Abstract

Large bacterial protein toxins autotranslocate functional effector domains to the eukaryotic cell cytosol, resulting in alterations to cellular functions that ultimately benefit the infecting pathogen. Among these toxins, the clostridial glucosylating toxins (CGTs) produced by Gram-positive bacteria and the multifunctional-autoprocessing RTX (MARTX) toxins of Gram-negative bacteria have distinct mechanisms for effector translocation, but a shared mechanism of post-translocation autoprocessing that releases these functional domains from the large holotoxins. These toxins carry an embedded cysteine protease domain (CPD) that is activated for autoprocessing by binding inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6), a molecule found exclusively in eukaryotic cells. Thus, InsP6-induced autoprocessing represents a unique mechanism for toxin effector delivery specifically within the target cell. This review summarizes recent studies of the structural and molecular events for activation of autoprocessing for both CGT and MARTX toxins, demonstrating both similar and potentially distinct aspects of autoprocessing among the toxins that utilize this method of activation and effector delivery.

Introduction

Pathogenic bacteria frequently export protein toxins that target eukaryotic intracellular proteins to alter host cell function to the benefit of the infectious pathogen. Different exported toxins employ distinct strategies for translocation of their cytopathic effectors from the bacterium into the host cell. These strategies include direct injection, such as occurs using Type III, Type IV [1], and likely also Type VI secretion [2]. By contrast, some toxins are secreted or released from the bacteria and then bind to host cell surface receptors via a binding (B) component. The B component itself or a separate translocation component then transfers the catalytic subunit or domain across the plasma or endosomal membrane into the cytosol. In some toxins, the B component is a protein subunit assembled with the effector (A) subunit within the bacteria before export (such as cholera toxin [3]), while for other toxins, the B and A subunits are exported separately and then assembled at the surface of the target cell (such as anthrax toxin [4]). Still other toxins are expressed as a single polypeptide that is nicked to separate the A and B domains by endogenous bacterial proteases (such as botulinum toxin [5]) or by host cell proteases during translocation (such as diphtheria toxin [6]). All of these processes succeed in delivering the smaller active effector domains or subunits into the host cell, where they can then access their intracellular protein targets.

Yet, questions have remained as to how single polypeptide toxins that range in size from 250 to 600 kDa deliver their effector domains to the eukaryotic cytosol. A shared strategy for activation of autocatalytic processing upon binding of the eukaryotic signal molecule inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) has recently been characterized for these toxins. This process represents a novel strategy for toxin activation and subsequent delivery of effectors to target cells.

Overview of Clostridial Glucosylating Toxins

Clostridial glucosylating toxins (CGTs), also known as large clostridial cytotoxins, are structurally and functionally related toxins produced by different Clostridium sp. that range in size from 250 to 308 kDa and have sequence identity from 26% to 76% [7], [8]. Clostridium difficile Toxin A (TcdA) and Toxin B (TcdB) are the major virulence factors of clinically important antibiotic-associated diarrheal infections and pseudomembranous colitis [9]. Recent studies revealed that, while some C. difficile strains produce both toxins, only TcdB is essential for virulence [10]. Other significant members of the CGT family are Lethal Toxin from C. sordellii (TcsL) and the α-toxin from C. novyi (Tcnα). These clostridia are more rare causes of disease, but have been associated with particularly severe invasive infections, including gas gangrene and toxic shock following abortions or gynecological procedures [11]–[14].

The CGTs are organized in a multidomain structure [15], including a biologically active effector domain, a middle translocation domain, and a C-terminal receptor-binding domain [8] (Figure 1A). To enter eukaryotic target cells, the secreted CGTs bind to extracellular receptors and follow the “short trip model” of exotoxin uptake [16]. After receptor-mediated endocytosis, a vesicular H+-ATPase leads to acidification of the early endosomes, inducing a conformational change and an increase in hydrophobicity [17]. A small hydrophobic region of the protein is proposed to form a pore through which the N-terminus-localized glucosyltransferase (GT) domain is translocated into the cytosol [18]–[20]. Using UDP-glucose (UDP-N-acetylglucosamine for Tcnα) as a co-substrate, the GT monoglucosylates Rho family GTPases. The covalent modification occurs at a specific threonine residue found within the GTP binding pocket (Thr37 in Rho, Thr35 in Rac), thereby preventing activation of the small GTPases by exchange of GTP for GDP. Ultimately, the accumulation of inactive GTPases results in reorganization of the cytoskeleton and other morphological changes [21].

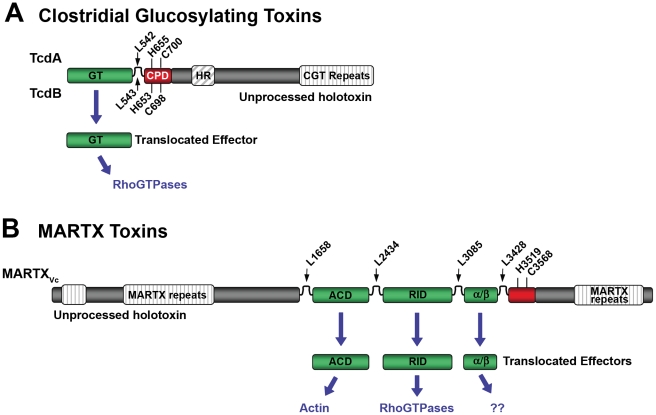

Figure 1. Schematic diagrams representing CPD-dependent autoprocessing sites within CGTs and MARTX toxins.

Diagrams are shown for (A) CGTs represented by TcdA and TcdB or (B) MARTX toxins represented by MARTXVc. In (A), the CGT holotoxins contain C-terminal repeats required for receptor interactions and a hydrophobic region (HR) postulated to function in translocation of the GT across the membrane of the endosome. Upon autoprocessing, the catalytically active glucosyltransferase effector (GT) is delivered to cells where it targets RhoGTPases. In (B), the MARTX holotoxin contains both N- and C-terminal repeats that likely function in translocation. Upon autoprocessing, MARTXVc delivers three effectors that have distinct cellular targets as indicated. For both diagrams, the CPD catalytic Cys and His are marked, as are processing site Leu residues (see Table 1) found in unstructured segments between effectors (indicated by arrows). For CGTs, sequence numbering above the diagram represents TcdA while numbering below the diagram represents TcdB. For MARTXVc, sequence numbering is based on the original annotation of the rtxA gene by Lin et al. [37] and may be different than that found in cited references.

Overview of Multifunctional-Autoprocessing RTX Toxins

Multifunctional-autoprocessing RTX (MARTX) toxins are larger toxins that range in size from 350 to 600 kDa [22]. The MARTX toxin of Vibrio cholerae (MARTXVc) has been linked to virulence, in which the toxin functions during early infection to promote colonization, possibly by inactivating cellular innate immunity [23]–[25]. The MARTX toxins from both human [26]–[29] and aquatic animal [30] infectious Vibrio vulnificus strains (MARTXVv) and the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum (MARTXVa) [31] have likewise been associated with virulence. In addition, putative MARTX toxins have been identified in at least 13 other sequenced Gram-negative bacteria, including Proteus, Aeromonas, Yersinia, and Photorhabdus spp. [22], [32]–[36], suggesting that additional pathogens require these toxins as virulence factors.

Similar to CGTs, the MARTX toxins are modular in structure, but are typified by the presence of extensive repeats at both the N- and C-termini [22], [37]. These repeats are postulated to form the translocation structure for transfer of centrally located effector domains to the cytosol [22] (Figure 1B). For MARTXVc, cytopathic effects occur in the presence of inhibitors of endocytosis [38]–[40], suggesting that endocytosis is not required for MARTX toxin entry, as it is for the CGTs.

Among the various MARTX toxins, a total of ten potential effectors have been identified, although each independent toxin has an assortment of only one to five [22]. The best-characterized MARTX effector is the actin crosslinking domain (ACD), which introduces a Glu270-Lys50 isopeptide linkage between actin monomers by a mechanism similar to that for glutamine synthetases [41], [42]. Another MARTX effector inactivates RhoGTPases by an unknown mechanism [43], although a recent bioinformatics study suggested this domain is a thiol protease [44]. The remaining eight potential effectors are domains of unknown function, even though two share sequence homology with Photorhabdus luminescens and Pasteurella multocida toxins and one is conserved with the alpha/beta hydrolase family of proteins [22].

Both CGT and MARTX Toxins Undergo Autoprocessing by a Conserved Cysteine Protease Domain

Early studies of the CGTs postulated that they would undergo enzymatic processing after exposure to low pH [17], [45]. Subsequent in vivo studies demonstrated that only the 60-kDa GT effector of TcdB is delivered to the cytosol, while a larger C-terminal fragment remains in the membrane fraction [20]. This processing of TcdB also occurred in vitro after residue Leu543, with a strict dependence upon addition of eukaryotic cell lysate [46] (Figure 1A). These studies of TcdB were initially interpreted as indicating processing by a host cell–encoded protease, similar to the mechanism for maturation of diphtheria toxin and other bacteria toxins [6]. However, protein-free extracts also stimulated TcdB processing, indicating autocataytic cleavage [47].

Similarly, early studies of MARTXVc postulated that the ACD would need to be released by proteolysis to access the entire actin pool [40]. In fact, it has been demonstrated that MARTXVc is autoprocessed at four positions located before and after its three effector domains, resulting in the release of these domains from the holotoxin [48], [49] (Figure 1B).

The autoprotease domain responsible for MARTXVc processing was recognized first as a 25-kDa domain within MARTXVc that affected cell viability when ectopically expressed in eukaryotic cells [50]. This cytotoxicity was disrupted by mutation of a single Cys or His residue, and analysis of protein expression patterns revealed that the mutant proteins were the predicted size, while the wild-type protein was cleaved of its N-terminus. Studies with recombinant protein confirmed autoprocessing after Leu3428 and, similar to TcdB, processing was strictly dependent upon addition of protein-free cell cytosol extracts [50]. Mutation of the critical Cys in the full-length toxin significantly reduced the ability of the toxin to induce actin crosslinking, confirming autoproteolysis due to this cysteine protease domain (CPD) enhanced toxin function [50].

After its discovery within MARTXVc, the CPD was found to be conserved within all MARTX toxins and also in all CGTs, with common alignment of the processing sites and the catalytic Cys and His residues [50], [51]. Furthermore, for TcdB, mutation of the analogous Cys and His residues reduced cytotoxicity of the full-length toxin, and disrupted processing of recombinant CPD protein as well [51], [52]. Thus, it was recognized that both the CGTs and MARTX toxins share a common mechanism for autocatalytic processing inducible by protein-free eukaryotic cell cytosol and that autoprocessing is essential for optimal cytotoxicity.

InsP6: The Inducer of Autoprocessing

To identify the molecule in cell cytosol required to induce CPD for autoprocessing, cell extracts that stimulated processing of TcdB were fractionated and analysis of active fractions by mass spectrometry supplied spectra with similarities to inositol phosphates [47]. Incubation of TcdB with several inositol phosphates indicated that InsP6 induced the most efficient autoprocessing activity [47]. Similar studies indicated that InsP6 is likewise the most effective stimulator of autoprocessing of the MARTXVc CPD [53].

As a signal molecule for the eukaryotic intracellular environment, InsP6 (also known as phytic acid) is an excellent selection for bacterial toxins, since the molecule is ubiquitous in eukaryotes but absent in bacteria. Furthermore, InsP6 is the most abundant of the inositol phosphates, is maintained within cells at relatively constant levels of 10–60 µM, and is generally freely soluble in the cytoplasm [54]. Within mammalian cells, InsP6 may function as a high concentration storage molecule for phosphate as it does in plant seeds or as a highly charged buffer for cation- or protein-dependent processes. More recent studies have linked InsP6 to numerous cellular processes, including vesicle recycling, mRNA transport out of the nucleus, and as a co-factor for a DNA-dependent protein kinase [54]. Regardless of its normal function, InsP6 is a molecule constantly present in high concentrations in the eukaryotic cytosol, assuring that induction of CGT and MARTX CPDs occurs only after completion of translocation of effector domains to the cytosol, regardless of whether translocation requires endocytosis or transfer directly across the plasma membrane.

InsP6 Binding to the CPDs

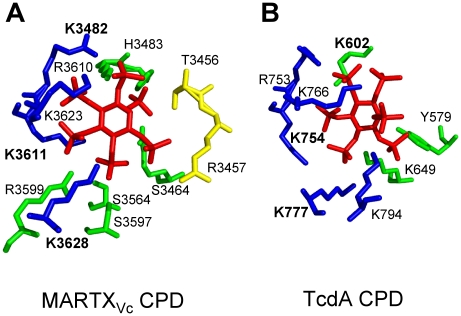

While both CGT and MARTX CPDs are induced for autoprocessing by InsP6, there are differences in these proteins revealed by crystallography and InsP6 binding studies that suggest slightly different mechanisms of activation. Mutational studies [53], [55]–[57] and analysis of four independent crystal structures [48], [49], [56], [57] revealed that binding of InsP6 to the CPD involves contact of the six negatively charged phosphate groups within a positively charged pocket of the CPD (Figure 2). The most significant binding contacts of MARTXVc with InsP6 involve Lys3482, Lys3611, and Lys3623. Other Lys, Arg, and positively charged residues that form the binding pocket are not essential for binding, but do contribute to the high affinity of the MARTXVc CPD for InsP6 [53], [56]. In TcdB, Lys600 (analogous to Lys3481 of MARTXVc) is likewise essential for binding of InsP6 [55], while other conserved Lys and Arg residues also contact InsP6 [55], [57]. Interestingly, overlay of the structures of the CPD from MARTXVc and TcdA CPDs revealed that the orientation of InsP6 in the binding pocket is not conserved [57] (Figure 2), which is a surprise since amino acid sequence alignments show strong conservation of the Lys and Arg residues that form the binding pocket [55], [57]. However, this difference in the structure of the binding pocket may in part account for variances revealed in studies of InsP6 binding and CPD activation for the different CPDs.

Figure 2. Side chain residues from CPD that contact InsP6 in the structural models derived from crystal structures of MARTXVc and TcdA CPD.

All key residues that contact InsP6 in the CPD of (A) MARTXVc and (B) TcdA are shown labeled with a single letter code, with the three Lys residues determined to be most critical for InsP6 binding shown in bold text. Interestingly, despite strong conservation of the critical Lys residues in the primary amino acid sequence, contacts with InsP6 and the orientation of InsP6 differ in the two structures. Diagram is colored to represent residues originating from the N-terminal strand (yellow), the core structure (green), and β-strands G1-G5 (blue), a structure also known as β8-β12 or the β-flap. Structural models were based on PDB (A) 3FZY [48] and (B) 3HO6 [57], and figures were prepared with MacPyMol software (DeLano Scientific).

Intramolecular processing of purified MARTXVc CPD was found to be optimal in the range of 0.001–1 µM InsP6 [53], [56], and binding of InsP6 occurred with affinities ranging from 0.2 to 1.3 µM InsP6 [48], [53], [56]. The ability of MARTXVc CPD to complete autoprocessing in vitro at concentrations below the dissociation constant reflects the recycling of InsP6 released from processed CPD back to predominantly unprocessed protein [53], since processed MARTXVc CPD has a 500-fold reduced affinity for InsP6 [48].

By contrast, activation of purified TcdB CPD autoprocessing requires 2 µM InsP6 [51], a concentration near the determined Kd of 2.3 µM [55]. Furthermore, recombinant TcdB CPD that mimics protein processed after Leu543 binds InsP6 with a similar affinity as full-length TcdB and unprocessed recombinant CPD [55], suggesting that TcdB CPD, unlike MARTXVc CPD, does not have an altered affinity for InsP6 after processing.

Although the dissociation constant has not as yet been determined for TcdA, processing studies indicate that its ability to bind InsP6 may be less efficient than TcdB. Whereas full-length TcdB is cleaved to completion at InsP6 concentrations of 2–10 µM [47], [51], full-length TcdA does not autoprocess at 10 µM InsP6 and concentrations up to 10 mM have been used for experimentation [47], [51]. However, recombinant TcdA CPD does autoprocess at concentrations as low as 5 µM [57], suggesting that the affinity of TcdA CPD for InsP6 could be near to that of TcdB, but not accurately reflected in holotoxin cleavage assays.

Despite the apparent differences in the structure of the InsP6 binding pocket and binding kinetics, the high affinity of the unprocessed CPDs for InsP6 indicates that autoprocessing of MARTXVc, TcdB, and TcdA would all proceed efficiently at InsP6 concentrations of 10–60 µM that are found in the eukaryotic cell cytosol [54]. Thus, all of the studied CGT and MARTX toxins would be autoprocessed and effectively deliver their effector domains within the in vivo environment.

Structural Arrangement of the CPD Catalytic Site

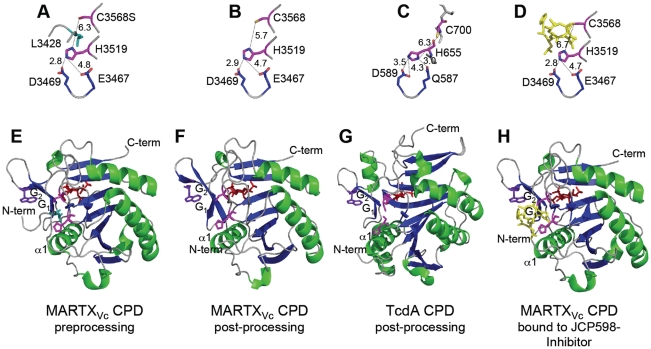

The CPD catalytic dyad is composed of one His and one Cys residue separated by ∼6 Å in both MARTXVc and TcdA structures [48], [56], [57] (Figure 3A–3D). The distance between the catalytic residues indicates that the Cys is not activated by protonation from His, but rather suggests that the Cys is substrate-activated by close alignment of the scissile bond, while the His functions solely to protonate the leaving group [48], [57].

Figure 3. Crystal structures of MARTXVc and TcdA CPDs.

Crystal structures of the (A–D) CPD catalytic sites with distances between residues designated in angstroms and (E–G) the CPD proteins are shown at various stages of processing. (A, E) Pre-processing and (B, F) post-processing structures of MARTXVc CPD bound to InsP6 (PDB 3FZY [48] and PDB 3EEB [56], respectively). (C, G) Post-processing structures of TcdA CPD bound to InsP6 (PDB 3HO6 [57]). (D, H) Post-processing structure of MARTXVc bound to z-Leu-Leu-azaLeu-epoxide inhibitor JCP598 as a surrogate substrate representing the structure of CPD after reactivation (PDB 3GCD [49]). Structures are identically oriented at a conserved Trp (purple) in the G1/G2 β-hairpin that is critical to InsP6 induction of autoprocessing [56]. The catalytic Cys and His residues are shown in pink with InsP6 present at the backside of each structure in red. The P1 Leu (turquoise) is found only in the unprocessed structure (A) with the scissile bond oriented between the catalytic residues. Figures were prepared with MacPyMol software (DeLano Scientific).

In addition, Asp and Glu residues play an essential function in proteolysis. Mutation of TcdB Asp567 or TcdA Asp589 disrupted autoprocessing [51], [57] and eliminated cytopathic effects when added to HeLa cells [55]. By contrast, mutation of the analogous Asp3469 in the MARTXVc CPD did not affect autoprocessing [53]. Analysis of the structural models indicates that this conserved Asp residue functions in both proteins to properly orient the catalytic His residue [48], [57] (Figure 3A–3D). However, in the MARTXVc CPD structure, this function is shared with residue Glu3467, such that only a double Asp/Glu mutant is defective for function [53].

The closest known cysteine proteases that share this structural arrangement of the catalytic site are caspase-1 and gingipain R [58], [59]. Similar to these other proteases [60], [61], the CPDs are resistant to cysteine protease inhibitor E64 [50], but sensitive to N-ethylmaleimide, iodoacetamide, or chloromethyl ketones [48], [50], [51]. Thus, the CGT and MARTX toxin CPDs are grouped together with caspase-1 and gingipain R in the CD clan of cysteine proteases, but form a new family, the C80 family (http://merops.sanger.ac.uk, [62]). The CPD proteases have also been incorporated into a larger CPDadh family of putative bacterial and eukaryotic peptidase that are proposed to share a similar fold in the catalytic site [63].

Structure-Based Modeling of InsP6-Induced Activation of the CPDs

As the binding site for InsP6 occurs on the opposite side of the protein from the catalytic site (Figure 3E–3H), it was recognized that there must be a mechanism to transduce the binding signal across the entire protein structure [56]. Translocation of effector domains of both CGTs and MARTX toxins is predicted to involve transit through a pore for entry into the cytosol, and thus the CPD is likely partially unfolded when it is first presented to the InsP6-rich environment of the cytosol [15], [22]. Consistent with this model, apo-CPD in the absence of InsP6 for both MARTXVc and TcdA is highly sensitive to proteolysis [48], [57]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies of the TcdA CPD indicated that the apo-protein is folded, but undergoes a significant conformational reorganization upon InsP6 binding [57]. This finding is consistent with an observed high negative enthalpy and entropy and a 14°C thermal stability shift upon binding of InsP6 to MARTXVc CPD, suggesting that this protein undergoes a major structural rearrangement that also stabilizes the protein structure [48].

Upon binding InsP6, the structure of the MARTXVc CPD adopts the stable conformation amenable to X-ray crystallography (Figure 3E–3G). The CPD is composed of a seven-stranded β-sheet with two α-helices flanking the sheet and one capping the sheet [56]. An additional five β-strands at the C-terminus form a subdomain, known as the β-flap, that is loosely attached to the core of the protease [56]. By contrast, the TcdA CPD is larger and consists of a nine-stranded β-sheet flanked by five α-helices (Figure 3G) [57]. In both proteins, the N-terminus is an unstructured strand wrapped around the outside of the protein and attached to the core structure by embedding of large hydrophobic residues [48], [57]. At the extreme N-terminus of the CPD, the P1 Leu residue found immediately before the scissile bond is buried in a hydrophobic pocket (Figure 3E) [48]. Mutagenesis studies and structural analysis [48], [49] have demonstrated that Leu is the only residue that can be accommodated at this position. On either side of the Leu, any residue can occur but there is a preference for small residues, creating a consensus sequence of small-Leu-small ([48], [49] and Table 1). The G1 β-strand (also known as β8) forms part of the hydrophobic pocket [56], and conserved Leu and Val residues on this strand make direct contact with the P1 Leu before the scissile bond [48]. This G1 strand is antiparallel to the G2 β-strand (also known as β9), a strand that contributes positively charged amino acids that make contact with InsP6 [56]. The current model for activation of the MARTXVc CPD proposes that binding of InsP6 alters the structure of this antiparallel β-hairpin, resulting in stabilization of the N-terminus within the hydrophobic pocket [48] and possibly reorientation of the catalytic Cys [56]. The net effect is to orient the scissile bond between the catalytic Cys and His residues, resulting in substrate-activated autoprocessing [48] (Figure 4). A similar mechanism has been proposed for the activation of TcdA CPD [57].

Table 1. InsP6-induced autoprocessing CGTs and MARTX toxins.

| Toxin Group | Bacterial Toxin (Abbreviation) | Number of Effectorsa | Cellular Targetsa | Processing Sitesb | Reference |

| CGT | C. difficile Toxin A (TcdA) | 1 | RhoGTPases | GGSL542↓SED (p) | [47], [51] |

| C. difficile 8864 Toxin B (TcdB8864) | 1 | RhoGTPases | EGAL543↓GED (m) | [46] | |

| C. difficile 10463 Toxin B (TcdB) | 1 | RhoGTPases | EGSL543↓GED (m) | [46] | |

| C. novyi Alpha toxin (Tcnα) | 1 | RhoGTPases | GRTL548↓NYE (p) | [46], [47] | |

| C. sordellii Lethal toxin (TcsL) | 1 | RhoGTPases | EGAL543↓GED (p) | [46] | |

| MARTX | V. cholerae MARTXVc | 3 | Actin, RhoGTPases, ?? | LESL1658↓SAV (m) | [48] |

| LHAL2434↓GET (m) | [48], [49] | ||||

| LDAL3085↓SGN (m) | [48], [49] | ||||

| KEAL3428↓ADG (m) | [50] | ||||

| QQGL3402↓DTT (a) | [49] | ||||

| NDHL3419↓AVV (a) | [48] | ||||

| V. vulnificus MARTXVv | 5 | RhoGTPases, ?? | KGSL4089↓SGA (m) | [49] | |

| P. luminescens MARTXplu1341 | 1 | ?? | LQAL2538↓SGK (p) | [49] | |

| P. luminescens MARTXplu1344 | 2 | ?? | SGAL2962↓MSQ (p) | [49] | |

| P. luminescens MARTXplu3217 | 1 | ?? | LDWL2408↓SGK (m) | [49] | |

| VEAL2405↓DWL (a) | [49] | ||||

| P. luminescens MARTXplu3324 | 1 | ?? | LEGL2418↓SGT (p) | [49] |

Processing site is indicated by inverted arrow. m, processing site as mapped experimentally by N-terminal sequencing or mass spectrometry; p, processing site predicted by homology to mapped processing site from closely related toxin; a, alternative processing site identified by mass spectrometry. Numbering of MARTXVc processing sites is based on amino acid sequence as originally annotated in [37] and may be different than that found in cited references. For other MARTX toxins, not all processing sites are known and only those previously reported in the literature are listed.

Figure 4. Proposed model for cooperative activation and reactivation of MARTXVc CPD by InsP6.

I. Apo-CPD without InsP6 is an unstable protein susceptible to thermal denaturation at physiological temperature. The core structure (green) is folded but the β-flap (blue) is susceptible to proteolysis, indicating it may be only partially structured. II. Upon binding InsP6, the structure rearranges such that the N-terminus (yellow) becomes locked within the active site between the catalytic Cys (C) and His (H) in a rigid alignment amenable to substrate-activated autoprocessing. III. After autoprocessing, the MARTXVc CPD enters a transitional state that has distinct biochemical properties, including a 500-fold reduced affinity for InsP6. IV. After first binding a new substrate (grey) and then a new molecule of InsP6, the enzyme–substrate complex structure of the MARTXVc CPD is restored for additional processing events. Figure is based on multisite processing model for MARTXVc proposed by Prochazkova et al. [48]. Current evidence from NMR studies supports the idea that stage I and II also occur for TcdA [57]. However, binding studies with TcdB suggest CGTs likely do not undergo stage III deactivation or stage IV reactivation [55].

Multisite Processing of MARTXVc

The CGT toxins require only a single processing event to release their GT effector domain (Figure 1A), and this may account for why activation apparently requires a structural change between two apparently stable conformations at approximately 5 µM InsP6 [57]. By contrast, MARTX toxins must undergo processing at multiple sites to release each of the effectors independently [48], [49] (Figure 1B). A simplistic model of multisite processing would predict that activation of the CPD by binding of InsP6 results in transition to a constitutive “on” conformation after which it processes all accessible sites immediately [56]. Yet, biochemical studies described above indicated that after processing of its own N-terminus, MARTXVc CPD converts to an inactive conformation with a 500-fold reduced affinity for InsP6 (Kd = 100 µM) [48] (Figure 4). Since this concentration is above the upper limit of the in vivo concentration of InsP6 [54], only a small fraction of processed CPD would bind InsP6 in vivo, limiting the likelihood of multisite processing. However, it was found that reactivation of MARTXVc CPD for high affinity binding of InsP6 occurs after insertion of a new substrate into the hydrophobic pocket, indicating cooperativity of substrate and InsP6 binding [48]. Both binding studies [48] and crystallography [49] (Figure 3G) have shown that chloromethyl ketone and epoxide inhibitors bound to Leu can substitute for a new substrate to restore the protein to an active enzyme-substrate complex. Upon reactivation, the protein is able to process any other available processing sites [48], [49], although there is a preference for processing within the same molecule of MARTXVc, indicating there may be a physical association of the CPD with the effector domains [48].

Potential of CPD as a Target for Therapeutic Intervention

The discovery of InsP6-induced autoproteolysis as a critical stage for activation and effector delivery for large bacterial toxins raises the potential for anti-toxin small molecules to be developed as therapeutics. TcdB is the most significant virulence factor of C. difficile [9], [10], and it is conceivable that specific TcdB anti-toxin drugs could be combined with antibiotic and anti-toxin antibody therapies for treatment of recurrent antibiotic-associated diarrhea [64]. In addition, the contribution of MARTXVv to V. vulnificus septicemic infection is significant [26]–[29], suggesting that anti-MARTXVv CPD therapeutics may be of interest, particularly since there are currently no anti-toxin treatments for these rapidly progressing fatal infections. By contrast, clinical intervention against any domain of MARTXVc during cholera disease is impractical since animal studies suggest that MARTXVc functions only during the earliest stage of infection, prior to the onset of symptoms [24], [25]. Indeed, classical V. cholerae strains responsible for severe cholera during the fifth and sixth pandemics have a natural deletion in the rtxA gene that encodes MARTXVc, demonstrating that it is dispensable for late stage infection [37].

For research purposes, potent small molecule inhibitors of the MARTXVc CPD activity have been identified. These include peptidyl (acyloxy)methyl ketone epoxide [49] and chloromethyl ketone [48] inhibitors in which the amino acid leucine is linked to the functional group independently or as part of a tripeptide. Both classes of inhibitor are cysteine reactive and become covalently linked to the catalytic cysteine (Figure 3D). However, analysis of the pre-processed form of MARTXVc CPD revealed the N-terminus is bound within the active site prior to InsP6 binding, which occludes access of the catalytic Cys to protease inhibitors. Thus, inactivation of the CPD with Cys reactive inhibitors requires long incubation times of up to 30 minutes [48]. Yet, upon initial intramolecular processing immediately upstream of the CPD, the catalytic Cys is exposed, facilitating rapid inhibition of subsequent processing events that release effectors [48], [49]. Consistent with these in vitro findings, exogenous addition of the membrane permeant z-Leu-Leu-azaLeu-epoxide inhibitor JCP598 to culture cells reduced actin crosslinking in vivo [49], suggesting inhibitors could be useful at a critical point after CPD translocation.

Similar inhibition studies using the more clinically relevant TcdB remain to be performed. Since the CGTs are only processed one time (Figure 1A), there is a concern that cysteine reactive inhibitors would be ineffective if the N-terminus bound in the active site blocks access to the catalytic Cys. A structure of the enzyme-substrate complex of TcdA or TcdB CPD is not yet available and inhibition by N-ethylmaleimide has been performed only with 30 minutes of incubation [51]. Thus, it is unknown if the accessibility of the Cys will be blocked similar to MARTXVc CPD. As described above, binding of InsP6 to the recombinant TcdB CPD protein with the P1 leucine removed has been measured and shown to be similar to that with the Leu attached [55]. These results thereby suggest the association of the N-terminus with the TcdB catalytic site and relevant exposure of the catalytic site to inhibitors may differ from MARTXVc CPD. Hence, the potential for inhibition of InsP6-induced autoprocessing by CPDs as a therapeutic intervention against TcdB merits further exploration. If access to the cysteine is indeed found to be blocked, the CPD could still be a suitable target for therapeutics, but with molecules that mimic InsP6 itself to promote processing outside of cells, potentially disrupting the entire translocation/activation process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Queen and Brett Geissler for reading the manuscript. We also thank the reviewers of the initial draft for their insightful contributions.

Footnotes

KJFS has a pending patent application that describes use of the CPD for biotechnological applications.

ME is supported by a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation). KJFS is supported by an Investigator in Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and by grants RO1 AI051490 and R21 AI072461 from the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wooldridge K, editor. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academic Press; 2009. Bacterial Secreted Proteins: Secretory Mechanisms and Role in Pathogenesis.511 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma AT, McAuley S, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ. Translocation of a Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion effector requires bacterial endocytosis by host cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez J, Holmgren J. Cholera toxin structure, gene regulation and pathophysiological and immunological aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1347–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7496-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young JA, Collier RJ. Anthrax toxin: receptor binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin MR, Barbieri JT. Association of botulinum neurotoxins with synaptic vesicle protein complexes. Toxicon. 2009;54:570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon VM, Leppla SH. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins: role of bacterial and host cell proteases. Infect Immun. 1994;62:333–340. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.333-340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch C, Aktories K. Microbial toxins and the glycosylation of Rho family GTPases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:528–535. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Eichel-Streiber C, Boquet P, Sauerborn M, Thelestam M. Large clostridial cytotoxins–a family of glycosyltransferases modifying small GTP-binding proteins. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:334–339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyras D, O'Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009;458:1176–1179. doi: 10.1038/nature07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen AL, Bhatnagar J, Reagan S, Zane SB, D'Angeli MA, et al. Toxic shock associated with Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens after medical and spontaneous abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1027–1033. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287291.19230.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer M, Bhatnagar J, Guarner J, Reagan S, Hacker JK, et al. Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2352–2360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miech RP. Pathophysiology of mifepristone-induced septic shock due to Clostridium sordellii. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1483–1488. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samlaska CP, Maggio KL. Subcutaneous emphysema. Adv Dermatol. 1996;11:117–151; discussion 152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belyi Y, Aktories K. Bacterial toxin and effector glycosyltransferases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandvig K, Spilsberg B, Lauvrak SU, Torgersen ML, Iversen TG, et al. Pathways followed by protein toxins into cells. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293:483–490. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qa'Dan M, Spyres LM, Ballard JD. pH-induced conformational changes in Clostridium difficile Toxin B. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2470–2474. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2470-2474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barth H, Pfeifer G, Hofmann F, Maier E, Benz R, et al. Low pH-induced formation of ion channels by Clostridium difficile Toxin B in target cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10670–10676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giesemann T, Jank T, Gerhard R, Maier E, Just I, et al. Cholesterol-dependent pore formation of Clostridium difficile Toxin A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10808–10815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeifer G, Schirmer J, Leemhuis J, Busch C, Meyer DK, et al. Cellular uptake of Clostridium difficile Toxin B. Translocation of the N-terminal catalytic domain into the cytosol of eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44535–44541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Just I, Selzer J, Wilm M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Mann M, et al. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile Toxin B. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satchell KJ. MARTX: Multifunctional-Autoprocessing RTX Toxins. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5079–5084. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00525-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olivier V, Haines GK, 3rd, Tan Y, Satchell KJ. Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5035–5042. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivier V, Queen J, Satchell KJ. Successful small intestine colonization of adult mice by Vibrio cholerae requires ketamine anesthesia and accessory toxins. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivier V, Salzman NH, Satchell KJ. Prolonged colonization of mice by Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 depends on accessory toxins. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5043–5051. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00508-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung KJ, Cho EJ, Kim MK, Kim YR, Kim SH, et al. RtxA1-induced expression of the small GTPase Rac2 plays a key role in the pathogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:97–105. doi: 10.1086/648612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YR, Lee SE, Kook H, Yeom JA, Na HS, et al. Vibrio vulnificus RTX toxin kills host cells only after contact of the bacteria with host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:848–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JH, Kim MW, Kim BS, Kim SM, Lee BC, et al. Identification and characterization of the Vibrio vulnificus rtxA essential for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in mice. J Microbiol. 2007;45:146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu M, Alice AF, Naka H, Crosa JH. The HlyU protein is a positive regulator of rtxA1, a gene responsible for cytotoxicity and virulence in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3282–3289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CT, Amaro C, Wu KM, Valiente E, Chang YF, et al. A common virulence plasmid in biotype 2 Vibrio vulnificus and its dissemination aided by a conjugal plasmid. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1638–1648. doi: 10.1128/JB.01484-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Rock JL, Nelson DR. Identification and characterization of a repeat-in-toxin gene cluster in Vibrio anguillarum. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2620–2632. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01308-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seshadri R, Joseph SW, Chopra AK, Sha J, Shaw J, et al. Genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966T: jack of all trades. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8272–8282. doi: 10.1128/JB.00621-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, et al. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4027–4037. doi: 10.1128/JB.01981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson NR, Howard S, Wren BW, Holden MT, Crossman L, et al. The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson P, Waterfield NR, Crossman L, Corton C, Sanchez-Contreras M, et al. Comparative genomics of the emerging human pathogen Photorhabdus asymbiotica with the insect pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duchaud E, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Givaudan A, et al. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin W, Fullner KJ, Clayton R, Sexton JA, Rogers MB, et al. Identification of a Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin gene cluster that is tightly linked to the cholera toxin prophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1071–1076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordero CL, Kudryashov DS, Reisler E, Satchell KJ. The actin cross-linking domain of the Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin directly catalyzes the covalent cross-linking of actin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32366–32374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605275200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fullner KJ, Mekalanos JJ. In vivo covalent crosslinking of actin by the RTX toxin of Vibrio cholerae. EMBO J. 2000;19:5315–5323. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheahan KL, Cordero CL, Satchell KJ. Identification of a domain within the multifunctional Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin that covalently cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9798–9803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401104101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geissler B, Bonebrake A, Sheahan KL, Walker ME, Satchell KJ. Genetic determination of essential residues of the Vibrio cholerae actin cross-linking domain reveals functional similarity with glutamine synthetases. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:858–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kudryashov DS, Durer ZA, Ytterberg AJ, Sawaya MR, Pashkov I, et al. Connecting actin monomers by iso-peptide bond is a toxicity mechanism of the Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18537–18542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheahan KL, Satchell KJ. Inactivation of small Rho GTPases by the multifunctional RTX toxin from Vibrio cholerae. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1324–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pei J, Grishin NV. The Rho GTPase inactivation domain in Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin has a circularly permuted papain-like thiol protease fold. Proteins. 2009;77:413–419. doi: 10.1002/prot.22447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henriques B, Florin I, Thelestam M. Cellular internalisation of Clostridium difficile Toxin A. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:455–463. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rupnik M, Pabst S, Rupnik M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Urlaub H, et al. Characterization of the cleavage site and function of resulting cleavage fragments after limited proteolysis of Clostridium difficile Toxin B (TcdB) by host cells. Microbiology. 2005;151:199–208. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reineke J, Tenzer S, Rupnik M, Koschinski A, Hasselmayer O, et al. Autocatalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile Toxin B. Nature. 2007;446:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature05622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prochazkova K, Shuvalova LA, Minasov G, Voburka Z, Anderson WF, et al. Structural and molecular mechanism for autoprocessing of MARTX Toxin of Vibrio cholerae at multiple sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26557–26568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen A, Lupardus PJ, Albrow VE, Guzzetta A, Powers JC, et al. Mechanistic and structural insights into the proteolytic activation of Vibrio cholerae MARTX toxin. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheahan KL, Cordero CL, Satchell KJ. Autoprocessing of the Vibrio cholerae RTX toxin by the cysteine protease domain. EMBO J. 2007;26:2552–2561. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Egerer M, Giesemann T, Jank T, Satchell KJ, Aktories K. Auto-catalytic cleavage of Clostridium difficile Toxins A and B depends on cysteine protease activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25314–25321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barroso LA, Moncrief JS, Lyerly DM, Wilkins TD. Mutagenesis of the Clostridium difficile Toxin B gene and effect on cytotoxic activity. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:297–303. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prochazkova K, Satchell KJ. Structure-function analysis of inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing of the Vibrio cholerae multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23656–23664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803334200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Irvine RF, Schell MJ. Back in the water: the return of the inositol phosphates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:327–338. doi: 10.1038/35073015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Egerer M, Giesemann T, Herrmann C, Aktories K. Autocatalytic processing of Clostridium difficile Toxin B. Binding of inositol hexakisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3389–3395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lupardus PJ, Shen A, Bogyo M, Garcia KC. Small molecule-induced allosteric activation of the Vibrio cholerae RTX cysteine protease domain. Science. 2008;322:265–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1162403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pruitt RN, Chagot B, Cover M, Chazin WJ, Spiller B, et al. Structure-Function analysis of inositol hexakisphosphate-induced autoprocessing in Clostridium difficile Toxin A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21934–21940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eichinger A, Beisel HG, Jacob U, Huber R, Medrano FJ, et al. Crystal structure of gingipain R: an Arg-specific bacterial cysteine proteinase with a caspase-like fold. EMBO J. 1999;18:5453–5462. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson KP, Black JA, Thomson JA, Kim EE, Griffith JP, et al. Structure and mechanism of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Nature. 1994;370:270–275. doi: 10.1038/370270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buttle DJ, Saklatvala J, Tamai M, Barrett AJ. Inhibition of interleukin 1-stimulated cartilage proteoglycan degradation by a lipophilic inactivator of cysteine endopeptidases. Biochem J. 1992;281 (Pt 1):175–177. doi: 10.1042/bj2810175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kembhavi AA, Buttle DJ, Knight CG, Barrett AJ. The two cysteine endopeptidases of legume seeds: purification and characterization by use of specific fluorometric assays. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303:208–213. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Kok CY, Kong J, Barrett AJ. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D320–D325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pei J, Lupardus PJ, Garcia KC, Grishin NV. CPDadh: a new peptidase family homologous to the cysteine protease domain in bacterial MARTX toxins. Protein Sci. 2009;18:856–862. doi: 10.1002/pro.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: causality and therapeutic approaches. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S33–S36. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(09)70014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]