Abstract

Objective: this analysis was to investigate the effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on cardiovascular risk factors in older women with frailty characteristics.

Design, setting and participants: the study was a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of 99 women (mean 76.6 ± 6.0 year) with the low DHEA-S level and frailty.

Intervention: participants received 50 mg/day DHEA or placebo for 6 months; all received calcium (1,000–1,200 mg/day diet) and supplement (combined) and cholecalciferol (1,000 IU/day). Women participated in 90-min twice weekly exercise regimens, either chair aerobics or yoga.

Main outcome measures: assessment of outcome variables included hormone levels (DHEA-S, oestradiol, oestrone, testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG)), lipid profiles (total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides), body composition measured by dual energy absorptiometry, glucose levels and blood pressure (BP).

Results: eighty-seven women (88%) completed 6 months of study; 88% were pre-frail demonstrating 1–2 frailty characteristics and 12% were frail with ≥3 characteristics. There were significant changes in all hormone levels including DHEA-S, oestradiol, oestrone and testosterone and a decline in SHBG levels in those taking DHEA supplements. In spite of changes in hormone levels, there were no significant changes in cardiovascular risk factors including lipid profiles, body or abdominal fat, fasting glucose or BP.

Conclusion: research to date has not shown consistent effects of DHEA on cardiovascular risk, and this study adds to the literature that short-term therapy with DHEA is safe for older women in relation to cardiovascular risk factors. This study is novel in that we recruited women with evidence of physical frailty.

Keywords: dehydroepiandrosterone, lipids, cardiovascular risk factors, elderly

Introduction

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is an anabolic hormone that naturally declines with age. It has been touted as the ‘fountain of youth’ hormone, and advertisers of nutritional supplements claim supplementation can build muscle tissue and enhance physical performance. In women, DHEA is the predominant androgenic producing hormone. DHEA is converted to DHEA-S (sulfated form) in the liver and subsequently converted to more active androgens in the adrenals and peripheral tissues including testosterone, 5-dihydrotestosterone and oestrogens. DHEA levels in women decline in a linear fashion with age. The change in the female sex hormone milieu, including DHEA, oestrogen and testosterone, occurs temporally with an increase in cardiovascular risk factors including changes in lipids and body fat content.

Women continue to have a high cardiovascular mortality, whereas men have seen a greater decline in cardiovascular mortality in the past 20 years [1]. Older women have the highest prevalence of cardiovascular disease which has been associated with changes in body composition, rising LDL and decreasing HDL [1, 2]. The effect of the sex hormones on cardiovascular health is unclear with no consensus on whether oestrogen and testosterone exert beneficial or detrimental effect on the ageing cardiovascular system. Much interest and research in the last 15 years has focused on the oestrogenic effects on the risk and progression of cardiovascular disease. Observational studies suggested cardiovascular benefit in post-menopausal women [3], but large randomised, controlled trials of oestrogen replacement revealed no benefit in either primary or secondary prevention of heart disease [4, 5]. The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study found that there was no benefit to hormone replacement in women with established coronary artery disease (CAD) and an increase of coronary heart disease events was found in the first year of the trial [5]. The results of these studies have greatly impacted clinical practice in regard to hormone replacement in women. Many physicians have chosen to avoid hormonal replacement completely. Despite this, there remain many unanswered questions as to the role of the hormonal milieu in cardiovascular disease, cholesterol and body fat in older women. The ratio of oestrogens to testosterone, which are both low in older women, may be an important issue which has not been addressed in oestrogen repletion studies. Since DHEA is a precursor to both oestrogen and testosterone, it has the potential for an inimitable effect on cardiovascular risk factors and body fat.

DHEA supplementation has been studied in a variety of trials of both men and women with mixed results. To date no trials have evaluated the effect of DHEA supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in older women in which frailty was also evaluated. This analysis is warranted due to the known association of frailty with cardiovascular disease.

In this secondary analysis, we examined the effects of DHEA supplementation on the lipids and body fat in older post-menopausal women who were exercising, either using chair aerobics or yoga. Women were selected for low DHEA-S levels and some impairment in physical performance, a group we felt might be more likely to gain from DHEA therapy. In this analysis, we were able to assess the combination of exercise and DHEA in older women with frailty characteristics. We hypothesised that frailer, older women who exercise and take DHEA would have a reduction in abdominal fat and reduction in LDL cholesterol.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut Health Center approved the study, and all women gave written informed consent prior to screening evaluation. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate effects of 6-month oral DHEA on bone and frailty and is presented elsewhere (paper under review). The inclusion and exclusion criteria focused, therefore, on bone and frailty parameters. The women were recruited from the community through mailings. Women were aged 65 years and older and selected for DHEA levels below 550 ng/dL, the lower 50% of DHEA-S levels from a previous study of older women [6]. Selected women demonstrated some level of frailty (pre-frailty or frailty) and therefore had at least one of the five frailty criteria defined by Fried et al. [7] which includes self-reported weight loss of ≥10 lb in the preceding year, grip strength measured by hand-held Jamar dynamometer, sense of exhaustion as evaluated by two questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [8], walking speed by an 8-ft walk and level of physical activity reported in kilocalories per week from the Physical Activity Scale in the Elderly [9]. Women also had to have a bone mineral density of <−1.0 at the hip or spine. Exclusion criteria were: (i) disease of bone metabolism (i.e. Paget’s disease, osteomalacia, hyperparathyroidism); (ii) history of pituitary disease; (iii) consumption of more than three alcoholic drinks per day; (iv) the use of androgen, oestrogen or DHEA in the preceding year; (v) current use of antiresorptive agents such as calcitonin or bisphosphonates; (vi) metastatic or advanced cancer; (vii) current chemotherapy or radiation treatment and (viii) advanced liver or renal disease such that the subjects are unlikely to complete the 6-month intervention.

Treatment

Women were randomised in a double-masked manner to receive either DHEA supplement (50 mg/day) or a matching placebo. Each subject was randomly assigned to one of the four groups: (i) DHEA + yoga, (ii) DHEA + aerobics, (iii) placebo + yoga or (iv) placebo + aerobics, using a random number generator such that equal numbers were recruited into each group. The subjects were randomised into 20 subjects at a time, so that for each set of 20, five subjects were assigned to each group. A randomisation list was provided to the research pharmacist who had no direct contact with the research participants. DHEA/placebo was supplied by Charles Hakala, PhD, Belmar Pharmacy, Lakewood, CO. All women were instructed to take 1,000–1,200 mg/day of calcium through diet and supplementation and 1,000 IU of cholecalciferol.

Exercise prescription

The subjects were scheduled for two 90-min sessions per week of either yoga or chair aerobics. Yoga sessions were conducted by a certified practitioner, and chair aerobics, utilising commercially available tapes with supervision by an exercise instructor. Class sizes were comparable and each session was facilitated by an instructor for equal attention between exercise types. Attendance was recorded at each session for compliance.

Evaluations

Participants in the study underwent medical history, physical exam and measurement of fasting DHEA-S at screening. Baseline and 6-month assessment of outcome variables included serum DHEA-S and other sex hormone levels, cholesterol profiles, fasting glucose, dual energy absorptiometry for body composition, frailty evaluation and blood pressure (BP). Side effects or adverse events were documented throughout the study during the exercise sessions and formal questionnaires administered at 3 and 6 months.

Biochemical measurement

Blood was collected between 0700 and 0900 h after a 10–12-h fast. DHEA-S and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) were measured by immunoassay (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Immulite 1000) with sensitivity of 5 nmol/L and 0.2 nmol/L, respectively. Testosterone and oestradiol were done using enzyme immunoassay and oestrone using radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Systems Lab, Inc. Webster, TX), intra-assay variability <6.5%. The detection limit of the oestradiol assay is 0.6 pg/mL. Cholesterol and glucose measurements were performed on the Beckman Unicel DxC Chemistry Analyzer with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 2.0.

Body composition

Whole body dual X-ray absorptiometry using a DPX-IQ scanner (GE Medical Systems Lunar, Madison, WI), all scans were obtained by the same certified technician. Whole body scan provided total fat mass and abdominal fat mass (kilogramme).

Statistical analysis

Analysis was done on those individuals who had completed the study (n = 88; 45 vs 43). Reanalysis was performed using the individuals that remained on study medications throughout the 6 months (n = 77), but intention-to-treat analysis of 88 finishers presented: there were no significant differences in the results between the sample of 77 or 88. Baseline and clinical characteristics for DHEA and placebo were compared using one-way analysis of variance and chi-square tests, respectively. Using analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA), we tested the effect of DHEA on the outcomes after 6 months of drug intervention, co-varying for the exercise intervention and baseline measures. No effect of exercise intervention was found in any analysis. Additional analysis included ANCOVA co-varying for exercise, baseline measures and for number of frailty characteristics present; no change in the presented outcomes was found. Paired t-tests were used to detect change within each group over time. To correct for outliers and non-normally distributed measures, we calculated the positive square root; variables that required square root conversion included fat mass abdominal fat and BP readings. Sample size estimates were made for the primary hypothesis of strength and were calculated to detect changes in leg press strength of 45 N and are presented elsewhere. For this secondary analysis of lipids and body fat, the analysis had 80% power (significance 5%) to detect changes of 20 mg/dL in total cholesterol and 3.9% in fat mass or abdominal fat. All analyses were done using SPSS version 16.0.

Results

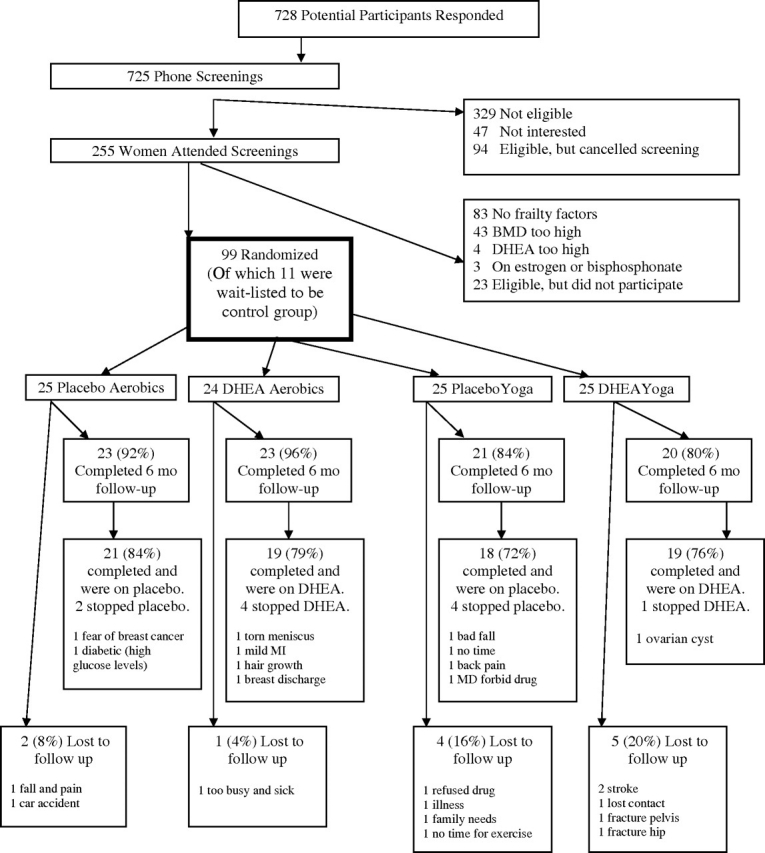

Two hundred and fifty-five women attended the pre-screening visit, but 156 were excluded due to no frailty characteristics, bone mineral density too high, DHEA levels too high, receiving oestrogen or bisphosphonates not reported on the telephone pre-screening or chose not to participate. A total of 99 women were randomly assigned to treatment or placebo, yoga or aerobics. Data for analysis is available for 87 women; 12 women were lost to analysis for several reasons including stroke, hip fracture, pelvic fracture, fall, car accident or lost interest in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics for those on DHEA vs placebo. Eighty-nine percent of the women met the criteria for pre-frail (with 1–2 of the physical characteristics) and 11% met the criteria for frail demonstrating three or more of the five characteristics. At baseline, there were trends for differences between groups in diastolic BP and triglycerides. Hormonal response to 6 months of DHEA was evident with all hormone levels increasing including DHEA, oestradiol, oestrone and testosterone. A significant decline in SHBG accompanied these hormone changes, as expected, in the DHEA group (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for women to receive DHEA or placebo

| DHEA (49) | Placebo (50) | Total sample (99) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Age (years) | 76.4 ± 6.2 | 76.9 ± 5.8 | 76.6 ± 6.0 | 0.68 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 6.2 | 28.0 ± 6.8 | 27.7 ± 6.5 | 0.67 |

| (n = 39) | (n = 39) | (78) | ||

| Systolic BP | 136 ± 20 | 132 ± 16 | 134 ± 18 | 0.37 |

| Diastolic BP | 77 ± 10 | 73 ± 10 | 75 ± 10 | 0.054 |

| (47) | (50) | (97) | ||

| Co-morbidity (%) | ||||

| Coronary heart disease | 13 (6) | 14 (7) | 13 (13) | 0.86 |

| Diabetes | 13 (6) | 6 (3) | 9 (9) | 0.25 |

| Stroke | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 4 (4) | 0.32 |

| Hypertension | 40 (19) | 46 (23) | 43 (42) | 0.58 |

| Depressed (≥16 CES-D) | 21 (10) | 10 (5) | 16 (15) | 0.15 |

| Race (%) | 0.44 | |||

| White | 89 (44) | 92 (46) | 91 (90) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Black | 9 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (6) | |

| Other | 0 | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Education (%) | 0.10 | |||

| High school | 26 (12) | 36 (18) | 31 (30) | |

| College | 38 (18) | 38 (19) | 38 (37) | |

| Postgraduate | 36 (17) | 26 (13) | 31 (30) | |

| Marital status (%) | 0.47 | |||

| Single | 15 (7) | 4 (2) | 9 (9) | |

| Married | 36 (17) | 42 (21) | 38 (38) | |

| Divorced/separated | 17 (8) | 16 (8) | 16 (16) | |

| Widowed | 32 (15) | 38 (19) | 34 (34) | |

| Smoker (%) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.53 |

| Medications (%) | ||||

| ACE inhibitor | 29 (12) | 23 (11) | 26 (23) | 0.53 |

| Beta blocker | 24 (10) | 34 (16) | 30 (26) | 0.32 |

| Antihistamine | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 5 (4) | 0.89 |

| Aspirin | 10 (4) | 13 (6) | 11 (10) | 0.66 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 20 (8) | 23 (11) | 22 (19) | 0.66 |

| Diuretic | 29 (12) | 36 (17) | 33 (29) | 0.49 |

| Statins | 32 (15) | 40 (20) | 36 (35) | 0.41 |

| Oestradiol (pg/mL) | 22.6 ± 7.6 | 22.0 ± 6.5 | 22.3 ± 7.0 | 0.69 |

| Oestrone (pg/mL) | 31.6 ± 10.5 | 31.7 ± 13.6 | 31.7 ± 12.1 | 0.95 |

| Testosterone (pg/mL) | 245.2 ± 123.4 | 251.0 ± 138.4 | 248.1 ± 130.6 | 0.83 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 63.0 ± 25.2 | 56.4 ± 22.8 | 59.7 ± 24.1 | 0.18 |

| DHEA (μg/dL) | 30.4 ± 13.0 | 31.5 ± 15.0 | 31.0 ± 14.0 | 0.70 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 209 ± 40 | 207 ± 36 | 208 ± 38 | 0.81 |

| HDL | 58 ± 14 | 58 ± 16 | 58 ± 15 | 0.96 |

| LDL | 131 ± 35 | 125 ± 35 | 128 ± 35 | 0.36 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 100 ± 54 | 123 ± 68 | 111 ± 62 | 0.07 |

| Frailty | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Pre-frail | 92 (45) | 86 (43) | 89 (88) | 0.36 |

| Frail | 8 (4) | 14 (7) | 11 (11) | |

| Frailty characteristics | ||||

| Handgrip | 82 (41) | 79 (38) | 81 (79) | 0.72 |

| Sense of exhaustion | 25 (7) | 31 (9) | 28 (16) | 0.61 |

| Walk speed | 8 (4) | 12 (6) | 10 (10) | 0.46 |

| Weight loss | 18 (9) | 16 (8) | 17 (17) | 0.82 |

| Physical activity | 14 (7) | 11 (5) | 12 (12) | 0.59 |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

Table 2.

Hormones and cardiovascular risk factors changes with DHEA or placebo: baseline to 6-month measurements

| Outcomes | DHEA(43) | Placebo(44) | Co-efficient ± SE | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormones | 0 m | 6 m | 0 m | 6 m | |||

| DHEA (μg/dL) | 29.9 ± 12.4 | 159.9 ± 115.4* | 31.1 ± 15.0 | 37.5 ± 49.4 | 124.3 ± 18.5 | 87.5 to 161.1 | <0.001 |

| Oestradiol (pg/mL) | 21.2 ± 6.2 | 29.4 ± 10.2* | 21.4 ± 6.5 | 21.7 ± 8.7 | 7.9 ± 1.6 | 4.7 to 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Oestrone (pg/mL) | 30.8 ± 10.1 | 56.2 ± 22.9* | 30.9 ± 12.7 | 30.9 ± 15.7 | 25.4 ± 3.5 | 18.3 to 32.4 | <0.001 |

| Testosterone (pg/mL) | 230.3 ± 116.2 | 571.4 ± 320.3* | 247.1 ± 141.8 | 252.3 ± 150.9 | 332.3 ± 48.6 | 235.7 to 429.0 | <0.001 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 62.0 ± 25.4 | 54.5 ± 24.1* | 56.8 ± 22.7 | 58.5 ± 22.2 | −8.5 ± 2.3 | −13.0 to −3.9 | <0.001 |

| Lipids | |||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 206 ± 37 | 201 ± 42 | 209 ± 36 | 207 ± 39 | −3.5 ± 5.4 | −14.2 to 7.1 | 0.51 |

| HDL | 58.8 ± 13.9 | 56.4 ± 16.9 | 59.0 ± 16.5 | 59.3 ± 14.7 | −2.7 ± 2.1 | −6.9 to 1.4 | 0.20 |

| LDL | 128.7 ± 33.0 | 127.0 ± 37.7 | 126.1 ± 34.6 | 124.8 ± 35.3 | −0.09 ± 4.6 | −9.3 to 9.1 | 0.99 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 92.1 ± 42.6 | 86.3 ± 46.0 | 117.5 ± 63.8 | 112.6 ± 53.3 | −12.3 ± 8.7 | −29.5 to 5.0 | 0.16 |

| Body composition | |||||||

| Fat mass (%) | 39.6 ± 7.5 | 39.7 ± 6.8 | 38.8 ± 7.6 | 38.8 ± 7.7 | 0.16 ± 0.41 | −0.65 to 0.97 | 0.55 |

| Abdominal fat (%) | 37.8 ± 7.1 | 37.6 ± 6.3 | 37.1 ± 7.8 | 37.2 ± 8.2 | −0.19 ± 0.5 | −1.2 to 0.8 | 0.93 |

| Metabolic parameter | |||||||

| Fasting glucose | 90.3 ± 17.7 | 90.0 ± 10.6 | 99.7 ± 28.7 | 92.5 ± 16.4 | 0.34 ± 2.6 | −4.9 to 5.5 | 0.88 |

| BP | (30) | (28) | |||||

| Systolic BP | 132 ± 20 | 135 ± 14 | 134 ±15 | 133 ± 20 | 1.9 ± 4.4 | −7.0 to 10.8 | 0.60 |

| Diastolic BP | 76 ± 9 | 73 ± 10 | 73 ± 8 | 74 ± 9 | −1.9 ± 2.4 | −6.7 to 2.9 | 0.41 |

CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

signifies statistical significance at P < 0.05 by paired t-test for within group change.

Outcomes were evaluated using ANCOVA controlling for baseline measures and the exercise intervention; DHEA vs placebo was the primary predictor.

There were no significant changes in measurable cardiovascular risk factors between groups or within groups from 0 to 6 months. Abdominal adiposity did not change significantly within or between groups. Although there was a slight reduction of HDL and in triglycerides in the DHEA group, this did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). There was no change in fasting glucose levels. There was no difference between exercise groups when exercise groups were included in analysis (data not shown). No interaction was found between DHEA supplementation and exercise group. Further, when presence of frailty characteristics was included in the analysis, no changes in abdominal fat, lipids or BP were found (data not shown).

There were no differences between DHEA and placebo in side effects noted (P = 0.21). Six events (2 strokes, 1 myocardial infarction, 2 falls with fracture and a torn meniscus) occurred after randomisation but before study participation occurred and are not included in the analysis. Of the remaining 23 noted adverse events, 14 occurred in the DHEA group and 9 in the placebo group. Events included six musculoskeletal (3 DHEA/3 placebo), cardiovascular (1 DHEA/1 placebo), falls (2 DHEA/4 placebo), breast/ovarian (3 DHEA/0 placebo), hair growth (1 DHEA/0 placebo) and miscellaneous including gout, panic attack, vertigo, pneumonia, light-headed, hyperglycaemia and rib fractures after an accident (4 DHEA group/1 placebo).

Discussion

We found no significant change in the cardiovascular risk profile or abdominal adiposity in DHEA-deficient older women with some level of frailty, similar to the conclusion of a review of non-frail adults [10]. DHEA supplementation increased the concentration of all sex hormones studied indicating a good therapeutic response. DHEA-S levels increased 5-fold, equal to those seen in a typical young adult [11] and similar to increases seen in other studies of older adults using 50 mg/day supplementation with DHEA [12–18]. Other studies have reported increases in oestrogen and testosterone levels similar to those we reported [12, 13, 16, 17]. The increases in oestradiol and oestrone levels reach those seen in pre-menopausal women, and the levels of testosterone are greater than those of pre-menopausal women [19].

Previous cross-sectional and interventional studies reporting on the effect of DHEA on the lipid profile have been mixed. A cross-sectional study showed a positive correlation between DHEA and HDL levels in post-menopausal women [20] while another study showed a similar correlation but only in men [21]. With DHEA supplementation, one study in which DHEA-S increased but testosterone did not demonstrate benefit to multiple components of the lipid profile [22]. One study found no change in HDL compared to placebo despite a robust hormonal response [23]. Another study demonstrated that the addition of DHEA supplementation to exercise did not improve HDL levels above exercise alone [12]. A third study showed a small decrease in HDL with DHEA but no change to LDL or triglycerides in both older men and women [13].

DHEA-S did not affect fat mass or glucose levels in our study. The work of others in this area has been varied. Two other studies using similar doses of DHEA in men and women found no change in body composition, fasting glucose, post-prandial glucose metabolism or insulin sensitivity [13, 14, 24]. In contrast, a study of older adults did find that DHEA decreased visceral fat area, measured by computed tomography, and decreased insulin levels with no change in fasting glucose levels [17]. Another study found a decrease in fat mass in men on DHEA 100 mg/day, but not in women and no change in insulin or glucose in either men or women [25]. In other studies in which exercise was used in combination with DHEA supplementation, DHEA offered no additional benefit in body fat, insulin sensitivity or glucose levels beyond that of exercise alone [12].

Although DHEA supplementation increases both testosterone and oestrogen levels, supplementation with either testosterone or oestrogen alone does not necessarily produce the same effect on the lipid profile. Oral testosterone supplementation consistently shows a detrimental effect on HDL and LDL levels, although an improvement in triglyceride levels is seen. Little information is available on lipid profiles using patches or sublingual supplementation [26]. Two small studies of testosterone and oestrogen replacement (one oral, one implant) vs oestrogen alone have demonstrated no increase in percentage body fat or abdominal/trunk fat [27, 28], results different than those seen in our study in which testosterone increases were indirect via DHEA supplementation rather than oral testosterone supplementation that requires hepatic metabolism. Oestrogen has been shown to decrease LDL cholesterol and increase HDL as well as fasting glucose [29, 30].

Finally, we did not find significant changes in BP, although our sample size was small. Other studies of DHEA in older adults have not specifically addressed hypertension, but in a retrospective study of transsexuals there was no excess of cardiovascular mortality compared to the general female population [31], and in women with adrenal insufficiency no changes in cardiovascular risk were found including 24-h BP monitoring [32]. The larger studies of oestrogen replacement have similarly not found BP changes to be a major factor [33] so that the modest increase in oestrogen we found would not be likely to result in BP changes. Few trials of testosterone replacement in older women exist, but reports from studies in all women suggest that BP remains unchanged [31].

Conclusion

DHEA is used by some older women as a hormonal replacement as it increases both testosterone and oestrogen levels. Many individuals take DHEA over-the-counter with hopes to improve libido, strength and sense of well being. Research to date has not shown consistent effects of DHEA on cardiovascular risk, and this study adds to the literature that short-term therapy with DHEA is safe for older women in relation to cardiovascular risk factors. This study is novel in that we recruited women with evidence of physical frailty.

Key points

Older frail women were able to tolerate low-level exercise and DHEA supplementation (50 mg/day) for 6 months without significant adverse effects.

DHEA supplementation (50 mg) increased hormone levels including DHEA-S, oestrone, oestradiol and testosterone levels in older frail women.

Older frail women participating in a low-level exercise programme and receiving DHEA supplementation did not have significant changes in cardiovascular risk factors including lipid profiles, BP, body composition or fasting glucose.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the National Aeronautic and Space Agency (NASA) NNG04GK63G and the General Clinical Research Center (MO1-RR06192).

A.M.K. was responsible for intellectual content of the paper by conception and design, obtaining funding, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of results, drafting and revision of the manuscript, administrative, technical and material support and supervision. A.K. was responsible for analysis and interpretation of results, drafting and revision of the manuscript and technical support. J.B. was responsible for acquisition of data, drafting and revision of the manuscript and technical support. R.F. was responsible for intellectual content of the paper by analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting and revision of the manuscript. J.A.B. was responsible for intellectual content of the paper by analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting and revision of the manuscript. R.S.B. was responsible for intellectual content of the paper by analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors give final approval to the manuscript submitted. We certify that all affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation with a financial interest are disclosed.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevenson R, Ranjadayalan K, Wilkinson P, Roberts R, Timmis AD. Short and long term prognosis of acute myocardial infarction since introduction of thrombolysis. BMJ. 1993;307:349–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6900.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen and progestin use and the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:453–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prestwood KM, Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Kulldorff M. Ultralow-dose micronized 17beta-estradiol and bone density and bone metabolism in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1042–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:28–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<28::aid-jclp2270420104>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tchernof A, Labrie F. Dehydroepiandrosterone, obesity and cardiovascular disease risk: a review of human studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:1–14. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tummala S, Svec F. Correlation between the administered dose of DHEA and serum levels of DHEA and DHEA-S in human volunteers: analysis of published data. Clin Biochem. 1999;32:355–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igwebuike A, Irving BA, Bigelow ML, Short KR, McConnell JP, Nair KS. Lack of dehydroepiandrosterone effect on a combined endurance and resistance exercise program in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:534–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair KS, Rizza RA, O’Brien P, et al. DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1647–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Percheron G, Hogrel JY, Denot-Ledunois S, et al. Effect of 1-year oral administration of dehydroepiandrosterone to 60- to 80-year-old individuals on muscle function and cross-sectional area: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:720–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villareal DT. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on bone mineral density: what implications for therapy? Treat Endocrinol. 2002;1:349–57. doi: 10.2165/00024677-200201060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villareal DT, Holloszy JO. DHEA enhances effects of weight training on muscle mass and strength in elderly women and men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E1003–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00100.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villareal DT, Holloszy JO. Effect of DHEA on abdominal fat and insulin action in elderly women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2243–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villareal DT, Holloszy JO, Kohrt WM. Effects of DHEA replacement on bone mineral density and body composition in elderly women and men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;53:561–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipsett M. Steroid hormones. In: Yen SSCJ, editor. Reproductive Endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noyan V, Yucel A, Sagsoz N. The association of androgenic sex steroids with serum lipid levels in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:487–90. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbasi A, Duthie EH , Sheldahl L, et al. Association of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, body composition, and physical fitness in independent community-dwelling older men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:263–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasco A, Frisina N, Morabito N, et al. Metabolic effects of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:457–61. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnhart KT, Freeman E, Grisso JA, et al. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation to symptomatic perimenopausal women on serum endocrine profiles, lipid parameters, and health-related quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3896–902. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu R, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, et al. Two years of treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone does not improve insulin secretion, insulin action, or postprandial glucose turnover in elderly men or women. Diabetes. 2007;56:753–66. doi: 10.2337/db06-1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales AJ, Haubrich RH, Hwang JY, Asakura H, Yen SS. The effect of six months treatment with a 100 mg daily dose of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on circulating sex steroids, body composition and muscle strength in age-advanced men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1998;49:421–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1998.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somboonporn W. Testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women: efficacy and safety. Semin Reprod Med. 2006;24:115–24. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobs AS, Nguyen T, Pace C, Roberts CP. Differential effects of oral estrogen versus oral estrogen-androgen replacement therapy on body composition in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1509–16. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis SR, Walker KZ, Strauss BJ. Effects of estradiol with and without testosterone on body composition and relationships with lipids in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2000;7:395–401. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1016–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espeland MA, Hogan PE, Fineberg SE, et al. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on glucose and insulin concentrations. PEPI Investigators. Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1589–95. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Kesteren PJ, Asscheman H, Megens JA, Gooren LJ. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997;47:337–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2601068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christiansen JJ, Andersen NH, Sorensen KE, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone substitution in female adrenal failure: no impact on endothelial function and cardiovascular parameters despite normalization of androgen status. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:426–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:523–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]