Hill J., editor. Rheumatology nursing. A creative approach. Second edition. Chichester: Whurr Publisher Ltd; 2006. pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S., Oliver S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(20):45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson T., Calnan M., Morris M., Richard P., Hewlett S. The impact of patient-perceived restricted access to anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2009;7(3):194–209. doi: 10.1002/msc.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman S., Morgan G. J. Does route of administration affect the outcome of TNF antagonist therapy? Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2004;6(Suppl. 2):19–23. doi: 10.1186/ar996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sällfors C., Hallberg L. R-M. Fitting into the prevailing teenage culture: A grounded theory on female adolescents with chronic arthritis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2009;4(2):106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström B., Dahlgren L. O. Applying phenomenography in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;43(3):339–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Research Council. Ethical principles in humanistic-social science research. Stockholm: The Swedish Research Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wenestam C-G. The phenomenographic method in health research. In: Fridlund B., Hildingh C., editors. Qualitative research methods in the service of health. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2000. pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]