Abstract

Background

Exposure to x-irradiation in early gestation has been shown to disrupt normal thalamo-cortical development in the monkey and thereby model one key feature of the neuropathology of schizophrenia. However, the effect of fetal irradiation on cognitive functions that are vulnerable in schizophrenia, e.g., working memory, has not been examined.

Methods

Four fetally irradiated macaque monkeys (FIMs) and 4 age-matched controls (CONs) were tested as juveniles (12–30 mo) and again as adults (~5 yrs) on Delayed Spatial Response (DR), a working memory task that is dependent on intact prefrontal cortical circuitry.

Results

As juveniles, 7 of 8 monkeys learned DR; one FIM refused to test. Performance in the two groups was not different. As adults, only one FIM achieved criterion on DR. Three of 4 FIMs did not reach criterion at the 0-sec delay interval of the DR task whereas all 4 CONs mastered DR at the maximum tested delay of 10 secs. FIMs completed fewer DR test sessions compared to CONs. In contrast, all FIMs and 3 of 4 CONs learned an associative memory task, Visual Pattern Discrimination.

Conclusions

Fetal exposure to irradiation resulted in an adult-onset cognitive impairment in the working memory domain that is relevant to understanding the developmental etiology of schizophrenia.

Keywords: thalamus, prefrontal cortex, working memory, schizophrenia, neurodevelopment, attention

Mounting epidemiologic evidence suggests that schizophrenia is a disease with origins in neurodevelopment (1–4). Despite the likely prenatal origin of schizophrenia, symptom onset generally is not observed until late adolescence or early adulthood (5), suggesting an interaction between latent brain pathology and developmental processes that unmasks cognitive and behavioral disturbances of the disease (6). Prefrontal cortical dysfunction is a core feature of schizophrenia as patients exhibit thought disorder and are impaired on cognitive tests of working memory (7–9).

We disrupted neurogenesis in early gestation by exposing the developing brain to x-irradiation. We then performed longitudinal cognitive assessment to determine if fetal exposure to irradiation produces a working memory deficit, and if so, whether this deficit is present at young ages or instead emerges with maturation to adulthood.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects

Eight rhesus monkeys, four exposed in utero to x-irradiation (FIMs) as described previously (10) and four sham-irradiated (N=3) or non-irradiated (N=1) controls (CONs), were subjects (Table 1). All animal protocols were approved by Yale’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The monkeys were born naturally at term (~E165), stayed with their mothers until 6 months of age, and then were pair-housed (6) or singly-housed (CON-Vf, FIM-Sf) in the adult colony.

Table 1.

Irradiaton Exposure and Age of Behavioral Testing

| Animal | Sex | DOB | Time in embryonic day (E) and dose of irradiation (in cGy) | Total dose (in cGy) | Age at Testing (in mos) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile DR | Adult DR | Adult VPD | |||||

| FIM-Tm | M | 021901 | E34(50), E36(50), E38(50), E41(50) | 200 | 15–26 | 54–56 | 57–59 |

| FIM-Lf | F | 032301 | E30(50), E33(50), E35(50), E37(50) | 200 | 15–30 | 58–59 | 61–64 |

| FIM-Sf | F | 042701 | E32(50), E34(50), E36(50) | 150 | 16–29 | 58–60 | 60–63 |

| FIM-Bm | M | 052601 | E35(50), E37(50), E38(50) | 150 | 17–29 | 53–59 | 60–61 |

| CON-Mm | M | 032301 | 4 doses ketamine –E29, E32, E34, E36 | 0 | 12–27 | 53–55 | 57–58 |

| CON-Om | M | 042501 | 2 doses ketamine- E34, E36 | 0 | 16–25 | 57–58 | 58–59 |

| CON-Vf | F | 073101 | 3 doses ketamine- E39, E41, E43 | 0 | 13–26 | 56–57 | 60 |

| CON-Jf | F | 081401 | no sham irradiation | 0 | 18–24 | 55–57 | 59–60 |

Behavioral Testing

Delayed Spatial Response (DR) task

Monkeys were tested on manual DR (described in 11) as juveniles (12–30 mo) and as adults (~5 yrs). DR is a working memory task because the position of the bait must remembered through the delay interval and must be updated on a trial-to-trial basis to obtain the reward. Every attempt was made to promote accurate performance. For example, the particular reward used as bait was tailored to the individual monkey’s preference, and baiting of the well was accentuated to ensure that the monkey was watching.

DR was administered in 3 phases. In phase 1, monkeys were habituated to the transport cage and the Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA) and were trained to displace identical plaques covering baited wells. In phase 2, the screen was introduced to institute a memory/delay interval of “0 sec.” However, even the “0 sec” delay produces a momentary gap in which working memory is required to bridge the interval between seeing the baited well and executing the correct response. In phase 3, the delay was incremented by 1-sec intervals to 10 sec as monkeys achieved criterion performance at each interval. Monkeys were required to perform ≥ 90% correct across 100 consecutive trials for 1–5 sec delay intervals and ≥90% correct in 1 session (~30 trials) for 6–10 sec delay intervals. Due to an animal technician’s impending leave of absence; 2 juvenile CONs were more quickly promoted (> 90% correct in 1 session at all intervals), and CON-Jf was tested only to the 4-sec delay. When retested as adults, the 7 monkeys that had successfully performed DR as infants (4 CONs, 3 FIMs) were given 500 consecutive trials to meet criterion in phase 2 (0 sec delay); FIM-Bm, who not perform DR as a juvenile, was allowed 1000 trials to meet the phase 2 criterion.

Visual Pattern Discrimination. (VPD)

All adult monkeys were tested on VPD (as described in 11). VPD is an associative memory task wherein one stimulus (a white “plus sign” on a black background) invariantly signals the availability of the bait/reward and a second stimulus (a white “square” on a black background) is never associated with the reward. Wells were baited and covered with the screen down, out of view of the monkey. The right/left position of the bait was irrelevant and was predetermined by a modified Gellerman series. An intertrial interval of ~10–20 secs was used to approximate the intertrial interval in DR. Monkeys were tested until they met criterion (≥90% across 100 trials).

Statistical analyses

Between-group differences on juvenile DR performance (number of trials to criterion) were tested using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (SPSS v. 14.0) at each of 5 delay intervals (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and 7–8 secs). Group differences in performance on VPD (trials to criterion) were examined using a non-parametric, chi-square approach (SAS PROC NPAR1WAY SAS v. 9.1).

RESULTS

Juvenile DR performance

All 4 juvenile CONs and 3 juvenile FIMs met criterion on DR at the “0 sec” delay in phase 2. FIM-Bm would not engage in the task. All monkeys who mastered phase 2 also successfully completed phase 3 through at least the 8-sec delay interval, except CON-Jf who completed DR at the 4-sec delay interval (see above). The number of trials required for FIMs and CONs to reach criterion on DR did not differ (all p≥ 0.289) at any delay.

Adult DR performance

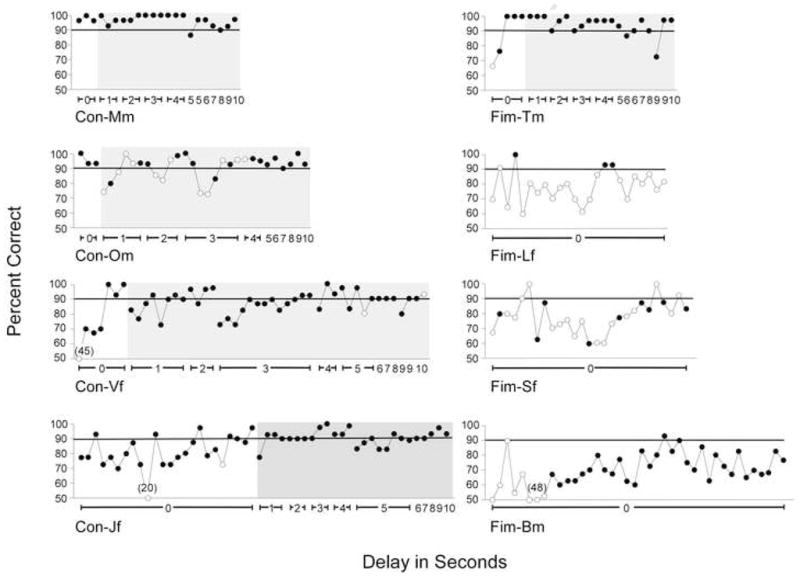

As adults, all 4 CONs mastered DR at all delays (0–10 secs) whereas of the 4 FIMs, only FIM-Tm achieved this goal (Fig. 1). In fact, with the exception of FIM-Tm, the FIM cohort failed DR at its most basic level, i.e., 0-sec delay. Thus, all of the CONs who learned the task as juveniles also learned the task as adults. However, 2 of 3 FIMs who learned the task as juveniles could no longer perform the task as adults. FIM-Bm did not master the task as an adult despite being allowed 1000 trials to meet criterion. FIM-Bm engaged in the task but performed inconsistently even at the 0-sec delay (Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that although FIM-Tm’s performance was indistinguishable from adult CONs, this monkey used positional cueing to perform the task, i.e., he moved his body to the side of the cage corresponding to the position of the baited well. Therefore, this FIM may have been using a motor-based strategy rather than working memory to retain the location of the reward. Statistical comparison of the groups was not possible because only one FIM performed DR as an adult.

Figure 1.

Plots of Individual Test Sessions for Adults Performing DR. Percent correct for each test session of DR is plotted for CONs (left) and FIMs (right). Unshaded areas indicate phase 2 (0-sec) delay trials. Shaded areas indicate test sessions for delays of 1–10 secs (phase 3). Filled circles represent completed test sessions (all 30 trials performed), and open circles indicate incomplete test sessions (< 30 trials completed). Numbers in parentheses indicate percent correct > 50%. Note that FIMs Lf, Sf, and Bm did not meet criterion for performance on DR at the 0-sec delay interval and that performance in these animals was erratic, sometimes ranging above 90% correct but never sustaining this level of performance to reach criterion.

Adult VPD performance

All FIMs mastered VPD in <1000 trials. Surprisingly, FIM-Bm, who would not perform DR as a juvenile and failed DR an adult, achieved the discrimination in only 320 trials. Three CONs acquired VPD in ~200–400 trials. Testing of CON-Jf was stopped after 690 trials when the monkey had attained 60% accuracy. In the 3 CONs and 4 FIMs that reached criterion, the number of trials required did not differ between groups (c2= 0.1250, p= 0.7237).

DISCUSSION

Early gestational irradiation produced a profound cognitive deficit in adulthood in 3 of 4 FIMs. Performance of these monkeys on DR did not reach criterion even at the shortest possible delay, a deficit comparable to that of juvenile monkeys given large prefrontal lobectomies and more severe than deficits in adult monkeys with dlPFC lesions given that FIMs often did not complete testing sessions (12,13). Notably, these same FIMs did not exhibit working memory deficits as juveniles. Of the 3 FIMs that failed to perform DR as adults, 2 had been competent on DR as juveniles at much longer delays (8–9 secs). Failure of the adult FIMs to perform DR even at the most minimal delay is indicative of a severe cognitive deficit since this is an easy task for normal adult monkeys, especially those with prior experience performing the task.

The design of the experiment, i.e. requiring >5 years between experimental manipulation in utero and testing of the animals as adults, precluded having larger numbers of subjects. However, an N ≤4/group has been used in behavioral studies of primates (e.g., 11–14). Moreover, pilot data in one monkey with similar prenatal irradiation exposure buttresses our result as this FIM also showed an age-dependent impairment on DR(15).

Specificity of the cognitive deficit

It is noteworthy that FIMs were proficient on VPD, a task that requires memory for a general association and is comparable in difficulty to mastery of the 0-sec delay of DR but does not tap into the working memory functions of the dlPFC (16). Since FIMs were not impaired on VPD, their impairment cannot be attributed to a generalized deficit in cognition or performance. Indeed, dissociation in performance on the two tasks strongly indicates that cognitive impairment of adult FIMs involved the working memory domain.

Neuroanatomic findings in FIMs

MR neuroimaging of the subjects in this study at 6 mos, 12 mos, 3 yrs, and 5–6 yrs has uncovered widespread brain volume deficits encompassing the thalamus, basal ganglia and cortical gray matter (17). Non-human primate studies have established that the dlPFC mediates mnemonic function as part of a circuit involving other brain structures, including the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and the neostriatum (16,18,19). Fronto-striatal-thalamo-cortical circuitry also has been implicated in impairment of attention and executive processing in schizophrenia subjects (20).

Relevance to the developmental hypothesis of schizophrenia

Prenatal stressors, including fetal exposure to diagnostic x-rays, have been linked to the manifestation of schizophrenia in later life (1–4; R. Gross, Myers-JDC Brookdale Institute, Israel, personal communication). Our findings show that fetal exposure to x-irradiation leads to age-dependent cognitive impairment manifesting only in adulthood. These results are pertinent to the etiopathology of schizophrenia because they demonstrate that disruption of brain development can produce a silent lesion, i.e. one that is not functionally expressed until adulthood.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Heidi Voegeli for testing of the infant monkeys, Ms. Voegeli and Ms. Heather Findlay for assistance in performing the prenatal irradiation exposure, and Dr. Paul Thompson, currently Director of the Methodology and Data Anlaysis Center, Sanford Research, Sioux Falls, SD, for statistical consultation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant MH59329 (LS) and the Washington University Conte Center grant MH071616 (John G. Csernansky, M.D., Program Director).

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE/CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mednick SA, Machon RA, Huttunen MO, Bonett D. Adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to an influenza epidemic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:189–192. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800260109013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Susser ES, Lin SP. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944–1945. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:983–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820120071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollister JM, Laing P, Mednick SA. Rhesus incompatibility as a risk factor for schizophrenia in male adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:19–24. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830010021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown AS, Schaefer CA, Wyatt RJ, Geotz R, Begg MD, Gorman JM, Susser ES. Maternal exposure to respiratory infections and adult schizophrenia spectrum disorders. A prospective birth cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:287–295. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancevski B, Keilp J, Kurzon M, Berman RM, Ortakov V, Harkary-Friedman J, Rosoklija F, et al. Lifelong course of positive and negative symptoms in chronically institutionalized patients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2007;40:83–92. doi: 10.1159/000098488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaum M, Schultz SK. The core symptoms of schizophrenia. Ann Med. 1996;28:525–531. doi: 10.3109/07853899608999116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman-Rakic PS. Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: The relevance of working memory. In: Caroll BJ, Barrett JE, editors. Psychopathology and the Brain (American Psychopathological Association) New York, NY: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S, Holzman PS. Schizophrenics show spatial working memory deficits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:975–982. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820120063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Algan O, Rakic P. Radiation-induced, lamina-specific deletions of neurons in the primate visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1997;38:355–352. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970512)381:3<335::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman HR, Goldman-Rakic PS. Activation of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus by working-memory: A 2-deoxyglucose study of behaving rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4693–4706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-12-04693.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman PS. Functional development of the prefrontal cortex in early life and the problem of neuronal plasticity. Exp Neurol. 1971;32:366–387. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(71)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battig K, Rosvold HE, Mishkin M. Comparison of the effects of frontal and caudate lesions on delayed response and alternation in monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1960;53:400–404. doi: 10.1037/h0047392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond A, Zola-Morgan S, Squire LR. Successful performance by monkeys with lesions of the hippocampal formation on AB and object retrieval, two tasks that mark developmental changes in human infants. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:526–537. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castner SA, Algan O, Rakic P, Goldman-Rakic PS. Two nonhuman primate models of psychosis: Fetal irradiation and amphetamine sensitization. Soc Neurosci Abst. 1996;22:1676. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman-Rakic PS. Circuitry of the prefrontal cortex and the regulation of behavior by representational knowledge. In: Plum F, Mountcastle V, editors. Handbook of Physiology. Vol. 5. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1987. pp. 373–417. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldridge K, Wang L, Harms M, Moffitt AJ, Pope K, Csernansky JG, Selemon LD. A longitudinal study of the emergence of postnatal neuroanatomical abnormalities in non-human primates exposed to irradiation in utero: A neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;35(Suppl1):137. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isseroff A, Rosvold HE, Galkin TW, Goldman-Rakic PS. Spatial memory impairments following damage to the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus in rhesus monkeys. Brain Res. 1982;232:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90613-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman HR, Janas J, Goldman-Rakic PS. Enhancement of metabolic activity in the diencephalon of monkeys performing working memory tasks: A 2-deoxyglucose study in behaving rhesus monkeys. J Cognitive Neurosci. 1990;2:18–31. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1990.2.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morey RA, Inan S, Mitchell TV, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA, Belger A. Imaging frontostriatal function in ultra-high-risk, early, and chronic schizophrenia during executive processing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:254–262. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]