Abstract

Glutathione is a major cellular thiol that is maintained in the reduced state by glutathione reductase (GR), which is encoded by two genes in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; GR1 and GR2). This study addressed the role of GR1 in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) responses through a combined genetic, transcriptomic, and redox profiling approach. To identify the potential role of changes in glutathione status in H2O2 signaling, gr1 mutants, which show a constitutive increase in oxidized glutathione (GSSG), were compared with a catalase-deficient background (cat2), in which GSSG accumulation is conditionally driven by H2O2. Parallel transcriptomics analysis of gr1 and cat2 identified overlapping gene expression profiles that in both lines were dependent on growth daylength. Overlapping genes included phytohormone-associated genes, in particular implicating glutathione oxidation state in the regulation of jasmonic acid signaling. Direct analysis of H2O2-glutathione interactions in cat2 gr1 double mutants established that GR1-dependent glutathione status is required for multiple responses to increased H2O2 availability, including limitation of lesion formation, accumulation of salicylic acid, induction of pathogenesis-related genes, and signaling through jasmonic acid pathways. Modulation of these responses in cat2 gr1 was linked to dramatic GSSG accumulation and modified expression of specific glutaredoxins and glutathione S-transferases, but there is little or no evidence of generalized oxidative stress or changes in thioredoxin-associated gene expression. We conclude that GR1 plays a crucial role in daylength-dependent redox signaling and that this function cannot be replaced by the second Arabidopsis GR gene or by thiol systems such as the thioredoxin system.

Thiol-disulfide exchange plays crucial roles in protein structure, the regulation of enzymatic activity, and redox signaling, and it is principally mediated by thioredoxin (TRX) and glutathione reductase (GR)/glutathione systems (Buchanan and Balmer, 2005; Jacquot et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2008). Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) lines identified in independent screens for alterations in heavy metal tolerance, meristem function, light signaling, and pathogen resistance have been shown to harbor mutations in the gene encoding the first enzyme of glutathione synthesis (Cobbett et al., 1998; Vernoux et al., 2000; Ball et al., 2004; Parisy et al., 2007). Studies on the rml1 mutant, which is severely deficient in glutathione synthesis, define a specific role for glutathione in root meristem function (Vernoux et al., 2000). However, shoot meristem function is regulated in a redundant manner by cytosolic glutathione and TRX (Reichheld et al., 2007), providing a first indication for functional overlap between these thiol-disulfide systems in plant development.

Modifications of cellular thiol-disulfide status may be important in transmitting environmental changes that favor the production of oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; Foyer et al., 1997; May et al., 1998; Foyer and Noctor, 2005). The glutathione/GR system is involved in H2O2 metabolism by reducing dehydroascorbate generated following the (per)oxidation of ascorbate (Asada, 1999). This pathway is one way in which H2O2 reduction could be coupled to NADPH oxidation, with the first reaction catalyzed by ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and the last by GR, although ascorbate regeneration can occur independently of reduced glutathione (GSH) through NAD(P)H-dependent or (in the chloroplast) ferredoxin-dependent reduction of monodehydroascorbate (MDAR; Asada, 1999). Additional complexity of the plant antioxidative system has been highlighted by identification of several other classes of antioxidative peroxidases that could reduce H2O2 to water. These include the TRX fusion protein CDSP32 (Rey et al., 2005) and several types of peroxiredoxin, many of which are themselves TRX dependent (Dietz, 2003). Plants lack animal-type selenocysteine-dependent glutathione peroxidase (GPX), instead containing Cys-dependent GPX (Eshdat et al., 1997; Rodriguez Milla et al., 2003). Despite their annotations as GPX, these enzymes are now thought to use TRX rather than GSH (Iqbal et al., 2006). However, H2O2 could still oxidize GSH via peroxidatic glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and/or glutaredoxin (GRX)-dependent peroxiredoxin (Wagner et al., 2002; Jacquot et al., 2008). Metabolism of H2O2 may occur through APX or through ascorbate-independent GSH peroxidation, both of which potentially depend on GR activity, as well as through TRX-dependent pathways. The relative importance of these pathways remains unclear.

The major sites of intracellular H2O2 production in most photosynthetic plant cells are the chloroplasts and peroxisomes (Noctor et al., 2002). Despite this, Davletova et al. (2005) demonstrated a crucial role for cytosolic APX1 in redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis. This finding implies that the cytosolic ascorbate-glutathione pathway is important in metabolizing H2O2 originating in other organelles, thus marking out this compartment as a key site in which redox signals are integrated to drive appropriate responses. Cytosolic metabolism of H2O2 could be key in setting appropriate conditions for thiol-disulfide regulation through cytosolic/nuclear signal transmitters such as NPR1 and TGA transcription factors (Després et al., 2003; Mou et al., 2003; Rochon et al., 2006; Tada et al., 2008). Because peroxisomal reactions can be a major producer of H2O2, a related issue that remains unresolved is to what extent reductive H2O2 metabolism overlaps with metabolism through catalase, which is confined to peroxisomes and homologous organelles. Intriguingly, double antisense tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) lines in which both catalase and cytosolic APX were down-regulated showed a less marked phenotype than single antisense lines deficient in either enzyme alone (Rizhsky et al., 2002). This observation implies that if the major role of the GR-glutathione system is indeed to support reduction of dehydroascorbate to ascorbate, down-regulation of cytosolic GR capacity should produce a similar effect to APX deficiency.

Two genes are annotated to encode GR in plants. Pea (Pisum sativum) chloroplast GR was the first plastidial protein shown also to be targeted to the mitochondria (Creissen et al., 1995). Dual targeting of this protein also occurs in Arabidopsis (Chew et al., 2003), where the plastidic/mitochondrial isoform is named GR2. The second gene, GR1, is predicted to encode a cytosolic enzyme. In pea, cytosolic GR has been well characterized at the biochemical level (Edwards et al., 1990; Stevens et al., 2000), but the functional significance of the enzyme remains unclear. Underexpression or overexpression studies in tobacco and poplar (Populus species) have reported significant effects of modifying chloroplast GR capacity (Aono et al., 1993; Broadbent et al., 1995; Foyer et al., 1995; Ding et al., 2009). Less evidence is available supporting an important role for cytosolic GR. In insects, GSSG reduction can also be catalyzed by NADPH-TRX reductases (NTRs; Kanzok et al., 2001), and it has recently been shown that Arabidopsis cytosolic NTR can functionally replace GR1 (Marty et al., 2009).

Therefore, key outstanding issues in the study of redox homeostasis and signaling in plants are (1) the importance of GR/glutathione in H2O2 metabolism and/or H2O2 signal transmission and (2) the specificity of GSH and TRX systems in H2O2 responses. In this study, we sought to address these questions by a genetically based approach in which the effects of modified H2O2 and glutathione were first analyzed in parallel in single mutants and then directly through the production of double mutants. This was achieved using gr1 insertion mutants and a catalase-deficient Arabidopsis line, cat2, in which intracellular H2O2 drives the accumulation of GSSG in a conditional manner (Queval et al., 2007). Our study provides in vivo evidence for a specific irreplaceable role for GR1 in H2O2 metabolism and signaling.

RESULTS

Characterization of gr T-DNA Mutants

While T-DNA insertions in the coding sequence of dual-targeted chloroplast/mitochondrial GR2 are embryo lethal (Tzafrir et al., 2004), homozygous gr1 mutants were readily obtained. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR confirmed the absence of GR1 transcript, while total extractable GR activity was decreased by 40% relative to ecotype Columbia (Col-0; Supplemental Fig. S1). Despite these effects, repeated observations over a period of 5 years showed that the mutation produced no difference in rosette growth rates from Col-0 in either short days (SD) or long days (LD) or in flowering timing and leaf number (data not shown). Thus, our analysis is in agreement with the report of Marty et al. (2009) that absence of cytosolic GR activity caused a measurable decrease in leaf GR activity but that this did not cause phenotypic effects.

Comparative Analysis of Glutathione- and H2O2-Dependent Changes in Gene Expression

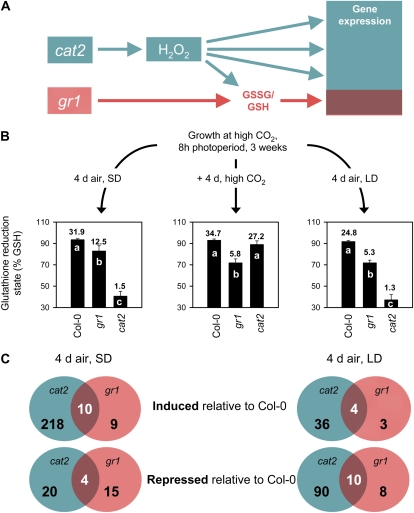

Because gr1 mutants are aphenotypic in typical growth conditions, this study analyzed the potential role of the enzyme in H2O2 metabolism and signaling. First, we performed parallel microarray analysis of GSSG-accumulating gr1 and the catalase-deficient mutant cat2, which conditionally accumulates GSSG triggered by photorespiratory H2O2 production (Queval et al., 2007). To compare effects on transcript abundance while minimizing possible interference of long-term developmental effects due to oxidative stress in cat2 grown from seed in air, plants were sampled following initial growth at high CO2, where the cat2 mutation is silent (Queval et al., 2007). This experimental design was chosen to allow comparison of the effects of modified glutathione status in gr1 with similar H2O2-induced effects triggered in cat2 after transfer from high CO2 to air. Our rationale was that while H2O2 may modify gene expression through a number of signaling mechanisms, any effects mediated via glutathione should also be observed in gr1, even in the absence of the oxidative stress that drives GSSG accumulation in cat2 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Comparison of H2O2- and glutathione-regulated changes in gene expression. A, Scheme depicting experimental strategy. B, Glutathione reduction states (100 GSH/total glutathione) in Col-0, gr1, and cat2 in high CO2 or in air in 8-h (SD) or 16-h (LD) growth photoperiods. Different letters indicate significant difference between genotypes at P < 0.05. The numbers show the GSH to GSSG ratios. Data are means ± se of five to seven independent extracts. C, Overlap in significantly induced or repressed genes in cat2 or gr1 following induction of glutathione oxidation in cat2 after transfer from high CO2 to air. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

As previously reported, cat2 showed a wild-type phenotype at high CO2. The consequences of the cat2 mutation for gene expression and phenotype in air are strongly influenced by growth photoperiod (Queval et al., 2007). Thus, measurements of transcripts and antioxidant were performed after transfer of gr1 and cat2 from high CO2 to air in both SD (8-h photoperiod) and LD (16-h photoperiod). In both photoperiods (and at high CO2), the glutathione reduction state was lower in gr1 than in Col-0 (Fig. 1B). In cat2, however, this factor was only lower than in Col-0 after transfer to air, where it was decreased below the values observed in gr1. In both mutants, leaf ascorbate contents were much less affected than glutathione. The only significant difference was observed in ascorbate reduction state in cat2 in LD (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Analysis of microarray data was performed by considering as being differentially expressed genes with a Bonferroni P ≤ 0.05, as described by Gagnot et al. (2008). An additional selection criterion was introduced by considering only genes that showed statistically significant same-direction change in both biological replicates. The analysis showed that H2O2-regulated gene expression (in cat2) was highly daylength dependent (Fig. 1C). More genes were significantly induced in cat2 transferred to air in SD than in LD, whereas the reverse was true for significantly repressed genes. Fewer genes were affected in gr1, but effects were also daylength conditioned. Of genes induced in gr1 in SD, only three were also induced in LD, together with another four LD-specific genes. The number of repressed genes in gr1 in LD was similar to that in SD (Fig. 1C), but of these, only two were common (Supplemental Table S2). Thus, as for genes regulated by an H2O2 signal, gene expression dependent on a drop in glutathione reduction state was strongly determined by photoperiod context. Of the 58 genes showing significantly modified expression in response to a mild perturbation of glutathione redox state in gr1, most showed significant same-direction changes in at least one cat2 replicate (Supplemental Table S2). It should be noted that Figure 1C provides a conservative estimate of overlap between gr1 and cat2 transcriptomes because only genes that showed statistically significant same-direction changes in all four dye-swap repeats (two gr1/Col-0 and two cat2/Col-0) are considered.

Several genes whose expression was modified in gr1 encoded stress-related proteins, notably cadmium-, salt-, and cold-responsive genes, as well as two GSTs (GSTU7 and GSTU6) and three multidrug resistance-associated proteins (Supplemental Table S2). This is consistent with the roles of glutathione in redox homeostasis, heavy metal resistance, cold acclimation, and metabolite conjugation and transport (Cobbett et al., 1998; May et al., 1998; Kocsy et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2002; Gomez et al., 2004).

Sixteen of the 58 gr1-sensitive genes are annotated as phytohormone associated. In all cases, induction or repression of these genes was dependent on daylength context (Table I). A putative monoxygenase with similarity to salicylic acid (SA)-degrading enzymes was among the induced genes, whereas other differentially expressed genes in gr1 were associated with auxin, gibberellin, abscisic acid, and ethylene function (Table I). The most striking impact of the gr1 mutation was on the expression of genes involved in jasmonic acid (JA) synthesis and signaling. Of the 18 genes repressed in gr1 in LD, eight have been shown to be early JA-responsive genes (Yan et al., 2007). These genes encoded, among others, LIPOXYGENASE3 (LOX3), MYB95, GSTU6, and two of the 12 JASMONATE/ZIM DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins recently characterized as JA-inducible repressors of JA signaling (Staswick, 2008; Browse, 2009). All but one of the JA-dependent genes repressed in gr1 in LD showed the same response in the GSSG-accumulating cat2 mutant (Table I).

Table I. Annotated phytohormone-associated genes showing significantly modified transcript levels in gr1.

| Gene Identifier | Name | 8-h Days | 16-h Days | Hormone |

| At3g50970a | XERO2 | Induced | – | Abscisic acid |

| At4g15760 | MO1 | Induced | – | SA |

| At4g23600a | CORI3 (JR2) | Induced | – | JA |

| At5g05730 | ASA1 | Induced | – | Ethylene |

| At1g74670a | Unknown protein | Repressed | – | GA |

| At5g54490 | PBP1 | Repressed | – | Auxin |

| At5g61590 | ERF B3 member | Repressed | – | Ethylene |

| At5g61600 | ERF B3 member | Repressed | – | Ethylene |

| At1g17420a | LOX3 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At1g74430/40a | MYB95 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At2g24850 | TAT3 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At2g29440a | GSTU6 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At2g34600a | JAZ7 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At2g38240a | 2OGOR | – | Repressed | JA |

| At4g15440a | HPL1 | – | Repressed | JA |

| At5g13220a | JAZ10 | – | Repressed | JA |

Significant same-direction response in cat2 in the same condition.

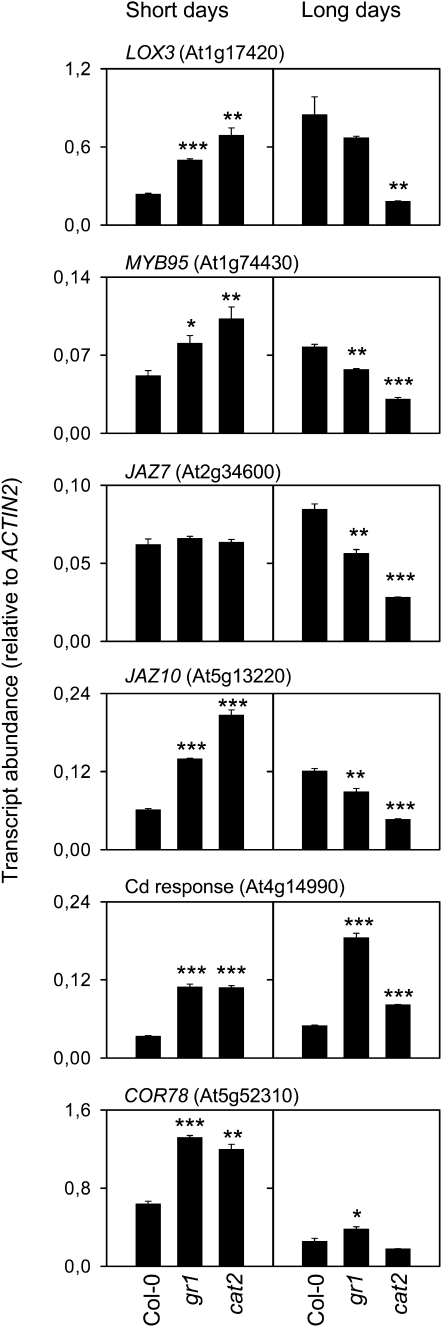

Two induced stress-associated genes and four JA-dependent genes that showed similar responses in gr1 and cat2 were selected for quantitative PCR analysis. This confirmed the induction in gr1 of the cold-regulated COR78 in SD and of the cadmium-responsive At3g14990 in both daylength conditions (Fig. 2). For the JA-associated genes, quantitative PCR revealed that in addition to repression in gr1 and cat2 in LD, three of the four genes (LOX3, MYB95, and JAZ10) were also induced in SD (Fig. 2). Thus, GR1-dependent glutathione status influences the expression of genes involved in JA synthesis and signaling in a daylength-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Verification of selected genes repressed or induced in gr1 by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are means ± se of two independent extracts. * P < 0.1, ** P < 0.05, *** P < 0.01.

Genetic Analysis of GR1 Function in Responses to H2O2

To directly explore the role of GR1 and glutathione status in the H2O2 response, the gr1 mutation was crossed into the cat2 background. Preliminary analysis of F2 seeds grown in air failed to identify double cat2 gr1 homozygotes. Thus, F3 seeds from a cat2/cat2 GR1/gr1 genotype were germinated and grown at high CO2, where, as noted above, the cat2 mutation is phenotypically silent because photorespiratory H2O2 production is largely shut down. Genotyping of these seeds identified several plants with cat2/cat2 gr1/gr1 genotypes, suggesting selection against cat2 gr1 double homozygotes in the presence of photorespiratory H2O2 production (air) but not in its absence (high CO2).

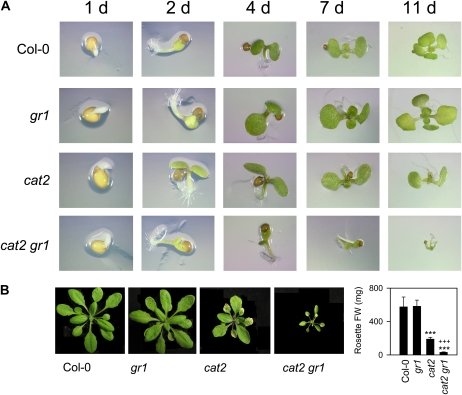

When F4 seeds obtained from F3 cat2 gr1 double homozygotes identified at high CO2 were sown on agar plates in air, germination was similar to Col-0, gr1, and cat2, but growth was severely compromised in all cat2 gr1 plants from the cotyledon stage onward (Fig. 3A). Although cat2 gr1 was able to grow on soil at moderate irradiance, all plants with this genotype showed a dwarf rosette phenotype that was much more severe than that observed in cat2 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Germination and growth phenotype of cat2 gr1 double mutants. A, Germination and growth on agar. B, Plants grown on soil from germination in a 16-h/8-h day/night regime. Asterisks indicate significant differences between mutants and Col-0, while pluses indicate significant differences between cat2 and cat2 gr1. FW, Fresh weight. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

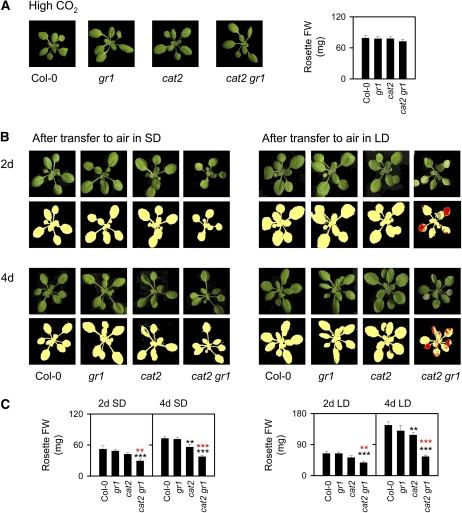

The cat2 gr1 phenotype was completely reverted by growth at high CO2 (Fig. 4A). Together with the aphenotypic nature of the single gr1 mutant, this observation indicates that the functional importance of GR1 is highly correlated with conditions of increased intracellular H2O2 availability. To further investigate this point, we analyzed the phenotypic responses of cat2 gr1 grown at high CO2 after transfer to air in either SD or LD. Lesions developed in cat2 at 5 to 6 d after transfer to LD but did not develop in SD (data not shown). Four days after the transfer to LD, few or no lesions were apparent on cat2 leaves (Fig. 4B). By contrast, extensive bleaching was observed on cat2 gr1 leaves as early as 2 d after the transfer to air in LD (Fig. 4B). In both photoperiods, photorespiratory H2O2 induced slower growth in cat2, and this effect was exacerbated by the absence of GR1 function (Fig. 4C). Remarkably, however, bleaching was limited or absent in cat2 gr1 transferred to air in SD.

Figure 4.

Rescue of a wild-type phenotype in cat2 gr1 at high CO2, and rapid daylength-dependent induction of leaf bleaching following transfer to air. A, Plants were germinated and grown for 25 d at high CO2 (3,000 μL L−1). FW, Fresh weight. B, Plants transferred from high CO2 to air in either SD or LD conditions. False-color imaging of lesions (red) are shown under each photograph. C, Rosette fresh weights of plants transferred to air in either SD or LD. Histograms show means ± se of at least six plants. Black asterisks indicate significant differences between mutant and Col-0, and red asterisks indicate significant differences between cat2 and cat2 gr1: ** P < 0.05, *** P < 0.01.

To verify the conditional genetic interaction between the cat2 and gr1 mutations, a second allelic gr1 T-DNA line was obtained and crossed with cat2. F2 plants from this cross were grown at high CO2 and then transferred to air in LD, and lesions were quantified and plants were genotyped (Supplemental Fig. S3). Neither F1 CAT2/cat2 GR1/gr1 double heterozygotes grown in air nor any F2 plants grown at high CO2 showed any apparent phenotype (data not shown). Of 93 F2 plants transferred from high CO2 to air in LD, seven displayed readily visible lesions within 4 d (Supplemental Fig. S3). Genotyping confirmed that all plants showing substantial lesions were cat2/cat2 gr1/gr1 double homozygotes, and lesion quantification and rosette fresh mass distinguished these plants from the eight other genotypes (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Microarray Analysis of the H2O2-GR1 Interaction

To identify H2O2-regulated genes whose expression is dependent on GR1, transcript profiling of cat2 and cat2 gr1 was performed after transfer of plants grown at high CO2 to air. In view of the above phenotypic observations and the daylength-dependent transcript profiles for cat2 and gr1 single mutants (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S2), the analysis was performed after transfer to both SD and LD. A full list of significantly different genes and signal intensities is given in Supplemental Table S3.

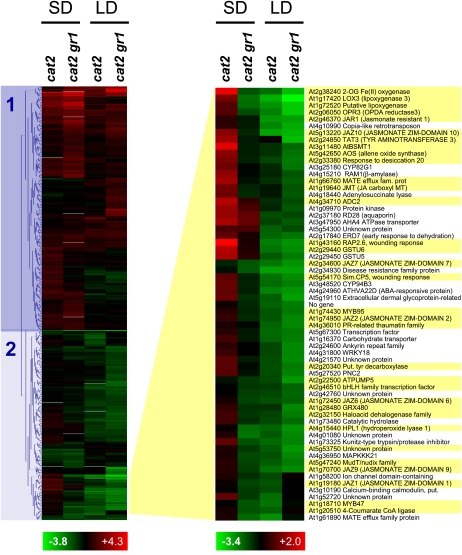

Clustering analysis of significantly different transcripts delineated two major patterns of H2O2-induced gene expression (Fig. 5). The first was largely composed of genes that were induced by photorespiratory H2O2 in cat2 and cat2 gr1 (cluster 1), while the second comprised genes that responded in a daylength-dependent manner (cluster 2). The most striking impact of the gr1 mutation in the cat2 background was to annul or impair the induction of genes by photorespiratory H2O2 in SD, an effect exemplified by a subcluster of genes in cluster 2. Of 62 genes in this subcluster, 33 are annotated as involved in JA- or wounding-dependent responses (Taki et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2007; http://www.arabidopsis.org) and are highlighted yellow in Figure 5. Data mining of all significantly different genes using the above data sets revealed that, in all, 47 genes inducible by JA or wounding, or encoding proteins involved in JA synthesis, conjugation, or signaling, were differentially expressed in cat2 and/or cat2 gr1 (Supplemental Table S4). Twenty-five of these were among 35 genes recently shown to be induced by wounding in a JA-dependent manner (Yan et al., 2007), while among the others were established JA-associated genes such as LOX2, LOX3, OPR3, JAZ1, JAZ3, JAZ7, JAZ9, JAR1, and JMT1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of gene expression in cat2 and cat2 gr1 following transfer from high CO2 to air in either 8-h (SD) or 16-h (LD) growth conditions. Hierarchical clustering was performed using MultiExperimentViewer software. The exploded heat map at the right shows a subcluster of 62 genes that includes 33 JA- or wounding-associated genes (highlighted yellow).

In the cat2 single mutant, the predominant effect of H2O2 on genes involved in JA synthesis and signaling was induction in SD and/or repression in LD. This daylength-dependent regulation was strongly modulated by the absence of GR1 function in cat2 gr1. Of the 47 JA-associated transcripts whose abundance was significantly modified in cat2 and/or cat2 gr1 relative to Col-0, only 10 did not show differential expression between the two lines in at least one photoperiod (Supplemental Table S4). The overwhelmingly predominant effect of the gr1 mutation in the cat2 background was to cause or enhance repression (e.g. LOX2, JMT1, JAZ3), to oppose induction in SD (e.g. RAP2.6, JAZ10, AOS), or both (LOX3, TAT3, OPR3).

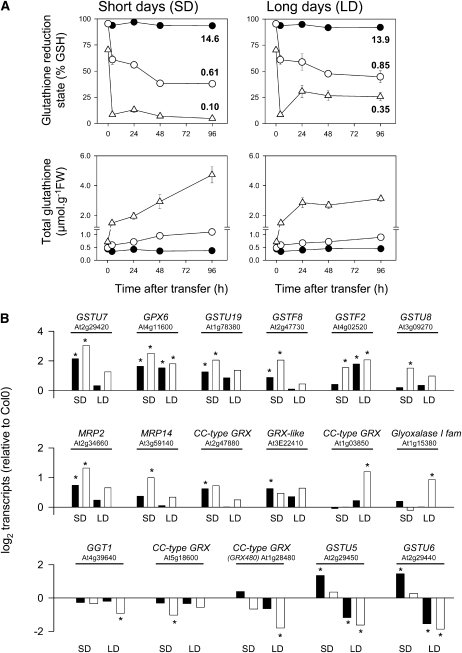

Profiling of Glutathione and Associated Gene Expression in cat2 gr1

Consistent with the absence of phenotype at high CO2 (Fig. 4A), cat2 glutathione status was similar to the wild type (95% GSH), whereas in cat2 gr1 the glutathione pool was only about 70% reduced (i.e. similar to the gr1 single mutant in air or at high CO2; Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S2). These observations are consistent with the silent nature of the cat2 mutation at high CO2 and with a constitutive oxidation of glutathione in the gr1 genotype. The impact of the gr1 mutation on glutathione in conditions of increased H2O2 was assessed under the same conditions as for the microarray analysis. A time course following transfer to air revealed that leaf glutathione (1) became progressively oxidized and accumulated in cat2; (2) became much more rapidly oxidized and accumulated more strongly in cat2 gr1; and (3) was most oxidized and most strongly accumulated in cat2 gr1 in SD. The changes in glutathione involved a fall in the GSH to GSSG ratio to below 1 in cat2 and cat2 gr1, with the lowest ratio observed in cat2 gr1 in SD (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Glutathione contents and glutathione-related gene expression in cat2 and the cat2 gr1 double mutant. A, Time course of changes in percentage glutathione reduction and total glutathione in the different lines following transfer from high CO2 to air. Black circles, Col-0; white circles, cat2; white triangles, cat2 gr1. Top, 100 × GSH/total glutathione (the numbers indicate GSH to GSSG ratio for the final time points). Bottom, total glutathione (GSH + 2 GSSG). Error bars that are not apparent are contained within the symbols. FW, Fresh weight. B, Expression values of significantly different glutathione metabolism transcripts in cat2 and cat2 gr1 relative to Col-0. Black bars, cat2; white bars, cat2 gr1. The top two panels show genes that were induced, while the bottom panel shows genes that were significantly repressed in at least one sample type.

Mining of the transcriptome data for glutathione-associated genes showed that modified glutathione status in cat2 and cat2 gr1 was associated with the induction of genes encoding three GSTs of the tau class (GSTU7, GSTU8, GSTU19) and two of the phi class (GSTF2, GSTF8), two multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP2, MRP14), a glutathione/thioredoxin peroxidase (GPX6), a glyoxylase I family protein, two members of the GRX family, and a GRX-like expressed protein (Fig. 6B). These genes were equally or more strongly induced in cat2 gr1 compared with cat2, although the effect depended on daylength. In no case did the gr1 mutation oppose induction of these genes in cat2, which were all found to be grouped in cluster 1 on the heat map shown in Figure 5.

Five glutathione-associated genes showed a different expression pattern (Fig. 6B, bottom) and were all found within cluster 2 shown in Figure 5. While one GRX (At5g18600) showed a tendency to repression in all conditions, repression was only significant in cat2 gr1 in SD. GSTU5 and GSTU6 were both induced in cat2 but not in cat2 gr1 in SD and were repressed in both genotypes in LD (Fig. 6B). The gr1 mutation in the cat2 background also produced repression of GGT1 and GRX480, specifically in LD. Thus, the expression patterns of these five genes were similar to those of JA-dependent genes (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S4). In contrast to the differential expression of these glutathione-dependent genes, the expression of cytosolic TRXs and associated genes involved in thiol-disulfide exchange reactions was little or not affected in either the cat2 or cat2 gr1 genotype (Supplemental Table S5).

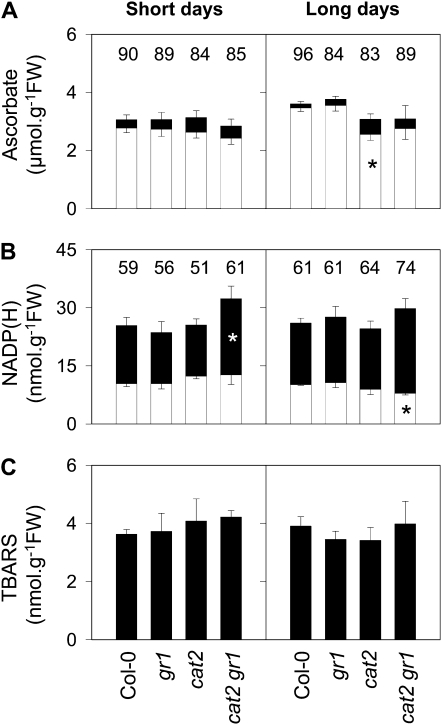

Analysis of Oxidative Stress and the Ascorbate-Glutathione Pathway

Catalase-independent pathways of H2O2 metabolism depend on ascorbate, which is considered to be partly regenerated by glutathione, while NADPH is required for reduction of GSSG. Despite this, the effects of gr1 and cat2 mutations on glutathione pools were not associated with marked perturbation of leaf ascorbate pools, which remained more than 80% reduced in all plants. In LD conditions, ascorbate was decreased in cat2 and cat2 gr1, although this small effect was only statistically significant for cat2 (Fig. 7A). Like ascorbate, the NADP reduction state was not greatly affected in any of the samples (Fig. 7B). The only significant effects were observed in cat2 gr1, which in SD had more NADPH than Col-0 and in LD less NADP+. Because of these effects, the most reduced NADP(H) pools were observed in cat2 gr1. Assay of lipid peroxidation products using thiobarbituric acid also showed no significant effect between any of the samples in either condition (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Leaf ascorbate, NADP(H), and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) in the four genotypes placed in SD (left) and LD (right) in air following growth at high CO2. A, Ascorbate (white bars) and dehydroascorbate (black bars). B, NADP+ (white bars) and NADPH (black bars). C, TBARS. For A and B, numbers above each bar indicate percentage reduction states [100 ascorbate/(ascorbate + dehydroascorbate) in A and 100 NADPH/(NADP+ + NADPH) in B]. Samples were taken 4 d after transfer to air. All data are means ± se of three independent leaf extracts. Asterisks within blocks indicate significant differences from Col-0 values in the same condition: * P < 0.1. FW, Fresh weight.

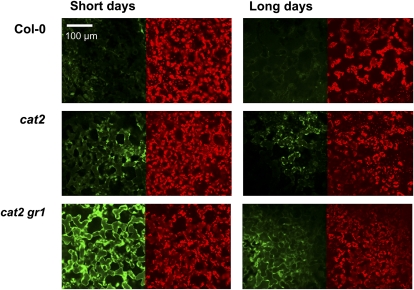

Potential problems that must be taken into account in measuring H2O2 include low assay specificity, interference, and extraction efficiency (Wardman, 2007; Queval et al., 2008). In this study, we used three different techniques to assess H2O2 or reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in cat2 and cat2 gr1. In situ staining using 3,39-diaminobenzidine did not produce evidence for generalized accumulation of H2O2 in gr1, cat2, or cat2 gr1 leaves in SD or LD (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Likewise, assays of extractable peroxides using luminol chemiluminescence did not find increased contents in cat2 or cat2 gr1 in either daylength condition (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Semiquantitative ROS visualization within the mesophyll cells in vivo also revealed that the cat2 mutation caused only minor increases in dichlorofluorescein fluorescence (Fig. 8). The cat2 gr1 double mutant showed an appreciably stronger fluorescence signal, but this effect was specific to plants in SD (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

In vivo visualization of ROS using dichlorofluorescein fluorescence. Leaf mesophyll cells of plants grown at high CO2 and then transferred to air for 4 d in SD or LD were imaged in intact tissue by confocal microscopy. Each pair of images shows the same area measured for green dichlorofluorescein fluorescence (left) and red chlorophyll autofluorescence (right). Representative examples from three independent experiments are shown. Magnification was the same for all samples. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

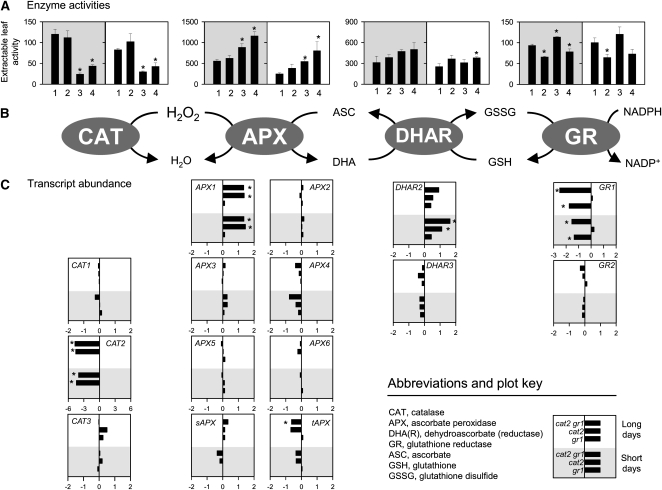

To further assess the impact of the mutations on the ROS-antioxidant interaction, we measured the extractable activities and expression of APX, catalase, GR, and dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), the enzyme linking glutathione and ascorbate pools. The only one of these enzyme activities that was significantly different between Col-0 and gr1 was GR (Fig. 9A). Similarly, the gr1 mutation in the Col-0 background produced no significant change in transcripts other than GR1 (Fig. 9C). Decreased catalase activity in cat2 was associated with an increase in APX activity in both conditions (Fig. 9A). Increased APX activity was accompanied by induction of transcripts for APX1, encoding the cytosolic isoform (Davletova et al., 2005). Of eight APX transcripts present on the chip, only APX1 was significantly increased in cat2, and as for APX activity, this effect was similar in both SD and LD (Fig. 9C). Induction of APX1 in cat2 was accompanied by induction of a cytosolic DHAR (DHAR2), although this effect was stronger in SD than in LD and was not associated with a marked increase in the overall activity of this enzyme. Compared with Col-0, effects in cat2 gr1 were similar to those observed in cat2 (i.e. induction of APX1 in both SD and LD, an increase in extractable APX in the two conditions, and induction of DHAR2 transcripts, particularly in SD; Fig. 9). Overall, the presence of the gr1 mutation in Col-0 or cat2 backgrounds did not greatly affect the responses of these antioxidative systems relative to the respective controls. Despite the oxidation of the glutathione pool in cat2 and its very marked oxidation in cat2 gr1 (Fig. 6A), neither genotype showed compensatory induction of GR2 transcripts, encoding the chloroplast/mitochondrial isoform (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

Major antioxidative enzyme activities and transcript levels in Col-0, gr1, cat2, and cat2 gr1 after transfer to air in SD (gray backgrounds) or LD (white backgrounds). A, Enzyme activities. The x axis numbers refer to Col-0 (1), gr1 (2), cat2 (3), and cat2 gr1 (4). Units are μmol mg−1 protein min−1 (catalase) and nmol mg−1 protein min−1 (other enzymes), and values are means of three independent extracts. Asterisks indicate significant differences from Col-0 at P < 0.05. B, Simplified scheme of catalase- and ascorbate-dependent H2O2 metabolism. C, Abundance (log2 scale, relative to Col-0) of corresponding transcripts for which probes were present on the CATMA array. Asterisks indicate transcripts that showed significant same-direction differences from controls in both biological replicates. Where no bar is apparent, transcripts were almost identical in abundance in the mutant and the corresponding Col-0 control.

SA Signaling and Pathogen Reponses

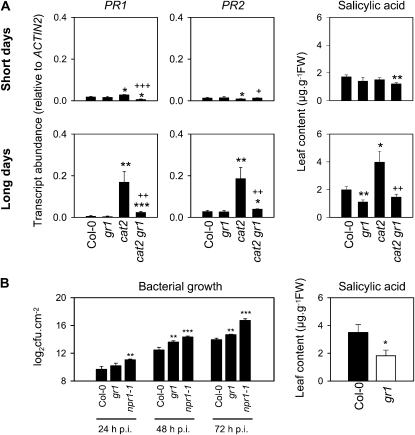

Given the observed effects on JA-associated genes (Fig. 5; Table I; Supplemental Table S4) and the opposition between JA signaling and SA-dependent pathways (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Koorneef et al., 2008), we analyzed SA and expression of SA marker genes in gr1, cat2, and cat2 gr1 in both daylength conditions. SA-dependent PR genes (PR1, PR2) were both significantly induced in cat2 in LD but less strongly or not at all in SD (Fig. 10A). Induction of SA-dependent PR genes in cat2 in LD was antagonized by the gr1 mutation, producing significantly lower expression in cat2 gr1. Leaf SA contents were similar in all samples in SD, although slightly decreased in cat2 gr1, whereas in LD H2O2-induced accumulation was observed in cat2 but not in cat2 gr1 (Fig. 10A). The gr1 mutation also decreased basal SA levels in the Col-0 background in LD (Fig. 10A).

Figure 10.

Pathogen-associated responses in GR-deficient lines. A, PR gene expression and SA contents in Col-0, gr1, cat2, and cat2 gr1 in two photoperiods after transfer from high CO2 to air. Top, 8-h days; bottom, 16-h days. Data are means ±se of two to three biological samples. FW, Fresh weight. B, Bacterial resistance and SA contents in Col-0 and gr1 grown under standard conditions in air. Asterisks indicate significant differences between mutants and Col-0 (* P < 0.1, ** P < 0.05, *** P < 0.01), while pluses indicate significant differences between cat2 and cat2 gr1 (+ P < 0.1, ++ P < 0.05, +++ P < 0.01).

We investigated the response of gr1 to infection with the virulent bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato strain DC3000 (Fig. 10B). Bacterial growth in gr1 leaves was intermediate between that observed in Col-0 and the npr1-1 mutant, in which cytosolic redox-modulated NPR1 function is lacking (Mou et al., 2003). In agreement with the data of Figure 10A, increased sensitivity to bacteria in gr1 was associated with lower total SA levels than in Col-0 (Fig. 10B).

DISCUSSION

Recent data have highlighted the functional overlap between glutathione and TRX systems (Reichheld et al., 2007; Marty et al., 2009). A key question, therefore, concerns the specificity of cytosolic GR-glutathione and NTR-TRX functions. Glutathione has been proposed to play a role in H2O2 signaling (Foyer et al., 1997; May et al., 1998). Here, we present a targeted, genetically based study of such a role by using cat2 and gr1 mutants in combination.

GR1 Plays a Nonredundant Role in H2O2 Metabolism and Signaling

In this study, the cat2 mutant was used both as a reference GSSG-accumulating H2O2 signaling system and as a genetic background in which to directly explore the GR1-H2O2 interaction. Because daylength-dependent effects have been described for redox signaling during pathogen and oxidative stress responses (Dietrich et al., 1994; Karpinski et al., 2003; Queval et al., 2007; Vollsnes et al., 2009), we analyzed the importance of GR1 in Col-0 and cat2 backgrounds in two growth daylengths.

Our analysis of gr1 in the Col-0 background confirm the results of Marty et al. (2009) that GR1 is not required for growth in optimal conditions. However, GR1 plays an important role when intracellular H2O2 production is increased and during pathogen challenge. The effect of gr1 on the cat2 phenotype contrasts with results in which plants were exposed to exogenous H2O2 present in agar, where no difference was found between gr1 and Col-0 phenotypes, even at highly challenging H2O2 concentrations (Marty et al., 2009). This suggests that the site of H2O2 production is crucial. Enhanced H2O2 availability in cat2 leaves placed in air occurs intracellularly through the photorespiratory enzyme, glycolate oxidase, which is located in peroxisomes. In these conditions, redox perturbation in cat2 produces similar effects to those observed in stress conditions, notably oxidation and accumulation of glutathione and changes in the abundance of many stress-related transcripts. GR activity has been detected in pea leaf peroxisomes, and it is likely that GR1 is found in Arabidopsis peroxisomes as well as in the cytosol (Jiménez et al., 1997; Kaur et al., 2009). Therefore, it is possible that GR1 is important in peroxisomal ascorbate- and/or glutathione-dependent H2O2 metabolism. At least one (APX3) and possibly as many as three (APX3, APX4, APX5) Arabidopsis APXs are targeted to peroxisomes or the peroxisomal membrane (Narendra et al., 2006), but the corresponding transcripts were not significantly induced in gr1, cat2, or cat2 gr1 (Fig. 9). Most of the antioxidative genes that were induced in cat2 and cat2 gr1 encoded cytosolic enzymes, including APX1, DHAR2, and MDAR2 (Supplemental Table S3). Our analysis thus points to tight coupling between H2O2 produced in the peroxisomes and cytosolic antioxidative systems.

The dramatic accumulation of GSSG in cat2 gr1 placed in air shows that GSH regeneration through alternative pathways is rapidly exceeded under conditions of enhanced intracellular H2O2 availability. To our knowledge, the accumulation of GSSG in cat2 gr1 (up to 2 μmol g−1 fresh weight; Fig. 6A) exceeds previously reported values for this compound in leaf tissues. Further work is required to identify the compartments in which such marked accumulation of GSSG occurs. Analyses of the gr1 single mutant in air and the cat2 gr1 double mutant at high CO2 show that mild perturbation of the glutathione pool is not sufficient to produce marked phenotypic effects, while effects produced by the more severe perturbation of glutathione in cat2 gr1 in air were dependent on growth daylength. Lesions were not observed in cat2 gr1 in SD, even though these plants showed the most dramatic GSSG accumulation and the lowest GSH to GSSG ratios. Oxidized glutathione pools are considered to be among the cellular factors underlying dormancy and cell death (Kranner et al., 2002, 2006). However, our data show that although growth arrest was linked to glutathione perturbation in both daylengths, leaf cells can tolerate extreme perturbation of intracellular thiol-disulfide state without undergoing bleaching (Fig. 5). Analysis of ascorbate, thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, and ROS also provided little evidence that oxidative stress was stronger in LD compared with SD.

The dramatic perturbation of glutathione pools in cat2 gr1 compared with cat2 provides direct evidence for the role of GR1 in intracellular H2O2 metabolism. Analysis of ROS suggests that H2O2 accumulation in cat2 is localized and/or minimized by metabolism through ascorbate- and/or glutathione-dependent pathways. Little or no detectable increase in H2O2 in cat2 compared with the wild type is consistent with previous studies of catalase-deficient tobacco and barley (Hordeum vulgare) lines (Willekens et al., 1997; Noctor et al., 2002; Rizhsky et al., 2002). Although certain antioxidative enzymes and transcripts were up-regulated in cat2 and cat2 gr1, these effects were at least as marked in SD as in LD. ROS signal intensity was increased in cat2 gr1 in SD, but increases were less evident in this genotype in LD (Fig. 8), conditions in which bleaching occurred (Fig. 5). One explanation of the requirement of LD conditions for leaf bleaching is that other daylength-linked signals are required in addition to oxidative stress intensity.

The phenotype of cat2 gr1 in LD contrasts with observations of tobacco plants deficient in both cytosolic APX and catalase, which showed an ameliorated phenotype compared with parent lines (Rizhsky et al., 2002). One explanation of the different effects of GR and APX deficiency in catalase-deficient plants is that some proportion of H2O2 is metabolized through GR-dependent but ascorbate-independent pathways. Hence, as well as GSH oxidation by dehydroascorbate, glutathione perturbation in cat2 may occur through enzyme-catalyzed peroxidation of GSH (e.g. catalyzed by certain GSTs, as discussed further below). Although increases in APX activities in cat2 and cat2 gr1 were associated with induction of APX1 (Fig. 9), several glutathione-associated genes with potential peroxidative functions were also induced in these lines (Fig. 6).

H2O2 and Glutathione Modulate the Expression of Specific Glutathione-Associated Genes in a Daylength-Dependent Manner

Although there was no evidence of oxidative stress or phenotypic effects in the gr1 single mutant, transcriptomes in this line partly overlapped with that of the H2O2 signaling reference system, cat2. Both transcriptomes were found to be highly dependent on daylength. This observation suggests that modulation of redox-linked gene expression by growth daylength is not restricted to oxidative stress or is a secondary consequence of stress-induced phenotypes.

Fewer genes were affected in gr1 than in cat2. Genes affected in cat2 but not gr1 could reflect H2O2 signaling that occurs independently of changes in glutathione (Fig. 1A). The difference could also be related to the stronger perturbation of the glutathione pool in cat2 (Fig. 1B). If the difference can be partly explained by weaker changes in glutathione in gr1, then the overlap in transcriptomes we report could provide a minimum estimate of the importance of glutathione in H2O2 signaling

Many TRX-linked components play roles in oxidative stress (Dietz, 2003; Rey et al., 2005; Pérez-Ruiz et al., 2006), but none of these transcripts was induced by increased H2O2 availability in cat2 or cat2 gr1. A lack of response was also observed for chloroplast ferredoxin-TRX reductase subunit genes and for the two cytosolic NTRs and cytosolic TRXs (Supplemental Table S5). The only TRX-linked gene that was significantly induced by H2O2 was GPX6, and this effect was largely independent of both daylength and the gr1 mutation (Fig. 6).

In contrast to the lack of response of TRX systems, H2O2- or gr1-driven perturbation of glutathione triggered changes in the abundance of transcripts of several glutathione-associated genes, notably GSTs and GRXs. Analysis of GST functions is complicated by the number of genes in plants, notably due to the presence of large plant-specific phi and tau subclasses, as well as substrate overlap between the different enzymes. Our transcript profiling analysis showed that H2O2 modified transcript levels for two phi class (GSTF2, GSTF8) and three tau class (GSTU7, GSTU8, GSTU19) enzymes and that in all cases, these effects were further modulated by daylength and/or the gr1 mutation. Type F GSTs exhibit both conjugase and peroxidase activities, with GSTF8 showing considerable activity against cumene hydroperoxide (Wagner et al., 2002; Dixon et al., 2009). As well as GSTFs, some GSTUs, including GSTU8, show quite high peroxidase activity (Dixon et al., 2009).

Analysis of GRX function is also complicated by the number of genes, notably due to a large subclass that is specific to higher plants. At least 30 GRX genes have been described in Arabidopsis (Lemaire, 2004; Meyer et al., 2008). Based on active-site sequences, these are subclassified into CPYC, monothiol CGFS, and CC-type GRX, with the last subclass being specific to land plants (Lemaire, 2004). Although at least one CGFS GRX is implicated in oxidative stress (Cheng et al., 2006), no CPYC or CGFS GRXs showed differential expression in gr1, cat2, or cat2 gr1 in either photoperiod condition (Supplemental Table S5). All differentially expressed GRX genes observed in our analysis belong to the CC-type subclass, consisting of 20 identified members that are thought to encode cytosolic proteins. The functions of most CC-type GRXs remain obscure, but two have been implicated in the regulation of gene expression by interacting with TGA transcription factors. GRX480 overexpression represses the JA marker gene, PDF1.2, while ROXY1 is required for petal development (Ndamukong et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009). The predicted protein encoded by the GRX-like sequence (Fig. 6B) has an active-site CCMS motif that is shared with nine annotated GRX proteins, and BLAST analysis revealed that the protein has 58% to 60% amino acid identity with five of these CCMS GRXs. The H2O2- and/or gr1-dependent changes in CC-type GRXs suggest that the encoded proteins may play roles in the redox regulation of gene expression.

GR1 Is Required for SA Responses and for Expression of Genes Involved in JA Signaling

The cat2 mutation causes accumulation of SA and induction of SA responses in LD but not SD (Fig. 10). GR1 function appears to be required for optimal SA production, as this was compromised in the gr1 single mutant relative to Col-0 and in cat2 gr1 relative to cat2 (Fig. 10). Furthermore, gr1 showed decreased resistance to bacteria, while induction of PR genes in cat2 gr1 was compromised compared with cat2. As well as effects on SA production itself, the gr1 mutation could interfere with SA-dependent gene expression by altered redox regulation of NPR1 (Mou et al., 2003; Tada et al., 2008). Because loss of GR1 function in an H2O2 signaling context produces accelerated lesion formation, the enzyme appears to be required both to restrict leaf bleaching and to enable the induction of SA and PR genes.

Several antioxidative genes can be induced by JA, including genes encoding enzymes of glutathione synthesis (Xiang and Oliver, 1998; Sasaki-Sekimoto et al., 2005). Recent reports implicate glutathione-associated components in JA signaling (Ndamukong et al., 2007; Koorneef et al., 2008; Tamaoki et al., 2008). In both Col-0 and cat2 backgrounds, the gr1 mutation affected a suite of JA-associated genes in a daylength-dependent manner. We observed induction of JA genes in cat2 and gr1 single mutants in SD but repression in all mutant genotypes in LD. This may indicate (1) an optimum glutathione redox status for induction of JA genes and (2) daylength-dependent signals that operate to modulate the impact of changes in glutathione status on JA signaling. The daylength- and gr1-modulated expression of several GRX and GSTs suggests that these components may functionally link glutathione and JA signaling. Such components could include GRX480 (Ndamukong et al., 2007), GSTU8-dependent formation of glutathione-oxylipin conjugates (Mueller et al., 2008), and GSTU6, which is among the JA-dependent genes that are rapidly induced by wounding (Yan et al., 2007). In our analysis, similar expression patterns were observed for these glutathione-associated genes and for a suite of JA-dependent genes. Other genes that link glutathione and JA may include GSTU7, GSTU19, and MRP2, which were induced most strongly in cat2 gr1 in SD and less strongly in cat2 and cat2 gr1 in LD. These genes are up-regulated by phytoprostane or 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid treatment (Mueller et al., 2008). Several of the glutathione-associated genes shown in Figure 6 are rapidly induced by methyl jasmonate, 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, phytoprostane, or wounding (Supplemental Fig. S6). Based on JA- or oxylipin-dependent expression patterns, the activities of GSTs against electrophilic metabolites, and interactions of CC-type GRX with transcription factors (Wagner et al., 2002; Ndamukong et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2007; Mueller et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009), it is possible that several GSTs and CC-type GRX could be involved in linking glutathione to JA signaling.

Interestingly, the glutathione-deficient pad2 mutant is compromised in insect resistance (Schlaeppi et al., 2008). Glutathione status is modulated by various stresses, notably biotic challenge, while sulfur deficiency, which can induce JA synthesis genes (Hirai et al., 2003), is an important determinant of glutathione concentration. As well as the influence of glutathione status, our data also underline the potential importance of daylength context in modulating redox-triggered signaling through the JA pathway.

CONCLUSION

While TRX- and glutathione-dependent pathways have overlapping functions in plants (Reichheld et al., 2007; Marty et al., 2009), this study shows that GR1 plays specific roles in intracellular H2O2 metabolism, in daylength-linked control of phytohormone gene expression, and in certain responses to biotic stress. The transcriptomic patterns we report also point to glutathione- and TRX-specific pathways in redox signaling, with relatively little cross talk between the two pathways at the level of gene expression.

Two nonexclusive hypotheses could explain how the GR-glutathione system influences H2O2-linked gene expression. In the first, glutathione turnover would influence H2O2 concentration through its antioxidative function. Most of our observations do not suggest that this is the main cause of the gr1-linked changes in gene expression, although in situ visualization of ROS suggests that it could contribute to differences between cat2 and cat2 gr1, particularly in SD. In the second hypothesis, glutathione status would be a key part of H2O2-triggered signal transduction. This hypothesis receives support from several of our observations, notably the partial overlap between cat2 and gr1 transcriptomes, but further work is required to confirm the role of glutathione status per se.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutant lines carrying T-DNA insertions in the GR1 gene (At3g24170) were identified using insertion mutant information obtained from the SIGnAL Web site (http://signal.salk.edu), and seeds were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (http://nasc.nott.ac.uk). The default gr1 line was gr1-2 (SALK_060425). A second gr1 insertion mutant (SALK_105794), named gr1-1 by Marty et al. (2009), was used to confirm the phenotypic effects of the cat2 gr1 interaction. After identification of homozygotes, all further analyses were performed on plants grown from T3 seeds. The cat2 line was cat2-2 (Queval et al., 2007), now renamed cat2-1.

Identification of Homozygous gr1 Insertion Mutants

Leaf DNA was amplified by PCR (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, 1 min at 72°C, 30 cycles) using primers specific for left T-DNA borders and the GR1 gene (Supplemental Table S1). Fragments obtained were sequenced to confirm the insertion site. Zygosity was analyzed by PCR amplification of leaf DNA, and RT-PCR analysis of GR1 transcripts was performed using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1).

Plant Growth and Sampling

Seeds were incubated for 2 d at 4°C and then sown either on agar or in soil in 7-cm pots. Plants were grown in a controlled-environment growth chamber at the specified photoperiod and an irradiance of 200 μmol m−2 s−1 at leaf level, 20°C/18°C, 65% humidity, and given nutrient solution twice per week. The CO2 concentration was maintained at 400 μL L−1 (air) or 3,000 μL L−1 (high CO2). Samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. Unless otherwise stated, data are means ± se of three independent samples from different plants, and significant differences are expressed using t test at P < 0.1, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01.

Pathogen Tests

The virulent Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato strain DC3000 was used for resistance tests in a medium titer of 5 × 105 colony-forming units mL−1. Whole leaves of 3-week-old plants grown in a 16-h photoperiod were infiltrated using a 1-mL syringe without a needle. Leaf discs of 0.5 cm2 were harvested from inoculated leaves at the appropriate time points. For each time point, four samples were made by pooling two leaf discs from different treated plants. Bacterial growth was assessed by homogenizing leaf discs in 400 μL of water, plating appropriate dilutions on solid King B medium containing rifampicin and kanamycin, and quantifying colony numbers after 3 d.

Microarray Analysis

Microarray analysis was performed using the CATMA arrays containing 24,576 gene-specific tags corresponding to 22,089 genes from Arabidopsis (Crowe et al., 2003; Hilson et al., 2004) plus 1,217 probes for microRNA genes and putative small RNA precursors (information available at http://urgv.evry.inra.fr/projects/FLAGdb++). This array resource has been used in 40 publications over the last 5 years using a protocol based on technical repeats of two independent biological replicates produced from pooled material from independent plants (Achard et al., 2008; Besson-Bard et al., 2009; Krinke et al., 2009), and this approach was adopted in this study. For each biological repeat and each point, RNA samples were obtained by pooling leaf material from independent sets, each of two plants. Samples of approximately 200 mg fresh weight were collected from plants after 3.5 weeks of growth in the conditions specified above. Total RNA was extracted using Nucleospin RNAII kits (Macherey-Nagel) according to the supplier's instructions. For each comparison, one technical replication with fluorochrome reversal was performed for each biological replicate (i.e. four hybridizations per comparison). The labeling of complementary RNAs with Cy3-dUTP or Cy5-dUTP (Perkin-Elmer-NEN Life Science Products), the hybridization to the slides, and the scanning were performed as described by Lurin et al. (2004).

Statistical Analysis of Microarray Data

Experiments were designed with the statistics group of the Unité de Recherche en Génomique Végétale. Normalization and statistical analysis were based on two dye swaps (i.e. four arrays, each containing 24,576 GSTs and 384 controls) as described by Gagnot et al. (2008). To determine differentially expressed genes, we performed a paired t test on the log ratios, assuming that the variance of the log ratios was the same for all genes. Spots displaying extreme variance (too small or too large) were excluded. The raw P values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method, which controls the family-wise error rate (with a type I error equal to 5%) in order to keep a strong control of the false positives in a multiple comparison context (Ge et al., 2003). We considered as being differentially expressed the genes with a Bonferroni P ≤ 0.05, as described by Gagnot et al. (2008). Only genes that showed same-direction statistically significant change in both biological replicates of at least one sample type were considered as statistically significant.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

RNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA plant kit (Macherey-Nagel) and reverse transcribed with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). ACTIN2 transcripts were measured as a control. cDNAs were amplified using the conditions described above for analysis of genomic DNA except that the number of cycles was 50. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed according to Queval et al. (2007). Gene-specific primers are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Enzyme Assays, Metabolite, and ROS Analysis

Extractable enzyme activities were measured as described previously (Veljovic-Jovanovic et al., 2001). Oxidized and reduced forms of glutathione, ascorbate, and NADP were measured by plate-reader assay as described by Queval and Noctor (2007). SA was measured according to the protocol of Langlois-Meurinne et al. (2005). Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances were assayed and calculated as described by Yang et al. (2009). In situ visualization of ROS was performed using dichlorodihydrofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH2-DA) by a protocol modified from Oracz et al. (2009). Leaves were vacuum infiltrated twice for 15 min at room temperature with DCFH2-DA, carefully rinsed, and kept in the dark. DCF fluorescence at 510 to 550 nm was visualized on a confocal microscope, simultaneously with red chlorophyll autofluorescence, using argon laser excitation at 488 nm.

Microarray data from this article will be deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus and can be consulted at CATdb (http://urgv.evry.inra.fr/cgi-bin/projects/CATdb/consult_expce.pl?experiment_id=256).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Characterization of the gr1 mutant.

Supplemental Figure S2. Glutathione and ascorbate status in gr1 and cat2 mutants grown at high CO2 and then transferred to air in 8-h or 16-h days.

Supplemental Figure S3. Analysis of the conditional genetic interaction between cat2 and gr1 in an allelic double cat2 gr1 mutant.

Supplemental Figure S4. Quantitative PCR confirmation of changes in JA-linked genes in cat2 and cat2 gr1.

Supplemental Figure S5. H2O2 visualization in leaves of Col-0, gr1, cat2, and cat2 gr1 in SD and LD conditions.

Supplemental Figure S6. Genevestigator analysis (Hruz et al., 2008) of responses of glutathione-associated genes showing significantly different expression in cat2 and/or cat2 gr1 (Fig. 6).

Supplemental Table S1. PCR primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. Summary of modified daylength-dependent gene expression in gr1 and overlap with cat2 transcriptomes.

Supplemental Table S3. Complete data set of significantly modified genes in gr1, cat2, and cat2 gr1 in two daylength regimes.

Supplemental Table S4. List of JA-associated genes showing differential expression in cat2 and cat2 gr1 and relative expression values.

Supplemental Table S5. Summary of expression of GRXs, cytosolic TRXs, and related genes in cat2 and cat2 gr1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants, the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre for supply of gr1 seed stocks, and Gaëlle Cassin (Institut de Biologie des Plantes) for help with preliminary characterization of gr1. We are also grateful to Marie-Noëlle Soler and Spencer Brown (Imagif, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) for advice on confocal microscopy imaging and to Eddy Blondet (Unité de Recherche en Génomique Végétale) for help with microarray analyses.

References

- Achard P, Renou JP, Berthome R, Harberd NP, Genschik P. (2008) Plant DELLAs restrain growth and promote survival of adversity by reducing the levels of reactive oxygen species. Curr Biol 18: 656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aono M, Kubo A, Saji H, Tanaka K, Kondo N. (1993) Enhanced tolerance to photooxidative stress of transgenic Nicotiana tabacum with high chloroplastic glutathione reductase activity. Plant Cell Physiol 34: 129–135 [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (1999) The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 601–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L, Accotto G, Bechtold U, Creissen G, Funck D, Jimenez A, Kular B, Leyland N, Mejia-Carranza J, Reynolds H, et al. (2004) Evidence for a direct link between glutathione biosynthesis and stress defense gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 2448–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson-Bard A, Gravot A, Richaud P, Auroy P, Gaymard F, Taconnat L, Renou JP, Pugin A, Wendehenne D. (2009) Nitric oxide contributes to cadmium toxicity in Arabidopsis by promoting cadmium accumulation in roots and by up-regulating genes related to iron uptake. Plant Physiol 149: 1302–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent P, Creissen GP, Kular B, Wellburn AR, Mullineaux PM. (1995) Oxidative stress responses in transgenic tobacco containing altered levels of glutathione reductase activity. Plant J 8: 247–255 [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. (2009) Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 183–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan BB, Balmer Y. (2005) Redox regulation: a broadening horizon. Annu Rev Plant Biol 56: 187–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng NH, Liu JZ, Brock A, Nelson RS, Hirschi KD. (2006) AtGRXcp, an Arabidopsis chloroplastic glutaredoxin, is critical for protection against protein oxidative damage. J Biol Chem 281: 26280–26288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew O, Whelan J, Millar AH. (2003) Molecular definition of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle in Arabidopsis mitochondria reveals dual targeting of antioxidant defenses in plants. J Biol Chem 278: 46869–46877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbett CS, May MJ, Howden R, Rolls B. (1998) The glutathione-deficient, cadmium-sensitive mutant, cad2-1, of Arabidopsis thaliana is deficient in γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Plant J 16: 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creissen G, Reynolds H, Xue YB, Mullineaux P. (1995) Simultaneous targeting of pea glutathione reductase and of a bacterial fusion protein to chloroplasts and mitochondria. Plant J 8: 167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe ML, Serizet C, Thareau V, Aubourg S, Rouze P, Hilson P, Beynon J, Weisbeek P, van Hummelen P, Reymond P, et al. (2003) CATMA: a complete Arabidopsis GST database. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 156–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JDG. (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, Shulaev V, Schlauch K, Mittler R. (2005) Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 268–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després C, Chubak C, Rochon A, Clark R, Bethune T, Desveaux D, Fobert PR. (2003) The Arabidopsis NPR1 disease resistance protein is a novel cofactor that confers redox regulation of DNA binding activity to the basic domain/leucine zipper transcription factor TGA1. Plant Cell 15: 2181–2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich RA, Delaney TP, Uknes SJ, Ward ER, Ryals JA, Dangl JL. (1994) Arabidopsis mutants simulating disease resistance response. Cell 77: 565–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz KJ. (2003) Plant peroxiredoxins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54: 93–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SH, Lu QT, Zhang Y, Yang ZP, Wen XG, Zhang LX, Lu CM. (2009) Enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress in transgenic tobacco plants with decreased glutathione reductase activity leads to a decrease in ascorbate pool and ascorbate redox state. Plant Mol Biol 69: 577–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DP, Hawkins T, Hussey PJ, Edwards R. (2009) Enzyme activities and subcellular localization of members of the Arabidopsis glutathione transferase superfamily. J Exp Bot 60: 1207–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EA, Rawsthorne S, Mullineaux PM. (1990) Subcellular distribution of multiple forms of glutathione reductase in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Planta 180: 278–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshdat Y, Holland D, Faltin Z, Ben-Hayyim G. (1997) Plant glutathione peroxidases. Physiol Plant 100: 234–240 [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Lopez-Delgado H, Dat JF, Scott IM. (1997) Hydrogen peroxide- and glutathione-associated mechanisms of acclimatory stress tolerance and signalling. Physiol Plant 100: 241–254 [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. (2005) Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell 17: 1866–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Souriau N, Perret S, Lelandais M, Kunert KJ, Pruvost C, Jouanin L. (1995) Overexpression of glutathione reductase but not glutathione synthetase leads to increases in antioxidant capacity and resistance to photoinhibition in poplar trees. Plant Physiol 109: 1047–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnot S, Tamby JP, Martin-Magniette ML, Bitton F, Taconnat L, Balzergue S, Aubourg S, Renou JP, Lecharny A, Brunaud V. (2008) CATdb: a public access to Arabidopsis transcriptome data from the URGV-CATMA platform. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D986–D990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Dudoit S, Speed TP. (2003) Resampling-based multiple testing for microarray data analysis. Test 12: 1–77 [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LD, Vanacker H, Buchner P, Noctor G, Foyer CH. (2004) Intercellular distribution of glutathione synthesis and its response to chilling in maize. Plant Physiol 134: 1662–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilson P, Allemeersch J, Altmann T, Aubourg S, Avon A, Beynon J, Bhalerao RP, Bitton F, Caboche M, Cannoot B, et al. (2004) Versatile gene-specific sequence tags for Arabidopsis functional genomics: transcript profiling and reverse genetics applications. Genome Res 14: 2176–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Fujiwara T, Awazuhara M, Kimura T, Noji M, Saito K. (2003) Global expression profiling of sulfur-starved Arabidopsis by DNA macroarray reveals the role of O-acetyl-L-serine as a general regulator of gene expression in response to sulfur nutrition. Plant J 33: 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Laule O, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. (2008) Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinform 2008: 420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal A, Yabuta Y, Takeda T, Nakano Y, Shigeoka S. (2006) Hydroperoxide reduction by thioredoxin-specific glutathione peroxidase isoenzymes of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J 273: 5589–5597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot JP, Lemaire S, Rouhier N. (2008) The role of glutathione in photosynthetic organisms: emerging functions for glutaredoxins and glutathionylation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 143–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez A, Hernández JA, del Río L, Sevilla F. (1997) Evidence for the presence of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle in mitochondria and peroxisomes of pea leaves. Plant Physiol 114: 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzok SM, Fechner A, Bauer H, Ulschmid JK, Müller HM, Botella-Munoz J, Schneuwly S, Schirmer R, Becker K. (2001) Substitution of the thioredoxin system for glutathione reductase in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 291: 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski S, Gabrys H, Mateo A, Karpinska B, Mullineaux PM. (2003) Light perception in plant disease defence signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 390–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur N, Reumann S, Hu J. (2009) Peroxisome biogenesis and function. The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, doi/10.1199/tab.0123, http://www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsy G, von Ballmoos S, Suter M, Ruegsegger A, Galli U, Szalai G, Galiba G, Brunold C. (2000) Inhibition of glutathione synthesis reduces chilling tolerance in maize. Planta 211: 528–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koorneef A, Leon-Reyes A, Ritsema T, Verhage A, Den Otter FC, Van Loon LC, Pieterse CMJ. (2008) Kinetics of salicylate-mediated suppression of jasmonate signaling reveal a role for redox modulation. Plant Physiol 147: 1358–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranner I, Beckett RP, Wornik S, Zorn M, Pfeifhofer HW. (2002) Revival of a resurrection plant correlates with its antioxidant status. Plant J 31: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranner I, Birtic S, Anderson KM, Pritchard HW. (2006) Glutathione half-cell reduction potential: a universal stress marker and modulator of programmed cell death. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 2155–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinke O, Flemr M, Vergnolle C, Collin S, Renou JP, Taconnat L, Yu A, Burketovà L, Valentovà O, Zachowski A, et al. (2009) Phospholipase D activation is an early component of the salicylic acid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspensions. Plant Physiol 150: 424–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois-Meurinne M, Gachon CMM, Saindrenan P. (2005) Pathogen-responsive expression of glycosyltransferase genes UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 is necessary for resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139: 1890–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire SD. (2004) The glutaredoxin family in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms. Photosynth Res 79: 305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Lauri A, Ziemann M, Busch A, Bhave M, Zachgo S. (2009) Nuclear activity of ROXY1, a glutaredoxin interacting with TGA factors, is required for petal development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 429–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurin C, Andres C, Aubourg S, Bellaoui M, Bitton F, Bruyere C, Caboche M, Debast C, Gualberto J, Hoffmann B, et al. (2004) Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell 16: 2089–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty L, Siala W, Schwarzländer M, Fricker MD, Wirtz M, Sweetlove LJ, Meyer Y, Meyer AJ, Reichheld JP, Hell R. (2009) The NADPH-dependent thioredoxin system constitutes a functional backup for cytosolic glutathione reductase in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 9109–9114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May MJ, Vernoux T, Leaver C, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. (1998) Glutathione homeostasis in plants: implications for environmental sensing and plant development. J Exp Bot 49: 649–667 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Y, Siala W, Bashandy T, Riondet C, Vignols F, Reichheld JP. (2008) Glutaredoxins and thioredoxins in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou Z, Fan W, Dong X. (2003) Inducers of plant systemic acquired resistance regulate NPR1 function through redox changes. Cell 113: 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller S, Hilbert B, Dueckershoff K, Roitsch T, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Berger S. (2008) General detoxification and stress responses are mediated by oxidized lipids through TGA transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 768–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra S, Venkataramani S, Shen G, Wang J, Pasapula V, Lin Y, Korneyev D, Holaday AS, Zhang H. (2006) The Arabidopsis ascorbate peroxidase 3 is a peroxisomal membrane-bound antioxidant enzyme and is dispensable for Arabidopsis growth and development. J Exp Bot 57: 3033–3042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndamukong I, Al Abdallat A, Thurow C, Fode B, Zander M, Weigel R, Gatz C. (2007) SA-inducible Arabidopsis glutaredoxin interacts with TGA factors and suppresses JA-responsive PDF1.2 transcription. Plant J 50: 128–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Veljovic-Jovanovic SD, Driscoll S, Novitskaya L, Foyer CH. (2002) Drought and oxidative load in the leaves of C3 plants: a predominant role for photorespiration? Ann Bot (Lond) 89: 841–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oracz K, El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Kranner I, Bogatek R, Corbineau F, Bailly C. (2009) The mechanisms involved in seed dormancy alleviation by hydrogen cyanide unravel the role of reactive oxygen species as key factors of cellular signaling during germination. Plant Physiol 150: 494–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisy V, Poinssot B, Owsianowski L, Buchala A, Glazebrook J, Mauch F. (2007) Identification of PAD2 as a γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase highlights the importance of glutathione in disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant J 49: 159–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ruiz JM, Spinola MC, Kirchsteiger K, Moreno J, Sahrawy M, Cejudo FJ. (2006) NTRC is a high-efficiency redox system for chloroplast protection against oxidative damage. Plant Cell 18: 2356–2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queval G, Hager J, Gakière B, Noctor G. (2008) Why are literature data for H2O2 contents so variable? A discussion of potential difficulties in quantitative assays of leaf extracts. J Exp Bot 59: 135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queval G, Issakidis-Bourguet E, Hoeberichts FA, Vandorpe M, Gakière B, Vanacker H, Miginiac-Maslow M, Van Breusegem F, Noctor G. (2007) Conditional oxidative stress responses in the Arabidopsis photorespiratory mutant cat2 demonstrate that redox state is a key modulator of daylength-dependent gene expression and define photoperiod as a crucial factor in the regulation of H2O2-induced cell death. Plant J 52: 640–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queval G, Noctor G. (2007) A plate-reader method for the measurement of NAD, NADP, glutathione and ascorbate in tissue extracts: application to redox profiling during Arabidopsis rosette development. Anal Biochem 363: 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld JP, Khafif M, Riondet C, Droux M, Bonnard G, Meyer Y. (2007) Inactivation of thioredoxin reductases reveals a complex interplay between thioredoxin and glutathione pathways in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 19: 1851–1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey P, Cuiné S, Eymery F, Garin J, Court M, Jacquot JP, Rouhier N, Broin M. (2005) Analysis of the proteins targeted by CDSP32, a plastidic thioredoxin participating in oxidative stress responses. Plant J 41: 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L, Hallak-Herr E, Van Breusegem F, Rachmilevitch S, Barr JE, Rodermel S, Inzé D, Mittler R. (2002) Double antisense plants lacking ascorbate peroxidase and catalase are less sensitive to oxidative stress than single antisense plants lacking ascorbate peroxidase or catalase. Plant J 32: 329–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochon A, Boyle P, Wignes T, Fobert PR, Després C. (2006) The coactivator function of Arabidopsis NPR1 requires the core of its BTB/POZ domain and the oxidation of C-terminal oxidases. Plant Cell 18: 3670–3685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Milla MA, Maurer A, Huete AR, Gustafson JP. (2003) Glutathione peroxidase genes in Arabidopsis are ubiquitous and regulated by abiotic stresses through diverse signaling pathways. Plant J 36: 602–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki-Sekimoto Y, Taki N, Obayashi T, Aono M, Matsumoto F, Sakurai N, Suzuki H, Hirai MY, Noji M, Saito K, et al. (2005) Coordinated activation of metabolic pathways for antioxidants and defence compounds by jasmonates and their roles in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J 44: 653–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaeppi K, Bodenhausen N, Buchala A, Mauch F, Reymond P. (2008) The glutathione-deficient mutant pad2-1 accumulates lower amounts of glucosinolates and is more susceptible to the insect herbivore Spodoptera littoralis. Plant J 55: 774–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE. (2008) JAZing up jasmonate signaling. Trends Plant Sci 13: 66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RG, Creissen GP, Mullineaux PM. (2000) Characterisation of pea cytosolic glutathione reductase expressed in transgenic tobacco. Planta 211: 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada Y, Spoel SH, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K, Mou Z, Song J, Wang C, Zuo J, Dong X. (2008) Plant immunity requires conformational charges of NPR1 via S-nitrosylation and thioredoxins. Science 321: 952–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taki N, Sasaki-Sekimoto Y, Obayashi T, Kikuta A, Kobayashi K, Ainai T, Yagi K, Sakurai N, Suzuki H, Masuda T, et al. (2005) 12-Oxo-phytodienoic acid triggers expression of a distinct set of genes and plays a role in wound-induced gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139: 1268–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki M, Freeman JL, Pilon-Smits EAH. (2008) Cooperative ethylene and jasmonic acid signaling regulates selenite resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 146: 1219–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzafrir I, Pena-Muralla R, Dickerman A, Berg M, Rogers R, Hutchens S, Sweeney TC, McElver J, Aux G, Patton D, et al. (2004) Identification of genes required for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 135: 1206–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veljovic-Jovanovic SD, Pignocchi C, Noctor G, Foyer CH. (2001) Low ascorbic acid in the vtc-1 mutant of Arabidopsis is associated with decreased growth and intracellular redistribution of the antioxidant system. Plant Physiol 127: 426–435 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernoux T, Wilson RC, Seeley KA, Reichheld JP, Muroy S, Brown S, Maughan SC, Cobbett CS, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, et al. (2000) The ROOT MERISTEMLESS1/CADMIUM SENSITIVE2 gene defines a glutathione-dependent pathway involved in initiation and maintenance of cell division during postembryonic root development. Plant Cell 12: 97–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollsnes AV, Erikson AB, Otterholt E, Kvaal K, Oxaal U, Futsaether C. (2009) Visible foliar injury and infrared imaging show that daylength affects short-term recovery after ozone stress in Trifolium subterraneum. J Exp Bot 60: 3677–3686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner U, Edwards R, Dixon DP, Mauch F. (2002) Probing the diversity of the Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase gene family. Plant Mol Biol 49: 515–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardman P. (2007) Fluorescent and luminescent probes for measurement of oxidative and nitrosative species in cells and tissues: progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 995–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]