Abstract

The study design includes a systematic literature review. The objective of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery and to compare this with open microdiscectomy in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. Transforaminal endoscopic techniques for patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations have become increasingly popular. The literature has not yet been systematically reviewed. A comprehensive systematic literature search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was performed up to May 2008. Two reviewers independently checked all retrieved titles and abstracts and relevant full text articles for inclusion criteria. Included articles were assessed for quality and outcomes were extracted by the two reviewers independently. One randomized controlled trial, 7 non-randomized controlled trials and 31 observational studies were identified. Studies were heterogeneous regarding patient selection, indications, operation techniques, follow-up period and outcome measures and the methodological quality of these studies was poor. The eight trials did not find any statistically significant differences in leg pain reduction between the transforaminal endoscopic surgery group (89%) and the open microdiscectomy group (87%); overall improvement (84 vs. 78%), re-operation rate (6.8 vs. 4.7%) and complication rate (1.5 vs. 1%), respectively. In conclusion, current evidence on the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery is poor and does not provide valid information to either support or refute using this type of surgery in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. High-quality randomized controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes are direly needed to evaluate if transforaminal endoscopic surgery is more effective than open microdiscectomy.

Keywords: Lumbar disc herniation, Transforaminal, Endoscopic surgery, Minimally invasive surgery, Systematic review

Introduction

Surgery for lumbar disc herniation can be classified into two broad categories: open versus minimally invasive surgery and posterior versus posterolateral approaches. Mixter and Barr in 1934 were the first authors to treat lumbar disc herniation surgically by performing an open laminectomy and discectomy [41]. With the introduction of the microscope, Caspar and Yasargil refined the original laminectomy into open microdiscectomy [4, 63]. Laminectomy and microdiscectomy are open procedures using a posterior approach. Currently, open microdiscectomy is the most widespread procedure for surgical decompression of radiculopathy caused by lumbar disc herniation, but minimally invasive surgery has gained a growing interest. The concept of minimally invasive surgery for lumbar disc herniations is to provide surgical options that optimally address the disc pathology without producing the iatrogenic morbidity associated with the open surgical procedures. In the last decades, endoscopic techniques have been developed to perform discectomy under direct view and local anaesthesia.

Kambin and Gellmann in 1973 [22] in the United States and Hijikata in Japan in 1975 [12], independently performed a non-visualised, percutaneous central nucleotomy for the resection and evacuation of nuclear tissue via a posterolateral approach. In 1983, Forst and Housman reported the direct visualization of the intervertebral disc space with a modified arthroscope [9]. Kambin published the first intraoperative discoscopic view of a herniated nucleus pulposus in 1988 [21]. In 1989 and 1991 Schreiber et al. described ‘percutaneous discoscopy’, a biportal endoscopic posterolateral technique with modified instruments for direct view [52, 55]. In 1992, Mayer introduced percutaneous endoscopic laser discectomy combining forceps and laser [40]. With the further improvement of scopes (e.g. variable angled lenses and working channel for different instruments), the procedure became more refined. The removal of sequestered non-migrated fragments became possible using a biportal approach [25]. The concept of posterolateral endoscopic lumbar nerve decompression changed from indirect central nucleotomy (inside out, in which fragments are extracted through an annular fenestration outside the spinal canal) to transforaminal direct extraction of the non-contained and sequestered disc fragments from inside the spinal canal. In this article, the technique of direct nucleotomy is described as intradiscal and the technique directly in the spinal canal is described as intracanal technique; both are transforaminal approaches (Fig. 1).

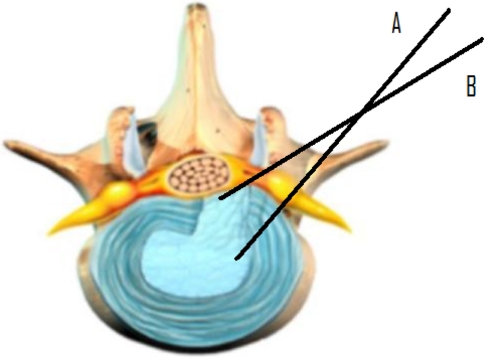

Fig. 1.

Different posterolateral approaches to the lumbar disc. a The intradiscal technique, b the intracanal technique

The indications for transforaminal endoscopic treatment are the same as classical discectomy procedures [6, 24, 38]. To reach the posterior part of the epidural space, the superior articular process of the facet joint is usually the obstacle. Yeung and Knight used a holmium-YAG (yttrium-aluminium-garnet)—laser for ablation of bony and soft tissue for decompression, enhanced access and to improve intracanal visualisation [30, 64]. Yeung developed the commercially available Yeung Endoscopic Spine System (YESS) in 1997 [65] and Hoogland in 1994 developed the Thomas Hoogland Endoscopic Spine System (THESSYS). With this latter system, it is possible to enlarge the intervertebral foramen near the facet joint with special reamers to reach intracanal extruded and sequestered disc fragments and decompress foraminal stenosis [16].

Recently, also another minimally invasive technique, microendoscopic discectomy (MED), has been developed. In MED, a microscope is used and the spine is approached from a posterior direction and not transforaminal. Therefore, this technique is not considered in the current systematic review.

Endoscopic surgery for lumbar disc herniations has been available for more than 30 years, but at present a systematic review of all relevant studies on the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations is lacking.

Methods

Objective

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. The main research questions were

- What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery?

- What is the effectiveness of the older intradiscal transforaminal technique and the more recently developed extracanal transforaminal technique?

- What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery for the different types of herniations (mere lateral herniations versus central herniations versus all types of lumbar disc herniations)?

What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery when compared with open microdiscectomy?

For this systematic review, we used the method guidelines for systematic reviews as recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group [61]. Below the search strategy, selection of the studies, data extraction, methodological quality assessment and data analysis are described in more detail. All these steps were performed by two independent reviewers and during consensus meetings potential disagreements between the two reviewers regarding these issues were discussed. If they were not resolved, a third reviewer was consulted.

Search strategy

An experienced librarian performed a comprehensive systematic literature search. The MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were searched for relevant studies from 1973 to May 2008. The search strategy consisted of a combination of keywords concerning the technical procedure and keywords regarding the anatomical features and pathology (Table 1). We conducted two reviews, one on lumbar disc herniation and one on spinal stenosis, and combined the search strategy for these two reviews for efficiency reasons. These keywords were used as MESH headings and free text words. The full search strategy is available upon request.

Table 1.

Selection of terms used in our search strategy

| Technical procedure | Anatomical features/disorder |

|---|---|

| Endoscopy | Spine |

| Arthroscopy | Back |

| Video-assisted surgery | Back pain |

| Surgical procedures, minimally invasive | Spinal diseases |

| Microsurgery | Disc displacement |

| Transforaminal | Intervertebral disc displacement |

| Discectomy | Spinal cord compression |

| Percutaneous | Sciatica |

| Foraminotomy, foraminoplasty discoscopy | Radiculopathy |

Selection of studies

The search was limited to English, German and Dutch studies, because these are the languages that the review authors are able to read and understand. Two review authors independently examined all titles and abstracts that met our search terms and reviewed full publications, when necessary. In addition, the reference sections of all primary studies were inspected for additional references. Studies were included that describe transforaminal endoscopic surgery for adult patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. As we expected only a limited number of randomized controlled trials in this field, we also included observational studies (non-randomized controlled clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies and retrospective patient series). To be included, studies had to report on more than 15 cases, with a follow-up period of more than 6 weeks.

Data extraction

Two review authors independently extracted relevant data from the included studies regarding design, population (e.g. age, gender, duration of complaints before surgery, etc), type of surgery, type of control intervention, follow-up period and outcomes. Primary outcomes that were considered relevant are pain intensity (e.g. visual analogue scale or numerical rating scale), functional status (e.g. Roland Morris Disability Scale, Oswestry Scale), global perceived effect (e.g. McNab score, percentage patients improved), vocational outcomes (e.g. percentage return to work, number of days of sick leave), and other outcomes (recurrences, complication, re-operation and patient satisfaction). We contacted primary authors where necessary for clarification of overlap of data in different articles.

Methodological quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. Controlled trials were assessed using a criteria list recommended by the Cochrane Back review group as listed in Table 2 [61]. If studies met at least 6 out of the 11 criteria, the study was considered to have a low risk of bias (RoB). If only 5 or less of the criteria were met, the study was labelled as high RoB Non-controlled studies were assessed using a modified 5-point assessment score as listed in Table 3. Disagreements were resolved in a consensus meeting and a third review author was consulted when necessary.

Table 2.

Criteria list for quality assessment of controlled studies

| A | Was the method of randomization adequate? | Y | N | ? |

| B | Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Y | N | ? |

| C | Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | Y | N | ? |

| D | Was the patient blinded to the intervention? | Y | N | ? |

| E | Was the care provider blinded to the intervention | Y | N | ? |

| F | Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? | Y | N | ? |

| G | Were co-interventions avoided or similar? | Y | N | ? |

| H | Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? | Y | N | ? |

| I | Was the drop out rate described and acceptable? | Y | N | ? |

| J | Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all groups similar? | Y | N | ? |

| K | Did the analysis include an intention to treat analysis? | Y | N | ? |

? score unclear

A: A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods are computer generated random number table and use of sealed opaque envelopes. Methods of allocation using date of birth, date of admission, hospital numbers or alternation should not be regarded as appropriate

B: Assignment generated by an independent person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the patients. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about eligibility of the patient

C: In order to receive a ‘yes’, groups have to be similar at baseline regarding demographic factors, duration and severity of complaints, percentage of patients with neurological symptoms and value of main outcome measure(s)

D: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a ‘yes

E: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a ‘yes’

F: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a ‘yes’

G: Co-interventions should either be avoided in the trial design or similar between the index and control groups

H: The reviewer determines if the compliance to the interventions is acceptable, based on the reported intensity, duration, number and frequency of sessions for both the index intervention and control intervention(s)

I: The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given. If the percentage of withdrawals and drop outs does not exceed 20% for short-term follow-up and 30% for long-term follow-up and does not lead to substantial bias a ‘yes’ is scored. (N.B. these percentages are arbitrary, not supported by literature)

J: The timing of outcome assessment should be identical for all intervention groups and for all important outcome assessments

K: All randomized patients are reported/analysed in the group they were allocated to by randomization for the most important moments of effect measurement (minus missing values) irrespective of non-compliance and co-interventions

Table 3.

Criteria list for quality assessment of non-controlled studies

| A | Patient selection/inclusion adequately described? | Y | N | ? |

| B | Drop out rate described? | Y | N | ? |

| C | Independent assessor? | Y | N | ? |

| D | Co-interventions described? | Y | N | ? |

| E | Was the timing of the outcome assessment similar? | Y | N | ? |

? score unclear

A: All the basic elements of the study population are adequately described; i.e. demography, type and level of disorder, physical and radiological inclusion and exclusion criteria, pre-operative treatment and duration of disorder

B: Are the patients of whom no outcome was obtained, described in quantity and reason for drop out

C: The data were assessed by an independent assessor

D: All co-interventions in the population during and after the operation are described

E: The timing of outcome assessment should be more or less identical for all intervention groups and for all important outcome assessments

Data analysis

To assess the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery and to compare it to open microdiscectomy, the results of outcome measures were extracted from the original studies. The outcome data of some studies were recalculated, because the authors of the original papers did not handle drop outs, lost to follow-up and/or failed operations adequately. If a study reported several follow-up intervals, the outcome of the longest follow-up moment was used.

Because only one randomized trial was identified and the controlled trials were heterogeneous regarding study populations, endoscopic techniques, outcome measures, measurement instruments and follow-up moments, statistical pooling was not performed. The median and range (min–max) of the results of the individual studies for each outcome measure are presented.

Results

Search and selection

Two thousand five hundred and thirteen references were identified in MEDLINE and EMBASE that were potentially relevant for the reviews on lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis. After checking the titles and abstracts, a total of 123 full text articles were retrieved that were potentially eligible for this review on lumbar disc herniation. Reviewing the reference lists of these articles resulted in an additional 17 studies. Some patient cohorts were described in more than one article. In these cases, all articles were used for the quality assessment of the study, but outcome data reporting the longest follow-up was used. After scrutinising all full text papers, 39 studies reported in 45 articles were included in this review. Sixteen studies (41%) had a mean follow-up of more than 2 years. The characteristics and outcomes of the included studies are presented in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Table 4.

Prospective controlled studies

| Study/author, methodology | Main inclusion criteria, main exclusion criteria | Type/level LDH | Interventions/technique/instrumentation | Follow-up: duration and outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hermantin et al. [11], randomized n = 60 | Inclusion criteria | Type: intracanal LDH | Index: arthroscopic microdiscectomy | Follow-up I: mean 31 months (range 19–42), 0% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Pure intradiscal technique Kambin technique biportal: n = 2 | C: mean 32 months (range 21–42), 0% lost to follow-up | ||

| Post-tension sign | n = 30 ♀8 ♂22, mean 39 years, range 15–66 | Pain (VAS) I: pre-op. 6.6, follow-up 1.9, difference 4.7 = 71% | |||

| Neurological deficit | Control: open Laminotomie, n = 30 ♀13 ♂17, mean 40 years, range 18–67 | C: pre-op. 6.8, follow-up 1.2, difference 5.6 = 82% | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Return to work (mean): I: 27, C: 49 days | ||||

| Sequestration | GPE (unclear instrument) I: 97%, C: 93% excellent + good | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | PS (very satisfied) I: 73%, C: 67% | ||||

| Central or lateral stenosis | Complications I: 6.7%, C: 0% | ||||

| Re-operations I: 6.7%, C: 3.3% | |||||

| Hoogland et al. [16], not adequately randomized (birth date) n = 280 | Inclusion criteria | Type: all LDH | Index: transforaminal endoscopic discectomy | Follow-up I: 24 months, 16% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Intradiscal and intracanal technique, Thessys instrumentation, n = 142 ♀50 ♂92, mean 41 years, range 18–60 | C: 24 months, 16% lost to follow-up | ||

| Post-tension sign | Control: transforaminal endoscopic discectomy combined with injection of low-dose (1,000 U) chymopapain. n = 138 ♀44 ♂94, mean 40.3 years, range 18–60 | Pain leg (VAS) I: pre-op. 8.0, follow-up 2.0, difference 6.0 = 75% | |||

| Neurological deficit | C: pre-op. 8.2, follow-up 1.9, difference 6.3 = 77% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Pain back (VAS) I: pre-op. 8.2, follow-up 2.6, difference 5.6 = 68% | ||||

| Obesity | C: pre-op. 8.2, follow-up 2.8, difference 5.4 = 66% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | GPE (MacNab) I: 16% excellent, 33.8% good, 0.9% poor | ||||

| C: 63% excellent, 27% good, 0.9% poor NS | |||||

| PS I: 85%, C: 93% S | |||||

| Recurrence I: 7.4%, C: 4.0% | |||||

| Complications I: 2.1%, C: 2.2% NS | |||||

| Re-operations I: 6.1%, C: 1.6% | |||||

| Krappel et al. [31], not adequately randomized (alternating) n = 40 | Inclusion criteria | Type: not specified | Index: endoscopic transforaminal nucleotomy | Follow-up I: range 24–36 months, 5% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L4–S1 | Pure intradiscal technique, Mathews technique, Sofamor–-Danek endoscope, n = 20 ♀? ♂?, mean 41 years, range 36–54 | C: range 24–36 months, 0% lost to follow-up | ||

| Post-tension sign | Control: Open nucleotomy, n = 20 ♀? ♂?, mean 39 years, range 25–43 | GPE (MacNab) I: 16% excellent, 68% good, 0% poor | |||

| Neurological deficit | C: 15% excellent, 60% good, 0% poor NS | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Return to work I: 100%, C 100% | ||||

| Sequestration | Recurrence I: 5%, C 0% | ||||

| High iliac crest | Complications I: 0%, C 0% | ||||

| Re-operations I: 5%, C 0% | |||||

| Lee et al. [34], not adequately randomized, (preference of surgeon) n = 300 | Inclusion criteria | Type: not specified | Index: percutaneous endoscopic laser discectomy (PELD), n = 100 ♀35 ♂65 | Follow-up 12 months, 0% lost to follow-up | Authors included n = 3 patients in satisfactory group after re-operation. These were labelled as ‘adverse effects’ and ‘re-operations’ in this review |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L3–S1 | Pure intradiscal technique, Kambin technique | GPE (modified MacNab) I: 29%, C1: 20%, C2: 18% excellent | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Control 1: chemonucleolysis, n = 100 ♀24 ♂76 | I: 39%,C1: 35%, C2: 30% good | |||

| Sequestration | Control 2: automated percutaneous discectomy, n = 100 ♀28 ♂72 | I: 9%, C1: 18%, C2: 20% poor | |||

| Return to work (6 weeks) I: 81%, C1: 67%, C2: 66% | |||||

| Complications I: 4%, C1: 10%, C2: 3% | |||||

| Re-operations I: 9%, C1: 18%, C2: 20% | |||||

| Mayer and Brock [39], randomization not specified n = 40 | Inclusion criteria | Type: not specified | Index: percutaneous endoscopic discectomy | Follow-up 24 months, 0% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L2–L5 | Pure intradiscal technique, modified Hjikata instrumentation, n = 20 ♀8 ♂12, mean 40 years, range 12–55 | GPE (S/S-score) I: 70% satisfactory, 0% poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Control: open microdiscectomy, n = 20 ♀6 ♂14, mean 42 years, range 19–63 | C: 65% satisfactory, 15% poor | |||

| Neurological deficit | Patient satisfaction I: 55%, C: 55% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Recurrence I: 5%, C: 0% | ||||

| Sequestration | Complications I: 0%, C: 5% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | Re-operations I: 15%, C: 5% | ||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Ruetten et al. [47], not adequately randomized (alternating by independent person) n = 200 | Inclusion criteria | Type: all LDH | Index: endoscopic transforaminal and interlaminar lumbar discectomy | Follow-up I: 24 months, 8% lost to follow-up | Authors excluded n = 6 from analyses due to revision surgery. These were taken into account in this review, n = 41 were operated via a transforaminal endoscopic technique, n = 59 patients were operative via an interlaminar endoscopic technique |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L1–S1 | Intracanal technique, YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation, n = 100 | C: 24 months, 8% lost to follow-up | ||

| Neurological deficit | Control: open microdiscectomy, n = 100, mean 43 years, range 20–68 | Pain leg (VAS) I: pre-op.75, follow-up 8, difference 67 = 89% | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Overall, n = 200 ♀116 ♂84, mean 43 years, range 20−68 | C: pre-op. 71, follow-up 9, difference 62 = 87% | |||

| Not specified | Pain back (VAS) I: pre-op. 19, follow-up 11, difference 8 = 42% | ||||

| C: pre-op. 15, follow-up 18, difference −3 = −8.3% | |||||

| Functional status: (ODI) I: pre-op. 75, follow-up 20, difference 55 = 73% | |||||

| C: pre-op. 73, follow-up 24, difference 49 = 67% | |||||

| Patient satisfaction I: 97%, C: 88% | |||||

| Return to work (mean) I: 25 days | |||||

| C: 49 days S | |||||

| Recurrence I: 6.6% C: 5.7% NS | |||||

| Complications I: 3%, C: 12% S | |||||

| Re-operations I: 6.8% C: 11.5 |

Intervention as quoted in original article. Post-tension signs denotes positive tension signs (straight leg raising test or contralateral straight leg raising test)

Outcomes: S statistically significant, NS not statistically significant, PS patient satisfaction, MacNab MacNab score as described by MacNab [39]. The sum of ‘excellent’ and ‘good’ outcomes are labelled ‘satisfactory’, GPE global perceived effect, S/S-score Suezawa and Schreiber score [40], ODI Oswestry disability index [38]

Table 5.

Retrospective controlled studies

| Study, methodology | Main inclusion criteria, main exclusion criteria | Type/level LDH | Interventions/technique/instrumentation | Follow-up: duration and outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. [26], all patients that underwent the procedures in a certain period | Inclusion criteria | Type: central, paramedian and foraminal LDH | Index: percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy (PTED) | Follow-up: mean 23.6 months (range 18–36), I: 2.5%, C: 3.5% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L1–S1 | Intradiscal and intracanal technique, YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation, n = 295 ♀107 ♂188, mean 35 years, range 13–83 | GPE (MacNab) I: 47% excellent, 37% good, 5.4% poor | ||

| C: 48% excellent, 37% good, 6.6% poor NS | |||||

| Post-tension sign | Control: open microdiscectomy, n = 607 ♀215 ♂392, mean 44 years, range 17–80 | Recurrence I: 6.4% C: 6.8% NS | |||

| Neurological deficit | Complications I: 3.1% C: 2.0% NS | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations I: 9.5% C: 6.3% NS | ||||

| Extraforaminal LDH | |||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Spinal stenosis | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Spondylolisthesis | |||||

| Lee et al. [32], randomly selected patients with follow-up > 3 years in both groups | Inclusion criteria | Type: not specified | Index: percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) | Follow-up I: mean 38 months (range 32–45), 0% lost to follow-up | Primary outcome of the study was a radiologic evaluation |

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L4–S1 | Pure intradiscal technique, instrumentation not specified, n = 30 ♀8 ♂22, mean 40 years, range 22–67 | C: 35–42 (36) months, 0% non-responders | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Control: open microdiscectomy, n = 30 ♀8 ♂22, mean 40 years, range 20–64 | GPE (MacNab) I: 80% excellent, 17% good, 3.3% poor | |||

| Stenosis | C: 78% excellent, 17% good, 0% poor | ||||

| Segmental instability | Complications I: 0%, C: 0% | ||||

| Re-operations I: 3.3%, C: 0% |

Intervention as quoted in original article. Post-tension signs denotes positive tension signs (straight leg raising test or contralateral straight leg raising test)

Table 6.

Prospective cohort studies

| Study | Main inclusion criteria, main exclusion criteria | Number of participants type/level LDH | Interventions/technique/instrumentation | Follow-up: duration and outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoogland et al. [17] | Inclusion criteria | n = 262 ♀76 ♂186, mean 46 years, range 18–80 | Endoscopic transforaminal discectomy (ETD) | Follow-up: 24 months, 9% lost to follow-up | Authors included only patients with recurrent LDH, more than 6 months after open microdiscectomy or endoscopic surgery |

| Previous surgery (same level) | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 8.5, follow-up 2.6, differences 5.9 = 69% | ||

| Recurrent disc herniation | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Thessys instrumentation | Pain back (VAS): pre-op. 8.6, follow-up 2.9, difference 5.7 = 66% | ||

| Radiculopathy | GPE (MacNab): 31% excellent, 50% good, 2.5% poor | ||||

| Post-tension sign | Patient satisfaction: 51% excellent, 35% good, 5% poor | ||||

| Neurological deficit | Recurrence: 6.3% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Complications: 1.1% | ||||

| Not specified | Re-operations: 7% | ||||

|

Hoogland and Schenkenbach [15] Schenkenbach and Hoogland [51] |

Inclusion criteria | n = 130 ♀43 ♂87, mean 39 years | Endoscopic transforaminal discectomy (ETD) | Follow-up: 12 months, 5.1% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | Pain leg (VAS): difference 5.9 | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Thessys instrumentation | Pain back (VAS): difference 5.4 | ||

| Neurological deficit | GPE (MacNab): 56% excellent, 27% good, 6% poor | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Return to work (6 weeks): 70% | ||||

| Not specified | Complications: 1.5% | ||||

| Re-operations: 4.6% | |||||

| Kafadar et al. [20] | Inclusion criteria | n = 42 ♀2 ♂40, range 18–74 years | Percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal discectomy (PETD) | Follow-up: mean 15 months (range 6–24) (SD 4), 0% lost to follow-up | Authors excluded n = 8 from analyses due to stopped procedures. These were taken into account in this review |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (S/S-score): 14% excellent, 36% good 36% poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L4–L5 | Karl Storz instrumentation | Recurrence: 0% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 45% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 17% | ||||

| Previous surgery(same level) | |||||

| Spinal stenosis | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Calcified LDH | |||||

| Kambin [23]; Kambin | Inclusion criteria | n = 175 ♀76 ♂99 | Arthroscopic microdiscectomy and selective fragmentectomy | Follow-up: mean 48 months (range 24–78), 3.4% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (Modified Presby, St Luke score): 77% excellent, 11% good, 12% failed | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L2−S1 | Kambin technique | Return to work (3 weeks): 95% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Biportal n = 59 | Complications: 5.3% | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 7.7% | ||||

| Large extraligamental LDH | |||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Degenerative disc | |||||

| Knight et al. [27]; Knight et al. [29] | Inclusion criteria | n = 250 ♀? ♂?, mean 48 years, range 21–86 | Endoscopic laser foraminoplasty (ELF) | Follow-up: mean 30 months (range 24–48) (SD 5.87), 3.2% lost to follow-up | Authors included also degenerative and lateral stenosis in this study |

| Prior disc surgery n = 75 | Type: All LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | Pain (VAS > 50% improvement): 56% | ||

| Back pain | Level: single and multiple level, L2–S1 | Richard Wolf instrumentation | Functional status (ODI): 60% improved ≥ 50% | ||

| Leg pain | Complications: 0.8% | ||||

| Radiculopathy | Re-operations: 5.2% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | |||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Painless motor deficit | |||||

| Lee et al. [33] | Inclusion criteria | n = 116 ♀43 ♂73, mean 36 years, range 18–65 | Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) | Follow-up: mean 14.5 months (range 9–20), 0% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 7.5, follow-up 2.6, difference 4.9 = 65% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: single level, L2–S1 | YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | GPE (Modified MacNab): 45% excellent, 47% good, 6.0% poor | ||

| Non-contained or sequestered LDH | Return to work: average 14 days, range 1–48 days | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Recurrence: 0% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | Complications: 0% | ||||

| Central or lateral stenosis | Re-operations: 0% | ||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Morgenstern et al. [42] | Inclusion criteria | n = 144 ♀48 ♂96, mean 46 years, range 18–76 | Endoscopic spine surgery | Follow-up: mean 24 months (range 3–48), 0% lost to follow-up | Primary outcome of this study was to compare normal versus intensive physical therapy post operative revalidation |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | GPE (MacNab): 83% excellent and good, 3% poor | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: multiple level n = 60, L1–S1 | YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | Complications: 9% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 5.6% | ||||

| Sequestration | |||||

| Ramsbacher et al. [45] | Inclusion criteria | n = 39 ♀21 ♂18, mean 50 years | Transforaminal endoscopic sequestrectomy (TES) | Follow-up: 6 weeks, 0% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intracanal technique | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 6.7, follow-up 0.8, difference 5.9 = 88% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: single level, L3–S1 | Sofamor–Danek endoscope | Pain back (VAS): pre-op. 5.1, follow-up 1.3, difference 3.8 = 74% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | PS: 77% (very satisfied + satisfied) | ||||

| Far migrated sequesters | Complications: 5.1% | ||||

| Central or lateral stenosis | Re-operations: 10% | ||||

| High iliac crest | |||||

| Ruetten et al. [46] | Inclusion criteria | n = 517 ♀277 ♂240, mean 38 years, range 16–78 | Extreme-lateral transforaminal approach | Follow-up: 12 months, 10% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intracanal technique, Richard Wolf instrumentation, n = 27 bilateral | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 7.1, follow-up 0.8, difference 6.3 = 89% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: multiple level n = 46, L1–L5 | Pain back (VAS): pre-op. 1.8, follow-up 1.6, difference 0.2 = 13% | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Functional status (ODI): pre-op. 78, follow-up 20, difference 58 = 74% | ||||

| Far cranial/caudal migrated sequester | Recurrence: 6.9% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | Complications: 0% | ||||

| Spinal stenosis | Re-operations: 6.9% | ||||

| Sasani et al. [48] | Inclusion criteria | n = 66 ♀36 ♂30, median 52 years, range 35–73 | Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy (PED) | Follow-up: 12 months, 0% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: foraminal + extraforaminal LDH | Pure intradiscal technique Karl Storz instrumentation | Pain (VAS): pre-op. 8.2, follow-up 1.2, difference 7.0 = 85% | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L2–L5 | Functional status (ODI): pre-op. 78, follow-up 8, difference 70 = 90% | |||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 6.1% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 7.6% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Schubert and Hoogland [54] | Inclusion criteria | n = 558 ♀179 ♂379, mean 44 years, range 18–65 | Transforaminal nucleotomy with foraminoplasty | Follow-up: 12 months, 8.7% lost to follow-up | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intracanal technique, Thessys instrumentation | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 8.4, follow-up 1.0, difference 7.4 = 88% | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Pain back (VAS): pre-op. 8.6, follow-up 1.4, difference 7.2 = 84% | |||

| Neurological deficit | GPE (MacNab): 51% excellent, 43% good, 0.3% poor | ||||

| Sequestration | Recurrence: 3.6% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Complications: 0.7% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | Re-operations: 3.6% | ||||

| Suess et al. [57] | Inclusion criteria | n = 25 ♀11 ♂14, mean 48 years, range 26–72 | Percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic sequestrectomy (PTFES) | Follow-up: 6 weeks, 0% lost to follow-up | All patients operated under general anaesthesia and EMG monitoring |

| Radiculopathy | Type: foraminal + extraforaminal LDH | Pure intradiscal technique, instrumentation not specified | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 6.7, follow-up 0.8, difference 5.9 = 88% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: single level, L2–L5 | Pain back (VAS): pre-op. 5.1, follow-up 1.3, difference 3.8 = 75% | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Complications: 4% | ||||

| Cauda syndrome | Re-operations: 8% | ||||

| Spinal stenosis |

Intervention as quoted in original article. Post-tension signs denotes positive tension signs (straight leg raising test or contralateral straight leg raising test)

Outcomes: S statistically significant, NS not statistically significant, PS patient satisfaction, MacNab MacNab score as described by MacNab [39]. The sum of ‘excellent’ and ‘good’ outcomes are labelled ‘satisfactory’, GPE global perceived effect, S/S-score Suezawa and Schreiber score [40], Presby. St Luke score Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke score [23], ODI Oswestry disability index [38]

Table 7.

Retrospective cohort studies

| Study | Main inclusion criteria, main exclusion criteria | Type /level LDH | Interventions/technique/instrumentation | Follow-up: duration and outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al. [3] | Inclusion criteria | n = 43 ♀11 ♂32, mean 46 years, range 22–72 | Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) | Follow-up: range 24–39 months, 0% non-responders | Authors included only patients with recurrent LDH, more than 6 months after open microdiscectomy |

| Prior disc surgery | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique, instrumentation not specified | Pain (VAS): pre-op. 8.7, follow-up 2.6, difference 6.1 = 70% | ||

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L3–S1 | GPE (MacNab): 28% excellent, 53% good, 4.7% poor | |||

| Post-tension sign | Complications: 4.6% | ||||

| Neurological deficit | Re-operations: 2.3% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Spondylolisthesis | |||||

| Calcified fragments | |||||

| Chiu [5] | Inclusion criteria | n = 2,000 ♀990 ♂1010, mean 44 years, range 24–92 | Transforaminal microdecompressive endoscopic assisted discectomy (TF-MEAD) | Follow-up: mean 42 months (range 6–72), 0% non-responders | Authors included also patients with stenosis and degenerative disc disease |

| Virgin and prior disc surgery | Type: not specified | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | GPE (unclear instrument): 94% excellent or good, 3% poor | ||

| Pain in back | Level: single and multiple level | Karl Storz instrumentation | Complications: 1% | ||

| Radiculopathy | Re-operations: not specified | ||||

| Neurological deficit | |||||

| Exclusion criteria | |||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Painless motor deficit | |||||

| Choi et al. [6] | Inclusion criteria | n = 41, ♀23 ♂18, mean 59 years, range 32–74 | Extraforaminal targeted fragmentectomy | Follow-up: mean 34 months (range 20–58), 4.9% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: extraforaminal LDH | Pure intradiscal technique, YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | Pain leg (VAS): pre-op. 8.6, follow-up 1.9, difference 6.7 = 78% | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level, L4–S1 | Return to work: mean 6 weeks (range 4–24) | |||

| Neurological deficit | Functional status (ODI): pre-op. 66.3, follow-up 11.5, difference 54.8 = 83% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | PS: 92% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | Recurrence: 5.1% | ||||

| Central or lateral stenosis | Complications: 5.1% | ||||

| Segmental instability | Re-operations: 7.7% | ||||

| Calcified disc | |||||

| Ditsworth [7] | Inclusion criteria | n = 110 ♀40 ♂70, median 55 years, range 20 to > 60 | Endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy | Follow-up: range 24–48 months, 0% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | GPE (MacNab): 91% excellent or good, 4.5% poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: single level | Flexible endoscope | Recurrence: 0% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 0.9% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 4.5% | ||||

| Spinal stenosis | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Eustacchio [8] | Inclusion criteria | n = 122 ♀36 ♂86, median 55 years, range 18–89 | Endoscopic percutaneous transforaminal treatment | Follow-up: mean 35 months (range 15–53), 0% non-responders | Authors excluded n = 10 from analyses due to stopped procedures. These were taken into account in this review |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique instrumentation not specified | GPE (MacNab): 45% excellent, 27% good, 27% poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: multiple level n = 4, L2–S1 | Functional status (PROLO): 71.9% excellent or good | |||

| Neurological deficit | Return to work: 94% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Recurrence: 12% | ||||

| Cauda syndrome | Complications: 9% | ||||

| Re-operations: 27% | |||||

| Haag [10] | Inclusion criteria | n = 101 | Transforaminal endoscopic microdiscectomy | Follow-up: mean 28 months (range 15–26), 9% non-responders | Authors excluded n = 3 from analyses due to technical problems during procedures. These were taken into account in this review |

| Radiculopathy | Type: all LDH | Pure intradiscal technique | PS: good: 66%, satisfied: 9%, poor: 25% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: single level, L2–S1 | Sofamor–Danek instrumentation | Complications: 7.6% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 17% | ||||

| Discus narrowing | |||||

| Calcified disc | |||||

| Hochschuler [13] | Inclusion criteria | n = 18 ♀5 ♂13, mean 31 years, range 18–55 | Arthroscopic microdiscectomy (AMD) | Follow-up: mean 9 months (range 4–13), 0% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique | Re-operations: 11% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: L3−S1 | Kambin technique | |||

| Previous operation (same level) | |||||

| Sequestration | |||||

| High iliac crest | |||||

| Hoogland [14] | Inclusion criteria | n = 246 | Transforaminal endoscopic discectomy with foraminoplasty | Follow-up: 24 months, 0% non-responders | Authors included also patients with foraminal stenosis |

| Not specified | Type: not specified | Intracanal technique, Thessys instrumentation | GPE (MacNab): 86% excellent or good, 7.7% poor | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: not specified | Complications: 1.2% | |||

| Not specified | Re-operations (1st year): 3.5% | ||||

| Iprenburg [18] | Inclusion criteria | n = 149 ♀62 ♂87, mean 43 years, range 17–82 | Transforaminal endoscopic surgery | Follow-up: not specified, 29% non-responders | |

| Not specified | Type: all LDH | Intracanal technique, Thessys instrumentation | Pain (VAS): not specified | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: single level, L3–S1 | Functional status (ODI): not specified | |||

| Central stenosis | Recurrence: 6% | ||||

| Complications: not specified | |||||

| Re-operations: not specified | |||||

| Jang et al. [19] | Inclusion criteria | n = 35 ♀20 ♂15, mean 61 years, range 22–84 | Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy (TPED) | Follow-up: mean 18 months (range 10–35), 0% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: foraminal and extraforaminal LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique, instrumentation not specified | Pain (VAS): pre-op. 8.6, follow-up 3.2, difference 5.4 = 63% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: single level, L2–S1 | GPE (MacNab): 86% excellent or good, 8.6% poor | |||

| Previous surgery (same level) segmental instability | Recurrence: 0% | ||||

| Spinal stenosis | Complications: 17% | ||||

| Listhesis | Re-operations: 8.6% | ||||

| Lew et al. [35] | Inclusion criteria | n = 47 ♀12 ♂35, mean 51 years, range 30–70 | Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy | Follow-up: mean 18 months (range 4–51), 0% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: foraminal and extraforaminal LDH | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (MacNab): 85% excellent or good, 11% poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: L1–L5 | Surgical dynamics instrumentation | Return to work: 89% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 0% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 11% | ||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Mayer and Brock [39] | Inclusion criteria | n = 30 ♀11 ♂19 | Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) | Follow-up: range 6–18 months, 0% non-responders | Twenty of the patients were described in a prospective study [41]. In this review reoperations were labelled as moderate or poor outcome on GPE |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique, instrumentation not specified | GPE (S/S-score): 67% excellent or good, 33% moderate or poor | ||

| Post-tension sign | Level: multiple level n = 1, L2–L5 | Return to work: 7.1 ± 4.2 weeks, 90% (6 months) | |||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 3.3% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 3.3% | ||||

| Sequestration | |||||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Spinal stenosis | |||||

| Listhesis | |||||

| Savitz [49, 50] | Inclusion criteria | n = 300 ♀132 ♂168, range 16–81 years | Percutaneous lumbar discectomy with endoscope | Follow-up: 6 months, 0% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | |||||

| Post tension sign | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique, Kambin technique | Return to work (6 months): 67% | ||

| Neurological deficit | |||||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: multiple level n = 40, L2–S1 | Complications: 5.3% | |||

| Previous surgery (same level) | |||||

| Sequestration | Re-operations: 1.3% | ||||

| Obesity | |||||

| Schreiber and Suezawa [53]; Suezawa and Schreiber [58]; Leu and Schreiber [36]; Schreiber and Leu [52] | Inclusion criteria | n = 174 ♀68 ♂106, mean 39 years, range 16–81 | Percutaneous nucleotomy with discoscopy | Follow-up: mean 28 months, 0% non-responders | Authors included also patients with degenerative disc disease, only the scores from LDH are quoted in this review |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (S/S-score): 85% excellent or good | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: multiple level n = 25 | Modified Hijikata instrumentation biportal | Complications: 10% | ||

| Sequestration | Re-operations: 21% | ||||

| Shim et al. [56] | Inclusion criteria | n = 71 ♀39 ♂32, mean 45 years, range 21–74 | Transforaminal endoscopic surgery | Follow-up: mean 6 months (range 3–9), 0% non-responders | n = 14 patients with L5−S1 level LDH are operated via a interlaminar approach |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (MacNab): 33% excellent, 45% good, 6.5% poor | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: single level, T12–S1 | YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | Complications: 2.8% | ||

| Not specified | Re-operations: 7.0% | ||||

| Tsou and Yeung [59] | Inclusion criteria | n = 219 ♀83 ♂136, mean 42 years range 17–71 | Transforaminal endoscopic decompression | Follow-up: mean 20 months (range 12–108), 11.9% non-responders | Possible patient overlap with other study [65] |

| Radiculopathy | Type: central LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | GPE (MacNab): 91% excellent or good, 5.2% poor | ||

| Neurological deficit | Level: single level, L3–S1 | YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | Recurrence: 2.7% | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Complications: 2.7% | ||||

| Sequestration | Re-operations: 4.6% | ||||

| Previous operation (same level) | |||||

| Tzaan [60] | Inclusion criteria | n = 134 ♀56 ♂78, mean 38 years, range 22–71 | Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (TPELD) | Follow-up: mean 38 months (range 3–36), 0% non-responders | |

| Pain in leg and back | Type: all LDH | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (modified MacNab): 28% excellent, 61% good, 3.7% poor | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: multiple level n = 20, L2–S1 | Instrumentation not specified | Recurrence: 0.7% | ||

| Sequestration | Complications: 6.0% | ||||

| Spinal stenosis | Re-operations: 4.5% | ||||

| Calcified disc | |||||

| Segmental instability | |||||

| Cauda syndrome | |||||

| Wojcik [62] | Inclusion criteria | n = 43 ♀25 ♂18, mean 30 years | Endoscopically assisted percutaneous lumbar discectomy | Follow-up: 18 months, 16.3% non-responders | |

| Radiculopathy | Type: not specified | Pure intradiscal technique | GPE (unclear instrument): 64% good, 36% satisfied, 0% poor | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Level: not specified | Modified Hijikata instrumentation | Complications: not specified | ||

| Sequestration | Re-operations: not specified | ||||

| Chronic back pain | |||||

| Yeung and Tsou [65] | Inclusion criteria | n = 307 ♀102 ♂205, mean 42 years, range 18–72 | Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation | Follow-up: mean 19 months (range 12–?), 8.8% non-responders | Possible patient overlap with other study [65] |

| Prior disc surgery n = 31 | Type: all LDH | Intradiscal and intracanal technique | GPE (MacNab): 84% excellent or good, 9.3% poor | ||

| Radiculopathy | Level: single level, L2–S1 | YESS, Richard Wolf instrumentation | Recurrence: 0.7% | ||

| Neurological deficit | Complications: 3.9% | ||||

| Exclusion criteria | Re-operations: 4.6% | ||||

| Sequestration | |||||

| Central and lateral stenosis |

? unknown, is not described in the study

Intervention as quoted in original article, Post-tension signs denotes positive tension signs (straight leg raising test or contralateral straight leg raising test)

Outcomes: S statistically significant, NS not statistically significant, PS patient satisfaction, MacNab MacNab score as described by MacNab [39]. The sum of ‘excellent’ and ‘good’ outcomes are labelled ‘satisfactory’, GPE global perceived effect, S/S-score Suezawa and Schreiber score [40], ODI Oswestry disability index [38], PROLO prolo functional-economic outcome rating scale [44]

Type of studies and methodological quality

A total of six prospective controlled studies and two retrospective controlled studies were included. Of the six prospective controlled studies, only the study by Hermantin et al. [11] was considered to have a low RoB. The other five prospective controlled studies and two retrospective controlled were labelled as a high RoB (the full RoB assessment is available upon request).

Furthermore, 12 studies were designed as prospective cohort (without control group) and there were 19 retrospective studies (also without control group). When it was unclear whether the study was prospective or retrospective, the study was considered retrospective.

Of the six prospective controlled studies, four compared transforaminal endoscopic surgery with open discectomy or microdiscectomy. All four were reported as randomized trials, but in three of them the method of randomization was inadequate. Mayer and Brock [39] did not describe the randomization method at all, and Krappel et al. [31] and Ruetten et al. [47] did not randomize, but allocated patients alternately to transforaminal endoscopic surgery or microdiscectomy. Only in the low RoB study by Hermantin et al. [11] randomization was adequately performed in 60 patients with non-sequestered lumbar disc herniations. However, the generalizability of this study is poor because patients with a specific type of herniated disc were selected and results are consequently not directly transferable to all patients with lumbar disc herniations.

Outcomes

What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery?

No randomized controlled trials were identified. Outcomes of 31 observational, non-controlled studies are presented in Table 8. The median overall improvement of leg pain (VAS) was 88 (range 65–89%), global perceived effect (MacNab) 85 (72–94%), return to work of 90%, recurrence rate 1.7%, complications 2.8% and re-operations 7%.

What is the effectiveness of the older intradiscal technique and the more recently developed intracanal technique?

No randomized controlled trials were identified. In Table 9 the results of 14 non-controlled studies describing the intradiscal technique and 16 non-controlled studies describing the intracanal technique are presented. The median leg pain improvement (VAS) was 83% (78–88%) for the intradiscal versus 88% (65–89%) for the intracanal technique and the results for global perceived effect were (MacNab) 85% (78–89%) versus 86% (72–93%), respectively; and other outcomes are listed in Table 9.

What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery for the different types of herniations (mere lateral herniations versus central herniations versus all types of lumbar disc herniations)?

No randomized controlled trials were identified. Six non-controlled studies described surgery for far-lateral herniations, one for central herniations and in 15 studies all types of herniations were included. The median GPE (MacNab) was 86% (85–86%) for lateral herniations, 91% for central herniations and 83% (79–94%) for all types of herniations. Other outcomes are listed in Table 10.

-

2.

What is the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery compared to open microdiscectomy?

Six controlled studies (n = 720) were identified that compared transforaminal endoscopic to open microdiscectomy. Four of them were prospective and two retrospective studies.

Table 8.

Overall outcome, non-controlled studies

| Outcome measure (instrument) | Studies (patients) | Outcome median (min–max) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain leg (VAS) | 7 (n = 1,558) | 88% (65–89%) improvement |

| Pain back (VAS) | 5 (n = 1,401) | 74% (13–84%) improvement |

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 3 (n = 144) | 70% (63–85%) improvement |

| GPE (MacNab) | 15 (n = 2,544) | 85% (72–94%) satisfactory |

| 6% (0.3–27%) poor | ||

| Functional status (ODI) | 3 (n = 624) | 83% (74–90%) improvement |

| Patient satisfaction | 3 (n = 181) | 78% (75–92%) satisfactory |

| Return to work | 5 (n = 757) | 90% (67–95%) |

| Recurrence | 13 (n = 2,612) | 1.7% (0–12%) |

| Complication | 28 (n = 6,336) | 2.8% (0–40%) |

| Re-operation | 28 (n = 4,135) | 7% (0–27%) |

Table 9.

Intradiscal and intracanal techniques, outcomes non-controlled studies

| Outcome measure (instrument) | Studies | Outcome median (min–max) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure intradiscal technique 14 studies (n = 1,267) intradiscal technique | ||

| Pain leg (VAS) | 2 (n = 66) | 83% (78–88%) improvement |

| Pain back (VAS) | 1 (n = 25) | 75% improvement |

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 1 (n = 66) | 85% improvement |

| GPE (MacNab) | 3 (n = 279) | 85% (78–89%) satisfactory |

| 6.5% (3.7–11%) poor | ||

| Recurrence | 3 (n = 217) | 0.7% (0–5.1%) |

| Complication | 12 (n = 1,206) | 5.3 % (0–40%) |

| Re-operation | 14 (n = 1,267) | 7.5% (1.3–30%) |

| Intracanal technique 16 studies (n = 4,985) | ||

| Pain leg (VAS) | 5 (n = 1,524) | 88% (65–89%) improvement |

| Pain back (VAS) | 4 (n = 1,408) | 70% (13–84%) improvement |

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 2 (n = 78) | 67% (63–70%) improvement |

| GPE (MacNab) | 12 (n = 2,292) | 86% (72–93%) satisfactory |

| 6% (0.3–9.3%) poor | ||

| Recurrence | 10 (n = 2,395) | 3.2% (0–12%) |

| Complication | 17 (n = 5,362) | 2.1% (0–17%) |

| Re-operation | 15 (n = 3,098) | 4.6% (0–27%) |

Outcomes: MacNab MacNab score as described by MacNab [39]. The sum of ‘excellent’ and ‘good’ outcomes are labelled ‘satisfactory’, GPE global perceived effect

Table 10.

Outcomes of improvement in lateral herniations, central herniations and all types of herniations

| Outcome measure (instrument) | Studies | Outcome median (min–max) |

|---|---|---|

| Type: far-lateral LDH 6 studies (n = 214) | ||

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 4 (n = 167) | 82% (63–88%) improvement |

| GPE (MacNab) | 2 (n = 52) | 86% (85–86%) satisfactory |

| 9.8% (8.6–11%) poor | ||

| Functional status (ODI) | ||

| Recurrence | 2 (n = 76) | 2.6% (0–5.1%) |

| Complication | 5 (n = 214) | 5.1% (0–17%) |

| Re–operation | 5 (n = 214) | 8.0% (7.6–11%) |

| Type: central LDH 1 study (n = 71) | ||

| GPE (MacNab) | 1 (n = 71) | 91% satisfactory |

| 12% poor | ||

| Complication | 1 (n = 71) | 2.7% |

| Re-operation | 1 (n = 71) | 4.6% |

| Type: all LDH 15 studies (n = 3,067) | ||

| Pain leg (VAS) | 4 (n = 1,374) | 88% (69–89%) improvement |

| Pain back (VAS) | 4 (n = 1,374) | 70% (13–84%) improvement |

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 1 (n = 43) | 70% improvement |

| GPE (MacNab) | 9 (n = 1,810) | 83% (79–94%) satisfactory |

| 4.6% (0.3–9.3%) poor | ||

| Recurrence | 9 (n = 2,201) | 3.6% (0–12%) |

| Complication | 15 (n = 2,934) | 4.9% (0–45%) |

| Re-operation | 15 (n = 2,934) | 5.6% (2.3–27%) |

LDH lumbar disc herniation, Type in transversal section, subdivided in central, paramedian, foraminal and extraforaminal herniations

Only one randomized controlled trial (n = 60) with a low RoB was identified that compared pure intradiscal technique with open laminotomy [11]. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. The pain reduction in the transforaminal endoscopic surgery group was 71 versus 82% in the open laminotomy group after on average 32 months follow-up. The overall improvement was 97 versus 93%, re-operation rate 6.7 versus 3.3% and complication rate 6.7 versus 0%, respectively. Overall, the controlled studies found no differences in outcomes: leg pain reduction in the transforaminal endoscopic surgery group was 89 versus 87% in the open microdiscectomy group, overall improvement (GPE) was 84 versus 78%, re-operation rate 6.8 versus 4.7% and complication rate 1.5 versus 1.0%, respectively (Table 11). In none of the studies, there were any statistically significant differences between the intervention groups on pain improvement and global perceived effect. Ruetten et al. [47] (n = 200) reported statistically significant differences on return to work, but this was a secondary outcome and it was unclear how many subjects in each group had work and if groups were comparable regarding work status and history of work absenteeism at baseline.

Table 11.

Outcomes of improvement of transforaminal endoscopic versus open microdiscectomy

| Outcome measure (instrument) | Studies | Outcome median (min–max) |

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic (index) versus open microdiscectomy (control) | ||

| Pain leg (VAS) | 1 (n = 200) | Index 89% improvement |

| Control 87% improvement | ||

| Pain back (VAS) | 1 (n = 200) | Index 42% improvement |

| Control −8.3% improvement | ||

| Pain (region not specified) (VAS) | 1 (n = 60) | Index 71% improvement |

| Control 82% improvement | ||

| GPE (MacNab/other) | 5 (n = 1,102) | Index 84% (70–97%) satisfactory |

| 1.7% (0–5.4%) poor | ||

| Control 78% (65–93%) satisfactory | ||

| 3.3% (0–15%) poor | ||

| Recurrences | 4 (n = 1,182) | Index 5.7% (5–6.6%) |

| Control 2.9% (0–6.8%) | ||

| Complications | 6 (n = 1,302) | Index 1.5% (0–6.7%) |

| Control 1.0% (0–12%) | ||

| Re-operations | 6 (n = 1,302) | Index 6.8% (3.3–15%) |

| Control 4.7 % (0–11.5%) | ||

I index intervention, C control intervention

In one study, transforaminal endoscopic surgery was compared with the same operation combined with chymopapain, and one study compared endoscopic surgery with chemonucleolysis and automated discectomy (Table 4).

Discussion

In the current review, all available evidence regarding the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery was identified and systematically summarized. We identified 1 randomized controlled trial, 7 non-randomized controlled trials and 31 observational studies. The methodological quality of these studies was poor. The eight trials did not find any statistically significant differences in leg pain reduction between the transforaminal endoscopic surgery group (89%) and the open microdiscectomy group (87%); overall improvement (84 vs. 78%), re-operation rate (6.8 vs. 4.7%) and complication rate (1.5 vs. 1%), respectively. We conclude that current evidence on the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery is poor and does not provide valid information to either support or refute using this type of surgery in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations. High-quality randomized controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes are direly needed.

This study has a number of limitations that should be considered when drawing conclusions regarding the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery for lumbar disc herniations. The included studies in this review were heterogeneous with regard to the selection of patients, the indications for surgery, the surgical techniques used and the duration of follow-up. Furthermore, different outcome measures were used in the studies and different instruments used for the same outcomes. Below we will elaborate on the most important sources of heterogeneity in more detail.

Selection of patients

Patient selection and in/exclusion criteria were often not clearly described. Amongst others, this includes physical examinations, radiological findings, the period and type of pre-operative therapies and duration of symptoms. In most studies, patients received some type of preoperative conservative treatment for a few months, but the exact content of the conservative treatment was not specified. Also, duration of symptoms before surgery differed amongst studies and in some studies patients with acute onset (<2 weeks) of complaints were also included. In some studies only ‘virgin discs’ were included, whilst in others a previous disc operation was not an exclusion criterion or it was not mentioned if patients with a previous disc operation were excluded or not. In two studies only recurrent herniations after open microdiscectomy were treated with transforaminal endoscopic surgery [3, 17]. Some studies included only lateral or central herniations, whereas others included all herniations. Given this, there is much heterogeneity in patient selection between the studies which hinders comparability between studies.

Techniques

Indications for endoscopic surgery have changed over time with the introduction of new techniques, scopes and instruments. Initially non-contained, sequestered and central herniations were exclusion criteria for endoscopic surgery and L5–S1 level herniations were not always possible to reach as the diameter of the foramen intervertebral decreases in the lumbar area from cranial to caudal [46]. In the earlier studies of transforaminal endoscopic surgery, discectomy was performed through a fenestration in the lateral annulus and the focus was limited on central debulking and reduction in intradiscal pressure. Later studies described that the hernia was extracted from the spinal canal with or without an intradiscal debulking. We found comparable outcomes for these intradiscal and intracanal techniques. However, one could debate whether these procedures are really two different techniques. The main distinction is a 10° difference in direction and may be within the limits of measurement error and anatomical variation. Far-lateral herniations occur in 3–11% of lumbar disc herniations and usually cause severe sciatic pain [1, 2, 43, 44]. Some reports mentioned more difficulty to assess an extraforaminal herniated lumbar disc through an open procedure and it is often associated with the substantial bone removal [35]. Because transforaminal endoscopic surgery is a posterolateral approach to the spine, lateral herniations might be more easily reached [60]. With lateral herniations, the angle of the instruments should be steeper and, thus, the insertion closer to the midline [6, 19]. We compared the effect of transforaminal endoscopic surgery for lateral herniations with central and all herniations. All outcomes were comparable.

Methodological quality

Most studies had major design weaknesses and the quality of the identified studies was poor, indicating that studies had a high RoB. Only one adequately randomized controlled trial was identified. In most studies, randomization was not performed at all, not performed adequately or not described adequately. Obviously, patients and surgeons cannot be blinded for the surgical intervention. However, many other important quality items were also not met by the majority of studies. Although transforaminal endoscopic surgery for lumbar disc herniation was introduced about 30 years ago and many patients have undergone this intervention since its introduction, only one randomized controlled trial with a low RoB has been published. Only high-quality, randomized controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes comparing transforaminal endoscopic surgery to other surgical techniques for lumbar disc herniations can provide strong evidence regarding its effectiveness. Preferably, these trials should be conducted by independent research institutes.

Outcome measures

The most frequently used outcome measures in the included studies are the VAS score for pain and the MacNab score for global perceived effect. To compare the VAS scores across studies, we calculated the percentage of improvement between the postoperative and preoperative scores. The MacNab score is a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (excellent); 2 (good), 3 (fair) to 4 (poor). In most studies ‘excellent’ and ‘good’ were combined and labelled ‘satisfactory’. Although a close inspection of the score ‘good’ on the MacNab, reveals that patients still have occasionally ongoing symptoms, sufficient to interfere with normal work or capacity to enjoy leisure activities [37]. We considered labelling this as a ‘satisfactory’ outcome was somewhat too positive. Therefore, whenever possible, we presented the original MacNab scores. Although some studies used validated outcomes (e.g. the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire for low back pain-specific functional disability) others used non-validated outcomes, or did not describe at all how disability and improvement were measured. Future trials should use valid and reliable instruments to measure the primary outcomes.

Adverse effects

Recurrences

Eighteen studies reported recurrence rates of lumbar disc herniations, but the definition of recurrence varied. In this review, we defined a recurrence as a re-appearance of a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation at the same level after a pain-free interval of longer than a month. When in a study the symptomatic hernia appeared within a month, we considered it a recurrence. The median recurrence rate of included studies was 1.7% (range 0–12%). The reported recurrence rate in the literature of open microdiscectomy is similar with reported ranges from 5 to 11% [60]. The controlled studies found no significant difference in recurrences between the two techniques.

Re-operation

In the observational studies, the median re-operation rate was 7% (0–27%). The controlled studies found no significant differences in re-operation percentages between endoscopic transforaminal surgery and open microdiscectomy (6.8 vs. 4.7%). As in most surgical interventions, adequate patient selection and accurate diagnosis seem very important. Most common cause for re-operations was persistent complaints due to missed lateral bony stenosis and remnant fragments [23].

Complications

One of the suggested advantages of transforaminal endoscopic surgery compared with open microdiscectomy is a lower complication rate [28]. Because of the small incision and minimal internal tissue damage, the revalidation period is supposed to be shorter and scar tissue minimised [29]. In the current review, we found no severe neurological injury and a mean percentage of complications after transforaminal endoscopic surgery of 2.8%. There were no substantial differences in serious complications between endoscopic surgery and open microdiscectomy. Most reported complications were transient dysaesthesia or hypaesthesia. However, it has to be noted that none of the included studies was specifically designed for the assessment of adverse effects, and, therefore, these results have to be interpreted cautiously; also, disadvantages have been reported. Transforaminal endoscopic surgery has a steep learning curve that requires patience and experience, especially for those unfamiliar with percutaneous techniques. In some studies, the patients operated at the beginning of the learning curve had worse outcome [10, 20, 26, 56, 60]. Some patients may experience local anaesthesia as a disadvantage. In three studies, the operations were performed under general anaesthesia [47, 48, 57]. Comprehensive preoperative information about the intervention and permanent communication and constant observation during the operation is of major importance.

Future research

Only randomized controlled trials that are adequately designed, conducted and reported and that have a low RoB will provide sufficient evidence regarding the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery for lumbar disk herniation. High-quality, randomized controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes that compare the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery with open microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniations are needed. The short hospital stay, shorter revalidation period and earlier return to work may result in an economic advantage, although this has never been evaluated. Economic evaluations should be performed alongside these trials to assess the cost-effectiveness and cost utility of transforaminal endoscopic surgery.

Conclusion

This systematic review assessed the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery. Of the 39 studies included in this review, most studies had major design weaknesses and were considered having a high RoB. Only one randomized controlled trial was identified, but this trial had poor generalizability. No significant differences in pain, overall improvement, patient satisfaction, recurrence rate, complications and re-operations were found between transforaminal endoscopic surgery and open microdiscectomy. Current evidence on the effectiveness of transforaminal endoscopic surgery is poor and does not provide valid information to either support or refute using this type of surgery in patients with symptomatic lumbar disc herniations.

Conflict of interest statement

For this review the authors received a grant from The Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), Diemen, The Netherlands.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Abdullah AF, Ditto EW, III, Byrd EB, et al. Extreme-lateral lumbar disc herniations. Clinical syndrome and special problems of diagnosis. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:229–234. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.41.2.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah AF, Wolber PG, Warfield JR, et al. Surgical management of extreme lateral lumbar disc herniations: review of 138 cases. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:648–653. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn Y, Lee SH, Park WM, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for recurrent disc herniation: surgical technique, outcome, and prognostic factors of 43 consecutive cases. Spine. 2004;29:E326–E332. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000134591.32462.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspar W. A new surgical procedure for lumbar disk herniation causing less tissue damage through a microsurgical approach. Adv Neurosurg. 1977;4:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu JC (2004) Evolving transforaminal endoscopic microdecompression for herniated lumbar discs and spinal stenosis. Surg Technol Int 13:276–286 [PubMed]

- 6.Choi G, Lee SH, Bhanot A, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy for extraforaminal lumbar disc herniations: extraforaminal targeted fragmentectomy technique using working channel endoscope. Spine. 2007;32:E93–E99. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000252093.31632.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditsworth DA (1998) Endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy and reconfiguration: a posterolateral approach into the spinal canal. Surg Neurol 49:588–597 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Eustacchio S, Flaschka G, Trummer M et al (2002) Endoscopic percutaneous transforaminal treatment for herniated lumbar discs. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 144:997–1004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Forst R, Hausmann B. Nucleoscopy—a new examination technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1983;101:219–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00436774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haag M. Transforaminal endoscopic microdiscectomy. Indications and short-term to intermediate-term results. Orthopade. 1999;28:615–621. doi: 10.1007/s001320050392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermantin FU, Peters T, Quartararo L, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing the results of open discectomy with those of video-assisted arthroscopic microdiscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:958–965. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199907000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hijikata S (1989) Percutaneous nucleotomy. A new concept technique and 12 years’ experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res 238:9–23 [PubMed]

- 13.Hochschuler SH (1991) Posterior lateral arthroscopic microdiskectomy. Semin Orthop 6:113–114

- 14.Hoogland T (2003) Transforaminal endoscopic discectomy with forminoplasty for lumbar disc herniation. Surg Tech Orthop 1–6

- 15.Hoogland T, Scheckenbach C (1998) Die endoskopische transforminale diskektomie bei lumbalen bandscheibenforfallen. Orthop Prax 34:352–355

- 16.Hoogland T, Schubert M, Miklitz B, et al. Transforaminal posterolateral endoscopic discectomy with or without the combination of a low-dose chymopapain: a prospective randomized study in 280 consecutive cases. Spine. 2006;31:E890–E897. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245955.22358.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoogland T, van den Brekel-Dijkstra K, Schubert M, et al. Endoscopic transforaminal discectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a prospective, cohort evaluation of 262 consecutive cases. Spine. 2008;33:973–978. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8ade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iprenburg M (2007) Transforaminal endoscopic surgery—technique and provisional results in primary disc herniation. Eur Musculoskelet Rev 73–76

- 19.Jang JS, An SH, Lee SH. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of foraminal and extraforaminal lumbar disc herniations. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:338–343. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000204500.14719.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kafadar A, Kahraman S, Akboru M. Percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy: a critical appraisal. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006;49:74–79. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kambin P (1988) Percutaneous lumbar discectomy. Current practice. Surg Rounds Orthop 31–35

- 22.Kambin P, Gellman H. Percutaneous lateral discectomy of the lumbar spine: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop. 1983;174:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kambin P. Arthroscopic microdiscectomy. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(92)90058-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kambin P, O’Brien E, Zhou L et al (1998) Arthroscopic microdiscectomy and selective fragmentectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 347:150–167 [PubMed]

- 25.Kambin P, Zhou L (1997) Arthroscopic discectomy of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Kim MJ, Lee SH, Jung ES, et al. Targeted percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic diskectomy in 295 patients: comparison with results of microscopic diskectomy. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinght M, Goswami A, Patko JT (1999) Endoscopic laser foraminoplasty and a aware-state surgery: a treatment concept and 2-year outcome analyses. Arthroskopie 12:62–73

- 28.Knight MT, Ellison DR, Goswami A, et al. Review of safety in endoscopic laser foraminoplasty for the management of back pain. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2001;19:147–157. doi: 10.1089/10445470152927982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knight MT, Goswami A, Patko JT, et al. Endoscopic foraminoplasty: a prospective study on 250 consecutive patients with independent evaluation. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2001;19:73–81. doi: 10.1089/104454701750285395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight MT, Vajda A, Jakab GV, et al. Endoscopic laser foraminoplasty on the lumbar spine—early experience. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1998;41:5–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krappel F, Schmitz R, Bauer E, et al. Open or endoscopic nucleotomy? Results of a prospective, controlled clinical trial with independent follow up, MRI and special reference to cost effectiveness. Offene oder endoskopische nukleotomie—Ergebnisse einer kontrollierten klinischen studie mit unabhangiger nachuntersuchung, MRT und unter besonderer berucksichtigung der kosten-nutzen-relation. Orthop Prax. 2001;37:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SH, Chung SE, Ahn Y, et al. Comparative radiologic evaluation of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy and open microdiscectomy: a matched cohort analysis. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Kim SK, Lee SH et al (2007) Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for migrated disc herniation: classification of disc migration and surgical approaches. Eur Spine J 16:431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lee SH, Lee SJ, Park KH et al (1996) Comparison of percutaneous manual and endoscopic laser diskectomy with chemonucleolysis and automated nucleotomy. Orthopade 25:49–55 [PubMed]

- 35.Lew SM, Mehalic TF, Fagone KL. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of far-lateral and foraminal lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:216–220. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.94.2.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leu H, Schreiber A (1991) Percutaneous nucleotomy with disk endoscopy—a minimally invasive therapy in non-sequestrated intervertebral disk hernia. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax 80:364–368 [PubMed]

- 37.Macnab I. Negative disc exploration. An analysis of the causes of nerve-root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:891–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathews HH. Transforaminal endoscopic microdiscectomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1996;7:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]