Abstract

Patients with multisegmental degenerative disc disease (DDD) resistant to conservative therapy are typically treated with either fusion or non-fusion surgical techniques. The two techniques can be applied at adjacent levels using Dynesys® (Zimmer GmbH, Winterthur, Switzerland) implants in a segment-by-segment treatment of multiple level DDD. The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical and radiological outcome of patients treated using this segment-by-segment application of Dynesys in some levels as a non-fusion device and in other segments in combination with a PLIF as a fusion device. A consecutive case series is reported. The sample included 16 females and 15 males with a mean age of 53.6 years (range 26.3–76.4 years). Mean follow-up time was 39 months (range 24–90 months). Preoperative Oswestry disability index (ODI), back- and leg-pain scores (VAS) were compared to postoperative status. Fusion success and system failure were assessed by an independent reviewer who analyzed AP and lateral X-rays. Back pain improved from 7.3 ± 1.7 to 3.4 ± 2.7 (p < 0.000002), leg pain from 6.0 ± 2.9 to 2.3 ± 2.9 (p < 0.00006), and ODI from 51.6 ± 13.2% to 28.7 ± 18.0% (p < 0.00001). Screw loosening occurred in one of a total of 222 implanted screws (0.45%). The results indicate that segment-by-segment treatment with Dynesys® in combination with interbody fusion is technically feasible, safe, and effective for the surgical treatment of multilevel DDD.

Keywords: Hybrid stabilization, Segment-by-segment treatment, Dynesys, PLIF, Multilevel DDD treatment

Introduction

As there is no standard definition of disc degeneration, determinations of its presence and severity vary, largely depending upon whether radiographs, discography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to investigate the disc. The prevalence of disc-related degenerative findings on MRI of the lumbar spine varies greatly depending on the disc level and other factors such as age, environmental and behavioral influences, familial aggregation, and heritability [1]. Boden et al. [4] have shown that disc degeneration at an average of three levels can be seen in up to 90% of people over the age of 60 years. Little is known about the segmental distribution of degenerative disc disease (DDD) in individuals. As a rule, L4–5 and L5–S1 have the highest prevalence of all degenerative disc findings. The clinical significance of such findings is debatable, because these abnormalities are also commonly found in asymptomatic individuals [7, 9]. In contrast, Boos et al. [7] demonstrated that disc extrusion and neural compromise are common in patients with back pain and sciatica. Furthermore, in an MRI study of 148 subjects between 36 and 71 years of age, Jarvik et al. [23] concluded that moderate or severe central stenosis, root compression, and disc extrusions are likely to be diagnostically and clinically relevant. Next to Modic changes, which were consistently and strongly associated with low back pain (LBP), Kjaer et al. [30] also reported an increased, albeit weaker, odds ratio between LBP and hypointense disc signal, reduced disc height, annular tears, high-intensity zones, disc bulging, and anterolisthesis.

One of the most controversial topics in spine literature is the treatment of DDD. Most authors agree that non-surgical options should be the primary treatment of patients in DDD. Surgery may be indicated in cases that are unresponsive to conservative treatment. Surgery of the degenerative lumbar spine predominantly implements one or more of three strategies: decompression, stabilization, and correction of scoliotic or kyphotic deformity. Depending on the clinical and radiological manifestations of DDD, these procedures frequently need to be combined.

Spinal fusion is the established gold standard for the correction of true lumbar deformities. The role of lumbar fusion for the treatment of DDD remains in debate. Consequently an increasing number of alternatives to lumbar fusion have been introduced in recent years. These procedures aim to respect the integrity of the spinal motion segments and promote a balance of stability and natural motion. One representative in this group is the Dynesys® (Zimmer GmbH, Winterthur, Switzerland) system. First implanted in 1994 by Gilles Dubois, Dynesys® is a pedicle system providing mobile stabilization controlling motion in all three planes of space. It is designed to restore stability to treat painful conditions of degenerative origin such as unstable forms of degenerative disc disease or of lumbar stenosis. Thus, indications are local lumbar pain and/or radicular pain attributed to instability regardless of whether or not there is an accompanying neurological deficit. Dynesys® is also designed to stop further progression of minor deformities frequently associated with spinal stenosis, including degenerative spondylolisthesis, early degenerative scoliosis, or both. More details of the concept, technique, and clinical results of Dynesys® are available elsewhere [19, 40–44, 46, 51].

Multisegmental disc disease is common in symptomatic back patients. In such cases in the past a surgeon typically opted to perform either a fusion or non-fusion technique to alleviate symptoms associated with DDD. However, because lumbar motion segments vary in extent of degeneration and instability, it seems logical to address multilevel DDD segment by segment. Although advanced degeneration of an intervertebral disc (as described by Pfirrmann grade 5 [38]) as well as a gross instability of a motion segment should be treated with fusion, discopathy with still acceptable disc height (Pfirrmann grade 3 and 4), and absent gross instability can be treated with a motion-sparing, non-fusion technology.

Shortly after the introduction of Dynesys®, the author began to combine fusion and non-fusion techniques in the treatment of multisegmental DDD. Segment(s) requiring fusion were treated with posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) enhanced by pedicular instrumentation with Dynesys®. In these segments, Dynesys® serves as a posterior tension band. Symptomatic segments with less advanced changes were treated using Dynesys® as a dynamic stabilization device (see Fig. 1), i.e. the purpose for which it was originally designed. The present report describes clinical and radiographic results of this new stabilization technique, which was termed “Dynesys® hybrid stabilization”.

Fig. 1.

Combination of fusion and non-fusion techniques. Caudal segment: PLIF enhanced by Dynesys®; maximal compression is applied, and Dynesys® serves as a posterior tension band. Cranial segment: Dynesys® dynamic stabilization

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective study of a consecutive case series.

Patient sample

All patients who were treated using “Dynesys® hybrid stabilization” for DDD in the author’s clinic over a 5-year period were assessed. Inclusion criteria were: (a) symptomatic DDD, (b) associated spinal instability, (c) two or more affected vertebral motion segments, and (d) failure of conservative treatment for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria consisted in standard contraindications for fusion and dynamic stabilization techniques, including non-degenerative etiologies of instability (e.g. fractures, congenital scoliosis), tumor, metabolic bone diseases, severe degenerative scoliosis or kyphosis, and infection.

In total, 31 patients who presented with symptomatic DDD manifested by chronic low back pain and/or leg pain were included in the study population. The sample included 16 females (51.6%) and 15 males (48.4%). Mean age at surgery was 53.6 years (±12.9 years; range 26.3–76.4 years). Fifty-two percent (n = 16) had had one (7/16 patients) or more (9/16 patients) prior surgeries at one (13/16 patients) or two (3/16 patients) of the segments currently requiring operative treatment. Surgeries performed prior to Dynesys® were discectomy/nucleotomy (n = 13), decompression (n = 2), and disc repair (n = 1).

Surgical planning

All patients presented multi-segmental painful DDD proven by segmental diagnostic assessment, using segmental infiltrations and discograms. Planning for the surgeries in this study involved:

identification of segments requiring operative treatment based on clinical and radiological evaluation,

- choice of procedure for each segment:

- Dynesys® stabilization plus decompression and fusion (PLIF),

- Dynesys® stabilization alone,

- Dynesys® stabilization plus decompression.

The indications for fusion were:

severely degenerative discs (Pfirrmann grade 5) with or without gross instability or gross instability with earlier degenerative changes (Pfirrmann grades 3 and 4),

cases of segments that had already undergone open operative intervention(s),

segments with lytic spondylolisthesis, because this is a contraindication for dynamic stabilization.

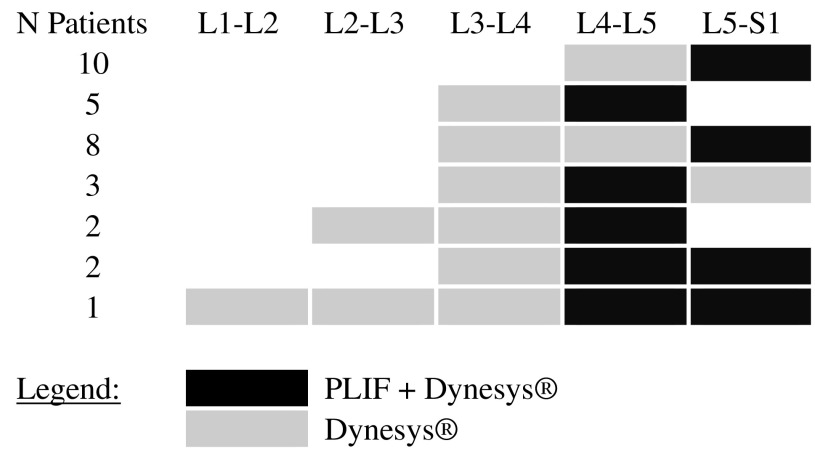

All the remaining painful lumbar segments in the patients were dynamically stabilized. Table 1 shows the distribution of fused and dynamically stabilized segments.

Table 1.

Segment-by-segment treatment overview

In each treated segment, Dynesys® was used either alone as non-fusion device or in combination with a PLIF procedure as a fusion device

Operative procedure

The dynamically stabilized segments reported in this study were instrumented according to the complete operative procedure as detailed in Stoll et al. [46].

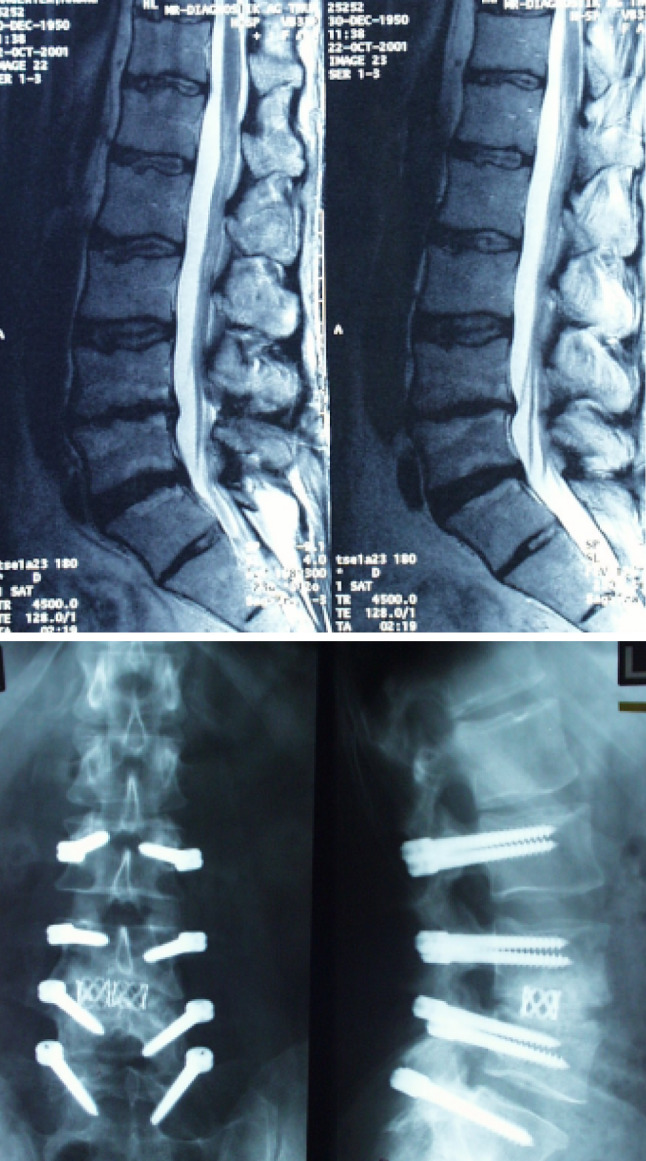

Segmental fusion was achieved by combining Dynesys® with a PLIF procedure using intervertebral cages. An example is shown in Fig. 2. In PLIF segments, Dynesys® acted as a pedicle screw-based posterior tension band. Therefore, the modular spacers were cut approximately 1–2 mm shorter than the measured distance between the two adjacent screw heads on each side, and the system was fixed under maximum compression, exceeding the 300 N recommended for dynamic stabilization. This further reduced the length of the spacer and compressed the facet joints adding to segmental stability. To achieve intervertebral fusion, any cage design can be combined with Dynesys®. In this study, Harms Titan® Mesh (DePuy Acromed, Raynham, MA, USA), L-Varlock® (Kiscomedica, St. Priest, France), Varilift® (Advanced Spine Fixation Systems Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), B-Twin® (Disc-O-Tech Medical Technologies Ltd., Herzeliya, Israel), and BAK Interbody Fusion System® (Zimmer GmbH, Winterthur, Switzerland) were used.

Fig. 2.

Example of a 51-year-old man with postdiscectomy syndrome at the level L3–L4 and degenerative disc disease proven by positive discography at L2–L3 and L4–L5. This patient suffered from low back pain and leg pain. Bone bridges 5 months postoperatively indicate successful fusion at L3–L4 (treated with Dynesys® and PLIF). The levels L2–L3 and L4–L5 were dynamically stabilized with Dynesys® only

Decompression by laminotomy or laminectomy was performed in all PLIF segments. The dynamically stabilized segments were decompressed by laminotomy if they showed radiological evidence of spinal canal stenosis.

Clinical assessment

The Oswestry disability index (ODI scale 0–100%) was used to assess functional impairment [12]. Leg and back pain were rated on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS) [54]. Pre-operative scores were compared to postoperative scores, and Wilcoxon test for paired data was applied for statistical evaluation.

Standard radiographic assessment included anterior/posterior (A/P) and lateral X-rays. The absence of radiolucency around the cage, no signs of cage subsidence or the presence of bridging bone in the intervertebral space were the criteria for a solid fusion. Screw loosening (defined as “continuous lucency ≥1 mm” around the screw [36]) and breakage of Dynesys® was also assessed on A/P and lateral X-rays. All patients signed the informed patient consent forms.

Results

Operative segments

A total of 80 lumbar segments were treated in 31 patients: 34 segments were fused and 46 segments were dynamically stabilized. Among these 46 segments, only two segments were decompressed during the operation. In 16 patients, fusion was performed because of previous surgery (discectomy and/or decompression) and severe disc degeneration. In five patients, degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis and instability was the indication for fusion. Three patients had a lytic spondylolisthesis at L5–S1, and seven patients had a fusion because of a severe DDD (Pfirrmann grade 5). In total, three patients had a two-level fusion: one patient had previous surgery at two segments and two patients had previous surgery at one level in combination with a severely degenerated adjacent segment (Pfirrmann grade 5). All segments that were dynamically stabilized had DDD with Pfirrmann grade 3 or 4. Three of these segments had undergone previous minor surgeries [percutaneous nucleotomy (n = 2) and microdiscectomy (n = 1)].

Procedures involved two segments (one segment fused, one segment dynamically stabilized) in 15 patients (48.4%), three segments in 15 patients (48.4%; one segment fused and two segments dynamically stabilized in 13 patients, two segments fused and one segment dynamically stabilized in 2 patients), and five segments in one patient (3.2%; two segments fused and three segments dynamically stabilized). See Table 1 for segment distribution.

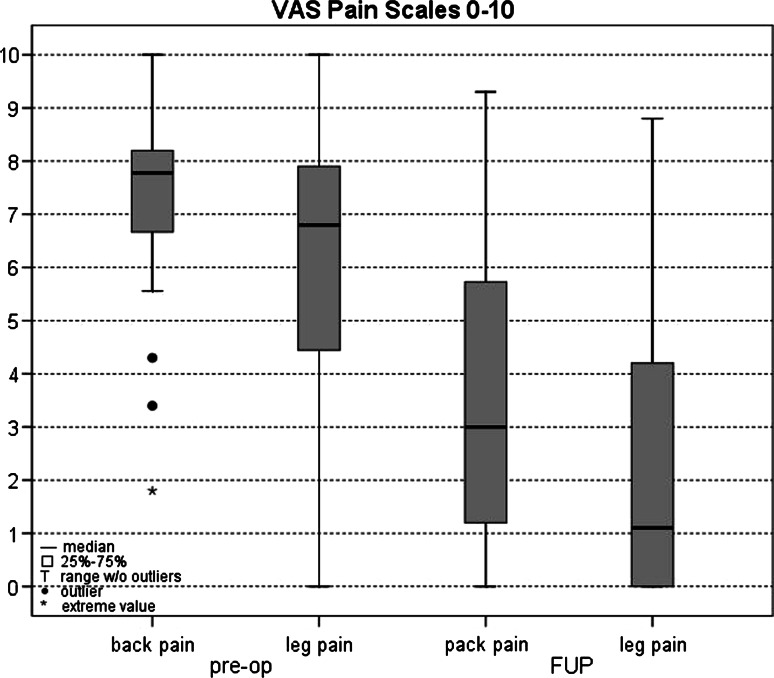

Patient self-rating outcomes

Mean follow-up was 39 months (range 24–90 months). Back pain improved from 7.3 ± 1.7 preoperatively to 3.4 ± 2.7 postoperatively and leg pain decreased from 6.0 ± 2.9 preoperatively to 2.3 ± 2.9 postoperatively (Fig. 3). These improvements were statistically significant for both leg pain (p < 0.00006) and back pain (p < 0.000002).

Fig. 3.

Back pain and leg pain visual analog scale (VAS) score before operation and at mean follow-up time of 39 months (range 24–90 months). These were the values for all 31 patients, including those who had postoperative complications

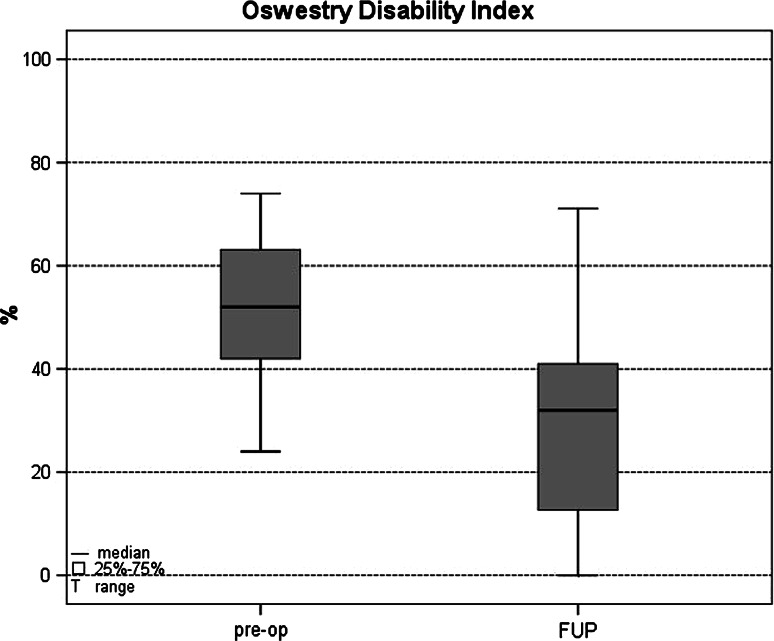

Preoperative mean ODI (51.6 ± 13.2%) dropped significantly to 28.7 ± 18.0% at postoperative follow-up (p < 0.00001) (Fig. 4). On the ODI scale, 19 patients (61.3%) achieved at least a 15%-point improvement, which has been accepted as a clinically significant change by the FDA [12].

Fig. 4.

Oswestry disability index (ODI) results before operation and at mean follow-up time of 39 months (range 24–90 months). These were the values for all 31 patients, including those who had postoperative complications

Surgical outcomes and complications

Solid fusion was achieved in 100% of the segments in which the Dynesys® device was used as a posterior tension band to enhance PLIF.

One patient showed asymptomatic lucency around a screw at L3 requiring no additional surgical intervention. This patient had undergone dynamic stabilization at L3–L4 (Dynesys® only) and fusion at L4–L5. This was the only radiological screw loosening observed. Therefore, only 0.45% of the Dynesys® screws (one out of a total of 222 screws) showed radiographic signs of loosening.

Three patients (9.7%) required surgical reintervention during the study period. One patient had an early seroma, which was surgically treated 15 days postoperatively without removing Dynesys®. Another reoperation was required 44 months after index surgery to extend dynamic stabilization to the two adjacent cranial segments caused by further disc degeneration with disc herniation and instability. In this case, the original construct was Dynesys® only on L3–L4 and fusion on L4–L5. Pedicle screws, spacers, and cage from the original construct were not removed, but the cord was replaced and extended from L1 to L5. The third reoperation was required 8 months after index surgery to extend fusion to the adjacent caudal segment for facet joint arthrosis. In this case, the original procedures were dynamic stabilization at L3–L4 (Dynesys® only) and fusion at L4–L5. This original construct was maintained during revision surgery, and L5–S1 was fused with a PLIF procedure and additional translaminar screw fixation. In addition, another patient suffered from an unrelated osteoporotic fracture requiring no surgical reintervention.

No other adjacent segment degeneration was detected either radiologically or clinically. There was no graft-site problem or pseudoarthrosis.

Discussion

Essential to understanding of DDD are theoretical concepts such as the spinal motion segment [25] or functional spinal unit [52], and the three phases of spinal degeneration proposed by Kirkaldy-Willis and Farfan [29]. Starting from these basic tenets, research has provided valuable information on the degenerating spine and, in turn, DDD. This has culminated in recent work that addresses the aging spine (e.g. natural history [2], inflammatory mediators [39], radiological changes [48], genomic factors [45], hereditary effects [49], and osteoporotic fracture modeling [27]) and specific aspects of the degenerative cascade (e.g. paraspinal muscles in lumbar degenerative kyphosis [26], paraspinal denervation [21]). The relevance of these concepts in the background and development of dynamic stabilization (Dynesys®) has been described previously [44].

Useful reviews of DDD research include a comprehensive clinical review by Bono and Lee [5], an epidemiological review of genetic influences by Battie et al. [1], advances in molecular biology by Guiot and Fessler [20], and advances in imaging studies [24, 34, 37].

The choice of appropriate treatment for any specific patient with DDD is complex. The standard fusion techniques used in this study are widely accepted spine surgical techniques [8, 13, 47, 50]. Fritzell et al. [14] compared different fusion techniques in a prospective randomized study, and they concluded that ALIF and PLIF procedures are inferior to non-instrumented or instrumented postero-lateral fusion (PLF). A closer look at their results reveals a surprisingly high amount of surgical complications in the ALIF/PLIF group (including an operation at the wrong level and an abnormally high neurological complication rate). This suggests that the poor clinical outcome of the ALIF/PLIF group may have been related to factors other than drawbacks intrinsic to these two procedures.

Although in a somewhat heterogeneous population (in terms of indications, levels of surgery, and prior surgeries) of 31 patients operated with Dynesys® by three different surgeons, Grob et al. [19] reported discouraging results. In contrast, a number of other groups have published good clinical outcome showing that Dynesys® as a dynamic stabilization device has been useful across a number of degenerative conditions [40, 41, 43, 46, 51].

Multisegmental disc disease is very often encountered in symptomatic back patients. Spine surgery up to now has always been an either/or solution: surgeons decide either to perform fusion or to apply a non-fusion technique to solve a patient’s problem. The use of either treatment alone at multiple levels in a single-stage operation appears poorly adapted to patients with early degenerative changes in one or more motion segments and advanced changes in others.

In fact, the present author has been using a hybrid technique for over 10 years. The philosophy behind this was to treat the multisegmental diseased lumbar spine segment-by-segment according to the degree of degeneration at each level. Given that a fusion for DDD may eventually affect multiple segments, extending dynamic stabilization to other segments that appear to be involved in the degenerative process and symptomatic to the patient may allow shorter initial arthrodesis constructs, reduce fusion complication risks, and limit reoperations and revisions. More recently, Bertagnoli et al. [3] proposed different combinations of non-fusion and/or fusion techniques to maximize outcomes at each level. To the best of our knowledge, no clinical outcomes have been reported for any type of hybrid constructs for DDD. Cheng et al. [10] compared the biomechanical effect of dynamic stabilization versus fusion in the segment adjacent to a fused segment. They concluded that if posterior fixation is extended to the adjacent level above a circumferential fusion, dynamic stabilization allows significantly more motion than fusion.

One of the first open questions of the hybrid technique applied in this study is whether the combination of Dynesys® and interbody fusion leads to firm fusion. Niosi et al. [35] have described in a biomechanical study that the segmental mobility can be reduced significantly when Dynesys® is applied in a tension band configuration, i.e. when shorter spacers are used. In the present study, the radiological evaluation demonstrated a 100% fusion rate in the segments, where fusion was intended. Table 2 summarizes the fusion rate, percentage of patients who experienced complications, and reoperation rates in the current study compared to other literature on similar patient samples (e.g. diagnosis, fusion method). The present study is only one of three cited studies reporting a 100% fusion rate, albeit in a small sample.

Table 2.

Reported fusion rates, complications and reoperations for similar patient population and fusion techniques

| Research | Sample | Fusion/pseudoarthrosis | Complications | Reoperations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bono and Lee [5] | Comprehensive review of reported fusion for DDD (1979–2000) | Circumferential [PLIF|ALIF + PLF]: 91% fusion (instrumentation not specified) |

Not reported Screw loosening not reported |

Not reported |

| Bono and Lee [6] | Comprehensive review of reported fusion for DDD (1979–2000) by diagnostic subgroup | Fusion overall of unstable DDD [DDDu]: 88% fusion |

Complication rate for unstable DDD [DDDu]: 11% More complications for unstable DDD than stable groups (p < 0.03). Worst clinical outcomes in DDDu group |

Not reported |

| Freeman et al. [13] |

DDD diagnosis in 28/60 (47%) 5.3-year follow-up |

PLIF + PLF: 100% fusion |

All complications: 8/60 = 20% No screw lucencies: 0% |

Not reported |

| Fritzell et al. [14] |

294 patients CLBP|disc degeneration Group III PLIF|ALIF + instrumented PLF (n = 72, only 19 PLIFs) 2-year follow-up |

Instrumented PLIF|ALIF + PLF: 91% fusion |

Screw loosening: 30.6% Major complications: 19.4% for ALIF|PLIFs |

Not reported separately for groups |

| Greiner-Perth et al. [18] |

1,680 cases 360° instrumented PLIF + PLF (Harms Titan cages) 5-year mean follow-up |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF 4.5% pseudoarthrosis [95.5% fusion] |

Implant failure: for 1–2 level fusions: 1.4%; Multisegmental (>2 level) fusions: 0.3% Decompensation of adjacent segments: 2.8% (1–2-level fusions, 2.3%; Multisegmental fusions, 5.1%) Overall reoperation rate: 13.2%, including wound healing problems, 1.5%, recurrent bleeding .2% |

Revision rate: 13.2% (without general risk complications: 11.7%) |

| Hioki et al. [22] |

19 patients with multilevel degenerative lumbar spinal disorders 3.6-year follow-up |

Instrumented PLIF without PLF No pseudoarthrosis reported: 0% (100% fusion) |

All complications: 5/19: 26.3% One displacement of spacer requiring revision Two L3 radiculopathy One pulmonary embolism One symptomatic adjacent-level degeneration No screw lucency reported |

Revision (1/19): 5.3% |

| Kim et al. [28] |

Patients with “degenerative lumbar disease” randomized into three surgery groups, including instrumented PLIF + PLF (1–2 levels, 48 patients) 3-year minimum follow-up |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF group (1–2 levels): 4% pseudoarthrosis (96% fusion) Note careful measurement of lumbar and segmental lordosis |

No significant differences in outcomes for surgical groups PLIF + PLF complications: 19% including two pseudoarthroses No screw loosening reported |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF group (1–2 levels): no revisions |

| Lee et al. [31] | A review of non-union literature | PLIF + PLF: 88–96% fusion (instrumentation not specified) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Madan and Boeree [32] |

Patients with severe LBP (strict exclusion criteria) Instrumented 360° PLIF + PLF (35 patients) versus ALIF (39 patients) 2.4-year follow-up |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF group: fusion in 33 patients (94.3%) |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF group: 4/35 (11.4%) Included two UTIs, one superficial infection, one donor site pain) No screw loosening reported |

Instrumented PLIF + PLF group: none |

| Maghout-Juratli et al. [33] |

1950 patients from Washington State (USA) lumbar fusion outcomes study 56.4% with DDD diagnosis |

PLIF + PLF: fusion rate not specified separately from reoperation | Overall any-postoperative complication rate was 11.8% | |

| Schwarzenbach et al. (present study) | 31 patients with DDD treated with Hybrid combinations of PLIF and Dynesys® used as transpedicular stabilization for fusion and/or dynamic stabilization at adjacent segments | 100% fusion |

Complications related to stabilization: 3/31 (9.8%) One asymptomatic screw loosening (3.3%) One adj. segment instability One adj. facet joint arthrosis Unrelated to stabilization: 2/31 (6.5%), One seroma One unrelated osteoporotic fracture |

Reoperations in 3/31 patients (9.7%): Stabilization-related: One cranial adjacent segment extension of Dynesys® (3.3%) One reoperation for adjacent segment facet arthrosis (3.3%) Operative treatment unrelated to stabilization: One surgery for seroma |

The complication and reoperation rate of the current study is low, demonstrating the functional success of the hybrid construct. Most of the complications and reoperations were attributable to adjacent segments comparable to the observations of Stoll et al. [46]. Schaeren et al. [41] also reported a high rate of adjacent segment degeneration in their patient population after treatment with Dynesys®. This raises the question of whether the well-known problem of adjacent level degeneration next to fusion [15, 16, 53] can be mitigated by introducing the hybrid technique. There is no consensus on the mechanisms of adjacent segment degeneration. Little is known about the ideal biomechanical properties of a posterior dynamic stabilization system. One of the limiting factors of Dynesys® might be that it is too rigid in flexion to fulfill the theoretical demands to protect against adjacent segment deterioration [42]. However, whether the onset of degeneration in adjacent segments can be attributed to the type of instrumentation or to the natural history of the disease cannot be determined to date and is subject to further research.

The small incidence of screw loosening (3.2% of patients; 0.45% of screws) reported in this study is in the lowest range of all studies reporting screw loosening for Dynesys®, either as percentage of patients or as percentage of screws [19, 40, 43, 46, 51].

Tables 2, 3, and 4 include only studies that have reported results for patients with a DDD diagnosis; however, their definitions vary. This attempt to approach a pure diagnostic category has also limited the number of comparisons available for variables such as reoperation rate. Including a definition of DDD involvement in herniated disc, canal stenosis, and degenerative instability, Diwan et al. [11] generalized that 15% of initial lumbar cases for these degenerative conditions require reoperations. The largest series in Table 2 [18], which included a wide range of degenerative conditions, found a reoperation rate of 13.2%. This large study provides possibly the best comparison for revisions at adjacent segments, which was 5.1% for multisegmental fusions (>2 segments) compared to 6.5% in the current multisegmental hybrid sample.

Table 3.

Published back and leg pain scores (VAS) for similar patient population and fusion techniques

| Research | Sample | Preoperative | Postoperative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fritzell et al. [14] |

294 patients CLBP|disc degeneration Group III PLIF|ALIF + instrumented PLF(n = 72, only 19 PLIFs) 2-year follow-up |

Back pain: 6.6 ± 1.5a Leg pain: 3.7 ± 2.8 |

Back pain: 4.6 ± 2.7a Leg pain: 3.2 ± 2.8 |

| Kim et al. [28] |

Patients with “degenerative lumbar disease” randomized into three surgery groups, including instrumented PLIF + PLF (1–2 levels, 48 patients) 3-year minimum follow-up |

Back pain: 7.52 ± 1.16 Leg pain: 6.57 ± 1.31 |

Back pain: 2.23 ± 0.63 Leg pain: 1.46 ± 1.58 |

| Zanoli et al. [54] |

755 patients for development of VAS scale in Swedish lumbar spine registry DDD group: VAS estimated from graph |

Back pain: 6.0 est Leg pain: 6.5 est |

Back pain 12 months: 2.5 est Leg pain 12 months: 3.0 est |

| Schwarzenbach et al. (present study) |

31 patients with DDD treated with Hybrid combinations of PLIF and Dynesys® used as transpedicular stabilization for fusion and/or dynamic stabilization at adjacent segments |

Back pain: 7.3 ± 1.7 Leg pain: 6.0 ± 2.9 |

Back pain: 3.4 ± 2.7 Leg pain: 2.3 ± 2.9 |

aReported scores expressed as 0–10

Table 4.

Published Oswestry disability index (ODI) for similar patient population and fusion techniques

| Research | Sample | Preoperative | Postoperative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freeman et al. [13] |

DDD diagnosis in 28/60 patients (47%) PLIF + instrumented PLF 5.3 years |

79% had postop ODI < 30% | |

| Fritzell et al. [14] |

294 patients CLBP|disc degeneration Group III PLIF|ALIF + instrumented PLF (n = 72, only 19 PLIFs) |

47.3 ± 10.9 | 38.5 ± 18.9 |

| 2-year follow-up | |||

| Glassman et al. [17] | Review of 479 patients outcomes: 360° fusion group | Mean improvement in 360° group | |

| 1 year | 17.9% | ||

| 2 years | 18.9% | ||

| Kim et al. [28] |

Patients with “degenerative lumbar disease” randomized into 3 surgery groups, including instrumented PLIF + PLF (1–2 levels, 48 patients) 3-year follow-up |

59.2 ± 6.9 |

1 year: 21.6 ± 10.5 3 years: 23.9 ± 12.7 |

| Schwarzenbach et al. (present study) | 31 patients with DDD treated with hybrid combinations of PLIF and Dynesys® used as transpedicular stabilization for fusion and/or dynamic stabilization at adjacent segments | 51.6 ± 13.2 |

28.7 ± 18.0 61.3% (n = 19) ≥15% improvement |

Visual analog scale improvements achieved by patients in the present study were compared to other VAS assessments in published studies using similar DDD patient groups and similar fusion techniques (Table 3). This patient sample with hybrid combinations of PLIF and Dynesys® used for both fusion enhancement and dynamic stabilization fell in the upper range of improvements reported for both back pain and leg pain. Kim et al. [28] reported an improvement of 5.5 units in both leg and back pain, while the patients in the present study improved an average of 3.9 units for back pain and 3.7 units for leg pain. Fritzell et al. [14] and Zanoli et al. [54] reported smaller decreases in pain achieved using fusion, the latter study consisting of a large patient sample (n = 755).

Regarding ODI results, the patients in the present study showed improvements that fell toward the high middle range of improvement percentages among similar reported studies (Table 4). The average improvement in the present study was 22.9%. Kim et al. [28] showed the highest average improvement (35.3%, 3 years after surgery), and Fritzell et al. [14] showed the lowest average improvement (8.8%, 2 years after surgery). While many other studies could have been selected as comparisons, these were most similar in diagnosis and fusion/non-fusion treatment to the present sample.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that hybrid segment-by-segment treatment with Dynesys® in combination with interbody fusion is both technically feasible and effective for surgical treatment of multilevel DDD. This study demonstrates the benefits of developing treatment specific for the needs of the patient and each vertebral segment. However, long-term follow-up studies are required for accurate conclusions on the clinical and functional outcome, and reoperation rates of the hybrid technique.

A combination of fusion and non-fusion treatments is likely to become the future method of choice for many applications throughout the spine. Our goal is to provide optimal treatment within the same spine for vertebral segments that appear to vary significantly along the cascade of degeneration. However, clarification is still needed to establish which levels require fusion and which require dynamic stabilization. We anticipate that advances in understanding the spinal degenerative cascade through new research approaches will be the ultimate key to optimal patient selection as well as optimal selection of specific segmental treatments in hybrid constructs.

Conflict of interest statement

O. Schwarzenbach is consultant to Zimmer GmbH and has received project support.

References

- 1.Battié M, Videman T, Parent E. Lumbar disk degeneration: epidemiology and genetic influences. Spine. 2004;29:2679–2690. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146457.83240.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoist M. Natural history of the aging spine. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S86–S89. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertagnoli R, Tropiano P, Zigler J, Karg A, Voigt S. Hybrid constructs. Orthop Clin N Am. 2005;36:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bono CM, Lee CK. Critical analysis of trends in fusion for degenerative disc disease over the past 20 years. Spine. 2004;29:455–463. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000090825.94611.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bono CM, Lee CK. The influence of subdiagnosis on radiographic and clinical outcomes after lumbar fusion for degenerative disc disorders: an analysis of the literature from two decades. Spine. 2005;30:227–234. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000150488.03578.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boos N, Rieder R, Schade V, Spratt K, Semmer N, Aebi M. Volvo award in clinical sciences. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, work perception and psychosocial factors in identifying symptomatic disk herniations. Spine. 1995;20:2613–2625. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brislin B, Vaccaro A. Advances in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Orthop Clin N Am. 2002;33:367–374. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(01)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carragee EJ, Paragioudakis StJ, Khurana S. Lumbar high-intensity zone and discography in subjects without low back problems. Spine. 2000;25:2987–2992. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng BC, Gordon J, Cheng J, Welch WC. Immediate biomechanical effects of lumbar posterior dynamic stabilization above a circumferential fusion. Spine. 2007;32(23):2551–2557. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cdbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diwan AD, Parvartaneni H, Cammisa F. Failed degenerative lumbar spine surgery. Orthop Clin N Am. 2003;34:309–324. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fairbank JCT, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–2953. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman BJC, Licina P, Mehdian SH. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion combined with instrumented postero-lateral fusion: 5-year results in 60 patients. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:42–46. doi: 10.1007/s005860050007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A, Swedish Lumbar Spine Group Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine. 2002;27:1131–1141. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiselli G, Wang JC, Bhatia NN, Hsu WK, Dawson EG. Adjacent segment degeneration in the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillet P. The fate of the adjacent motion segments after lumbar fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(4):338–345. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glassman S, Gornet MF, Branch C, Polly D, Peloza J. MOS short form 36 and Oswestry disability index outcomes in lumbar fusion: a multicenter experience. Spine J. 2006;6:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greiner-Perth R, Boehm H, Allam Y, Elsaghir H, Franke J. Reoperation rate after instrumented posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 2004;29:2516–2520. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144833.63581.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grob D, Benini A, Junge A, Mannion AF. Clinical experience with the Dynesys semirigid fixation system for the lumbar spine: surgical and patient-oriented outcome in 50 cases after an average of 2 years. Spine. 2005;30(3):324–331. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152584.46266.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiot BH, Fessler RG. Molecular biology of degenerative disc disease. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1034–1040. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haig AJ. Paraspinal denervation and the spinal degenerative cascade. Spine J. 2002;2:372–380. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hioki A, Miyamoto K, Kodama H, Hosoe H, Nishimoto H. Two-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative disc disease: improved clinical outcome with restoration of lumbar lordosis. Spine J. 2005;5:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarvik J, Hollingworth W, Haegerty P, Haynor DR, Deyo RA. The longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBack) study: baseline data. Spine. 2001;26:1158–1166. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200105150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayakumar P, Nnadi C, Saifuddin A, MacSweeney E, Casey A. Dynamic degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: diagnosis with axial loaded magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:E298–E301. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216602.98524.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junghanns H. Die gesunde und die kranke Wirbelsäule in Röntgenbild und Klinik. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang CH, Shin MJ, Kim SM, Lee SH, Lee CS. MRI of paraspinal muscles in lumbar degenerative kyphosis patients and control patients with chronic low back pain. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller TS, Harrison DE, Colloca CJ, Harrison DD, Janik TJ. Prediction of osteoporotic spinal deformity. Spine. 2003;28:455–462. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200303010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim KT, Lee SH, Lee YH, Bae SC, Suk KS. Clinical outcomes of 3 fusion methods through the posterior approach in the lumbar spine. Spine. 2006;31:1351–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000218635.14571.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Farfan HF. Instability of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1982;165:110–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjaer P, Ch Leboeuf-Yde, Korsholm L, Sorensen JS, Bendix T. Magnetic resonance imaging and low back pain in adults: a diagnostic imaging study of 40-year-old men and women. Spine. 2005;30:1173–1180. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000162396.97739.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee C, Dorcil J, Radomisli TE. Nonunion of the spine: a review. Clin Orthop. 2004;419:71–75. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madan SS, Boeree NR. Comparison of instrumented anterior interbody fusion with instrumented circumferential lumbar fusion. Eur Spine J. 2003;2:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0516-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maghout-Jurati S, Franklin GM, Mirza SK, Wickizer TM, Fulton-Kehoe D. Lumbar fusion outcomes in Washington State workers’ compensation. Spine. 2006;31:2715–2723. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244589.13674.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masui T, Yukawa Y, Nakamura S, Kajino G, Matsubara Y, Kshiguro N. Natural history of patients with lumbar disc herniation observed by magnetic resonance imaging for minimum 7 years. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:121–126. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000154452.13579.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niosi CA, Zhu QA, Wilson DC, Keynan O, Wilson DR, Oxland TR. Biomechanical characterization of the three-dimensional kinematic behaviour of the Dynesys dynamic stabilization system: an in vitro study. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(6):913–922. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0948-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohlin A, Karlsson M, Düppe H, Hasserius R, Redlund-Johnell I. Complications after transpedicular stabilization of the spine. A survivorship analysis of 163 cases. Spine. 1994;19(24):2774–2779. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pappou IP, Cammisa FP, Girardi FP. Correlation of end plate shape on MRI and disc degeneration in surgically treated patients with degenerative disc disease and herniated nucleus pulposus. Spine J. 2007;7:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2001;26(17):1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podichetty VK. The aging spine: the role of inflammatory mediators in intervertebral disc degeneration. Cell Mol Biol. 2007;53:4–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putzier M, Schneider SV, Funk JF, Tohtz SW, Perka C. The surgical treatment of the lumbar disc prolapse: nucleotomy with additional transpedicular dynamic stabilization versus nucleotomy alone. Spine. 2005;30(5):E109–E114. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154630.79887.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaeren S, Broger I, Jeanneret B. Minimum four-year follow-up of spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis treated with decompression and dynamic stabilization. Spine. 2008;33(18):E636–E642. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817d2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmoelz W, Huber JF, Nydegger T, Claes L, Wilke HJ. Dynamic stabilization of the lumbar spine and its effects on adjacent segments: an in vitro experiment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(4):418–423. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnake KJ, Schaeren S, Jeanneret B. Dynamic stabilization in addition to decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2006;31(4):442–449. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000200092.49001.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarzenbach O, Berlemann U, Stoll TM, Dubois G. Posterior dynamic stabilization systems: Dynesys. Orthop Clin N Am. 2005;36:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solovieva S, Lohiniva J, Leino-Arjas P, Raininko R, Luoma K, Ala-Kokko L, Riihimaki H. Intervertebral disc degeneration in relation to the COL9A3 and the IL-1β gene polymorphisms. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:613–619. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0988-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoll TM, Dubois G, Schwarzenbach O. The dynamic neutralization system for the spine: a multi-center study of a novel non-fusion system. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(Suppl 2):S170–S178. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suk S, Lee CK, Kim WJ, Lee JH, Cho KJ. Adding posterior lumbar interbody fusion to pedicle screw fixation and posterolateral fusion after decompression in spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1997;22:210–219. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199701150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Symmons DP, van Hemert AM, Vandenbroucke JP, Valkenburg HA. A longitudinal study of back pain and radiological changes in the lumbar spines of middle aged women. II. Radiological findings. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:162–166. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Videman T, Battie MC, Ripatti S, Gill K, Manninen H, Kaprio J. Determinants of the progression in lumbar degeneration: a 5-year follow-up of adult male monozygotic twins. Spine. 2006;31(6):671–678. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000202558.86309.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vishteh AG, Crawford NR, Chamberlain RH, Thramann JJ, Park SC. Biomechanical comparison of anterior versus posterior lumbar threaded interbody fusion cages. Spine. 2005;30:302–310. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152155.96919.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welch WC, Cheng BC, Awad TE, Davis R, Maxwell JH, Delamarter R, Wingate JK, Sherman J, Macenski MM. Clinical outcomes of the Dynesys dynamic neutralization system: 1-year preliminary results. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(1):E8. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White AA, Panjabi MM. The basic kinematics of the human spine: a review of past and current knowledge. Spine. 1978;3:12–20. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wimmer C, Gluch H, Krismer M, Ogon M, Jesenko R. AP-translation in the proximal disc adjacent to lumbar spine fusion. A retrospective comparison of mono- and polysegmental fusion in 120 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68(3):269–272. doi: 10.3109/17453679708996699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanoli G, Strömqvist B, Jönsson B. Visual analog scales for interpretation of back and leg pain intensity in patients operated for degenerative lumbar spine disorders. Spine. 2001;26:2375–2380. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]