Abstract

Indian hedgehog (Ihh) is essential for embryonic mandibular condylar growth and disc primordium formation. To determine whether it regulates those processes during post-natal life, we ablated Ihh in cartilage of neonatal mice and assessed the consequences on temporomandibular joint (TMJ) growth and organization over age. Ihh deficiency caused condylar disorganization and growth retardation and reduced polymorphic cell layer proliferation. Expression of Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix was low, as was that of collagen II, collagen I, and aggrecan, thus altering the fibrocartilaginous nature of the condyle. Though a disc formed, it exhibited morphological defects, partial fusion with the glenoid bone surface, reduced synovial cavity space, and, unexpectedly, higher lubricin expression. Analysis of the data shows, for the first time, that continuous Ihh action is required for completion of post-natal TMJ growth and organization. Lubricin overexpression in mutants may represent a compensatory response to sustain TMJ movement and function.

Keywords: temporomandibular joint, TMJ, articular disc, fibrocartilage, hedgehog signaling

Introduction

The diarthrodial temporomandibular joint (TMJ) allows for articulation of the mandibular condyle and temporal eminence and is essential for normal jaw function (Shen and Darendeliler, 2005; Wadhwa et al., 2005). The interlocking and articulating surfaces are covered by fibrocartilage, and the intervening joint space is subdivided into upper and lower compartments separated by the articular disc. TMJ development and condyle growth during embryonic and post-natal life involve complex processes that have long been studied and are well-described in their general aspects, but that remain poorly understood mechanistically.

The first overt sign of condyle development is the appearance of chondrocytes within a thickening periosteal region near the mandibular process. The cells become organized in a growth-plate-like structure that is subdivided along its main axis into a fibrous cell layer, a polymorphic progenitor cell zone, a flattened chondrocyte zone, and a hypertrophic chondrocyte zone (Luder et al., 1988). The condyle grows rapidly toward the temporal bone anlagen during embryonic and post-natal life. Interestingly, this elongation process is largely due to appositional growth in which chondroprogenitor cells at the apical polymorphic zone rapidly proliferate and undergo chondrogenesis, and the newly differentiated chondrocytes become apposed onto the underlying condylar cartilaginous tissue (Kantomaa et al., 1994).

The articular disc is a key component of TMJ function, and its development initiates with the formation of a separate, flat mesenchymal condensation located between the condylar head and temporal bone (Frommer, 1964). With increasing embryonic age, the articular disc anlage undergoes rapid growth and acquires a characteristic compacted organization, especially in its medial portion. Flanking upper and lower cavities form and become filled with joint-lubricating fluids, and the disc eventually matures into a definitive fibrocartilage structure (Bhaskar, 1953; Frommer, 1964).

Hedgehog (Hh) proteins are signaling secreted proteins that regulate fundamental processes in pre- and post-natal development. The proteins act on target cells via the cell-surface receptors Patched and Smoothened and in cooperation with primary cilia, and signaling is transmitted by Gli zinc-finger transcription factors (Corbit et al., 2005; Haycraft et al., 2005; May et al., 2005; Koyama et al., 2007). In developing long bones, Indian hedgehog (Ihh) is produced by pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate, regulates chondrocyte proliferation together with parathyroid-hormone-related protein (PTHrP), and induces intramembranous bone collar formation around the diaphysis (Koyama et al., 1996; Lanske et al., 1996; Nakamura et al., 1997; St-Jacques et al., 1999). We previously showed that Ihh is expressed in the mandibular condyle growth plate in mouse embryos, and Ihh receptors and associated signaling molecules are preferentially expressed in condylar fibrous and polymorphic cell layers (Tang et al., 2004; Shibukawa et al., 2007). Analysis of Ihh-null littermates revealed that Ihh signaling is essential for chondroprogenitor cell proliferation, PTHrP expression, and condylar growth (Shibukawa et al., 2007). Unexpectedly, we found that the Ihh-null embryos also displayed severe defects in articular disc and flanking joint cavities (Shibukawa et al., 2007). However, due to the pre-natal death of those Ihh-null embryos, we were unable to monitor and analyze the joint phenotype further, given that TMJ development, growth, and final organization are completed post-natally. Thus, we created conditional mouse mutants deficient in Ihh in cartilage post-natally and determined whether and how the resulting Ihh signaling deficiency affected structural and functional development of TMJ over post-natal growth.

Materials & Methods

Generation of Ihh-deficient Mice

Ihhfl/fl mice were mated with Col2a1-CreER* mice that express CreER under control of cartilage-specific collagen II gene regulatory sequences. The resulting compound Col2a1-CreER*;Ihhfl/fl transgenic mice were phenotypically normal (Maeda et al., 2007). To induce Cre activity, we administered a single injection of 0.2 mg tamoxifen to newborns, and craniofacial specimens were collected from post-natal day 4 (P4), P7, P14, and 8 wks. Genotyping is described in the Appendix. Animal protocols were approved by IACUC.

Hedgehog Reporter Mice

Heterozygous Gli1+/nLacZ mice were kindly provided by Dr. A. Joyner and are widely used as a functional readout of hedgehog signaling range and activation (Ahn and Joyner, 2005). Staining for β-galactosidase was by standard protocols (Madison et al., 2002).

Gene Expression Analysis

Serial parasagittal sections from Col2a1-CreER*;Ihhfl/fl mice and control littermates placed on the same slides were hybridized with antisense or sense 35S-labeled probes (Nagayama et al., 2008). Mouse cDNA clones were: histone H4C (nt. 549-799; AY158963); Sox9 (nt. 116-856; NM_011448); Osterix (nt. 40-1727; NM_130458); collagen I (nt. 233-634; NM_007742); collagen II (nt. 1095-1344; X57982); collagen X (nt. 1302-1816; NM009925); Ihh (nt. 897-1954; MN_010544); and Patched-1 (nt. 81-841; NM_008957).

Results

Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Post-natal Mandibular Condyles

Serial sections of condyles from newborn and 8-week-old wild-type mice were analyzed histomorphologically and by in situ hybridization to gain insights into post-natal condylar organization and Ihh signaling patterns. At each stage examined, the condyles displayed distinct growth-plate-like zones, including: a superficial (sf) layer, a polymorphic (pm) precursor cell layer, a flattened chondrocyte (fc) zone, and a hypertrophic chondrocyte (hc) zone (Figs. 1A, 1D). In neonatal condyles, Ihh transcripts were abundant and clearly appreciable in upper hypertrophic zones, but were undetectable in the polymorphic zone (Appendix Figs. 1, 6). These patterns were maintained in 8-week-old condyles, though Ihh expression levels had decreased (Appendix Fig. 1).

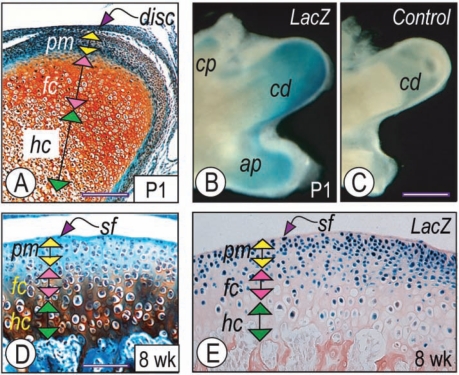

Figure 1.

Ihh activity in post-natal condyles. Serial condylar parasagittal sections from P1 (A) and 8-week-old mice (D) were processed for Safranin O-fast green staining. Vertical double arrowheads in A and D indicate different growth plate zones. Whole condyles (B) or sections (E) from P1 and 8-week-old Gli1-nLacZ reporter mice were processed for detection of b-galactosidase activity. Note in (B) that activity was also detectable in the coronoid process (cp) and angular process (ap), while no activity was detectable in the control wild-type littermate (C). pm, polymorphic zone; fc, flattened chondrocyte zone; hc, hypertrophic zone; cp, coronoid process; ap, angular process; cd, condylar process. Scale bars: 250 mm for A; 8 mm for B-C; and 125 µm for D-E.

To determine range and potential targets of Ihh signaling, we analyzed gene expression of Patched-1 (Ptch-1), a direct transcriptional target of Hh signaling, and used hedgehog-reporter Gli1+/nLacZ mice. Ptch-1 transcripts (Appendix Fig. 1) and reporter activity (Fig. 1E) were very clear in the polymorphic zone and to a much lower extent in the flattened chondrocyte zone, revealing that the polymorphic zone is a major target of Hh signaling activity and action. Whole-mount staining of mandibles from newborn Gli1+/nLacZ (Fig. 1B) and wild-type control littermates (Fig. 1C) confirmed the specificity of reporter expression.

Condyle Zonal Architecture is Deranged in Ihh-deficient Post-natal Mice

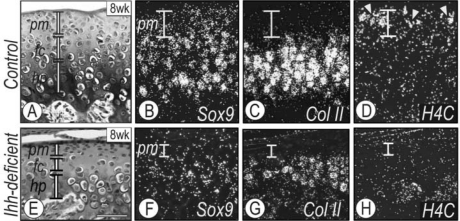

To study Ihh roles, we injected tamoxifen into newborn compound Col2a1-CreER*;Ihhfl/fl mice (heretofore termed ‘Ihh-deficient mice’) and control littermates, and mice were examined at different ages. No major differences were observed in condylar organization in 2-week-old Ihh-deficient mice, but changes became obvious by 8 wks (Fig. 2 and Appendix Figs. 2 and 3). Condylar zonal organization was disrupted, the polymorphic and flattened chondrocyte zones were much thinner, and trabecular bone was much lower compared with controls (Appendix Fig. 3). In addition, chondrocytes with an enlarged diameter were scattered through the tissue, as also were marrow cavities (Appendix Fig. 3). In situ hybridization with control 8-week-old condyles showed that the chondrogenic master gene Sox-9 was expressed in both the polymorphic cell layer and flattened-chondrocyte and collagen II-positive zones (Figs. 2A-2C), patterns similar to those seen at embryonic stages (Rabie and Hägg, 2002; Shibukawa et al., 2007). In Ihh-deficient condyles, however, Sox9 and collagen II expression was significantly decreased (Figs. 2E-2G), in line with the reduced sizes and heights of polymorphic and flattened chondrocyte zones (Fig. 2E). There was also intermingling of collagen II- and collagen X-expressing chondrocytes, indicating that the normal temporal and topological progression of chondrocyte maturation was indeed altered. To examine the polymorphic zone in greater detail, we tested cell proliferation by in situ hybridization analysis of proliferation marker H4C. Proliferating chondro-precursor cells were abundant in the polymorphic zone of control condyles (Fig. 2D), but were markedly decreased and virtually absent in Ihh-deficient condyles (Fig. 2H).

Figure 2.

Growth plate organization is abnormal in Ihh-deficient condylar cartilage. Parasagittal sections from 8-week-old control (A) and Ihh-deficient (E) condyles were stained with Safranin-O/fast green. Serial parasagittal sections from control (B-D) and Ihh-deficient condyles (F-H) were processed for in situ hybridization of: Sox9 (B, F), collagen II (Col II) (C, G), and histone H4C (H4C) (D, H). Vertical bars in B-D and F-H indicated polymorphic zone in condyles. sf, superficial layer; pm, polymorphic zone; fc, flattened chondrocyte zone; hc, hypertrophic zone. Scale bar: 120 µm for A-H.

Expression of Fibrocartilage-characteristic Molecules is Abnormal in Ihh-deficient Condyles

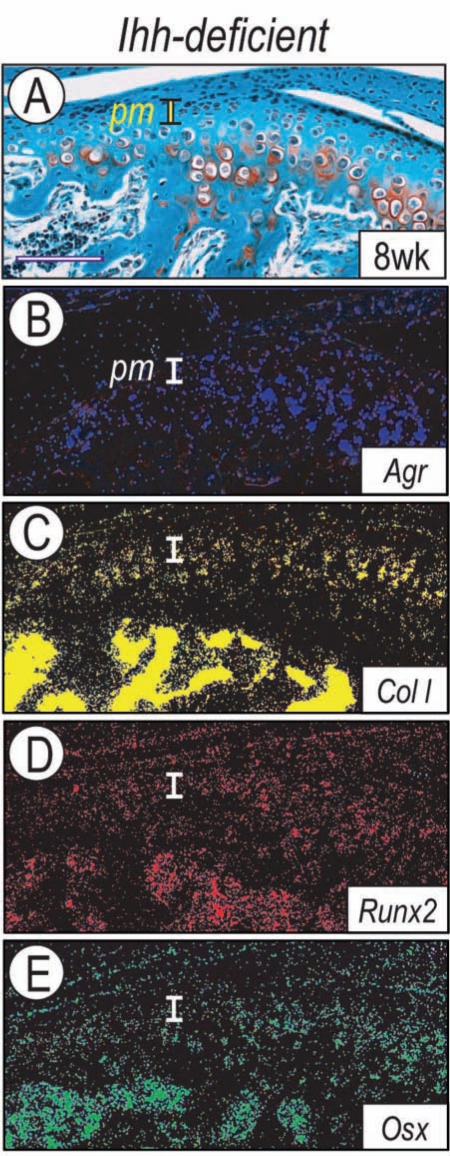

Unlike long bone joints, in which articular cartilage consists of pure hyaline cartilage, the condylar tissue is composed of fibrocartilage, and both aggrecan and collagen I are critical components of its matrix. Thus, we asked whether expression of such matrix genes was affected in post-natal Ihh-deficient mice. In situ hybridization showed that aggrecan and collagen I were expressed in the wild-type polymorphic layer and flattened chondrocyte zone, and less so in the hypertrophic zone (Appendix Figs. 4, 6), as observed prenatally (Silbermann et al., 1990; Fukada et al., 1999). However, both genes were markedly down-regulated in Ihh-deficient cartilage (Figs. 3A-3C). Because collagen I expression is regulated by Osterix and Runx2 in other systems (Komori et al., 1997; Nakashima et al., 2002), we analyzed expression of these master genes. Both Osterix and Runx2 were primarily expressed in the polymorphic layer and flattened chondrocyte zone (Appendix Fig. 4), as seen prenatally (Shibata et al., 2006), but their expression was much lower in Ihh-deficient condyles (Figs. 3D-3E).

Figure 3.

Ihh-deficient condyles display alterations in fibrocartilage characteristics. Serial sections from control (Appendix Fig. 4) and Ihh-deficient (A-E) 8-week-old condyles were processed for Safranin O-fast green staining and in situ hybridization analysis. Note that in controls, aggrecan (Agr) and collagen I (Col I) were expressed in polymorphic and flattened chondrocyte zones along with Runx2 and Osterix (Osx). In Ihh-deficient condyles, however, Runx2, Osterix, aggrecan, and collagen I were decreased. pm, polymorphic zone; fc, flattened chondrocyte zone; hc, hypertrophic zone. Scale bar: 180 µm for A-E.

Partial Disc Ankylosis in Ihh-deficient Condyles

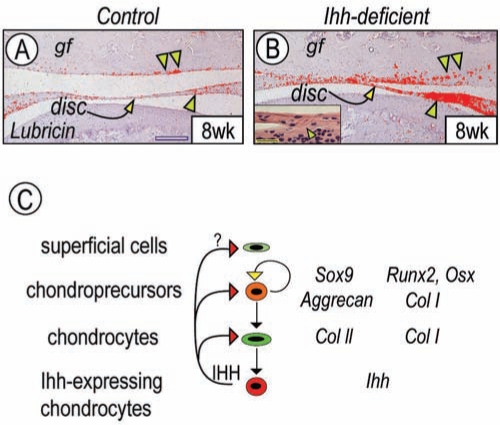

Formation of the condylar joint and filling of upper and lower disc synovial cavities are completed in early mouse post-natal life. Indeed, the discs exhibited a typical central thin region flanked by thicker lateral regions, and the cavities were already fluid-filled in P4 wild-type condyles, and these characteristics did not change with age (Appendix Fig. 5). In condyles of P4 and 8-week-old Ihh-deficient mice, however, we observed partial disc adhesion and fibrous fusion with the articular surface of the condyle and/or glenoid fossa (Appendix Fig. 5, Fig. 4B and inset). These changes were accompanied by significant thickening of the lateral disc regions and by reductions in size/volume of upper and lower cavities (Appendix Fig. 5). Since adhesion or fusion among joint components could restrict jaw movement, we examined the expression of lubricin, a critical anti-adhesion component of joint fluid. Interestingly and surprisingly, lubricin expression was actually significantly up-regulated in disc fibroblasts, synovial cells, and fibrocartilage covering the glenoid fossa in Ihh-deficient mice (Figs. 4B) compared with controls (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Articular disc and synovial cavities were abnormal in Ihh-deficient mice. Serial sections from control (A) and Ihh-deficient (B) 8-week-old condyles were processed for in situ hybridization analysis. The inset in B is a higher-magnification view to show partial disc adhesion and fibrous fusion with the condylar surface (arrowhead) and/or glenoid fossa. gf, glenoid fossa; usc, upper synovial cavity; and lsc, lower synovial cavity. Scale bars: 250 µm for A-B and 35 µm for inset in B. (C) Schematic depicting our current working model for post-natal TMJ. Ihh produced in hypertrophic cells would diffuse and create a long-range signaling gradient reaching the polymorphic and superficial layers. This activity gradient would sustain cell proliferation and strong expression patterns of Sox9, Runx2, and Osx in chondro-precursor cells and appropriate matrix genes. Ihh deficiency would result in concerted decreases in all these parameters, causing fundamental derangements in condylar and joint phenotype, organization, and function.

Discussion

Analysis of our data provides strong evidence that Ihh is required for continuation and completion of condylar and TMJ development, growth, and organization in the post-natal mouse. We found that conditional Ihh ablation in post-natal cartilage causes condylar growth plate disorganization, abnormal gene expression patterns, growth and elongation deficiencies, alterations in articular disc structure and synovial cavities, and partial disc fusion. Given the severity and encompassing nature of these changes, it is clear that continuous Ihh expression and action are absolutely needed to orchestrate and sustain the variety of cellular processes and events that bring about growth and morphogenesis of the TMJ during post-natal life (schematically summarized in our model). The data correlate well with those from our previous studies (Shibukawa et al., 2007) demonstrating that Ihh is equally indispensable for embryonic TMJ development.

Our detailed analysis of post-natal wild-type and mutant mice suggests possible specific roles that Ihh may play in condylar organization and phenotype. In long bone growth plates, the chondrocytes are subdivided in very distinct and well-separated zones in which the cells exhibit equally distinct phenotypes and gene expression patterns. For instance, collagen II is expressed in every zone except the hypertrophic zone, but there is no detectable collagen I expression in any zone. Similarly, prominent expression of Runx2 and Osterix is limited to hypertrophic and post-hypertrophic zones. In the post-natal condylar growth plate, there are zones of morphologically distinct cells, but expression of several of these genes is not as delimited and restricted. We found that Runx2 and Osterix are broadly expressed, and there was clear overlap and co-expression of collagen II and collagen I. In Ihh-deficient condyles, we observed concurrent decreases in the expression of collagen II, collagen I, Runx2, and Osterix, as well as Sox9 and Aggrecan. It appears, therefore, that Ihh has the central role of sustaining and promoting not only the morphological organization of the condylar growth plate, but also the concurrent gene expression of chondrogenic genes (i.e., collagen II, Sox9, etc.) and osteogenic genes (collagen I, Osterix, etc.) (Komori et al., 1997; Akiyama et al., 2002; Nakashima et al., 2002). Ihh would thus be vital for the establishment and maintenance of the somewhat hybrid phenotype and fibrocartilaginous nature of the condyle. This conclusion correlates well with a recent study indicating that experimental mechanical loading of post-natal TMJ leads to robust down-regulation of Ihh as well as down-regulation of Sox9 and Runx2 and thinning of condylar cartilage (Chen et al., 2009).

In our previous study on mouse embryos (Shibukawa et al., 2007), we found that Ihh regulates condylar elongation via promotion of proliferation of progenitor cells in the condylar polymorphic layer in cooperation with PTHrP produced by superficial cells and the polymorphic layer itself. Analysis of our current data with post-natal condyles agrees well with those data and conclusions, and we did observe a major reduction in cell proliferation in post-natal Ihh-deficient condyles. Interestingly, we detected extremely low levels of PTHrP expression in post-natal wild-type or Ihh-deficient condyles (data not shown), leading to the intriguing possibility that post-natal proliferation is mainly driven by direct action of Ihh on precursor cells following long-range diffusion from its site of origin (hypertrophic chondrocytes). This possibility is sustained by our observation that hedgehog target gene Patched1 and hedgehog reporter activity are strongly displayed by polymorphic-layer cells. Long-range Hh action is known to require heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HS-PGs) that facilitate and delimit the diffusion of Hh proteins and promote their interactions with cell-surface receptors; these mechanisms were originally uncovered in Drosophila (Takei et al., 2004) and were subsequently verified in mouse and chick skeletal elements (Koziel et al., 2004; Shimo et al., 2004; Koyama et al., 2007; Ochiai et al., 2009). It remains to be clarified, however, whether Ihh long-range diffusion and direct action on post-natal condylar cell proliferation are indeed mediated by specific HS-PGs.

The disc is a key component of the TMJ, and we now show that deletion of Ihh from chondrocytes at birth results in partial fusion of the articular disc with the condylar surface and/or temporal bones. This is in keeping with our earlier findings that Ihh ablation in embryos nearly prevents both formation of the disc mesenchymal primordium and the appearance of a recognizable disc at later embryonic stages (Shibukawa et al., 2007). It has been reported recently that mice with deletion of Shox2 in the cranial neural-crest-derived ectomesenchyme have a severe disc phenotype as well (Gu et al., 2008), indicating that disc development and morphogenesis involve cooperation and interplay among transcriptional and signaling regulators. The mechanisms underlying the cavitation process of developing synovial joints have been studied in various systems but remain unclear (Pacifici et al., 2005). Interestingly, we found that lubricin is strongly expressed in disc fibroblasts, synovial cells, and temporal bone fibrocartilage. Given that lubricin provides anti-adhesive capacity and lubrication needed for diarthrodial joint functioning (Swann et al., 1985; Schwarz and Hills, 1998), the robust overexpression we observed in the Ihh-deficient TMJ may represent a mechanism to compensate for partial joint fusion and maintain some TMJ function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Alex Joyner for providing the Gli1+/nLacZ hedgehog reporter mice.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants AG025868, AR046000, and AR050560.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Ahn S, Joyner AL. (2005). In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature 437:894-897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. (2002). The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev 16:2813-2828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar SN. (1953). Growth pattern of the rat mandible from 13 days insemination age to 30 days after birth. Am J Anat 92:1-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Sorensen KP, Gupta T, Kilts T, Young M, Wadhwa S. (2009). Altered functional loading causes differential effects in the subchondral bone and condylar cartilage in the temporomandibular joint from young mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 17:354-361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. (2005). Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature 437:1018-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer J. (1964). Prenatal development of the mandibular joint in mice. Anat Rec 150:449-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudaba Y, Tashiro H, Miyata Y, Ohdan H, Yamamoto H, Shibata S, et al. (1999). Oral administration of geranylgeranylacetone protects rat livers from warm ischemic injury. Transplant Proc 31:2918-2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukada K, Shibata S, Suzuki S, Ohya K, Kuroda T. (1999). In situ hybridisation study of type I, II, collagens and aggrecan mRNas in the developing condylar cartilage of fetal mouse mandible. J Anat 195(Pt 3):321-329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Wei N, Yu L, Fei J, Chen Y. (2008). Shox2-deficiency leads to dysplasia and ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint in mice. Mech Dev 125:729-742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. (2005). Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet 1:e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantomaa T, Tuominen M, Pirttiniemi P. (1994). Effect of mechanical forces on chondrocyte maturation and differentiation in the mandibular condyle of the rat. J Dent Res 73:1150-1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, et al. (1997). Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89:755-764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama E, Leatherman JL, Noji S, Pacifici M. (1996). Early chick limb cartilaginous elements possess polarizing activity and express hedgehog-related morphogenetic factors. Dev Dyn 207:344-354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama E, Young B, Nagayama M, Shibukawa Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Iwamoto M, et al. (2007). Conditional Kif3a ablation causes abnormal hedgehog signaling topography, growth plate dysfunction, and excessive bone and cartilage formation during mouse skeletogenesis. Development 134:2159-2169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziel L, Kunath M, Kelly OG, Vortkamp A. (2004). Ext1-dependent heparan sulfate regulates the range of Ihh signaling during endochondral ossification. Dev Cell 6:801-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanske B, Karaplis AC, Lee K, Luz A, Vortkamp A, Pirro A, et al. (1996). PTH/PTHrP receptor in early development and Indian hedgehog-regulated bone growth. Science 273:663-666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luder HU, Leblond CP, von der Mark K. (1988). Cellular stages in cartilage formation as revealed by morphometry, radioautography and type II collagen immunostaining of the mandibular condyle from weanling rats. Am J Anat 182:197-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, Braunstein K, Braunstein E, Gumucio DL. (2002). Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem 277:33275-33283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Nakamura E, Nguyen MT, Suva LJ, Swain FL, Razzaque MS, et al. (2007). Indian Hedgehog produced by postnatal chondrocytes is essential for maintaining a growth plate and trabecular bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:6382-6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May SR, Ashique AM, Karlen M, Wang B, Shen Y, Zarbalis K, et al. (2005). Loss of the retrograde motor for IFT disrupts localization of Smo to cilia and prevents the expression of both activator and repressor functions of Gli. Dev Biol 287:378-389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama M, Iwamoto M, Hargett A, Kamiya N, Tamamura Y, Young B, et al. (2008). Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates cranial base development and growth. J Dent Res 87:244-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Aikawa T, Iwamoto-Enomoto M, Iwamoto M, Higuchi Y, Pacifici M, et al. (1997). Induction of osteogenic differentiation by hedgehog proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237:465-469; erratum in Biochem Biophys Res Commun 247:910, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, et al. (2002). The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 108:17-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai T, Nagayama M, Nakamura T, Morrison T, Pilchak D, Kondo N, et al. (2009). Roles of the primary cilium component polaris in synchondrosis development. J Dent Res 88:545-550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici M, Koyama E, Iwamoto M. (2005). Mechanisms of synovial joint and articular cartilage formation: recent advances, but many lingering mysteries. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 75:237-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabie AB, Hägg U. (2002). Factors regulating mandibular condylar growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 122:401-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz IM, Hills BA. (1998). Surface-active phospholipid as the lubricating component of lubricin. Br J Rheumatol 37:21-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Darendeliler MA. (2005). The adaptive remodeling of condylar cartilage—a transition from chondrogenesis to osteogenesis. J Dent Res 84:691-699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Suda N, Suzuki S, Fukuoka H, Yamashita Y. (2006). An in situ hybridization study of Runx2, Osterix, and Sox9 at the onset of condylar cartilage formation in fetal mouse mandible. J Anat 208:169-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibukawa Y, Young B, Wu C, Yamada S, Long F, Pacifici M, et al. (2007). Temporomandibular joint formation and condyle growth require Indian hedgehog signaling. Dev Dyn 236:426-434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimo T, Gentili C, Iwamoto M, Wu C, Koyama E, Pacifici M. (2004). Indian hedgehog and syndecans-3 coregulate chondrocyte proliferation and function during chick limb skeletogenesis. Dev Dyn 229:607-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbermann M, von der Mark K, Heinegard D. (1990). An immunohistochemical study of the distribution of matrical proteins in the mandibular condyle of neonatal mice. II. Non-collagenous proteins. J Anat 170:23-31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. (1999). Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev 13:2072-2086; erratum in Genes Dev 13:2617, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann DA, Silver FH, Slayter HS, Stafford W, Shore E. (1985). The molecular structure and lubricating activity of lubricin isolated from bovine and human synovial fluids. Biochem J 225:195-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Ozawa Y, Sato M, Watanabe A, Tabata T. (2004). Three Drosophila EXT genes shape morphogen gradients through synthesis of heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Development 131:73-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang GH, Rabie AB, Hägg U. (2004). Indian hedgehog: a mechanotransduction mediator in condylar cartilage. J Dent Res 83:434-438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa S, Embree MC, Kilts T, Young MF, Ameye LG. (2005). Accelerated osteoarthritis in the temporomandibular joint of biglycan/fibromodulin double-deficient mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13:817-827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.