Abstract

This study presents direct experimental evidence for assessing the electrostatic and nonelectrostatic contributions of proteoglycans to the compressive equilibrium modulus of bovine articular cartilage. Immature and mature bovine cartilage samples were tested in unconfined compression and their depth-dependent equilibrium compressive modulus was determined using strain measurements with digital image correlation analysis. The electrostatic contribution was assessed by testing samples in isotonic and hypertonic saline; the combined contribution was assessed by testing untreated and proteoglycan-depleted samples.

Though it is well recognized that proteoglycans contribute significantly to the compressive stiffness of cartilage, results demonstrate that the combined electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions may add up to more than 98% of the modulus, a magnitude not previously appreciated. Of this contribution, about two-thirds arises from electrostatic effects. The compressive modulus of the proteoglycan-depleted cartilage matrix may be as low as 3 kPa, representing less than 2% of the normal tissue modulus; experimental evidence also confirms that the collagen matrix in digested cartilage may buckle under compressive strains, resulting in crimping patterns. Thus, it is reasonable to model the collagen as a fibrillar matrix that can only sustain tension. This study also demonstrates that residual stresses in cartilage do not arise exclusively from proteoglycans, since cartilage remains curled relative to its in situ geometry even after proteoglycan depletion. These increased insights into the structure-function relationships of cartilage can lead to improved constitutive models and a better understanding of the response of cartilage to physiological loading conditions.

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that proteoglycans (PGs) contribute significantly to the compressive modulus of articular cartilage (Maroudas, 1979). However, a precise quantitative assessment of this contribution has yet to be reported. Articular cartilage is mostly comprised of water (60-85% by wet weight), type II collagen (15-22% by wet weight), and PGs known as aggrecan (5-10% by wet weight) (Maroudas, 1979; Mow, 2005). Aggrecans are macromolecules consisting of a main protein core with laterally covalently attached glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, the main GAG types being chondroitin sulfate and, to a lesser extent, keratan sulfate (Muir, 1980).

Many of the studies available in the literature that have used various treatment options to digest the solid matrix have examined only partially digested or degraded tissue (Bader and Kempson, 1994; Basalo et al., 2004; Basalo et al., 2005; Bonassar et al., 1995; Harris et al., 1972; Lotke and Granda, 1972; Lyyra et al., 1999b). While these studies are valuable to the understanding of such pathologies as osteoarthritis, where PG degradation is known to occur, (Carney et al., 1984; McDevitt and Muir, 1976; Muir, 1977), from a basic physics standpoint it is also important to understand the exact contribution each constituent of the solid matrix makes to the overall properties of the tissue.

Experiments have shown that the digestion of proteoglycans with chondroitinase ABC or streptomyces hyaluronidase results in a significant reduction of the equilibrium compressive modulus of articular cartilage (Korhonen et al., 2003; Lyyra et al., 1999a; Nieminen et al., 2000; Rieppo et al., 2003; Toyras et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 1993). Unfortunately, few selective enzymatic digestion studies have quantified the changes in modulus and PG content simultaneously. Zhu et al. (Zhu et al., 1993) have observed a reduction of the compressive Young's modulus by approximately 70% when the PG content was reduced by approximately 80%.

The fixed negative charges of PGs induce a Donnan osmotic pressurization of the tissue's interstitial fluid (Eisenberg and Grodzinsky, 1985; Lai et al., 1991; Maroudas, 1979; Overbeek, 1956) that contributes significantly to its compressive modulus according to theory (Ateshian et al., 2004; Azeloglu et al., 2007). This electrostatic contribution has been supported by the finding that cartilage becomes softer in bathing environments of increasing ionic strengths (Chahine et al., 2004; Eisenberg and Grodzinsky, 1985; Elmore et al., 1963; Maroudas, 1975; Parsons and Black, 1979; Sokoloff, 1963). In particular, Eisenberg and Grodzinsky (Eisenberg and Grodzinsky, 1985) have shown that the equilibrium compressive modulus of articular cartilage decreases from 0.55 MPa at 0.15 M NaCl, to 0.27 MPa at 1.0 M NaCl, suggesting that the contribution from Donnan osmotic pressure under isotonic conditions represents ~50% of the total tissue stiffness. Similarly, Chahine et al. (Chahine et al., 2004) have shown that the Donnan pressure contributes ~60% of the total tissue stiffness, when comparing compressive equilibrium moduli at 0.15 M and 2 M NaCl.

Examination of these literature results suggests that the Donnan osmotic pressure induced by the negatively charged GAGs does not account for the total contribution of PGs to the compressive modulus, since the reduction in compressive stiffness observed with partial PG digestion is greater than that achieved by neutralizing charge (and thus, Donnan) effects. Indeed, direct measurements of the osmotic pressure of chondroitin sulfate solutions in various ionic strengths of NaCl demonstrate that there exists a non-Donnan contribution to the osmotic pressure, of significant magnitude, believed to result from the configurational entropy of GAG molecules (Chahine et al., 2005; Ehrlich et al., 1998). The first aim of this study is to determine this non-Donnan contribution experimentally in situ, by comparing measurements of the equilibrium compressive modulus of articular cartilage in isotonic and hypertonic NaCl, before and after nearly complete digestion of PGs. The PG digestion protocol described by Schmidt et al. (Schmidt et al., 1990) is employed, which has been shown to remove most of the initial PG content, while preserving the collagen content.

Recent advances in the constitutive modeling of articular cartilage have placed an emphasis on modeling the fibrillar nature of the collagen matrix, idealizing it as a material that can only sustain tension (Ateshian et al., 2009; Korhonen et al., 2003; Soltz and Ateshian, 2000; Soulhat et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2007). In these fiber-reinforced models of cartilage, the PGs are generally assumed to represent the ground matrix. A corollary aim of this study is to determine whether a cartilage matrix depleted of all its PGs exhibits a negligible compressive modulus compared to the normal tissue, to help ascertain the validity of the basic constitutive assumption that collagen fibers contribute only to the tensile response.

To further elucidate the potential interaction of zonal variations in PG content with treatment and bathing environment, measurements of the depth-dependent compressive properties are performed across the thickness of the articular layer. Finally, since PG content and depth-dependent properties may vary with age (Williamson et al., 2001), experiments are performed on mature and immature bovine cartilage to determine whether age-related differences may increase our insight into these phenomena.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Details regarding materials and methods are provided in the Supplementary Data (Appendix A). Briefly, six cartilage specimens were harvested each from immature and mature bovine humeral heads for mechanical testing and biochemical analysis; additional specimens were used for histology. Cylindrical disks were sub-punched and the outer ring used for biochemical analysis. Each disk and its outer ring was cut in half and one half was digested of its proteoglycan content using the protocol of Schmidt et al. (Schmidt et al., 1990), thus producing two treatment groups (untreated and digested) for each tissue source (immature and mature). Each half-disk was used for mechanical testing in 0.15 M (isotonic) and 2 M (hypertonic) NaCl, to obtain equilibrium depth-dependent strain measurements at multiple prescribed platen-to-platen engineering strains of 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 14%, and 20%. The equilibrium stress was calculated from the measured load and initial cross-sectional area. The incremental Young's modulus was calculated from the slope of the stress-strain response, at each prescribed nominal compressive strain, and at all points through the depth. The apparent Young's modulus over the full thickness of the sample was calculated from the slope of the applied stress versus engineering strain. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the apparent Young's modulus to examine the effects of treatment (untreated and digested) and bathing environment (isotonic and hypertonic), for each joint age (immature and mature).

The superficial, middle and deep zones were identified from polarized light microscopy measurements reported in our previous study (Canal et al., 2008). The depth-dependent incremental Young's moduli were averaged within each zone, at each nominal platen-to-platen applied strain, to produce three groups for the factor of depth. Two-way ANOVA was performed to examine the effects of depth and applied strain for each combination of joint age (immature and mature), treatment (untreated and digested) and bathing environment (isotonic and hypertonic).

RESULTS

The serial digestion dissected away 97.7% of PGs from the immature tissue and 90.4% from the mature specimens, both representing a significant depletion of PG content (Figure 1). There was also a significant increase in water content per wet weight in the immature samples (p<0.0001), and collagen content per wet weight in the mature samples (p<0.01). Histology comparing an undigested and digested immature sample shows an even depletion of PG (Figure 2). Digested mature samples still showed noticeable curling (Figure 3). In addition, digested mature samples exhibited crimping in the deep zone upon compressive loading, usually immediately below the middle zone (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Proteoglycan (PG), collagen and water as a percentage of wet weight for the four sample groups, immature untreated, immature digested, mature untreated and mature digested. (* p<0.005)

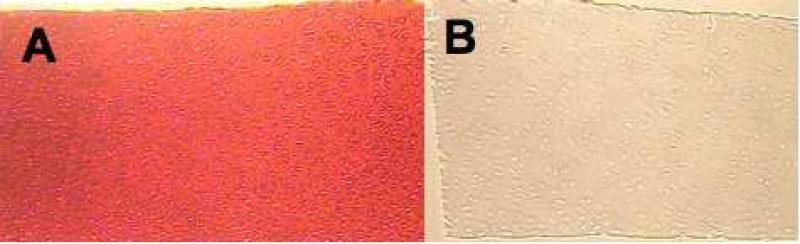

Figure 2.

Safranin O staining of untreated (A) and digested (B) immature cartilage samples showing uniform depletion of PG content through the depth.

Figure 3.

Curling exhibited in PG depleted mature samples. SZ = superficial zone, DZ = deep zone.

Figure 4.

Sequential compression (0 - 6%) of a mature digested sample. Thin white lines indicate delineations between superficial, middle and deep zones as determined from polarized light microscopy on other, age-matched samples. Arrows indicate areas of visible crimping in the solid matrix.

The thickness of untreated and digested samples, as measured after sample preparation and just prior to testing, is summarized in Table 1. The thickness of tissue samples prior to digestion was not recorded for these specimens, but preliminary studies on the digestion protocol employed here, using bovine cartilage samples from a similar source, demonstrated a significant but small decrease in the thickness following digestion (1.15±0.07 mm versus 1.11±0.07, n=9, p<0.001, paired two-tailed t-test, α=0.05). A paired comparison (two-tailed t-test, α=0.05) of each group of specimens between 0.15 M and 2 M showed that the thickness was statistically lower in the hypertonic bath only for immature untreated samples (p<0.005), whereas immature treated (p=0.09), mature untreated (p=0.14) and mature treated (p=0.36) samples showed no significant change with bath osmolarity.

Table 1.

Thickness of cartilage samples prior to mechanical testing (mean±standard deviation, in units of mm).

| Immature | Mature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Digested | Native | Digested | ||||

| 0.15M | 2M | 0.15M | 2M | 0.15M | 2M | 0.15M | 2M |

| 1.16±0.15 | 1.10±0.14 | 0.99±0.15 | 1.03±0.16 | 0.73±0.19 | 0.69±0.16 | 0.73±0.10 | 0.75±0.08 |

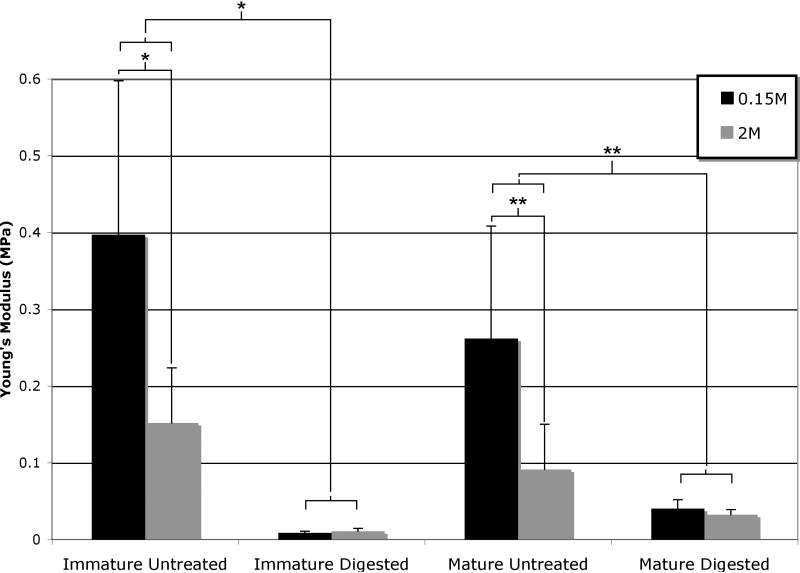

At 20% nominal compressive strain, the apparent equilibrium Young's modulus of the digested samples was significantly lower than that of the untreated tissue in both immature and mature sample groups (p<0.0001, Figure 5). In 0.15 M NaCl, the modulus reduced by approximately 98% and 85% in immature and mature samples, respectively. The decrease in apparent equilibrium Young's modulus of the undigested samples when tested in 2M solution as compared with 0.15M solution was approximately 62% for the immature sample group and 65% for the mature sample groups (Figure 5). No significant change was observed with increased NaCl tonicity in the digested sample groups (p=0.10).

Figure 5.

Summary of the apparent compressive Young's modulus, evaluated from the slope of the stress versus engineering strain, for all sample groups at both 0.15M and 2M bath concentrations; *p<.0001 and **p<0.01.

From a previous study (Canal et al., 2008), it was determined that the superficial and middle zones respectively occupy 4.6±1.0% and 12.1±2.3% of the articular layer thickness in immature joints, and 6.5±1.4% and 17.0±1.5% in mature joints. Incremental Young's moduli for these zones are shown for both untreated and digested samples in 0.15M and 2M NaCl for both immature (Figure 6) and mature (Figure 7) tissue. Using a two-way ANOVA for the factors of depth and applied strain within each treatment group (immature and mature, native and digested, isotonic and hypertonic), the zone-averaged incremental moduli were significantly higher in the deep zone than in the middle and superficial zones for all treatment groups of immature samples (p<0.0001 for native isotonic, native hypertonic, and digested isotonic; p<0.02 for digested hypertonic), and two of the four treatment groups of mature samples (p<0.03 for native isotonic and digested hypertonic). The incremental modulus decreased with applied strain in the range of small strains in immature native isotonic (p<0.003) and hypertonic (p<0.0001) groups, and in mature digested isotonic (p<0.003) and hypertonic (p<0.004) groups. At higher applied strains a more homogeneous incremental modulus was exhibited through the depth due to apparent stiffening of the superficial zone and softening of the deep zone.

Figure 6.

Incremental Young's moduli for immature sample groups over the applied strain range shown for both untreated (top, n=6) and digested (bottom, n=6) tested in 0.15M (left) and 2M (right) solutions. (Note the difference in the range of the ordinate axis between untreated and digested samples.) Depth-varying moduli are locally averaged within each zone (depth): superficial, middle and deep. Significance differences in moduli within individual plots are denoted by *p < 0.05 or ** p<0.0001 for depth, and †p<0.005 and ††p<0.001 for significance in applied strain.

Figure 7.

Incremental Young's moduli for mature sample groups over the applied strain range shown for both untreated (top, n=6) and digested (bottom, n=6) tested in 0.15M (left) and 2M (right) solutions. (Note the difference in the range of the ordinate axis between untreated and digested samples.) Depth-varying moduli are locally averaged within each zone (depth): superficial, middle and deep. Significance differences in moduli within individual plots are denoted by *p < 0.05 for depth, and †p<0.005 for significance in applied strain.

In the deep zone, the incremental Young's modulus was generally observed to decrease with increasing magnitude of compressive strain, in immature and mature tissue. This effect was most pronounced in native isotonic groups where, for example, the incremental modulus was as high as 6.8 MPa under 2% compression in immature tissue, dropping to 0.65 MPa at 20% compression. In the middle and superficial zones, the observed trend mostly suggested an initial reduction in incremental modulus with increasing compressive strain, followed by a small rise at higher compressive strains.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to examine the electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions of proteoglycans to the compressive modulus of articular cartilage. This investigation was motivated in part by the recognition that the osmotic pressure of chondroitin sulfate solutions in various concentrations of NaCl does not reduce to zero under hypertonic conditions (Chahine et al., 2005; Ehrlich et al., 1998), implying a significant contribution from non-electrostatic effects (Figure 8). Thus, in cartilage, the electrostatic contribution was assessed by measuring the modulus in isotonic and hypertonic saline; the total contribution of PGs was assessed by measuring the modulus in normal and digested tissue, with the expectation that the contribution from non-electrostatic effects may be deduced by comparison.

Figure 8.

Equilibrium osmotic pressure of chondroitin sulfate solutions measured from direct membrane osmometry, as a function of fixed charge density (25°C), in various NaCl concentrations. Solid lines indicate the corresponding virial expansion polynomial fits. Reproduced from Chahine et al. (2005) with permission.

The digestion protocol of Schmidt et al. (Schmidt et al., 1990) demonstrated nearly complete removal of PGs in immature tissue (~98%), and slightly lesser removal in mature tissue (~90%), consistent with the reduction of ~95% reported by these authors in 18 month old bovine patellofemoral groove cartilage. The difference in digestion between immature and mature samples may be due to tighter, more coalesced proteoglycan-collagen matrix interactions in mature tissue. The increase in collagen content per wet weight observed in mature tissue (Figure 1) is easily explained by examining the formula for calculating this content,

where w denotes weight. All else being equal, a reduction in PG content (such as wGAG = 0) produces an increase in the relative content of collagen. The fact that collagen (w/w) did not increase following PG digestion in immature samples can be explained by a concomitant increase in wwater, consistent with the observed increase in water (w/w) for that tissue.

Based on values of the apparent modulus representative of the full thickness of the articular layer (Figure 5) it becomes evident that PGs contribute at least 98% of the equilibrium compressive modulus of articular cartilage, as assessed from the immature tissue, which lost 98% of its PGs following digestion, and saw its modulus go down from 0.40±0.20 MPa to 8.7±2.1 kPa. The lesser reduction observed in the mature tissue (85% reduction, from 0.26±0.15 MPa to 40±12 kPa) is most likely due to the lesser digestion of PGs (90%), consistent with earlier studies of selective cartilage enzymatic digestions (Zhu et al., 1993).

In contrast, based on the apparent modulus, the electrostatic contribution of PGs under isotonic conditions represents approximately 62% of the equilibrium compressive modulus (0.40±0.20 MPa at 0.15 M NaCl versus 0.15±0.07 MPa at 2 M NaCl in immature cartilage). Therefore, by straightforward comparison, it may be concluded that the non-electrostatic contribution of PGs to the compressive equilibrium modulus is 98%-62%=36%, or approximately 1/3 of the total contribution.

The precise nature of this non-electrostatic contribution is not elucidated in this study, though it has been attributed to configurational entropy (Basser et al., 1998; Chahine et al., 2005; Ehrlich et al., 1998; Kovach, 1996). Otherwise, it is also possible that PGs contribute structurally to the compressive stiffness of the tissue even in a hypertonic salt bath, since they occupy a non-negligible portion (~20%) of the tissue's dry weight. In this context, a ‘structural’ contribution implies one that is not mediated via the osmotic pressure of the interstitial fluid (neither Donnan nor entropic). Further insight into the various contributions to the stiffness of PGs may be found in the study of Dean et al. (Dean et al., 2006), who measured the compressive nanomechanics of this molecule with atomic force microscopy.

The modulus of cartilage was observed to decrease with increasing compressive strain, especially in the deep zone of undigested tissue (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This apparent softening phenomenon has been reported previously (Schinagl et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2002) and examined closely in the study of Chahine et al. (Chahine et al., 2004). The basic explanation for this observation is that the osmotic pressure of the interstitial fluid places the collagen matrix under tension, causing it to swell. If the compressive strain applied on the tissue is smaller than the swelling strain, the tissue matrix remains under tension, so that the slope of its stress-strain response (the incremental Young's modulus) yields the tissue's tensile modulus, not its compressive modulus.

Indeed, the average value of 6.8 MPa reported for the immature undigested tissue under a platen-to-platen compressive strain of 2% is representative of the tensile equilibrium Young's modulus of immature bovine cartilage in the range of small tensile strains (Park and Ateshian, 2006). As the applied compressive strain increases in magnitude, the swelling strain is progressively overcome, leading to a transition from tensile to compressive strains in the collagen matrix. In the superficial and middle zones, the modulus typically achieves a minimum value at some intermediate applied strain, before increasing again slightly at the higher applied strains; this minimum value may be reasonably assumed to occur at the transition from tension to compression in the collagen matrix (Chahine et al., 2004). In the deep zone, this transition point is less apparent, suggesting that some small residual tensile strain may persist. Based on this behavior, it may be argued that the smallest value of the incremental modulus achieved over the range of applied strains is least influenced by the tensile modulus of the collagen matrix. This minimum value (obtained from the data shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7) is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Smallest value of incremental Young's modulus achieved over the range of applied strains (mean value, in units of MPa), believed to be least influenced by tensile strain in the collagen matrix. The electrostatic (ES) contribution of proteoglycans to the incremental modulus of native tissue at 0.15 M is evaluated from native values at 0.15 M and 2 M. The total (PG) contribution of proteoglycans is evaluated from the native value at 0.15 M and digested value at 2 M.

| Native (Undigested) | Digested | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immature | Mature | Immature | Mature | |||||||||

| 0.15M | 2M | ES (%) | PG (%) | 0.15M | 2 M | ES (%) | PG (%) | 0.15M | 2 M | 0.15M | 2M | |

| SZ | 0.070 | 0.039 | 44.3% | 96.1% | 0.149 | 0.039 | 73.8% | 85.9% | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.061 | 0.021 |

| MZ | 0.150 | 0.054 | 64.0% | 96.2% | 0.211 | 0.088 | 58.3% | 87.7% | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.067 | 0.026 |

| DZ | 0.652 | 0.218 | 66.6% | 98.5% | 0.563 | 0.144 | 74.4% | 95.0% | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.052 | 0.028 |

This observation of apparent softening, and its associated mechanism, is valuable in many respects. It allows us to better appreciate whether some amount of swelling persists in the tissue following PG digestion, or during testing in hypertonic NaCl. Indeed, following digestion, a small amount of softening remains visible under isotonic testing, in both immature and mature tissue. These results are consistent with the observation, from quantitative biochemical analysis, that a small amount of PGs remains in the tissue following digestion, causing this residual swelling. The fact that this small amount of PG is not visible from histology (Figure 2) is further evidence that histology provides only a qualitative assessment of tissue composition.

As expected, this softening behavior is also less significant when testing is performed in 2 M NaCl, consistent with our understanding that the swelling pressure and strain are smaller under hypertonic conditions. Not surprisingly, the least amount of softening occurs in digested samples tested in 2 M NaCl. Thus, the smallest modulus reported under these conditions is the most representative value of the compressive modulus of the collagen matrix of articular cartilage in the range of small compressive strains. This value ranges from 3 to 10 kPa in the various zones of immature cartilage, and from 21 kPa to 28 kPa in mature cartilage (Table 2). Allowing for some residual swelling in the middle and deep zones, as well as in the mature tissue, it is reasonable to estimate that the compressive modulus of the PG-free collagen matrix of cartilage is on the order of ~3 kPa or less. When placed in the context of constitutive modeling of articular cartilage as a proteoglycan gel reinforced by a collagen fibril matrix, these results suggest that it is quite reasonable to idealize the collagen matrix as sustaining tension only (Ateshian, 2007; Ateshian et al., 2009; Korhonen et al., 2003; Soltz and Ateshian, 2000; Soulhat et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2007). Furthermore, these results suggest that modeling the contribution of proteoglycans to the compressive modulus of cartilage should not be based solely on electrostatic interactions (Donnan effects), but should include their total contribution (be they entropic or structural) (Ateshian et al., 2009).

This study confirms prior findings that the apparent compressive modulus of cartilage increases from the superficial to the deep zone (Chahine et al., 2004; Guilak et al., 1995; Schinagl et al., 1997; Schinagl et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2002), as noted from the values of the incremental modulus achieved at the lowest applied strain (2%). This inhomogeneity implies that the strain in the tissue is not equal to the prescribed platen-to-platen value. Thus, in immature undigested samples subjected to a nominal compressive strain of 20%, the actual compression was 41.7±5.9%, 32.0±8.0%, and 8.7±1.4% on average, in the superficial, middle and deep zones respectively. A similar distribution was observed in the immature digested samples. However, the current study also suggests that the disparity in modulus among the zones is less drastic when the tensile swelling strain, induced by the proteoglycans, is significantly overcome (Table 2).

The localized collapse of the collagen matrix in digested mature samples (Figure 4) is consistent with prior studies that investigated the structural response of collagen fibers following PG digestion (Broom and Poole, 1983), and is indicative of the buckling instability of collagen fibers in the absence of a buttressing PG ground matrix. In addition, the faster relaxation of digested samples under loading is consistent with previous studies showing an altered temporal response in digested samples (Bader and Kempson, 1994; Basalo et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 1990).

The curling behavior observed in mature cartilage when it has been excised from the bone is indicative of residual stresses in the tissue. These residual stresses are generally attributed to the presence of the proteoglycan molecules which give rise to a swelling pressure in the tissue's interstitial fluid (Fry and Robertson, 1967; Maroudas, 1979; Setton et al., 1998). However, though the reduction in PG content was not complete, the persistence of curling in digested mature samples (Figure 3) is evidence that there are residual stresses in the collagen matrix not attributable to the osmotic pressure of the interstitial fluid, as also hinted in the results of Narmoneva et al. (Narmoneva et al., 1999; Narmoneva et al., 2001). These residual stresses likely result from collagen growth over time, under varying swelling conditions, such that collagen fibrils do not all share the same stress-free reference configuration (Humphrey and Rajagopal, 2002).

In summary, this study presents direct experimental evidence for assessing the electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions of proteoglycans to the compressive equilibrium modulus of bovine articular cartilage. Though it is well recognized that proteoglycans contribute significantly to the compressive stiffness of cartilage, this study demonstrates that the combined electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions add up to 98% of the modulus, a result not previously appreciated. Of this contribution, about two-thirds arise from electrostatic effects. The compressive modulus of the proteoglycan-depleted cartilage matrix may be as low as 3 kPa; experimental evidence also demonstrates that the collagen matrix in digested cartilage does buckle under compressive strains, resulting in crimping patterns. Thus, it is reasonable to model the collagen as a fibrillar matrix that can only sustain tension. This increased insight into the structure-function relationships of cartilage can lead to improved constitutive models and a better understanding of the response of cartilage to physiological loading conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AR46532).

APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Specimen Preparation

Articular cartilage cylindrical plugs (□6 mm) were harvested from healthy 4-6 week immature (n=6) and 3-4 year old mature (n=6) bovine humeral heads. To create parallel surfaces and to remove all subchondral bone and blood vessels, samples were microtomed using a sledge microtome (Model 1400; Leitz, Rockleigh, NJ, USA) equipped with a freezing stage (Hacker Instruments, Fairfield, NJ, USA). Specimens were then sub-punched from □6 mm to □3 mm with rings from sub-punching saved for biochemical analysis. Sub-punching was performed to ensure sidewalls perpendicular to the articular surface. Sub-punched specimens were subsequently sectioned in half yielding two semi-cylindrical samples. One half was immediately stored in phosphate-buffered saline (P4417 phosphate buffered saline tablet, Sigma-Aldrich, www.sigmaaldrich.com) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets, Roche Applied Science, IN, USA) (PBS + PI) at −20 C° until the day of testing.

Using the technique described by Schmidt et al. (Schmidt et al., 1990) the other halves were sequentially digested of GAGs to remove all components of the proteoglycan complex while leaving the collagen matrix intact. This 72 hour serial digestion consisted of three successive 24 hour treatments under gentle agitation as follows: (1) 0.125 units of chondroitinase ABC per ml of buffer solution containing 0.05 M Tris-HCL, 0.06 M sodium acetate, pH 8.0, along with protease inhibitors 2mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), 5 mM benzamidine HCI, and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide at 37°C ; (2) 1 mg of trypsin/m1 of buffer solution containing 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.2 at 25°C; and (3) 5 units of Streptomyces hyaluronidase per ml of buffer solution containing 0.05 M sodium acetate, 0.15 M NaCI, pH 6, plus the protease inhibitors used in step 1 at 37°C. All mentioned chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Following digestion, samples were stored at 4°C in PBS + PI until tested.

Biochemical Analysis

Biochemical analysis for composition was performed for each sample group: immature untreated, immature digested, mature untreated, and mature digested. Samples were weighed wet (MM20, Denver Instruments, CO), lyophilized overnight, re-weighed dry to determine water content. They were then digested for 16 h at 60°C in papain (Sigma Chemicals; in 0.1M sodium acetate buffer containing 0.05M EDTA and 0.01M cysteine-HCl) and the PG content was measured using 1,9 dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB, Sigma, MO) dye-binding assay that has been modified for use with microtiter plate reader, with shark chondroitin sulfate (0–50 mg/ml) used as a standard (Farndale et al., 1982).

Collagen content was determined by measuring orthohydroxyproline (OHP) content via the dimethylaminobenzaldehyde and chloramines T assay (Stegemann and Stalder, 1967), with a collagen:OHP ratio of 8:1 used as a conversion factor (Hollander et al., 1994). The collagen and GAG content was normalized to the sample wet weight. For histological analysis, the samples were fixed, serially dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin (Fisher Scientific), sectioned to 8 mm, and mounted onto microscope slides. The samples were then dewaxed, rehydrated, and stained with Safranin O (Sigma, MO) dye to determine the distribution of GAGs through the depth of the samples.

Testing Protocol and Image Analysis

Samples were tested in both isotonic 0.15 M PBS + PI solution and a hypertonic 2M PBS + PI solution; 2M PBS + PI was supplemented with the appropriate amount of NaCl to bring the solution to 2M and it was verified that the pH remained at 7.4. Samples were allowed to equilibrate in each solution for 1 hour before testing. Images of the sample's cross sectional area and thickness were taken post incubation and prior to testing, with a camera (Sony SSC-C50, Japan, 640 × 480 pixel resolution) mounted on a stereoscope (Olympus model SZ40, Olympus America, Melville, NY).

Samples were then compressed to 8% in 2% increments, and then to 14% and 20% compression, based on the original measured thickness. Testing was performed using a custom-built unconfined compression microscopy device used in previous studies (Wang et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002) where the sample is compressed between two impermeable glass platens and imaged from below with an inverted microscope (Olympus IX70; Melville, NY, 10X objective) using transmitted light, and images captured by digital camera (MicroMax 5 MHz; Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ USA). Compression was micrometer actuated and load was measured using a precision miniature load cell (Sensotec Inc., Columbus OH; range 0-250 grams). Images were captured at the start of each compression and after the samples had reached equilibrium.

Undigested samples were allowed to equilibrate for 20 minutes following compression, and digested samples for 10 minutes. The shortened time needed for the digested tissue to equilibrate was due to the altered viscoelasticity of the tissue (Schmidt et al., 1990), as confirmed in preliminary studies. Mature samples, both digested and undigested, exhibited curling when separated from the underlying subchondral bone (Setton et al., 1998). Therefore, during compression of these samples, the reference configuration was chosen at the point when the sample surfaces were just becoming flush with the opposing platens.

Data Analysis

Strain analysis of the images was performed using digital image correlation (DIC) software (Vic 2D, West Columbia, SC) yielding the strain distributions through the depth. In a rectangular region of interest (ROI), spanning from the articular surface to the deep zone, data distributed in the direction transverse to the loading direction were averaged to create a one-dimensional array of axial deformation, and corresponding strain values, through the depth of the sample.

In DIC, multiple images are acquired of a ROI that may be undergoing deformation. These images may be labeled Ik (k = 0 – n), where I0 represents the reference configuration X. Let xk represent the current configuration for the deformation, where x0 = X. The displacement field from I0 to Ik is given by uk(X) = xk (X)–X and the deformation gradient at the current configuration is given by Fk(X)=I+∂uk/∂X, where I is the identity tensor, from which the Lagrangian strain may be evaluated in a material frame.

When the deformation is sufficiently large, the DIC analysis is unable to provide the displacement uk accurately. In that case, it is more convenient to evaluate the incremental displacement Δuk(xk-1)=xk(xk-1)–xk-1 from two consecutive images Ik-1 and Ik (k = 1 – n). The corresponding incremental deformation gradient is given by ΔFk(xk-1)= I + ∂Δuk/∂xk-1; the cumulative deformation gradient at X is given by Fk(X)= ΔFk(X))ΔFk-1(X)... ΔF1(X). To obtain ΔFk(X) from ΔFk(xk-1), an algorithm was developed to track X forward by performing suitable interpolations.

Polarized Light Microscopy

Polarized light microscopy was used to identify the superficial, middle and deep zones in the immature and mature bovine humeral head (Canal et al., 2008). A total of eight unfixed cartilage slices were imaged (two slices each from two immature and two mature joints), and 80 μm thick samples were observed through the same inverted microscope as noted previously, equipped with differential interference contrast optics (Olympus America, Melville, NY, USA). Samples were observed with the superficial zone oriented at 45° to cross polarizers. Intensity profiles of the acquired grayscale images were analyzed (ImageJ, Bethesda, MD) to reveal locations of light extinction or fiber reorientation at the middle zone boundary points, from superficial to middle and from middle to deep. The boundaries between these zones were identified from inflexion points in the grayscale profile; their fractional location through the thickness was averaged over immature and mature samples.

Within each zone, the depth-dependent incremental Young's moduli were averaged to yield a mean zonal value of this material property at each nominal applied strain.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS v.8 software package (SAS Institute Inc., Carey, NC). Analysis of variance (α = 0.05) with repeated measures and post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pair-wise least-squares testing of the means, was used to detect differences in compressive Young's moduli with bathing concentration and enzymatic treatment. Differences in mean zonal incremental Young's moduli with bathing concentration, enzymatic treatment, and zone were similarly analyzed. ANOVA (α = 0.05) with Bonferroni post-hoc testing of means was used to detect differences in biochemical composition before digestion and after digestion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ateshian GA. Anisotropy of fibrous tissues in relation to the distribution of tensed and buckled fibers. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:240–249. doi: 10.1115/1.2486179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Chahine NO, Basalo IM, Hung CT. The correspondence between equilibrium biphasic and triphasic material properties in mixture models of articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2004;37:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00252-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Rajan V, Chahine NO, Canal CE, Hung CT. Modeling the matrix of articular cartilage using a continuous fiber angular distribution predicts many observed phenomena. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:061003. doi: 10.1115/1.3118773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeloglu EU, Albro MB, Thimmappa VA, Ateshian GA, Costa KD. Heterogeneous transmural proteoglycan distribution provides a mechanism for regulating residual stresses in the aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01027.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader DL, Kempson GE. The short-term compressive properties of adult human articular cartilage. Biomed Mater Eng. 1994;4:245–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalo IM, Chen FH, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Frictional response of bovine articular cartilage under creep loading following proteoglycan digestion with chondroitinase ABC. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:131–134. doi: 10.1115/1.2133764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalo IM, Mauck RL, Kelly TA, Nicoll SB, Chen FH, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Cartilage interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression following enzymatic digestion. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:779–786. doi: 10.1115/1.1824123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basalo IM, Raj D, Krishnan R, Chen FH, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Effects of enzymatic degradation on the frictional response of articular cartilage in stress relaxation. J Biomech. 2005;38:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Schneiderman R, Bank RA, Wachtel E, Maroudas A. Mechanical properties of the collagen network in human articular cartilage as measured by osmotic stress technique. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;351:207–219. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonassar LJ, Jeffries KA, Paguio CG, Grodzinsky AJ. Cartilage degradation and associated changes in biochemical and electromechanical properties. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1995;266:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom ND, Poole CA. Articular cartilage collagen and proteoglycans. Their functional interdependency. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:1111–1119. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canal CE, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Two-dimensional strain fields on the cross-section of the bovine humeral head under contact loading. J Biomech. 2008;41:3145–3151. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney SL, Billingham ME, Muir H, Sandy JD. Demonstration of increased proteoglycan turnover in cartilage explants from dogs with experimental osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 1984;2:201–206. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahine NO, Chen FH, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Direct measurement of osmotic pressure of glycosaminoglycan solutions by membrane osmometry at room temperature. Biophys J. 2005;89:1543–1550. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.057315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahine NO, Wang CC, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Anisotropic strain-dependent material properties of bovine articular cartilage in the transitional range from tension to compression. J Biomech. 2004;37:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean D, Han L, Grodzinsky AJ, Ortiz C. Compressive nanomechanics of opposing aggrecan macromolecules. J Biomech. 2006;39:2555–2565. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich S, Wolff N, Schneiderman R, Maroudas A, Parker KH, Winlove CP. The osmotic pressure of chondroitin sulphate solutions: experimental measurements and theoretical analysis. Biorheology. 1998;35:383–397. doi: 10.1016/s0006-355x(99)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg SR, Grodzinsky AJ. Swelling of articular cartilage and other connective tissues: electromechanochemical forces. J Orthop Res. 1985;3:148–159. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore SM, Sokoloff L, Norris G, Carmeci P. Nature of “imperfect” elasticity of articular cartilage. J Appl Physiol. 1963;18:393–396. [Google Scholar]

- Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connect Tissue Res. 1982;9:247–248. doi: 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry H, Robertson WV. Interlocked stresses in cartilage. Nature. 1967;215:53–54. doi: 10.1038/215053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilak F, Ratcliffe A, Mow VC. Chondrocyte deformation and local tissue strain in articular cartilage: a confocal microscopy study. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:410–421. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ED, Jr., Parker HG, Radin EL, Krane SM. Effects of proteolytic enzymes on structural and mechanical properties of cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 1972;15:497–503. doi: 10.1002/art.1780150505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander AP, Heathfield TF, Webber C, Iwata Y, Bourne R, Rorabeck C, Poole AR. Increased damage to type II collagen in osteoarthritic articular cartilage detected by a new immunoassay. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1722–1732. doi: 10.1172/JCI117156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JD, Rajagopal KR. A constrained mixture model for growth and remodeling of soft tissues. Math Model Meth Appl Sci. 2002;12:407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen RK, Laasanen MS, Toyras J, Lappalainen R, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. Fibril reinforced poroelastic model predicts specifically mechanical behavior of normal, proteoglycan depleted and collagen degraded articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2003;36:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach IS. A molecular theory of cartilage viscoelasticity. Biophys Chem. 1996;59:61–73. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(95)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC. A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:245–258. doi: 10.1115/1.2894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotke PA, Granda JL. Alterations in the permeability of articular cartilage by proteolytic enzymes. Arthritis Rheum. 1972;15:302–308. doi: 10.1002/art.1780150312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra T, Arokoski JP, Oksala N, Vihko A, Hyttinen M, Jurvelin JS, Kiviranta I. Experimental validation of arthroscopic cartilage stiffness measurement using enzymatically degraded cartilage samples. Phys Med Biol. 1999a;44:525–535. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/2/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyyra T, Kiviranta I, Vaatainen U, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. In vivo characterization of indentation stiffness of articular cartilage in the normal human knee. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999b;48:482–487. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(1999)48:4<482::aid-jbm13>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroudas A. Biophysical chemistry of cartilaginous tissues with special reference to solute and fluid transport. Biorheology. 1975;12:233–248. doi: 10.3233/bir-1975-123-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroudas A. Physicochemical properties of articular cartilage. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. Pitman Medical; Kent: 1979. pp. 215–290. [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt CA, Muir H. Biochemical changes in the cartilage of the knee in experimental and natural osteoarthritis in the dog. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:94–101. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B1.131804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mow VC, Gu WY, Chen FH. Structure and Function of Articular Cartilage and Meniscus. In: Huiskes V. C. M. a. R., editor. Basic Orthopaedic Biomechanics and Mechano-Biology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2005. pp. 181–258. [Google Scholar]

- Muir H. Structure and function of proteoglycans of cartilage and cell-matrix interactions. Soc Gen Physiol Ser. 1977;32:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir H. The chemistry of the ground substance of joint cartilage. In: Sokoloff L, editor. The Joints and Synovial Fluid. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1980. pp. 27–94. [Google Scholar]

- Narmoneva DA, Wang JY, Setton LA. Nonuniform swelling-induced residual strains in articular cartilage. J Biomech. 1999;32:401–408. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narmoneva DA, Wang JY, Setton LA. A noncontacting method for material property determination for articular cartilage from osmotic loading. Biophys J. 2001;81:3066–3076. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75945-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen MT, Toyras J, Rieppo J, Hakumaki JM, Silvennoinen J, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. Quantitative MR microscopy of enzymatically degraded articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:676–681. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200005)43:5<676::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek JT. The Donnan equilibrium. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1956;6:57–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Ateshian GA. Dynamic response of immature bovine articular cartilage in tension and compression, and nonlinear viscoelastic modeling of the tensile response. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:623–630. doi: 10.1115/1.2206201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JR, Black J. Mechanical behavior of articular cartilage: quantitative changes with alteration of ionic environment. J Biomech. 1979;12:765–773. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(79)90162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieppo J, Toyras J, Nieminen MT, Kovanen V, Hyttinen MM, Korhonen RK, Jurvelin JS, Helminen HJ. Structure-function relationships in enzymatically modified articular cartilage. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;175:121–132. doi: 10.1159/000074628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinagl RM, Gurskis D, Chen AC, Sah RL. Depth-dependent confined compression modulus of full-thickness bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:499–506. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinagl RM, Ting MK, Price JH, Sah RL. Video microscopy to quantitate the inhomogeneous equilibrium strain within articular cartilage during confined compression. Ann Biomed Eng. 1996;24:500–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02648112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MB, Mow VC, Chun LE, Eyre DR. Effects of proteoglycan extraction on the tensile behavior of articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:353–363. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setton LA, Tohyama H, Mow VC. Swelling and curling behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:355–361. doi: 10.1115/1.2798002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L. Elasticity of Articular Cartilage: Effect of Ions and Viscous Solutions. Science. 1963;141:1055–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3585.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. A Conewise Linear Elasticity mixture model for the analysis of tension-compression nonlinearity in articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:576–586. doi: 10.1115/1.1324669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulhat J, Buschmann MD, Shirazi-Adl A. A fibril-network-reinforced biphasic model of cartilage in unconfined compression. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:340–347. doi: 10.1115/1.2798330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann H, Stalder K. Determination of hydroxyproline. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;18:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyras J, Rieppo J, Nieminen MT, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS. Characterization of enzymatically induced degradation of articular cartilage using high frequency ultrasound. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:2723–2733. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/11/303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Chahine NO, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Optical determination of anisotropic material properties of bovine articular cartilage in compression. J Biomech. 2003;36:339–353. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Deng JM, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. An automated approach for direct measurement of two-dimensional strain distributions within articular cartilage under unconfined compression. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:557–567. doi: 10.1115/1.1503795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson AK, Chen AC, Sah RL. Compressive properties and function-composition relationships of developing bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W, Huyghe JM, van Donkelaar CC. Depth-dependent compressive equilibrium properties of articular cartilage explained by its composition. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2007;6:43–53. doi: 10.1007/s10237-006-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Mow VC, Koob TJ, Eyre DR. Viscoelastic shear properties of articular cartilage and the effects of glycosidase treatments. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:771–781. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.