Abstract

Introduction: It is well-known that specific foods trigger migraine attacks in some patients. We aimed to investigate the effect of diet restriction, based on IgG antibodies against food antigens on the course of migraine attacks in this randomised, double blind, cross-over, headache-diary based trial on 30 patients diagnosed with migraine without aura.

Methods: Following a 6-week baseline, IgG antibodies against 266 food antigens were detected by ELISA. Then, the patients were randomised to a 6-week diet either excluding or including specific foods with raised IgG antibodies, individually. Following a 2-week diet-free interval after the first diet period, the same patients were given the opposite 6-week diet (provocation diet following elimination diet or vice versa). Patients and their physicians were blinded to IgG test results and the type of diet (provocation or elimination). Primary parameters were number of headache days and migraine attack count. Of 30 patients, 28 were female and 2 were male, aged 19–52 years (mean, 35 ± 10 years).

Results: The average count of reactions with abnormally high titre was 24 ± 11 against 266 foods. Compared to baseline, there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of headache days (from 10.5 ± 4.4 to 7.5 ± 3.7; P < 0.001) and number of migraine attacks (from 9.0 ± 4.4 to 6.2 ± 3.8; P < 0.001) in the elimination diet period.

Conclusion: This is the first randomised, cross-over study in migraineurs, showing that diet restriction based on IgG antibodies is an effective strategy in reducing the frequency of migraine attacks.

Keywords: migraine, food, diet, IgG, trigger

Introduction

The exact pathophysiology of migraine is still unclear. Besides different genetic mutations, there is evidence of a profound role of meningeal inflammation in migraine pathogenesis (1,2). Environmental trigger factors are thought to play an important role. Many contributing factors may trigger the occurrence of migraine attacks and food is one of the most well-known (3–8). These, however, as with most elements of migraine, need to be individualised to the patient with migraine.

Since the 1930s, hidden food allergy has been suspected to be linked to migraine. Several studies showed significant improvement when patients were put on an elimination diet (9–14). IgE-specific food allergy has been shown to be related with migraine supported by the success of individualised diet in controlling migraine attacks (4,15). Non-IgE antibody mediated mechanisms have also been proposed in food allergy (16). Aljada et al. (17) provided evidence for the pro-inflammatory effect of food intake. IgG antibodies against food antigens have been found to be correlated with inflammation and intima media thickness in obese juveniles (18). Several studies reported significant improvement in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) by food elimination based on IgG antibodies against to food antigens (19–22). Rees et al. (23) showed a beneficial effect of a diet guided by IgG antibodies to food in migraine patients. Recently, Arroyave Hernandez et al. (24) reported preliminary evidence that IgG-based elimination diets successfully controlled the migraine without need of medication.

Some foods (such as cheese, chocolate or wine) are thought to be one of the well-known reasons triggering of migraine attacks according to consistent reports from the patients. It has been reported that diet with low-fat intake could reduce the headache frequency and intensity (25). On the other hand, some additives (such as triclorogalactosucrose or aspartame) may trigger attacks in some migraineurs (4,26–29). However, it is neither easy nor very useful to organise routine diet according to robust protocols for many patients (3,30). All this indicates that there is a need for an individualised approach of the diet to relieve migraine. One has to distinguish between inflammation-induced migraine and migraine caused by food via other mechanisms such as histamine-induced vasodilatation.

IgG could be one of the markers to identify food which causes inflammation and could cause migraine attacks in predisposed individuals.

In this study, we aimed to test the beneficial effect of diet based on specific total IgG antibodies (subclasses 1–4) against 266 food antigens in controlling migraine in a double-blind, randomised, controlled, cross-over clinical trial.

Subjects and methods

Experimental protocol

This study was designed as a double-blind, randomised, controlled, cross-over clinical trial (31). After the approval of the hospital ethics committee, patients giving their written informed consent were recruited from headache out-patient clinic with the diagnosis of migraine without aura according to the criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition (32). For inclusion in the study, the patients should: (i) have had at least 4 attacks and 4 headache days per month within the last months; (ii) be aged 18–55 years; (iii) be treated with acute attack medications only or with preventive medications unchanged at least for 3 months; and (iv) be able to understand and co-operate with the needs of the study and the diet. The patients with suspected or clear-cut medication overuse, pure menstrual migraine or any other associated headache disorder were excluded.

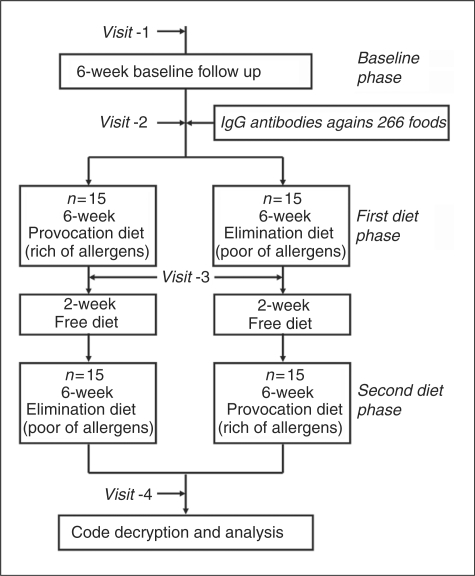

The study consisted of three main phases – baseline phase, first diet phase and second diet phase (Figure 1). In all phases, patients were asked not to change the dosages of their preventive medications if they were using any. The patients visited the same headache physician (first author, blinded to antibody test results and the order of the patient’s diet phases) during the whole study. At the first visit (Visit-1), the eligible patients recruited for the study were evaluated and asked to complete a headache diary for 6 weeks. The diary included headache attack frequency, headache days, attack duration in hours, attack severity in visual analogue scale (VAS) and medication information. During this 6-week baseline phase, the patients were followed in their usual daily diet. At the second visit (Visit-2) at the end of this 6-week baseline phase, the patients returned their diaries for evaluation and gave venous blood samples for detection of IgG antibodies against 266 food antigens (see Appendix 1) as described below. Then, the patients were allocated to one of the two 6-week diets based on a randomisation schedule either excluding (elimination diet) or including (provocation diet) specific foods with abnormally raised IgG antibodies, as described below. They were also asked to fill in a headache diary for 6 weeks. In this ‘first diet phase’, half of the patients were randomised to elimination diet and other half maintained provocation diet for 6 weeks. Neither the patients nor the headache physician knew if the diet was for elimination or provocation as well as IgG antibody test results. At the third visit (Visit-3) at the end of the ‘first diet phase’, the patients returned their diaries for evaluation. Then, the patients were allowed to return to their usual diets for 2 weeks without keeping diary. In ‘second diet phase’ following this 2-week diet-free interval, the patients who were on elimination diet in the ‘first diet phase’ were given provocation diet for 6 weeks and vice versa. They were asked to fill a headache diary for 6 weeks during the second diet phase. At the fourth visit (Visit-4) following the ‘second diet phase’, diaries were recollected and the diet codes were broken. Patients were informed about their results and the order of the types of their diets.

Figure 1.

Cross-over design of the study.

IgG antibody detection against food antigens

IgG antibodies against 266 food antigens were detected using a commercially available enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) test (ImuPro 300 test; Evomed/R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany), previously used by Wilders-Truschnig et al. (18) IgG calibration was performed against the international reference material 1st WHO IRP 67/86 for human IgG. Quantitative measurements are reported in mg/l. Detection limit was 2.5 g/l, normalised cut-off value was 7.5 mg/l, according to the validation protocol provided by the manufacturer. All values above 7.5 mg/l were considered as positive reaction to the corresponding food. Positive reaction was graded as: ‘low’ for titres between 7.50–12.50 mg/l; ‘moderate’ for 12.51–20 mg/l; ‘high’ for 20.1–50 mg/l; and ‘very high’ for 50.1–200 mg/l. Since IgG antibodies against food disappear within 3 months to 2 years depending upon initial titre, antibody detection was not repeated after the diet phases which were not long enough to see any change in antibody titres.

Diet preparation

Diets were arranged according to the IgG antibody results; eating habits for individual patients were taken into account and patients were educated about keeping diet by a dietician (DKU, co-author). Diets were assembled by this dietician, trying to offer a nutritionally balanced diet. The elimination diet consisted of a defined panel of IgG-negative food, while the provocation diet consisted in a panel of IgG-positive food and IgG-negative food necessary to comply with a balanced diet. Both elimination diet and provocation diet did not differ in calorie content. Patients were not allowed to eat any other food as specified by the dietician. In both diet phases, patients were never forced to eat or avoid from certain foods to protect the blindness of patients and their physician for the type of diet phase (elimination or provocation). Instead, they were asked to follow their specially arranged diet list exactly and not to consume any other food in any diet phase.

Statistical analysis

The primary parameters used for comparisons were number of headache days, migraine attack count, mean attack duration, median attack severity (in VAS score from 0–10), number of migraine attacks with acute medication and total medication intake within 6-week periods of each three phases. Statistical analyses included parametric tests to compare means (paired and unpaired two sample t-test), non-parametric tests to compare medians (Wilcoxon test and Mann–Whitney test) and 2 × 2 chi-square test. For comparisons between baseline phase and provocation phase or between baseline phase and elimination phase or between provocation phase and elimination phase, both paired t-tests (parametric test and Wilcoxon signed test as non-parametric test) were used. For comparisons between patients whose first diet phase was elimination diet and patients whose second diet phase was elimination diet (to test the ‘period effect’), both unpaired t-tests (parametric test and Mann–Whitney unpaired test as a non-parametric test) were used.

Results

A total of 35 patients were recruited for the study. In the baseline phase and the first diet phase, five patients withdrew from the study for different reasons, such as moving to another city, unwillingness to maintain diet or skipping the visit. The remaining 30 patients fully completed the study. Of these 30 patients, 28 were females and 2 were males. Ages varied from 19 years to 52 years (mean, 35 ± 10 years). Their mean migraine duration was 13 ± 9 years (range, 1–30 years). All 30 patients were using acute attack medication for migraine attacks and 15 were also using preventive medication. From the IgG antibody tests against to 266 food allergens, mean reaction (abnormally high titre) count was 24 ± 11 (7–47 reactions in individual patients). Of the total 732 reactions, 297 (40%) were low, 337 (46%) were moderate, 70 (10%) were high and 28 (4%) were very high graded. The food categories are listed in Table 1 from the most frequent IgG positivity to least.

Table 1.

The food categories from most frequent IgG positivity to least

| Number of patients with positive test result (n = 30) | |

|---|---|

| Spices | 27 |

| Seeds and nuts | 24 |

| Seafood | 24 |

| Starch | 22 |

| Food additives | 21 |

| Vegetables | 21 |

| Cheese | 20 |

| Fruits | 20 |

| Sugar products | 20 |

| Other additives | 14 |

| Eggs | 14 |

| Milk and milk products | 14 |

| Infusions | 13 |

| Salads | 10 |

| Mushrooms | 9 |

| Yeast | 5 |

| Meat | 5 |

The parameters of headache and medication are shown in Tables 2 and 3. In the elimination diet period compared to both baseline period and provocation diet period, there was a statistically significant reduction in attack count, number of headache days, number of attacks with acute medication and total medication intake whilst no significant change occurred between the provocation diet period and the baseline period (Table 2). However, attack severity and attack duration did not change significantly between all three phases (Table 2). By comparing percentage differences from baseline, in the elimination diet period, attack count, number of headache days, number of attacks with acute medication and total medication intake showed significant reduction compared to the provocation diet period (Table 3). To test the effect of order of diet, patients were divided to two subgroups: 15 patients with elimination diet in the ‘first diet phase’ and 15 patients with elimination diet in the ‘second diet phase’. We calculated the differences (in both real numbers and percentage differences) between the elimination diet period and the baseline, provocation diet period and baseline and elimination diet period and provocation diet period for attack count, number of headache days, number of attack with acute medication, total medication intake, median attack severity and mean attack duration for each subgroup. In none of these parameters, did the two subgroups show any significant difference in any of these comparisons, indicating that, whether the elimination diet was in the first diet phase or second diet phase, the order of elimination diet period had no significant effect on the outcome (Table 4). Similar calculations were made for preventive medicine usage and there was no significant change in any parameters between preventive medicine users (n = 15) and non-users (n = 15).

Table 2.

Headache and medication parameters during study phases

| Phases, each of 6

weeks ± SD (95%

CI lower; upper limits) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Baseline | Provocation diet | Elimination diet |

| Attack count | 8.97 ± 4.4 (7.32; 10.61) | 8.13 ± 4.6 (6.43; 9.83) | *6.17 ± 3.8 (4.67; 7.58) |

| Number of headache days | 10.53 ± 4.4 (8.90; 12.17) | 10.20 ± 5.5 (8.15; 12.25) | *7.47 ± 3.7 (6.08; 8.85) |

| Number of attacks with acute medication | 6.73 ± 2.9 (5.65; 7.81) | 6.53 ± 4.0 (5.05; 8.01) | †4.90 ± 3.2 (3.69; 6.11) |

| Total medication intake (tablets) | 11.37 ± 7.4 (8.61; 14.13) | 10.57 ± 7.7 (7.69; 13.44) | ‡7.77 ± 5.7 (5.65; 9.89) |

| Median attack severity (VAS) | 6.02 ± 1.6 (5.42; 6.62) | 6.07 ± 1.6 (5.47; 6.66) | 6.07 ± 1.6 (5.60; 6.77) |

| Mean attack duration (hours) | 11.39 ± 5.6 (9.30; 13.48) | 12.53 ± 6.7 (10.04; 15.03) | 12.53 ± 6.7 (9.57; 15.14) |

*P < 0.001/P < 0.001; †P < 0.001/P = 0.001; ‡P = 0.002/P = 0.001 in Paired t-test/Wilcoxon signed test (with 95% confidence intervals) comparing elimination and baseline diet phases (differences are statistically significant).

Table 3.

Percentage difference of parameters from baseline period

| Parameters | Provocation diet* (% difference) mean ± SD (95% CI limits†) | Elimination diet* (% difference) mean ± SD (95% CI limits†) | P-values‡ paired t-test/ Wilcoxon test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attack count | −7.81 ± 37.6 (−21.85; 6.23) | −29.11 ± 26.0 (−38.83; −19.39) | P = 0.006/0.004 |

| Number of headache days | −2.77 ± 35.2 (−15.93; 10.38) | −25.68 ± 30.9 (−37.22; −14.13) | P = 0.006/0.006 |

| Number of attacks with acute medication | 3.49 ± 66.4 (−21.30; 28.29) | −20.50 ± 54.2 (−40.74; −0.27) | P = 0.006/0.002 |

| Total medication intake (tablets) | 7.34 ± 67.0 (−17.68; 32.35) | −16.33 ± 56.6 (−37.41; 4.75) | P = 0.006/0.006 |

| Median attack severity (VAS) | 5.12 ± 33.3 (−7.33; 17.56) | 8.15 ± 42.0 (−7.53; 23.82) | NS (P = 0.348/0.460) |

| Mean attack duration (h) | 25.19 ± 81.6 (−5.29; 55.67) | 12.79 ± 53.3 (−7.10; 32.68) | NS (P = 0.442/0.738) |

*Percentage difference from baseline period; †(lower; upper) limits of 95% confidence interval; ‡P-values with 95% confidence interval; NS, not significant.

Table 4.

Percentage difference of elimination diet parameters from baseline period between the groups starting with elimination diet and starting with provocation diet

| Elimination diet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | At 1. Diet* (% difference†) median value (percentiles‡) n = 15 | At 2. Diet** (% difference) median value (percentiles) n = 15 | P-value (Mann–Whitney unpaired test) |

| Attack count | −37.5 (−55.6; −20.0) | −30.0 (−35.0; −16.7) | NS (P = 0.367) |

| Number of headache days | −30.0 (−50.0; 0.0) | −33.3 (−46.2; 0.0) | NS (P =0.902) |

| Number of attacks with acute medication | −37.5 (−55.6; 0.0) | −30.0 (−50.0; 0.0) | NS (P = 0.653) |

| Total medication intake (tablets) | −25.0 (−65.2; 20.0) | −18.2 (−37.9; 0.0) | NS (P = 0.539) |

| Median attack severity (VAS) | 0.0 (0.0; 14.3) | 0.0 (−20.0; 14.3) | NS (P = 0.512) |

| Mean attack duration (h) | 10.9 (−29.0; 74.9) | 3.7 (−27.3; 13.0) | NS (P = 0.267) |

*Patients starting with elimination diet; **patients starting with provocation diet; † percentage difference from baseline period; ‡(25%; 75%) percentiles.

NS, not significant in Mann-Whitney test with 95% confidence interval.

We also calculated if the patient showed at least a 30% reduction and at least a 50% reduction for attack count and number of headache days using elimination diet compared to provocation diet and to the baseline period. In comparison between elimination and baseline phases, for parameters of the number of headache days and attack count, reduction was ≥30% in 16 (53%) and 16 (53%) patients, respectively, and reduction was ≥50% in 7 (23%) and 6 (20%) patients, respectively. In comparison between elimination and provocation phases, for the number of headache days and attack count, reduction was ≥30% in 15 (50%) and 12 (40%) patients, respectively, and reduction was ≥50% in 6 (20%) and 4 (13%) patients, respectively.

Discussion

The concept that food may trigger some symptoms creates an increasing pressure on the healthcare system to investigate possible causal relationships between food intake and specific diseases. In the case of migraine, it seems evident that food is not the primary cause but, via different mechanisms, is able to induce or aggravate migraine attacks. In some individuals, the consumption of chocolate or red wine is enough to provoke an attack; whereas, in others, a combination of food is required, even sometimes with food which has never been related to migraine for other migraineurs. However, it is neither easy nor very useful to organise routine diet according to robust protocols for many patients (3,30). All this indicates that there is a need for an individualised approach to diet to relieve migraine.

A recent study addressed a relationship between IgG antibodies against food antigens and systemic inflammation measured by C-reactive protein (CRP) in obese juvenile patients (18). Obesity was also shown as an important risk factor in the development of chronic daily headache and chronic migraine (33,34). The therapeutic potential of dietary elimination on the basis of the presence of IgG antibodies against food in patients with IBS has been investigated. Patients were randomised to receive either a diet excluding all foods to which they had raised IgG antibodies or a sham diet excluding the same number of foods but not those to which they had antibodies (19). The true diet resulted in a statistically significant reduction in symptom scores compared to the sham diet and the authors concluded that this technique is worthy of further clinical research in IBS.

There is growing evidence that inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of migraine (2). The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and nitric oxide (NO) may participate in immune and inflammatory responses. Some patients report that certain foods only trigger migraine in conjunction with stress or extended physical exercise. Both conditions, recognised as triggers of migraine, cause the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In these cases, inflammation caused by food could create the pro-inflammatory milieu necessary for the induction of migraine by other triggers. If we focus on inflammation induced by food, a specific marker is needed. All IgG subclasses, except IgG4 lead to an inflammatory response when in contact with the respective antigen. Determination of specific IgG to a large number of foods is an ideal tool to detect individually suspected food and enables a modification of nutritional habits in order to prevent chronic inflammation and onset of migraine in sensitised patients. Susceptibility to other triggers such as histamine, caused by impaired detoxification by low activity of di-amino-oxidase, may play an additional role and could be considered in the proposed diet.

A recent study from Mexico investigated 56 patients with recurrent attacks of migraine (at least once a month) and 56 control subjects without migraine and measured their allergen-specific IgG against 108 food allergens by enzyme immunoassay (24). The authors reported that there was a statistically significant difference in the number of positive results for IgG food allergens between patients and controls and the elimination diet successfully controls the migraine without need of medication. As distinct from this study, we used a randomised, cross-over design with clear definition of diagnostic and follow-up criteria and study set-up. We used a baseline period and provocative diet periods to compare elimination diet period of the same individuals as their own controls instead of using other healthy volunteers.

Our data confirm the importance of determination of specific IgG antibodies against food antigens for prevention and cure of food-induced migraine attacks, leading to lower drug consumption, fewer adverse drug reactions and fewer days with migraine.

Conclusions

Diet restriction based on IgG antibodies might be an effective strategy in reducing the frequency of migraine attacks and could be implemented for therapy-resistant patient. However, because of the small sample size of this study, caution is required while translating these results into daily practice. Further research is also needed to determine the mechanism of IgG positive, food-induced migraine and its relation to other triggers.

Acknowledgements

Kadriye Alpay and Mustafa Ertaş contributed equally to the study. Mustafa Ertaş conducted the statistical analyses; he is a lecturer in biostatistics.

Appendix 1

Full list of 266 food allergens tested

Milk

-

Milk (cow)

Goat: milk and cheese

Milk products

-

Buttermilk

Cottage cheese

Yogurt

Whey

Curd cheese

Camembert

Edam cheese

Emmenthal cheese

Gouda cheese

Leerdamer cheese

Mozzarella

Parmesan

Ricotta

Roquefort

Processed cheese

Tilsit cheese

Sheep cheese

Food additives

-

Benzoic acid (E211)

Citric acid (E330)

Sorbic acid (E200)

Agar-Agar (E406)

Carrageen (E407)

Gelatine

Guar flour (E412)

Pectin (E440)

Traganth (E413)

Amarant (E123)

Azorubin (E122)

Quinoline yellow (E104)

Cochinella (E120)

Erytrosin (E127)

Yellow Orange FCF (E110)

Curcumin (E100)

Tartrazine (E102)

Glutamate (E621)

Aspergillus niger

Starch

Spelt

Barley

Gluten

Unripe spelt grain

Oat

Kamut

Rye

Wheat

Amaranth

Broad bean

Buckwheat

Millet

Potato

Chickpeas

Lentil

Maize, sweet corn

Quinoa

Rice

Soy bean

Tapioca, cassava

Infusions

-

Valerian

Nettle

Tea, green

Rose hip

Hibiscus leaves

Coffee

Chamomile

Lime blossoms

Rooibus tea

Tea, black

Hawthorn

Other additives

-

Aloe Vera

Rape-seed oil

Tannin

Eggs

Yellow chicken egg

Chicken egg white

Sugar products

-

Agave nectar

Maple syrup

Aspartame (E951)

Carob

Honey

Coconut

Malt

Cane sugar

Spices

-

Aniseed

Basil

Savory

Cayenne pepper

Chili

Candied lemon peel

Curry powder

Dill

Vervain

Hop

Ginger

Cardamom

Chervil

Garlic

Coriander

Caraway

Lavender

Lovage

Bay leaf

Marjoram

Horseradish

Nutmeg

Clove

Oregano

Paprika

Parsley

Parsley root

Peppermint

Allspice

Rosemary

Saffron

Sage

Chive

Pepper, black

Mustard seed

Thyme

Vanilla

Juniper berry

Pepper, white

Cinnamon

Lemon balm

Meat

-

Veal

Lamb

Beef

Pork

Duck

Goose

Chicken

Ostrich meat

Turkey hen

Quail

Rabbit

Deer

Hare

Roe deer

Wild boar

Seafood

-

Eel

Anchovy

Trout

Shark

Sole

Herring

Cod, codling

Carp

Salmon

Mackerel

Ocean perch

Sardine

Haddock

Plaice

Swordfish

Tuna fish

Zander

Oysters

Blue mussels

Squid

Shrimp, prawn

Lobster

Crayfish

Fruits

-

Pineapple

Apple

Apricot

Banana

Pear

Blueberry

Blackberry

Strawberry

Fig

Raspberry

Honeydew melon

Cherry

Kiwi

Lychee

Mandarin

Mango

Yellow plum

Nectarine

Orange

Grapefruit

Papaya

Peach

Plum

Cranberry

Quince

Sea buckthorn

Currant

Gooseberry

Grape

Watermelon

Lemon

Sugar melon

Chestnut

Date

Raisins

Avocado

Olive

Seeds and nuts

-

Cashew kernels

Peanut

Hazelnut

Coconut

Pumpkin seeds

Linseed

Almond

Poppy seeds

Brazil nut

Pine nut

Pistachio

Sesame

Sunflower seed

Walnut

Vegetables

-

Artichoke

Aubergine

Bamboo shoots

Cauliflower

Beans, yellow

Green bean

Broccoli

Chinese cabbage

Green pea

Fennel

Savoy cabbage

Cucumber

Carrots

Rutabaga

Pumpkin

Leek

Chard, beet greens

Green gram

Sweet pepper

Radish red

Radish black

Rhubarb

Brussels sprouts

Beetroot

Red cabbage

Shallot

Black salsify

Celeriac, knob celery

Asparagus

Spinach

Tomato

White cabbage

Kale, curled kale

Courgette

Onion

Salads

Watercress

Chicory

Iceberg lettuce

Endive

Butterhead lettuce

Head lettuce

Dandelion

Radicchio

Romaine/Cos lettuce

Rocket

Mushrooms

-

Oyster mushrooms

Meadow mushrooms

Bay boletus

Chanterelle

Shiitake

Cep (boletus)

Yeast

-

Yeast

Baking powder

References

- 1.Longoni M, Ferrarese C. Inflammation and excitotoxicity: role in migraine pathogenesis. Neurol Sci 2006; 27(Suppl 2): S107–S110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geppetti P, Capone JG, Trevisani M, Nicoletti P, Zagli G, Tola MR. CGRP and migraine; neurogenic inflammation revisited. J Headache Pain 2005; 6: 61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond S, Prager J, Freitag FG. Diet and headache Is there a link?. Postgrad Med J 1986; 79: 279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millichap JG, Yee MM. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol 2003; 28: 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peatfield RC, Glover V, Littlewood JT, Sandler M, Clifford Rose F. The prevalence of diet-induced migraine. Cephalalgia 1984; 4: 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peatfield RC. Relationships between food, wine, and beer-precipitated migrainous headaches. Headache 1995; 35: 355–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savi L, Rainero I, Valfre W, Gentile S, Lo Giudice R, Pinessi L. Food and headache attacks. A comparison of patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Panminerva Med 2002; 44: 27–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan TR. The role of food in the pathogenesis of migraine headache. Clin Rev Allergy 1994; 12: 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balyeat RM, Brittain FL. Allergic migraine: based on the study of fifty-five cases. Am J Med Sci 1930; 180: 212–221 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheldon JM, Randolph TG. Allergy in migraine-like headaches. Am J Med Sci 1935; 190: 232–236 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heymann H. Migraine and food allergy, a survey of 20 cases. S Afr Med J 1952; 26: 949–950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speer F. Allergy and migraine: a clinical study. Headache 1971; 11: 63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger J, Carter CM, Wilson J, Turner MW, Soothill JF. Is migraine food allergy? A double-blind controlled trial of oligoantigenic diet treatment. Lancet 1983; 2: 865–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monro J, Carini C, Brostoff J. Migraine is a food-allergic disease. Lancet 1984; 2: 719–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansfield LE, Vaughan TR, Waller SF, Haverly RW, Ting S. Food allergy and adult migraine: double-blind and mediator confirmation of an allergic etiology. Ann Allergy 1985; 55: 126–129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halpern GM, Scott JR. Non-IgE antibody mediated mechanisms in food allergy. Ann Allergy 1987; 58: 14–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aljada A, Mohanty P, Ghanim H, et al. Increase in intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB and decrease in inhibitor kappaB in mononuclear cells after a mixed meal: evidence for a proinflammatory effect. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 682–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilders-Truschnig M, Mangge H, Lieners C, Gruber H, Mayer C, Marz W. IgG antibodies against food antigens are correlated with inflammation and intima media thickness in obese juveniles. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2008; 116: 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2004; 53: 1459–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zar S, Mincher L, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Food-specific IgG4 antibody-guided exclusion diet improves symptoms and rectal compliance in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 800–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drisko J, Bischoff B, Hall M, McCallum R. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with a food elimination diet followed by food challenge and probiotics. J Am Coll Nutr 2006; 25: 514–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuo XL, Li YQ, Li WJ, et al. Alterations of food antigen-specific serum immunoglobulins G and E antibodies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37: 823–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rees T, Watson D. A prospective audit of food intolerance among migraine patients in primary care clinical practice. Headache Care 2005; 2: 11–14 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arroyave Hernandez CM, Echevarria Pinto M, Hernandez Montiel HL. Food allergy mediated by IgG antibodies associated with migraine in adults. Rev Alerg Mex 2007; 54: 162–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bic Z, Blix GG, Hopp HP, Leslie FM, Schell MJ. The influence of a low-fat diet on incidence and severity of migraine headaches. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 1999; 8: 623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bigal ME, Krymchantowski AV. Migraine triggered by sucralose – a case report. Headache 2006; 46: 515–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel RM, Sarma R, Grimsley E. Popular sweetner sucralose as a migraine trigger. Headache 2006; 46: 1303–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman LC, Lipton RB. Migraine MLT-down: an unusual presentation of migraine in patients with aspartame-triggered headaches. Headache 2001; 41: 899–901 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Eeden SK, Koepsell TD, Longstreth Jr WT, van Belle G, Daling JR, McKnight B. Aspartame ingestion and headaches: a randomized crossover trial. Neurology 1994; 44: 1787–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blau JN. Migraine triggers: practice and theory. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1992; 40: 367–372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tfelt-Hansen P, Block G, Dahlof C, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2000; 20: 765–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1): 9–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Obesity, migraine, and chronic migraine: possible mechanisms of interaction. Neurology 2007; 68: 1851–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology 2006; 66: 545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]