Abstract

ER quality control consists of monitoring protein folding and targeting misfolded proteins for proteasomal degradation. ER stress results in an unfolded protein response (UPR) that selectively upregulates proteins involved in protein degradation, ER expansion, and protein folding. Given the efficiency in which misfolded proteins are degraded, there likely exist cellular factors that enhance the export of proteins across the ER membrane. We have reported that translocating chain-associated membrane protein 1 (TRAM1), an ER-resident membrane protein, participates in HCMV US2- and US11-mediated dislocation of MHC class I heavy chains (Oresic, K., Ng, C.L., and Tortorella, D. 2009). Consistent with the hypothesis that TRAM1 is involved in the disposal of misfolded ER proteins, cells lacking TRAM1 experienced a heightened UPR upon acute ER stress, as evidenced by increased activation of unfolded protein response elements (UPRE) and elevated levels of NF-κB activity. We have also extended the involvement of TRAM1 in the selective degradation of misfolded ER membrane proteins Cln6M241T and US2, but not the soluble degradation substrate α1-antitrypsin nullHK. These degradation model systems support the paradigm that TRAM1 is a selective factor that can enhance the dislocation of ER membrane proteins.

Keywords: TRAM1, ERAD, ER stress, UPR, dislocation

Introduction

An overburden of the ER polypeptide load induces ER stress, leading to the activation of a UPR. The UPR is triggered through ER-resident UPR sensors PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-responsive element 1 (IRE1), by eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF6 cleavage, and X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) splicing, respectively [1]. This leads to a translational shut-down to limit ER protein expression, an increase in chaperones to assist in protein folding, and a concomitant increase in components of the degradation machinery to alleviate the burden of misfolded ER proteins [2, 3]. A UPR is observed in professional secretory cells [4, 5], upon expression of ER proteins encoding mutations that render them improperly folded [6, 7] and flavivirus infection [8, 9]. Therefore, understanding ER stress has implications for delineating cellular metabolism, human diseases, as well as pathogenic manipulation of host factors.

One aspect to consider in examining ER stress is the role played by factors involved in the dislocation of polypeptides across the ER bilayer, a process by which ER-resident polypeptides are extracted from the ER and into the cytosol. Polypeptides destined for dislocation must first be recognized by chaperones as misfolded and subsequently exported through the dislocation pore into the cytosol [10]. The identity of the dislocation pore has yet to be definitively resolved: candidates include a multimeric complex consisting of multispanning proteins Derlin-1, -2, and -3 [11-13], as well as Sec61α [14, 15], the main component of the translocon. Once at the dislocation pore, the AAA ATPase p97, with its cofactors Ufd1 and Npl4, provides the force to extract the polypeptide across a membrane bilayer [16]. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes such as Ubc6 and Ubc7 [17, 18], E3 ligases such as Hrd1 [19] and gp78 [20, 21], and deubiquitinating enzymes such as ataxin-3 [22], USP19 [23] and YOD1 [24] function in the ubiquitinating and de-ubiquitinating processes that accompany polypeptide extraction.

Proteins known to be involved in ER-associated degradation (ERAD) such as Der1, Hrd1/Der3, Hrd3, and PER100 were found to be upregulated during a UPR in a genomic analysis in yeast cells [2]. Yeast strains lacking these genes individually showed an increase in up to two-fold UPRE-GFP over wt cells under normal growth conditions. The gene encoding PER100 has sequence homology to a Yarrowia lipolytica gene (SLS1) that encodes a protein physically associated with the translocon [25]. The translocon-associated protein complex (TRAP) is another example of a protein involved in polypeptide processing [26] later shown to be upregulated upon a UPR and required for disposal of a soluble ER degradation substrate [27].

In this study, we addressed the role TRAM1, a protein involved in translocation of nascent polypeptides [28] and the dislocation of a type I membrane protein under viral influences [29], during an ER stress response. We examined if the presence or absence of TRAM1 had any effect on the UPR during acute ER stress, and determined that cells lacking TRAM1 were in fact hypersensitive in their stress response. The data demonstrate that a lack of TRAM1 creates an environment in which the extraction of ER degradation substrates is limited, thereby potentiating a UPR. In addition, the data demonstrate that TRAM1 participates in the selective disposal of ER membrane proteins.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, antibodies, and protein analysis

U373 and HEK 293T cells were maintained in DMEM as described [30]. Cln6wt, Cln6M241T, and α1ATnullHK were introduced into U373vector and U373shTRAM1-R2 cells by retroviral transduction as previously described [31]. Anti-TRAM1 and anti-US2 serum were raised as described [32]. Anti-PDI serum was a kind gift from Dr. H. Ploegh (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). Anti-calnexin antibody (AF8 [33]) was a kind gift from Dr. M. Brenner (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA). The monoclonal antibody to the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (12CA5 [34]) was hybridoma-purified. Antibodies to BiP, ubiquitin, GFP, GAPDH, and α1-antitrypsin were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories, Cell Signaling Technology, Millipore, Chemicon, and Sigma respectively. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses were performed as described [32]. TRAM1 knockdown cell lines using shRNA constructs against various regions of TRAM1 were previously described [29]. The respective plasmid constructs (1μg of plasmid unless otherwise noted) were transiently transfected using a lipid-based protocol (Lipofectamine 2000, Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's guidelines.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the Stratagene Absolutely RNA RT-PCR miniprep kit to yield ≥1μg RNA. qRT-PCR was then performed by the MSSM Quantitative PCR Shared Research Facility [35]. Samples were measured against housekeeping genes GAPDH, β-actin, rps11, and tubulin.

GFP assay

Twelve hours post-transfection with a plasmid encoding the UPRE promoter [36, 37] that drives the expression of GFP were treated with or without thapsigargin. Fluorescence was read using a Beckman Coulter DTX880 Multimode Detector.

Luciferase assay

Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the firefly luciferase reporter gene under the control of an NF-κB-responsive promoter [38] (0.3μg) and the Renilla luciferase reporter gene under the control of the HSV thymidine kinase promoter, as well as the respective plasmid. Luciferase activity was measured 24 hours post-transfection according to manufacturer's protocol (Promega) using a Berthold Technologies Lumat LB9507 luminometer. Firefly luciferase values were normalized to Renilla luciferase values.

Pulse-chase

Cells were subjected to pulse-chase analysis as previously described [31]. The radioactive signal was enhanced by Autofluor (National Diagnostics). The dried polyacrylamide gel was exposed to film for up to one week at -80°C. Bands were quantified using GE Healthcare Typhoon Trio Variable Mode Imager.

Results

A UPR induces TRAM1

Cellular components involved in the extraction and destruction of ER substrates are upregulated during a UPR to assist in the disposal of misfolded ER proteins [2, 3]. Given that TRAM1 is involved in dislocation of an ER degradation substrate [29], is TRAM1 also upregulated during a UPR? To address this question, TRAM1 mRNA and proteins levels were examined from cells treated with or without tunicamycin, a drug that inhibits N-linked glycosylation and activates a UPR (Figure 1). The induction of a UPR was confirmed by the increase of BiP and CHOP mRNA levels (Figure 1A). TRAM1 mRNA was also significantly upregulated (∼4-fold), compared to that of the homologous ER polytopic membrane protein TRAM2 (53% amino acid identity) (Figure 1B). TRAM2 has been implicated in collagen biosynthesis, but the cytosolic tail of TRAM2 is required for this function, which shares only 15% identity with TRAM1 [39]. TRAM2 mRNA levels has also been shown to be regulated by bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP-2) and runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) in osteoblasts in a developmental stage-dependent manner, presumably due to the involvement of TRAM2 in type I collagen synthesis [40]. Consistent with the results of Figures 1A and 1B, protein levels of TRAM1 (Figure 1C and 1D, lane 1 vs. 2) and BiP (Figures 1C and 1D, lane 3 vs. 4) dramatically increased upon inclusion of tunicamycin (Figure 1C) and thapsigargin (Figure 1D). As a control, calnexin and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) levels were not elevated upon addition of tunicamycin or thapsigargin, demonstrating equivalent protein loading (Figures 1C and 1D, lanes 5-8). Here we show that TRAM1 is upregulated under conditions of ER stress.

Figure 1. A UPR induces TRAM1 expression.

(A, B) U373 cells treated with DMSO, 0.1μg/ml, or 0.5μg/ml tunicamycin (tm) for 18 hours were examined by qRT-PCR for (A) BiP, CHOP, (B) TRAM1, and TRAM2. Values are normalized to DMSO-treated cells, which is set to a fold change of 1. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance of p<0.05. (C, D) Total cell lysates of U373 treated with DMSO, (C) 0.1μg/ml tunicamycin, or (D) 200nM thapsigargin (tg) for 18 hours were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-TRAM1, anti-BiP, anti-calnexin, and anti-PDI antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated.

TRAM1 knockdown cells highly activate UPRE

ER stress upregulates factors designed to relieve stress, i.e. proteins involved in lipid biogenesis, protein folding, and protein degradation [2]. Conversely, the lack of a protein involved in stress relief will lead to elevated levels of stress; this can be measured by utilization of the unfolded protein response elements (UPRE), to which spliced XBP-1 and cleaved ATF6 bind [37, 41]. To measure the activation of a UPR, we utilized a construct encoding GFP under the control of UPRE (UPRE-gfp) [37]. Thapsigargin was used to induce a UPR due to its fast kinetics in eliciting ER stress. Cells transfected with UPRE-gfp were treated with or without thapsigargin and subjected to immunoblot (Figure 2A) and fluorescence (Figure 2B) analysis. A significant increase in GFP protein levels (Figure 2A, lanes 1-3) as well as fluorescence (Figure 2B) was observed upon treatment with merely 10nM thapsigargin. As a control for UPR activation, BiP protein levels increased with 10nM thapsigargin (Figure 2A, lanes 4-6) despite equivalent protein loading demonstrated by equal levels of PDI (Figure 2A, lanes 7-9). These results confirm that the UPRE-gfp reporter is sensitive to acute ER stress.

Figure 2. TRAM1 knockdown cells exhibit increased UPRE activation.

(A, B) 293T cells transfected with the UPRE-gfp construct were treated with DMSO, 10nM, or 100nM thapsigargin (tg) for 6 hours. (A) Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-GFP, anti-BiP and anti-PDI antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated. (B) Fluorescence values are normalized to DMSO-treated samples. (C, D) 293T cells co-transfected with the UPRE-gfp construct and either scrambled shRNA or shRNA to TRAM1 (shTRAM1-R2) were treated -/+ 10nM thapsigargin for 6 hours. (C) Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-GFP, anti-BiP, anti-TRAM1, anti-GAPDH, and anti-PDI antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated. (D) Fluorescence values are normalized to DMSO-treated cells transfected with scrambled shRNA. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance of p<0.05.

Next, activation of the UPRE-gfp reporter construct was examined in cells with limited TRAM1 expression. The induction of GFP levels was measured from cells transfected with scrambled shRNA or shRNA to TRAM1 (shTRAM1) (Supplemental Figure 1A) followed by treatment with or without thapsigargin by immunoblot analysis (Figure 2C) and fluorescence signal (Figure 2D). The inclusion of thapsigargin induced a robust increase in GFP expression (Figure 2C, lanes 1-2 and 2D) that was further enhanced in thapsigargin-treated shTRAM1 cells (Figure 2C, lanes 3-4 and 2D). Note, untreated cells transfected with shTRAM1 revealed a slight increase of GFP levels (Figure 2C). The increase in BiP levels was consistent with the GFP levels with regards to decreased levels of TRAM1 and thapsigargin-treatment (Figure 2C, lanes 5-8). An anti-TRAM1 immunoblot demonstrated decreased levels of TRAM1 (Figure 2C, lanes 9-12). Equivalent levels of protein were demonstrated by anti-GAPDH and anti-PDI immunoblots (Figure 2C, lanes 13-16 and 17-20). A consistent, yet less striking result was observed by GFP fluorescence analysis. Thapsigargin induced a ∼3-fold increase in GFP signal in scrambled shRNA cells while shTRAM1 cells revealed a ∼5-fold increase in UPRE promoter activation (Figure 2D). The difference in signal observed between fluorescence and immunoblot analyses is perhaps because fluorescence analysis measures GFP molecules capable of emitting energy whereas immunoblot analysis examines total protein levels. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the lack of TRAM1 limits misfolded protein export, thereby leading to hypersensitivity in UPRE activation.

To exclude the possibility that the elevated UPR in TRAM1 knockdown cells was due to defective protein import, we examined steady-state and newly synthesized levels of protein in cells that stably express shRNA to TRAM1 (U373shTRAM1-R2) or empty vector (U373vector) (Supplemental Figure 1B and [29]) treated with or without thapsigargin. No gross differences were observed from ER glycoproteins in U373vector and U373shTRAM1-R2 cells at steady state; in fact, there seem to be even more newly-synthesized glycoproteins in U373shTRAM1-R2 cells (Supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, decreasing TRAM1 expression does not have a major impact on ER protein import.

TRAM1 knockdown cells robustly induce NF-κB activity

Upon encountering ER stress, cells exhibit an increase in NF-κB activity dependent on eIF2α phosphorylation by PERK [42, 43]. Is NF-κB activity affected by decreasing TRAM1 expression? To address this question, a reporter construct containing an NF-κB promoter fused to luciferase gene was utilized. A construct encoding Renilla luciferase was used as a control for transfection efficiency. Cells transfected with constructs encoding Renilla luciferase and an NF-κB-driven firefly luciferase revealed transfection-induced stress by luciferase activity (Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B). To confirm these findings, the analysis of GFP expression using the UPRE-gfp reporter showed a slight increase in GFP levels upon transfection (Supplemental Figure 3C and 3D). Henceforth, luciferase values were normalized to cells transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter constructs, and not to untransfected cells. Cells transfected with the NF-κB reporter constructs demonstrated a ∼5-fold thapsigargin-mediated induction of NF-κB activity (Figure 3A), validating the sensitivity of NF-κB luciferase reporter construct to ER stress. We next examined luciferase activity from 293T cells transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter constructs and three different shRNA constructs to TRAM1 (shTRAM1-R1, shTRAM1-R2, and shTRAM1-R3) (Supplemental Figure 1A and [29]). Strikingly, cells expressing shTRAM1-R1, shTRAM1-R2, and shTRAM1-R3 revealed a ∼11-fold, ∼15-fold, and ∼ 8-fold increase in NF-κB activity compared to control cells (Figure 3B). To confirm these results in cells with more efficient knockdown of TRAM1, we examined U373 cells that stably express the three different shRNA constructs to TRAM1 (Supplemental Figure 1B and [29]). U373shTRAM1-R2 cells transfected with a NF-κB reporter construct demonstrated a ∼12-fold increase in NF-κB activity over U373vector cells, while a more modest ∼4.5-fold increase in luciferase activity was observed from U373shTRAM1-R1 and U373shTRAM1-R3 cells (Figure 3C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the decreased expression of TRAM1 resulted in an increased induction of NF-κB, and that levels of NF-κB activation correspond to the efficacy of TRAM1 knock-down [29].

Figure 3. NF-κB activity is enhanced in TRAM1 knockdown cells.

(A) 293T cells transfected with the NF-κB-luciferase reporter were treated -/+ 20nM thapsigargin (tg) for 6 hours and examined for luciferase activity. Values are normalized to DMSO-treated cells. (B) 293T cells co-transfected with the NF-κB-luciferase reporter and vector, shTRAM1-R1, shTRAM1-R2, and shTRAM1-R3 were assayed for luciferase activity. Values are normalized to vector-transfected cells. (C) U373vector, U373shTRAM1-R1, U373shTRAM1-R2, and U373shTRAM1-R3 cells transfected with the NF-κB-luciferase reporter were assayed for luciferase activity. Values are normalized to U373vector cells. (D) U373vector, U373shTRAM1-R1, U373shTRAM1-R2, and U373shTRAM1-R3 cells transfected with the NF-κB-luciferase reporter and increasing amounts of HA-TRAM1 cDNA as indicated were assayed for luciferase activity. Values depicted are normalized to U373vector cells transfected with 0μg TRAM1 cDNA. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance of p<0.05.

To verify that the lack of TRAM1 led to increased NF-κB activity, U373vector, U373shTRAM1-R1, U373shTRAM1-R2, and U373shTRAM1-R3 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of HA-TRAM1 cDNA along with the NF-κB reporter construct. In all cells, NF-κB activity decreased in a dose-responsive manner with increasing amounts of HA-TRAM1 cDNA (Figure 3D). Levels of HA-TRAM1 vary with respect to the efficacy of the shRNA construct expressed, but all cell lines showed increasing amounts of HA-TRAM1 recovered with increasing amounts of cDNA added (Supplemental Figure 1B, lanes 13-24). The complementation study demonstrates that low levels of TRAM1 resulted in high levels of constitutive NF-κB activation.

TRAM1 participates in the stability of ER membrane degradation substrates

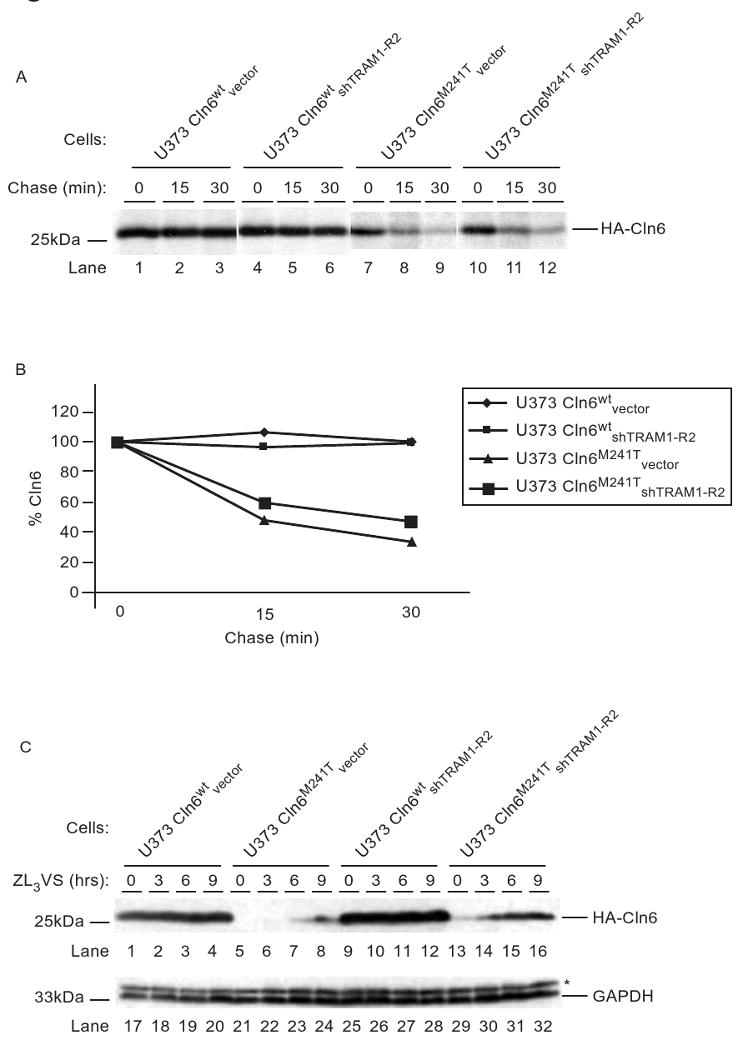

TRAM1 functions in HCMV US2- and US11-mediated dislocation of MHC class I heavy chains [29]. To further delineate the repertoire of ER degradation substrates dependent on TRAM1, we examined the stability of a mutant version of Cln6. Cln6 is a multipass ER membrane protein that lacks N-linked glycosylation sites; the point mutant Cln6M241T is associated with the lysosomal storage disease neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis [44] and is degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner [45]. U373 Cln6wtvector, U373 Cln6wtshTRAM1-R2, U373 Cln6M241Tvector, and U373 Cln6M241TshTRAM1-R2 cells treated with proteasome inhibitor were radiolabelled with [35S]-methionine and chased for 0, 15, and 30 minutes (Figure 4A). Cln6wt polypeptides were stable throughout the chase period regardless of the presence or absence of TRAM1 (Figure 4A, lanes 1-6). In contrast, Cln6M241T polypeptides were quickly degraded during the 30 minute chase period (Figure 4A, lanes 7-9). TRAM1 knockdown in these cells resulted in an increased stabilization of Cln6M241T polypeptides (∼20%) (Figure 4A, lanes 10-12), implying that TRAM1 participates in the degradation of Cln6M241T. The modest increase in Cln6M241T levels in TRAM1 knockdown cells is consistent with published data that TRAM1 acts as an efficient factor for the disposal of ER substrates.

Figure 4. ER-to-cytosol dislocation of Cln6M241T is TRAM1-dependent.

(A) U373 Cln6wtvector, U373 Cln6wtshTRAM1-R2, U373 Cln6M241Tvector and U373 Cln6M241TshTRAM1-R2 cells were subjected to a pulse-chase analysis in the presence of proteasome inhibitor (50μM ZL3VS, 1hr). Polypeptides were recovered with an anti-HA antibody and resolved via SDS-PAGE. (B) Levels of Cln6 proteins from (A) were quantified by phosphoimaging analysis and plotted as a percentage to the 0 min chase point (100%). (C) U373 Cln6wtvector, U373 Cln6M241Tvector, U373 Cln6wtshTRAM1-R2, and U373 Cln6M241TshTRAM1-R2 cells were subjected to proteasome inhibition (12.5μM ZL3VS) for up to 9 hours. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-HA and anti-GAPDH antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated.

To further demonstrate that TRAM1 plays a role in Cln6M241T degradation, levels of Cln6M241T were examined in TRAM1 knockdown cells under conditions that would decrease the dislocation rate of Cln6M241T. Hence, total cell lysates of U373 Cln6wtvector, U373 Cln6M241Tvector, U373 Cln6wtshTRAM1-R2, and U373 Cln6M241TshTRAM1-R2 cells treated with 12.5μM proteasome inhibitor (ZL3VS) for up to 9 hours were subjected to immunoblot analysis (Figure 4C). As expected, Cln6wt polypeptides were stable independent of proteasome inhibitor treatment or presence of TRAM1 (Figure 4C, lanes 1-4 and 9-12). In contrast, Cln6M241T polypeptides began to accumulate only after 6 hours of proteasome inhibitor treatment in control cells (Figure 4C, lanes 5-8). Strikingly, in TRAM1 knockdown cells, a minute amount of Cln6M241T was observed from untreated cells and significantly increased after 3 hours of ZL3VS treatment (Figure 4C, lanes 13-16). These results demonstrate that in the absence of TRAM1, Cln6M241T stability was increased, suggesting that TRAM1 plays a role in the disposal of Cln6M241T. An anti-GAPDH immunoblot revealed equivalent protein loading (Figure 5A, lanes 17-32). The data further emphasizes the role of TRAM1 for the degradation of ER substrates.

Figure 5. Stability of HCMV US2 polypeptide is TRAM1-dependent.

Total cell lysates from U373 US2vector, U373 US2shTRAM1-R1, U373 US2shTRAM1-R2, and U373 US2shTRAM1-R3 were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-US2, anti-TRAM1, anti-PDI, and anti-calnexin antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated.

To determine if TRAM1 is involved in the dislocation of another type I ER membrane protein, levels of HCMV US2 were examined in the presence or absence of TRAM1. HCMV US2 induces the degradation of class I heavy chains, but is also targeted for proteasomal destruction [15]. Levels of US2 polypeptide were examined from U373 US2vector, U373 US2shTRAM1-R1, U373 US2shTRAM1-R2, and US2shTRAM1-R3 cells by immunoblot analysis (Figure 5). The most efficient knockdown of TRAM1 was observed from U373 US2shTRAM1-R2 cells, albeit U373 US2shTRAM1-R3 cells knocked down TRAM1 by at least 75% (Figure 5, lanes 5-8, and [29]). Examination of US2 levels in TRAM1 knockdown cells revealed that US2 polypeptides accumulate most abundantly in U373 US2shTRAM1-R2 cells (Figure 5, lanes 1-4). Equivalent levels of protein across lanes are demonstrated by anti-PDI and anti-calnexin immunoblots (Figure 5, lanes 9-12 and 13-16). The accumulation of class I heavy chains in TRAM1 knockdown cells was confirmed under these conditions (Supplemental Figure 4). The sharp increase of US2 molecules in TRAM1 knockdown cells further validates that TRAM1 provides efficiency in the disposal of ER proteins. Collectively, the data demonstrates that TRAM1 is important for a variety of ER-resident membrane proteins targeted for degradation.

TRAM1 does not participate in degradation of soluble substrates

Does TRAM1 participate in the degradation of soluble ER degradation substrates? To address this question, the stability of the canonical soluble ER degradation substrate α1-antitrypsin nullHK (α1ATNHK) [27] was examined in cells lacking TRAM1. Total cell lysates culled from U373 α1ATNHKvector and U373 α1ATNHKshTRAM1 cells treated with or without proteasome inhibitor were examined by immunoblot analysis (Figure 6A). As expected, levels of α1ATNHK increased upon inclusion of proteasome inhibitor (Figure 6A, lanes 1-2). In the absence of TRAM1, there was no major difference in the amounts of α1ATNHK that accumulated upon treatment with proteasome inhibitor (Figure 6A, lanes 3-4). In addition, cells lacking TRAM1 resulted in a slight decrease in levels of faster-migrating degradation intermediates (Figure 6A, lane 2 vs. 4). These results imply that TRAM1 does not play a significant role in the ER-to-cytosol dislocation of α1ATNHK. An anti-PDI immunoblot demonstrates equivalent levels of protein across lanes (Figure 6A, lanes 9-12). Interestingly, analysis of proteasome function by examining the accumulation of ubiquitinylated species reveal an increased level of polyubiquitinylated species in the absence of TRAM1 (Figure 6A, lanes 6 vs. 8) suggesting that the destruction of these substrates was limited in the absence of TRAM1. These higher-molecular weight species are likely derived from ER degradation substrates. Collectively, the data implies that TRAM1 is involved in the selective destruction of ER substrates.

Figure 6. Stability of soluble ER and cytosolic degradation substrates are TRAM1-independent.

(A) Total cell lysates culled from U373 α1ATNHKvector and U373 α1ATNHKshTRAM1-R2 cells treated with or without proteasome inhibitor (2.5μM ZL3VS) for 12 hours were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-α1antitrypsin, anti-ubiquitin, and anti-PDI antibodies. (B) 293T cells transfected with Ub-M-GFP or Ub-R-GFP and scrambled shRNA or shRNA to TRAM1 were treated with or without proteasome inhibitor (2.5μM ZL3VS) for 12 hours. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analyses using anti-GFP and anti-GAPDH antibodies. The respective proteins and relative molecular weight markers are indicated.

To verify that TRAM1 function is exclusive for ER degradation substrates, we examined the stability of a cytosolic N-end rule degradation substrate [46] in the absence of TRAM1 (Figure 6B). An N-end rule substrate is degraded in a ubiquitin/proteasome dependent manner when the amino-terminus of the polypeptide is a de-stabilizing amino acid (e.g. R or K). Taking advantage of the promiscuous nature of ubiquitin isopeptidase, we utilized chimeric constructs encoding ubiquitin followed by GFP in which the N-terminus of GFP is either methionine (M) (Ub-M-GFP) or arginine ® (Ub-R-GFP) [47] after cleavage of ubiquitin. Cells were transfected with either Ub-M-GFP or Ub-R-GFP and scrambled shRNA or shRNA against TRAM1, then untreated or treated with proteasome inhibitor. Total cell lysates were examined for GFP stability using immunoblot analysis (Figure 6B). Ub-M-GFP, as expected, was stable regardless of proteasome inhibition or presence of TRAM1 (Figure 6B, lanes 1-4). In contrast, Ub-R-GFP was only observed from cells treated with proteasome inhibitor, confirming that it is degraded in a proteasome dependent manner (Figure 6B, lanes 5-6). Consistent with the hypothesis that TRAM1 only affects the degradation of ER proteins, the stability of Ub-R-GFP was independent of TRAM1 (Figure 6B, lanes 7-8). The anti-GAPDH immunoblot was indicative of equivalent protein loading (Figure 6B, lanes 9-16). Together, these findings substantiate the model that TRAM1 plays a role in the dislocation of ER membrane proteins.

Discussion

ER stress is encountered when an excess of polypeptides are unable to achieve their native state [1]. These polypeptides must be targeted for degradation by factors that mediate the disposal of such substrates to maintain cell viability; accordingly, one of the consequences of a UPR is the upregulation of such disposal factors [2, 3]. Consistent with this model was the upregulation of TRAM1 upon induction of a UPR (Figure 1). In fact, the UPR was intensified in TRAM1 knockdown cells (Figure 2), further confirming the relationship between TRAM1 and ER stress. Although initially characterized in polypeptide translocation, TRAM1 may function in other areas of protein processing. TRAP sets a precedence for proteins characterized in processing of nascent polypeptides found to be involved in both ERAD and the UPR [27]. Examining a variety of ERAD substrates to establish the boundaries for the set of proteins dependent upon TRAM1 for ER-to-cytosol dislocation, we found that membrane-bound ER proteins are TRAM1-dependent regardless of glycosylation status (Figures 4 and 5), but that soluble luminal proteins appear to be TRAM1-independent (Figure 6). Since the lack of TRAM1 induced the accumulation of membrane-bound ER-resident degradation substrates, TRAM1 likely functions in the efficient removal of ER proteins destined for destruction. TRAM1 contacts hydrophobic patches such as transmembrane domains and signal sequences of nascent polypeptides [28]. Its ability to mediate lateral insertion of nascent polypeptides into the membrane bilayer may also be called upon to mediate extraction of polypeptides destined for proteasomal degradation. TRAM1 may provide the ‘grease’ to ease polypeptides in and out of the ER. Therefore, in cells lacking TRAM1, polypeptides have a harder time getting out of the ER, and thus the accumulation of aberrant ER proteins probably triggers a more robust induction of the UPR in TRAM1 knockdown cells. The current study solidifies the role of TRAM1 in the dislocation of a selective group of ERAD substrates, as well as the effects of a dearth of TRAM1: namely, an accumulation of ER-resident polypeptides that lead to a UPR.

Perturbations of the ER, whether by expression of ER-resident polypeptides, drugs that interfere with protein folding, or viral agents, have been shown to activate NF-κB [48]. Upon encountering ER stress, cells exhibit an increase in eIF2α-dependent NF-κB activity [42, 43], presumably to promote pro-survival signals by inhibiting the expression of the pro-apoptotic molecule CHOP [49]. The lack of TRAM1 caused elevated NF-κB levels that were reducible by TRAM1 cDNA complementation (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 1B), implying that these cells were in a pro-survival mode in response to an aggregation of misfolded ER proteins. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating NF-κB activation due to the loss of an ER protein. Together, the data indicates that the lack of physiological levels of TRAM1 results in potentiated cellular stress signals.

Conclusions

TRAM1 is selectively upregulated upon induction of a UPR to facilitate dislocation of proteins and likely reduces the amount of misfolded proteins that accumulate in the ER. TRAM1 is important in the dislocation of ERAD substrates that are membrane-bound. TRAM1 knockdown cells demonstrate a potentiated UPR upon an acute ER stress, probably because cells lacking TRAM1 have a more difficult time in disposal of misfolded polypeptides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant AI060905 and the Irma T. Hirschl Trust.

Abbreviations

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- Cln6

ceroid-lipofuscinosis neuronal protein 6

- eIF2α

alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TRAM1

translocating chain-associated membrane protein 1

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPRE

unfolded protein response elements

- XBP-1

X-box binding protein 1

- ZL3VS

carboxybenzyl-leucyl-leucyl-leucine vinyl sulfone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Caroline L. Ng, Email: caroline.ng@mssm.edu.

Kristina Oresic, Email: kristina.oresic@mssm.edu.

Domenico Tortorella, Email: domenico.tortorella@mssm.edu.

References

- 1.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng DT, Spear ED, Walter P. The unfolded protein response regulates multiple aspects of secretory and membrane protein biogenesis and endoplasmic reticulum quality control. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:77–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Vallabhajosyula P, Otipoby KL, Rajewsky K, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–9. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:525–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Choudhury P, Cabral CM, Sifers RN. Oligosaccharide modification in the early secretory pathway directs the selection of a misfolded glycoprotein for degradation by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5861–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward CL, Kopito RR. Intracellular turnover of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Inefficient processing and rapid degradation of wild-type and mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su HL, Liao CL, Lin YL. Japanese encephalitis virus infection initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress and an unfolded protein response. J Virol. 2002;76:4162–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4162-4171.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu CY, Hsu YW, Liao CL, Lin YL. Flavivirus infection activates the XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response to cope with endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Virol. 2006;80:11868–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00879-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romisch K. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:435–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004;429:841–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lilley BN, Ploegh HL. A membrane protein required for dislocation of misfolded proteins from the ER. Nature. 2004;429:834–40. doi: 10.1038/nature02592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lilley BN, Ploegh HL. Multiprotein complexes that link dislocation, ubiquitination, and extraction of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schekman R. Cell biology: a channel for protein waste. Nature. 2004;429:817–8. doi: 10.1038/429817a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiertz EJ, Tortorella D, Bogyo M, Yu J, Mothes W, Jones TR, Rapoport TA, Ploegh HL. Sec61-mediated transfer of a membrane protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome for destruction. Nature. 1996;384:432–8. doi: 10.1038/384432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raasi S, Wolf DH. Ubiquitin receptors and ERAD: a network of pathways to the proteasome. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biederer T, Volkwein C, Sommer T. Degradation of subunits of the Sec61p complex, an integral component of the ER membrane, by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Embo J. 1996;15:2069–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiller MM, Finger A, Schweiger M, Wolf DH. ER degradation of a misfolded luminal protein by the cytosolic ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Science. 1996;273:1725–8. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikkert M, Doolman R, Dai M, Avner R, Hassink G, van Voorden S, Thanedar S, Roitelman J, Chau V, Wiertz E. Human HRD1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in degradation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3525–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morito D, Hirao K, Oda Y, Hosokawa N, Tokunaga F, Cyr DM, Tanaka K, Iwai K, Nagata K. Gp78 cooperates with RMA1 in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of CFTRDeltaF508. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1328–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song BL, Sever N, DeBose-Boyd RA. Gp78, a membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase, associates with Insig-1 and couples sterol-regulated ubiquitination to degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Mol Cell. 2005;19:829–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Q, Li L, Ye Y. Regulation of retrotranslocation by p97-associated deubiquitinating enzyme ataxin-3. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:963–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassink GC, Zhao B, Sompallae R, Altun M, Gastaldello S, Zinin NV, Masucci MG, Lindsten K. The ER-resident ubiquitin-specific protease 19 participates in the UPR and rescues ERAD substrates. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:755–61. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst R, Mueller B, Ploegh HL, Schlieker C. The otubain YOD1 is a deubiquitinating enzyme that associates with p97 to facilitate protein dislocation from the ER. Mol Cell. 2009;36:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boisrame A, Beckerich JM, Gaillardin C. A mutation in the secretion pathway of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica that displays synthetic lethality in combination with a mutation affecting the signal recognition particle. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:601–9. doi: 10.1007/s004380050002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menetret JF, Hegde RS, Heinrich SU, Chandramouli P, Ludtke SJ, Rapoport TA, Akey CW. Architecture of the ribosome-channel complex derived from native membranes. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:445–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagasawa K, Higashi T, Hosokawa N, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K. Simultaneous induction of the four subunits of the TRAP complex by ER stress accelerates ER degradation. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:483–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapoport TA, Goder V, Heinrich SU, Matlack KE. Membrane-protein integration and the role of the translocation channel. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:568–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oresic K, Ng CL, Tortorella D. TRAM1 Participates in Human Cytomegalovirus US2- and US11-mediated Dislocation of an Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane Glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5905–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807568200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noriega VM, Tortorella D. A bipartite trigger for dislocation directs the proteasomal degradation of an endoplasmic reticulum membrane glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4031–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706283200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oresic K, Noriega V, Andrews L, Tortorella D. A structural determinant of human cytomegalovirus US2 dictates the down-regulation of class I major histocompatibility molecules. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19395–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker BM, Tortorella D. Dislocation of an endoplasmic reticulum membrane glycoprotein involves the formation of partially dislocated ubiquitinated polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26845–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hochstenbach F, David V, Watkins S, Brenner MB. Endoplasmic reticulum resident protein of 90 kilodaltons associates with the T- and B-cell antigen receptors and major histocompatibility complex antigens during their assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4734–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson IA, Niman HL, Houghten RA, Cherenson AR, Connolly ML, Lerner RA. The structure of an antigenic determinant in a protein. Cell. 1984;37:767–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuen T, Zhang W, Ebersole BJ, Sealfon SC. Monitoring G-protein-coupled receptor signaling with DNA microarrays and real-time polymerase chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:556–69. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen J, Prywes R. ER stress signaling by regulated proteolysis of ATF6. Methods. 2005;35:382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto K, Yoshida H, Kokame K, Kaufman RJ, Mori K. Differential contributions of ATF6 and XBP1 to the activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-responsive cis-acting elements ERSE, UPRE and ERSE-II. J Biochem. 2004;136:343–50. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita T, Nolan GP, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Independent modes of transcriptional activation by the p50 and p65 subunits of NF-kappa B. Genes Dev. 1992;6:775–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stefanovic B, Stefanovic L, Schnabl B, Bataller R, Brenner DA. TRAM2 protein interacts with endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump Serca2b and is necessary for collagen type I synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1758–68. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1758-1768.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pregizer S, Barski A, Gersbach CA, Garcia AJ, Frenkel B. Identification of novel Runx2 targets in osteoblasts: cell type-specific BMP-dependent regulation of Tram2. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:1458–71. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Shen J, Arenzana N, Tirasophon W, Kaufman RJ, Prywes R. Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27013–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang HY, Wek SA, McGrath BC, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Cavener DR, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is required for activation of NF-kappaB in response to diverse cellular stresses. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5651–63. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5651-5663.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng J, Lu PD, Zhang Y, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Sonenberg N, Harding HP, Ron D. Translational repression mediates activation of nuclear factor kappa B by phosphorylated translation initiation factor 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10161–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10161-10168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kyttala A, Lahtinen U, Braulke T, Hofmann SL. Functional biology of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL) proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:920–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oresic K, Mueller B, Tortorella D. Cln6 mutants associated with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis are degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner. Biosci Rep. 2009;29:173–81. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule: functions, mysteries, uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12142–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dantuma NP, Lindsten K, Glas R, Jellne M, Masucci MG. Short-lived green fluorescent proteins for quantifying ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis in living cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:538–43. doi: 10.1038/75406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA. The ER-overload response: activation of NF-kappa B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:63–7. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schapansky J, Olson K, Van Der Ploeg R, Glazner G. NF-kappaB activated by ER calcium release inhibits Abeta-mediated expression of CHOP protein: enhancement by AD-linked mutant presenilin 1. Exp Neurol. 2007;208:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.