It’s a trajectory that public health and nutrition advocates fear is becoming all too familiar: voluntary approaches that have little effect, followed by government regulatory inaction.

It happened with trans fats and it appears about to happen with salt, the advocates say. Already Health Canada’s Sodium Working Group has signaled that it believes regulations aimed at reducing the amount of salt in prepared foods would be too cumbersome, complex and expensive to implement (CMAJ 2009. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3100). The group is weeks away from releasing a long-overdue national salt reduction strategy that will focus strictly on “voluntary” cutbacks by the food industry.

Yet, Health Canada has been down that path with trans fats.

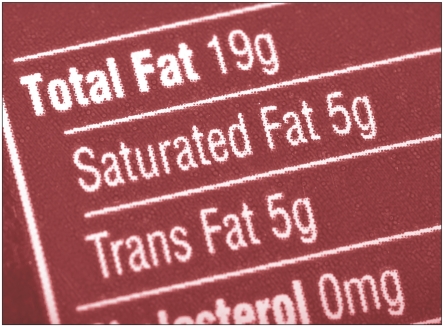

A government task force, comprised of health advocates and industry experts, unanimously recommended the regulation of trans fats. Instead, in 2007, the government gave the food industry two years to voluntarily limit trans fats to 2% of the total fat content in vegetable oils and margarines and 5% in all other foods — or else face regulation.

The deadline for compliance passed in 2009, and while industry has yet to meet the targets, regulation of trans fats is still nowhere on Health Canada’s agenda and Canadians continue to consume harmful levels of trans fats.

In failing to act on the original recommendation of the task force, and in failing to subsequently introduce regulations after voluntary measures proved ineffective, the federal government’s commitment to public health nutrition is called into question, health advocates say.

“It’s as if they’re rolling back the clock to 2004 when the task force was first created,” says Bill Jeffery of the Centre for Science in the Public Interest, a member of both the trans fat task force and the sodium working group.

Health Canada estimates its voluntary trans fat reduction program decreased the average Canadian’s daily intake of trans fats from 5 grams in 2005, or 2% of overall energy, to 3.4 grams in 2008, or 1.4% of energy.

“We’re talking hundreds, possibly thousands, of premature deaths that could have been avoided by taking stronger government action,” he adds. “It leaves one wondering if they have a plan at all.”

Sally Brown, head of the Heart and Stroke Foundation and cochair of the trans fat task force, says “Trans fats are a known health risk, they’re relatively easy to remove from foods, the public is fully supportive of the change, and the task force along with industry categorically recommended regulation.”

Even some sectors of industry, such as restaurants, are “lobbying for regulation because they don’t think it’s fair that some companies are making changes while others are not,” says Brown.

The voluntary program aimed to drop the average Canadian’s consumption of trans fats below two grams per day, or less than 1% of overall energy intake, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

Health Canada estimates the program decreased the average Canadian’s daily intake of trans fats from 5 grams in 2005, or 2% of overall energy, to 3.4 grams in 2008, or 1.4% of energy.

Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq said the results indicated “that further reductions are needed to fully meet the public health objectives and reduce the risk of coronary heart disease” (www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=4436122&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=40&Ses=3).

In April, Health Canada told the House of Commons standing committee on health that the department recognized “the value of a regulatory approach.” But it was quick to qualify that by saying regulation was only “one of the options” being considered to replace the failed voluntary approach.

“I would be somewhat sympathetic if Health Canada said they were considering alternatives to regulation because they had learned in the interim that other means might be more effective. But there’s no indication of what those alternative measures might be,” says Jeffery.

Asked why the government is continuing to ignore the advice of the trans fat task force to regulate, Health Canada media relations officer Christelle Legault said “[We] will continue to analyze the data from the trans fat monitoring program and will identify the most suitable approach required to maintain the progress already made and to further reduce trans fat in the Canadian diet.”

“Over two-thirds of prepackaged foods and foods from family and fast food restaurants have met the trans fats targets,” adds Josee Bellemare, a spokesperson for Aglukkaq.

But Jeffery says Health Canada may be overstating the progress made by industry under the voluntary program. “The evidence indicating trans fat levels have gone down to 1.4% is based on reviews of samples of foods, most of which weren’t measured at two or more points in time. If you’re sampling restaurant fries one year and frozen fries the next, and you notice a difference in trans fat levels, it’s unreasonable to conclude that it’s part of an overall downward trend in the food supply.”

Many Canadians may also be unwittingly consuming excessive trans fat because they may believe regulations are already in place, Jeffery adds. “Health Canada has frequently made the public statement that they have adopted the trans fat task force report recommendations. When I heard that the first time, I thought it must have been a misstatement, but they’ve repeatedly said it and it leaves the impression [regulations have been] implemented.”

The government’s reluctance to regulate trans fat is worrisome to those who believe regulation will be necessary for sodium in the near future. “It’s unfortunate we couldn’t set a precedent,” says Brown.

But several members of the sodium working group suggest that regulation simply isn’t on the agenda.

Mary L’Abbé, vice chair of the sodium working group, calls sodium reduction efforts around the world “works in progress” and told CMAJ in an earlier interview that the food industry “is too diverse” to expect it to comply with mandatory regulations.

Meanwhile, Dr. Kevin Willis, working group member and director of partnerships at the Canadian Stroke Network, says the cost of retooling product lines, the loss of product shelf life, the loss of customers because of changes in product taste, and a lack of alternatives to perform the preservative functions of salt will all act as barriers to voluntary change.

Canada’s dependence on trade with the United States also means any regulation of sodium will have to wait until similar efforts are possible south of the border, says Willis.

In the US, salt has escaped regulation because of a belief that it is safe but the prestigious Institute of Medicine recently urged that mandatory reduction be imposed as voluntary efforts have failed (CMAJ 2010. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.109-3247).

Jeffery says Canadians shouldn’t hold their breath waiting for regulatory action. “It all comes down to how confident you can be that government and industry will follow the advice given; industry has at least made some progress, but in the case of government, I have zero confidence.”

The sodium working group’s strategy, scheduled to be released in July, will rely on industry to meet voluntary targets aimed at cutting the average Canadian’s daily salt intake from an unhealthy 3400 milligrams to 2300 milligrams by 2016.

The strategy will identify voluntary targets for the 10 most sodium-laden food groups, including bakery products, cereals, dairy products, processed meats, snacks, sauces and soups. It will also define timelines for compliance and propose that an independent agency be established to monitor industry progress.