Abstract

Motor evoked potentials (MEPs) study using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may give a functional assessment of corticospinal conduction. But there are no large studies on MEPs using TMS in myelopathy patients. The purpose of this study is to confirm the usefulness of MEPs for the assessment of the myelopathy and to investigate the use of MEPs using TMS as a screening tool for myelopathy. We measured the MEPs of 831 patients with symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy using TMS. The MEPs from the abductor digiti minimi (ADM) and abductor hallucis (AH) muscles were evoked by transcranial magnetic brain stimulation. Central motor conduction time (CMCT) is calculated by subtracting the peripheral conduction time from the MEP latency. Later, 349 patients had surgery for myelopathy (operative group) and 482 patients were treated conservatively (nonoperative group). CMCTs in the operative group and nonoperative group were assessed. MEPs were prolonged in 711 patients (86%) and CMCTs were prolonged in 493 patients (59%) compared with the control patients. CMCTs from the ADM and AH in the operative group were significantly more prolonged than that in the nonoperative group. All patients in the operative group showed prolongation of MEPs or CMCTs or multiphase of the MEP wave. MEP abnormalities are useful for an electrophysiological evaluation of myelopathy patients. Moreover, MEPs may be effective parameters in spinal pathology for deciding the operative treatment.

Keywords: Motor evoked potential, Transcranial magnetic stimulation, Central motor conduction time, Myelopathy, Diagnosis

Introduction

Recently, the number of patients with symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy has been increasing with the progressive aging of society. Severe myelopathy often shows a poor prognosis even after surgical treatment. The evaluation of patients with suspected myelopathy invariably requires neurological assessment and radiological investigations. Sometimes, however, neurological assessment can be difficult in patients with severe arthritis and senile dementia, and clinical presentation can be atypical in patients of advanced age. Moreover, when diagnosing myelopathy using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate spinal compression, severe spinal cord compression is often accompanied by mild symptoms, and mild compression is often accompanied by severe neurological symptoms.

On the other hand, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is applied as a quick and noninvasive technique to study conduction in the descending corticospinal pathways [1–4]. An electrophysiological test consisting of TMS of the brain and surface recording of the motor evoked potentials (MEPs) from the upper and lower extremity muscles helps localize the motor lesion to the spinal cord in myelopathy patients [5–8]. The purpose of this study is to confirm the usefulness of MEPs as a screening tool for the assessment of myelopathy. Furthermore, we investigate the use of MEPs obtained with TMS in the results of myelopathy patients requiring operative intervention.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 1995 and May 2008, we measured the MEPs of 831 patients (529 males and 302 females) with symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy. Presenting symptoms were bilateral hand or feet numbness, difficulty walking, clumsiness or weakness of limbs and imaging findings based on MRIs revealed cord compression which supported the clinical symptoms. Patients were aged 15–89 years (mean 61.9) at the time of examination. The diagnoses before the examination were cervical spondylotic myelopathy (547 patients), cervical spondylotic amyotrophy (105 patients), cervical disc herniation (66 patients), spinal tumor (52 patients), cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (50 patients), thoracic ossification of yellow ligament (14 patients) and thoracic ossification of longitudinal ligament (7 patients). Ten patients had a double diagnosis in these diseases. All patients provided informed consent prior to the initiation of the study.

Measurement of MEP

Surface-recording electrodes were bilaterally placed on the abductor digiti minimi (ADM) and abductor hallucis (AH) muscles using the standard belly-tendon method. TNS was delivered using a round 14-cm outer diameter coil (Model 200; Magstim, Whitland, UK), the center of which was held over the vertex of the cranium when MEP recordings were made from the ADM. A clockwise current in the left hemisphere and a counterclockwise current in the right hemisphere were used as stimulation. The magnetic stimulus intensity was set at 20% above the threshold for the MEPs. The coil was then shifted anteriorly when the MEP recordings were made from the AH muscles. The MEPs were recorded at least four times; all responses were superimposed and their latencies measured. Compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) and F-waves were recorded following continuous current stimulation at supramaximal intensity (0.2 ms square wave pulses) of the ulnar and tibial nerves at the wrist and ankle, respectively. Thirty-two serial responses were obtained and the shortest F-wave latency was measured.

All muscle responses were recorded using a commercially available system (Viking IV; Nicolet Biomedical, WI, USA) after they traversed a bandpass filter of 0.5–2,000 Hz. An epoch of 100 ms after stimulation was digitized at a 5 kHz sampling rate. The peripheral conduction time (PCT), excluding the turnaround time at the spinal motor neuron (1 ms), was calculated from the latencies of the CMAPs and F-wave as follows [9]: (latency of CMAPs + latency of F-wave − 1)/2. The conduction time from the motor cortex to the spinal motor neurons (i.e., the CMCT) was calculated by subtracting the PCT from the onset latency of the MEPs.

A total of 25 healthy controls were studied for comparison. The mean age was 29.2 years (range 22–43 years). The averaged MEPs latency from the ADM and AH in the control group were 21.6 ± 1.0 and 39.1 ± 1.8 ms, respectively. The averaged CMCTs of the ADM and AH in the control group were 8.0 ± 1.0 and 14.4 ± 1.1 ms, respectively. The electrophysiological data are presented as the mean ± SD. After the revision of height, data which exceeded +2SD from the control data were considered to be abnormal findings. And MEPs from the ADM over five phases were considered as abnormal findings [10]. We excluded patients with pacemakers or epilepsy from the examination criteria.

After detailed neurological assessment and radiological investigations, an operation was performed for selected patients that provided informed consent prior to the operation. We recommended the operation to patients with severe symptoms of myelopathy and imaging findings of obvious cord compression on MRIs which supported the clinical symptoms. Later, 349 patients had surgery (operative group) and 482 patients did not have surgery (nonoperative group). In the operative group, laminoplasty was performed in 267 patients, anterior or posterior fusion in 19 patients, tumor resection in 43 patients and laminectomy in 12 patients. CMCTs in the operative group and in the nonoperative group were assessed.

Statistical analysis

The PCT values were evaluated, comparing the right and left sides. Data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric statistical analysis; a P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

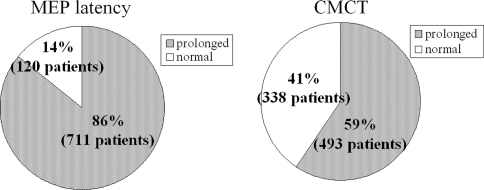

The average MEP latency of 831 patients from the ADM and AH was 23.7 ± 3.9 and 42.8 ± 6.7 ms, respectively. The averaged CMCT from the ADM and AH was 9.3 ± 3.4 and 17.3 ± 5.3 ms, respectively. MEPs were prolonged in 711 patients (86%) and CMCTs were prolonged in 493 patients (59%) compared with the control patients (Fig. 1). Two hundred and thirteen patients showed delayed CMCT from the AH and normal CMCT from the ADM. In these patients, 29 patients had thoracic spinal cord dysfunctions.

Fig. 1.

The average MEP latency and CMCT in 831 patients. MEPs were prolonged in 711 patients (86%) and CMCTs were prolonged in 493 patients (59%)

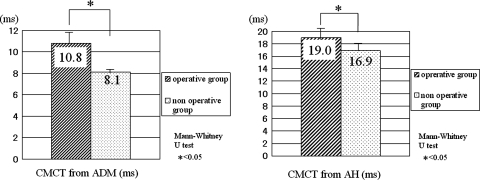

In the patients showing prolongation of MEP latency, 325 patients (46%) received surgical treatment. Among patients showing prolongation of CMCT, 262 patients (53%) received surgical treatment. All 349 patients in the operative group showed prolongation of MEP latency or CMCTs or multiphase of the MEP wave. The average CMCT from the ADM and AH in the operative group was 10.8 ± 1.4 and 19.0 ± 2.0 ms, respectively. The average CMCT from the ADM and AH in the nonoperative group was 8.1 ± 0.4 and 16.9 ± 1.4 ms, respectively. CMCTs from the ADM and AH in the operative group were significantly more prolonged than that in nonoperative group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). There were no complications concerning the examination.

Fig. 2.

CMCTs from the ADM and AH in the operative group and nonoperative group. The average CMCT from the ADM and AH in the operative group is 10.8 ± 1.4 and 19.0 ± 2.0 ms, respectively. The average CMCT from the ADM and AH in the nonoperative group is 8.1 ± 0.4 and 16.9 ± 1.4 ms, respectively. CMCTs from the ADM and AH in the operative group are significantly more prolonged than in the nonoperative group (P < 0.05)

Case presentation

Case 1

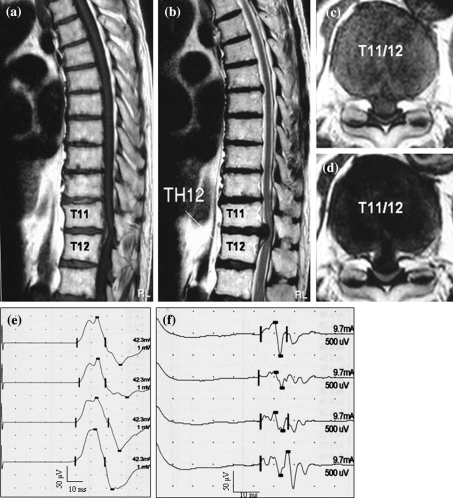

An 81-year-old man complained of several years history of progressive bilateral lower limb numbness as well as weakness and bladder disturbance. He had consulted a local doctor, but the focus was unclear. Tendon reflex was normal. Power was mildly reduced [manual muscle testing (MMT): 4/5] in both lower limbs. There was mild hypesthesia of these bilateral limbs. CMCT from the ADM was normal (CMCT from the right ADM and left ADM was 6.3 and 7.9 ms, respectively), but CMCT from the AH was prolonged (CMCT from the right AH and left AH was 21.8 and 20.8 ms, respectively). Magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed cord compression at T11/12 due to disc herniation. Surgery using electrophysiological evaluations was performed. Subsequently, his numbness and weakness of the bilateral lower limbs improved (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The patient was an 81-year-old man. Magnetic resonance image (MRI) showing cord compression at T11/12 due to disc herniation (a T1-weighted sagittal image, b T2-weighted sagittal image, c T1-weighted axial image, d T2-weighted axial image). CMCT from the ADM was normal, but CMCT from the AH was prolonged (e MEP from ADM, f MEP from AH)

Case 2

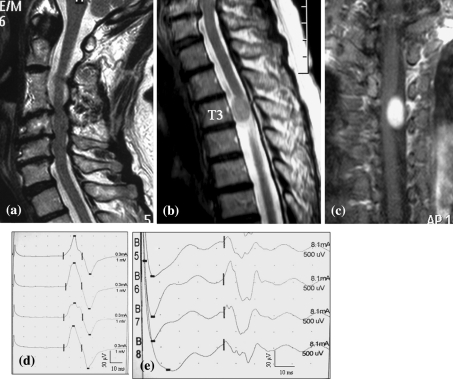

A 71-year-old lady had an episode of bilateral lower limb numbness. She had been treated by a local doctor for lumbar canal stenosis for several years. Subsequently, she felt bilateral upper limb numbness. On physical examination, tendon reflex and power were normal. But there was hypesthesia of her bilateral limbs. CMCT from the ADM was normal (CMCT from the right ADM and left ADM was 8.1 and 9.0 ms, respectively), and CMCT from the right AH was normal (CMCT from the right AH was 14.3 ms), but CMCT from the left AH was prolonged (CMCT from the left AH was 17.3 ms). PCTs from the upper limb and lower limb were prolonged (PCT from the right upper limb and left upper limb were 14.9 and 14.8 ms, respectively. PCT from the right lower limb and left lower limb were 27.8 and 28.3 ms, respectively.). MRI showed multiple-level cord compression at C3/4, 4/5, 5/6, and a spinal cord tumor at T3 level. In view of these findings, her symptoms were attributed to thoracic myelopathy related to a thoracic spinal tumor. The patient underwent tumor resection using electrophysiological evaluations and showed good improvement after surgery (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The patient was a 71-year-old woman. MRI showing multiple-level cord compression at C3/4, 4/5, 5/6 (a T2-weighted sagittal image), and spinal cord tumor at T3 level (b T2-weighted sagittal image, c Gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted coronal image). CMCT from the ADM was normal, but CMCT from the AH was prolonged (d MEP from ADM, e MEP from AH)

Discussion

This study showed that MEP abnormalities are useful for electrophysiological evaluation of myelopathy patients. Moreover, MEP findings may be effective parameters in spinal pathology for operative treatment decisions. To our knowledge, this study provides the largest amount of data addressing TMS evaluation in myelopathy patients.

Since the introduction of TMS of the human motor cortex, the use of MEPs in the evaluation of many kinds of myelopathy has been well described [11–14]. The conduction time from the motor cortex to the anterior horn cell (CMCT) is a measure of the integrity of corticospinal pathways [15]. In particular, there is a correlation between the CMCT prolongation and the clinical disability [12, 16]. Moreover, CMCT was found to be more prolonged in patients who had more severe cervical spinal cord compression as determined by MRI analysis [17]. Because of this delayed CMCT, it is suggested that CMCT prolongation is primarily due to corticospinal conduction block, rather than conduction delay [18–20]. On the other hand, there is no correlation in elderly patients over 70 years between CMCT and the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score, which reflects the severity of clinical disability [21]. When diagnosing elderly patients for myelopathy, it is important to evaluate generally not only CMCT, but also MEP latency and wave form.

In the diagnosis of myelopathy, conventional diagnostic methods such as neurologic findings, image study such as MRI and myelograms are usually performed, but conclusive diagnosis is sometimes difficult because many symptoms tend to be separate from the existing disease. And the MR images demonstrate morphological abnormalities of the cord but not functional impairment, and not all cord compression shown by MR images is associated with cord dysfunction [22]. In this regard, TMS could be an effective diagnostic tool. MEP studies using TMS also present a quantitative evaluation of myelopathy by TMS. Previous studies have indicated that MEPs may be a valuable tool in the assessment of the functional relevance of subclinical spondylotic cervical cord compression [23]. Furthermore, this test method has advantages in the evaluation of patients who have developed severe joint deterioration due to rheumatoid arthritis or who have difficulty in communicating or who have peripheral nervous disorders and, therefore, for whom neurological detection is difficult. Moreover, MEP helps localization of the site responsible for the main functional change for patients with the multilevel compression of the spinal cord, such as cervical spinal cord and thoracic spinal cord.

With the evidence provided by this large study presenting with symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy, MEPs were prolonged in 711 patients (86%) and CMCTs were prolonged in 493 patients (59%). The MEPs and CMCTs might be influenced with age. However, Chen et al. [24] reported that CMCT has no correlation or only a weak correlation with age in adults. An MEP study with TMS is a useful and noninvasive screening tool for myelopathy patients. Additionally, this study found that CMCTs from the ADM and AH in the operative group are significantly more prolonged than in the nonoperative group. All patients in the operative group showed prolongation of MEPs or CMCTs or multiphase of the MEP waves. There were some nonoperative patients in the CMCT or MEP prolongation group. These patients had a mild presentation of the symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy. They were observed in our outpatient clinic with clinical symptoms and electrophysiological findings.

TMS also has the potential to enable early diagnosis of myelopathy by detecting changes in CMCT and in MEP wave forms that reflect conduction times of the pyramidal tract, because early pathologic changes of cervical spondylotic myelopathy includes demyelination of the pyramidal tract [25, 26]. When considering details of the surgical treatment, MEPs also help when deciding the timing of the operation. In the diagnosis of myelopathy, an MEP study with TMS gives us a useful tool as well as neurologic findings and an image study.

Conclusions

In the 831 patients with symptoms and signs suggestive of myelopathy, MEPs were prolonged in 711 patients (86%) and CMCTs were prolonged in 493 patients (59%).

MEP abnormalities are useful for electrophysiological evaluation of myelopathy patients.

MEP findings may be an effective parameter in spinal pathology when deciding details of the surgical treatment.

References

- 1.Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985;1:1106–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess CW, Mills KR, Murray NMF. Measurement of central motor conduction in multiple sclerosis by magnetic brain stimulation. Lancet. 1986;2:355–358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linden RD, Zhang YP, Burke DA, et al. Magnetic motor evoked potential monitoring in the rat. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:205–210. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.91.2.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staudt M, Krageloh-Mann I, Holthausen H, et al. Searching for motor functions in dysgenic cortex: a clinical transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:69–77. doi: 10.3171/ped.2004.101.2.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen KM, Nasathurai S, Chavin JM, et al. The usefulness of central motor conduction studies in the localization of cord involvement in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:1220–1223. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199809)21:9<1220::AID-MUS18>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein CM, Fernandez-Beer E. Cervical magnetic stimulation: the role of the natural foramen. Neurology. 1991;41:677–680. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakolski DJ, Jarrat JA. Clinical evaluation of magnetic stimulation in cervical spondylosis. Br J Neurosurg. 1989;3:541–548. doi: 10.3109/02688698909002845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazzaro VD, Restuccia D, Colosimo C, et al. The contribution of magnetic stimulationof the motor cortex to the diagnosis of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Correlation of central motor conduction to distal and proximal upper limb muscles with clinical and MRI findings. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;85:311–320. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90107-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura J. Principles and pitfalls of nerve conduction studies. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:415–429. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka S, Fujimoto Y, Shirasu K et al (1997) Assessment of cervical flexion myelopathy for the motor function using transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Jpn Orthop Assoc 73(2),(3):S404 (in Japanese)

- 11.Kameyama O, Shibano K, Kawakita H, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in cervical spondylosis and spinal canal stenosis. Spine. 1995;20:1004–1010. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi J, Hirabayashi H, Hashidate H, et al. Assessment of cervical myelopathy using transcranial magnetic stimulation and prediction of prognosis after laminoplasty. Spine. 2008;33:E15–E20. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e5dae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taniguchi S, Tani T, Ushida T, et al. Motor evoked potentials elicited from erector spinae muscle in patients with thoracic myelopathy. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:567–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto Y, Oka S, Tanaka N, et al. Pathophysiology and treatment for cervical flexion myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(3):276–285. doi: 10.1007/s005860100344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavy DL, Wagner GL, Keunen RW, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: clinical and radiological correlations. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:235–241. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameyama O. Prediction of post-operative recovery rate in cervical myelopathy: is prognosis prediction possible? Electrodiagnosis Spine [Sekizui denki shindangaku] 1995;17:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo YL, Chan LL, Lim W, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation screening for cord compression in cervical spondylosis. J Neurol Sci. 2006;244:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko K, Taguchi T, Morita H, et al. Mechanism of prolonged central motor conduction time in compressive cervical myelopathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi K, Tanaka N, Kamei N, et al. Significant correlation between corticospinal tract conduction block and prolongation of central motor conduction time in compressive cervical myelopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;256:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakanishi K, Nobuhiro T, Fujiwara Y, et al. Corticospinal tract conduction block results in the prolongation of central motor conduction time in compressive cervical myelopathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:623–627. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka N, Yamada K. Preoperative electrophysiological assessments by motor evoked potentials in elderly patients with compressive cervical myelopathy. Monthly Book Orthopaedics. 2007;20(13):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka N, Fujimoto Y, Yasunaga U, et al. Functional diagnosis using multimodal spinal cord evoked potentials in cervical myelopathy. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s00776-004-0859-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bednarik J, Kadanka Z, Vohanka S, et al. The value of somatosensory and motor evoked potentials in pre-clinical spondylotic cervical cord compression. Eur Spine J. 1998;7(6):493–500. doi: 10.1007/s005860050113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen R, Cros D, Curra A, et al. The clinical diagnostic utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation: report of an IFCN committee. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(3):504–532. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogino H, Tada K, Okada K, et al. Canal diameter, anteroposterior compression ratio and spondylotic myelopathy of the cervical spine. Spine. 1983;8:1–15. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono K, Ebara S, Juji T, et al. Myelopathy hand. New clinical sighs of cervical cord damage. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1987;69:215–219. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]