Abstract

Monosialotetrahexosy-1 ganglioside (GM1) has been shown to reduce brain damage induced by cerebral ischemia. The objective of this study is to determine whether GM1 is able to ameliorate hyperglycemia-exacerbated ischemic brain damage in hyperglycemia-recruited areas such as the hippocampal CA3 sub regions and the cingulated cortex. Histologic stainings of Haematoxylin and Eosin, Nissl body, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) and phospho-ERK1/2 were performed on brain sections that has been subjected to 15 minutes of forebrain ischemia with reperfusion of 0-, 1-, 3-, and 6- hours in normoglycemic, hyperglycemic and GM1-pretreated hyperglycemic groups. The results showed that GM1 ameliorated ischemic neuronal injuries in the CA3 area and cingulated cortex of the hyperglycemic animals after ischemia and reperfusion. Immunohistochemistry of phospho-ERK1/2 revealed that the neuroprotective effects of GM1 were associated with suppression of phospho-ERK1/2. The results suggest that GM1 attenuates diabetic-augmented ischemic neuronal injuries probably through suppression of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Keywords: Cerebral ischemia, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, Diabetes, Hyperglycemia, Neuroprotection, Monosialotetrahexosy-1 ganglioside

1. Introduction

Hyperglycemia exacerbates ischemic brain damage with accelerated processes and recruitments of additional ischemic resistant structures through multiple mechanisms (Kamada et al., 2007; Li et al., 1997; Li et al., 2001; Schurr et al., 2001; Muranyi et al., 2005, 2006). One of the proposed mechanisms is increased release of glutamate that results in opening of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) channels, influx of calcium, and activation of biochemical cascades that eventually cause cell death (Kurihara et al., 2004; Li et al., 2001; Terao et al., 2008). Elevated calcium levels of intracellular space through NMDA activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal pathway (Haddad, 2005; Hu et al., 2000; Kurihara et al., 2004). Activation of MAPK may be associated to increased brain damage caused by ischemic stroke under hyperglycemic conditions since phosphorylation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinases-1 and 2 (ERK1/2) are increased in hyperglycemia-recruited damage areas (Farrokhnia et al., 2005; He et al., 2003; Kurihara et al., 2004; Li et al., 2000) and inhibition of MAPK, including ERK1/2 and JNK, signaling pathways reduced the ischemic brain damage under both normo- or hyperglycemic conditions (Guan et al., 2005; Namura et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2006;).

GM1 is the major type of ganglioside protein family that is a component of cell membrane in most mammals, (Marconi et al., 2005). GM1 exists in the nervous system, particularly around synapses and acts as a membrane stabilizer blocking neuronal cell death pathways (Sohn et al., 2006). GM1 has been used for treating disorders of the central nervous system due to its permeability through the blood-brain barrier (Marconi et al., 2005; Kwak et al., 2005). GM1 has been shown to reduce brain edema, to stabilize neuronal cell membranes, to activate Na+-K+-ATP and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP pumps, to inhibit influx and intracellular accumulation of Ca2+ (Sohn et al., 2006), and to reduce ischemic brain damage under normoglycemic conditions. However, it is not known whether GM1 is capable of protecting brains from hyperglycemia-exacerbated ischemic neuronal death. The objectives of this study are to determine whether GM1 reduces neuronal death after brain ischemia in hyperglycemic subjects, and whether GM1 exerts any effects on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in hyperglycemic ischemic rats. In order to achieve the goals, rats were subjected to 15 minutes of transient forebrain ischemia with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced hyperglycemia. Animals were pretreated with GM1 and histopathologic outcomes as well as phosphotylation of ERK1/2 were examined after after 1-, 3-, and 6- hours of reperfusion in the ischemic resistant hippocampal CA3 area and cingulated cortex.

2. Results

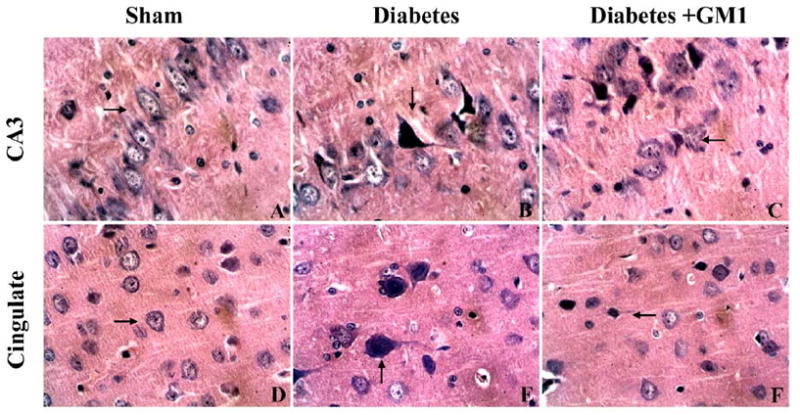

2.1. Histopathology

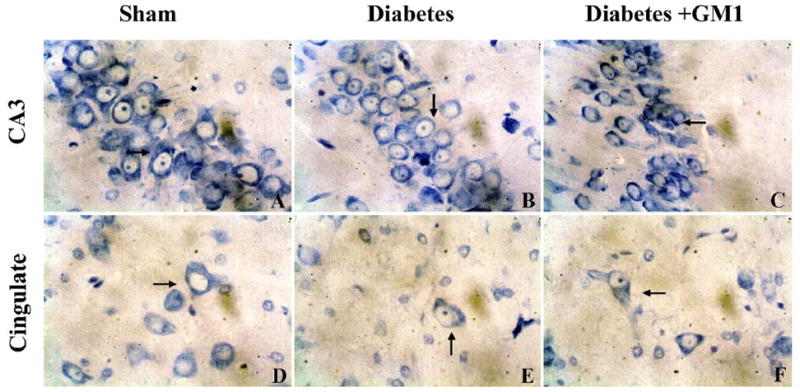

As expected there was no neuronal death observed in the sham-operated animals in the normoglycemic group. Mild brain edema, cellular swollen, reticulum formation of chromatin, and disappearance of nucleolus were observed in few scattered neurons in both the hippocampal CA3 and cingulate cortex at 1 hour reperfusion. At 3 hours of recovery, cytoplasmic vaculization and karyopyknotic neurons with triangular shape were observed in about 10% of the neurons. At reperfusion of 6 hours, number of dead neurons increased. In the diabetic group, brain tissue edema and number of neurons with above described alterations were increased compared with normoglycemic animals at identical reperfusion stages in both the CA3 and cingulated cortex areas. These pathological changes progressed along with the reperfusion time. When the hyperglycemic ischemic animals were treated with GM1, the number of damaged neurons was significantly decreased at reperfusions of 3- and 6- hours in the hippocampal CA3 and the cingulate cortex. A set of representative photomicrographs from the two structures at 3 hours of reperfusion was given in Fig. 1 and the summarized results form the CA3 and cingulated cortex were presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, respectively.

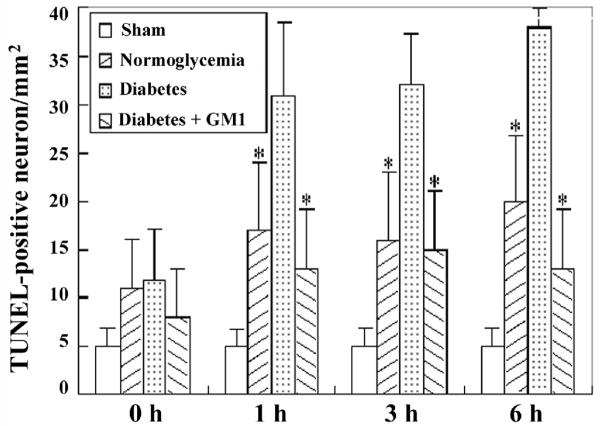

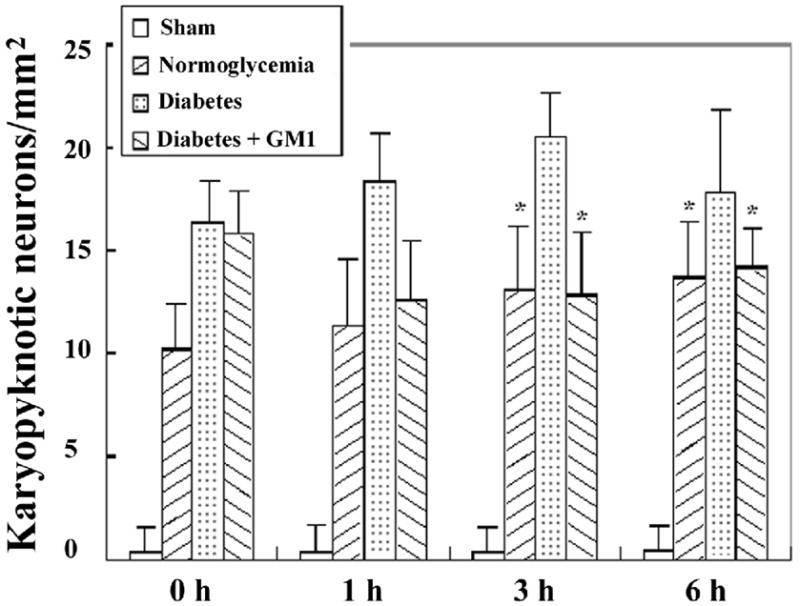

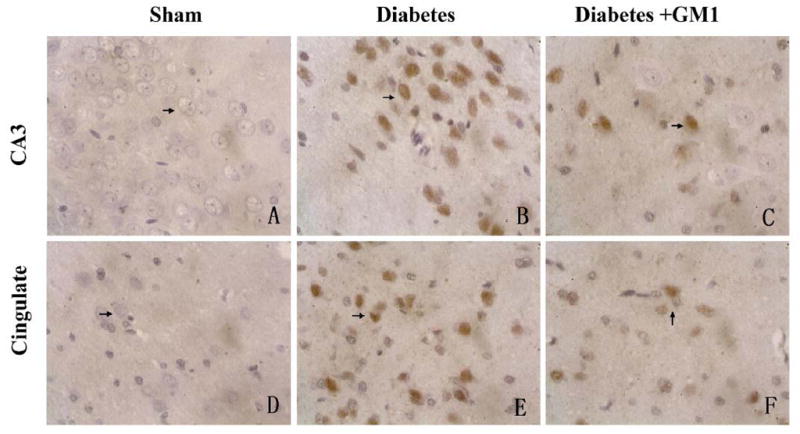

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs showing histological appearance of the hippocampal CA3 (upper panel) and cingulate cortex (lower panel) at 3 hours of reperfusion after 15 minutes of forebrain ischemia. Sections were from sham-operated controls (A, D), diabetic ischemia plus 3 hours of recovery (B, E), and GM1-treated diabetic ischemia (C, F) at 3 hours of reflow. Arrows indicate damaged neurons. There was no obvious lesion in the hippocampal CA3 (upper panel) and cingulate cortex (lower panel) in the sham-operated rats (A, D). The neuronal damage, characterized by a shrunken cell body in triangular shape with condensed nucleus, was observed in the hippocampal CA3 and cingulate cortex of the diabetic rats (B, E). A few shrunken neurons with condensed nuclei were also observed in the GM1 treated rats (C, F). Haematoxylin & Eosin-stained. 400×

Fig. 2.

Bar graph showing the number of karyopyknotic neurons in the CA3 area in the four groups of animals. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. * P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

Fig. 3.

Bar graph showing the number of karyopyknotic neurons in the cingulated cortex in the four groups of animals. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. * P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

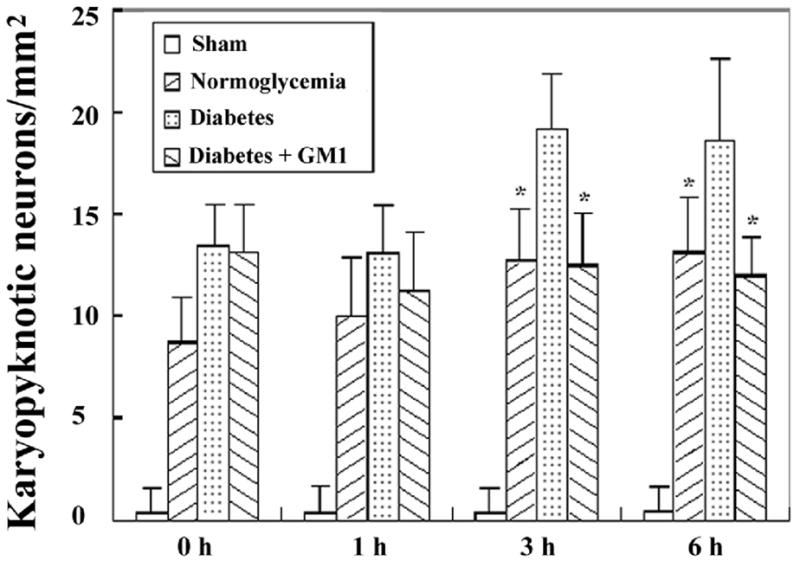

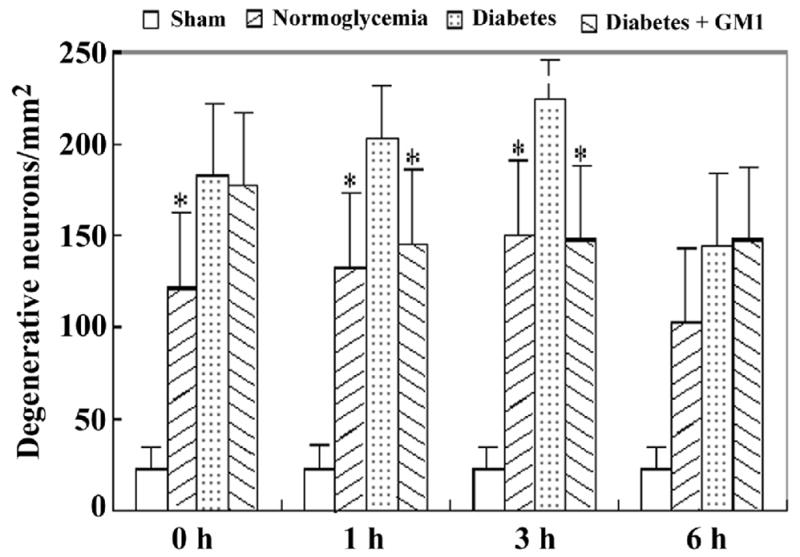

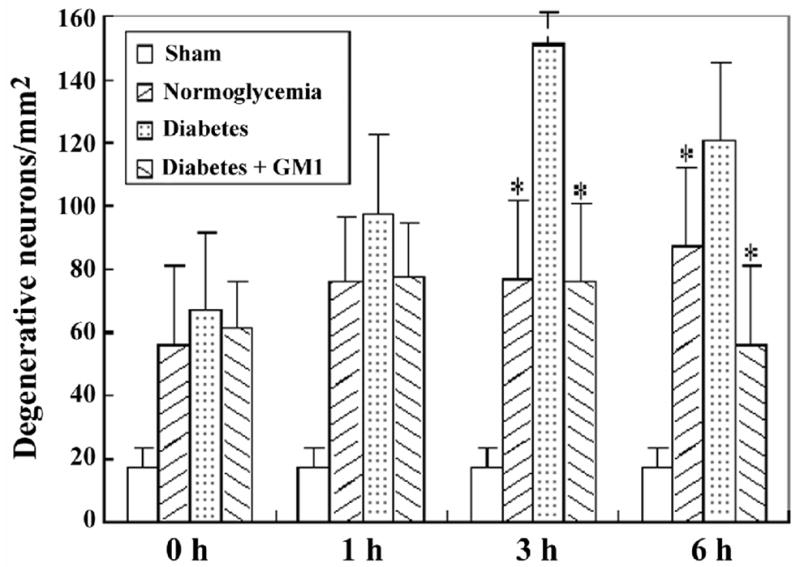

2.2. Neuron degeneration

The degenerative neurons, as defined by more than 50% decreased Nissl body staining were observed in all the ischemic groups at reperfusions of 0-, 1-, 3- and 6- hours. The number of degenerative neurons were higher in the diabetic group than in the normoglycemic groups in the hippocampal CA3 area at 3 hours of recirculation (Fig. 4). Similarly, the number of degenerative neurons in the cingulated cortex was higher in the diabetic animals than in the normoglycemic group. Treatment with GM1 in diabetic ischemic rats significantly lowered the numbers of degenerative neurons in the CA3 area at 1- and 3- hours and in the cingulated cortex at reperfusions of 3- and 6- hours, as compared with the diabetic ischemic animals. A set of photomicrograph from the CA3 area and cingulated cortex at 3 hours of reperfusion was given in Fig. 4 and summarized cell counts at various reperfusion times were given as bar graphs for the CA3 (Fig. 5) and the cingulated cortex (Fig. 6).

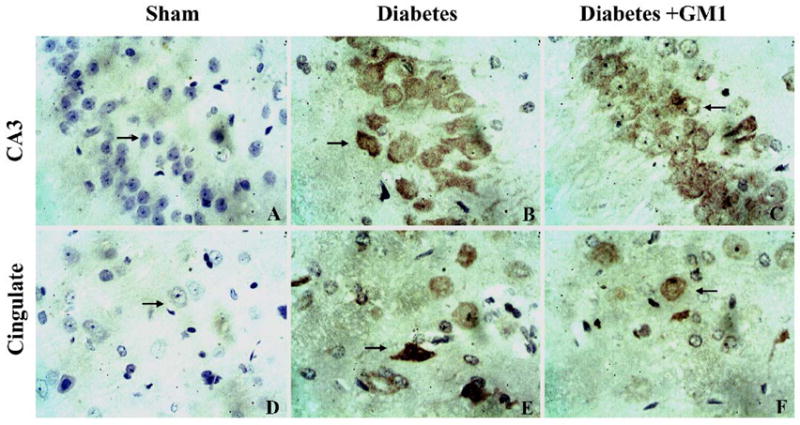

Fig. 4.

Photomicrographs showing degenerative neurons in the hippocampal CA3 (upper panel) and the cingulated cortex (lower panel) at 3 hours of reperfusion. There was no obvious decrease of Nissl body staining in neurons in the hippocampal CA3 (A) and cingulated cortex of the sham-operated rats (D). Degenerated neurons were found in the hippocampal CA3 (B) and cingulated cortex (E) in the diabetic rats. The numbers of the degenerative neurons in the same areas were decreased in the GM1 treated rats (C, F). Pischingert staining, 400×

Fig. 5.

Bar graph showing the number of degenerative neurons in the CA3 area in the four groups of animals. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. * P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

Fig. 6.

Bar graph showing the number of degenerative neurons in the cingulated cortex in the four groups of animals. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1 hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. *P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

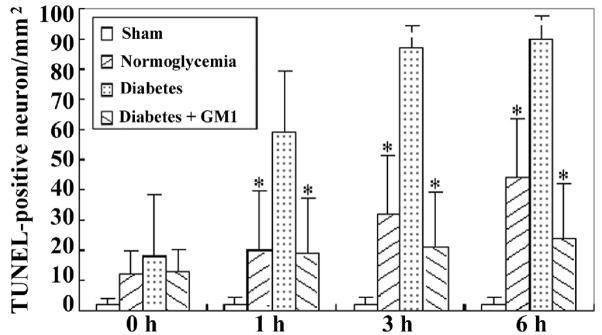

2.3. TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was performed to define neuronal DNA damage in the current study. TUNEL positive neurons were observed in the hippocampal CA3 and cingulated cortex of the normoglycemic as well as diabetic rats at reperfusions of 0-, 1-, 3- and 6- hours (Fig. 7). In the hippocampal CA3 at reperfusions of 3- and 6- hours and in the cingulated cortex at all the reperfusion time points, the number of TUNEL positive neurons was significantly increased in the diabetic group than that in the normoglycemic group. GM1 treatment in diabetic animals significantly reduced the number of TUNEL positive neurons at 3- and 6- hours of reperfusion in the hippocampal CA3 (Fig. 8) and in the cingulated cortex (Fig. 9) at 1-, 3- and 6- hours of reperfusion, compared to non-treated diabetic group.

Fig. 7.

A set of representative photomicrograph showing TUNEL-positive neurons in the hippocampal CA3 (upper panel) and the cingulated cortex (lower panel) at 3 hours of reperfusion. There were no TUNEL-positive neurons observed in sham-operated rats (A, D). The TUNEL-positive neurons in the hippocampal CA3 and the cingulated cortex were found in the diabetic rats (B, E). The numbers of TUNEL-positive neurons in the same areas were decreased in the GM1 treated rats (C, F). The sections were slight counterstained with haematoxylin. Dark brown color indicates TUNEL positive stain (arrows). 400×

Fig. 8.

Number of TUNEL-positive neurons in the CA3. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1 hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. *P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

Fig. 9.

Number of TUNEL-positive neurons in the cingulated cortex. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1 hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. *P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

2.4. Levels of Phospho-ERK1/2

In the CA3 area (Fig. 10 upper panel and Fig. 11), number of phospho-ERK1/2 positive neurons started to increase at reperfusion of 1 hour and peaked at reperfusion of 6 hours. The number increased to more than double in diabetic animals at reperfusions of 1-, 3-, and 6- hours compared to normoglycemic ischemic animals. Treatment with GM1 significantly reduced the number of phospho-ERK1/2 positive neurons at reperfusions of 3- and 6- hours (Fig. 11)

Fig. 10.

Photomicrographs depicting positive phospho-ERK1/2 stained neurons in the hippocampal CA3 (upper panel) and cingulated cortex (lower panel) at 3 hours of reperfusion. There were no obvious phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactive neurons in the sham-operated rats (A, D). The phosph-ERK1/2 positive neurons were found in the hippocampal CA3 and cingulated cortex in the diabetic rats (B, E). The apparent phosph-ERK1/2 positive neurons in the same areas were also given in the GM1 treated rats (C, F). DAB visualization. Sections were lightly counterstained by haematoxylin. 400×

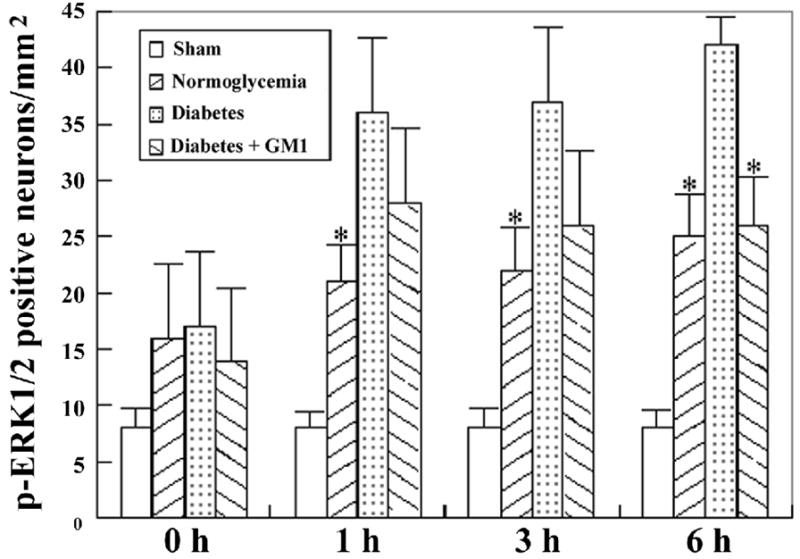

Fig. 11.

Number of phospho-ERK1/2 stained neurons in the CA3. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1 hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. *P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

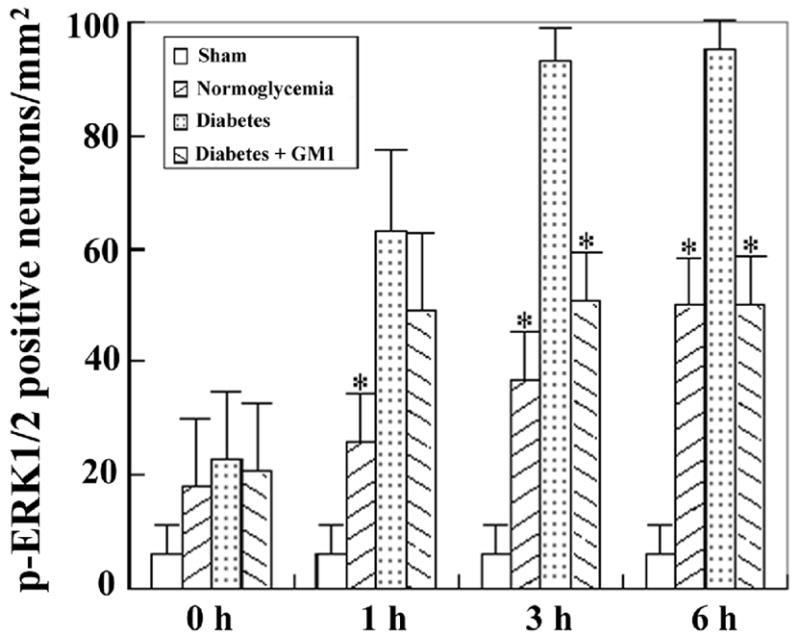

In the cingulated cortex (Fig. 8 lower panel and Fig. 12), a few scattered, anti-phospho-ERK1/2 weakly stained cells were found in the sham-operated rats (Fig. 12). The number of phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactive cells increased gradually in normoglycemic animals after 1 hour of reperfusion and reach to peak level at 6 hours of reperfusion. Compare to normoglycemic groups, diabetic ischemia further increased the number of phospho-ERK1/2 positively stained neurons at 1-, 3-, and 6- hours of reperfusion in the cingulated cortex. GM1 treatment to diabetic animals reduced the number of ERK1/2 positive cells at 6 hours of reperfusion to the levels observed in the normoglycemic groups (Fig. 12)

Fig. 12.

Number of phospho-ERK1/2 stained neurons in the cingulated cortex. A, ischemia with reperfusion of 0 hour; B, 1 hour; C, 3 hours; and D, 6 hours. *P<0.05, vs. diabetic group.

3. Discussion

The results showed that diabetic hyperglycemia enhanced the numbers of dead neurons as defined by the Haematoxyllin and Eosin staining, increased the number of degenerative neurons as measured by more than 50 % deduction of Nissl body staining, augmented DNA fragmentation as characterized by the TUNEL immunolabeling and elevated the levels of phopho-ERK1/2 as assessed by immunohistochemistry in the hippocampal CA3 subregion and in the cingulated cortex after a 15 minutes of transient forebrain ischemia. These results are consistent with previous publications (Li et al., 1998; Li et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2007), confirming that preischemic hyperglycemia exacerbates brain damage incurred after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Our results further revealed that administration of GM1 significantly reduced the number of dead, degenerative, DNA fragmented and phosph-ERK1/2 positively stained neurons in the CA3 and cingulated cortex after 3- and 6- hours of reperfusion.

Gangliosides are widely distributed in the plasma membranes of all vertebrate tissues (Marconi et al., 2005). They are involved in the induction of cell differentiation, proliferation and signal transduction. Studies have shown that GM1 reduces the effluxes of glutamate, aspartate and glycine from the cerebral cortex after transient cerebral ischemia in rats (Kwak et al., 2005; Oliveira and Langone, 2000; Hashiramoto et al., 2006; Ledeen et al., 2004), protects neurons from neurodegeneration, lessens cognitive dysfunction incurred after cerebral ischemia in vivo and ameliorates excitotoxic neuronal death in vitro (Ledeen et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2001). The mechanism of the neuroprotective effects of GM1 is not fully understood. One proposed mechanism is that excessive release of glutamate in the synapse activates NMDA receptor (NMDAR), which subsequently increases the influx of calcium to intracellular space. Calcium triggers activation of various lipases, proteases, DNases and eventually results in cell death. It is well known that excitation of NMDAR serves a prominent role in the pathophysiological process of cerebral ischemia (Runden-Pran et al., 2005). Consistent with this view, NMDAR antagonists attenuate the Ca2+ influx and reduce neuronal death elicited by glutamate exposure and NMDA agonists (Yin et al., 2005). GM1 may reduce the release of glutamate, thereby, inhibits the activation NMDAR and blocks the cascade reactions leading to cell death (Xie et al., 2004). In addition to its effects on glutamate-NMDA-calcium system, GM1 also has been shown to protect Na+-K+-ATPase activity, to enhance the expression of HSP70, TGF-β and FGFR1 (Zhu et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2005), and to promote neuronal cell maturation and neuritogenesis (Wu et al., 2004). Therefore, GM1 may also exert its protective effects through modulating cell proliferation and signal transduction pathways.

MAPK is one of the important signal pathways that regulate cell proliferation. Previous studies have demonstrated that hyperglycemia markedly increased phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 in the cingulated cortex and hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus areas, structures that are recruited and exacerbated by hyperglycemia when subjected a transient forebrain ischemia (Li et al., 2001; Krupinski et al., 2005; Kurihara et al., 2004). While increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 may promote cell survival by increasing cell proliferation in vitro, inhibition of the ERK1/2 has been linked to decrease neuronal cell death after transient focal cerebral ischemia under normoglycemic conditions and after transient forebrain ischemia under hyperglycemic conditions (Namura et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2006). In this study, we observed that GM1 treatment significantly suppressed the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, a critical member in the MAPK family. Thus, the numbers of phospho-ERK1/2 positively stained neurons in the hippocampal CA3 area and in the cingulated cortex of the GM1-treated hyperglycemic ischemic animals were significantly decreased compared to hyperglycemic ischemic animals without GM1 treatment. This suppression of ERK1/2 was associated with ameliorated neuronal damage in these brain regions. These results, together with our previously published data, suggest that GM1 reduces hyperglycemia-exacerbated ischemic brain damage by inhibition of ERK1/2 activity. It is likely that enhanced acidosis during hyperglycemic ischemia activates ERK1/2, which subsequently phosporylates Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs). Phosphorylation of NHEs causes sodium accumulation in neurons and subsequently triggers calcium overload through the reverse mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchange (Luo et al., 2007; Luo and Dun 2007). It is also possibly that hyperglycemia stimulates the glutamate-NMDAR-calcium cascade after ischemia and then increased intracellular calcium activates MAPK pathways that contributed to the hyperglycemia-enhanced ischemic brain damage. GM1 ameliorated hyperglycemia-aggravated ischemic brain damage by inhibiting the activation of NMDAR and subsequently the suppression of phospho-ERK1/2. The finding showing that hyperglycemic ischemia increased glutamate levels (Li et al., 1999) and inhibition of ERK1/2 decreased hyperglycemia-enhanced ischemic brain damage (Zhang et al., 2007) lend support to this notion.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Animals and reagents

Male Sprague-Dewley rats with a mean body weight of 240–350g were provided by the animal center for medical experiment at Ningxia Medical University. All animal use and procedures were in strict accordance with the Chinese Laboratory Animal Use Regulations. Efforts were made to minimize animal stress and to reduce the number of rats used for this study. GM1 compound (Sigma), monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signal), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma), the TUNEL (Zymed), and STZ (Calbiochem, Germany), were purchased from Boster Biotechnology Co. (Wuhan, China).

4.2. Animal treatments

Diabetic hyperglycemia was induced by injection of STZ (55 mg/kg) through the tail vein. Rats typically developed hyperglycemic states 2–3 days after the injection. Animals with serum glucose content of 16.7 mmol/L or above were defined as hyperglycemic and used 7 days after STZ injection. For GM1-treated hyperglycemic group, rats were injected intraperitoneally with GM1 (15 mg/kg) 20 minutes before the introduction of ischemia. Same volume of 0.9% normal saline was injected to vehicle control animals.

4.3. Ischemia Model and experimental groups

Forebrain brain ischemia was introduced under anesthesia by bilateral clamping of the common carotid arteries and exsanguinations for 15 minutes, maintaining blood pressure at 40 to 50 mmHg and yielding an isoelectric EEG. Circulation was resumed by re-infusing the shed blood and by releasing the ligatures placed around the carotid arteries. Rats used for 1 hour of reperfusion were maintained under anesthesia for whole post-ischemia period. Rats for reperfusion of 3- and 6- hours were disconnected from anesthesia at the end of 15 minutes ischemia and re-anesthetized for reperfusion at 3- and 6 hours later.

Rats were randomly divided into four groups, 1) sham-operated non-ischemic control group (n=5); 2) normoglycemic ischemic group (n=5); 3) diabetic ischemic group (n=20); and 4) GM1-treated diabetic ischemic group (n=20). Animals in the two diabetic groups (groups 3 and 4) were further divided into 4 sub-groups, namely 15 minutes ischemia with 0-, 1-, 3-, and 6- hours of reperfusion (n=5 in each subgroup). At the pre-determined time points, animals were euthanized and their brains were removed and dissected at fissura longitudinalis and transversa cerebri, then one half of the brain fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brain samples were processed and embedded in paraffin, and then were sectioned at 5 micrometer intervals using a microtome. The sections were later used for histologic, TUNEL and immunohistochemistry studies.

4.4. Pischingert staining

After 10 minutes incubation at room temperature in methylene blue, the sections were washed in PBS (pH 4.6) until the Nissl bodies become clear. The sections were then incubated with 4% ammonium molybdate buffer for 5 minutes.

4.5. TUNEL staining

In situ detection of DNA fragmentation was performed using TUNEL staining according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Zymed). In brief, after being washed 3 times in Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), sections were treated with 2% H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were then incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme solution at 37°C for 1 hour. Sections were dipped in 300 mM NaCl and 30 mM sodium citrate solution for 15 minutes at room temperature to terminate the reaction. After sections were washed 3 times in Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) and subsequently blocked with PBS (pH 7.4) containing 10% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100, biotinylated-16-dUTP was visualized by the avidin-biotin method with 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) tetrahydrochloride and 0.005% H2O2.

4.6. Immunohistochemistry

Sections were treated with 3% H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections which were merged in citrate solution was briefly heated in a microwave oven to retrieve antigen before nonspecific binding sites were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS/0.2% TX-100 for 30 min. After incubation with the primary antibody (1:400 dilution) at 4°C overnight. The sections were incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody, an avidin-biotin complex conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The slides were displayed with DAB and counter-stained with haematoxylin. The sections were coverslipped, images were captured and analyzed with computer imagine analysis system (Zeiss LSM5 Image Examiner software).

Brain damage in the hippocampal CA3 and the cingulated cortex, two structures that resistant to ischemic brain damage under normoglycemic conditions but would be recruited to the damage process under hyperglycemic conditions, were examined. Neurons with a reduction of Nissl body to 50% of control values was considered as degenerative neurons. Positive TUNEL staining termed as DNA fragmentation. Number of dead, degenerative, and TUNEL positive neurons were counted with computer imagine analysis system (Zeiss LSM5 Image Examiner software) and presented as numbers per square millimeter.

4.7. Statistical analysis

The values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were made by Student t-test. Statistical significance was determined as P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (30560044) to JZZ and by a grant from National Institute of Health (7R01DK075476) to PAL

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DAB

3,3′-diaminodbenzidine

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinases-1 and 2

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- MG1

Monosialotetrahexosy-1 ganglioside

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Farrokhnia N, Roos MW, Terent A, Lennmyr F. Differential early mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in hyperglycemic ischemic brain injury in the rat. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35:457–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan QH, Pei DS, Zhang QG, Hao ZB, Xu TL, Zhang GY. The neuroprotective action of SP600125, a new inhibitor of JNK, on transient brain ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal death in rat hippocampal CA1 via nuclear and non-nuclear pathways. Brain Res. 2005;1035:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad JJ. N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways: a revolving neurochemical axis for therapeutic intervention? Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:252–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiramoto A, Mizukami H, Yamashita T. Ganglioside GM3 promotes cell migration by regulating MAPK and c-Fos/AP-1. Oncogene. 2006;20:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He QP, Ding C, Li PA. Effects of hyperglycemic and normoglycemic cerebral ischemia on phosphorylation of c-jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003;49:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Liu CL, Park DJ. Alteration of MAP kinase pathways after transient forebrain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1089–1095. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, Chan PH. Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke. 2007;38:1044–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258041.75739.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupinski J, Slevin M, Badimon L. Citicoline inhibits MAP kinase signalling pathways after focal cerebral ischaemia. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:1067–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-7201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara J, Katsura K, Siesjo BK, Wieloch T. Hyperglycemia and hypercapnia differently affect post-ischemic changes in protein kinases and protein phosphorylation in the rat cingulate cortex. Brain Res. 2004;995:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak DH, Kim SM, Lee DH, Kim JS, Kim SM, Lee SU, Jung KY, Seo BB, Choo YK. Differential expression patterns of gangliosides in the ischemic cerebral cortex produced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Mol Cells. 2005;20:354–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeen RW, Wang J, Lu Z, Wang Y, Meyenhofer MF, Wu G. Heightened kainate-induced seizures in ganglioside-deficient (KO) mice: function of GM1 in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J Neurochem. 2004;90 (Suppl 1):90. [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li PA, He QP, Ouyang YB, Siesjö BK. Effects of streptozotcin-induced hyperglycemia on brain damage following transient ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:117–128. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PA, Siesjö BK. Role of hyperglycaemia-related acidosis in ischaemic brain damage. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;161:567–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PA, He QP, Ouyang YB, Hu BR, Siesjo BK. Phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase after transient cerebral ischemia in hyperglycemic rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:127–135. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PA, Rasquinha I, He QP, Siesjo BK, Csiszar K, Boyd CD, MacManus JP. Hyperglycemia enhances DNA fragmentation after transient cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:568–576. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PA, Shuaib A, Miyashita H, He QP, Siesjo BK. Hyperglycemia enhances extracellular glutamate accumulation in rats subjected to forebrain ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31:183–192. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Kintner DB, Shull GE, Sun D. ERK1/2-p90RSK-mediated phosphorylation of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1: a role in ischemic neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 2007;28:2874–2884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Sun D. Physiology and pathopahysiology of Na+/H+ exchange isoform 1 in the central nervous system. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:205–215. doi: 10.2174/156720207781387178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi S, De Toni L, Lovato L, Tedeschi E, Gaetti L, Acler M, Bonetti B. Expression of gangliosides on glial and neuronal cells in normal and pathological adult human brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;170:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi M, He QP, Fong KS, Li PA. Induction of heat shock proteins by hyperglycemic cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;139:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namura S, Iihara K, Takami S, Nagata I, Kikuchi H, Matsushita K, Moskowitz MA, Bonventre JV, Alessandrini A. Intravenous administration of MEK inhibitor U0126 affords brain protection against forebrain ischemia and focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11569–11574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181213498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi M, Li PA. Hyperglycemia increases superoxide production in the CA1 pyramidal neurons after global cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AL, Langone F. GM-1 ganglioside treatment reduces motoneuron death after ventral root avulsion in adult rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;293:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runden-Pran E, Tanso R, Haug FM, Ottersen OP, Ring A. Neuroprotective effects of inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, P2X receptors and the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade: a quantitative analysis in organotypical hippocampal slice cultures subjected to oxygen and glucose deprivation. Neuroscience. 2005;136:795–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A, Payne RS, Miller JJ, Tseng MT. Preischemic hyperglycemia-aggravated damage: evidence that lactate utilization is beneficial and glucose-induced corticosterone release is detrimental. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:782–789. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn H, Kim YS, Kim HT, Kim CH, Cho EW, Kang HY, Kim NS, Kim CH, Ryu SE, Lee JH, Ko JH. Ganglioside GM3 is involved in neuronal cell death. FASEB J. 2006;20:1248–1250. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4911fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao S, Yilmaz G, Stokes KY, Russell J, Ishikawa M, Kawase T, Granger DN. Blood cell-derived RANTES mediates cerebral microvascular dysfunction, inflammation and tissue injury following focal ischemia-reperfusion. Stroke. 2008;39:2560–2570. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Lu Z, Xie X, Ledeen RW. Susceptibility of cerebellar granule neurons from GM2/GD2 synthase-null mice to apoptosis induced by glutamate excitotoxicity and elevated KCl: rescue by GM1 and LIGA20. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:303–311. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000046273.68493.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Lu ZH, Wang Y, Xie X, Meyenhofer MF, Ledeen RW. Enhanced susceptibility to kainite-induced seizures, neuronal apoptosis, and death in mice lacking gangliotetraose gangliosides: protection with LIGA 20, a membrane-permeant analog of GM1. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11014–11022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3635-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Xie X, Lu Z, Ledeen RW. Cerebellar neurons lacking complex gangliosides degenerate in the presence of depolarizing levels of potassium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:307–312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011523698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Wu G, Ledeen RW. C6 cells express a sodium-calcium exchanger/GM1 complex in the nuclear envelope but have no exchanger in the plasma membrane: comparison to astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:363–375. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin XH, Zhang QG, Miao B, Zhang GY. Neuroprotective effects of preconditioning ischaemia on ischaemic brain injury through inhibition of mixed-lineage kinase 3 via NMDA receptor-mediated Akt1 activation. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1021–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JZ, Jing L, Guo FY, Ma Y, Wang YL. Inhibitory effect of ketamine on phosphorylation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 following brain ischemia and reperfusion in rats with hyperglycemia. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2007;59:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JZ, Jing L, Ma AL, Wang F, Yu X, Wang YL. Hyperglycemia increased brain ischemia injury through extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Pathol Res Prac. 2006;202:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YH, Ma TM, Wang X. Gene transfer of heat-shock protein 20 protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat hearts. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:1193–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]