Abstract

Recurrent low back pain (recurrent LBP) is a common condition, however, it is unclear if uniform definitions are used in studies investigating the prevalence and management of this condition. The aim of this systematic review was to identify how recurrent LBP is defined in the literature. A literature search was performed on MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PEDro. Studies were considered eligible if they investigated a cohort of subjects with recurrent LBP or if they were measuring the prevalence of recurrent LBP. Two independent reviewers assessed inclusion of studies and extracted definitions of recurrent LBP. Forty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. The majority of studies (63%) gave an explicit definition of recurrent LBP; however, the definitions varied greatly and only three definitions for recurrent LBP were used by more than one study. The most common feature given as part of the definition was the frequency of previous episodes of low back pain. Only 8% (3/36) of studies used previously recommended definitions for recurrent LBP. Large variation exists in definitions of recurrent LBP used in the literature, making interpretation of prevalence rates and treatment outcomes very difficult. Achieving consensus among experts in this area is required.

Keywords: Recurrent low back pain, Non-specific low back pain, Definition, Review

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is reported to run a recurrent course in the majority of patients [1, 2]. This means that following an episode of low back pain it is likely that a patient will have further episodes of pain [3] causing suffering for the patient and time loss from work. A number of treatments have been developed to reduce the risk of recurrent low back pain (recurrent LBP) [4–11] with clinical trials conducted to evaluate how effective treatments are in patients with recurrent LBP [12–19].

The area of recurrent LBP is complex; as is the terminology used to describe it. For example, the term ‘recurrent LBP’ is used in many different ways by clinicians and researchers creating much confusion when trying to study this condition. One use of the term recurrent LBP is to describe an outcomeevent (e.g., a recurrence of an episode of LBP). This is applicable to a study design where patients with LBP are given a treatment and then followed over time to determine if they have a recurrence of their original LBP. A second use of the term recurrent LBP is to describe a patientpopulation (e.g., patients with recurrent LBP). This is applicable when recurrent LBP is used as an inclusion criterion for a study investigating treatments for patients with recurrent LBP and we are then interested in how the authors define this type of patient.

While the two uses of recurrent LBP terminology may sound similar, they have quite different meanings. For example, some patients, after recovering from an episode of LBP, will have a recurrence at some future time. However, many researchers and clinicians would say a single episode of recurrence does not constitute the condition “recurrent LBP” but instead the patient has to experience a certain number of recurrences within a defined time period to fit this category.

We recently conducted a systematic review that investigated how recurrence as an outcome event was defined in the LBP literature. We found that definitions of recurrence of an episode of LBP varied widely making comparisons between studies difficult, if not impossible. However, to date, no study has comprehensively evaluated the definitions used in the literature to define recurrent LBP as a patient population.

It is important to clearly define recurrent LBP as a patient population in order to study treatment efficacy and prognosis for this group of patients. Without an agreed definition it is difficult to interpret the results of trials that evaluate the management of recurrent LBP or observational studies that attempt to estimate the prevalence of recurrent LBP or its prognosis. The only published recommended definition for recurrent LBP that we are aware of following a comprehensive search is that by von Korff in 1994: ‘back pain present on less than half the days in a 12-month period, occurring in multiple episodes over the year’ [2]. However, it is unclear if this definition is being used in research.

The purpose of this systematic review therefore, is to explore and summarise the definitions of recurrent LBP (as a patient population) that are currently used in the literature.

Methods

Search strategy

Identification of potential studies for inclusion was performed via a general search of Medline (1950 to November 2008), EMBASE (1974 to November 2008), CINAHL (1982 to November 2008), AMED (1985 to November 2008), and PEDro (1929 to November 2008). Keywords describing low back pain (low back pain OR back pain OR backache OR low back injury OR sciatica OR lumbago) AND recurrent (recurren$) were used to identify papers in which recurrent LBP was studied.

Inclusion criteria

To be included studies needed to meet all of the following criteria.

A prospective, cohort study and/or randomised controlled trial

Study population of patients with non-specific LBP.

The study provides a definition of “recurrent LBP”, e.g., as an inclusion criterion in a trial or as a case definition in a prevalence study.

Exclusion criteria

Papers written in non-English languages where a translation cannot be arranged

Papers addressing surgical management of LBP.

Article inclusion

One reviewer (TS) applied the inclusion criteria to select the potentially relevant trials from the titles, abstracts, and key words of the references retrieved by the literature search. Then, two independent reviewers (TS and JL) applied the inclusion criteria to any retrieved studies for which inclusion was uncertain. The references of all included studies were checked to ensure that all studies examining recurrent LBP were included. No additional studies were included based on this hand-search process.

Data extraction

The definitions given for recurrent LBP were extracted from each study. The features used in the recurrent LBP definitions (e.g., number of previous episodes, duration of pain, severity of pain, etc.) were identified and the criteria used for each feature were recorded (e.g., at least 3 previous episodes of LBP).

Results

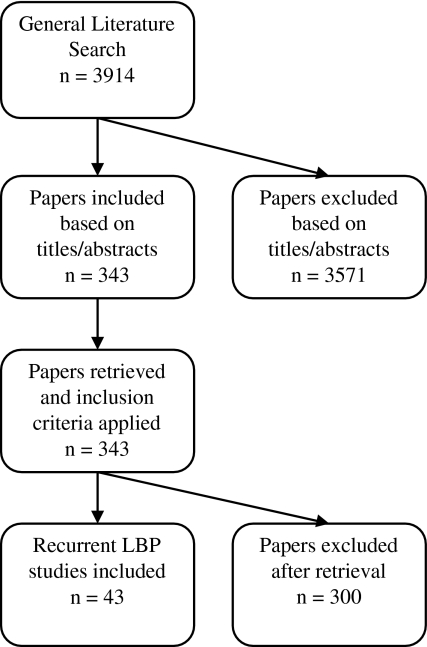

A total of 43 studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1) [12–54]. Thirty studies investigated a patient population with recurrent LBP (definition given in the inclusion criteria of study) [12–19, 21, 22, 25–29, 32–38, 41, 42, 46–50, 52] and 13 studies measured the prevalence of recurrent LBP [20, 23, 24, 30, 31, 39, 40, 43–45, 51, 53, 54].

Fig. 1.

Flow chart describing the results of the literature search

Explicit definitions of recurrent LBP were given in 63% of studies (27/43) [13–19, 22, 24, 27, 29–31, 35, 37, 39–43, 45–47, 49–51, 54]. A comprehensive list of these explicit definitions is given in Table 1. Only three definitions were used by more than one study; one definition was shared by three studies [16, 17, 37], a second definition was shared by two studies [13, 18], and a third definition was shared by two studies [31, 43].

Table 1.

Definitions of recurrent LBP, separated by definition feature, for the 27 studies giving explicit definitions of recurrent LBP

| Studies | Previous LBP | Duration | Severity | Pain course | Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of episodes | Frequency | |||||

| Patient population of recurrent LBP (inclusion criteria) | ||||||

| Bruce [22] | At least one over the last year | LBP resulting in an outpatient visit | ||||

| Cairns [13] | At least one | LBP resulting in alteration in normal activities or care seeking | ||||

| Feuerstein [27] | Pain twice weekly | Minimum of 6 months | ||||

| Harkapaa [29] | At least 2 years | LBP affecting physical capacity to work and resulting in sick leave | ||||

| Jones [14] | Regular LBP involving repeated acute bouts | |||||

| Jones [15] | Repeated acute episodes of LBP experienced as multiple spells | |||||

| Koumantakis [16] | Repeated pain episodes in last year | <6 months in total | ||||

| Koumantakis [17] | Repeated pain episodes in last year | <6 months in total | ||||

| Linton [35] | ≥4 pain episodes over the past year | |||||

| Little [18] | LBP at least once (>3 months previously) | Current LBP ≥3 weeks | LBP resulting in presentation to primary care | |||

| McGorry [37] | Repeated pain episodes over 6 months | <½ of reporting days | ||||

| Müller [41] | Sick leave due to recurrent LBP | |||||

| Nyiendo [42] | Discreet episode of LBP | ≥6 weeks with no LBP | ||||

| Roelofs [19] | ≥2 episodes of LBP symptoms in the past 12 months | ≥2 consecutive days of LBP | ||||

| Stig [46] | >4 weeks of pain in past years with ≥2 weeks of pain currently | |||||

| Symmons [47] | Current LBP with history of previous episodes of LBP | |||||

| Triano [49] | ≤6 episodes of LBP over the past years prior to present episode | 4–6 weeks free of LBP prior to current episode | ||||

| Tsao [50] | LBP >3 months | |||||

| Prevalence of people with recurrent LBP | ||||||

| Burton [24] | 1–6 spells over previous 3 years | |||||

| Hestbaek [30] | >30 days LBP in past year | |||||

| Kääriä [31] | Pain at baseline and f/u | |||||

| Mikkelsson [39] | At least 10 times | |||||

| Moseley [40] | >4 episodes in the last 2 years | |||||

| Raspe [43] | Pain at baseline and f/u | |||||

| Stanford [45] | Pain frequency reported as: about once per month, weekly, more than once per week, on most days | |||||

| Van den Heuvel [51] | 4-point scale (seldom/never, sometimes, regular, prolonged) | Regular/prolonged LBP at two consecutive interviews | ||||

| Yip [54] | LBP for at least 1 day | Pain at baseline and f/u | ||||

f/u Follow-up

There are several features that were commonly used by different studies as part of their definition of recurrent LBP. The most common feature used to define recurrent LBP was the frequency of previous episodes of LBP (14/43 studies) [13–19, 22, 24, 27, 35, 37, 39, 40, 45, 47, 49, 51]. The criteria used to quantify the frequency of previous episodes, however, were very different. For example, Roelofs and colleagues quantified frequency of previous episodes as “≥2 episodes of low back symptoms in past year” [19] while Feuerstein et al. used “pain twice weekly over a minimum period of 6 months” [27]. Some definitions were more general in nature, defining frequency as “multiple spells over the past year” [14] or “repeated pain episodes over the past year” [16, 17]. Other definitions of frequency were related to seeking care; e.g., “at least one previous outpatient visit for low back pain over past year” [22] or “previous presentation to primary care with low back pain within the last 3 months” [18].

Four other features were used by studies as part of their definition of recurrent LBP. These features included specifying the number of previous episodes of LBP (e.g., “at least 10 times” [39]), the duration of pain (e.g., a recurrent episode must last for “≥2 consecutive days with low back pain” [19]), the severity of pain (e.g., “low back pain affecting physical capacity to work and resulting in sick leave” [29]), and the pain course (e.g., “report regular or prolonged pain at two consecutive interviews” [51]). These features were used in 4 [13, 18, 39, 47], 11 [16–19, 27, 29, 30, 37, 46, 50, 54], 5 [13, 18, 22, 29, 41], and 5 [31, 42, 43, 51, 54] studies, respectively. Eleven out of the 27 studies that gave definitions for recurrent LBP combined various definition features [13, 16–19, 22, 37, 51, 54] (e.g., “pain twice weekly [frequency] for at least 6 months [duration]” [27]). von Korff’s recommended definition for recurrent LBP [2] was used by only 3 of 36 studies (giving explicit definitions) [16, 17, 37] published since his 1994 paper.

In only two papers (5%) did the definition of recurrent LBP explicitly differentiate between patients whose episodes of LBP are separated by periods of recovery and those that have flare-ups of LBP but do not fully recover. In these two studies a recovery period of 4–6 weeks [49] and ≥6 weeks [42] between episodes was used.

Discussion

This paper found that less than two thirds of studies gave explicit definitions for recurrent LBP (63%). Studies used a range of different features to define recurrent LBP and for each of these features the criteria varied greatly. The most common feature used to define recurrent LBP was the frequency of previous episodes of LBP and this was reported in only 33% of studies. Only 8% (3/36) of studies (published after 2000) used the previously recommended definition of von Korff [2].

It is clear from the results of this study that there is little agreement on the definition of recurrent LBP. In fact, only three definitions of recurrent LBP were used by more than one study. Not only did studies use different features to define LBP but the criteria for these features also varied remarkably. As an example although frequency of episodes was the most commonly used feature to define recurrent LBP [13–19, 22, 24, 27, 35, 37, 39, 40, 45, 47, 49, 51] the criteria ranged from “at least one episode over past year” [22] to “pain twice weekly” [27]. This demonstrates the importance of reaching a consensus on both the features, and operational criteria for each feature, when defining recurrent LBP. It is likely that the lack of a consensus definition for recurrent LBP has contributed to the different findings with regards to the prevalence [20, 30, 31] and effectiveness of treatments [13, 16, 17, 50] for recurrent LBP reported in the literature.

Not only does variability in definitions of recurrent LBP affect research findings and the ability to translate these findings into clinical practice, but it also affects the clinical treatment of LBP by hindering the ability of multidisciplinary teams to communicate effectively. Rarely is a patient treated by only one health profession over the course of care. Differences in patient category definitions (e.g., recurrent LBP) between team members may negatively influence the treatment of a patient. Therefore, achieving standardised definitions for patient categories such as recurrent LBP is an extremely important first step.

There are two approaches that can be taken to deal with the large variability in definitions of recurrent LBP. The first is to choose the definition that allows measurements with optimal clinimetric properties. The second approach is to aim for consensus on a definition of recurrent LBP among experts in this area. While both approaches appear reasonable, given the diversity of definitions used in the literature and summarised by this review, it appears that reaching expert consensus on a definition for recurrent LBP would be a timely and viable first step. Once consensus is reached, a clinimetric analysis of the definition can follow. In the meantime, we would suggest that for future research the following features should be included as part of a definition of recurrent LBP. Firstly the authors should provide a definition of an episode of LBP that includes a definition for the start and end of the episode. We would advocate the de Vet definition (period of LBP lasting more than 24 h preceded and separated by a period of at least 1 month without LBP) [55] as suitable for this purpose. Secondly a definition to classify someone as having recurrent LBP needs to consider the number of previous episodes of LBP and the time span they occurred over (e.g., at least 2 episodes in the past 12 months). These recommendations reflect the opinions of the authors based upon review of the current literature. While they are opinion based; given the diversity of definitions currently being used, any attempt at standardisation would be beneficial.

It is possible that despite the comprehensive nature of our search strategy some studies with definitions of recurrent LBP were missed. However, any further studies included would most likely increase the heterogeneity of our findings not decrease it; therefore it is unlikely that our results would change.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates that large variation exists in definitions of recurrent LBP used in the literature, making interpretation of research in this area difficult. There is a clear need for a consensus to be reached on an appropriate definition for recurrent LBP.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council for funding of Professor Chris Maher’s research fellowship.

References

- 1.Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A, Hadler N, Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A, Hadler N. Recurrence and care seeking after acute back pain: results of a long-term follow-up study. North Carolina Back Pain Project. Med Care. 1999;37:157–164. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korff M. Studying the natural history of back pain. Spine. 1994;19:2041S–2046S. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanton TR, Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, McAuley JH. After an episode of acute low back pain, recurrence is unpredictable and not as common as previously thought. Spine. 2008;33:2923–2928. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818a3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glomsrod B, Lonn JH, Soukop MG, Bo K, Larsen S. “Active back school”, prophylactic management for low back pain: three-year follow-up of a randomized, controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:26–30. doi: 10.1080/165019701300006506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hides JA, Jull GA, Richardson CA. Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for first-episode low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:E243–E248. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonn JH, Glomsrod B, Soukop MG, Bo K, Larsen S. Active back school: prophylactic management for low back pain. Spine. 1999;24:865–871. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199905010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher C. A systematic review of workplace interventions to prevent low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2000;46:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soukop MG, Glomsrod B, Lonn JH, Bo K, Larsen S. The effect of a mensendieck exercise program as secondary prophylaxis for recurrent low back pain. A randomized, controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Spine. 1999;24:1585–1592. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soukop MG, Lonn JH, Glomsrod B, Bo K, Larsen S. Exercises and education as secondary prevention for recurrent low back pain. Physiother Res Int. 2001;6:27–39. doi: 10.1002/pri.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stankovic R, Johnell O. Conservative treatment of acute low-back pain. A prospective randomized trial: McKenzie method of treatment versus patient education in “Mini back school”. Spine. 1990;15:120–123. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stankovic R, Johnell O. Conservative treatment of acute low back pain. A 5-year follow-up of two methods of treatment. Spine. 1995;20:469–472. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brizzi A, Giusti A, Giacchetti P, Stefanelli S, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG. A randomised controlled trial on the efficacy of hydroelectrophoresis in acute recurrences in chronic low back pain patients. Eur Med Phys. 2004;40:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cairns MC, Foster NE, Wright C. Randomized controlled trial of specific spinal stabilization exercises and conventional physiotherapy for recurrent low back pain. Spine. 2006;31:E670–E681. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000232787.71938.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones M, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan V. The efficacy of exercise as an intervention to treat recurrent nonspecific low back pain in adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2007;19:349–359. doi: 10.1123/pes.19.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones MA, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan VB. Recurrent non-specific low-back pain in adolescents: the role of exercise. Ergonomics. 2007;50:1680–1688. doi: 10.1080/00207720601164597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. Trunk muscle stabilization training plus general exercise versus general exercise only: randomized controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain. Phys Ther. 2005;85:209–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA, Koumantakis GA, Watson PJ, Oldham JA. Supplementation of general endurance exercise with stabilisation training versus general exercise only. Physiological and functional outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of patients with recurrent low back pain. Clin Biomech. 2005;20:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, Evans M, Beattie A, Middleton K, Barnett J, Ballard K, Oxford F, Smith P, Yardley L, Hollinghurst S, Sharp D. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008;337:438–441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roelofs PD, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Poppel MN, Jellema P, Willemsen SP, Tulder MW, Mechelen W, Koes BW. Lumbar supports to prevent recurrent low back pain among home care workers: a randomized trial (with consumer summary) Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:685–692. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker A, Kogell K, Donner-Banzhoff N, Basler HD, Chenot JF, Maitra R, Kochen MM. Low back pain patients in general practice: complaints, therapy expectations and care information. Z Allg Med. 2003;79:126–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown FL, Jr, Bodison S, Dixon J. Comparison of diflunisal and acetaminophen with codeine in the treatment of initial or recurrent acute low back strain. Clin Ther. 1986;9:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce B, Lorig K, Laurent D, Ritter P. The impact of a moderated e-mail discussion group on use of complementary and alternative therapies in subjects with recurrent back pain. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burton AK, Clarke RD, McClune TD, Tillotson KM. The natural history of low back pain in adolescents. Spine. 1996;21:2323–2328. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199610150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burton AK, McClune TD, Clarke RD, Main CJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with low back pain attending for manipulative care: outcomes and predictors. Man Ther. 2004;9:30–35. doi: 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cairns MC, Foster NE, Wright CC, Pennington D. Level of distress in a recurrent low back pain population referred for physical therapy. Spine. 2003;28:953–959. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200305010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faber E, Burdorf A, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Miedema HS, Koes BW. Determinants for improvement in different back pain measures and their influence on the duration of sickness absence. Spine. 2006;31:1477–1483. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219873.84232.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feuerstein M, Carter RL, Papciak AS, Feuerstein M, Carter RL, Papciak AS. A prospective analysis of stress and fatigue in recurrent low back pain. Pain. 1987;31:333–344. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90162-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gudavalli MR, Cambron JA, McGregor M, Jedlicka J, Keenum M, Ghanayem AJ, Patwardhan AG, Gudavalli MR, Cambron JA, McGregor M, Jedlicka J, Keenum M, Ghanayem AJ, Patwardhan AG. A randomized clinical trial and subgroup analysis to compare flexion-distraction with active exercise for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1070–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkapaa K, Jarvikoski A, Mellin G, Hurri H, Luoma J, Harkapaa K, Jarvikoski A, Mellin G, Hurri H, Luoma J. Health locus of control beliefs and psychological distress as predictors for treatment outcome in low-back pain patients: results of a 3-month follow-up of a controlled intervention study. Pain. 1991;46:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90031-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Engberg M, Lauritzen T, Bruun NH, Manniche C. The course of low back pain in a general population. Results from a 5-year prospective study. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2003;26:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaaria S, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H, Kirjonen J, Leino-Arjas P, Kaaria S, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H, Kirjonen J, Leino-Arjas P. Persistence of low back pain reporting among a cohort of employees in a metal corporation: a study with 5-, 10-, and 28-year follow-ups. Pain. 2006;120:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaila-Kangas L, Kivimaki M, Harma M, Riihimaki H, Luukkonen R, Kirjonen J, Leino-Arjas P. Sleep disturbances as predictors of hospitalization for back disorders-a 28-year follow-up of industrial employees. Spine. 2006;31:51–56. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000193902.45315.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leroux I, Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R. Psychosocial job factors and the one-year evolution of back-related functional limitations. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30:47–55. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N, Wu B, Wang CW. (Comparison of acupuncture-moxibustion and physiotherapy in treating chronic non-specific low back pain) (Chinese—simplified characters) Zhongguo Linchuang Kangfu (Chin J Clin Rehabil) 2005;9:186–187. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linton SJ, Ryberg M. A cognitive-behavioral group intervention as prevention for persistent neck and back pain in a non-patient population: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2001;90:83–90. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maul I, Laubli T, Klipstein A, Krueger H. Course of low back pain among nurses: a longitudinal study across eight years. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:497–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.7.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGorry RW, Webster BS, Snook SH, Hsiang SM. The relation between pain intensity, disability, and the episodic nature of chronic and recurrent low back pain. Spine. 2000;25:834–841. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellin G, Hurri H, Mellin G, Hurri H. Referred limb symptoms in chronic low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1990;3:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikkelsson LO, Nupponen H, Kaprio J, Kautiainen H, Mikkelsson M, Kujala UM. Adolescent flexibility, endurance strength, and physical activity as predictors of adult tension neck, low back pain, and knee injury: a 25 year follow up study. Br J Sport Med. 2006;40:107–113. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moseley GL. Impaired trunk muscle function in sub-acute neck pain: etiologic in the subsequent development of low back pain? Man Ther. 2004;9:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller WD, Maier V, Bak P, Smolenski UC. Interlocking between medical rehabilitation and professional reintegration of automobile industry workers with back- and joint pain appraisal by results optimization of the rehabilitation-concept (rehabilitation-plan) Physikalische Medizin Rehabilitationsmedizin Kurortmedizin. 2006;16:149–154. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goodwin P, Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goodwin P. Patient characteristics, practice activities, and one-month outcomes for chronic, recurrent low-back pain treated by chiropractors and family medicine physicians: a practice-based feasibility study. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2000;23:239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(00)90170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raspe A, Matthis C, Heon-Klin V, Raspe H, Raspe A, Matthis C, Heon-Klin V, Raspe H. Chronic back pain: more than pain in the back. Findings of a regional survey among insurees of a workers pension insurance fund. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2003;42:195–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salminen JJ, Erkintalo MO, Pentti J, Oksanen A, Kormano MJ. Recurrent low back pain and early disc degeneration in the young. Spine. 1999;24:1316–1321. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199907010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: a population-based approach. Pain. 2008;138:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stig L, Nilsson O, Leboeuf-Yde C. Recovery pattern of patients treated with chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for long-lasting or recurrent low back pain. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2001;24:288–291. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.114362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Symmons DP, Hemert AM, Vandenbroucke JP, Valkenburg HA, Symmons DP, Hemert AM, Vandenbroucke JP, Valkenburg HA. A longitudinal study of back pain and radiological changes in the lumbar spines of middle aged women. I. Clinical findings. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:158–161. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taimela S, Diederich C, Hubsch M, Heinricy M. The role of physical exercise and inactivity in pain recurrence and absenteeism from work after active outpatient rehabilitation for recurrent or chronic low back pain: a follow-up study. Spine. 2000;25:1809–1816. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Triano JJ, Hondras MA, McGregor M. Differences in treatment history with manipulation for acute, subacute, chronic and recurrent spine pain. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1992;15:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsao H, Hodges P. Persistence of improvements in postural strategies following motor control training in people with recurrent low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heuvel SG, Ariens GA, Boshuizen HC, Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, Heuvel SG, Ariens GAM, Boshuizen HC, Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors related to recurrent low-back pain and sickness absence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30:459–467. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heijden G, Bouter LM, Terpstra-Lindeman E, Essers AHM, Waltje EMH, Koke AJA, Roox GM, Waelen AMW. De effectiviteit van tractie bij lage rugklachten (Dutch) Ned T Fysiotherapie (Dutch J Phys Ther) 1991;101:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wickstrom GJ, Pentti J, Wickstrom GJ, Pentti J. Occupational factors affecting sick leave attributed to low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:145–152. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yip YB. The association between psychosocial work factors and future low back pain among nurses in Hong Kong: a prospective study. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7:223–233. doi: 10.1080/13548500120116157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vet HCW, Heymans MW, Dunn KMP DP, Beek AJ, Macfarlane GJ, Bouter LM, Croft PR. Episodes of low back pain: a proposal for uniform definitions to be used in research. Spine. 2002;27:2409–2416. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]