Abstract

A novel rat model was used to investigate the effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition in posterior spinal fusion augmented with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Nitric oxide (NO) has important physiological functions including the modulation of fracture healing. Recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) enhances spinal fusion. It is not known whether nitric oxide has a role in rhBMP-2 enhanced spinal fusion and remodeling. A novel rat intertransverse fusion model was created using a defined volume of bone graft along with a collagen sponge carrier, which was compacted and delivered using a custom jig. The control groups consisted of a sham group (S, n = 20), an autograft + carrier group (A, n = 28) and a group consisting of 43 μg of rhBMP-2 mixed with autograft + carrier (AB, n = 28). Two experimental groups received a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, N G-nitro l-arginine methyl ester, in a dose of 1 mg/ml ad lib in the drinking water (AL, n = 28) and one of these experimental groups had rhBMP-2 added to the graft mixture at the time of surgery (ALB, n = 28). Rats were killed at 22 and 44 days, spinal columns subjected to radiology, biomechanics and histology. On a radiographic score (0–4) indicating progressive maturation of bone fusion mass, no difference was found between the A and AL groups, however, there was a significant enhancement of fusion when rhBMP-2 was added when compared to the A group (P < 0.001). However, on day 44, the ALB group showed significantly less fusion progression when compared to the AB group (P < 0.01). There was a 25% (P < 0.05) more fusion-mass-area in day 44 of ALB group when compared to day 44 of the AB group indicating that NOS inhibition delayed the remodeling of the fusion mass. Biomechanically, the rhBMP-2 groups were stiffer at all time points compared to the NOS inhibited groups. Decalcified histology demonstrated that there was a delay in graft incorporation whenever NOS was inhibited (AL and ALB groups) as assessed by a 5 point histological maturation score. In a novel model of rat intertransverse process fusion, nitric oxide synthase modulates rhBMP-2 induced corticocancellous autograft incorporation.

Keywords: Spinal fusion, rhBMP-2, Nitric oxide, Nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a short-lived free radical gas produced from l-arginine by the nitric oxide synthases (NOSs). NOS isoforms are either calcium-dependent and constitutively expressed (cNOS) (e.g., neuronal NOS [nNOS] and endothelial NOS [eNOS]) or calcium-independent inducible (iNOS). iNOS is expressed after exposure to diverse stimuli, such as inflammatory cytokines and lipopolysaccharide (LPS); once expressed, the inducible enzyme generates sustained amounts of NO than does the constitutive isoform. We have previously shown that all three isoforms of NOSs are expressed during rat and human fracture healing in a temporal and cell-specific fashion and that the absence of NO leads to impaired fracture healing [1–3].

The bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are growth and differentiation factors that are essential components of the fracture healing cascade [4–6]. Recombinant BMPs have made their way into the clinical arena with recombinant human BMP-2 (INFUSE™; Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc., Memphis, TN, USA) currently being used to augment spinal fusion [7, 8]. Pre-clinical and clinical studies to date have documented the remarkable ability of this protein to form bone [9–12]. Although the role of NO and rhBMP-2 have independently investigated in fracture repair, no study has investigated the role of NO in spinal fusion with and without rhBMP-2.

Materials and methods

l-Nitroso-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Drugs for animal anesthesia and reagent grade organic solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2) was produced by a Chinese hamster ovarian cellular expression system by Genetics Institute (GI., Inc., Andover, MA, USA) and was a gift from Medtronic Sofamor Danek Inc. (Memphis, TN, USA). RhBMP-2 was provided in a freeze-dried form and reconstituted at the time of surgery with MFR buffer (MFR buffer consists of glutamic acid, glycine, and sucrose in injectable H2O) to a 0.43 mg/ml final concentration.

Rat intertransverse fusion model

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Hospital for Special Surgery approved all animal experimentation. Male Sprague–Dawley rats with a mean weight of 345 (range 320–415 g) and an average age of 12 weeks (range 10–14 weeks) were housed under a 12 h day/night light condition with 60% humidity at 21°C. The anesthetic consisted of intraperitoneal administration of ketamine 40–80 mg/kg and xylazine 5–10 mg/kg. Maintenance of anesthesia was performed using oxygen (2 L/min) and halothane via facemask. Monitoring was done by a pulse oximeter placed on the right forelimb. The surgical site was prepped by shaving the entire dorsum free of hair and then scrubbed twice with betadine soap and alternatingly wiped with 70% isopropyl alcohol. 2 ml of 0.5% Marcain was infiltrated over the incision site. Buprenorphine 0.05–0.075 mg/kg, I/M was administered at the end of the procedure. The rats were placed in a water-recirculating heat pad and covered with soft linen until they awoke. The groups of animals undergoing nitric oxide synthase inhibition received an NO inhibitor, N G-nitro l arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) in the dose of 1 mg/ml ad lib in the drinking water starting 2 days preoperatively. At term, animals were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation.

Procurement of bone graft

The bone graft was obtained from the tailbones via caudectomy prior to the exposure of the spine. A dorsal incision was made over the coccyx at (Co)6–10 following which the tail was transected between the caudal vertebrae at Co7. A V-shaped soft tissue flap was preserved for closure with 3–0 absorbable sutures. The transected tail was then dissected via a longitudinal incision. The soft tissue was dissected off using tissue forceps, rongeurs and a scalpel. Consistently, we procured seven tailbone vertebrae and morselized them longitudinally using bone-cutting rongeurs and scissors. The bone graft was weighed to quantify the harvested bone. The average weight of bone graft per rat was 0.44 (range 0.38–0.50 g).

Spinal fusion

After procurement of the bone graft, a 4 cm longitudinal skin incision was made on the dorsal lumbar midline. Following exposure of the dorsolumbar fascia, bilateral muscle splitting incisions were performed to expose the transverse processes. A #15 blade on a scalpel was used to gently scrape the posterior surface of the transverse process to emulate osteoabrasion. After irrigation, the autograft derived from the tail was placed in the defect. After the surgical procedure, the wound was thoroughly lavaged with saline prior to graft placement (deep layer), the fascial layer closed with 4.0 Vicryl in continuous fashion and then the skin was closed (superficial layer) in standard interrupted fashion with 3.0 Proline.

Graft preparation

Using a 2 mm rongeur, the harvested graft was morcellized. Collagen type I (Helistat, Integrated Life Science, Plainsboro, NJ, USA; 1 mm × 2 cm × 1 cm) was cut into uniform 2 mm pieces. The sponge was soaked either in saline or in one ml of rhBMP-2 solution that was drip applied at the time of surgery and then mixed with the graft. To standardize graft density a custom compaction jig was used (Fig. 1.) The plunger was used to deliver the graft to the fusion bed. This helped us optimize graft quantity and density.

Fig. 1.

Custom compaction jig specially designed to standardize autogenous bone graft volume and density for each animal fusion. The jig consisted of three parts: (a) loading device, (b) compactor and (c) plunger. Bone graft was morcelized with a rongeur and then added into the loading device and compacted. The plunger was used to deliver the compacted graft at the fusion bed at surgery

To determine the effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on recombinant human bone morphogenetic-2 induced spinal fusion, four groups underwent spinal fusion while one group had a sham (Group S) operation where exposure of the transverse processes was performed along with a caudectomy but no autograft was harvested or implanted. The four operative groups included autograft alone group (Group A; n = 28), autograft + l-NAME (Group AL; n = 28), autograft + 43 μg rhBMP-2 (Group AB; n = 28) and autograft + l-NAME + 43 μg rhBMP-2 (Group ALB; n = 28). In each group, 14 rats were killed at 21 days and 14 were killed at 44 days (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental groups

| Group | Description |

|---|---|

| S | Sham group |

| A | Autograft group |

| AB | Autograft + rhBMP-2 group |

| AL | Autograft + l -NAME |

| ALB | Autograft + rhBMP-2 + l -NAME |

Sham group (S, n = 20), an autograft + carrier group (A, n = 28) and a group consisting of 43 μg of rhBMP-2 mixed with autograft + carrier (AB, n = 28). Two experimental groups received a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, N G-nitro l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), in a dose of 1 mg/ml ad lib in the drinking water (AL, n = 28) and one of these experimental groups had rhBMP-2 added to the graft mixture at the time of surgery (ALB, n = 28)

Faxitron and image analysis

The lumbar spinal columns were excised with care taken to avoid disturbing the fusion mass. The spinal column was dissected free of soft tissue to provide a clear radiographic image. The specimens were then radiographed in the frontal projection using the Faxitron X-ray apparatus (Model 8050-010; Faxitron X-ray Corporation; Wheeling, IL, USA). For optimal observation of autograft resorption, bony continuity, and new bone formation, the specimens were exposed for 8 min at 50 kVp. A aluminum step ladder control was used as an internal control for intensity as previously described. It also helped in maintaining the aspect ratio of subsequent images and their distance calibration. For analysis, the radiographs were digitized using a digital camera (Kodak DCS-420c) with a resolution of 1,524 × 1,012 pixels. Analysis of the faxitron images was performed as follows.

Radiographic fusion score (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Five point radiographic grading score (0–4) to evaluate maturation of fusion on faxitron analysis. Increasing score denotes maturation of the fusion mass

Radiographs were quantified using a 5-point (0–4) fusion score by two blinded observers as follows: 0 = no bone, 1 = evidence of resorption with sclerosis and increased intertransverse density, 2 = evidence of autograft resorption with less than 25% intertransverse area consisting of bridging trabeculae, 3 = evidence of resorption and remodeling with up to 50% intertransverse area consisting of bridging trabeculae, 4 = clearly defined external bony cortex with greater than 75% intertransverse area consisting of bridging trabeculae.

Fusion mass area

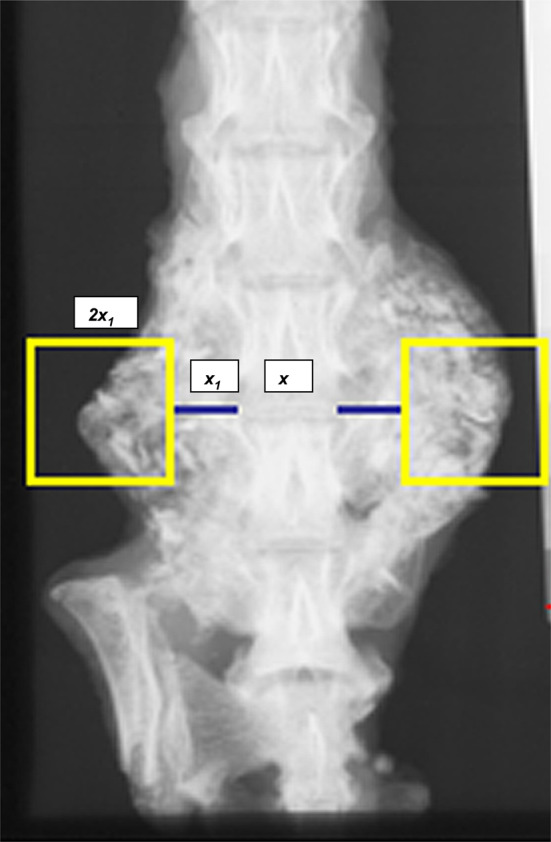

Using Metamorph Image Analysis and Processing System (Universal Imaging Co, Downington, PA, USA, Version 4.0) computer program, fusion masses on each radiograph were outlined and the total fusion mass area in square mm was calculated bilaterally. In order to further analyze the fusion mass area, a square region-of-interest (SROI) was constructed bilaterally. Briefly, for each faxitron, the length and width of the L4 vertebra was measured and normalized with the height and width of the aluminum stepladder control. The length of the L4–L5 intervertebral disc was measured (x) on each faxitron and an equidistant line (x 1) was drawn bilaterally from the lateral most edges of the L4–L5 intervertebral disc into the fusion masses. Bilateral square regions of interest (ROI) with the dimensions of 2 x 1 were constructed, with the equidistant line x 1 bisecting the medial border of the square. Fusion mass area contained within the ROI was calculated in square mm (Fig. 3) with the Metamorph system. This method insured a consistent, reproducible, and reliable assessment of the fusion masses within each group.

Fig. 3.

Construction of a square region-of-interest (SROI). x length of L4–L5 intervertebral disc on posteroanterior faxitron as computed by Metamorph Image analysis. x 1 Equidistant line drawn bilaterally from lateral margin of the L4–L5 intervertebral disc projecting into the fusion masses on either side. 2x 1 Square with dimensions of 2x 1. Fusion mass contained within the SROI was calculated bilaterally using Metamorph Image analysis for each group at both time points

Biomechanics

Manual palpation for fusion

Manual dissection of explanted specimens was performed, leaving intact the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, interspinous ligaments, and intervertebral disks. The qualitative evaluation performed by three blinded observers involved the manipulation of the L-4 and L-5 level and examination of any relative motion between L-4 and L-5. These samples were then used for biomechanical testing as described below.

Biomechanical testing

The L4–L5 fusion mass was cleaned of soft tissue as completely as possible without disturbing the fusion mass. Spines were then potted at one end in epoxy (Bondo®), allowing the potting to rise only to a point on the body of the inferior fusion level (L4) where no articular elements were included in the potting.

Potted specimens were fixed to a novel mechanical testing device (MTD) developed at the Biomechanics Laboratory at The Hospital for Special Surgery, by securing the potted end to the device and attaching an alligator clip firmly to the spinous process of the superior fusion level (L5) (Fig. 4). The potted end of the specimen rode on a linear bearing that allowed freedom of motion in the superior and inferior direction. The MTD consisted of a manual operator-controlled displacer that cyclically loaded the fusion level through the spinous process in flexion and extension to maximum forces of +1.5 N and −1.5 N. The forces were measured by a load cell (Sensotec model 31) and the displacement was measured by a linear variable differential transducer (Sensotec model M5M5H). All specimens were cycled for 120 s, with the forces and displacements recorded at a rate of 10 Hz using Labtech Notebookpro (version 8.1). The data were then assessed, and one cycle of representative, consistent, and overlapping data was extracted. The range of motion (mm) and hysteresis (N × mm) were calculated for this cycle.

Fig. 4.

Mechanical Testing Device (MTD). Schematic diagram of the device and setup for testing range of motion and hysteresis

Histology

A separate set of animals were used for histologic analysis. Spinal motion segments were fixed for 24 h in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then decalcified in 5% nitric oxide for 4 days. After decalcification, specimens were sectioned in the mid sagittal plane and sequentially dehydrated in 95% alcohol for 2 days, 2 changes of 100% alcohol for 2 days and finally cleared in xylene for 1 day. Thereafter, specimens were paraffin embedded and sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm. The slides were stained using hematoxylin and eosin and Goldner’s trichrome as previously described. Numbered consecutive sections were stained with number-matched stains. Sections were studied under a light microscope and images were recorded and analyzed for percentage area of fibrous tissue and cartilage and bony tissue using Metamorph Image Analysis and Processing System (Universal Imaging Co, Downington, PA, USA, Version 4.0) computer program. The fusion segment was studied in three areas: (a) transverse process-fusion mass area 1 (TP-FM 1) that corresponded with the proximal (L4) transverse process, (b) fusion mass center (FMC) that corresponded to the area in between the transverse processes and (c) transverse process-fusion mass area 2 (TP-FM 2) that corresponded to the distal (L5) transverse process (Fig. 5). Each segment was scored using a 5 point score as follows: 0 = no bony contiguity between graft and transverse processes, 1 = abundant fibrous tissue with segments of dead unremodeled bone graft, 2 = some bony contiguity with moderate fibrous tissue, no marrow channels, 3 = bony contiguity with marrow channels, some fibrous tissue and 4 = bone on bone, consolidated fusion with bony contiguity and marrow channels. The transverse process-fusion mass interface scores for each section were then combined and an average value calculated. The fusion mass center was specifically analyzed for percent area of fibrous tissue as an index of fusion mass maturity by Metamorph Image analysis.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of histological key utilized in scoring five groups (S sham group, A autograft group, AL l-NAME group, AB rhBMP-2 group, ALB l-NAME + rhBMP-2 group) at 21 and 44 days. TP-FM 1 = transverse process + fusion mass interface area 1 (most proximal); TP-FM 2 = transverse process + fusion mass interface 2 (most distal) and FMC = fusion mass centre. Histological score was developed as follows: 0 = no bony contiguity between graft and transverse processes, 1 = abundant fibrous tissue with segments of dead unremodeled bone graft, 2 = some bony contiguity with moderate fibrous tissue, no marrow channels, 3 = bony contiguity with marrow channels, some fibrous tissue and 4 = bone on bone, consolidated fusion with bony contiguity and marrow channels

Statistical analysis

All observations are reported as average (±SEM). Unpaired Student’s t test was applied to compare bone between the autograft and rhBMP-2 treated groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare data between groups. A statistically significant observation was reported when P ≤ 0.05.

Results

The autograft + rhBMP-2 (AB) group had greater volume of fusion mass on gross inspection than all other groups. Average radiographic fusion scores in the AB group were significantly higher compared to the autograft (A) alone group at 3 weeks (3.3 vs. 1.0, P < 0.001) and 6 weeks (4.0 vs. 2.0, P < 0.001). In the experimental group treated with autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 (ALB), radiographic fusion scores, though higher than the autograft alone (A) group at both time points, lagged behind the autograft + rhBMP-2 group, a difference that was significant at 6 weeks (AB: 4.0 vs. ALB: 3.2, P < 0.001). Total fusion mass area was significantly higher for the AB group at 3 weeks compared with all other groups (P < 0.001). However, at 6 weeks, the total fusion mass area in the autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 (ALB) group was significantly greater than in the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (P < 0.05). Further analysis of the radiographic fusion mass by the square region-of-interest (SROI) method mirrored the results of the total fusion mass area. Fusion mass area in the SROI was significantly greater at 3 weeks for the autograft + rhBMP-2 group in comparison with all other groups (P < 0.05). However, the fusion mass area in the experimental ALB group was significantly greater than any other group at 6 weeks (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Radiographic and biomechanical analysis of rat intertransverse process spinal fusion

| Parameters | S | A | AL | AB | ALB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographic fusion score | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2* | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| 0 ± 0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0 | 4.0 ± 0* | 3.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Total fusion mass area (mm2) | 0 ± 0 | 163 ± 10 | 190 ± 12 | 266 ± 15* | 230 ± 11 |

| 0 ± 0 | 167 ± 14 | 192 ± 6.0 | 225 ± 17 | 297 ± 26 + | |

| Fusion mass in SROI (mm2) | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 25.3 ± 3.0 | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 45.0 ± 3.0* | 35.0 ± 3.0 |

| 4.3 ± 1.0 | 26.0 ± 5.0 | 30.0 ± 2.0 | 27.0 ± 4.0 | 45.0 ± 4.0 + | |

| Manual palpation for fusion (%) | 0 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 80 |

| 0 | 70 | 33 | 100 | 71+ | |

| Range of motion (mm) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.5 ± 0.1** | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0 | |

| Hysteresis (N mm) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0 | 1 ± 0.2 |

| 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3** | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

Mean ± SE (n = 28/group). Upper figures in columns = 21 days, lower figures = 44 days.

SROI square region of interest, S sham, A autograft, AL autograft + l-NAME, AB autograft = rhBMP-2, ALB autograft + rhBMP-2 + l-NAME

* AB/A, P < 0.001, ** AL/A, P < 0.05, + ALB/AB, P < 0.05

Manual palpation yielded fusion rates of 100% for the autograft + rhBMP-2 (AB) group at both 3 and 6 weeks. Autograft alone group (A) fused at a 50% rate at 3 weeks that went up to a 70% fusion rate at 6 weeks. In contrast, the autograft + l-NAME treated group (AL) could only achieve a 33% fusion rate at 6 weeks. In contrast, the experimental autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 group (ALB) had an 80% fusion rate at 3 weeks and a 71% fusion rate at 6 weeks compared to the 100% fusions achieved by the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (AB) at both time points. Utilizing the mechanical testing device (MTD) to quantify range of motion after −1.5 to 1.5 N force, the sham-operated group (S) had the greatest range of motion at both time points. At 3 weeks, the least range of motion was observed in the autograft + rhBMP-2 (AB) group when compared to the rest of the groups. At 6 weeks, however, although least range of motion was demonstrated in both the rhBMP-2 treated groups (AB and ALB), the autograft + l-NAME group (AL) had the greatest range of motion (P < 0.05). These results were similar to the manual palpation results. Hysteresis (N*mm) is a measure of energy dissipated during a loading cycle. Autograft + rhBMP-2 (AB) had the lowest hysteresis at both time points group indicating compact solid fusions, compared to the rest of the groups, a difference that was significant at 6 weeks between the AB group and the AL group. The experimental group, autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 (ALB) had hysteresis results greater than the AB group at both time points although this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Gross histological evaluation of the fusion mass sections was consistent with the radiographic findings. Specimens from the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (AB) revealed abundant amounts of osteoid, larger cortical rims and more mature fusions than specimens from the other three groups. Specifically, the fusion masses were larger, with more mature fusions as evidenced by more osteoblast-lined trabeculae and less cartilage. The autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 (ALB) group revealed larger areas of unremodeled autograft in a fusion bed clearly less mature than the AB group. The average transverse process-fusion mass interface scores were the highest for the autograft + rhBMP-2 (AB) group at 3 and 6 weeks when compared to the rest of the groups (P < 0.001). The experimental autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 (ALB) group had 3 and 6-week interface scores that were significantly higher than the sham group (S), the autograft alone group (A) and the l-NAME treated group (L) (P < 0.05). However, at both time points, the interface scores of the ALB group were significantly less than the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (AB; P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Similarly, analysis of the fusion mass center revealed significantly lower percentage of fibrous tissue in the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (AB) compared to the other groups at 3 and 6 weeks (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7). Bone tissue within the centrum of the fusion mass was estimated with the Metamorph Image analysis system as a measure of bony consolidation and remodeling. With time, the fusion mass size decreases with continuous remodeling and resorption. There was a significant difference in bone contained within the fusion mass centre when comparing the autograft + rhBMP-2 group (AB) with the experimental autograft + l-NAME + rhBMP-2 group (ALB) at 3 weeks (P < 0.001) and at 6 weeks (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Bar graph showing histologic scores (as scored by the 5-point histologic grading score described in Fig. 5. S sham, A autograft, AL autograft + l-NAME, AB autograft = rhBMP-2, ALB autograft + rhBMP-2 + l-NAME) Average (±SEM) scores reported at 21 and 44 days. ***P < 0.001 as estimated by Student’s t test

Fig. 7.

Bar graph showing percent average (±SEM) fibrous tissue within the centrum of the fusion mass reported at 21 and 44 days. This was used as an index of maturity of the fusion mass between groups. S sham, A autograft, AL autograft + l-NAME, AB autograft = rhBMP-2, ALB autograft + rhBMP-2 + l-NAME ***P < 0.001 as estimated by Student’s t test

Discussion

Our study has examined the role of the gaseous molecule, nitric oxide (NO) in a novel method of rat intertransverse process fusion and examined its modulation of a known bone morphogen, rhBMP-2. Previous studies have investigated the role of specific protein growth factors in fusion in rat posterolateral fusion models; however, either autogenous bone graft harvested from the iliac crest has been used in these studies or other variations of carriers have been used [13–18]. Our model differs in that by utilizing a specific number of rat-tail bones, we were able to standardize the bone graft weight and density with the use of a custom jig prior to implanting in the posterolateral gutters. Decortication was obtained by the use of osteoabrasion with a scalpel. Similarly, biomechanical analysis of rat spinal fusion with a linear variable differential transducer (LVDT) has not previously been described. Utilizing these methods, we have obtained a 70% fusion rate in our autogenous bone alone control animals. This fusion rate compares favorably with the standard rabbit model of posterolateral intertransverse fusion [19].

Most bone cells can be induced to produce iNOS in response to stimulation with cytokines and/or endotoxin by mechanical stimulation or by creation of a fracture [1–3]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibition has been shown to impair fracture repair [1]. Similar inhibition was demonstrated with spinal fusion in our study. There was five times more range of motion in the group treated with the NOS-inhibitor versus the autogenous bone graft alone control at 6 weeks. Sustained iNOS inhibition up to 6 weeks led to an eventual 33% fusion rate by manual palpation. Treatment with rhBMP-2 alone led to 100% fusion in this model. These results are compatible with the abundant pre-clinical literature. Interestingly, use of rhBMP-2 alone accelerated the healing environment with 100% fusion detected at 3 weeks after surgery in our model. When examining the effect of NOS inhibition on rhBMP-2 induced spinal fusion, we found that there was a 30% decrease in segmental stiffness by manual palpation between the NOS inhibited rhBMP-2 group versus the rhBMP-2 alone group. Similarly, there were poorer histologic interface scores and higher fibrous tissue content in the NOS inhibited rhBMP-2 group versus the rhBMP-2 alone group at 3 and 6 weeks.

There are several limitations associated with this work. We did not have an experimental group of animals in which the synthesis of nitric oxide was stimulated by adding a direct NO donor at the fusion bed site. Adding this group would allow direct comparison of NO supplemented versus NO inhibited spinal fusion. Similarly, we did not have group of animal where we delayed the administration of the NOS inhibitor until after the initial stage of inflammation to see if indeed remodeling of the spinal fusion mass was inhibited by the temporal absence of nitric oxide, specific to its actions on bone healing and remodeling. Several different doses of l-NAME (NOS inhibition) at various time points would have enabled us to target specifically the defect along the healing cascade. Finally, using a NO knockout mouse model of spinal fusion with and without rhBMP-2 would have strengthened our conclusions.

Three stages of healing in the posterolateral spinal fusion environment have previously been described [20]. They are (1) inflammatory (2) reparative and (3) remodeling. It is likely that signaling molecules that are released during the initial inflammatory phase have the capacity to modulate the cascade of cellular events that are critical to spinal fusion and NO may play an important role as a mediator of the initial inflammatory cascade. Inhibition of NO in the key inflammatory phase may explain the eventual failure of fusion and progression to the next phases of healing. This is evidenced by the increased total fusion mass area data when comparing autogenous bone graft control versus NOS inhibition group. This increased fusion mass area represents unremodeled autogenous bone graft. A similar effect may be attributed to the NOS inhibited rhBMP-2 group versus the rhBMP-2 alone group. One possible explanation of this may be that NO inhibition blunted the powerful rhBMP-2 induced initial inflammatory cascade so critical in the recruitment of progenitor cells and osteoblasts at the fusion site. Increase in the total fusion mass area and a 30% decrease in the fusion rate by manual palpation at 6 weeks points to a decrease in osteoclastic function during the reparative and remodeling phase. Studies by Jung et al. [21] demonstrate a role for NOS in inflammatory bone resorption as well as osteoclast development and activity, in vitro. In an in vivo murine model of inflammatory bone resorption, NOS −/− mice demonstrated a significantly attenuated osteoclast response compared to wild type control, suggesting a defect in osteoclast development or activity. Taken together, these data may point toward NO having a key role in rhBMP-2 induced osteoclastic activity in spinal fusion. However, these effects may be part of a multifold cascade of events and will require future investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Deirdre Campbell D.Eng, Russel Nord, BS, Micheal Peterkin, BS and Steven B. Doty, PhD for their invaluable assistance in the completion of this project.

References

- 1.Diwan AD, Wang MX, Jang D, et al. Nitric oxide modulates fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(2):342–351. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu W, Diwan AD, Lin JH, et al. Nitric oxide synthase isoforms during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(3):535–540. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu W, Murrell GA, Lin JH, et al. Localization of nitric oxide synthases during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(8):1470–1477. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.8.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuji K, Bandyopadhyay A, Harfe BD, et al. BMP2 activity, although dispensable for bone formation, is required for the initiation of fracture healing. Nat Genet. 2006;38(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1038/ng1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murnaghan M, McIlmurray L, Mushipe M, et al. Time for treating bone fracture using rhBMP-2: a randomised placebo controlled mouse fracture trial. J Orthop Res. 2005;23(3):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumner DR, Turner TM, Urban RM, et al. Locally delivered rhBMP-2 enhances bone ingrowth and gap healing in a canine model. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haid RW, Jr, Branch CL, Jr, Alexander JT, et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2 with cylindrical interbody cages. Spine J. 2004;4(5):527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkus JK, Sandhu HS, Gornet MF, et al. Use of rhBMP-2 in combination with structural cortical allografts: clinical and radiographic outcomes in anterior lumbar spinal surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1205–1212. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jone AL, Buchholtz RW, Bosse MJ, et al. Recombinant human BMP-2 and allograft compared with autogenous bone graft for reconstruction of diaphyseal tibial fractures with cortical defects. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(7):1431–1441. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh K, Smucker JD, Boden SD, et al. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 as an adjunct in posterolateral lumbar spine fusion: a prospective CT-scan analysis at one and two years. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(6):416–423. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morisue H, Matsimoto M, Chiba K, et al. A novel hydroxyapatite fiber mesh as a carrier for recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 enhances bone union in rat posterolateral fusion model. Spine. 2006;31(11):1194–1200. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217679.46489.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlisle E, Fischgrund JS. Bone morphogenetic proteins for spinal fusion. Spine J. 2005;5(6 Suppl):240S–249S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grauer JN, Bomback DA, Lugo R, et al. Posterolateral lumbar fusions in athymic rats: characterization of a model. Spine J. 2004;4(3):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu W, Rawlins BA, Boachie-Adjei O, et al. Combined bone morphogenetic protein-2 and -7 gene transfer enhances osteoblastic differentiation and spine fusion in a rodent model. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(12):2021–2032. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salamon ML, Althausen PL, Gupta MC, et al. The effects of BMP-7 in a rat posterolateral intertransverse process fusion model. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):90–95. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bomback DA, Grauer JN, Lugo R, et al. Comparison of posterolateral lumbar fusion rates of Grafton Putty and OP-1 Putty in an athymic rat model. Spine. 2004;29(15):1612–1617. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000132512.53305.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden SD, Titus L, Hair G, et al. Lumbar spine fusion by local gene therapy with cDNA encoding a novel osteoinductive protein (LMP-1) Spine. 1998;23:2486–2492. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JC, Davies M, Kanim LEA, Ukatu CJ, Dawson EG, Lieberman JR (2000) Prospective comparison of commercially available demineralized bone matrix for spine fusion. Paper presented at North American Spine Society Meeting; October 25–28, 2000, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 19.Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC, et al. An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model. Radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine. 1995;20(4):412–420. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boden SD (2002) Overview of the biology of lumbar spine fusion and principles for selecting a bone graft substitute. Spine 27(16 Suppl 1):S26–S31 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jung JY, Lin AC, Ramos LM, et al. Nitric oxide synthase I mediates osteoclast activity in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89(3):613–621. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]